Delhi: Azadpur Mandi

This is a collection of newspaper articles selected for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

AGROPOLIS

By Jayashree Nandi & Durgesh Nandan Jha | The Times of India 2013/05/12

Azadpur m a n d i is where the city gets all its vitamins from. Delhi’s fruit-and-vegetable port works round the clock, receiving and distributing millions of tonnes of fresh produce with methods that are arcane and seem maddening to the first-time visitor A burly man is calling o u t t o b i d d e r s : “112…112, anyone? Ok, 115…116?” It’s 6am at the Chaudhary Hira Singh Fruit and Vegetable Market, commonly known as Azadpur mandi, and the peas he is auctioning have just arrived from Shimla.

At another shed nearby, other commission agents (middlemen) are trying to get the ‘best price’ for safeda mangoes. They don’t bid loudly. Instead, they communicate with buyers in code, by touching hands under a handkerchief. This way, the price changes with every buyer. It’s an old-fashioned way, and illegal too, but that’s how most deals are struck at the mandi.

“There are many buyers who bid high but never pay on time. We follow this ‘underhand’ rule for auctioning to keep them away,” says Kanti Lal, an auctioneer.

Azadpur mandi feels out of date with the rest of the city but it still is the most important link in Delhi’s food chain, and its mammoth operations are absolutely awesome. Transactions worth hundreds of crores take place here every day. “It’s a round-the-clock mandi. Auctions and transactions take place even at night,” says Rajeev Bhatia, a thirdgeneration trader.

After an auction, a bill is prepared to calculate the payment due to farmers. “We deduct charges for labour and transport, and our commission before sending the net amount to farmers,” Bhatia says.

Thousands of local vendors gather at the mandi to buy produce from the middlemen. “Vendors have to come here to buy vegetables. Some also head to the Okhla and Ghazipur markets to buy produce but most come here at the crack of dawn to be able to sell in their areas early in the morning,” says Sunil Bhatia, who works with Rajiv.

The Bhatias have seen the market change in many ways down the years. They confirm what Delhiites always lament—vegetables are not as good as they used to be and many types are no longer available. “At least 12-13 trucks of peas used to arrive from a village near Shimla. Now, they grow fruit instead to earn more. A lot of people have dropped out of farming, which also reflects in the supplies here,” Sunil says.

Like the farmers, traders also seem to be losing interest in the business. “People are all for the mall culture and support FDI in retail. They don’t know it will end up raising prices further,” says a trader.

Handling and sorting the produce is labour-intense work and large numbers of labourers (palledar) are employed at the mandi. “The trader has to like the vegetables. They have to be shiny clean. My job is to select the better looking onions and put them in the sack. I also cook for the middlemen who work here. They pay me about Rs 3,000 for everything,” says Rajnikant, a native of Bihar. Life is harder for porters who carry gunny bags weighing 20-50kg and earn Rs 5-15 apiece.

A first visit to the mandi is an assault on the senses. It’s colourful because of the variety of produce it gets. Giant orange pumpkins from Kolkata occupy an entire stall; on the other side bright yellow lemons and tonnes of green herbs make a vibrant collage. Parts of the mandi smell putrid while others bear a sweet smell of fresh fruit and vegetables. Cows roam around the premises and dung is splattered even inside the sheds. Sludge from decomposed vegetable and fruit waste make it difficult to walk about.

In 2006, the Delhi government had announced plans to modernize the mandi but nothing came of it beyond the establishment of an office complex for the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) and a Kisan Bhavan for farmers and traders to stay in. APMC officials say the compost plant at Tikri Khampur which used to recycle the organic waste from Azadpur mandi has also been out of order for almost two years. There are plans to start another mandi at Tikri Khampur to lessen the crowd at Azadpur. “The new mandi is going to be very well equipped. We hope to modernize the auctions also…”, says an APMC official.

Until the new market is ready, Delhi will depend on this bustling trading hub and farmers will have to wait for a mandi that assures them a fair price.

NO TRANSPARENCY

Farmers bring their produce to commission agents, who auction it by calling out prices quoted by potential buyers around them. The commission agent checks with the farmer before handing over the produce to the highest bidder. If the deal goes through, the farmer pays 6% of the final rate to the commission agent. Sometimes, APMC staff is also present at the auction. Prices change through the day depending on the quality of the produce. But Azadpur m a n d i is infamous for its illegal auctions. There is no transparency in the sale of more expensive commodities like apples and mangoes: they are auctioned in code.

HEAVY WORK

The Azadpur m a n d i never sleeps or slows down. It is kept alive and active by the thousands of labourers, also known as p a ll e d a r s, who work in shifts. They live in godowns and offices. “The traders have allocated space within the offices and godowns for us to sleep. We get Rs 4 per sack for loading and unloading. There is one person in every group whose job is to cook food for the rest,” says Puran Chand, one of the p a ll e d a r s. Most labourers at the m a n d i are from UP and Bihar.

THE MARKET PEELED

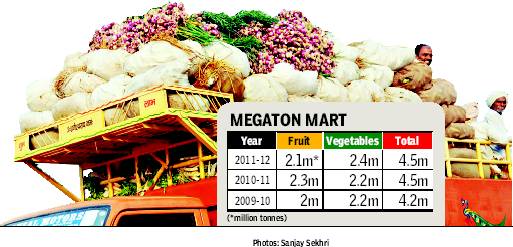

Azadpur m a n d i is Asia’s largest wholesale market for fruits and vegetables. Every day thousands of trucks bring fresh produce to it from all over the country, and the annual arrivals amount to millions of tonnes

PRICE SETTING |

APMC staff monitors the auctions in each shed and notes the final price for each commodity. It then lists the day’s ‘model rate’ for every commodity

REVENUE STREAM |

APMC runs on the market fee deposited by traders. It charges 1% of the sale value of every transaction. Last year it raised Rs 67 crore

Vital statistics

Area: 43.65 acres

6 nationalised banks in the mandi

18 fruit and vegetable sheds

7 cold stores

55 types of fruit

68 types of vegetables

A Kisan Bhawan (farmers’ house) for farmers to stay in

3,000 vehicles uploaded every day

2,200 licensed wholesale traders

600 employees of the Agricultural Produce Market Committee

Overcrowding

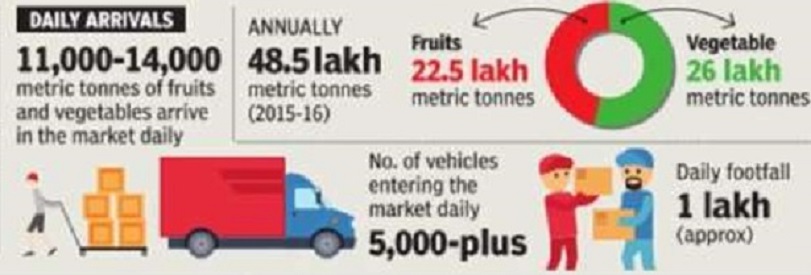

While the fruit and vegetable wholesale market is the capital's lifeline, it's not equipped to deal with a daily footfall of nearly a lakh

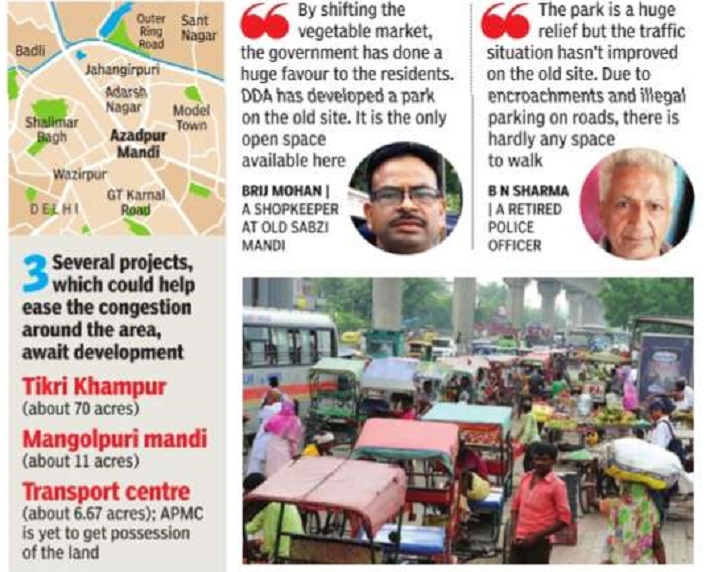

When the fruit and vegetable wholesale hub at Baraf Khana was shifted to Azadpur, around 7 km away , in 1975 in a bid to decongest Old Delhi, perhaps no one realised that the mart would outgrow its new site in just four decades. Today , the Chaudhary Hira Singh Wholesale Fruits and Vegetable Market, more popularly known as Azadpur mandi, has become an impossible place to operate out of.

Some 5,000 trucks and tempos enter the market every day to deliver up to 14,000 metric tonnes of fruits and vegetables. The roads are wide, but jammed through out the day . The sewerage system often gives up, especially in the monsoon season.Amenities like toilets and drinking water stations are grossly inadequate for the around one lakh people who work at and visit the market daily. “We have to buy drinking water,“ says Ram Das, a labour coordinator.

Business looks likely to rise as the city grows, but the market, declared to be of “national importance“ by the central government in 2004, is not in a position to take added pressure. The government had wisely envisaged a shift to Narela in 1997, having set aside 71 acres in Tikri Khampur near the Integrated Freight Complex, for Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC), which runs the mandi.

APMC officials say that tenders will “soon“ be floated to appoint a consultant to develop the project in Tikri Khampur. But this news does not enthuse the long-suffering wholesalers. “Does it take 20 years to plan a market?“ asks Bhatia. “The government probably wants to use the space to get commercial benefits rather than decongest Azadpur.“

Vijay Kumar, who lives near the wholesale centre, is exasperated by the traffic jams on the roads radiating from the market. “Trucks and encroachments by vendors on these roads create day-long congestion,“ he complains. A senior APMC official argues, “The market was designed four decades ago when the biggest truck was of six tyres.Today , we have 16-tyre trucks rolling in. There isn't sufficient space for these trucks.Loading and unloading at different spots and at different times also causes crowding.“

Though the APMC official says the “situation in the market is not so bad“, the truth is that merchants, urban planners and transport experts have long demanded decentralisation of the mandi. “Proposals have been placed before the managing committee for decongesting the market, but no action has been taken,“ rues Raj Kumar Bhatia, for mer member of APMC.

Transport experts say there is a need to carefully plan the new wholesale markets after taking into consideration the flow of goods. “If distribution centres are located on the outskirts, no truck need enter the city,“ points out Sewa Ram, associate professor, department of transport planning, School of Planning and Architecture. “So depending on the type of goods they bring in, the traders should be relocated to the nearest IFC.“

For instance, since 80% of apples from Himachal Pradesh and Kashmir is distributed from Azadpur, the traders had proposed that apple sellers be shifted to Tikri Khampur, which is suitably located on National Highway 1, says Bhatia. “The large space currently occupied by apple merchants would also have been freed up for use by others,“ he adds.

Residents at the erstwhile mandi at Baraf Khana have seen the changes that a shift can bring. DDA developed a 3,000-sq m park in place of the old market and widened the roads there. Admittedly , the streets are still overcrowded, but the park provides breathing space.

Porters

2018: Most porters are unofficial

From: Paras Singh, Asia’s biggest mandi has just two porters on paper, February 27, 2018: The Times of India

AZADPUR MANDI: Hundreds Protest, Demand Right To Identity

Three and a half decades ago, Jeetu Singh migrated to the national capital from Azamgarh in Uttar Pradesh to provide a good life for his family. Little did he know that he would end up doing backbreaking work, quite literally, without any identity in a thankless sector where dreams die a thousand deaths every day.

Since 1983, Singh has spent the better part of his life carrying 80-120kg gunny bags at Asia’s largest fruit and vegetable market, Azadpur mandi. Now, he is barely able to walk straight. Pointing at the metal rod in his broken leg, he said, “My aadhti (wholesale trader) refused to accept me as one of his workers when I got injured after a dozen sacks fell over me while unloading.”

The elderly palledar and over 50,000 workers like him are still not officially recognised as “porters” or “head-load workers” by Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC).

Surprisingly, an RTI query has revealed that only two porters have been issued “Gcategory licence” or badges in the market where 11,000-14,000 metric tonnes of fruits and vegetables arrive daily.

Hundreds of palledars organised a Satyagrah on Monday demanding their right to identity. Prakash Kumar, general secretary of Rashtriya Hamal Panchayat, said, “Delhi Agricultural Produce Marketing (Regulation) Act, 1998 clearly stipulates that it is duty of APMC to issue licences to traders, agents and other workers under A-G categories. While over 2,500 other licences are issued every year, porters have been singled out since the beginning. Nothing has happened even after several orders and assurances by CMs and the administration. Giving just two licences amounts to denying porters their rights.”

“We unload and load products from 50,000 vehicles that enter the market. One man carries up to 300 gunny bags weighing from 60-120kg daily. Carrying 18 tonnes a day is bound to take a toll on one’s health,” said Lal Bhadur Sahani (40), a palledar.

Accidents are also commonplace in the congested area where cows, porters and trucks jostle for space. “A few months ago, the market management refused to help a worker’s family after he got crushed by a truck. We collected donations for his cremation,” Sahani added.

The lack of an identity also denies the porters access to safeguards under many labour laws, compensation, healthcare and respite from harassment. “As we are unable to give proof that we work at the market, the cops beat us and demand money,” said Rajkumar Thakur, while unloading potatoes.

With 48.5lakh tonnes of produce being processed over the 79-acre area every year, accidents due to trucks and collapsing stacks of gunny bags happen every other week. “The only dispensary and mohalla clinic is closed half of the week. It doesn’t even have basic facilities for treatment in case of accidents,” complained Raju Gaud.

Many complained about being paid partially by adhatis in cash. Once they are regulated through licences, their salary would have to be deposited in bank accounts and they would no longer be harassed by cops.

The secretary of APMC, Rajesh Goyal, said that he had recently taken up office so wasn’t aware about why no licences were issued in the past decades. “I met the delegation of porters and assured them that the process to issue licences will start in 15 days,” he added.