Chitra Ganesh

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Chitra Ganesh

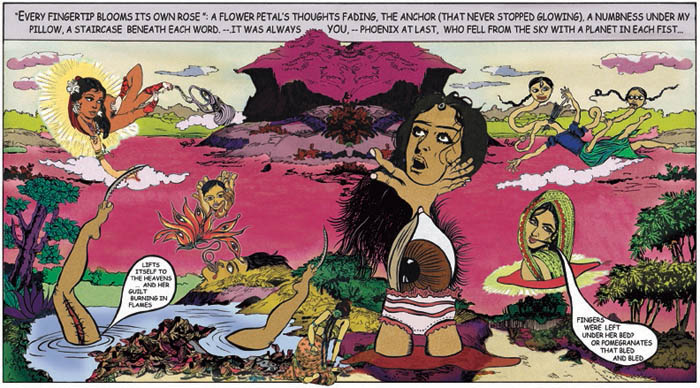

Brooklyn-based artist Chitra Ganesh, a 2012 Guggenheim fellow, has spent years riffing on the women in the ACK [Amar Chitra Katha: comic-book versions of the Indian classics as well as religious epics] series in her art. She collages her ink drawings with original ACK images that she manipulates on the computer, and rewrites the text (“What is the common denominator of these traumas?”) poignantly, to express the daily miseries with which Indian women live.

In her comic books “Tales from Amnesia” (2008) and “She: the Question…” (2012), women occupy the same epic settings but are disembodied, inflamed, three-breasted, half-naked, and headless or bloodied. “I wanted to touch on and maximize the kitsch or humor already in the form and to explore the femininity I noticed in ACK and other comics, where women are depicted relationally to men—as wives, daughters, or queens,” she said. “I wondered what it would be like to tell stories with women at the center, moving them from supporting roles to agents enacting their fantasies or conflicts.”

It’s the same question that India itself is facing today, still reeling from collective rage after the two brutal rape cases in Delhi and Bombay. How do you make women’s rights more central to India’s cultural identity, and how do you prevent violence by changing deep-rooted male ideas about women and sexuality? These comics are just one indicator of the cultural progress that India must make. One frame from Ganesh’s first comic book offers hope: “A series of successive illusions shattered the old country and swept it into the river,” it says.

Diane Mehta is a writer in Brooklyn.

The artist's own statement

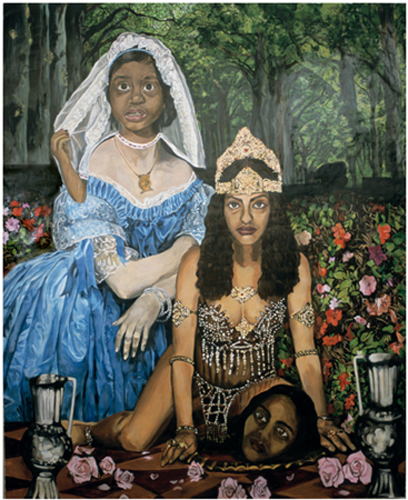

[[2]]

Based on images from the Bollywood film industry, anthropological, scientific, and police file photos, these works investigate social codes at work in mass media imaginings of South Asian culture. By highlighting the violence and performative artifice inherent in popular representations of gender and class,the works explore problematics of representation in the post-colonial era. These contradictions emerge in the paintings, where women are figured as both perpetrators and victims of violence; as simultaneously compliant and subversive. The Bollywood system itself is significant as a model of contradiction: although appearing to reflect certain structures of the Western Hollywood system, it has surpassed a mere colonial framework, becoming a vast and powerful institution with its own mythologies. Paintings exploit and dismantle these mythologies -- the restoration of feminine virtue by masculine authority, the necessity of heterosexual union, bound up with 'authentic' culture, and social reproduction, for narrative closure. Works expose how female sexuality is racialized, and how sexual codes are established by performance. I integrate anthropological, scientific, and film imagery to suggest that symbolic violence cuts across oppositional visual regimes, in that anthropology, as a scientific discourse, sees its goal as the elucidation of fact rather than fictive narrative. While the project creates space for narratives excluded from visual regimes maintained by National Geographic magazines or Hindi films, my intention is not ‘substituting a 'correct' ethnic image for an 'incorrect' one.’ The work doesn’t seek to recover an idealized model of female subjectivity. Rather, it intervenes into dominant visual systems, rubbing against the narrative grain by asking how images are constructed.