Emergency (1975-77): India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be acknowledged in your name. |

Contents |

In brief

India Today, December 29, 2008

Gunjeet K. Sra

The Emergency, June 1975-March 1977: It effectively bestowed on Indira Gandhi the power to rule by decree, suspending elections as well as civil liberties, such as the right to free press.

Highlights

The Times of India, Jun 21 2015

Patrick Clibbens

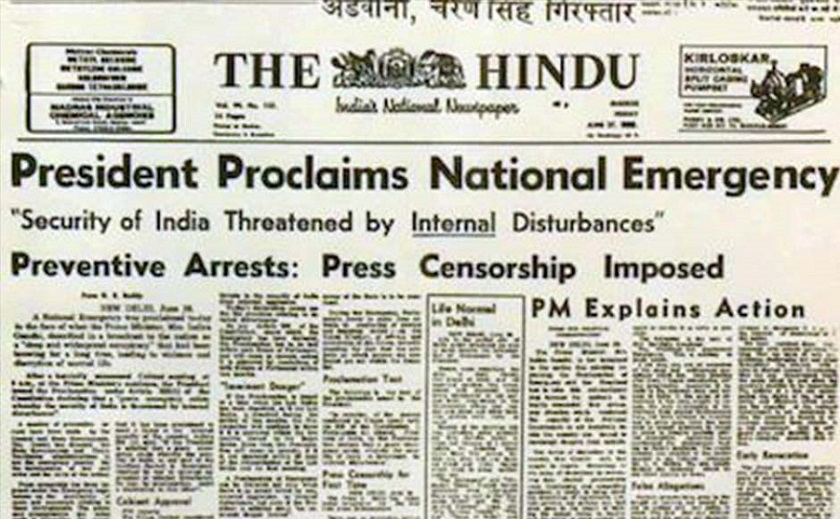

Emergency wasn't just about Sanjay and his playground

Forty years, on the night of June 25, 1975, President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared that India was in a state of `grave emergency'. Although the government had declared emergencies twice before (indeed the 1971 emergency was still in place), they had been in times of war.

In 1975, the government was targeting events within India itself -the `internal disturbance' that it claimed threatened the security of India.

The government's crackdown transformed Indian political life. Yet for many people today , the Emergency is best remembered for its twin social programmes of urban clearances and mass sterilizations.The government pursued them on a massive scale. Almost 11,000,000 people were sterilized in just two years, while 700,000 had their homes or businesses demolished in Delhi alone.

When describing the Emergency , historians have relied on one document more than any other: the three-volume Shah Commission report published in 1978. Justice J C Shah oversaw a fact-finding team which gathered thousands of documents and testimonies. For years the report was hard to trace, with copies languishing in a few uni versity libraries, but since its republication by Era Sezhiyan this crucial document is readily available in India. It is the source of much of our knowledge about the Emergency , but its own blind spots and unspoken assumptions are the origin of many common misconceptions today .

When the Shah Commission was appointed in May 1977, the new Janata government instructed it to inquire into the `excesses' committed during the Emergency -this terminology implied that the Emergency consisted of good policies pursued with too much zeal.The report also assumes a `drastic change after the Emergency', and the idea that it was a short-term aberration was built into the Commission's inquiries. More extensive historical research shows that, at least for the highly emotive social programmes, we must qualify this view.

In the Emergency family planning programme, New Delhi set targets cascading from the central departments out through states to the most junior local officials. The programme created tissues of targets, incentives and disincentives disproportionately directed at the poor and those reliant on government jobs, housing or welfare. All these features predated the Emergency . For example, since 1959 the State of Madras (now Tamil Nadu) had given `canvassers' a cash payment for each man they brought to be sterilized, though they knew the canvassers often misled patients. Mahar ashtra had used a package of `disincentives' to pressure people since 1967, while Kerala had pio neered `massive vasectomy camps' which sterilized thousands at a time in the early 1970s.

Another feature of the Shah Commission's re port which has often figured in discussions of the Emergency is its focus on a few personalities, par ticularly Indira Gandhi's younger son, Sanjay .

Justice Shah naturally wanted to pin down those responsible for the abuses he had documented and it is clear that Sanjay liked to issue instructions to ministers despite having no government position of any kind. Yet identifying Emergency policies so closely with one man means we risk losing sight of other actors.

In particular, regarding Sanjay as the `evil genius' of the whole demolition programme has focused all the attention on Delhi and its environs, as this was Sanjay's playground. Justice Shah dedicated 63 pages to demolitions in Delhi, but covered the rest of the country in 10 pages without providing any statistics. Some large states were neglected entirely . More recently , the influential account by Indira Gandhi's secretary P N Dhar also states that demolitions took place in Delhi, Haryana and western UP `in order to please Sanjay Gandhi'. UP `in order to please Sanjay Gandhi'.

Yet if we take just one example -Mumbai -we can see that this focus is misleading. During the Emergency , the city finally succeeded in demolishing the dwellings of over 70,000 people from the Janata Colony and transported them to the deso late, marshy land at the tip of Trombay . Beggars were also a target: thousands were rounded up and transported to a holding camp in a cattle shed and then to `work camps' 160km inland, where they were also sterilized.

In this anniversary year, we will no doubt hear more about the high politics and drama of the Emergency . Yet there is so much we still don't know about the many different ways in which people across India experienced the Emergency in their everyday lives. The Shah Commission has served us well, but it's time to get researching.

Emergency: The Dark Age of Indian democracy

The Hindu, June 27, 2015

From June 25, 1975 to March 21, 1977 were 21 months of uncertainty and fear triggered by the imposition of internal Emergency by the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. On the occasion of this period's 40th anniversary, here is a look at the mood in the country as democracy went under.

What

The Emergency was set in motion by the Indira Gandhi government on June 25, 1975 and was in place for 21 months till its withdrawal on March 21, 1977. The order gave Ms. Gandhi the authority to rule by decree wherein civil liberties were curbed. An external Emergency was already in place even before the imposition of the internal one.

How

The Emergency was officially issued by the then President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed. With the suspension of the Fundamental rights, politicians who opposed Ms. Gandhi were arrested. Threat to national security and bad economic conditions were cited as reasons for the declaration. In Tamil Nadu, the Karunanidhi government was dissolved. The DMK leader’s son M.K. Stalin was arrested amidst protests under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act.

Chennai’s newspapers go blank

Writer Gnani, who was the working as a reporter in a newspaper in Chennai, recalls how the city reacted. “Among the politically aware, there was confusion as to what will happen... “The Censor wanted to kill newspapers by delaying approvals. Along with letting pages go blank, sometimes innocuous stuff like how to make onion raitha (salad) would be printed since political news could not be taken,” he says.

Calcutta’s prophets of doom

“I was in Calcutta for my Rajya Sabha election, scheduled for 26 June,” writes President Pranab Mukherjee in his book The Dramatic Decade: The Indira Years. “I got to the assembly building at about 9.30 a.m. It was teeming with state legislators, ministers and political leaders, some with questions and others with conspiracy theories. Some went to the extent of suggesting that, a la Mujibur Rahman of Bangladesh, Indira Gandhi had abrogated the Constitution and usurped power for herself, with the army in tow. I corrected these prophets of doom, saying that the Emergency had been declared according to the provisions of the Constitution rather than in spite of it.”

Gun shots in Delhi

There was nothing wild or exaggerated, however, about what the bush telegraph said concerning the police firing at Delhi's Turkman Gate where slums were demolished and those living in them "relocated". Soon thereafter, gunfire was heard also at Muzaffarnagar, a town in Uttar Pradesh, 100 km away from the national capital. Above all, forced vasectomies, in pursuance of one of the five points in Sanjay's personal agenda, were to spread both fear and revulsion across North India.

Arrests in Bangalore

Several senior BJP leaders now, including the former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and LK Advani and socialist leaders such as Shyam Nandan Mishra and Madhu Dandavate, were arrested in Bangalore on June 26... With so many leading figures in the same jail, Bangalore became an important point in the movement to oppose Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

Unlearnt lessons of the Emergency - Subramanian Swamy

When attempts at seeking homogeneity of Indian society are carried beyond a point, it is dangerous for democracy... Those of us who can stand up, must do so now.

Mastering the drill of democracy - Gopalkrishna Gandhi

The Emergency is a distant memory today because the nation’s collective spine did not bend, the media stayed unbent and the judiciary remained independent.

"An avoidable event"

Pranab Mukherjee, December 12, 2014

The 1975 Emergency was perhaps an “avoidable event” and Congress and Indira Gandhi had to pay a heavy price for this “misadventure” as suspension of fundamental rights and political activity, large scale arrests and press censorship adversely affected people, says President Pranab Mukherjee.

A junior minister under Gandhi in those turbulent times, Mukherjee however, is also unsparing of the opposition then under the leadership of the late Jayaprakash Narayan, JP , whose movement appeared to him to be “directionless”. The President has penned his thoughts about the tumultuous period in India's post-independence history in his book “The Dramatic Decade: the Indira Gandhi Years” that has just been released.

He discloses that Indira Gandhi was not aware of the Constitutional provisions allowing for declaration of Emergency that was imposed in 1975 and it was Siddartha Shankar Ray who led her into the decision.

Ironically, it was Ray, then Chief Minister of West Bengal, who also took a sharp aboutturn on the authorship of the Emergency before the Shah Commission that went into `excesses' during that period and disowned that decision, according to Mukherjee.

Mukherjee, who celebrated his 79th birthday on Thursday, says,“The Dramatic Decade is the first of a trilogy; this book covers the period between 1969 and 1980...I intent to deal with the period between 1980 and 1998 in volume II, and the period between 1998 and 2012, which marked the end of my active political career, in volume III.“

“At this point in the book, it will be sufficient to say here that many of us who were part of the Union Cabinet at that time (I was a junior minister) did not then understand its deep and far reaching impact.“

Mukherjee's 321-page book covers various chapters including the liberation of Bangladesh, JP's offensive, the defeat in the 1977 elections, split in Congress and return to power in 1980 and after.

Why Indira Gandhi imposed the Emergency

Adrija Roychowdhury , June 25, 2018: The Indian Express

“The President has proclaimed Emergency. There is nothing to panic about.” The words of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi blared from the All India Radio in the wee hours of June 26. The nation, on the receiving end of this piece of news, was as unsuspecting of it as were Gandhi’s Cabinet ministers who had been informed just hours before the PM proceeded to the AIR studio. The proclamation of Emergency had been signed by President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed the previous night itself. Soon after, newspaper presses across Delhi sank into darkness as a power cut ensured that nothing could be printed for the next two days. In the early hours of June 26, on the other hand, hundreds of political leaders, activists, and trade unionists opposed to the Congress Party were imprisoned.

The goal of the 21-month-long Emergency in the country was to control “internal disturbance”, for which the constitutional rights were suspended and freedom of speech and the press withdrawn. Indira Gandhi justified the drastic measure in terms of national interest, primarily based on three grounds. First, she said India’s security and democracy was in danger owing to the movement launched by Jayaprakash Narayan. Second, she was of the opinion that there was a need for rapid economic development and upliftment of the underprivileged. Third, she warned against the intervention of powers from abroad which could destabilise and weaken India.

The months preceding the declaration of the Emergency were fraught with economic troubles — growing unemployment, rampant inflation and scarcity of food. The dismal condition of the Indian economy was accompanied by widespread riots and protests in several parts of the country. Interestingly, the hitherto simmering borders of the country were rather quiet in the years preceding the Emergency. “As if to compensate, there was now trouble in the heartland, in parts of the country which, for reasons of history, politics, tradition, and language, had long considered themselves integral parts of the Republic of India,” writes historian Ramachandra Guha in his book, ‘India after Gandhi.’ The trouble began in Gujarat, spread to Bihar and from there to several other parts of Northern India. While the streets were raging against Gandhi’s governance, another challenge came to the doorstep of the prime minister in the form of a petition filed in the Allahabad High Court.

Here are the four major occurrences of the 1970s following which Indira Gandhi declared the Emergency.

Navnirman Andolan in Gujarat

In December 1973, students of L D College of Engineering in Ahmedabad went on a strike to protest against a hike in school fees. A month later, students of Gujarat University erupted in protest, demanding the dismissal of the state government. It called itself the ‘Navnirman movement’ or the movement for regeneration. Gujarat at this point in time was governed by the Congress under chief minister Chimanbhai Patel. The government was notorious for its corruption, and its head popularly referred to as chiman chor (thief).

The student protests against the government escalated and soon factory workers and people from other sectors of society joined in. Clashes with the police, burning of buses and government office and attacks on ration shops became an everyday occurrence. By February 1974, the central government was forced to act upon the protest. It suspended the Assembly and imposed President’s rule upon the state. “The last act of the Gujarat drama was played in March 1975 when, faced with continuing agitation and fast unto death by Morarji Desai, Indira Gandhi dissolved the assembly and announced fresh elections to it in June,” writes historian Bipin Chandra in his book, ‘India since Independence.’

The JP movement

Following in the footsteps of Gujarat or rather inspired by its success, a similar movement was launched in Bihar. A student protest erupted in Bihar in March 1974 to which opposition forces lent their strength. First, it was soon headed by 71-year-old freedom fighter Jayaprakash Narayan, popularly called JP. Second, in the case of Bihar, Indira Gandhi did not concede to the suspension of the Assembly. However, the JP movement was significant in determining her to declare Emergency.

A hero of the freedom struggle, JP had been known for his selfless activism since the days of the nationalist movement. “His entry gave the struggle a great boost, and also changed its name; what was till then the ‘Bihar movement’ now became the ‘JP movement’,” writes Guha. He motivated students to boycott classes and work towards raising the collective consciousness of the society. There were a large number of clashes with the police, courts, and offices, schools and colleges were being shut down.

In June 1974, JP led a large procession through the streets of Patna which culminated in a call for ‘total revolution’. He urged the dissenters to put pressure on the existing legislators to resign, so as to be able to pull down the Congress government. Further, JP toured across large sections of North India, drawing students, traders and sections of the intelligentsia towards his movement. Opposition parties who were crushed in 1971, saw in JP a popular leader best suited to stand up against Gandhi. JP too realised the necessity of the organisational capacity of these parties in order to be able to face Gandhi effectively. Gandhi denounced the JP movement as being extra-parliamentary and challenged him to face her in the general elections of March 1976. While JP accepted the challenge and formed the National Coordination Committee for the purpose, Gandhi soon imposed the Emergency.

The railways’ protest

Even as Bihar was burning in agitations, the country was paralysed by a railways strike led by socialist leader George Fernandes. Lasting for three weeks, in May 1974, the strike resulted in the halt of the movement of goods and people. Guha, in his book, notes that as many as a million railwaymen participated in the movement. “There were militant demonstrations in many towns and cities- in several places, the army was called out to maintain the peace,” he writes. Gandhi’s government came down heavily on the protesters. Thousands of employees were arrested and their families were driven out of their quarters.

The Raj Narain verdict

While opposition parties, trade unions, students and parts of the intelligentsia had occupied the streets in protest against Indira Gandhi’s government, a new threat emerged before her in the form of a petition filed in the Allahabad High Court by socialist leader Raj Narain who had lost out to Gandhi in Raebareli parliamentary elections of 1971. The petition accused the prime minister of having won the elections through corrupt practices. It alleged that she spent more money than was allowed and further that her campaign was carried out by government officials.

On March 19, 1975, Gandhi became the first Indian prime minister to testify in court. On June 12, 1975, Justice Sinha read out the judgment in the Allahabad High Court declaring Gandhi’s election to Parliament as null and void, but she was given a span of 20 days to appeal to the Supreme Court.

On June 24, the Supreme Court put a conditional stay on the High Court order: Gandhi could attend Parliament, but would not be allowed to vote unless the court pronounced on her appeal. The judgments gave the impetus to the JP movement, convincing them of their demand for the resignation of the prime minister. Further, by now even senior members of the Congress party were of the opinion that her resignation would be favourable to the party. However, Gandhi firmly held on to the prime ministerial position with the conviction that she alone could lead the country in the state that it was in.

A day after the Supreme Court judgment, an ordinance was drafted declaring a state of internal emergency and the President signed on it immediately. In her letter to the President requesting the declaration of Emergency, Gandhi wrote, “Information has reached us that indicate imminent danger to the security of India.” In an interview with journalist Jonathan Dimbleby in 1978, when Gandhi was asked the precise nature of the danger to Indian security that drove her to declare a state of emergency, she promptly replied, “it was obvious, isn’t it? The whole subcontinent had been destabilised.”

The Diaspora

Himanshi Dhawan, June 29, 2025: The Times of India

From: Himanshi Dhawan, June 29, 2025: The Times of India

From: Himanshi Dhawan, June 29, 2025: The Times of India

In Sept 1975, just six months after Anand Kumar arrived at the University of Chicago, his scholarship was abruptly withheld due to “adverse reports”. Kumar, then president of JNU Students’ Union, had gone to the US to pursue a doctorate in sociology. But instead of focusing solely on academics, he had been travelling across American university campuses, delivering fiery speeches demanding the release of JP (as the socialist leader Jayaprakash Narayan was known) and calling for the immediate withdrawal of the Emergency in India. Instead, his scholarship was withdrawn. “I was surprised. I didn’t think the govt would go this far,” Kumar recalls.

To rein in activists like Kumar, the long arm of the state had reached overseas. Kumar, who is Dayanand Bandodkar Chair professor at Goa University, says, “Political silence was not part of the contract I had signed when I was given the scholarship.”

Midnight swoops by the police, men being bundled off for forcible sterilisations, blank editorials in newspapers, these and many more stories define our memories of the Emergency that completed 50 years on June 25. But the struggles of overseas Indians — though much smaller in number — were no less significant. Over the course of two years — between June 1975 to March 1977 — students and professionals in the US found ways to create moral pressure on Indira Gandhi. Some of them travelled to campuses to raise awareness like Kumar, while others took out advertisements to shame India internationally, ambushed travelling ministers and even embarked on a ‘Satyagraha Walk’ from Philadelphia to New York. London-based Friends of India Society International (FISI) that was backed by the R S S and headed by Harvard economist Subramanian Swamy ran a similar campaign but that was focused on freeing JP. Swamy, an MP at the time, had evaded arrest and escaped from India to run the campaign from overseas.

A SOLID FRONT

In his recent book ‘The Conscience Network: A Chronicle of Resistance to a Dictatorship’, author Sugata Srinivasaraju writes about how “pacifists, Quakers, civil rights activists, academics, authors, senators and Congressmen in the United States came together in solidarity to form a network of conscience to save India’s democracy.”

“Eventually,” Kumar says, “there were half a dozen people who were willing to stick their neck out.” A motley group of students and professionals started Indians For Democracy (IFD), which included Kumar, another PhD student Ravi Chopra, engineer S R Hiremath who was working as an operations research professional, his wife Mavis Sigwalt and businessman Shrikumar Poddar. “People had gone to the US to pursue a career not to chase a revolution. But JP’s name as a social reformer had a charm,” Kumar says.

The pushback was inevitable. In a report from March 1976, The New York Times quoted the then Indian ambassador to the US T N Kaul, describing IFD as a “very small group” that had “joined hands with all kinds of subversive elements. They are only degrading themselves by washing dirty linen in public.”

SWAYING OPINIONS

One of the most significant challenges was to break the narrative that the Indian govt was working within the ambit of the Constitution to maintain law and order in the country. The “very small group” though punched way above its weight. Kumar says, “The US at the time was home to so many protests that it was hard to break through the clutter. We decided to issue advertisements in newspapers to grab attention.”

An advertisement issued on Aug 15, 1975 on India’s Independence Day in the New York Times read, “Don’t let the light go out on Indian democracy.” The Free JP Campaign in London created a campaign called ‘Mahatma in Exile’ (equating JP to Gandhi) and ran it for months, starting October 2, 1975.

Kumar recalls editing newsletters like Swaraj and Indian Opinion that printed handwritten, cyclostyled reports of excesses committed by the administration smuggled from India. IFD also circulated a report on human rights violations in India and the treatment meted out to prisoners that received a lot of attention in the western press. Another major breakthrough was convincing international human rights organisation Amnesty International to describe the political prisoners as “prisoners of conscience.”

INSPIRED BY MAHATMA

The Mahatma was a huge inspiration not just for the protestors but also the most recognisable name for the western audience. On the first anniversary of the Emergency, which lasted for 21 months, more than a hundred IFD protestors went on a day’s fast. They created a mock jail, in which they had placed an effigy of Gandhi, suggesting that he, too, would have been in jail had he been alive during the Emergency, writes Srinivasaraju.

At one event at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), foreign minister YB Chavan was invited to speak. He had already faced some rough questioning by IFD members at a public event in Chicago. Srinivasaraju writes, “There, too, seven to eight IFD members and friends confronted him. All of this was part of the plan. At IIT, they went into a lot more details from the Emergency experience. Chavan was so uncomfortable that what he said at that point could even be perceived as a threat. He said, in SR’s (Hiremath) paraphrase, something like, ‘Come to India and see how democracy is functioning, don’t stand up and argue here.’ To the IFD members, it sounded like ‘come to India, we’ll show you your place.’

Srinivasraju says that the govt was less affected by what the protestors did than by the opinion of western policymakers and media. “Once the American media started featuring IFD protestors, the govt moved swiftly to impound passports of some of the members.” There was criticism from the community too. “One argument raised frequently was ‘ ghar ki badnaami hogi ’ (why wash dirty linen in public?),” Kumar says.

The movement ended after Indira Gandhi announced elections in 1977. Soon after, Kumar’s scholarship was restored and passports of the IFD members released.

The Turkman Gate slum demolition drive

Devanshi Mehta, June 29, 2025: The Times of India

New Delhi : In a cramped corner shop that bears a faded “RK Traders” sign, Rasheed Kamal sits hunched on a plastic stool. The 64-year-old's weathered hands still tremble when he speaks of that morning in 1976. The memory remains as sharp as broken glass, the sound of bulldozers approaching his original shop in Turkman Gate area, policemen with batons raised, a salt water-soaked cloth pressed to his face as he desperately tried to counter the tear gas.

The mayhem at Turkman Gate on May 31, 1976, during the Emergency was sparked by a slum demolition drive launched by Indira Gandhi’s govt, prompted by her son Sanjay Gandhi. The residents of Turkman Gate resisted. Police opened fire on protesters, resulting in many deaths and more injured or displaced. The death toll varies, with different accounts from officials and independent researchers. The central govt imposed a media blackout and the incident was only reported through foreign media outlets. While police officially admit to six death, one officer, Rajesh Sharma, who had issued the firing order to the Central Reserve Police Force, claimed that at least 20 people died in the shooting. Independent researchers have estimated 12 deaths.

“I was just opening my shop at 11am,” Kamal remembered. “We had a small business sorting old newspapers and magazines from nearby publication houses, making envelopes and folders. I saw two policemen approaching, threatening to pull me out. I didn't even have minutes to respond.”

What followed was not merely the demolition of what official records would later dismiss as ‘slums’ and ‘unauthorised settlements”, but a systematic erasure of a living heritage, the destruction of havelis, burial of fountains, silencing of stories that had echoed through old Delhi’s narrow lanes for generations. Hadib-ul Rahman, now 75, said, with both pride and sense of loss, “We are the eighth generation living here. I remember as a child, we would visit the Haveli Hauz Muzaffar Khan here. There were fountains inside. The old people who lived there would call each other fuwara waale (fountain people). There's an entire generation that still calls themselves that, even though no fountain exists anymore.” Today what was once Haveli Hauz Muzaffar Khan is known as Teliya ka Fatak, named after the sellers who moved in later after the haveli, its fountains and courtyards were reduce to just its gate. The irony is heartbreaking, the fuwara waale clinging to an identity rooted in water features that were bulldozed decades ago, their very title an archaeological evidence of what was lost.

Kamal described the scenes in language that reads like war dispatches: “Bulldozers came one after another. People filled buckets with salt water and soaked cloth in it to dab their eyes stinging with teargas. They threw bricks from their own demolished homes at the policemen lobbing teargas shells.” The human cost was devastating. “They didn't consider anyone’s age. They pulled people out, be the person 80 years or 30, from wherever they were hiding and beat them recklessly,” Kamal recollected. Families were scattered; some evacuated to Trilokpuri, others to Nand Nagri. Many spent days not knowing if their loved ones were alive, dead, or in jail.

The economic devastation was as brutal. Expensive utensils, jewellery and heirloom treasures were dumped in Sarai Kale Khan. As families scavenged through garbage dumps looking for remnants of their lives, thieves also arrived to pick through the ruins. Rahman's family went from a 100 sq yard house to a 22 sq yard DDA flat. Kamal had barely spent six months in a new shop, in what is now Vardhaman Plaza, when everything was destroyed. “Every day, I pass by the place and see what our lives could have been,” Kamal mused. “But today I sit in a shop with a barely functioning fan." Mohammad Yasin, who was just seven years old at the time, carries different scars. His family traded in horse carts that collected debris. “I live in a jhuggi now,” he said. “Our family never recovered. I remember eating roti with onion because there was nothing else.” The fear persists. “I'm scared of the demolitions taking place across Delhi. I may become homeless once more,” he shivered.

The Dargah Faiz-e-Ilahi Masjid, which few know also housed an akhara, became a sanctuary during the violence. Abdul Sami, now 70, works at the mosque and recalls how people clung to its gates during the chaos, only some making it inside to safety. The gentle murmur of daily worship today masks the echoes of a bloodier past when bulldozers roamed the streets like mechanical beasts. Perhaps the most poignant testament to the area’s spirit comes from Ishrat, who was 16 in 1976. She narrates a lore that emerged from the tragedy: “When the bulldozers came to the kabristan (graveyard), they stopped at a huge tree and couldn't move forward. Our elders say, ‘ Yahan ki agaam, marte huye aur zinda dono apne haq ke liye ladd rahe thay (Here, both the dead and the living were fighting for their rights).”

This image — of the living and the dead united in resistance against erasure — captures the essence of what was lost, not just building, but the soul of a community. Today, where lively havelis once stood, vertical DDA flats rise like tombstones over buried history. The area that Rahman’s son, Mohammad Nafeez, knows only through his father’s stories bears no resemblance to the rich culture that once flourished here.

The official narrative is about ‘slum clearance’ and ‘urban development’. But the survivors tell stories of heritage buildings reclassified as unauthorised structures, cultural identities bureaucratically obliterated, communities bulldozed into silence. Five decades later, no redressal has come. The elderly survivors carry their stories like heirlooms — the only inheritance that couldn't be bulldozed.

Rasheed Kamal’s final words echo with the weight of unhealed wounds: “ Jab tak inka dil chaha, tab tak inhone bulldozer chalaya (They operated the bulldozers as long as their hearts desired). To this day, we are unable to rebuild that life or regain our wealth.”

Turkman Gate continues to stand as a reminder of what development can cost when it proceeds without memory, when the living heritage of a city is sacrificed to the god of urban planning. The fountains are gone, but the fuwara waale remain, though as ghosts of their own demolished past, keepers of stories that refuse to die.

Kamal Nath’s recollections

RITU SARIN, June 28, 2025: The Indian Express

I look at it as a period when the country was very disciplined. Of course you had the downside of the arrests and the detentions. But we must understand: all the trains worked on time, everything was on time. There was discipline and the law and order was perfect. As I said, there was the downside of the arrests. I still remember, there were huge law and order issues across the country at the time when the Emergency was imposed. I recall Mrs Indira Gandhi toying with the idea and (West Bengal Chief Minister and close Indira aide) Siddhartha Shankar Ray and (Congress president) D K Barooah etc insisting that we declare the Emergency. And Sanjay (Gandhi) saying, yes, there is no other choice.

* How long before the actual proclamation of the Emergency were you aware that something like this was going to happen? After all, it was a very small circle of people who knew…

I was at their house when the decision was taken… I was at the Prime Minister’s house. I think it was on June 24, the day before. And then the thing was to alert everybody and indicate that something is going to happen without saying it would be the Emergency. I did not understand the Constitutional position and got to know of it only at that time. On the 24th, besides me, there were Ray, Barooah and, as far as I remember, (Congress leader and Indira aide) Rajni Patel.

Do you think the country can ever see the imposition of the Emergency again?

It is already happening. You are seeing how the press is being throttled. You must admit it. You are seeing how TV channels are being suppressed. At that time you did not have so much TV as we have today. You are seeing how journalists who are speaking their mind are being suppressed. And I do not even have to say what is happening to other democratic institutions. It is all very apparent what’s happening today.

How do you see the role of the media during the Emergency? You were appointed as a government nominee on the Board of Directors of The Indian Express…

I must say I had a lot of respect for Mr Ramnath Goenka; B D Goenka, his son, was a friend of mine. When Ramnath ji had a heart attack in 1976 and was admitted to a hospital in Kolkata, I went to meet him. I held his hand and said to him, ‘I will hold no Board meetings until you are out, because we want to make you a party to all the decisions’. Then there was the issue of (The Indian Express senior journalist) Kuldip Nayar, who was in jail. I told Sanjay that he must be released.

In her book on the Emergency, Coomi Kapoor, who was then in The Indian Express, wrote that you confirmed to Nayar that Indira Gandhi was going to announce the general elections in 1977. What is your recollection of this episode?

Yes, yes. Mrs Gandhi was always for calling elections. She said we have had enough of this. I could see it in her tone and tenor — that she wanted to call the elections. I remember around New Year’s time, in December 1976, Sanjay and I had gone to Srinagar. At that time there were no cellphones. He booked a call to Mrs Gandhi, and she told him, come back immediately. So Sanjay flew back. And then she told him, ‘I am going to lift the Emergency’. He said no. She said, ‘I am going to have elections’. He said, ‘No, you should first lift the Emergency and then call elections’. She said, ‘No, I will first call elections’. And the first thing Mrs Gandhi did after the elections, when she lost, was to call a Cabinet meeting and lift the Emergency.

What is your view of your friend Sanjay Gandhi as a politician?

Well, he was misunderstood because he was a person who worked 18 hours a day. Right? He was fanatically nationalistic. So people sometimes misunderstood him. And his family planning (scheme)… they (the people) thought this was very heavy handed. But it was necessary for the country because of the bursting population. And he is the one who gave the slogan ‘Hum do, hamare do’.

Sequence

1975: Indira wanted to tax farm income

From the archives of The Times of India

April 10, 2013

Indira Gandhi was willing to go where politicians today fear to tread. Back in 1975, she wanted to tax agriculture income and the rural rich. It remains a no-go area for policymakers even today.

Addressing the Institute for Social and Economic Change in Bangalore, which was reported by the US mission in India, revealed by WikiLeaks, she reportedly asked the states “to overcome the compulsions that have stopped them from taxing agriculture income and the rural wealthy. She particularly deplored subsidies on water and power used for irrigation. She warned the states they would not receive any overdrafts if they overspent.”

While these might sound free-market thinking, Gandhi took a different stance by saying `the "income tax department is being asked to intensify its efforts to bring self-employed professionals and traders within the tax net,’ without indicating how this was to be done.” She also warned industrial borrowers that they were being watched closely, justifying the credit squeeze on the private sector.

A timeline

Adrija Roychowdhury, June 25, 2023: The Indian Express

“The President has proclaimed the Emergency. This is nothing to panic about. I am sure you are all aware of the deep and widespread conspiracy, which has been brewing ever since I began to introduce certain progressive measures of benefit for the common man and woman in India.”

With the announcement of these words on the All India Radio, prime minister Indira Gandhi declared the historic moment of Emergency in 1975. Analysed in retrospect to be one of the darkest period of post-independent Indian history, the two-year-long period of Emergency was also perhaps the most momentous episode in the political evolution of the Indian National Congress.

Referred to as ‘the matriarch’ by historian Ramachandra Guha, Indira Gandhi had an uncomfortable relationship with democracy, a fact that is evident from several documented conversations of hers. Guha reproduced in his book, “India after Gandhi” a dialogue between Gandhi and her friend in 1963 wherein she said that “democracy not only throws up the mediocre person but gives strength to the most vocal howsoever they may lack knowledge and understanding.”

Gandhi’s rise to the role of Congress president and then to the position of prime minister was accompanied by every effort on her part to gain absolute control over the government and her party. Her authoritarian stance was aided by her charismatic appeal, particularly among the middle class and the economically downtrodden who considered her to be the one who could rescue them from their economic problems. The Emergency, for Gandhi was her strongest attempt to shut out every democratic voice and tighten her authoritarian grip.

Announced soon after the Raj Narain verdict, wherein the Supreme Court barred Gandhi from voting, the Emergency was one of the harshest clamp down on her political opponents and the media. The politico-economic situation including the recently concluded war with Pakistan, the 1973 oil crisis and the drought in the country, did everything to creating conditions perfect for Gandhi’s proclamation. Steeped in the urgent need for economic development, the Emergency allowed Gandhi to carry out mass arrests of ministers and have complete control over what the media published. It also resulted in her son, Sanjay Gandhi carrying out forced sterilisation drives in Delhi and slum clearance programs. Consequently, it was also the time of large scale protests against the dictatorial methods of the government. Foremost among them were the demonstrations organised by Jayaprakash Narayanan. Media outlets including The Indian Express and The Statesmen protested against the undemocratic conditions in the country. By the end of the two years, Gandhi had been at the receiving end of huge amount of criticism, both from her country’s people and from world leaders. Finally, in March 1977, India was freed from the clutches of Emergency.

Here is a timeline of important events in the Emergency of 1975:

January 1966: Indira Gandhi elected prime minister.

November 1969: The Congress splits after Gandhi is expelled for violating party discipline.

1973-75: Surge in political unrest and demonstrations against the Indira Gandhi-led government.

1971: Political opponent Raj Narain lodges complaint of electoral fraud against Indira Gandhi.

June 12, 1975: Allahabad High Court found Gandhi guilty over discrepancies in the electoral campaign.

June 24, 1975: Supreme Court rules that MP privileges to no longer apply to Gandhi. She is barred from voting. However, she is allowed to continue as Prime Minister.

June 25, 1975: Declaration of Emergency by president Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed on the advice of Indira Gandhi.

June 26, 1975: Indira Gandhi addresses the nation on All India Radio.

September 1976: Sanjay Gandhi initiates mass forced sterilisation program in Delhi.

January 18, 1977: Indira Gandhi calls for fresh elections and releases all political prisoners.

March 23, 1977: Emergency officially comes to an end.

This article was first published on June 26, 2017.

1976: Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed resented Indira

From the archives of The Times of India

April 10, 2013

Fakruddin Ali Ahmed, the rubber stamp President during the Emergency era, may not have been a complete rubber stamp after all. According to a US embassy cable sent on August 6, 1976, the mission said, “We have heard much more reliably (than rumours) that Fakruddin is seriously concerned over the govt’s family planning moves.” The cable said the rumours have been about “some disaffection between the Prime Minister and President Fakruddin Ali Ahmed. The stories vary but have as their central core that Fakruddin is concerned that the PM and her son are pushing too hard on the political and constitutional system of India.”

Impact

Film industry

Overall impact

Sampada Sharma, Jan 20, 2025: The Indian Express

Many filmmakers who had a financial stake chose to toe the government's line. However, a few like Dev Anand, Kishore Kumar and Manoj Kumar refused to be dictated to during the Emergency.

The year 1975 was one of the most pivotal years for Hindi cinema. Films like Sholay, Deewaar were running to packed houses, Jai Santoshi Maa had surprised everyone by becoming the most profitable film of the year, and the likes of Chupke Chupke and Choti Si Baat came as a breath of fresh air amid the action-heavy films. But, this was also one of the darkest times for Hindi cinema, and led them into uncharted waters. It was in February of 1975 that Gulzar’s film Aandhi released in theatres. The film’s protagonist, a woman who aspires to be a successful politician had an uncanny resemblance to the then Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi, and this didn’t go down well with powers that be. Some of the film’s promotional material also drew parallels between the PM and the lead character. After weeks of release, the film was pulled down from the theatres and banned. The ban came in place just a few weeks after Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had imposed a state of Emergency in the country, which, among many other things, censored the press and forced them to bow down to the government.

The ban on Aandhi was just the beginning as for the next 21 months, the Hindi film industry was expected to dance to the tunes of the government. If they refused, or showed any kind of unwillingness to participate, there were consequences and many artistes of great reputation including Kishore Kumar and Dev Anand, faced the brunt for their opposition. This was also the era of Salim-Javed and while in hindsight, their character of the ‘angry young man’ is seen as the voice of anti-establishment, their most popular work Sholay also faced some resistance from the censor board for being too violent. As per actor-filmmaker Manoj Kumar, he was the one who persuaded the then I&B minister VC Shukla to pass the film.

In later years, Shukla was seen as an authoritarian. Films submitted for censor certificate lay in limbo for months and the shortage of raw stock made it difficult for producers to continue their work. As per an India Today report of 1977, after Emergency was lifted, producer GP Sippy said that for the last 21 months, the film industry had lived “under the atmosphere of threat.” Rules of censorship about showing violence on screen changed every few weeks, the broadcast rules for All India Radio and Doordarshan were just as inconsistent but what did not change was the insistence from the government that artistes with a strong voice act as their spokespeople.

Kishore Kumar banned for not bowing down to Sanjay Gandhi

It is rather well known that Kishore Kumar’s songs were banned from All India Radio during the Emergency era as he refused to bow down to the powers that be. But what exactly happened that led to this ban? The ban first came into effect in January 1976, six months after the Emergency began. Indira’s son Sanjay Gandhi, who was all-powerful in the government, had come up with the idea of a radio programme called ‘Geeton Bhari Shaam’ to promote the government’s schemes. Kishore Kumar was contacted to participate in this charade but the temperamental singer refused. In the biography titled ‘Kishore Kumar: The Ultimate Biography’ by writers Anirudha Bhattacharjee and Parthiv Dhar, it is suggested that at this time, Kishore put his foot down and was ready to sing on the streets with a harmonium, but was not willing to play ball with the administration. He is quoted saying, “I did what I thought best. Singing at private functions is definitely not an anathema. With genuine love and respect, I am only too eager to bend. However, if someone decides to rest his foot on my head, he will not have the good fortune to witness the best of my courtesies.”

The ban, however, lasted for only six months and ended in June 1976 in a rather poetic way as AIR played his song “Dukhi Mann Mere.” But, the terms of their compromise, however, are rather hazy. It is suggested the VC Shukla and Kishore Kumar’s families had connections through Khandwa, the singer’s birthplace, and it was via this channel that an olive branch was extended. But, an India Today report of 1977 suggests that Kishore had, in fact, been made to apologise. His older brother Ashok Kumar had tried to mend the situation by meeting Indira Gandhi but this had not helped their cause. To put matters to rest, and not generate more buzz out of Kishore’s rebellion, a compromise was reached.

Dev Anand ‘vehemently’ opposing propaganda, getting banned

Co-incidentally, the song that lifted the ban on Kishore, “Dukhi Man Mere”, was filmed on actor Dev Anand for his 1956 film Funtoosh. And Dev too, faced a similar ban for not abiding by the government’s diktats during the Emergency era. In his book, Romancing with Life, Dev Anand said that he found himself, along with Dilip Kumar, at a government organised event in Delhi and felt that this activity was being conducted to boost the image of Sanjay Gandhi, who was being projected as ‘desh ka neta’ at the time. The presence of film industry stalwarts was to make sure that they spoke highly about the proceedings. Dev, however, refused to do so.

Dev recalled that while “Dilip also hesitated to go to the TV centre to participate in any propaganda in favour of the Emergency, I vehemently and vociferously opposed the suggestion.” The result was something he had already expected. “Not only were all my pictures banned from being screened on television, but also any mention of or reference to my name on an official media was forbidden,” he wrote. All of Dev’s releases were banned for the time being and as he spoke to VC Shukla about the same, he was told to speak in favour of the government in power, or he would have to face the repercussions.

Along with Dev, his brothers Chetan and Vijay also opposed Emergency, termed as the darkest time in post-independence India. Vijay Anand told India Today that the film industry would have “collapsed” if VC Shukla got to have his way for a few more months as the movie producers were tired of “making and re-making their films” just to they could please those on top. He also said that films that showed Chandrashekhar Azad and Bhagat Singh as heroes were banned during this time for fear that this could inspire people to stand against the authoritarian regime.

Soon after the Emergency was over, Dev lent his support to Janata Party but after that government failed to keep up their promises, Dev came up with the idea of starting his own political party, National Party. However, the party was disbanded a few months later.

Manoj ‘Bharat’ Kumar asked to make a pro-Indira Gandhi film, ends up suing the government

Manoj Kumar, popularly known as Bharat Kumar, had made a career out of making nationalistic films. Perhaps, that is why, he had the image of being the person who would become the government’s mouthpiece when they needed him the most. Manoj had famously made the 1967 film Upkar after the then PM Lal Bahadur Shastri requested him to do so. During the Emergency era, Manoj was in talks with PM Indira Gandhi for a film on Emergency. As per the actor’s admission to Lehren, he got Salim-Javed involved in the scriptwriting process. But, the film was shelved.

Years later, in a chat with Hindustan Times, Manoj said that the film was called Naya Bharat and he had discussed the script of the film with Indira and her son Sanjay. “At first, they loved the script. She even agreed to make a special appearance in it. But a few months later, they said that she could only give her voice in the film. The script had to be changed and I was not okay with that. So I cancelled everything and the film was eventually shelved,” he said. Manoj did not elaborate on what changes were expected from him that led him to abandon the project.

Manoj’s problems with the government started after this as he found himself in a position where he had to sue the government. In the same chat, he claimed that for a short while during the 21-month period, films could be telecast on television just two weeks after their theatrical release, which affected the business of a few of his films. Manoj said that the re-release of his 1972 film Shor suffered as the government decided to broadcast it on television shortly before the theatrical re-release, and his 1976 film Dus Numbri suffered similar consequences. Due to this, he faced some heavy losses. “We decided to take this to court where I eventually won the case,” he said.

From having the ear of the I&B Minister where he believed that he had enough say to get Sholay cleared by the censor board, to standing against the government in a court of law, Manoj went through many ups and downs in this 21-month period.

Since the press was heavily censored during the 21-month period, the goings-on within the film industry weren’t always fully reported. Many filmmakers who had a financial stake chose to look the other way as the government dictated terms. But, there were a few who made sure that they stuck their ground and even if they faced some opposition at the time, they certainly emerged as rebels.

Kishore’s voice was muzzled

The ministry, headed by Indira Gandhi’s aide V C Shukla, wanted Bollywood to help promote on All India Radio and Doordarshan the 20-point programme Indira had declared after imposing Emergency and had called top filmmakers to see how their ‘co-operation’ could be obtained. Kishore Kumar, whose popular voice the regime sought to support its actions, wasn’t budging.

CB Jain, then I&B joint secretary, telephoned him, told him what the government wanted and suggested they meet at the singer’s residence. He refused, according to the report of the Shah Commission later set up to probe Emergency excesses, saying he was unwell, had heart trouble, and was advised by his doctor not to meet anyone. He told Jain he didn’t want to sing for radio or TV “in any case.”

Offended, Jain told his boss, I&B secretary SMH Burney, the singer was “curt” and “blunt” and called his refusal to meet “grossly discourteous,” the Shah panel noted. Burney, with minister Shukla’s sanction, then passed an order banning all Kishore Kumar songs AIR and Doordarshan, listing films he was acting in for “further action,” and freezing sales of his gramophone records.

The inquiry panel said the I&B secretary’s subsequent noting that the action had a “tangible effect on film producers” showed it was meant not only to “teach Kishore Kumar a lesson” but to coerce others into submission. The commission called it “a clear case of vindictiveness… against a film artiste of renown.” The muzzling worked at a time the government had curtailed freedoms and imprisoned its opponents.

On July 14, 1976, the panel recorded, Kishore Kumar wrote a letter to the ministry saying he was willing to co-operate. In view of this “undertaking,” Jain wrote, “we may lift the ban.” But they wouldn’t just let the singer be. “Watch the degree of co-operation that he extends,” Jain mentioned in the note.

Summoned by the inquiry commission, Shukla said he took full responsibility for the “regrettable episode” and said “no officer should be blamed,” TOI reported on October 29, 1977. But retired SC chief justice J C Shah found it “shocking” that “a person should be treated in this manner for not falling in line.”

The matter ended, as the Janata Party government that set up the commission collapsed; Kishore Kumar’s voice, though, managed to stand the test of time.

Fundamental rights

The Times of India, Jun 25 2015

Manoj Mitta

Darkest phase of India's history - when SC failed to uphold fundamental rights

It was 40 years ago that Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, bypassing her own Cabinet, asked President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed to sign the Emergency proclamation. He did so promptly , late on June 25, 1975, without in the least serving as a check on executive overreach. The circumstances were fraught as Indira had just received an interim reprieve from the Supreme Court to carry on in office despite being convicted in an election case by the Allahabad high court. All that her “top secret“ letter to Ahmed offered by way of justification for seeking such unprecedented action was some information suggesting that “there is an imminent danger to the security of India being threatened by internal disturbance“. But this claim of hers has since been nailed by the disclosure of the official file under RTI. This file does not contain a shred of material backing such threat perception on that fateful day .

On the contrary , it reveals that the first assessment of an alleged threat of internal disturbance was made more than a fortnight later in the form of a report on the situation before and after June 25 from the IB submitted on July 11. Thus, India's hard-fought democracy was suspended on the say-so of one individual, without a modicum of institutional safeguards.

The dubious origins of the Emergency set the tone for a range of draconian measures that were taken over the next 21 months by not just government functionaries but also extra constitutional authority Sanjay Gandhi. With almost the entire Opposition in jail, Parliament could do little to stop the executive from committing excesses. This is how the notorious 42nd Amendment was passed in Parliament, claiming unfettered authority to change the Constitution in the teeth of the basic structure doctrine propounded by the Supreme Court.

The apex court showed little courage to enforce accountability or uphold fundamental rights when it came to the crunch. In fact, it earned an opprobrium it could never shake off for its judgment in the habeas corpus case. While uphold ing detention orders from across the country , the apex court ruled in ef fect that even the fundamental right to life and personal liberty stood suspended during Emergency . Out of the five judges who dealt with that notorious case, the only one who dissented, Justice H R Khanna, was immediately superseded from being appointed as Chief Justice of India.

Those who were not in jail had to cope with an oppressive regime, reminiscent of the worst of colonial times. The various freedoms en shrined in Article 19 freedom of speech and expression, freedom to assemble peaceably , freedom to form associations or unions were a major casualty . The crackdown on dissent was such that the government even introduced censorship of the press. That dark phase of India's history bears many lessons in governance, accountability and the rule of law, lessons that are as relevant today as they were then.

Forced sterilisations

The Times of India, Jun 21 2015

Avijit Ghosh in Uttawar, Haryana

A tale of two villages that saw the ugliest face of the Emergency

The Emergency meant different things to different people. For editors it was a daily battle with censorship. For politicians, barring Congressmen and some Leftists, it was time to go underground or to jail. For cops it meant absolute authority , thanks to the dreaded ordinance, MISA (Maintainence of Internal Security Act).

But for Uttawar village, 60 km south of Delhi, the Emergency will always be about one unnerving morn ing in the bitter winter of 1976 when hundreds from the Muslim-dominated village were packed into buses and taken to police stations, where they were thrashed, jailed and forcibly sterilized.

If the 1975 Emergency was a black mark on India's democratic register, forcible sterilization was its ugliest public face. And two Haryana villages, Uttawar and Pipli, lived its horror.The drive stemmed from the wisdom that parivar niyojan or family planning was imperative to prevent population explosion. But the implementation had communal undertones too.

Now part of rejigged Haryana's Palwal district, Uttawar is in Mewat region largely inhabited by Meo Muslims. Many are marginal farmers or daily wagers.

Uttawar had substantial Congress voters but the Emergency turned them against the No. 1 national party .In the 1977 Lok Sabha polls, the entire village voted for Janata Party.

September 1976

Sep 5, 2021: The Times of India

1.7 mn sterilised in September 1976

Among the excesses of the Emergency era from 1975 to 1977 under Indira Gandhi was the policy of forced sterilisations, of which Sanjay Gandhi was a major proponent. Fear of overpopulation made ‘family planning’ a key policy plank, with Sanjay Gandhi claiming in interviews that his policies would solve “50% of our problems”. Though sterilisation camps were active around the country since the early 1970s, the policy was escalated in 1976 — first, the government offered financial incentives to those voluntarily opting for sterilisation, particularly if they already had at least two children. But in September 1976, there were reports of forced sterilisations, especially in rural regions, followed by several protests in Delhi and UP. In September 1976 alone, 1.7 million people were reportedly sterilised. In one incident, local officials targeted Muslims in Muzaffarnagar, near Delhi, which led to a riot and at least 50 deaths. Between 1976 and 1977, 4.3 million people were sterilised, exceeding the government target by 190%. Under the Fifth Five-Year plan, from 1974-1979, more than 18 million people were reportedly sterilised. After the Emergency was lifted in January 1977 and an election was called, Congress was handed its first general election loss. Indira Gandhi would go on to defend her son, saying he was not to blame for the excesses of Emergency.

Source: TOI Archives, media reports

Expressing dissent discreetly

The Times of India, Jun 26 2015

When a smartly worded obit exposed death of democracy

“O'Cracy, D.E.M., beloved husband of T. Ruth, loving father of L.I. Bertie, brother of Faith, Hope and Justicia, expired on June 26.”

It was a small obit, only 22 words long, which came out among the classified ads in the Times of India on June 28, 1975, three days after the Emergency was declared.

Seemingly innocuous at first glance, the words escape censure from the clerk at the TOI office in Bombay . But when carefully read, they turned out to be a sly expression of dissent against the imposition of the Emergency .

Forty years ago, journalist Ashok Mahadevan, only 26 years old then, used subterfuge and smarts to register his protest against censorship typifying those dark days of democracy in post-independent India. Mahadevan, who used to work for Reader's Digest then, had come across a brief news item of similar nature in the popular magazine. The filler, originally published in a Sri Lankan newspaper, ran into several paragraphs. Not surprising when you consider that the first half of the 1970s was marred by violent internal strife leading to an Emergency-like situation for several years.

5 laws

See graphic:

5 major laws enacted during the Emergency (1975-77)

On Delhi’s campuses

Sugandha Jha, June 26, 2025: The Times of India

New Delhi : The plan became routine. A trusted friend would lock a hostel room from the outside and slip the key into his pocket, making it seem empty. Inside, a student would wait silently — one of the many in hiding across Jawaharlal Nehru University after the Emergency was declared in June 1975.

Every day, the hideouts shifted. No one stayed in one place for too long. It was a campus under watch, where friends became jailers and silence was survival. But one evening, the friend — a student from neighbouring IIT Delhi — forgot to return. The next morning, a knock came. Loud. Deliberate. The student inside opened the door, unaware — and was arrested.

Inside that room was Sohail Hashmi, now a noted historian and cultural activist, who was then a young student evading a govt crackdown on dissent. This was Emergency-era JNU — a campus of barricaded doors, whispered alerts, and quiet defiance. As Indira Gandhi’s govt suspended civil liberties and jailed opposition leaders, students at JNU became some of the most organised and persistent voices of resistance. What unfolded in those years is now etched into campus memory as both a story of rebellion, and of personal loss. Hashmi recalled how an underground system sprang into action. News of an imminent police raid to arrest student activists was leaked by one of the police informers, a man the students had befriended. “The university turned into a fortress. Any anti-establishment slogans or posters were torn down. There were three layers of armed police along the ridge,” Hashmi said. “They crouched behind Aravalli rocks with guns. Some of them walked among us, dressed as students. Police informers were everywhere. Still, we found ways to resist.”

An informal yet sophisticated system was set up. Rooms were shuffled, hideouts rotated, and locking duties assigned to volunteers. A code of silence emerged. No one talked. Underground bulletins criticising the govt, covering national and campus news, were typed, stencilled, and quietly slipped under hostel doors at night. “We used stencils to print hundreds of copies of the paper called The Resistance. To date, the police have not found out where we printed it on campus,” Hashmi said.

One arrest, he remembers vividly. “We organised a university shutdown, but Maneka Gandhi, daughter-in-law of the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, insisted on taking her classes. The students tried to stop her. She later complained that she was obstructed,” he said. “Soon after, an Ambassador car drove into the campus. A tall man stormed out, dragged Prabir (Purkayastha) by his collar, and shoved him into the car. They came looking for DP Tripathi, but took Prabir by mistake,” he added, with a slight laugh.

Purkayastha, a student at JNU, spent the remainder of the Emergency in jail under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA), a draconian law that allowed imprisonment without trial. In Delhi, the Emergency came down like a hammer. On June 25, 1975, Prime Minister Gandhi declared the Emergency, citing threats to internal security. Thousands of political opponents were jailed overnight. Press freedoms were curtailed, civil liberties suspended. Universities such as JNU, where leftist student unions flourished, quickly became targets of the state.

Not all arrests were accidents. Some were pre-emptive. Communist leader and former SFI activist Prakash Karat, a key figure in student politics, said he wasn’t even in Delhi when the Emergency was announced. “I was warned in advance that they would be looking for me, so I went underground,” Karat said. “Later, we organised a three-day strike and shut down the campus. The vice-chancellor suspended many students and blacklisted others from readmission.”

He added, “The strong sentiment against the Gandhi govt's policies had long been brewing. In Bihar, the JP movement emerged as an uprising against corruption and misrule. In West Bengal, the Left fiercely resisted central authoritarianism. There was a growing mood of defiance across the country.”

Even under intense surveillance, students found subtle yet potent ways to protest. One such moment came during a university event where the then education minister was invited as the chief guest. “A circular was informally issued — no slogans, no disruptions,” a former student recalled. “We sat quietly throughout the programme. But the moment the minister stood up to speak, the entire audience, except university officials, silently rose and walked out. It was a mass protest in silence.” Not every story from that time was one of revolution. Some carry the weight of deep personal pain. Ranjana Kumari, now a prominent women’s rights activist, said: “I was a student and got arrested. I spent one night in custody at Hauz Khas police station with my boyfriend, now my husband. My younger sister was arrested too. She spent six months in jail in Varanasi. My father had a heart attack and died from the stress. The whole family suffered as we fought for democracy and freedom.”

Fifty years later, those who have lived through the Emergency remember the paradox of that era. There was fear, yes, but there was also an unrelenting desire for liberty. At JNU, this took the form of camaraderie and codes, of calculated risks and whispered resistance. Today, the corridors of the university echo with newer debates. But the stories from 1975 still resurface. A time when rooms became safe houses, students walked out in silent protest, and a generation that refused to be silenced. One message these alumni have for the new generation of student activists is: “Stand up for your rights.”

Opposition

Young opponents of the Emergency

The Times of India, Jun 21 2015

Arati R Jerath

In those heady days of agitations, a whole new crop of leaders emerged. Today, they're key figures on the political landscape

Indira Gandhi's Emergency was a water shed moment for Indian politics and poli ticians. The unprecedented suspension of democracy heralded the demise of the Congress system that had dominated and Congress system that had dominated and shaped India in the years immediately following Independence. As space opened up for nonCongress alternatives, it spawned a whole new crop of leaders who not only redefined Indian politics but continue to hold sway even today , 40 years after that dark day when the state imposed its will on an unsuspecting polity . Ironically , many of them, particularly those who emerged from Jayaprakash Narayan's student movement, are accidental politicians. The current finance minister and BJP leader Arun Jaitley and the Bihar chief minister and JD (U) leader Nitish Kumar for instance, candidly admit that they may never have joined full-time politics had they not been sucked into the heady JP movement. Kumar was a student leader in Patna University . “I never thought I'd become a full-fledged politician then,“ he says. “I was inspired by JP and joined his movement.“ And when Emergency came, Kumar, like thousands of other student activists, went underground, only to be ferreted out and jailed.

His time in prison strengthened his interest in politics. An avowed socialist, Kumar recalls that he and other incarcerated leaders held classes for the uninitiated in the jail, enlarging their pool of supporters. “It was easy for us, he laughs. “Most of the youth in prison were drawn to our socialist ideology. RJD chief and former Bihar chief minister Lalu Yadav is another prominent leader who cut his political teeth on the Emergency . Also a student activist during his days in Patna University , he had given up politics to join a veterinary college as a clerk. And then the JP movement called. He enrolled himself in a law college to become a student again so that he could be a part of the heady agitation that engulfed campuses across the country . He became president of the Patna University Students Union which formed the Bihar Chhatra Sangharsh Samiti to spearhead JP's fight against rising prices, corruption and the Indira regime.

Like most mass movements, students were the backbone of the JP movement. Protests and street agitations honed their political skills. The crackdown during Emergency only strengthened their resolve and shaped them into the leading figures they would become in the years that followed. The contemporary political landscape is dotted with activists from that time: Venkaiah Naidu, Rajnath Singh and Ravi Shankar Prasad are ministers in the Modi government today while those who came from the socialist stream like Mulayam Singh Yadav rule the roost in UP and Bihar.

Former Delhi University professor of political science Neera Chandhoke points out that the JP movement was a broad-based platform for all types of disgruntled elements drawn from different political ideologies. “JP tapped into a moment of deep discon tent, much like Narendra Modi and Arvind Kejriwal. Unfortunately , he failed to provide an alternative to the Congress system,“ Chandhoke says. Internal contradictions ultimately led to the disintegration of the Janata Party .But that moment in history paved the way for the Mandal versus Mandir politics that has dominated the Indian arena since the 1980s.

Students apart, Emergency proved a boon to political leaders like Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Charan Singh and trade union leaders like George Fernandes who perhaps would have been confined to the sidelines, overshadowed by a pre-eminent Congress with its galaxy of leaders from the freedom struggle. Vajpayee rose to become the first BJP prime minister and the first non-Congress PM to complete a full term in office. Another stalwart from that era is former Union minister and JD(U) leader Sharad Yadav. He was one of JP's blue-eyed boys, chosen to contest a bye-election from Jabalpur in 1974 using the farmer-in-a-wheel symbol on an experimental basis. He won from what had been a Congress stronghold and the symbol became the Janata Party's winning card against Indira Gandhi in 1977.

He says the differentiator between the Emergency generation of political leaders and today's Gen Next politicians is political commitment. “We grew up at a time of strong ideologies. We believed in nation building, civil liberties and democracy . Now we have the post-liberalization generation of politicians who are ideology-neutral. Sadly , politics has become a money-making profession today , he says.

M Karunanidhi, CM, TN: a reluctant opponent?

June 23, 2023: The Times of India

In Tamil Nadu, chief minister MK Stalin once remarked that the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP’s) rule is “authoritarian” and “worse than the Emergency”. So, what happened in Tamil Nadu during the Emergency?

In Tamil Nadu, Congress (O) leader K Kamaraj had fretted that the nation was lost. He died a broken man on October 2, 1975. All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) leader MG Ramachandran and the Communist Party of India welcomed the Emergency, narrowing the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam’s (DMK’s) options. The Communist Party of India (Marxist) opposed the Emergency.

Pushed to a corner, the ruling DMK chose to oppose the measure. Political satirist Cho Ramaswamy described DMK president and then chief minister M Karunanidhi as “a reluctant opponent” who later “put on the mantle of a great fighter against the Emergency”.

Yet, Karunanidhi failed to stave off his government’s dismissal on January 31, 1976, and the subsequent jailing of hundreds of DMK men, including his son Stalin and nephew, the late Murasoli Maran.

On June 26, 1975, and well through to the next morning, Karunanidhi was closeted with DMK general secretary Era Nedunchezhian and treasurer K Anbazhagan on what ought to be the party’s response. The party executive took up the Karunanidhi-crafted resolution, which described the Emergency as the “inauguration of dictatorship”.

Despite fears expressed by a section of the executive that opposition would lead to the government’s dismissal, the resolution was adopted unanimously by 63 of the 75 members present.

Party mouthpiece Murasoli carried the headline “Indira Gandhi becomes a dictator” with a cartoon depicting her transformation into the Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler.

There was no going back now. In 1994, Karunanidhi claimed that a central minister (most likely C Subramaniam) came home to advise him to retract the resolution and, in return, promised his government’s extension. Karunanidhi said he chose not to bend. But the relationship with the Congress (I) was beyond mend, and the Emergency was just the last straw.

A calculated move

Karunanidhi had taken care to see that the opposition was not from his administration — hence the resolution had emanated from the DMK executive. But these nuances were lost on Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who was under a siege mentality.

On October 30, 1975, when AIADMK’s P Srinivasan wondered in the legislative assembly why he had not moved an official resolution, Karunanidhi famously replied, “A warrior would know which hand should hold the sword and which the shield.” The speech issued as a booklet titled Sword and Shield was banned the following year.

On July 1, 1975, the prime minister announced the 20-point programme to rein in prices and alleviate rural indebtedness. Karunanidhi welcomed it, hoping for further “progressive measures” including nationalising major industries. However, three days later, Maran told the US consul general in Chennai that the DMK was prepared for the long haul, that Indira was wooing Kamaraj, for with him beside her, she would feel emboldened to strike at the DMK. On the other hand, if the DMK and Kamaraj were to join forces, she “will not be able to control the situation in TN”. That day, Kamaraj fretted to Karunanidhi and Nedunchezhian that he felt the “country is lost”.

Two days later, the DMK’s top three addressed a gathering at the Marina in Chennai where Karunanidhi clarified that the rally’s purpose was to “safeguard democracy” and not to criticise Indira.

However, Karunanidhi’s speech was laced with biting sarcasm. Pointing out that the “great change” of 1969 (when banks were nationalised and privy purses abolished) would have gone astray if not for the DMK, he said: “VV Giri was elected President! Indira madam could continue in office” because of the DMK. “What would have happened to India” if the DMK had chosen to hold back then, he posed rhetorically. “The DMK is accused of treason. We gave ₹6 crore for the 1971 war fund. Is that treason?”

Karunanidhi said that the DMK government had launched and implemented 15 points of the 20-point programme years ago. He noted that 30,000 houses for Adi Dravidas and plans for 5,000 houses for fishermen were underway and that the 20-point programme fell short compared to the DMK’s vision.

A year later, in August 1976, he would claim that his party had felt “heartfelt love” for the 20-point programme and “no one could match the DMK to propagate it”.

Protecting democracy

In the end, Karunanidhi administered a solemn pledge in DMK founder CN Annadurai’s name to those assembled at the Marina “to protect Indian democracy under any circumstances and in any eventuality”.

Only six weeks later, Karunanidhi would extend an olive branch to Indira when on August 9, 1975, at the party’s fifth

Tirunelveli district conference, Anbazhagan proposed and Nedunchezhian seconded a resolution calling on Karunanidhi to undertake efforts to “change the extraordinary situation” by engaging chief ministers and meeting the prime minister. On September 13, the US consul general noted the ambivalence and how the “DMK has been walking both sides of the street”. “Karunanidhi termed the Emergency ‘good’ last month. His recent trip to New Delhi, although still somewhat shrouded in mystery, represents further erosion of his early [in the Emergency] stand against the prime minister’s actions,” noted the consul general.

On December 15, 1976, on Karunanidhi’s invite, leaders of the Opposition from the Congress (O), Bharatiya Lok Dal, Jan Sangh, Praja Socialist Party, Revolutionary Socialist Party and Akali Dal met at DMK member of Parliament (MP) Nedunchezhian’s residence in New Delhi. Ashok Mehta, AB Vajpayee and Biju Patnaik were present. Karunanidhi later recorded that “no one can deny that this was the first and foremost reason for the birth of the Janata Party”.

In his welcome address, Karunanidhi said that a way must be found to normalise the situation in the country. On some placing conditions regarding talks to lift the Emergency, Karunanidhi sagely said conditionalities from either side would be unhelpful.

The next day, leaders continued meeting at Swatantra Party leader HM Patel’s house, where a communique indicating their readiness for talks with the government was finalised.

Karunanidhi forwarded it with a letter to Indira. It is unclear whether she responded to this letter. However, events cascaded fast, and Indira felt confident enough to announce elections and release the arrested leaders.

Through a critical lense

A foot soldier’s memories of jail

Avijit Ghosh, June 26, 2025: The Times of India

The evening after Emergency was declared, a small band of socialists secretly met at a tented coffee house, now gone, in Connaught Place’s Central Park. The purpose was to chart out future political action. Rajkumar Jain, then 29 years old and an ardent follower of the charismatic socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia, was part of that select group.