Dhanuk, Behar

Contents |

Dhanuk, Behar

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Tradition of origin

A cultivating caste of Behar , many of whom are employed as personal servants in the households of members of the higher castes . their origin is obscure. Buchanan considered them a "pure agricultural tribe, who, from their name, implying archers, were probably in former times the militia of the country, and are perhaps not essentially different from the Kurmis ; for any Yasawar (Jaiswar) Kurmi who from poverty sells himself or his children is admitted among the Dhanuks. All the Dhanuks at one time were probably slaves, and many have been purchased to fill up the military ranks-a method of recruiting that has been long prevalent in Asia, the armies of the Parthians having been composed almost entirely of slaves; and the custom is still, I believe, pretty general among the Turks. A great many of the Dbanuks are still slaves, but some annually procure their liberty by the inability of their masters to maintain them, and by their unwillingness to sell their fellow-creatures." According to the Padma Purana quoted by Sir Henry Elliot, Dhanuks are descended from a ChamaI' and a female Chanda!. Another equally mythical pedigree makes the mother a ChamaI' and the father an outcast Ahir. Such statements, however slight their historical value, serve to indicate in a general way the social rank held by the Dhanuks at the time when it was first thought necessary to enrol them among the mixed castes. In this point of view the degraded parentage assigned to the caste lends some support to the conjecture that they may be an offshoot from one of the non-Aryan tribes.

Internal structure

Dhanuks are divided into the following sub-castes :-Chhilatia or Silhotia, Magahya, Tirhutia or Chiraut, Jaiswar, Kanauj ia, Khapariya, Dudhwar or Dojwar, Sunri-Dhanuk, and Kathautia. Sir Henry Elliot, writing of the Dbanuks of the North-West Provinces, gives a slightly different list, which will be found in Appendix 1. Buchanan mentions Jaiswar, Magabya, Dojwar, and Chhilatiya. Little is known regarding the origin of any of the sub-castes. Magahya, Tirhutia, Kanaujia, are common territorial names used by many castes to denote sub-castes who reside in, or are supposed to have emigrated from, particular tracts of country. The Dudlnvar or Dojwar sub-caste pride themselves upon not castrating bull-calves. The Sunri-Dhanuk are said to have been separated from the rest of the caste by reason of their taking service with members of the deslised Sunri and rl'eli castes. According to some authorities the Chhilatia sub-caste is also known bythename of J ai~war -Kurmi, a fact which to some extent bears out Buchanan's suggestion that there may be some connexion between the Dhanuk and Kurmi-castes. Speculations based upon resemblances of names are, however, apt to be misleading, and I can find no independent evidence to show that the Dhanuks are a branch of the Kurmis, or, which is equally possible, that the J aiswar sub¬caste of the Kurmis derive their origin from the Dhanuks. It is curious that the distinction between personal service and cultivation, which has led to the formation of sub-castes among the Gangota, Armlt, and Kewat, should not have produced the same effect in the case of the Dhanuks. Throughout Behar, indeed, full expression is given to these differences of occupation in the titles borne by those who follow the one or the other mode of life; but it is only in Purniah that they form an impassable barrier to iutermarriage between the Khawasia sub-caste, who are employed as domestic servants, and the Gharbait and Mandai, who confine themselves to agriculture. The sections of the caste are shown in Appendix 1. They are comparatively few in number, and their influence on marriage seems to be gradually dying out, its place boing taken by the more modern system of counting prohibited degrees. For this purpose the standard formula mamera, chacitera, etc., is in use, the prohibition extending to seven generations in the descending line.

Marriages

Both infant and adllit-marriage are recognised by the Dhanuk caste, but the former practice is deemed the more respectable, and all who can afford to do so endeavour to get their daughters married before they attain tho age of puberty. The marriage ceremony differs little from that in vogue among other Behar castes of similar social standing. In the matter of polygamy their custom seems to vary in different parts of the country. In Behar it is usually held that a man may not take a second wife unless the first is barren or suffers from an incumble disease; but in Purniah no such restrict.ions seem to exist, and a man may have as many wives as he can afford to maintain. A widow may marry again by the sagai or chumauna form, in which Brahmans take no part; and the union of the couple is completed by the bridegroom smearing red lead with his left hand on the forehead of the bride. In Purniah the deceased husband's younger brother or cousin, should such a relative exist, is considered to have a preferontial claim to marry the widow ; but elsewhere less stress is laid on this condition, and a widow is free to marry whom she pleases, provided that she does not infringe the prohibited degrees. Divorce is not recognised in Behar, but the Dhanuks of the Santal Parganas, following apparently the example of the aboriginal races, permit a husband to divorce an unchaste wife by making a formal declaration before the panchayat of his intention to cast her off, and tearing a leaf in two to symbolise and record the separation. The proceedings conclude with a feast to all the relations, the idea of which appears to be that by thus entertaining his family the husband frees himself from the stain of having lived with a disreputable woman. Women so divorced may marry again, provided that their favours have been bestowed solely on members of the caste. Indiscretions outside that circle are punished by immediate expulsion, and cannot be atoned for by any form of penance except in the unusual case of a Dhanuk woman living with a man of notably higher caste.

Religion

The Religion of the Dhanuks presents no features of special interest. They worship the regular Hindu gods, and employ as their priests Maithil Brahmans, who are received on equal terms by other members of the sacred order. Among their minor gods we find Bandi, Goraiya, Mahabu:, Ram Thakur, Gahil, Dharm Raj, and Sokha Sindabas. The last appears to be the spirit of some departed sorcerer. Dhanuks are also much given to the worship of the sun, to whom flowers, rice, betel-leaves, cloves, cardamoms, molasses, together with money and even clothes, are offered on Sundays during the months of Baisakh and Aghan. The offerings are taken by the caste Brahman or the Mali. The dead are burned, and the sradda ceremony is performed on the thirteenth day after death. In the case of persons who die from snake-bite, their relatives offer milk and fried rice (lawa) to snakes on the Nagpanchami day in the month of Srawan.

Social status and occupation

Notwithstanding the degraded parentage assigned to them by tradition, and the probability that they are really of non-Aryan descent, the social position of dhanuks at the present day quite respectable. They rank with Kurmis and Koiris, and Brahmans will take water from their hands. They themselves will eat cooked food, drink and smoke with the Kurmi, Amat, and Kewat; and Bahiot Dhanuks 'Yill eat the leavings of Brahmans, Rajputs, and Kayasths in whose houses they are employed. Personal service, including palan¬quin-bearing and agriculture, are their chief occupations, and in some parts of the country they are engaged in the cultivation of hemp and the manufacture of string, whence they derive the title Sankatwar. Most of them are ocuupancy or non-occupancy raiyats, and the poorer members of the caste earn their living as agricultural day-labourers.

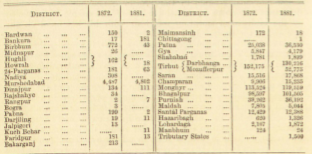

The following statement shows the number and distribution of Dhanuks in 1872 and 1881 :¬