Cheruman

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Cheruman

The Cherumans or Cherumukkal have been defined as a Malayālam caste of agricultural serfs, and as members of an inferior caste in Malabar, who are, as a rule, toilers attached to the soil. In the Madras Census Report, 1891, it is stated that “this caste is called Cheruman in South Malabar and Pulayan [46]in North Malabar. Even in South Malabar where they are called Cheruman, a large sub-division numbering over 30,000 is called Pula Cheruman. The most important of the sub-divisions returned are Kanakkan, Pula Cheruman, Erālan, Kūdān and Rōlan. Kanakkan and Pula Cheruman are found in all the southern tāluks, Kūdān almost wholly in Walluvanād, and Erālan in Pālghat and Walluvanād.” In the Census Report, 1901, Ālan (slave), and Paramban are given as sub-castes of Cheruman. According to one version, the name Cheruma or Cheramakkal signifies sons of the soil; and, according to another, Cheriamakkal means little children, as Parasurāma directed that they should be cared for, and treated as such. The word Pulayan is said to be derived from pula, meaning pollution.

Of the Cherumans, the following account is given in the Gazetteer of Malabar. “They are said to be divided into 39 divisions, the more important of which are the Kanakka Cherumans, the Pula Cherumans or Pulayas, the Era Cherumans or Erālans, the Rōli Cherumans or Rōlans, and the Kūdāns. Whether these sub-divisions should be treated as separate castes or not, it is hardly possible to determine; some of them at least are endogamous groups, and some are still further sub-divided. Thus the Pulayas of Chirakkal are said to be divided into one endogamous and eleven exogamous groups, called Māvadan, Elamanām, Tacchakudiyan, Kundatōn, Cheruvulan, Mulattan, Tālan, Vannatam, Eramālōdiyan, Mullaviriyan, Egudan, and Kundōn. Some at least of these group names obviously denote differences of occupation.

The Kundōtti, or woman of the last group, acts as midwife; and in consequence the group is considered to convey pollution by touch to members of the other groups, and they will neither eat nor marry with those belonging to it. Death or birth pollution is removed by a member of the Māvadan class called Maruttan, who sprinkles cowdung mixed with water on the feet, and milk on the head of the person to be purified. At weddings, the Maruttan receives 32 fanams, the prescribed price of a bride, from the bridegroom, and gives it to the bride’s people. The Era Cherumans and Kanakkans, who are found only in the southern tāluks of the district, appear to be divided into exogamous groups called Kūttams, many of which seem to be named after the house-name of the masters whom they serve. The Cherumans are almost solely employed as agricultural labourers and coolies; but they also make mats and baskets.”

It is noted26 by Mr. L. K. Anantha Krishna Iyer that “from traditions current among the Pulayas, it would appear that, once upon a time, they had dominion over several parts of the country. A person called Aikkara Yajaman, whose ancestors were Pulaya kings, is still held in considerable respect by the Pulayas of North Travancore, and acknowledged as their chieftain and lord, while the Aikkaranād in the Kunnethnād tāluk still remains to lend colour to the tale. In Trivandrum, on the banks of the Velli lake, is a hill called Pulayanar Kotta, where it is believed that a Pulaya king once ruled. In other places, they are also said to have held sway. As a Paraya found at Melkota the image of Selvapillai, as a Savara was originally in possession of the sacred stone which became the idol in the temple of Jaganath, so also is the worship of Padmanābha at Trivandrum intimately connected with a Pulayan. Once a Pulaya [48]woman, who was living with her husband in the Ananthan kādu (jungle), suddenly heard the cry of a baby. She rushed to the spot, and saw to her surprise a child lying on the ground, protected by a snake.

She took pity on it, and nursed it like her own child. The appearance of the snake intimated to her the divine origin of the infant. This proved to be true, for the child was an incarnation of Vishnu. As soon as the Rāja of Travancore heard of the wonderful event, he built a shrine on the spot where the baby had been found, and dedicated it to Padmanābha. The Pulayas round Trivandrum assert to this day that, in former times, a Pulaya king ruled, and had his castle not far from the present capital of Travancore. The following story is also current among them. The Pulayas got from the god Siva a boon, with spade and axe, to clear forests, own lands, and cultivate them. When other people took possession of them, they were advised to work under them.”

According to Mr. Logan,27 the Cherumans are of two sections, one of which, the Iraya, are of slightly higher social standing than the Pulayan. “As the names denote, the former are permitted to come as far as the eaves (ira) of their employers’ houses, while the latter name denotes that they convey pollution to all whom they meet or approach.” The name Cheruman is supposed to be derived from cheru, small, the Cheruman being short of stature, or from chera, a dam or low-lying rice field. Mr. Logan, however, was of opinion that there is ample evidence that “the Malabar coast at one time constituted the kingdom or Empire of Chēra, and the nād or county of Chēranād lying on the coast and inland south-east of Calicut remains to the present day [49]to give a local habitation to the ancient name. Moreover, the name of the great Emperor of Malabar, who is known to every child on the coast as Chēramān Perumal, was undoubtedly the title and not the name of the Emperor, and meant the chief (literally, big man) of the Chēra people.”

Of the history of slavery in Malabar an admirable account is given by Mr. Logan, from which the following extracts are taken. “In 1792, the year in which British rule commenced, a proclamation was issued against dealing in slaves. In 1819, the principal Collector wrote a report on the condition of the Cherumar, and received orders that the practice of selling slaves for arrears of revenue be immediately discontinued.

In 1821, the Court of Directors expressed considerable dissatisfaction at the lack of precise information which had been vouchsafed to them, and said ‘We are told that part of the cultivators are held as slaves: that they are attached to the soil, and marketable property.’ In 1836, the Government ordered the remission in the Collector’s accounts of Rs. 927–13–0, which was the annual revenue from slaves on the Government lands in Malabar, and the Government was at the same time ‘pleased to accede to the recommendation in favour of emancipating the slaves on the Government lands in Malabar.’ In 1841, Mr. E. B. Thomas, the Judge at Calicut, wrote in strong terms a letter to the Sadr Adālat, in which he pointed out that women in some tāluks (divisions) fetched higher prices, in order to breed slaves; that the average cost of a young male under ten years was about Rs. 3–8–0, of a female somewhat less; that an infant ten months old was sold in a court auction for Rs. 1–10–6 independent of the price of its mother; and that, in a recent suit, the right to twenty-seven slaves [50]was the ‘sole matter of litigation, and was disposed of on its merits.’ In a further letter, Mr. Thomas pointed out that the slaves had increased in numbers from 144,000 at the Census, 1835, to 159,000 at the Census, 1842.

It was apparently these letters which decided the Board of Directors to send out orders to legislate. And the Government of India passed Act V of 1843, of which the provisions were widely published through Malabar. The Collector explained to the Cherumar that it was in their interest, as well as their duty, to remain with their masters, if kindly treated. He proclaimed that ‘the Government will not order a slave who is in the employ of an individual to forsake him and go to the service of another claimant; nor will the Government interfere with the slave’s inclination as to where he wishes to work.’ And again, ‘Any person claiming a slave as janmam, kānam or panayam, the right of such claim or claims will not be investigated into at any one of the public offices or courts.’ In 1852, and again in 1855, the fact that traffic in slaves still continued was brought to the notice of Government, but on full consideration no further measures for the emancipation of the Cherumar were deemed to be necessary.

The Cherumar even yet have not realised what public opinion in England would probably have forced down their throats fifty years ago, and there is reason to think that they are still, even now, with their full consent bought and sold and hired out, although, of course, the transaction must be kept secret for fear of the penalties of the Penal Code, which came into force in 1862, and was the real final blow at slavery in India. The slaves, however, as a caste will never understand what real freedom means, until measures are adopted to give them indefeasible rights in the small orchards occupied by them as house-sites.” It is noted by [51]Mr. Anantha Krishna Iyer that “though slavery has been abolished many years ago, the name valliyal (a person receiving valli, i.e., paddy given to a slave) still survives.” By the Penal Code it is enacted that— Whoever imports, exports, removes, buys, sells, or disposes of any person as a slave, or accepts, receives, or detains against his will any person as a slave, shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to seven years, and shall also be liable to a fine.

Whoever habitually imports, exports, removes, buys, sells, traffics or deals in slaves, shall be punished with transportation for life, or with imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years, and shall be liable to a fine. Whoever unlawfully compels any person to labour against the will of that person, shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to one year, or with a fine, or with both. “Very low indeed,” Mr. S. Appadorai Iyer writes,28 “is the social position of these miserable beings. When a Cherumar meets a person of superior caste; he must stand at a distance of thirty feet. If he comes within this prohibited distance, his approach is said to cause pollution, which is removed only by bathing in water. A Cherumar cannot approach a Brāhman village or temple, or tank. If he does so, purification becomes necessary. Even while using the public road, if he sees his lord and master, he has to leave the ordinary way and walk, it may be in the mud, to avoid his displeasure by accidentally polluting him.

To avoid polluting the passer-by, he repeats the unpleasant sound ‘O, oh, O—’. [In some places, e.g., Palghāt, one may often see a Cheruman with a dirty piece of cloth spread [52]on the roadside, and yelling in a shrill voice ‘Ambrāne, Ambarāne, give me some pice, and throw them on the cloth.’] His position is intolerable in the Native States of Cochin and Travancore, where Brāhman influence is in the ascendant; while in the Palghāt tāluk the Cherumars cannot, even to this day, enter the bazaar.” A melancholy picture has been drawn of the Cherumans tramping along the marshes in mud, often wet up to their waists, to avoid polluting their superiors. In 1904, a Cheruman came within polluting distance of a Nāyar, and was struck with a stick. The Cheruman went off and fetched another, whereupon the Nāyar ran away. He was, however, pursued by the Cherumans. In defending himself with a spade, the Nāyar struck the foremost Cheruman on the head, and killed him.29 In another case, a Cheruman, who was the servant of a Māppilla, was fetching grass for his master, when he inadvertently approached some Tiyans, and thereby polluted them. The indignant Tiyans gave not only the Cheruman, but his master also, a sound beating by way of avenging the insult offered to them.

The status of the Pulayas of the Cochin State is thus described by Mr. Anantha Krishna Iyer. “They abstain from eating food prepared by the Velakkathalavans (barbers), Mannans (washermen), Pānāns, Vettuvans, Parayans, Nayādis, Ulladans, Malayans, and Kādars. The Pulayas in the southern parts of the State have to stand at a distance of 90 feet from Brāhmans and 64 feet from Nāyars, and this distance gradually diminishes towards the lower castes. They are polluted by Pula Cherumas, Parayas, Nayādis, and Ulladans. [The Pula Cherumas are said to eat beef, and sell the [53]hides of cattle.] The Kanakka Cherumas of the Chittūr tāluk pollute Era Cherumas and Konga Cherumas by touch, and by approach within a distance of seven or eight feet, and are themselves polluted by Pula Cherumas, Parayas, and Vettuvans, who have to stand at the same distance. Pulayas and Vettuvans bathe when they approach one another, for their status is a point of dispute as to which is superior to the other. When defiled by the touch of a Nayādi, a Cheruman has to bathe in seven tanks, and let a few drops of blood flow from one of his fingers.

A Brāhman who enters the compound of a Pulayan has to change his holy thread, and take panchagavyam (the five products of the cow) so as to be purified from pollution. The Valluva Pulayan of the Trichūr tāluk fasts for three days, if he happens to touch a cow that has been delivered of a calf. He lives on toddy and tender cocoanuts. He has also to fast three days after the delivery of his wife.” In ordinary conversation in Malabar, such expressions as Tiya-pād or Cheruma-pād (that is, the distance at which a Tiyan or Cheruman has to keep) are said to be commonly used.30 By Mr. T. K. Gopal Panikkar the Cherumans are described31 as “a very inferior race, who are regarded merely as agricultural instruments in the hands of the landlords their masters, who supply them with houses on their estates.

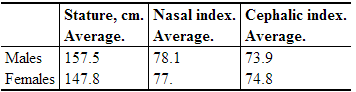

Their daily maintenance is supplied to them by their masters themselves. Every morning the master’s agent summons them to his house, and takes them away to work in the fields, in ploughing, drawing water from wells, and in short doing the whole of the cultivation. In the evening a certain quantity of paddy [54](unhusked rice) is distributed to them as wages. Both theory and practice, in the great majority of cases, are that they are fed at the master’s cost the whole year round, whether they work in the fields or not. But it is very seldom that they can have a holiday, regard being had to the nature of agriculture in Malabar.

It is the Cheruma that should plough the land, sow the seed, transplant the seedlings, regulate the flow of water in the fields, uproot the weeds, and see that the crops are not destroyed by animals, or stolen. When the crops ripen, he has to keep watch at night. The sentry house consists of a small oval-shaped portable roof, constructed of palmyra and cocoanut leaves, supported by four posts, across which are tied bamboos, which form the watchman’s bed. Wives sometimes accompany their husbands in their watches. When the harvest season approaches, the Cheruman’s hands are full. He has to cut the crops, carry them to the barn (kalam), separate the corn from the stalk, and winnow it.

The second crop operations immediately follow, and the Cheruma has to go through all these processes again. It is in the summer season that his work is light, when he is set to prepare vegetable gardens, or some odd job is found for him by his master. The old, infirm, and the children look after their master’s cattle. Receiving his daily pittance of paddy, the Cheruman enters his hut, and reserves a portion of it for the purchase of salt, chillies, toddy, tobacco, and dried fish. The other portion is reserved for food. The Cheruman spends the greater part of his wages on toddy.

It is a very common sight in Malabar to see a group of Cherumans, including women and children, sitting in front of a toddy shop, the Cheruman transferring the unfinished portion of the toddy to his wife, and the latter to the children. A Cheruman, [55]however, rarely gets intoxicated, or commits crime. No recess is allowed to the Cherumans, except on national holidays and celebrated temple festivals observed in honour of the goddess Bhagavati or Kāli, when they are quite free to indulge in drink. On these days, their hire is given in advance. With this they get intoxicated, and go to the poora-paramba or temple premises, where the festival is celebrated, in batches of four, each one tying his hands to another’s neck, and reciting every two seconds the peculiar sound:

“The Pulayans receive, in return for watching, a small portion of the field near the watchman’s rest-hut, which is left unreaped for him. It fetches him a para of paddy. “The Cherumas who are engaged in reaping get two bundles of corn each for every field. For measuring the corn from the farmyard, a Cheruman gets an edangazhy of paddy, in addition to his daily wage. Three paras of paddy are set apart for the local village deity. During the month of Karkadakam, the masters give every Cheruman a fowl, some oil, garlic, mustard, anise seeds, pepper, and turmeric. They prepare a decoction of seeds, and boil the flesh of the fowl in it, which they take for three days, during which they are allowed to take rest. Three days’ wages are also given in advance.”

In Travancore, a festival named Macam is held, of which the following account has been published. “The Macam (tenth constellation Regulus, which follows Thiru Onam in August), is regarded by Hindus as a day of great festivity. One must enjoy it even at the cost of one’s children, so runs an adage. The day is considered to be so lucky that a girl born under the star Regulus is verily born with a silver spoon in her mouth. It was on Macam, some say, that the Dēvas, to free themselves from the curse they were put under by a certain sage, had to churn the sea of milk to procure ambrosia. Be the cause which led to the celebration what it may, the Hindus of the present day have ever been enthusiastic in its observance; only some of the rude customs connected with it have died out in the course of time, or were put a stop to by Government. Sham fights were, and are still, in some places a feature of the day.

Such ]a sham fight used to be carried on at Pallam until, about a hundred years ago, it was stopped through the intervention of Colonel Munro, the British Resident in Travancore. The place is still called Patanilam (battle field), and the tank, on opposite sides of which the contending parties assembled, Chorakulam (pool of blood). The steel swords and spears, of curious and various shapes, and shields large enough to cover a man, are even now preserved in the local temple. Many lives were lost in these fights. It is not generally known, even to people in these parts, that a sham fight takes place on Macam and the previous day every year at a place called Wezhapra, between the Changanacherry and Ambalapuzha taluks. Three banyan trees mark the place.

People, especially Pulayas and Pariahs, to the number of many thousands, collect round the outside trees with steel swords, spears, and slings in their hands. A small bund (embankment) separates the two parties. They have to perform certain religious rites near the tree which stands in the middle, and, in doing so, make some movements with their swords and spears to the accompaniment of music. If those standing on one side of the bund cross it, a regular fight is the result. In order to avoid such things, without at the same time interfering with their liberty to worship at the spot, the Government this year made all the necessary arrangements. The Police were sent for the purpose. Everything went off smoothly but for one untoward event. The people had been told not to come armed with steel weapons, but with wooden ones. They had to put them down, and were then allowed to go and worship.”

Of conversion to Muhammadanism at the present time, a good example is afforded by the Cherumans. “This caste,” the Census Superintendent, 1881, writes, numbered 99,009 in Malabar at the census of 1871, and, in 1881, is returned as only 64,735. There are 40,000 fewer Cherumans than there would have been but for some disturbing influence, and this is very well known to be conversion to Muhammadanism. The honour of Islam once conferred on the Cheruman, he moves at one spring several places higher than that which he originally occupied.” “Conversion to Muhammadanism,” Mr. Logan writes, “has had a marked effect in freeing the slave caste in Malabar from their former burthens. By conversion a Cheruman obtains a distinct rise in the social scale, and, if he is in consequence bullied or beaten, the influence of the whole Muhammadan community comes to his aid.” It has been noted that Cheruman converts to Islam take part in the Moplah (Māppilla) outbreaks, which from time to time disturb the peace of Malabar.

The home of the Cheruman is called a chāla or hut, which has a thatched roof of grass and palm-leaves resembling an immense bee-hive. A big underground cell, with a ceiling of planks, forms the granary of the occupants of these huts. The chief house furniture consists of a pestle and mortar, and two or three earthenware pots.

The habitations of the Pulayas of Cochin are thus described by Mr. Anantha Krishna Iyer. “Their huts are generally called madams, which are put up on the banks of fields, in the middle of rice flats, or on trees along their borders, so as to enable them to watch the crops after the toils of the day. They are discouraged from erecting better huts, under the idea that, if settled more comfortably, they would be less inclined to move as cultivation required. The madams are very poor huts, supported on four small posts, and thatched with leaves. The sides are protected with the same kind of leaves. There is only one room, and the floor, though slightly raised, is very damp during the rainy months. These temporary buildings are removed after the harvest, and put up in places where cultivation has to be carried on. All the members of the family sleep together in the same hut. Small temporary huts are sometimes erected, which are little better than inverted baskets.

These are placed in the rice field while the crop is on the ground, and near the stacks while it is being thrashed. In the northern parts of the State, the Pulaya huts are made of mud walls, and provided with wooden doors. The roofs are of bamboo framework thatched with palmyra palm leaves. The floor is raised, and the huts are provided with pyals (raised platforms) on three sides. They have also small compounds (grounds) around them. There is only one room inside, which is the sleeping apartment of the newly married youngsters. The others, I am told, sleep on the verandahs. The utensils consist of a few earthen pots for cooking and keeping water, and a few earthen dishes for taking food. In addition to these, I found a wooden mortar, a few pestles, two pans, two winnowing pans, a fish basket for each woman, a few cocoanut shells for keeping salt and other things, a few baskets of their own making, in one of which a few dirty cloths were placed, some mats of their own making, a bamboo vessel for measuring corn, and a vessel for containing toddy.” “During the rainy season, the Cherumas in the field wear a few green leaves, especially those of the plantain tree, tied round their waists, and a small cone-shaped cap, made of plantain leaf, is worn on the head. This practice, among the females, has fallen into disuse in Malabar, though it is to some extent still found in the Native States.

The Cherumi is provided with one long piece of thick cloth, which she wraps round her waist, and which does not even reach the knees. She does not cover the chest.” The Cheruma females have been described as wearing, when at work in the open, a big oval-shaped handleless umbrella covered with palm leaves, which they place on their back, and which covers the whole of their person in the stooping attitude. The men use, during the rainy season, a short-handled palm-leaf umbrella.

The women are profusely decorated with cheap jewelry of which the following are examples:

1. Lobes of both ears widely dilated by rolled leaden ornaments. Brass, and two glass bead necklets, string necklet with flat brass ornaments, the size of a Venetian sequin, with device as in old Travancore gold coins, with two brass cylinders pendent behind, and tassels of red cotton. Three brass rings on right little finger; two on left ring finger, one brass and two steel bangles on left wrist.

2. Several bead necklets, and a single necklet of many rows of beads. Brass necklet like preceding, with steel prong and scoop, for removing wax from the ears and picking teeth, tied to one of the necklets. Attached to, and pendent from one necklet, three palm leaf rolls with symbols and Malayālam inscription to act as a charm in driving away devils. Three ornamental brass bangles on right forearm, two on left. Iron bangle on left wrist. Thin brass ring in helix of each ear. Seventy thin brass rings (alandōti) with heavy brass ornament (adikaya) in dilated lobe of each ear.

3. In addition to glass bead necklets, a necklet with heavy heart-shaped brass pendants. String round neck to ward off fever.

4. String necklet with five brass cylinders pendent; five brass bangles on right wrist; six brass and two iron bangles on left wrist.

Right hand, one copper and five brass rings on middle finger; one iron and three brass rings on little finger. Left hand, one copper and five brass rings on middle finger; three brass and two copper rings on ring finger; one brass ring on little finger. 5. Trouser button in helix of left ear.

6. Brass bead necklet with pendent brass ornament with legend “Best superior umbrella made in Japan, made for Fazalbhoy Peeroo Mahomed, Bombay.”

A Cheruman, at Calicut, had his hair long and unkempt, as he played the drum at the temple. Another had the hair arranged in four matted plaits, for the cure of disease in performance of a vow. A man who wore a copper cylinder on his loin string, containing a brass strip with mantrams (consecrated formulæ) engraved on it, sold it to me for a rupee with the assurance that it would protect me from devils.

Concerning the marriage ceremony of the Cherumans in Malabar, Mr. Appadorai Iyer writes that “the bridegroom’s sister is the chief performer. It is she who pays the bride’s price, and carries her off. The consent of the parents is required, and is signified by an interchange of visits between the parents of the bride and bridegroom. During these visits, rice-water (conji) is sipped. Before tasting the conji, they drop a fanam (local coin) into the vessel containing it, as a token of assent to the marriage. When the wedding party sets out, a large congregation of Cherumans follow, and at intervals indulge in stick play, the women singing in chorus to encourage them ‘Let us see, let us see the stick play (vadi tallu), Oh! Cheruman.’ The men and women mingle indiscriminately in the dance during the wedding ceremony. On the return to the bridegroom’s hut, the bride is expected to weep loudly, and deplore her fate. On entering the bridegroom’s hut, she must tread on a pestle placed across the threshold.”

During the dance, the women have been described as letting down their hair, and dancing with a tolerable amount of rhythmic precision amid vigorous drumming and singing. According to another account, the bridegroom receives from his brother-in-law a kerchief, which the giver ties round his waist, and a bangle which is placed on his arm. The bride receives a pewter vessel from her brother. Next her cousin ties a kerchief round the groom’s forehead, and sticks a betel leaf in it. The bride is then handed over to the bridegroom.

Of the puberty and marriage ceremonies of the Pulayas of Cochin, the following detailed account is given by Mr. Anantha Krishna Iyer. “When a Pulaya girl comes of age, she is located in a separate hut. Five Vallons (headmen), and the castemen of the kara (settlement), are invited to take part in the performance of the ceremony. A song, called malapattu, is sung for an hour by a Parayan to the accompaniment of drum and pipe. The Parayan gets a para of paddy, and his assistants three annas each. As soon as this is over, seven cocoanuts are broken, and the water thereof is poured over the head of the girl, and the broken halves are distributed among the five Vallons and seven girls who are also invited to be present. Some more water is also poured on the girl’s head at the time. She is lodged in a temporary hut for seven days, during which food is served to her at a distance. She is forbidden to go out and play with her friends. On the morning of the seventh day, the Vallons of the kara and the castemen are again invited. The latter bring with them some rice, vegetables, and toddy, to defray the expenses of the feast.

At dawn, the mother of the girl gives oil to the seven Pulaya maidens, and to her daughter for an oil-bath. They then go to a neighbouring tank (pond) or stream to bathe, and return home. The girl is then neatly dressed, and adorned in her best. Her face is painted yellow, and marked with spots of various colours. She stands before a few Parayas, who play on their flute and drum, to cast out the demons, if any, from her body. The girl leaps with frantic movements, if she is possessed by them. In that case, they transfer them to a tree close by driving a nail into the trunk after due offerings. If she is not possessed, she remains unmoved, and the Parayas bring the music to a close. The girl is again bathed with her companions, who are all treated to a dinner. The ceremony then comes to an end with a feast to the castemen. The ceremony described is performed by the Valluva Pulayas in the southern parts, near and around the suburbs of Cochin, but is unknown among other sub-tribes elsewhere. The devil-driving by the Parayas is not attended to. Nor is a temporary hut erected for the girl to be lodged in. She is allowed to remain in a corner of the hut, but is not permitted to touch others. She is bathed on the seventh day, and the castemen, friends and relations, are invited to a feast.

“Marriage is prohibited among members of the same koottam (family group). In the Chittūr tāluk, members of the same village do not intermarry, for they believe ]that their ancestors may have been the slaves of some local landlord, and, as such, the descendants of the same parents.

A young man may marry among the relations of his father, but not among those of his mother. In the Palghat tāluk, the Kanakka Cherumas pride themselves on the fact that they avoid girls within seven degrees of relationship. The marriage customs vary according to the sub-division. In the southern parts of the State, Pulaya girls are married before puberty, while in other places, among the Kanakka Cherumas and other sub-tribes, they are married both before and after puberty. In the former case, when a girl has not been married before puberty, she is regarded as having become polluted, and stigmatised as a woman whose age is known. Her parents and uncles lose all claim upon her. They formally drive her out of the hut, and proceed to purify it by sprinkling water mixed with cow-dung both inside and outside, and also with sand. She is thus turned out of caste. She was, in former times, handed over to the Vallon, who either married her to his own son, or sold her to a slave master. If a girl is too poor to be married before puberty, the castemen of the kara raise a subscription, and marry her to one of themselves.

“When a young Pulayan wishes to marry, he applies to his master, who is bound to defray the expenses. He gives seven fanams to the bride’s master, one fanam worth of cloth to the bride-elect, and about ten fanams for the marriage feast. In all, his expenses amount to ten rupees. The ceremony consists in tying a ring attached to a thread round the neck of the bride. This is provided by her parents. When he becomes tired of his wife, he may dispose of her to any other person who will pay the expenses incurred at the marriage. There are even now places where husband and wife serve different masters, but more frequently they serve the same master. The eldest male child belongs to the master of the mother. The rest of the family remain with the mother while young, but, being the property of the owner, revert to him when of an age to be useful. She also follows them, in the event of her becoming a widow. In some places, a man brings a woman to his master, and says that he wishes to keep her as his wife. She receives her allowance of rice, but may leave her husband as she likes, and is not particular in changing one spouse for another. In other places, the marriage ceremonies of the Era Cherumas are more formal.

The bridegroom’s party goes to the bride’s hut, and presents rice and betel leaf to the head of the family, and asks for the bride. Consent is indicated by the bride’s brother placing some rice and cloth before the assembly, and throwing rice on the headman of the caste, who is present. On the appointed day, the bridegroom goes to the hut with two companions, and presents the girl with cloth and twelve fanams. From that day he is regarded as her husband, and cohabitation begins at once. But the bride cannot accompany him until the ceremony called mangalam is performed. The bridegroom’s party goes in procession to the bride’s hut, where a feast awaits them. The man gives sweetmeats to the girl’s brother. The caste priest recites the family history of the two persons, and the names of their masters and deities.

They are then seated before a lamp and a heap of rice in a pandal (booth). One of the assembly gets up, and delivers a speech on the duties of married life, touching on the evils of theft, cheating, adultery, and so forth. Rice is thrown on the heads of the couple, and the man prostrates himself at the feet of the elders. Next day, rice is again thrown on their heads. Then the party assembled makes presents to the pair, a part of which goes to the priest, and a part to the master of the husband. Divorce is very easy, but the money paid must be returned to the woman. “In the Ooragam proverthy of the Trichūr tāluk, I find that the marriage among the Pulayas of that locality and the neighbouring villages is a rude form of sambandham (alliance), somewhat similar to that which prevails among the Nāyars, whose slaves a large majority of them are. The husband, if he may be so called, goes to the woman’s hut with his wages, to stay therein with her for the night. They may serve under different masters. A somewhat similar custom prevails among the Pula Cherumas of the Trichūr tāluk. The connection is called Merungu Kooduka, which means to tame, or to associate with.

“A young man, who wishes to marry, goes to the parents of the young woman, and asks their consent to associate with their daughter. If they approve, he goes to her at night as often as he likes. The woman seldom comes to the husband’s hut to stay with him, except with the permission of the thamar (landlord) on auspicious occasions. They are at liberty to separate at their will and pleasure, and the children born of the union belong to the mother’s landlord. Among the Kanakka Cherumas in the northern parts of the State, the following marital relations are in force. When a young man chooses a girl, the preliminary arrangements are made in her hut, in the presence of her parents, relations, and the castemen of the village. The auspicious day is fixed, and a sum of five fanams is paid as the bride’s price. The members assembled are treated to a dinner.

A similar entertainment is held at the bridegroom’s hut to the bride’s parents, uncles, and others who come to see the bridegroom. On the morning of the day fixed for the wedding, the bridegroom and his party go to the bride’s hut, where they are welcomed, and seated on mats in a small pandal put up in front of the hut. A muri (piece of cloth), and two small mundus (cloths) are the marriage presents to the bride. A vessel full of paddy (unhusked rice), a lighted lamp, and a cocoanut are placed in a conspicuous place therein. The bride is taken to the booth, and seated by the side of the bridegroom. Before she enters it, she goes seven times round it, with seven virgins before her. With prayers to their gods for blessings on the couple, the tāli (marriage badge) is tied round the bride’s neck. The bridegroom’s sister completes the knot. By a strange custom, the bride’s mother does not approach the bridegroom, lest it should cause a ceremonial pollution. The ceremony is brought to a close with a feast to those assembled. Toddy is an indispensable item of the feast. During the night, they amuse themselves by dancing a kind of wild dance, in which both men and women joyfully take part. After this, the bridegroom goes along to his own hut, along with his wife and his party, where also they indulge in a feast. After a week, two persons from the bride’s hut come to invite the married couple. The bride and bridegroom stay at the bride’s hut for a few days, and cannot return to his hut unless an entertainment, called Vathal Choru, is given him.

“The marriage customs of the Valluva Pulayas in the southern parts of the State, especially in the Cochin and Kanayannūr tāluks, are more formal. The average age of a young man for marriage is between fifteen and twenty, while that of a girl is between ten and twelve. Before a young Pulayan thinks of marriage, he has to contract a formal and voluntary friendship with another young Pulayan of the same age and locality. If he is not sociably inclined, his father selects one for him from a Pulaya of the same or higher status, but not of the same illam (family group).

If the two parents agree among themselves, they meet in the hut of either of them to solemnise it. They fix a day for the ceremony, and invite their Vallon and the castemen of the village. The guests are treated to a feast in the usual Pulaya fashion. The chief guest and the host eat together from the same dish. After the feast, the father of the boy, who has to obtain a friend for his son, enquires of the Vallon and those assembled whether he may be permitted to buy friendship by the payment of money. They give their permission, and the boy’s father gives the money to the father of the selected friend. The two boys then clasp hands, and they are never to quarrel. The new friend becomes from that time a member of the boy’s family. He comes in, and goes out of their hut as he likes.

There is no ceremony performed at it, or anything done without consulting him. He is thus an inseparable factor in all ceremonies, especially in marriages. I suspect that the friend has some claims on a man’s wife. The first observance in marriage consists in seeing the girl. The bridegroom-elect, his friend, father and maternal uncle, go to the bride’s hut, to be satisfied with the girl. If the wedding is not to take place at an early date, the bridegroom’s parents have to keep up the claim on the bride-elect by sending presents to her guardians. The presents, which are generally sweetmeats, are taken to her hut by the bridegroom and his friends, who are well fed by the mother of the girl, and are given a few necessaries when they take leave of her the next morning.

The next observance is the marriage negotiation, which consists in giving the bride’s price, and choosing an auspicious day in consultation with the local astrologer (Kaniyan). On the evening previous to the wedding, the friends and relations of the bridegroom are treated to a feast in his hut. Next day at dawn, the bridegroom and his friend, purified by a bath, and neatly dressed in a white cloth with a handkerchief tied over it, and with a knife stuck in their girdles, go to the hut of the bride-elect accompanied by his party, and are all well received, and seated on mats spread on the floor. Over a mat specially made by the bride’s mother are placed three measures of rice, some particles of gold, a brass plate, and a plank with a white and red cover on it.

The bridegroom, after going seven times round the pandal, stands on the plank, and the bride soon follows making three rounds, when four women hold a cloth canopy over her head, and seven virgins go in front of her. The bride then stands by the side of the bridegroom, and they face each other. Her guardian puts on the wedding necklace a gold bead on a string. Music is played, and prayers are offered up to the sun to bless the necklace which is tied round the neck of the girl. The bridegroom’s friend, standing behind, tightens the knot already made. The religious part of the ceremony is now over, and the bridegroom and bride are taken inside the hut, and food is served to them on the same leaf. Next the guests are fed, and then they begin the poli or subscription. A piece of silk, or any red cloth, is spread on the floor, or a brass plate is placed before the husband.

The guests assembled put in a few annas, and take leave of the chief host as they depart. The bride is soon taken to the bridegroom’s hut, and her parents visit her the next day, and get a consideration in return. On the fourth day, the bridegroom and bride bathe and worship the local deity, and, on the seventh day, they return to the bride’s hut, where the tāli (marriage badge) is formally removed from the neck of the girl, who is bedecked with brass beads round her neck, rings on her ears, and armlets. The next morning, the mother-in-law presents her son-in-law and his friend with a few necessaries of life, and sends them home with her daughter.

“During the seventh month of pregnancy, the ceremony of puli kuti, or tamarind juice drinking, is performed as among other castes. This is also an occasion for casting out devils, if any, from the body. The pregnant woman is brought back to the hut of her own family. The devil-driver erects a tent-like structure, and covers it with plantain bark and leaves of the cocoanut palm. The flower of an areca palm is fixed at the apex. A cocoanut palm flower is cut out and covered with a piece of cloth, the cut portion being exposed. The woman is seated in front of the tent-like structure with the flower, which symbolises the yet unborn child in the womb, in her lap. The water of a tender cocoanut in spoons made of the leaf of the jack tree (Artocarpus integrifolia) is poured over the cut end by the Vallon, guardian, and brothers and sisters present. The devil-driver then breaks open the flower, and, by looking at the fruits, predicts the sex of the child. If there are fruits at the end nearest the stem, the child will live and, if the number of fruits is even, there will be twins. There will be deaths if any fruit is not well formed.

The devil-driver repeats an incantation, whereby he invokes the aid of Kali, who is believed to be present in the tent. He fans the woman with the flower, and she throws rice and a flower on it. He repeats another incantation, which is a prayer to Kali to cast out the devil from her body. This magical ceremony is called Garbha Bali (pregnancy offering). The structure, with the offering, is taken up, and placed in a corner of the compound reserved for gods. The devotee then goes through the remaining forms of the ceremony. She pours into twenty-one leaf spoons placed in front of the tent a mixture of cow’s milk, water of the tender cocoanut, flower, and turmeric powder. Then she walks round the tent seven times, and sprinkles the mixture on it with a palm flower. Next she throws a handful of rice and paddy, after revolving each handful round her head, and then covers the offering with a piece of cloth. She now returns, and her husband puts into her mouth seven globules of prepared tamarind. The devil-driver rubs her body with Phlomis (?) petals and paddy, and thereby finds out whether she is possessed or not. If she is, the devil is driven out with the usual offerings. The devil-driver gets for his services twelve measures and a half of paddy, and two pieces of cloth. The husband should not, during this period, get shaved.

“When a young woman is about to give birth to a child, she is lodged in a small hut near her dwelling, and is attended by her mother and a few elderly women of the family. After the child is born, the mother and the baby are bathed. The woman is purified by a bath on the seventh day. The woman who has acted as midwife draws seven lines on the ground at intervals of two feet from one another, and spreads over them aloe leaves torn to shreds. Then, with burning sticks in the hand, the mother with the baby goes seven times over the leaves backwards and forwards, and is purified. For these seven days, the father should not eat anything made of rice. He lives on toddy, fruits, and other things.

The mother remains with her baby in the hut for sixteen days, when she is purified by a bath so as to be free from pollution, after which she goes to the main hut. Her enangathi (relation by marriage) sweeps the hut and compound, and sprinkles water mixed with cow-dung on her body as she returns after the bath. In some places, the bark of athi (Ficus glomerata) and ithi (Ficus Tsiela?) is well beaten and bruised, and mixed with water. Some milk is added to this mixture, which is sprinkled both inside and outside the hut. Only after this do they think that the hut and compound are purified. Among the Cherumas of Palghat, the pollution lasts for ten days.

“The ear-boring ceremony is performed during the sixth or seventh year. The Vallon, who is invited, bores the ears with a sharp needle. The wound is healed by applying cocoanut oil, and the hole is gradually widened by inserting cork, a wooden plug, or a roll of palm leaves. The castemen of the village are invited, and fed. The landlord gives the parents of the girl three paras of paddy, and this, together with what the guests bring, goes to defray the expenses of the ceremony. After the meal they go, with drum-beating, to the house of the landlord, and present him with a para of beaten rice, which is distributed among his servants. The ear-borer receives eight edangazhis of paddy, a cocoanut, a vessel of rice, and four annas.

“A woman found to be having intercourse with a Paraya is outcasted. She becomes a convert to Christianity or Mahomedanism. If the irregularity takes place within the caste, she is well thrashed, and prevented from resorting to the bad practice. In certain cases, when the illicit connection becomes public, the castemen meet with their Vallon, and conduct a regular enquiry into the matter, and pronounce a verdict upon the evidence. If a young woman becomes pregnant before marriage, her lover, should he be a Pulaya, is compelled to marry her, as otherwise she would be placed under a ban. If both are married, the lover is well thrashed, and fined. The woman is taken before a Thandan (Izhuva headman), who, after enquiry, gives her the water of a tender cocoanut, which she is asked to drink, when she is believed to be freed from the sin. Her husband may take her back again as his wife, or she is at liberty to marry another. The Thandan gets a few annas, betel leaves and areca nuts, and tobacco. Both the woman’s father and the lover are fined, and the fine is spent in the purchase of toddy, which is indulged in by those present at the time. In the northern parts of the State, there is a custom that a young woman before marriage mates with one or two paramours with the connivance of her parents. Eventually one of them marries her, but this illicit union ceases at once on marriage.”

Of the death ceremonies among the Cherumas of South Malabar, I gather that “as soon as a Cheruman dies, his jenmi or landlord is apprised of the fact, and is by ancient custom expected to send a field spade, a white cloth, and some oil. The drummers of the community are summoned to beat their drums in announcement of the sad event. This drumming is known as parayadikka. The body is bathed in oil, and the near relatives cover it over with white and red cloths, and take it to the front yard. Then the relatives have a bath, after which the corpse is removed to the burying ground, where a grave is dug. All those who have come to the interment touch the body, which is lowered into the grave after some of the red cloths have been removed. A mound is raised over the grave, a stone placed at the head, another at the feet, and a third in the centre. The funeral cortège, composed only of males, then returns to the house, and each member takes a purificatory bath. The red cloths are torn into narrow strips, and a strip handed over as a sacred object to a relative of the deceased. Meanwhile, each relative having on arrival paid a little money to the house people, toddy is purchased, and served to the assembly.

The mourners in the house have to fast on the day of the death. Next morning they have a bath, paddy is pounded, and gruel prepared for the abstainers. An elder of the community, the Avakāsi, prepares a little basket of green palm leaves. He takes this basket, and hangs it on a tree in the southern part of the compound (grounds). The gruel is brought out, and placed on a mortar in the same part of the compound. Spoons are made out of jack (Artocarpus integrifolia) leaves, and the elder serves out the gruel. Then the relatives, who have gathered again, make little gifts of money and rice to the house people. Vegetable curry and rice are prepared, and served to the visitors. A quaint ceremony called ooroonulka is next gone through. A measure of rice and a measure of paddy in husk are mixed, and divided into two shares.

Four quarter-anna pieces are placed on one heap, and eight on the other. The former share is made over to the house people, and from the latter the Avakāsi removes four of the coins, and presents one to each of the four leading men present. These four men must belong to the four several points of the compass. The remaining copper is taken by the elder. From his share of rice and paddy he gives a little to be parched and pounded. This is given afterwards to the inmates. The visitors partake of betel and disperse, being informed that the Polla or post-obituary ceremony will come off on the thirteenth day. On the forenoon of this day, the relatives again gather at the mourning place. The inmates of the house bathe, and fish and rice are brought for a meal.

A little of the fish is roasted over a fire, and each one present just nibbles at it. This is done to end pollution. After this the fish may be freely eaten. Half a seer or a measure of rice is boiled, reduced to a pulpy mass, and mixed with turmeric powder. Parched rice and the powder that remains after the rice has been pounded, a cocoanut and tender cocoanut, some turmeric powder, plantain leaves, and the rice that was boiled and coloured with turmeric, are then taken to the burial ground by the Avakāsi, a singer known as a Kallādi or Moonpatkāren, and one or two close relatives of the departed. With the pulped rice the elder moulds the form of a human being. At the head of the grave a little mound is raised, cabalistic lines are drawn across it with turmeric, and boiled rice powder and a plantain leaf placed over the lines. The cocoanut is broken, and its kernel cut out in rings, each of which is put over the effigy, which is then placed recumbent on the plantain leaf.

Round the mound, strings of jungle leaves are placed. Next the elder drives a pole into the spot where the chest of the dead person would be, and it is said that the pole must touch the chest. On one side of the pole the tender cocoanut is cut and placed, and on the other a shell containing some toddy. Then a little copper ring is tied on to the top of the pole, oil from a shell is poured over the ring, and the water from the tender cocoanut and toddy are in turn similarly poured. After this mystic rite, the Kallādi starts a mournful dirge in monotone, and the other actors in the solemn ceremony join in the chorus. The chant tells of the darkness and the nothingness that were before the creation of the world, and unfolds a fanciful tale of how the world came to be created. The chant has the weird refrain Oh! ho! Oh! ho. On its conclusion, the effigy is left at the head of the grave, but the Kallādi takes away the pole with him. The performers bathe and return to the house of mourning, where the Kallādi gets into a state of afflation. The spirit of the departed enters into him, and speaks through him, telling the mourners that he is happy, and does not want them to grieve over much for him.

The Kallādi then enters the house, and, putting a heap of earth in the corner of the centre room, digs the pole into it. A light is brought and placed there, as also some toddy, a tender cocoanut, and parched rice. The spirit of the deceased, speaking again through the Kallādi, thanks his people for their gifts, and beseeches them to think occasionally of him, and make him periodical offerings. The assembly then indulge in a feed. Rice and paddy are mixed together and divided into two portions, to one of which eight quarter-annas, and to the other twelve quarter-annas are added. The latter share falls to the Avakāsi, while from the former the mixture and one quarter-anna go to the Kallādi, and a quarter-anna to each of the nearest relatives. The basket which had been hung up earlier in the day is taken down and thrown away, and the jenmi’s spade is returned to him.”37

It is noted by Mr. Logan that “the Cherumans, like other classes, observe death pollution. But, as they cannot at certain seasons afford to be idle for fourteen days consecutively, they resort to an artifice to obtain this end. They mix cow-dung and paddy, and make it into a ball, and place the ball in an earthen pot, the mouth of which they carefully close with clay. The pot is laid in a corner of the hut, and, as long as it remains unopened, they remain free from pollution, and can mix among their fellows. On a convenient day they open the pot, and are instantly seized with pollution, which continues for forty days. Otherwise fourteen days consecutive pollution is all that is required. On the forty-first or fifteenth day, as the case may be, rice is thrown to the ancestors, and a feast follows.”

The following account of the death ceremonies is given by Mr. Anantha Krishna Iyer. “When a Pulayan is dead, the castemen in the neighbourhood are informed. An offering is made to the Kodungallūr Bhagavati, who is believed by the Pulayas to watch over their welfare, and is regarded as their ancestral deity. Dead bodies are generally buried. The relatives, one by one, bring a new piece of cloth, with rice and paddy tied at its four corners, for throwing over the corpse. The cloth is placed thereon, and they cry aloud three times, beating their breasts, after which they retire. A few Parayas are invited to beat drums, and play on their musical instruments—a performance which is continued for an hour or two. After this, a few bits of plantain leaves, with rice flour and paddy, are placed near the corpse, to serve as food for the spirit of the dead. The bier is carried to the graveyard by six bearers, three on each side. The pit is dug, and the body covered with a piece of cloth.

After it has been lowered into it, the pit is filled in with earth. Twenty-one small bits of leaves are placed over the grave, above the spot where the mouth of the dead man is, with a double-branched twig fixed to the centre, a cocoanut is cut open, and its water is allowed to flow in the direction of the twig which represents the dead man’s mouth. Such of the members of the family as could not give him kanji (rice gruel) or boiled rice before death, now give it to him. The six coffin-bearers prostrate themselves before the corpse, three on each side of the grave. The priest then puts on it a ripe and tender cocoanut for the spirit of the dead man to eat and drink. Then all go home, and indulge in toddy and aval (beaten rice). The priest gets twelve measures of rice, the grave-diggers twelve annas, the Vallon two annas, and the coffin-bearers each an anna. The son or nephew is the chief mourner, who erects a mound of earth on the south side of the hut, and uses it as a place of worship. For seven days, both morning and evening, he prostrates himself before it, and sprinkles the water of a tender cocoanut on it.

On the eighth day, his relatives, friends, the Vallon, and the devil-driver assemble together. The devil-driver turns round and blows his conch, and finds out the position of the ghost, whether it has taken up its abode in the mound, or is kept under restraint by some deity. Should the latter be the case, the ceremony of deliverance has to be performed, after which the spirit is set up as a household deity. The chief mourner bathes early in the morning, and offers a rice-ball (pinda bali) to the departed spirit. This he continues for fifteen days. On the morning of the sixteenth day, the members of the family bathe to free themselves from pollution, and their enangan cleans the hut and the compound by sweeping and sprinkling water mixed with cow-dung. He also sprinkles the members of the family, as they return after the bath. The chief mourner gets shaved, bathes, and returns to the hut. Some boiled rice, paddy, and pieces of cocoanut, are placed on a plantain leaf, and the chief mourner, with the members of his family, calls on the spirit of the dead to take them. Then they all bathe, and return home. The castemen, who have assembled there by invitation, are sumptuously fed. The chief mourner allows his hair to grow as a sign of mourning (diksha), and, after the expiry of the year, a similar feast is given to the castemen.”

The Cherumans are said by Mr. Gopal Panikkar to “worship certain gods, who are represented by rude stone images. What few ceremonies are in force amongst them are performed by priests selected from their own ranks, and these priests are held in great veneration by them. They kill cocks as offerings to these deities, who are propitiated by the pouring on some stones placed near them of the fresh blood that gushes from the necks of the birds.” The Cherumans are further said to worship particular sylvan gods, garden deities, and field goddesses. In a note on cannibalism the writer states that “some sixteen years ago a Nair was murdered in Malabar by some Cherumans. The body was mutilated, and, on my asking the accused (who freely confessed their crime) why had this been done? they answered ‘Tinnāl pāpam tīrum, i.e., if one eats, the sin will cease’.” It is a common belief among various castes of Hindus that one may kill, provided it is done for food, and this is expressed in the proverb Konnapāvam thīnnāl thirum, or the sin of killing is wiped away by eating. The Cheruman reply probably referred only to the wreaking of vengeance, and consequent satisfaction, which is often expressed by lower classes in the words pasi thirndadu, or hunger is satisfied.

Concerning the religion of the Pulayas, Mr. Anantha Krishna Iyer writes as follows. “The Pulayas are animists, but are slowly coming on to the higher forms of worship. Their gods are Parakutty, Karinkutty, Chathan, and the spirits of their ancestors. Offerings to these gods are given on Karkadaka and Makara Sankrantis, Onam, Vishu, and other auspicious days, when one of the Pulayas present turns Velichapad (oracle), and speaks to the assembly as if by inspiration. They are also devout worshippers of Kali or Bhagavati, whose aid is invoked in all times of danger and illness. They take part in the village festivals celebrated in honour of her. Kodungallur Bhagavati is their guardian deity. The deity is represented by an image or stone on a raised piece of ground in the open air. Their priest is one of their own castemen, and, at the beginning of the new year, he offers to the goddess fowls, fruits, and toddy.

The Pulayas also believe that spirits exercise an influence over the members of their families, and therefore regular offerings are given to them every year on Sankranti days. The chief festivals in which the Pulayas take part are the following:—

1. Pooram Vela.—This, which may be described as the Saturnalia of Malabar, is an important festival held at the village Bhagavati temple. It is a festival, in which the members of all castes below Brāhmans take part. It takes place either in Kumbham (February–March), or Meenam (March–April). The Cherumas of the northern part, as well as the Pulayas of the southern parts of the State, attend the festival after a sumptuous meal and toddy drinking, and join the procession. Toy horses are made, and attached to long bamboo poles, which are carried to the neighbourhood of the temple. As they go, they leap and dance to the accompaniment of pipe and drum. One among them who acts as a Velichapad (devil-dancer) goes in front of them, and, after a good deal of dancing and loud praying in honour of the deity, they return home.

2. Vittu Iduka.—This festival consists in putting seeds, or bringing paddy seeds to the temple of the village Bhagavati. This also is an important festival, which is celebrated on the day of Bharani, the second lunar day in Kumbham. Standing at a distance assigned to them by the village authorities, where they offer prayers to Kali, they put the paddy grains, which they have brought, on a bamboo mat spread in front of them, after which they return home. In the Chittūr tāluk, there is a festival called Kathiru, celebrated in honour of the village goddess in the month of Vrischikam (November-December), when these people start from the farms of their masters, and go in procession, accompanied with the music of pipe and drum. A special feature of the Kathiru festival is the presence, at the temple of the village goddess, of a large number of dome-like structures made of bamboo and plantain stems, richly ornamented, and hung with flowers, leaves, and ears of corn. These structures are called sarakootams, and are fixed on a pair of parallel bamboo poles. These agrestic serfs bear them in grand processions, starting from their respective farms, with pipe and drum, shouting and dancing, and with fireworks. Small globular packets of palmyra leaves, in which are packed handfuls of paddy rolled up in straw, are also carried by them in huge bunches, along with the sarakootams. These packets are called kathirkootoos (collection of ears of corn), and are thrown among the crowd of spectators all along the route of the procession, and also on arrival at the temple. The spectators, young and old, scramble to obtain as many of the packets as possible, and carry them home. They are then hung in front of the houses, for it is believed that their presence will help in promoting the prosperity of the family until the festival comes round again next year. The greater the number of these trophies obtained for a family by its members, the greater, it is believed, will be the prosperity of the family. The festival is one of the very few occasions on which Pulayas and other agrestic serfs, who are supposed to impart, so to speak, a long distant atmospheric pollution, are freely allowed to enter villages, and worship in the village temples, which generally occupy central positions in the villages. Processions carrying sarakootams and kathirkootoos start from the several farms surrounding the village early enough to reach the temple about dusk in the evening, when the scores of processions that have made their way to the temple merge into one great concourse of people. The sarakootams are arranged in beautiful rows in front of the village goddess. The Cherumas dance, sing, and shout to their hearts content. Bengal lights are lighted, and fireworks exhibited. Kathirkootoos are thrown by dozens and scores from all sides of the temple. The crowd then disperses. All night, the Pulayas and other serfs, who have accompanied the procession to the temple, are, in the majority of cases, fed by their respective masters at their houses, and then all go back to the farms.

3. Mandalam Vilakku.—This is a forty-one days’ festival in Bhagavati temples, extending from the first of Vrischikam (November-December) to the tenth of Dhanu (December-January), during which temples are brightly illuminated both inside and outside at night. There is much music and drum-beating at night, and offerings of cooked peas or Bengal gram, and cakes, are made to the goddess, after which they are distributed among those present. The forty-first day, on which the festival terminates, is one of great celebration, when all castemen attend at the temple. The Cherumas, Malayars, and Eravallars attend the festival in Chittūr. They also attend the Konga Pata festival there. In rural parts of the State, a kind of puppet show performance (olapava koothu) is acted by Kusavans (potters) and Tamil Chettis, in honour of the village deity, to which they contribute their share of subscription. They also attend the cock festival of Cranganore, and offer sacrifices of fowls.”

For the following note on the religion of the Pulayas of Travancore, I am indebted to Mr. N. Subramani Iyer. “The Pulayas worship the spirits of deceased ancestors, known as Chāvars. The Mātan, and the Anchu Tamprakkal, believed by the better informed section of the caste to be the five Pāndavas, are specially adored. The Pulayas have no temples, but raise squares in the midst of groves, where public worship is offered. Each Pulaya places three leaves near each other, containing raw rice, beaten rice, and the puveri (flowers) of the areca palm. He places a flower on each of these leaves, and prays with joined hands. Chāvars are the spirits of infants, who are believed to haunt the earth, harassed by a number of unsatisfied cravings. This species of supernatural being is held in mingled respect and terror by Pulayas, and worshipped once a year with diverse offerings.

Another class of deities is called Tēvaratumpuran, meaning gods whom high caste Hindus are in the habit of worshipping at Parassalay; the Pulayas are given certain special concessions on festival days. Similar instances may be noted at Ochira, Kumaranallur, and Nedumangad. At the last mentioned shrine, Mateer writes, ‘where two or three thousand people, mostly Sudras and Izhuvas, attend for the annual festival in March, one-third of the whole are Parayas, Kuravas, Vēdars, Kanikkars, and Pulayas, who come from all parts around. They bring with them wooden models of cows, neatly hung over, and covered, in imitation of shaggy hair, with ears of rice. Many of these images are brought, each in a separate procession from its own place. The headmen are finely dressed with cloths stained purple at the edge. The image is borne on a bamboo frame, accompanied by a drum, and men and women in procession, the latter wearing quantities of beads, such as several strings of red, then several of white, or strings of beads, and then a row of brass ornaments like rupees, and all uttering the Kurava cry. These images are carried round the temple, and all amuse themselves for the day.’ By far the most curious of the religious festivals of the Pulayas is what is known as the Pula Saturday in Makaram (January-February) at Sastamkotta in the Kunnattur tāluk.

It is an old observance, and is most religiously gone through by the Pulayas every year. The Valluvan, or caste priest, leads the assembled group to the vicinity of the banyan tree in front of the temple, and offerings of a diverse nature, such as paddy, roots, plantain fruits, game, pulse, coins, and golden threads are most devoutly made. Pulayas assemble for this ceremony from comparatively distant places. A deity, who is believed to be the most important object of worship among the Pulayas, is Utaya Tampuran, by which name they designate the rising sun. Exorcism and spirit-dancing are deeply believed in, and credited with great remedial virtues. The Kokkara, or iron rattle, is an instrument that is freely used to drive out evil spirits. The Valluvan who offers animal sacrifices becomes immediately afterwards possessed, and any enquiries may be put to him without it being at all difficult for him to furnish a ready answer. In North Travancore, the Pulayas have certain consecrated buildings of their own, such as Kamancheri, Omkara Bhagavathi, Yakshi Ampalam, Pey Koil, and Valiyapattu Muttan, wherein the Valluvan performs the functions of priesthood. The Pulayas believe in omens. To see another Pulaya, to encounter a Native Christian, to see an Izhuva with a vessel in the hand, a cow behind, a boat containing rice or paddy sacks, etc., are regarded as good omens. On the other hand, to be crossed by a cat, to see a fight between animals, to be encountered by a person with a bundle of clothes, to meet people carrying steel instruments, etc., are looked upon as very bad omens. The lizard is not believed to be a prophet, as it is by members of the higher castes.”

Concerning the caste government of the Pulayas of Travancore, Mr. Subramania Iyer writes as follows. “The Ayikkara Yajamanan, or Ayikkara Tamara (king) is the head of the Pulaya community. He lives at Vayalar in the Shertalley tāluk in North Travancore, and takes natural pride in a lace cap, said to have been presented to one of his ancestors by the great Cheraman Perumāl. Even the Parayas of North Travancore look upon him as their legitimate lord. Under the Tamara are two nominal headmen, known as Tatteri Achchan and Mannat Koil Vallon. It is the Ayikkara Tamara who appoints the Valluvans, or local priests, for every kara, for which they are obliged to remunerate him with a present of 336 chuckrams. The Pulayas still keep accounts in the earliest Travancorean coins (chuckrams).

The Valluvan always takes care to obtain a written authority from the Tamara, before he begins his functions. For every marriage, a sum of 49 chuckrams and four mulikkas have to be given to the Tamara, and eight chuckrams and one mulikka to the Valluvan. The Valluvan receives the Tamara’s dues, and sends them to Vayalar once or twice a year. Beyond the power of appointing Valluvans and other office-bearers, the authority of the Tamara extends but little. The Valluvans appointed by him prefer to call themselves Head Valluvans, as opposed to the dignitaries appointed in ancient times by temple authorities and other Brāhmans, and have a general supervising power over the Pulayas of the territory that falls under their jurisdiction. Every Valluvan possesses five privileges, viz., (1) the long umbrella, or an umbrella with a long bamboo handle; (2) the five-coloured umbrella; (3) the bracelet of honour; (4) a long gold ear-ring; (5) a box for keeping betel leaves. They are also permitted to sit on stools, to make use of carpets, and to employ kettle-drums at marriage ceremonials. The staff of the Valluvan consists of (1) the Kuruppan or accountant, who assists the Valluvan in the discharge of his duties; (2) the Komarattan or exorciser; (3) the Kaikkaran or village representative; (4) the Vatikkaran, constable or sergeant. The Kuruppan has diverse functions to perform, such as holding umbrellas, and cutting cocoanuts from trees, on ceremonial occasions. The Vatikkaran is of special importance at the bath that succeeds a Pulaya girl’s first [90]menses. Adultery is looked upon as the most heinous of offences, and used to be met with condign punishment in times of old. The woman was required to thrust her hand into a vessel of boiling oil, and the man was compelled to pay a fine of 336 or 64 chuckrams, according as the woman with whom he connected himself was married or not, and was cast out of society after a most cruel rite called Ariyum Pirayum Tittukka, the precise nature of which does not appear to be known. A married woman is tried by the Valluvan and other officers, when she shows disobedience to her husband.”

It is noted by Mr. Anantha Krishna Iyer, that, “in the Palghat tāluk of South Malabar, it is said that the Cherumas in former times used to hold grand meetings for cases of theft, adultery, divorce, etc., at Kannati Kutti Vattal. These assemblies consisted of the members of their caste in localities between Valayar forests and Karimpuzha (in Valluvanād tāluk), and in those between the northern and southern hills. It is also said that their deliberations used to last for several days together. In the event of anybody committing a crime, the punishment inflicted on him was a fine of a few rupees, or sometimes a sound thrashing. To prove his innocence, a man had to swear ‘By Kannati Swarupam (assembly) I have not done it.’ It was held so sacred that no Cheruman who had committed a crime would swear falsely by this assembly. As time went on, they found it difficult to meet, and so left off assembling together.”

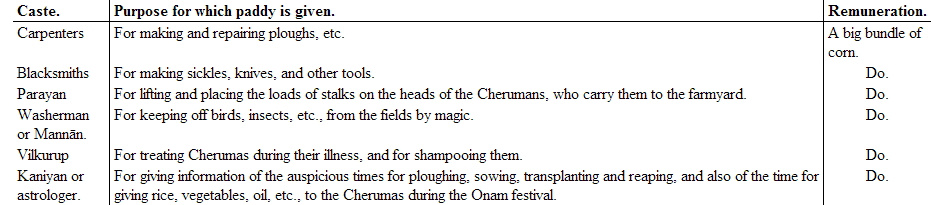

In connection with the amusements of the Pulayas, Mr. Anantha Krishna Iyer writes that “their games appear to be connected in some way with their religious observances. Their favourite dance is the kole kali, or club dance. A party of ten or twelve men, provided with sticks, each a yard in length, stand in a circle, and [91]move round, striking at the sticks, keeping time with their feet, and singing at the same time. The circle is alternately widened and narrowed. Vatta kali is another wild dance. This also requires a party of ten or twelve men, and sometimes young women join them. The party move in a circle, clapping their hands while they sing a kind of rude song. In thattinmel kali, four wooden poles are firmly stuck in the ground, two of which are connected by two horizontal pieces of wood, over which planks are arranged. A party of Pulayas dance on the top of this, to the music of their pipe and drum. This is generally erected in front of the Bhagavati temple, and the dancing takes place immediately after the harvest. This is intended to propitiate the goddess. Women perform a circular dance on the occasions of marriage celebrations.” The Cherumas and Pulayas are, like the Koragas of South Canara, short of stature, and dark-skinned. The most important measurements of the Cherumans whom I investigated at Calicut were as follows:—