Burma, Population 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Population

The total population of the Province at the Census of 1901 was 10,490,624. This total includes, besides the residents of those areas .where a regular synchronous or non-synchronous Population.enumeration was carried out, the inhabitants of a few of the most backward of the Hill Tracts where the population could only be estimated. The estimated areas contained a popula- tion of 127,011, so that the aggregate of persons regularly treated was 10,363,613. For Burma proper, exclusive of the Shan States and the Chin Hills, the density in 1901 was 55 persons per square mile (49 in rural areas). In 1891 the corresponding figure was 46, and at the Census of 1881 it was 43 for what was then British (or Lower) Burma. Of the four natural divisions of the Province described above, the Lower Burma sub-deltaic is the most thickly populated. Its average is 90 persons per square mile, and one of its Districts (Henzada) shows the highest density of any of the rural Districts in the Province. The Upper Burma dry division comes second in order with 79 persons per square mile, and the Lower Burma littoral division follows with 55, Some of the Lower Burma littoral Districts can boast of a fairly dense population, but the divisional average is reduced by the hill areas of Arakan and Tenasserim, whose dwellers are exceed- ingly scattered. The Upper Burma wet division is far the least populous of the Province, its average being only 15 persons per square mile. The density for the whole of Burma, including the poorly populated areas which were enumerated for the first time in 1901 as well as Burma proper, is 44 persons per square mile (40 in rural areas).

In all, 989,938 of the persons dealt with at the last Census lived in towns and 9,500,686 in rural areas. Burma contained, in 1901, two cities (Rangoon and Mandalay) with more than 100,000 inhabi- tants, 19 towns with a population of over 10,000, and 25 with 5,000 and more. The following are the population totals for the principal towns: Rangoon, 234,881; Mandalay, 183,816; Moulmein, 58,446; Akyab, 35,680; Bassein, 31,864; Prome, 27,375; Henzada, 24,756; and Tavoy, 22,371. Villages with more than 500 inhabitants num- bered 2,447, ^id smaller villages 57,948. The Burmese village or hamlet is as a rule a very compact unit. Each house stands in its own separate compound or enclosure, and the whole collection of dwellings is often surrounded by a bamboo fence or a thorn hedge. For administrative purposes the village headman's charge consists ordinarily of several of these hamlets.

In Burma proper (that is, excluding the Shan States and the Chin Hills) the population rose during the ten years 1891 and 1901 from 7,722,053 to 9,252,875, or by 19-8 per cent. As Upper Burma was not dealt with in 1 881, it is not possible to make any further com- parison of the figures for the whole Province ; but in Lower Burma, which has now been British for over fifty years, the figures show that from 1872 to 1881 the rate of increase was 36 per cent., from 1881 to 1891 24-7 per cent., and from 1891 to 1901 2i«2 per cent. This large growth is due almost wholly to immigration from outside, which has no real emigration to counterbalance it : there is nothing to show that the excess of births over deaths within the Province is at all above the normal. The part that immigration plays in the movement of the population is strikingly brought out by the District figures, for without exception the rise is most marked in the rice- producing areas of the delta, which annually attract large numbers of agriculturists from Southern India. Prome, Mandalay, and Thayet- myo alone of the Districts of the Province showed a falling off in population at the Census of 1901, caused by the exodus of the indi- genous population to the more fertile areas of the Province, notably to the delta Districts.

The rate of increase during the ten years ending 1901 in the Lower Burma sub-deltaic division (of which Thayetmyo and Prome are typical Districts) is only 1 1 per cent. ; that of the Upper Burma dry (in which Mandalay figures) is only 1 per cent, higher ; and it is clear that the tendency is not only for the immigrant Indian population to collect in the wetter portions of the Province, but for residents of the less-favoured areas of the dry zone to move to the more prosperous rice-producing tracts. This relinquishment by the indigenous folk of the less fruitful localities of Lower Burma is a phenomenon of comparatively recent growth. There was no hint of any such movement during the years 1 881 -91, and in the case of Prome and Thayetmyo it cannot be said that the annexation of Upper Burma has helped to bring it about. No tendency exists on the part of the indigenous population to crowd from the rural areas into the towns. The Burman, fond as he is of gaiety and the amenities of cities, is quite incapable of responding to the calls that town life makes upon his energies. In industrial matters he finds it hopeless to compete with the native of India or the Chinaman ; and, though precluded by no caste prejudices from taking up fresh occupations, he soon learns that it is in the non-industrial pursuits of the country that he can best hold his own. There is, in fact, among the people of the country an inclination to forsake urban for rural areas.

In the six largest towns of the Province, though the number of foreigners, i.e. Hindus and Musalmans, was in almost every instance considerably higher in 1901 than in 1891, the total number of Buddhists was either lower than, or only slightly above, the earlier figure. In Upper Burma, where the urban population is recruited less from India than in Lower Burma, a surprisingly large number of towns declined in population within the decade preceding the Census of 1901. Mandalay, whose inhabitants have diminished by close upon 5,000 during the period in question, is a case in point, but there are other towns where the falling off is even more marked. During the preceding decade a decrease in the urban population was quite the exception. To a certain extent the diminution of recent years is due to the growing practice of building houses just outside municipal limits in order to avoid municipal taxation ; hut this tendency can be held responsible for a portion only of the general decrease, and everything seems to point to the gradual displacement of the Burman in the larger industrial centres and to the concentration of the indigenous folk into the large villages.

There is very little emigration from Burma. Practically all the people who leave are foreign immigrants returning to their homes either temporarily or permanently. The Burman himself rarely moves from the country of his birth. It is probable that at least one-half of the persons indigenous to Burma who were enumerated in India at the Census of 1901 were convicts undergoing terms of transportation in Indian jails.

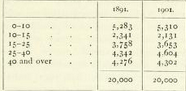

At the Census of 1891 the mean age of the population was returned as 24-57 years for males and 24-51 for females. In 1901 it was found to be 25-04 for the former, and 24-75 ^'^^ the latter. Though, judged by European standard.s, this mean is low, it is not below that of the other Provinces of India. A rise in the mean age, such as is apparent from the above data, is not always a satisfactory feature, but there appear to be good grounds for assuming that in the case of Burma it is not a decline in the birth-rate that has caused the figure to mount. The following figures give the distribution over five main age periods of every 20,000 of the population of the Province in 1891 and 1901 : —

The rise in the lowest age period, in so far as it does not represent

greater care devoted to infants during their earliest years, points to

a slightly improved birth-rate, while the increase in the highest age

period shows that there is no appreciable diminution in longevity.

Municipalities, cantonments, and towns are divided into wards for the purposes of the registration of births and deaths, and the headman appointed for revenue purposes is entrusted with the work of registering domestic occurrences as a portion of his regular duties. He sends his register of births and deaths at regular intervals to the town authorities, who compile monthly returns submitted to the Sanitary Commissioner. In rural areas, the headman of each village or col- lection of hamlets registers domestic occurrences on a form printed in counterfoil. A police patrol constable visits each village at least once a month, takes away the entries of all events recorded since his last visit and deposits these documents in the head-quarters station of the patrol, whence they are sent to township officers (subordinate magistrates and revenue officers) for compilation into monthly returns. Each township officer sends such returns to the Civil Surgeon of the District, in whose office a consolidated return for the whole District is made up and submitted to the Sanitary Commissioner. The book of counterfoils is retained by the headman, and is thus available for examination by inspecting officers.

The particulars registered differ slightly in different localities : thus, in those portions of Lower Burma where registration is in force, both births and deaths are recorded, while in rural areas in Upper Burma deaths alone are recorded.

The birth and death registers in towns, and the books of counterfoils in villages, are checked by District officials, and vaccinators are required to verify entries by house-to-house inquiries and through other collateral information obtained in the course of their vaccination duties. In towns possessing cemetery caretakers, a further check is maintained over death registers by comparison with the registers of burials. The entire Province has not, however, been brought under this system of registration, for there are tracts not accessible to patrols, such as the more mountainous parts and those inhabited by illiterate people or wild tribes. These are treated as excluded tracts, and their area aggregates roughly 54,000 square miles. Tracts not easily acces- sible to patrols, and with which communications are open only at certain seasons of the year, are considered as irregularly patrolled areas, and are treated separately in the annual returns of vital statistics. All others are regarded as regularly patrolled tracts.

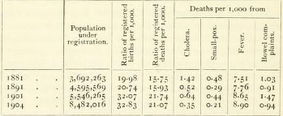

The following table gives details regarding the ratio of registered births and deaths for the years 1881, 1891, 1901, and 1904 : —

The rise under both heads during the two decades in question (a rise which, it may be observed, is very much more marked during the second than during the first) speaks eloquently of enhanced precision in registration ; but a comparison of even the most recent Burmese figures with the data obtained in countries where the system of record- ing vital statistics is admittedly within a measurable distance of absolute accuracy shows that there is still room for improvement in the record of births and deaths in the Province. Birth and death rates vary considerably from District to District, but no purpose would be served by a presentation of figures contrasting the highest and the lowest, except to show where registration was thorough and where the reverse.

Fever, bowel complaints, cholera, and small-pox are the most frequent causes of death in Burma. Since February, 1905, plague has established itself in Rangoon, has spread to a few Districts inland, and has not yet been eradicated. Fevers are of various kinds, malarial and other ; but it should be borne in mind, when considering the mortality statistics of the Province as a whole, that in the mouth of a Burman the expression pya thi (' to have fever ') is extraordinarily elastic and is usually made to cover, besides fevers proper, almost every disease which has no very marked outward symptoms and possesses no name of its own in Burmese. In certain localities, and at certain seasons of the year, dysentery and diarrhoea are lamentably rife. The larger urban areas of the Province are seldom without some sporadic cases of cholera, but it is only now and then that the disease appears in epidemic form. Vaccination during the past twenty years has enabled good headway to be made against small-pox, which in former days, judging by the large number of pock-marked Burmans that are met with, must have been a scourge of extreme virulence. Of the less serious diseases, worms, diseases of the eye and of the digestive organs, rheumatic affections, and venereal diseases are among the most prevalent.

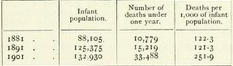

Infant mortality in Burma, judged by a European standard, is very high. How much of the existing state of things is due to a barbarous obstetrical system, and how much to carelessness after birth, is doubt- ful ; but it is clear from the returns abstracted below that one infant out of every four born in Burma dies before the first anniversary of its birthday.

The apparent increase in the mortality of children of under one year

of age from 12 to 25 per cent, is at first sight startling, for there are no

indications of greater neglect of their children on the part of indi-

genous parents or of greater sickliness among the infants. The rise is

in reality nothing more or less than a sign of more effective registra-

tion, and of the gradual disappearance of the belief, so common in

backward races, that the concerns of so unimportant a section of the

community as babies of less than one year are not a matter that can

possibly come in any way within the cognizance of Government.

Of the 10,490,624 persons shown in the census returns for 1901, 5,342,033 were males and 5,148,591 females. In other words, 50-9 per cent, of the population of Burma were of the male sex and 49-1 per cent, of the female, or for every i,coo males there were 962 females. The Census of 1891 showed a similar proportion. It has been held by competent observers that the ratio of females to males in a given race . is generally higher or lower according as woman occupies a better or a worse position in the social scale. The absolute freedom of the Burmese women, and the prominent part they play in the industrial no less than in the social life of the country, are phenomena that are very striking to those accustomed to the zanana life of India ; and one would expect the emancipated women of Burma to bear a higher proportion to the males than is the case in other parts of the Indian Empire. As a matter of fact, the ratio in Burma is lower than in several other Provinces. This is, however, due to immigration, the male immigrants exceeding the female to a very large extent. In the Districts that are but little resorted to by settlers from India the females are more numerous than the males, and they also predominate in the case of all the principal indigenous races except the Karens and the Talaings. The figures for Burmans are males 3,191,469 and females 3,317,213; for Shans, males 386,370 and females 400,717 ; and for Chins, males 89,008 and females 90,284. The question of female infanticide does not, fortunately, arise in Burma.

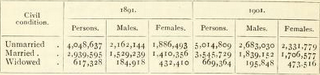

The following table gives statistics of civil condition in Burma proper, as recorded in 1891 and 1901 : —

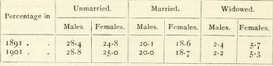

Reducing the figures to percentages, they work out thus

Marriage in Burma is a purely civil ceremony and has no religious conception underlying it. Matches are arranged by the parents of the young couple, or through the medium of a go-between, or merely with the mutual consent of the parties. The wedding is ordinarily made the occasion of a feast to which friends are invited, and during the course of which the bride and bridegroom join hands (Jet tat) and eat out of the same dish ; but this ceremony may be dispensed with. The mere fact of living and eating together as husband and wife is sufficient to constitute a legal union. Remarriage both of widows and widowers is common, and the widowed form only a small proportion of the popula- lation. Divorce is very freely resorted to, but is generally followed by a second marriage. The figures would appear to show that the readi- ness to embrace matrimony a second time has, if anything, increased during the last decade.

The statistics of civil condition by age periods show a rather higher total of married girls and boys of immature age in 1901 than in 1891, an increase for which the growth of Indian immigration during the decade is responsible, for infant marriage is not practised by the people of the country. They indicate further a slightly increased tendency on the part of the indigenous male to defer his marriage until after the twenty-fifth year of life. The matrimonial customs of the Kachins and Karens, which restrict their choice of wives to certain families or clans, appear to exercise an appreciable effect upon their readiness to marry. In their case the proportion of married to the total population is very much below that of the Burmans and the Shans. Polyandry is unknown, but polygamy exists, though not to such an extent as to produce any abnormal figures in the sex and civil condition return.

The indigenous languages of Burma belong, with two exceptions, to the Mon-Khmer and the Indo-Chinese families of language. The latter can be subdivided into two sub-families, the Tibeto-Burman and the Siamese-Chinese. Burmese, the most important of the languages of the Tibeto-Burman sub-family, was spoken by 7,006,495 persons in 1901. Arakanese, a dialect of Burmese, claimed 383,400 speakers in the same year. Kadu, the vernacular of a tribe in the north-west of the Province which is fast dropping out of use, has been placed pro- visionally in the Tibeto-Burman sub-family. The Census showed that in 1901 it was spoken by 16,30.0 persons, and that the Mro of the Arakan Hill Tracts, which has been similarly classified, was the speech of 13,414 inhabitants of Arakan. Kachin and Chin are also Tibeto- Burman languages, not quite so closely allied to Burmese as the others. Their vocabulary differs, but their structure bears a strong family resemblance to Burmese. Kachin was the language ordinarily used by 65,570 persons within the area treated regularly in 1901. A large pro- portion of the Kachin-speaking folk are inhabitants of the estimated areas, where language data were not collected, and it is probable that the aggregate of Kachin speakers in the Province is nearly double the figure given above. The Chin speakers numbered 176,323. There are various forms of Chin, but the only largely spoken variety that was not classified under the general head of Chin was the speech of the Kamis of Northern Arakan (24.3S9). The vernaculars of the Lisaws, the Muhsos, the Akhas, the Marus, and of a few other hill tribes in the north and east, are also comprised in the Tibeto-Burman sub-family,

Shan and Karen are the two main local representatives of the Siamese-Chinese sub-family. Shan proper was the vernacular of 750,473 persons in 1901, Karen of 704,835 persons. These totals do not include the speakers of the trans-Salween dialects of Shan known as Hkiin and Lii, or the quasi-Karen vernaculars of Karenni and its neighbourhood. Taungthu, which is practically a dialect of Karen, was spoken by 160,436 persons in 1901. Siamese and Chinese, the two most important non-indigenous tongues of the sub-family, are both spoken in Eurma, Siamese (19,531) for the most part in the extreme south, on the Siamese border, and Chinese (47,444) more or less through the whole of the Province by Chinese immigrants.

Talaing, the speech of the Mons or Peguans, who for many years strove with the Burmans for the mastery in Burma, belongs to the Mon- Khmer or Mon-Anam family, and was returned by 154,483 persons in 1901. Talaing as a spoken language is gradually dying out. its place being taken by Burmese. The remaining languages of the Mon-Khmer family spoken in the Province are the vernaculars of various hill tribes scattered through the Shan States, such as the Was, the Palaungs, the Riangs, and the Danaws. Palaung was the speech of 51,121 persons in 1 90 1. Wa is spoken largely to the east of the Salween, but the majority of its speakers were entirely excluded from the census opera- tions and their number is not even approximately known.

The only two vernaculars of Burma that do not belong to either of the two families are Daingnet, a corrupt form of Bengali spoken in Akyab District near the borders of Chittagong ; and Salon (Selung), the speech of the sea-gipsies of the Mergui Archipelago, which has been placed in the Malay language family. The Malayo-Polynesian languages, though related to the Mon-Khmer family, have been separated from that group, because the relationship has not yet been definitely settled.

The proportion borne by the speakers of the chief vernaculars of the Province (namely, Burmese, Shan, Karen, Talaing, Chin, and Kachin) to the population of Burma proper in 1891 and 1901 is indicated in the statement below : —

The following are the totals of persons returned in 1901 as speakers of the principal non-indigenous languages belonging to language families other than the Indo-Chinese : —

Caste is absolutely unknown as an indigenous institution in Burma. It is foreign to the democratic temperament of the people, and an ethnical analysis of the inhabitants of the country must of necessity be based on considerations other than that of caste. In existing con- ditions, the most satisfactory classification of the indigenous races of Burma is that which proceeds on a linguistic basis. Of the total popu- lation in 1901, 6,508,682, or 62 per cent., were Burmans. Of the other Tibeto-Burman peoples, the Arakanese of the western coast numbered 405,143, the Kadus of Katha 34,629, and the Mros of Akyab and Northern Arakan 12,622. The Inthas, a community found scattered through the Southern Shan States, numbered 50,478, though only 5,851 of them spoke the Intha dialect. The Kachins occupy the hills to the extreme north of Upper Burma, and are steadily making their way southwards down the eastern fringe of the Province ; 64,405 of them came within the scope of the regular census operations in 1901, and about 50,000 were residents of the estimated tracts, where no regular collection of race statistics was made.

The Chins {see Chin Hills) are the predominant folk along the western border of Burma from the level of Manipur down to Akyab District, and thence southwards along the range of hills that separates the old province of Arakan from the Irrawaddy valley. The Chins proper numbered 179,292 in 1901, and the Kamis of Akyab and Northern Arakan, a closely allied tribe, 24>937- The Danus (63,549) are a half-bred Shan-Burmese community inhabiting the borderland between Burma and the Shan States ; and the Taungyos (16,749) are also borderers, frequenting the same region and talking a language which resembles an archaic form of Burmese. The Akhas or Kaws, a hill tribe of the trans-Salween Shan States, come probably from the same prehistoric stock as the Burmans, the Kachins, and the Chins ; so also, there is reason to believe, do the Lisaws, the Muhsos, the Maingthas, the Szis, the Lashis, and the Marus of the north-eastern hills. The Akhas numbered 26,020 in 1901 ; the Muhsos, 15,774 ; the Kwis, a branch of the Muhsos, 2,882 ; the Lisaws, 1,427. The remaining tribes are for the most part inhabitants of the areas estimated at the Census of 1901, and their strength is but imperfectly known.

In the Siamese-Chinese group the Shans and Karens are most

strongly represented. The total number of Shans in 1901 was 787,087

(exclusive of the Lem, the Hkiin, and the Lii of trans-Sahveen territory,

but including the Shan Tayoks of the Chinese border). The Shans

{see Shan States) are the prevailing nationality in practically the

whole of the uplands that lie between the Irrawaddy and the Mekong

from the 20th to the 24th parallels of latitude, and form a large pro-

portion of the population in the country that separates the western bank

of the Irrawaddy from the Manipur and Assam frontiers. West of the

Irrawaddy they have become absorbed to some extent into the Burman

communities that surround them, and nearly the whole of their territory

forms part of the regularly administered areas of the Province ; but east

of the river they have preserved their race characteristics unimpaired,

and are administered through the native rulers of the States into which

their country is politically divided.

The Karens are the hill tribes of the south-eastern areas of the Province from Toungoo to Mergui, and are also found scattered over the delta of the Irrawaddy. The greater number of the Karens of Lower Burma are members of one or other of two main tribes, the Sgaw and the Pwo. Towards the north and beyond the limits of Lower Burma, in Karenni and the Southern Shan States, a third tribe, the Bghai, preponderates. In 1901 a total of 86,434 persons returned themselves as Sgaw, and 174,070 as Pwo Karens, the tribe in the case of 457,355 others being not returned. The Bghai were for the most part residents of the estimated areas of Karenni when the Census took place. Within territory treated regu- larly, 4,936 Red Karens (Bghai) were enumerated. The Bres, the Padaungs, and the Zayeins of Karenni and its neighbourhood have been classed linguistically with the Bghai, though it is possible that further research may show that ethnically they should be placed in some other category. In all, 7,825 Padaungs and 4,440 Zayeins were found in areas within the scope of the regular Census. They were practically all residents of the south-western corner of the Southern Shan States. The Taungthus, like the Padaungs and the Zayeins, are of doubtful origin.

They are found in the hills along the eastern border of Burma from Amherst to Yamethin, and numbered 168,301 in 1901. Their language is to all intents and purposes a form of Karen, and it is probable that there is more Karen than any other element in their composition.

The Talaings are the main representatives of the Mon-Anam group in Burma proper. They are found in their greatest strength in the country round the mouths of the Irrawaddy, the Sittang, and the Salween, which formed the nucleus of the ancient kingdom of Pegu. In 1 90 1 their aggregate was 321,898. Their numbers are diminishing, and they are being gradually absorbed into the Burmese population of the Province. Of the Mon-Anam hill tribes of the Shan States the most numerous according to the census figures of lyoi are the Palaungs (56,866), who are found for the most part m the Ruby Mines District and the hills that form the northern border of the Northern Shan States.

It is probable that the Was, whose country lies to the east of the Palaung tract on the farther side of the Salween, are as numerous as the Palaungs ; but, as their northern areas were untouched at the time of the Census, nothing is known of their real strength. In the regularly enumerated areas in the trans-Salween Shan States 5,964 persons were returned as Was, 15,660 as Tai Loi, 1,351 as Hsen Hsum, and 1,096 as Pyin. The last three tribes are, it is believed, varieties of the Wa stock. The Riangs or Yins are almost certainly, and the Danaws probably, of Mon-Anam extraction. The latter, who numbered only 635 in 1 901, are almost extinct as a separate tribe. They inhabit the Myelat States to the east of Upper Burma. The Yins numbered 3,094 at the last Census. Their habitat lies in the north-east of the Southern Shan States.

There are no very marked differences in the physical characteristics of the indigenous races of the Province. Like all southern Mongolians, their stature is below the average. They are thick-set and for the most part sturdy. Their complexion ranges through various shades of olive- brown, and is darker on the whole than that of the Chinese ; their hair is black and straight and on the face ordinarily very sparse. It is usually left long on the head and in most cases is tied into a top-knot. They are round-headed or brachycephalic, have high cheek-bones and broad noses. Their eyes are small and black but not as markedly oblique as those of the Chinese ; and, taken as a whole, they show a greater tendency to approximate to the Caucasian type than do the latter.

Of the Hindu castes the following show the largest totals : Paraiyan, 25,601; Mala, 18,522 ; Kapu, 11,214; Palli, 13,250; Brahman, 15,922 ; Chhatri or Rajput, 13,454. A total of 41,663 males and 7,758 females were returned in the census schedules under the general designation of Sudra. Among the Musalman tribes the Shaikhs are numerically the most important in Burma, and their total of 269,042 represents 80 per cent, of the Muhammadan population of the Province. Saiyids and Pathans numbered respectively 8,970 and 9,224; and Zairbadis, the offspring of unions between Burmese women and Musalman natives of India, 20,423.

The British in Burma in 1901 numbered 7,450 (5,948 of whom were males and 1,502 females), and the Eurasians 8,884. A total of 1,090 persons were returned as Europeans, no nationality being given. It is probable that the majority of these were, strictly speaking, Eurasians. The Chinese of the Province aggregated 62,486, as against 41,457 in 1891.

Of the religions of Burma, Buddhism has by far the largest number of professed adherents. In 1901 a total of 9,184,121 persons, or 88-6 per cent, of the population, were returned as Buddhists. The Buddhism of Burma is an amalgam that has resulted from a fusion of the elements of the Northern and the Southern schools of Buddhist thought, introduced from India on the one hand and from Ceylon on the other. This amalgamation was, as already stated, completed at Pagan in the eleventh century. Before that, a corrupt form of Buddh. ism prevailed, which appears to have been an admixture of Lamaism and Tantric Buddhism, its professors being called the Ari or Ariya^ the 'noble.' Their robes were dyed with indigo, like those of the Lamas of Tibet and China, and they wore their hair at least two inches long. They were not strict observers of the vow of celibacy, and the basis of their doctrines was that sin could be expiated by the recitation of certain hymns.

In theory Buddhism is the general religion of the country. In point of fact, though it has done much to soften and humanize the people, it is far too often nothing more than an outward veneer covering the spirit-worship that is everywhere practised openly, one might almost say shamelessly. The Burmese Buddhist Church is split up into two main parties, which are known as the Sulagandi and the Mahagandi.

The members of the former set store by ritual and outward observances ; those of the latter are to all intents and purposes fatalists, but the differences between the two parties are largely academic. Sectarian bitterness is practically unknown. There are various minor sects, but none has achieved any marked distinction. The head of the Church in Upper Burma is the thathanabaing or archbishop ; and in both sec- tions of the Province there is a recognized hierarchy, which comprises dignitaries known as gaingoks (bishops) and gaingdaukSy as well as the ordinary potigyis or monks. The religion of the people finds an outward and visible sign in the pagodas and monasteries that are prominent features of nearly every village. The Burmese pagoda is bell-shaped, built of brick and usually whitewashed, though many shrines are partially, and a few wholly, gilded. Timber is the material ordinarily used for the kyaungs or monasteries that the pious have erected in thousands through the length and breadth of the Province, and enormous sums are frequently lavished on these and other works of merit. The monasteries are the indigenous schools of Burma, at which the village boys all learn to read and write. It is not only as scholars, moreover, that the people have had experience of their kyaungs. Prac- tically every male Burman assumes the yellow robe of a monk for a shorter or longer period as the case may be, and monasticism thus plays a part in the life of the inhabitants of the country that is absolutely unique.

Next to the Buddhists in point of numbers come the spirit-worshippers or Animists, the majority of whom inhabit the Hill Tracts. Their aggre- gate in 1901 was 399,390. This figure does not, however, adequately represent the strength of Animism in Burma, for it does not include the residents of the estimated areas where no religion data were col- lected at the enumeration. The population of these areas amounted to 127,011 ; and, as there is good reason to beHeve that it was made up very largely of spirit-worshippers, the actual strength of the Animists may be fixed at something approaching half a million.

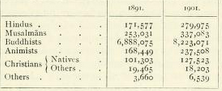

Islam was represented at the latest Census by 339,446 persons, and Hinduism by 285,484. After these, but separated from them by a con- siderable numerical gap, come Christians with a total of 147,525, of whom 129,191 were natives, while the adherents of the other religions, most of whom were Sikhs, totalled only 7,647. The largest proportional increase during the decade ending 1901 is among the Animists, who at the close of this p riod were shown as more than twice as numerous as at its beginning ; but this is due solely to the fact that the Census of 1 90 1 dealt with several large backward hill areas inhabited by spirit- worshipping tribes who were untouched in 189 1. A comparison of the totals in each year for Burma proper gives a better idea of the relative growth of the main religions. On this basis we find that during the period in question Hindus have increased at the rate of 63 per cent., Animists at 41, Musalmans at t^t^. Christians at 21, and Buddhists at 19 per cent. The last figure may be looked upon as indicating roughly the natural rate of increase in the Province, the conversions from Buddhism to Christianity and Islam being counterbalanced by acces- sions from the ranks of the spirit-worshippers. In the case of the Hindus and the Musalmans, immigration from outside the Province accounts for the high rate of increase.

In Lower Burma, where data extending over more than twenty years are available, we find that between 1881 and 1891 the Buddhists increased by 24 per cent., but in the following ten years by only 19 per cent. This apparent diminution in the rate of growth is probably due to the return to their homes in Upper Burma of villagers whom the disturbances that succeeded the seizure of Mandalay had driven tem- porarily into Lower Burma. Among Musalmans and Hindus, on the other hand, the rate of growth during the first half of the twenty years in question was by no means as conspicuous as during the second.

The Christian population of Lower Burma rose between 1881 and 1 89 1 by 33 per cent., and between 1891 and 1901 by 19 per cent. The strength of this population is, however, largely affected by the move- ments of British troops, and it is probable that the falling off in the rate of increase during the second decade is not really as marked as it would appear to be. The principal Christian denominations returned in 1901 were Baptists (66,860), Roman Catholics (37,105^, and Angli- cans (22,307). In Burma proper the Anglicans increased by 76 per cent, between 1891 and 1901 and the Roman Catholics by 48 per cent. The Baptists show a falling off of 18 per cent, for the same period, but this diminution is in all probability due to the fact that a large number of Baptist native Christians did not return their sect at the Census.

Burma forms an Anglican diocese under the administration of the Bishop of Rangoon. The diocese was created in 1877, and then included Lower Burma only. In 1888 new letters patent were granted extending it to Upper Burma. The Bishop is assisted by an arch- deacon and nine other chaplains of the Bengal (Rangoon) Ecclesiastical establishment.

The Anglican missions in Burma are worked through the agency of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. The missionary staff consisted in 1903 of eight British clergy and ninety-five catechists and sub-deacons. The Society labours among the Burmese, the Tamils, and the Karens, its principal stations being Rangoon, Kemmendine, Moulmein, Mandalay, Shwebo, and Toungoo.

From 1 72 1 to 1866 the Roman Catholic Church in Burma was represented by a single mission, known as the Vicariate Apostolic of Ava and Pegu. Subsequently the Province was divided into three distinct missions, one for southern, one for northern, and one for eastern Burma, each in charge of a bishop; and in 1879 the Arakan administrative division was transferred to what is now the diocese of Dacca.

The establishment of the American Baptist Mission dates from the year 1813, when Messrs. Judson and Rice started mission work in Rangoon; but difficulties encountered after 1824 forced the mission- aries to transfer their main sphere of action to the British territories of Arakan and Tenasserim. The Tavoy mission was opened in 1825, and a commencement was there made of that widespread evangelization of the Karens which has for so long been associated with the name of the mission in Burma. The^Kyaukpyu mission was founded in 1831, the Moulmein mission in 1827 ; and after the second Burmese War work was renewed in Rangoon, and started in Toungoo, Henzada, and Bassein. The teaching of the Kachins had been commenced in Bhamo in 1877, several years before the annexation of Upper Burma, and after Thibaw's deportation mission stations were established in other Districts of the newly acquired province. Within the last few years the mission has extended its operations into the Shan States, the Chin Hills, and Karenni. Its work lies mainly among the Karens, with whom the greatest measure of success has so far been obtained ; but the mission- aries labour among the Burmese also, and the Shans, the Chins, and the Kachins have received attention. According to the latest official returns of the mission, there are twenty-nine stations in the Province. The mission has been eminently useful from an administrative point of view, for it has been one of the main instruments in bringing a know- ledge of the languages of the country within the reach of foreign residents. Judson's Burmese Dictionary has long been a household word in Burma ; and what was done for Burmese by that early pioneer has been, and is being, accomplished by his successors for other Provincial vernaculars. The following are the totals for the principal religions returned in Burma proper in 1891 and 1901 :—

The great majority of the people of Burma are agriculturists. In 1901, 5,739,523 persons were returned under the head of agricultural labourers. This figure, in common with all the occupation totals given in this paragraph, includes both actual workers and the persons depen- dent on them. In addition to the agricultural labourers, 717,753 persons appeared under the category of landholders and tenants. The growers of special products numbered in all 385,528 ; and the sum of persons directly supported by the produce of the soil may thus be taken at 6,842,804, or slightly more than 66 per cent, of the total population. This figure represents the greater part, but by no means the whole, of the agricultural interests of the country, for a certain section of the rural community combine cultivation with other non- agricultural pursuits. An attempt was made at the last Census to obtain data regarding the persons by whom agriculture was thus pursued as a subsidiary occupation, and the total of these partial agriculturists was found to be 47,524. It is possible that this figure does not give an accurate picture of the extent to which agriculture is carried on as an additional source of income among the non-agricultural folk, but it seems clear that the proportion of the population liable to be directly affected by general scarcity of crops is not likely to exceed appreciably the 66 per cent, mentioned above. Taking the figures for pasture with those for agriculture, the ratio on the Provincial aggregate is 67 per cent. Under pasture, cattle-breeders (25,508) and herdsmen (46,463) afford the most conspicuous totals.

The artisan section of the community forms roughly 18-5 per cent, of the total population of the Province. The figure on which this ratio is calculated (1,923,084) represents the total of persons shown in the VOL. IX. L census returns as engaged in the preparation and supply of material substances. Strictly speaking, this comprises certain occupations that involve no real technical knowledge, but for the purposes of general presentation the classification is probably exact enough. In the artisan classes the following occupation totals may be cited : fishermen and fish-curers, 126,651; turners and lacquerers, 14,274; silk-weavers, 34,029; cotton-weavers, 189,718; tailors, 57,915; goldsmiths, 42,112 ; iron-workers, 26,221 ; potters, 19,667 ; carpenters, 69,886 ; and mat- makers, 53,585. The commercial classes numbered 449,955, or 434 per cent., and the professional 264,047, or 2-54 per cent., of the Provincial aggregate.

More than one-third of those engaged in com- merce come under the unspecified head of shopkeepers ; while the most important of the professional occupations, from a numerical point of view, is that of the religious mendicant (138,329), a term which includes, besides pongyis or Buddhist priests, probationers for the priesthood and other occupants of monasteries. Medicine was the means of support of 43,252 rural practitioners and their families, teaching maintained 12,178 actual workers and dependents, and the number of persons of all kinds dependent upon the legal profession totalled 7,507. Altogether 392,654 inhabitants of the Province came into the category of general labourers or coolies. This occupation constituted the greater part of those classed under the head of unskilled non-agricultural labourers, who formed 4-2 per cent, of the total population. Government service provided occupation for 191,796 persons, or for 1-85 per cent, of the Provincial total, the largest individual figure being shown by village headmen, who, with their dependents, reached a total of 62,335. The number of those engaged in personal or domestic service was 104,252 ; and those whose means of subsistence were independent of occupation, such as pensioners, convicts, and the hke, numbered 41,522.

Rice forms the basis of all the Burman's meals, and is eked out with condiments according to his means. There are no caste restrictions as to food ; and, when it is available, the Burman has no hesitation in eating any form of animal and vegetable nutriment that a European would consume. He affects, besides, certain dainties that are repugnant to Western culinary notions, but is on the whole by no means a dirty feeder. This cannot be said of the Karens, who are partial to vermin, and to whom scarcely any kind of animal food comes amiss. Dogs are considered a delicacy by the Akhas, the Was, the black Marus, and other hill tribes in the east of the Province ; but Burmans will not touch them. Onions and chillies figure largely in indigenous recipes ; but the most distinctive condiment is tigapi or salt-fish paste, a com- pound which, though exceedingly offensive to the untutored nostril, has achieved a widespread popularity throughout the Province and appears at nearly every repast. On the whole, however, the Burmese villager's daily meal, though possibly not as frugal as that of many Indian peasants, is exceedingly simple.

The male Burman's dress consists of a jacket, ordinarily white, a cotton or silk waistcloth {paso or lo/igyi), and a silk headkerchief {gmrngkitaig). Women wear a jacket resembling the men's, and a petticoat or skirt of silk or cotton. The original Burmese petticoat (famein) was open down the front and showed a considerable portion of one of the legs when the wearer walked. It is still largely worn, though the closed longyi^ a trifle longer in the women's than in the men's dress, is rapidly displacing it in the urban areas of the Province. Nothing is worn on the head by Burmese women, but among the Shans the fair sex cover the head with a cotton head-cloth. In place of the head- kerchief that forms a portion of the male attire, the Burmese woman, when dressed in her best, drapes her silk cloth over her shoulders as a scarf. The scarf is, however, not a portion of her everyday attire.

On ordinary occasions it is dispensed with, and the jacket is also frequently discarded by both sexes while the household or other work is being done. When it forms her only garment, the woman's skirt is wrapped round her body from close under her armpits to her knees. While engaged in manual labour, the man ordinarily tucks up his waist- cloth in such a way as to allow absolute freedom for the lower limbs. It is on these occasions that a full sight can be had of the tattooing with which the male Burman decorates the middle portion of his body from the waist to the knee, ^\^^ere the wearers can afford it, jewellery is much affected by the fair sex. It is mostly gold, and takes the form of bangles, necklaces, rings, ear ornaments, and, in the case of children, anklets. The main dress characteristics of the chief non-Burman hill tribes are detailed in the tribal articles.

The ordinary village residence is a hut raised on piles some little distance off the ground, built of jungle-wood, timber, and bamboo- matting, and roofed with thatch or split bamboo [wagat). The better- class houses have plank walling and flooring, and corrugated iron is gradually obtaining a prominent place in the domestic architecture of the country ; but no real use has yet been made by the Burmans themselves of brick as a material for house-building. The empty space below the house is frequently used as a cattle-pen. The style of building varies little throughout the country. The Kachins and other hill tribes are in the habit of building barrack-like houses, in which several families live together ; but the general rule is for one or at most two families to occupy the same building. Whether they are erected in the hills or the plains, the materials of which the houses are put together are uniform. Bamboo supplies the greater part of the frame- work, except in the dry zone, where bamboos are scarce and hovels are constructed almost wholly of palm leaves. The Burmans dispose of their lay dead by burial. The bodies of monks are burned with more or less ceremony. Burial-grounds are ordinarily situated to the west of the village.

Five is the term applied in Burma to nearly every form of entertain- ment, whether dramatic or otherwise. The zat pwe is performed by living actors ; it represents episodes in the life of one or other of the incarnations of Buddha, and the dialogue is helped out with much singing, dancing, and buffoonery. Similar plays are enacted by means of marionettes {yokthe), whose manipulation is exceedingly effective and involves considerable skill. Performances of this nature are given by professionals ; but J>u>es of other kinds are frequently organized by amateurs, the best-known form being probably the yein pwe or ' posture dance,' in which as a rule a number of girls take part. Pony, boat, and bullock-cart racing are popular pastimes, and cock-fighting is indulged in freely. One of the most striking of the indigenous games is that known as chi/ihn, which consists in keeping a light ball of plaited cane in the air for as long a time as possible by successive blows from the feet, knees, or almost any other portion of the body but the hand.

The players stand in a circle and kick the ball from one to the other, and adepts are able to keep it in motion for a surprisingly long time without letting it touch the ground. Among other amusements may be mentioned kite-flying, and games resembling chess, backgammon, and marbles, the last, known as gonnyinto, being played with the large flat brown seeds of the Entada Piirsaetha. Gambling is a national weakness which it has been found necessary to keep within bounds by special legislation. Boat, pony, and other races are invariably the occasion for heavy betting. There are numerous games of chance, of which one of the best known is the ' thirty-six animal ' game. The Burmans are inveterate smokers. Both sexes indulge freely in tobacco and commence smoking at a comparatively early age, but the cigars that they ordinarily affect have the merit of extreme mildness and contain as a rule a great deal that is not pure tobacco. 'I'he outer covering is ordinarily of maize husks or thanat leaves. The strong black Burma cheroot of the European market is but little favoured by the natives.

The two principal festivals of the Burmans are the New Year, which occurs in April, and the end of the Buddhist Lent, which takes place in October. The former celebrates the annual descent to earth of the Thagya Min, the king of the Nat or spirit kingdom, and is often known as the 'water festival,' as the most prominent feature of the merry- making consists of what may be entitled a battle of squirts which leaves the revellers drenched to the skin. The autumn season of rejoicing might appropriately be termed the ' fire festival,' for the most striking of its ceremonies is the general illumination that takes place, the sending up of fire balloons, and the floating of diminutive lamps down the streams and rivers.

The full moon of the month of Tabaung (roughly speaking, March) is made the occasion for pagoda festivals and other gatherings. The commencement of the Buddhist Lent in July has its less exuberant ceremonies ; and the Tazaungmon festival, between the end of Lent and the close of the calendar year, is marked by rejoicings in certain parts of the country. All these are treated as public holidays, and all are observed more or less by the non-Burman Buddhist peoples of the country, such as the Shans, the Taungthus, and the Palaungs, as well as by the Burmans.

The ordinary Burmese title is Maung (' Mr. ') for males and Ma (' Mrs.' or ' Miss ') for females. To these are added one or more names usually indicative of some object, animate or inanimate, or of some quality. Children are named at birth, and convention usually requires that the initial letter of each child's name should be that appropriate to the day of the week on which he or she was born. Thus, for example, the gutturals {k^ g, ng, &c.) belong to Monday, the palatals {s, 2, &c.) to Tuesday, the labials to Thursday, and the dentals to Saturday. Hence a boy born on a Monday might suitably be called Maung Gale (ga/e = ' small '). JVga and Mi are less respectful sub- stitutes for Maimg and Ma. They are used for children, inferiors, and the like. ^Vith advancing years the honorific U is often applied to a man in place of Maung, especially if he is a senior of substance and position ; and Kyaiatgtagd, with its feminine Kyaungamd, is a title earned by a person who has gained merit by the construction of a kyaiing or monastery. A Pali title takes the place of the ordinary lay name on the assumption of the yellow robe and admission into a monastery. Family names are unknown except among the Kachins, and there is no change in the woman's name at marriage. Shwe ('gold' or 'golden') occurs frequently in Burmese names, and figures largely in the nomenclature of towns, villages, rivers, hills, &c. Occa- sionally it indicates the presence of old gold-workings {SInvedivin, ' gold- mine ' ; Shwegyin, ' gold-sifting ') ; but more ordinarily it is purely honorific {Shivedaung, ' golden hill ' ; Shweiaung, ' golden boat '). ilfyo ('town'), ytva ('village'), faiing ('hill'), inyit ('river'), chaimg (' stream ') form the component part of a large proportion of Burmese place-names, their counterparts in Shan being words like mdng (' state '), nam (' water ' or ' river '), /oi (' hill '), 7iaivng (' lake '), and the like.

See also

For a large number of articles about Burma, extracted from the Gazetteer of 1908 (as well as other articles on Burma) please either click the 'Myanmar' link (below, left) and go to Burma(under B) or enter 'Burma' in the 'Search' box (top, right).

Burma, Commerce and Trade 1908

Burma, Population 1908