Assamese theatre

From The Times of India

From The Times of India

From The Times of India

From The Times of India

If theatre- lovers in Assam feel that this page is serving a useful purpose |

Though this is an extremely detailed page, Indpaedia’s Jammu- and Delhi- based volunteers feel that the work is only half done. Assamese theatre is such a big cultural phenomenon in India that its history deserves to be recorded in much greater detail.

Details that need to be preserved include:

i) A year-wise list of the most important plays of each year: major commercial and critical successes as well as famous flops— a brief synopsis and the name of the playwright (plus, if possible, the names of its first director, theatre company and famous actors);

ii) The profile of every famous playwright, director, Theatre Company and actor deserves an independent page; and

iii) The songs of Assamese plays are another cultural phenomenon that needs to be written about and memories preserved.

iv) Old photographs, old posters.

Such information may please be sent by readers and theatre companies as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name. Links to published articles will be more authentic than original text written by non-experts.

A historical overview

Ancient and mediæval times

By Murchana/ Dwijen Mahanta | অসমীয়া নাটক Assamese drama | Nov 28, 2010

Assamese theatre has a glorious history from past days. One type named Ankiya Nat or Bhaona, composed by Vaishnava reformers like Sankaradeva and Madhavadeva, staged in community halls termed nam-ghar. There are also some other traditional performatory modes such as Bhaoriya, Dhuliya, and Oja-Pali.

Srimanta Sankardeva is the father of Assamese theatre, who wrote plays and dramas five centuries ago to establish Vaishnavism in Assam. He introduced Ankia Nat, Bhoana, Cihnayatra to Assamese audience before Shakespeare even born. He wrote six plays and a drama Cihnayatra. Cihnayatra was a theatrical presentation in signs or paintings which is represented with song, music and dance. After him, his successor Madhavdeva successfully continued this journey with a contribution of five short plays called jhumura. Gopaldev was another close follower of Sankardeva who wrote two plays based on Bhagavat Puranas. Soon the plays of Sankardeva's became popular and got an entry to Royal Palaces (Assam.gov)

Anuj Kumar Boruah| Ram Bijoy in the Capital | Mon, 26/05/2014 adds:

Mahapurush Srimanta Sankardev was the fountainhead of the "Ankia Naat” a kind of one act play, to propagate Neo-Vaishnava religion in Assam. The great saint and social reformer created "Ankia Naat”, by bringing various aspects from the ancient Sanskrit drama, traditional dramatic art forms and his own innovative ideas to create a conventional performing art form in the field of dramatic arts of India. His “Cihna Yatra”’ is regarded as one of the first open-air theatrical performances in the world.

“Ankia Naat Bhaona” is a traditional art form of the 15th century - A style of drama conceived by Srimanta Sankardeva (1449-1568) that displayed spiritual music encompassing a combination of dance and dramaturgy.

Ankia Naataks were performed only by men, even the female characters were enacted by male actors till 1949. [This was an all-India phenomenon. In many parts of India female actors entered only in the 1960s and 1970s, and in others even later.] (Anuj Kumar Boruah| Ram Bijoy in the Capital | Mon, 26/05/2014)

The 1400s and 1500s

One of the most significant theatrical forms from Assam is the Bhaona, which is a traditional form of musical drama that originated in the 15th century. The plays are based on episodes from the Hindu epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata and are performed by actors wearing elaborate costumes and masks.

Another popular form of drama is the Ankia Nat, which was created by the 16th century saint and playwright Srimanta Sankardeva. The plays are based on religious themes and are performed by actors wearing traditional costumes.

The 1800s

In 19th century the socio-political scenario has changed so the themes of theatres also. Ram Navami was the first modern Assamese drama wrote by Gunaviram Baruah in 1857. Kaniyar Kirtan was the second serious social play wrote Hem Chandra Baruah in 1866. It was a social drama expressing the effect of opium. Some popular writer in that period was Rudraram Bardoloi, Benudhar Rajkhowa and BInapani Natyamandir was established in Nowgaon. In this period mythological plays were written in western style. Realistic social drama and comedy appeared in the later half of 19th Century. Lakshinath Bezbaruah was a noted writer, his some of comic characters were litikai, pasani, nomal, sikatpati and nikatpati was very popular. Padmanath Gohai Baruah's character teton tamuli was also popular among people of Assam. (Assam.gov)

Murchana/ Dwijen Mahanta | অসমীয়া নাটক Assamese drama | Nov 28, 2010 adds:

In 1875, Theatre of a Western mould, with proscenium stage and Anglo-European dramatic structure, made its first appearance at Guwahati. This was forty-nine years after the British annexation of Assam. English education and exposure to Bengali theatre during higher studies at Calcutta inspired new generation Assamese in the late nineteenth century to launch theatre in their own language, which became instantly popular and in no time swayed all of Assam. Initially, performances were held on temporarily erected stages. But permanent structures came up in the 1890s and by the second decade of the twentieth century, all the district and sub divisional towns, including a few semi-urban places, had at least one theatre. However, it was neither daily, nor weekly, nor even monthly fare. Usually plays were performed during festivals or important occasions or just for the pleasure of putting up a show. Till this day, apart from the recent touring repertory companies known as Bhramyaman Mancha i.e. `mobile theatre`, no group performs daily or weekly on a regular basis. This happened in spite of the fact that a few made unsuccessful attempts previously. Yet shows take place almost daily in the cultural capital, Guwahati, by one group or the other.

Although proscenium theatre arrived in 1875, modern playwriting commenced eighteen years earlier. The first play, Gunabhiram Barua`s Ram-Navami i.e. a festival dedicated to Rama on widow remarriage, was written in 1857. The next, Kania kirtan i.e. `Kirtan to Opium` in 1861, was a satire on opium addiction by Hemchandra Barua. Rudra Ram Bordoloi wrote a social farce, Bongal-bongalani or `Bengali Couple` in 1871-2, satirizing lascivious concubines and promiscuous women who married non-Assamese outsiders. However, there is no documentation whether these texts were staged. Neither is it known for certain with which play Assamese theatre raised its curtain. The first mythological drama, Sita haran i.e. `Stealing Sita by Rama Kanta Chaudhury, came in 1875. With two exceptions, all ten or twelve plays written later in the nineteenth century belonged to this genre. The presumption that the first staged Assamese drama was mythological may stand confirmed by a gazette notification of four shows of Ramabhishek i.e. Rama`s Coronation, from 15 May 1875, though this earliest available record does not mention if it was the first-ever production. Bhaona was the most popular traditional Assamese form of that time. This usually drew its plots from mythological sources like the Mahabharata, Ramayana, and the Puranas. It was perhaps natural in the transition from traditional theatre to the new variety to retain the content. Mythological drama dominated till about 1920, though it survived till the 1940s, as in Atulchandra Hazarika`s plays.

1900-1930

In the beginning of 20th Century the playhouses were came to the towns and the new audiences demanded new types of plays. Jyotiprasad Agarwal was the father of modern theatre of Assam. He wrote the romantic play Sonit Kuwari, the character Usha and Anirudha are still popular in Assam. Another play Joymati by Padmanath Gohai Baruah has a historical contribution to the Assamese theatre. The plays in this period based on social problems. The trend of mythological-historical play was gradually become to realistic and social. In seventies some different type of plays performed was a huge success. Some of them are Samayar Sankat by Munin Sharma, Sri Nibaran Bhattacharya by Arun Sharma etc.. An Important aspect was the one-act play. Birinchi Kumar Baruah, Satya Prasad Baruah, Bhabebdra Nath Saikia is some of the noted personalities in this field. (Assam.gov)

Murchana/ Dwijen Mahanta | অসমীয়া নাটক Assamese drama | Nov 28, 2010 adds

Early Assamese drama of this age was in blank verse modeled on the Bengali amitrakshar metre, containing fourteen syllables in each line. Later playwrights broke these constraints by adopting the gairish metre, a kind of free blank verse popularized by the Bengali actor-manager Girish Ghosh. Benudhar Rajkhowa introduced prose dialogue in his Duryodhanar urubhanga i.e. `Duryodhana`s Broken Thigh` in 1903. Historical drama appeared alongside the mythological from the beginning of the twentieth century. The example can be given as Padmanath Gohain Barooah`s Jayamati in 1900, as Indian nationalism and the struggle against British colonialism grew in strength. Emotions ran high. Courage, valour, and glories of the past were recreated to arouse patriotism. Such plays dominated after 1920, supremacy that remained intact till just after Independence in 1947. Maniram Dewan, Lachit Barphukan, and Piyali Phukan, collectively by four members of Nagaon Shilpi Samaj in the town of Nagaon, written and staged immediately before and after Independence and earned phenomenal popularity as well.

The source of most historical drama was the Ahom period of Assamese history, which provided many heroes and martyrs i.e. men and women. Among them, two were particularly revered, on whom several works have been written. As for example Jaymati and Lachit Barphukan. Jaymati was an Ahom princess that chose torture and death rather than discloses the whereabouts of her fugitive husband. Lachit Barphukan, a successful Ahom general, twice defeated the Mughal army between 1667 and 1671. His heroics and patriotism are legendary. The much-revered Jyoti Prasad Agarwala made a conscious approach to theatre production for the first time in Shonit Kunwari i.e. `Princess of Shonitpur` in 1924. Before him, attending to actors` speech seemed the manager`s only concern. After him, a few performers like Mitradev Mahanta Adhikar showed similar awareness, but by and large the existence of a concrete production plan correlating and coordinating all departments of theatre was evident only from the 1960s with the arrival of a number of persons formally trained in theatre arts. Within a few years after Independence, historical drama became scarce and made room for social consciousness. The era of modernist social drama may be counted from 1950. Social plays were written before 1947, as early as Benudhar Rajkhowa`s Seuti-Kiran i.e. `Seuti and Kiran` in 1894. But the number was very small.

Most concentrated on reform and national awakening against foreign rule, while other aspects of life remained almost untouched. After Independence, playwrights extended their horizons into political problems, class struggle, the caste system, conflict between generations, erosion of values, communal tensions, enmity between tribals and non-tribals, unemployment, disintegration of the joint family, hopes and frustrations of the middle class, and individual psychological conflicts. All of the subjects were very contemporary.

1930-1950s

Murchana/ Dwijen Mahanta | অসমীয়া নাটক Assamese drama | Nov 28, 2010 adds:

After Kania kirtan and Bongal-bongalani, the first light social play or farce had been Lakshminath Bezbaroa`s Litikai i.e. `Servant` in 1890. It was followed by a number of similar comedies, particularly in the 1930s. Such scripts are written even today, especially in one act, but the number is not large. However, one-act drama holds an important position in Assamese theatre. From the mid-1950s, writers as well as performers felt attracted to it. It became so popular that, during the 1960s, it overshadowed full-length plays. Many one-act competitions used to be held all over Assam, and there were dramatists who specialized in writing short scripts. Until 1949, men portrayed female characters. There were a few attempts to cast women in the 1930s. These can be mentioned as, Braja Natha Sarma tried this in his short-lived, commercial Kohinoor Opera Party. The attempt was also done by the playwright, actor, director, scholar Satya Prasad Barua in his Sundar Sevi Sangha, and by Rohini Barua in Dibrugarh. But the trendsetters had to wait till 1948 when All India Radio launched twin stations at Guwahati and Shillong. Since radio drama required women for female roles, these readers grew used to acting along with men, hence facilitating their appearance on stage. By that time Assamese society also had grown liberal enough to accept, in fact to demand, actresses performing alongside men.

In the early days theatres were lit by candles. But in later days theatre got lighted by hanging rows of kerosene lamps, gaslight, or pressure lamps of the brand name Petromax. All these used to produce a very bright light. When portable power generators became available, they were pressed into service. Electricity came to Assam in the 1920s, but only in a few important towns. The process of electrification in the state started only after 1947. Before 1930, stage decor meant rolled-up painted screens and drapes. Afterwards, flats were used along with painted screens. There were a few attempts at realism by using three-dimensional set pieces. However, realistic scenography made a permanent entry only in the late 1940s, replacing painted backdrops. Stylized sets, even bare stages, have served as theatre designs of late. Costumes were usually hired from agencies that specialized in renting them out. But this practice was more or less abandoned after the 1950s, when mythological and historical plays gave way to realistic social drama, and costumes started to be specially designed for each production.

1975 After Brajanath Sharma, two brothers Achyut Lahkar and Sada Lahkar took hold of mobile theatre in Assam in 1963 by setting up the very famous Nataraj Theatre. They have promoted professionalism in the theatre of Assam. It was the untiring efforts of many of the successors that have brought mobile theatre to today's prestigious position. Ratan Lahkar, the producer of the famed Kohinoor Theatre, is one among them. He started Kohinoor Theatre in 1975. It was in Kohinoor Theatre that several world famous plays, novels, epics and films had their Assamese adaptations. Kohinoor created a sort of record, staging dramas like Mahabharat, Ramayan, Illiad-Odyssey, Cleopatra, Ben Hur, Hamlet, Othello; Titanic etc. (Assam.gov)

Murchana/ Dwijen Mahanta | অসমীয়া নাটক Assamese drama | Nov 28, 2010 adds:

The idiom in the first phase after Independence was naturalism. Gradually, as contact was established with neo-modern playwrights from the rest of India as well as classics by Ibsen, Chekhov, Gogol, Gorky, Sartre, Camus, Brecht, Beckett, and Ionesco, novelty in form and content became distinctly visible in the work of Arun Sarma and some more.

The 21st century

Murchana/ Dwijen Mahanta | অসমীয়া নাটক Assamese drama | Nov 28, 2010 adds:

The present trend, in keeping with the rest of the country, is to use local folk and traditional forms. The interface of theatre with cinema has also created some star performers, notably Phani Sarma, and creative directors like Dulal Roy, etc.

SOME SIGNIFICANT 21ST CENTURY PLAYS

The list below is based on what is available on the Internet. Further details, especially CORRECTIONS, may kindly be sent to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com

2000

Sonitkuwari directed by Bhaben Das

Rupkatha directed by Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia

2001

Amar Prithibi directed by Ramen Roy Choudhury

Sonar Harin directed by Naren Das

2002

Ei Kolijar Majat Jui directed by Dulal Roy

Banhimai directed by Jagdish Sharma

2003

Titas Ekti Nadir Naam directed by Sankar Dasgupta

Rang Pather Rang directed by Dr. Anil Saikia

2004

Eti Mrityu Na Howa directed by Nip Barua

Nohabatu Naam Dwar directed by Pranjal Saikia

2005

Yugantaar directed by Ratan Thiyam

Hridayar Prithibi directed by Jayanta Das

2006

Arunachal Yatra directed by Sitanath Lahkar

Bhaona directed by Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia

2007

Sankardeva directed by Kanhailal and Sabitri Heisnam

Sonali Torali directed by Homen Barua

2008

Bisharjan directed by Pranjal Saikia

Mukti directed by Abhijit Bhattacharjee

2009

Uroniya Mon directed by Dulal Roy

Rajrath directed by Abhijit Bhattacharjee

2010

The Tempest directed by Padma Shri Heisnam Kanhailal

Helen of Troy directed by Homen Barua

2011

Bhaona: The Mirror of the Universe directed by Anup Hazarika

Banikanta Kakati directed by Homen Barua

2012

Kirtanar Ekhon Kobi directed by Jadav Das

Phulari directed by Sanjeev Hazorika

2013

KolaGuru directed by Hiren Bhattacharya

Phera directed by Suman Kumar

2014

Karengar Ligiri directed by Padma Shri Heisnam Kanhailal

Madhabdev directed by Ranjit Sarma

2015

Antar Yaatra directed by Bhaswati Sarma

Bajikar directed by Dr. Ashim Kumar Bhattacharjee

2016

Banbibi directed by Bhaskar Hazarika

Padma directed by Niranjan Goswami

2017

Gossai Gojiram directed by Ratna Ojah

Maniram Dewan directed by Hemen Das

2018

Agonabhumi directed by Samudra Gupta Kashyap

Tajmahal Ka Tender directed by Ajit Das

2019

Majuli directed by Pranjal Saikia

Akou Edin directed by Biswa Roy

2020

Aaro Bhaona directed by Kamal Lochan Bhattacharjee

Bhraymaman theatre

The journey of mobile theatre

1943: Brajnath Sarma started mobile theatre partially inspired by Jatra of West Bengal. But mobile theatre was a technically modified version of Jatra and was a big hit commercially.

1963: Natraj Theatre was started by Achyut Lahkar followed by Ratan Lahkar and Krisna Roy, who established Kahinoor Theatre in Pathsala in 1973, the year marked the concept of a new mobile theatre in the history of Assam.

It was way back in 1963, when the father figure of mobile theatre Achyut Lahkar supported numerous artistes, technicians and others associated with the cultural mass medium to bring this medium to the fore. The company remains in a location for three days and stages new productions every year — averaging 200 shows. They start their month-and-a-half rehearsal in July and after that they are all set to hit the road with their three brand new productions. (Vaishali Dar | The mobile theatre of Assam is a fusion of drama and cinematic art to entertain live |May 2, 2010 | IndiaTimes/ The Times of India)

Assam’s mobile theatres

By Mofid Tourism Assam

Theatre in Assam

Bhraymaman theatre --Assamese mobile theatre industry

The mobile theatre of Assam (with annual turnover worth Rs 10 crores) that presents contemporary themes and adopts even Hollywood stories like the Titanic is extremely popular both in urban and rural areas of the state.

In Assam's entertainment arena, the festive season of Durga Puja is also the time for the 'carnival on wheels' to roll out with its 'magic', 'miracles' and much more 'up the sleeve'. The vastly popular mobile theatre companies (known as Bhraymaman theatre locally) launches their annual shows with stunts and emotional quotients packed together to make a winning combination of drama on stage.To match its unrivalled record of bringing to life what even filmmakers think twice before venturing into on reel, the mobile theatre companies of Assam have roped in contemporary issues – right from Saddam to Superman to vampires to dwarfs.Even Gabbar Singh and Sholay have got a new lease of life on Assam's stage though the much-vaunted Ram Gopal Varma's version got the boot from the public and critics alike. An industry in its own right with an annual turnover of over Rs 10 crore, the mobile theatre industry of the northeastern state has been entertaining the masses for the last few decades gaining in stature progressively.

History

In 1930, the Kohinoor Opera, the first mobile theatre group of Assam, was started by Natyacharya Brajanath Sarma. From Dhubri to Sadiya, from the north bank to the south bank of the Brahmaputra River, Kohinoor Opera performed its dramas, attracting thousands of spectators whi came to see Sarma perform. Apart from initiating a theatrical movement, the Kohinoor Opera introduced co-acting on the stages of Assam. In 1931, Brajanath Sarma, with the help of Phani Sarma introduced female actresses for the first time to appear in their drama productions at a time when male acting was completely dominant, revolutionizing the nature of Assamese theatre.

Ram Bijoy: turning the gender tables

Anuj Kumar Boruah| Ram Bijoy in the Capital | Mon, 26/05/2014

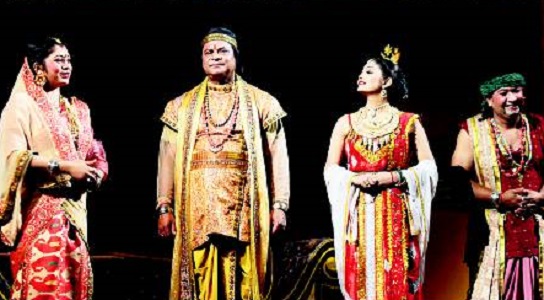

“Ram Bijoy” was designed and directed by Madhurima Choudhury. [Its Delhi premiere was in 2014.]

"Ram Bijoy"-Ankia Naat performed by a group of women who are top actresses of Assam including Moloya Goswami, Nishita Goswami, Madhurima Chaudhuri, Rasarani Chetana Das and Barsha Rani Bishaya. The play was performed in “Brajavali”-concoction of Assamese, Hindi, Oriya and Maithili.

Ankia Naataks were performed only by men, even the female characters were enacted by male actors till 1949. Women performing an Ankia Naat which is considered to be a religious performance is self-explanatory of women empowerment and liberal culture of Assam.

“I wanted to turn the tables. These are the times of women revolution, this women driven performance aids in empowering us”, said Madhurima Choudhury, designer and director of the play who essayed the role of Lord Ram.

Like Jatra?

Though the mobile theatre of Assam has certain things in common with the Jatra of West Bengal – for example, the roving nature and performance on makeshift stages – the Assam productions put in much more effort for technical perfection and have evolved from depictions of mythological stories to themes of contemporary nature. Adaptation of ever-new themes and an eye to changing interests have ensured that the mobile theatre genre does not lose its appeal to the young audience either. With the Assamese film industry in a deep slumber, the plays have also provided the artistes another platform to showcase their talent.

Links with Assamese cinema

The glamour quotient in these plays is ensured as Assamese film stars take up lead roles. It thus vindicates the significant place the mobile theatres hold in the media and entertainment industry in the state. Most of the groups start their tour mid-August and wind up by April. The rehearsals start from June, with the entire unit camping together till the end of the season. Technology forms a very important role in these show-stealers. From sinking the Titanic to making the Anaconda crawl to recreating the Jurassic Park, the mobile theatre groups have 'been there, done that'. Even Princess Diana's tragic death has featured in one of the plays. A leading group, Kohinoor, which has an enviable record for wowing the audience with innovative technical feats on stage, has a dwarf up its sleeve this season. In its banner play in 2008 – Abuj Dora, Achin Kainya – the group is staging the tale of a dwarf and his two lookalikes of normal physical height.

A top actor from the Assamese film industry, Jatin Bora, has been roped in for the role. Transforming the six-feet-tall Bora to a dwarf for one of the three characters is no mean feat. The play has similarities with the Kamal Hassan starrer Apu Raja, but the producers maintain that the similarities are only to the extent that both have lead actors in the role of a dwarf. From lighting effects to specially tailored clothes with help from Mumbai, the producers of Kohinoor have spared no cost to ensure that the effect is complete. And it has paid off well too. Already, it is breaking records in revenue collection wherever it performs.Last year, the group had staged a play with an actress in a double role, with her even appearing 'together' several times on stage!

Titanic

On the social content in his plays and accusations that they play to the gallery rather than propagate social values, Kohinoor owner Ratan Lakhar says, "Titanic was followed by a play on the life of 'Kalaguru' Bishnu Rabha the next year. Bishnu Rabha is a cultural icon of Assamese society and greatly admired. There were few takers for the play. We have a business to run and along with producing plays with social content, we have to make plays which pull crowds." "The plays always have a message for the masses, even though it is wrapped in a package of entertaining gimmicks," he adds. Incidentally, the stage adaptation of Titanic was done by Ratan's group. On the urban-rural preferences of theatre audiences, he says that people's expectation from theatre is not different in cities from that in villages or small towns.

"Cities draw as much crowds as the smaller venues and the arrival of the cine stars on stage has added to the glamour quotient of the theatres. We pull more crowds now," he says. A desi version of Superman is also making his appearance on the stage in Aashirbad theatre's play. The protagonist is set to fly around the stage with an outfit with special powers. Evil forces figure as a Dracula-inspired vampire in a production by the Deboraj theatre group. The vampire, more than 250 years old, sucks the blood of his victims. The group brings alive the blood sucking scenes in the play with technical help.

APTN: A Western look at an Indian Titanic

A stage version of the Hollywood blockbuster and real life story "Titanic" is running to packed houses in the north-eastern Indian state of Assam.

The play is based on the film about a couple who fall in love on the maiden voyage of the world's biggest ocean-liner, which sank in the Atlantic Ocean in 1912.

It may not match the technical finesse of the Oscar-winning film, but the saga of the ill-fated ship is a hit among this remote region's theatre buffs.

The director of the film "Titanic", James Cameron, may not realise it but his Oscar winning tale of love aboard a doomed ship has inspired many in India.

In the east Indian state of Assam, Jack and Rose - the main characters in the film - have been reborn on stage in their Assamese incarnations.

The Hollywood movie "Titanic" is based on the real life story of an ocean-liner on its maiden voyage which hit an iceberg and sank killing nearly all its passengers.

There are not many cinema theatres in this part of the country and so very few have actually seen the Hollywood blockbuster.

The adaptation of the film "Titanic" for a stage version was easy - all the scenes have simply been translated into the local Assamese language.

The play has been directed by playwright Hemanta Dutta who says the universal emotions of this western masterpiece will reach out to a large audience in this remote region, now that it has been translated into the local language.

"I want to bring it to the common people of Assam who could not go to the cinema halls or for lack of their knowledge...for lack of their English knowledge."

Mobile theatre companies are the most popular form of entertainment in rural Assam.

The play "Titanic" has been produced by the " Kohinoor" roving theatre company.

Compared to Cameron's 200 (m) million dollar cinematic extravaganza, the play has cost only a modest 5-thousand dollars to produce.

It uses three models of the ship to create the illusion of a ship steering through the sea.

About 300 artists and technicians are involved in staging the drama.

The play's unprecedented success has meant more money for the actors, and has brought them fame.

Kuntal Goswami plays the part of Jack Dawson in the play.

Copying Leonardo Di Caprio's Jack may be a bit of a challenge, but Goswami says he is loving every minute of it.

"I feel great playing Jack in this drama ...I love this role."

The character of Rose is played by Nikumani Barua, a popular Assamese film actress.

Playing the young Rose as well as the old Rose is overwhelming, says Barua.

"I am doing mobile theatre for the first time. I am really impressed by the audience turnout...it feels great. Film is a much easier medium - stage is very tough."

Indian audiences are known for their fondness for romances and tearful tragedies.

Thrilled by its box-office success, the producers of the play plan to take their mobile "Titanic" to all the towns and villages in Assam.

The company already has a packed schedule over the next eight months.

For those watching the show, the moving tale and the lavish scale of the production is simply amazing.

"Whatever has been done is really very fantastic. And definitely for the first time this has been done within the limitations of such a stage."

Recreating a western maritime disaster with a local flavour has been a recipe for success for the "Kohinoor " theatre company.

Cashing in on the huge media hype created by the film, the producers have spared no expense in publicising their production.

Jack and Rose may not have known where Assam is, but their tragic romance is creating theatre history in this remote state.

And this "Titanic" will not sink before bringing its creators hefty dividends - and a delighted audience asking for more.

Sholay and other films

And if RGV's Aag left you with a sour taste, then check out the stage adaptation of Sholay by Rajashri Theatre this season. Varma's attempts to divert from the original masterpiece may have fallen flat on its face, but the producers in Assam are happy sticking to the old plot and style. From the famous motorbike ride to the train dacoity sequence of the original film, Rajashri Theatre has aptly translated on stage the magic of the blockbuster from the Sippy stable. The mobile theatre groups of Assam have not just entertained the masses; they have also chosen contemporary topics and personalities as themes for their plays.

In 2008 too, the Saraighat theatre group is staging a play based on Iraq's executed former ruler Saddam Hussein. Many plays by different groups have also helped spread social messages, from terrorism to AIDS, through their productions. Bollywood, and Hollywood stories to some extent, however, are major inspirations for many of the plays. Among motley of such plays in 2008 is one based on the life of a robber, an expert in breaking lockers, staged by the Bhagyadevi group. A host of films, from Dhoom 2 to the remade Don to Cash and Victoria No. 203 have figured as inspiration for many of these plays. But the difference is the playwright has adapted it to suit local sentiments.The mobile theatre groups are striking the right balance between entertainment and social content till now, and the growing popularity of the plays even among the youngsters in urban areas prove that they are hitting the right chord.

Assam's travelling theatres are playing to packed audiences in both urban and rural areas despite jazzed up cinema complexes and cable television.About three years ago, the state produced about a dozen-odd Assamese language films annually. However, this has dwindled to naught with moviegoers growing scarce. With regional cinema in the doldrums, actors, musicians, directors and technicians found an alternative livelihood in the highly popular mobile theatres.The theatres, which belong to a tradition stretching back more than four centuries, have multiplied to over 30.It would have been a silent death for hundreds of people involved in the Assamese film industry but for the mobile theatres. Actors, musicians, directors and technicians are today earning more from mobile theatres than they did from films,' he added.Like Ahmed, there are other filmmakers and actors who once ruled the silver screen but are now working in mobile theatres.

Thousands of people prefer to sit in grassy fields to watch the plays with themes ranging from contemporary events to mythologies, Greek tragedies, Shakespearean plays and Indian classics. 'It is indeed a matter of great pride to find mobile theatres being able to captivate so many people despite modern cinemas and a variety of television channels available to the audience,' said Arun Sharma, a noted Assamese playwright and Sahitya Akademi award winner.The modern commercial form, which emerged in the late 1960s, has clung to its community roots with troupes often performing 10-minute sketches before the main show on subjects like AIDS and drug abuse. The troupes themselves are mini communities, each comprising more than 100 actors, technicians, cooks and general helpers, who travel together on the road for eight straight months beginning August and perform on the stage in villages and cities across the state.'An average 800 to 1,000 people watch a show and that in itself is an indication of the popularity of the mobile theatres,' said Biswa Saikia, owner of one of the theatre groups.

Some productions were such hits that dozens of foreign television crews and journalists trailed the travelling theatre groups through slush and mud in the interiors of Assam. The staging of plays like 'Lady Diana', 'Titanic' and the re-creation of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre in New York were instant hits. Encouraged, the travelling troupes have started introducing innovations in their productions by way of lighting and other technical expertise. 'Today, with filmmakers directing on stage and star actors performing as stage artistes, the quality and sophistication of the mobile theatres have gone up. Stage plays with special effects look like a movie,' said set designer Tarun Das. The groups contribute almost 40 percent of their income to local education and other community projects - another reason for the people's acceptance of the travelling theatres over other modes of entertainment.

Osama bin Laden

Far from the lost twin towers of lower Manhattan, a play on the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks by a traveling band of actors kept audiences spellbound in a remote corner of India. Thousands of men, women and children are crowding into a huge canvas tent in Nazira, a small town in northeastern Assam state, to watch two dozen actors dressed in Afghan-style shirts and turbans recreate Taliban country in a play called "Usama bin Laden." A hush descends on the audience as the stage lights focus on a cave, where an actor playing bin Laden, the mastermind behind the Sept. 11 attacks, gets Taliban fighters to pledge to the destruction of America.

As the scene fades, another part of the stage lights up on a young American soldier, whose life takes a dramatic turn when he's asked to join U.S. troops in Afghanistan. Traveling on foot, or on bicycles or by bus, the spectators begin lining up for tickets hours before the two daily shows in this sleepy town, 400 kilometers (250 miles) east of Gauhati, Assam's capital. "Even children have heard of bin Laden. It's curiosity that has made me come," said Dilip Bordoloi, a college teacher among some 4,000 people packed into the tent for the Sankardev Theater's performance last Sunday. Outside the tent on a soccer field, vendors sell buttered popcorn and pink cotton candy as balloons bob among the throngs waiting for tickets. Within weeks of the events of Sept. 11, Biswa Saikia, a stocky man in his late forties who set up the theater group 10 years ago, decided to adapt the events surrounding the attacks for the stage.

"We have succeeded in exposing the fact that bin Laden was actually using Islam to further his own vicious goals and thrust what I call 'Ladenism' in the name of jihad, " said director Sewabrata Borua.

The two-hour play in the local Assamese language, with a sprinkling of English and live keyboard music, is performed on adjoining stages.

"The play's message is loud and clear: Islam does not preach violence. It has been used and projected like that by the likes of bin Laden," said scriptwriter Samarendra Barman, a Hindu. Like much of India, the actors and audience are a mix of Muslims and Hindus who work and live together with ease. And like the leaders of this South Asian nation, the audience backed the Americans and scorned the acts of the Taliban and bin Laden's Al Qaeda terrorist network. Some in the audience threw up their hands in anger and hid their faces when Taliban fighters were depicted killing two Afghan teenagers.

"I'm not much of a theatergoer. But I decided to see 'Laden' after reading so much about his terror acts," said Minoti Bora, a college student. "I got a fair idea of how bad the Taliban was."

The Sankardev Theater group is a small community of some 100 actors, technicians, cooks and assistants who are on the road for an eight-month season beginning each August. "I have not seen even a single television image of the twin towers being attacked and crashing," said Pranab Sarma, who plays bin Laden.

"But I read up whatever newspaper clippings I could and plastered the walls of my home and our camp with Laden's photographs. I used to look at these pictures before I slept each night." Jita Saikia, playing an Afghan woman whose family is killed by Taliban raiders, moved audience members to close their eyes and hang their heads in sadness.

"Her powerful acting gave us an idea about the Taliban, how they could kill a boy because his mother would not let him join the Taliban troops, or commit atrocities on a family for letting their daughters go to school," said Arati Bhuyan, a homemaker, after seeing the play. Apart from powerful themes, traveling theaters in Assam are famous for their ingenious special effects. In the bin Laden play, cardboard helicopters fly onto the stage with tail lamps blazing. Half-a-dozen American commandos, played by actors in full battle gear, shimmy down ropes onto the stage as tanks roll into the battle zone.

The play ends with the triumph of good over evil as the Afghan housewife with the support of American and northern alliance soldiers, enters a Taliban hideout. In a twist on recent history, she helps rescue a kidnapped American journalist who had been taken hostage. With a burst of flames, the play concludes with two jetliners slamming into the World Trade Center. The audience does not boo or cheer.

"Terrorism is a global menace," Jagadish Barman, a veterinarian, said as he walked out. "What I liked most about the play, aside from the performance, is its message against violence and the gun culture."

Superman, Anaconda, Saddam, Dhoom2, Don

At a time when films have stolen the theatre audiences, what better way to get back than adapt cinema to stage? Believe it or not, Assam's mobile theatre groups are doing just that. Be it Superman or Dhoom 2 and Don, they are freely yet innovatively drawing inspiration from cinema.

An industry in its own right, with an annual turnover of over Rs 10 crore, the mobile theatres have been entertaining the masses as also helping in spreading social messages, from terrorism to AIDS.Though the mobile theatre (known as Bhraymaman theatre locally) has certain things in common with the Jatra of West Bengal, like their mobile nature and performance on make-shift stages, the Assam productions put in much more effort for technical perfection and have evolved from being depiction of mythological stories to adapting latest themes as subject matter.

From sinking the Titanic to making the Anaconda crawl to recreating the Jurassic Park, the mobile theatre groups have 'been there, done that'. And they are now all geared up with their annual 'dose of miracles on stage'. Most of the groups start their tour from mid-August and wind up by April. The rehearsals start from June, with the entire unit camping together since then till the end of the season

Special effects

A leading group, Kohinoor, which has a wonderful record of wowing the audience with innovative technical feats on stage, has a dwarf up its sleeve this season. In its play Abuj Dora, Achin Kanya (Untutored Groom, Unknown Bride) in 2008, the group will stage the tale of a dwarf and his two look-alikes of normal physical proportions.

A top actor of the Assamese film industry, Jatin Bora has been roped in for the role. Bora, a six- feet tall actor, will be transformed into a dwarf for one of the three characters he would be playing. From lighting effects to specially tailored clothes and a little help from Mumbai technicians, the producers of Kohinoor have spared no cost to ensure that the effect is complete.

The best-known attempt at playing a double role, one of them being that of a dwarf, was made by Kamal Hassan in Appu Raja. No such known professional attempt has perhaps been made in the history of Indian theatre. The dwarf in Appu Raja was a joker, as is Jatin in the play. But the producer stresses that the similarity ends there. While Jatin will be seen as a circus joker in the role of the dwarf, his other two roles in the play will be that of a police officer and an actor. The group had last year staged a play with an actress appearing 'together' several times on stage.

A desi version of Superman will also make its appearance on stage in Aashirbad theatre's play. The protagonist would fly around the stage with the acquired powers from an outfit with special powers.The evil forces would also have their share of stage in Deboraj theatre group. A Dracula-inspired vampire of more than 250 years of age would suck the bloods of his victims. The group promises to bring to life the blood sucking scenes in the play with technical help.The mobile theatre groups of Assam have not just entertained the masses, but also chosen contemporary topics and personalities as theme for their plays. From spreading awareness about AIDS to presenting the life of Princess Diana, the mobile theatre groups have rarely left untouched any topic of the slightest importance.In 2008, too, a play based on Iraq's executed former ruler Saddam Hussein would be performed by the Saraighat theatre group. Though most of the plays have strong social content, a few are also inspired by Bollywood and Hollywood, which had even led to terrorist threat against the groups. But far from subduing under the threat, theatre owners have given writers a green signal to draw from their cinematic cousins.

Among motley of such plays in 2008 is one based on the life of a robber, an expert in breaking lockers, to be staged by the Bhagyadevi group. A host of such films, from Dhoom 2 to the remade Don to the just released Cash, have more than one point of similarity with the play. But the playwright has adapted it to suit the local sentiments and is expected to be a major money-spinner for the group this season.

The mobile theatre groups are striking the right balance between entertainment and social content till now, and the growing popularity of the groups even among youngsters in urban areas promises a rosy future for them.

Ankiya Nat --One-act play

The Bhakti movement has deeply influenced many forms of traditional performing arts prevalent in Eastern India. In Assam it inspired the superb Anktanat. In fact, all the plays in the repertory of this theatre are one-act plays and they are called Ankiya Nat.

1. This is one of the very few surviving traditional performing arts prevalent in Eastern India.2. Ankiya Nat sinks all differences between religious ritual and aesthetic activity.3. Ankiya Nat once enjoyed high patronage from different levels but today it is a victim of indifference. It is necessary to arrest this decay.

Essential elements of the performing art

Music, Dance, Theatre

To a casual onlooker, who cannot go beyond the periphery, Ankiya Nat may appear only as a form of ritual theatre. Sensitive theatergoers, however, will find that it touches those aesthetic heights from which religiosity and secularity do not look antithetical.

No less than a genius can conceive of a theatre that sinks all differences between religious ritual and aesthetic activity, and then makes the disciplined sublimity of classical arts and the emotional immediacy of folk arts walk together hand in hand. Such a form of theatre is Ankiya Nat and Shankaradeva is the genius who conceived and shaped it towards the second decade of the 16th century. He was a saint-aesthetic, subscribing to Vaishanavism but with a difference.

The elements drawn from the folk forms of music, dance and drama not only broadened the range of appeal, but gave Ankiya Nat its unmistakable Assamese character. Amongst folk forms which influenced him most are Ojhapali, a fascinating form combining elements of balladry, dance and drama: Dhulia, a form of group singing and dancing, Bhaoria, balladry, and Putlanach, the traditional marionette theatre of Assam. The fusion of all these diverse elements and influences to mould a powerful dramatic alloy surely required a sensitivity which Shankaradeva had.

The bhawna, that is, the performance of Ankiya Nat, traditionally takes place in a specially constructed theatre hall called rabha or bhawna-ghar. If such a pandal is not there, then one is improvised, or it is performed under a canopied enclosure. The performance is presented at the centre of the hall and spectators sit on all four sides.

The Bhryaman Theatre companies of Assam

Theatre Bhagyadevi (Estd 1973)

Theatre Binapani (Estd 1980)

Kohinoor Theatre (Estd 1981)

Aabahan Theatre (Estd 1985)

Hengool Theatre (Estd 1991)

Srimanta Shankar Dev Theatre (Estd 1998)

Shankar Madhab Theatre (Estd 2002)

Bordoichila Theatre (Estd 2003)

Madhabdev Theatre (Estd 2004)

Gadapani Theartre (Estd 2004)

Theatre Mahabahu Brahmaputra (Estd 2004)

Sree Guru Theatre (Estd 2005)

Meghdoot Theatre (Estd 2005)

Nataraj Theatre (Estd 2006)

Manchatirtha Theatre (Estd 2006)

Pragjyotish Theatre (Estd 2006)

Pathsala

Pathsala is often describes as the Hollywood of Assam for its big mobile theatre groups and regular performances of drama and other cultural activities round t

Ban Theatre, Tezpur

The first modern Assamese theatre hall, the Ban Theatre, was established in the year 1906.Many of the great modern Assamese dramas of Rupkunwar Jyotiprasad Agarwala and Natasurya Phani Sarma, were first staged here. The tradition continues till today.

Status

As of 2025

Mukut.Das, Nov 30, 2025: The Times of India

The night is alive long before the curtains rise. Children tug at their parents, vendors call out over the scent of steaming tea and roasted peanuts, and a hum of anticipation rolls through the makeshift tent. When the lights finally dim and the first notes of music cut through the air, hundreds of eyes focus on the stage — a stage built not inside a hall, but under canvas, carried from town to town.

Welcome to Assam’s mobile theatres, called ‘Bhramyaman theatre’ — where spectacle still unfolds live, and the old magic of performance refuses to bow to the era of OTT screens and digital entertainment.

Even in an age dominated by touchscreens and binge-watching, more than a dozen such mobile theatre troupes continue to pull enthusiastic crowds across Assam. Their strength lies in a seamless fusion of traditional storytelling and modern technology. These performances, held over a period of six months — mostly from Sept to Feb — are more than just entertainment; they are cultural lifelines, preserving oral traditions, dialects, folklore and songs that define Assam’s rich artistic heritage.

Picture this: the growl of a motorcycle shattering the silence as a lone rider bursts onto the stage, bullets ricocheting, LED lights flaring, smoke machines hissing, and the crowd exploding into cheers. It feels like a high-octane Bollywood action sequence, except this is no CGI magic — it’s all unfolding just a few feet away, live.

‘Drama Nagari’

Rooted in Assam’s rich folk heritage, the origin of these travelling troupes can be traced to Bengal’s ‘jatra’ tradition, which itself dates to the 15th century. In Assam, jatra took hold in the early 19th century, around 1826, during a period of cultural exchange with Bengal. But it was Gunabhiram Barua, a pioneering playwright, who broke away from religious narratives and introduced modern drama to Assamese audiences with his 1857 play ‘Ram Navami’, inspired by the works of Shakespeare.

The modern mobile theatre movement took shape in the 1960s. Dramatist Achyut Lahkar, the visionary behind Nataraj Theatre in Pathsala (Bajali district), was the first to imagine a company that could carry its entire world — stage, lights, sound, and seating — from place to place. His inaugural show on Oct 2, 1963, marked the birth of a new era. Pathsala soon became the beating heart of this movement, spawning legendary troupes like Kohinoor, Awahan, Rajdhani, Hengul, and Aashirvad, earning it the moniker “Drama Nagari”.

Titanic On Stage, Live!

The Kohinoor Mobile Theatre group of Pathsala, a pioneer in this industry, made waves in 1998 by bringing the grandeur of James Cameron’s Titanic to the stage. Tapan Lahkar, owner of the 50-year-old mobile theatre, recalls how renowned Assamese dramatist Hemanta Dutta’s theatrical rendition of Titanic revolutionised Assam’s unique travelling theatre industry. “Until Titanic was staged, nobody could imagine such technical work on a travelling theatre stage,” said Lahkar. Dutta, who breathed life into that milestone production, died in Aug this year at 83.

This year, Kohinoor Theatre is celebrating its golden jubilee by bringing Titanic back — now written by playwright Pranab Barua — and the response has been overwhelming. “Every show this season has run houseful. Other plays like Champak Sarma’s ‘Bokulor Biya Uruli Diya’ and Mridul Chutia’s ‘Prabhu’ are also getting the same overwhelming response,” Lahkar told TOI.

He added that the travelling theatre industry of Assam has developed to a great extent with the introduction of advanced technology on live stages. “Be it lights, LED screens, sound effects or music — the audience can see everything they see on OTT platforms or on the silver screen now. A few mobile theatre groups have also expanded their usual stage by adding ramps through the audience. This is a way to connect with the audience,” Lahkar said.

Beyond Titanic , Lahkar said that productions like Ramayana and Mahabharata were classic examples of imagination, experiment, and dedication on stage. “An arrow shot from one end of the stage, striking another from the opposite end — and the synchronised light and music effects at the exact moment — these were courageous experiments,” he added.

Why They Still Draw Crowds

Actress and Awahan Theatre group owner, Prastuti Porasor, says the enduring appeal of these performances lies in their ability to blend the raw electricity of live performance with evolving technical craft. “Travelling theatre groups still attract people despite the abundance of high-end OTT content. Several reasons make audiences keep coming back, like watching live drama, combined with modern technology,” she said. “Good content, powerful sound and light design, and professional stage set-up — that’s what keeps the magic alive.”

While groups like Kohinoor and Awahan have embraced cinematic innovations, others remain traditional, presenting plays without venturing into extraordinary technical feats. Yet all of them share something that digital screens cannot replicate: offering audiences an immersive experience that blurs the line between theatre and cinema. In Assam, the legacy of mobile theatre is not only alive — it is adapting, reinventing, and steadily proving that even in the digital age, the thrill of live storytelling can still stop time.

Mobile Theatre: 2011-2012

The 5 most popular plays of Mobile Theatre in the year 2011-2012 were:

1)Somok-Hengool Theatre(6 shows at a plot)

2)Raktabidyut Pathak B.A-Bhagyadevi Theatre (6 shows at a plot)

3)Bodnam-Brindaban Theatre(4 shows at a plot)

4)Maya Matho Maya-Rajtilak Theatre(3 shows at a plot)

5)Bhal Pao Buli Nokoba-Kohinoor Theatre(3 shows at a plot)

2012: Year-End Poll

Mobile Theatre - Favourite Theatre Group 2012: ---- Hengool Theatre

Mobile Theatre - Favourite Play:: Abhijeet Bhattacharya's "Hiyat Epahi Golap"

From Kohinoor Theatre 2012-2013.

2016: Going from strength to strength

TORA AGARWALA | And the show goes on | February 5, 2016| The Hindu Businessline

Assam’s mobile theatre industry is under fire for rapidly shedding its traditional identity to embrace the contemporary. But it continues to thrive on popular demand

Nearly two decades after it was made, you’ll still find the residents of Pathshala, a little town in lower Assam, gushing about Titanic. Without ever having watched the film. This is because the Titanic Pathshala loves isn’t the record-breaking blockbuster by James Cameron. It is a play, adapted by a local theatre group months after Cameron’s cult classic hit screens in 1997. But if you ask anyone in Pathshala they will have you believe that Cameron made his version only after seeing Kohinoor Theatre’s production on one of his many visits there. All of Assam was riveted. National media picked it up soon enough. In their September 1998 issue, India Today proclaimed the Assamese version the winner: “After all, could Cameron recreate a maritime disaster without water?”

It was Titanic that catapulted Pathshala’s Kohinoor Theatre to fame. In 2010, the National School of Drama invited them to the Capital to showcase their ‘unique’ model of entertainment. While Assam’s 80-year-old film industry is on the verge of near-collapse, the bhramyaman (mobile theatre) industry is in the pink. The first group, Nataraj Theatre was propped up in Pathshala in 1963, unaware that it was paving the way for a multi-crore industry in the decades to come.

Much is known about the bhramyaman groups of Assam: each group (about 150-strong) travels from villages to towns across the state, staging plays from August to April every year; the entire crew — from the cook to the actor — travel together, and whenever they arrive at a new village, every household reaches for the poosaki kapoor (dressy clothes) it reserves for special occasions.

In mid-2007, the ULFA threatened to force closure of these groups, branding them as vehicles of “cheap popularity trying to ape Bollywood”. While “cheap” popularity managed to override the diktat of the banned militant organisation, the theatre industry still has its fair share of critics. “They sing and dance for no apparent reason,” says Naba Tamuli Phukan. When Abahan Theatre staged their first play of the season, Raktapaan, last year, it was much like a Bollywood masala film, complete with pelvic thrusts and flashy clothes. “I would cycle 10 km from my hometown in Nagoan to Bebejiya, if I missed a single show,” says Phukan, who has been watching plays since 1964. He remembers how he used to think about the plays he watched for days after. “Such was the impact. Nowadays I can’t remember the last play I saw,” he says.

Screen to stage

Jatin Bora, the poster boy of Assamese films, will turn 46 this April. The middle-aged, slightly rotund actor has a tremendous fan following: seven-year-old girls and 50-year-old men alike hound him for selfies and autographs. He is seen on countless billboards across Guwahati, endorsing inverters or promoting his new play. Bora prides himself on being one of the first actors to have made the switch from films to (mobile) theatre, setting a trend in the new millennium.

While the reverse is happening around the world, Assam has witnessed a shift from films to theatre, both in terms of actors and audiences. Why has the Assamese film industry, known for its sensitive, languid storytelling, failed miserably? “The mobile theatre goes to the doorstep of the people in the remotest of villages. Cinema halls, on the other hand, are few and confined to towns,” says Bobbeeta Sharma, chairperson of the Assam State Film Corporation. High production costs and low returns, and lack of good scripts are the other contributory factors. “Theatre in Assam now is high on production value — an extremely stylised and glamorous affair,” says Sharma

A risqué affair

The glamour, however, brings with it many other elemental changes. For one, the ramp is a recent addition to the bhramyaman stage. The choreographer is a new recruit to the crew. The musician, on the other hand, has lost out. “Pre-recorded songs by well-known playback singers like Papon and Zubeen Garg are used by most theatre groups today. The concept of live orchestra no longer exists,” says Teertha Saharia of Abahan Theatre. Several families have lost out on employment too. Take Anil Pathak, for example. A playback singer with various theatre groups since 1984, Pathak now runs a small restaurant selling ‘bhaat aru sah’ (rice and tea) in Guwahati. He quit theatre in 2005 when pre-recorded audio tracks started replacing his voice. “I felt unwanted,” he says. His restaurant gives him and his family enough money to get by but, “What is the point… I was never too passionate about food anyway,” he says.

The natya-nritika, or dance drama is also on the wane. In an attempt to keep the tradition alive, some theatre groups precede the main play with a short dance drama, which is nothing more than a feeble imitation of the glorious productions of the past. National award-winning filmmaker Munin Barua predicts a slow decline of bhramyaman theatre sooner or later. “The kind of plays I write, they don’t run anymore,” says the man who has delivered blockbusters like Hiya Diya Niya (2000) and Ramdhenu (2011). He talks about the golden age where writers like Bhabendranath Saikia and Arun Sharma created socially relevant plays, rooted deep in Assamese culture and history. “The theatre groups vie to get the biggest stars, offering them even bigger paycheques,” he says. While older plays would be adapted from Bengali jatras, most today are South Indian film rip-offs. “I am not saying imports don’t work, they do. Villagers would spout dialogues from Cleopatra and Hamlet till a few years ago,” Barua says, “But we can’t really feed the masses idlis and dosas in the name of bhramyaman theatre; the Axomiya will very soon want his favourite maasor tenga (tangy fish curry).”

Another aspect irking the purists is language. “They use words which no respectable Assamese-speaking person would,” says Barua. While recent imports like tamaam (tremendous) and botola (rubbish) work colloquially, it admittedly sounds awkward on stage. But the crowds love it. Hoots and whistles follow almost every act of Abahan Theatre’s Raktapaan, which has all the ingredients of a runaway success: romance, fight sequences, family feuds and death. The play opens on a monsoon day in Pathshala. But the entire town, in gumboots, raincoats and umbrellas, shows up. The spotlight remains on the heroine, who shimmies around on the ramp in her satin sari. The crowd cheers. They approve.

Big names, big bucks

The USP these days isn’t the play, but the star. The bigwigs have already been booked for next August. Prastuti Parashar, 36, reportedly the highest paid actor in the industry (a whopping ₹1 crore per season) has already been signed by Abahan. She moved to theatre in 2005 with Shakuntala Theatre’s Morome Morom Bisare, considered to be one of the first ‘modern’ plays. “It was a multi-starrer, with fashionable costumes, fast-paced dances, and glamour,” she says. Was it a hit? “A super duper hit!” comes the reply.

Parashar is well aware of the impact she makes in an industry partial to the male. “I don’t confine myself to pretty Barbie doll roles,” says the actor. Her role in and as Maharani (2013), by Rajtilak Theatre, still has hundreds of women stopping her on roads, telling her how ‘empowered’ she made them feel. “I prefer theatre to films. The former is more challenging,” she says.

However, sceptics are certain that it is the money that has led to the shift. “Earlier, theatres would go to rural areas for charitable reasons,” says Arun Nath, a noted actor based in Sonitpur. As a young actor travelling with Rupkonwar Theatre in the early 1970s, he remembers sleeping on wooden benches in old classrooms, in ramshackle school buildings without electricity. Today, big man Bora travels with the group, but in his own car, with a personal assistant and gets the best accommodation. “I don’t even have to button my own shirt,” Bora says, “but the only problem for me as an actor is how demanding mobile theatre is.” In 2013, Bora’s father died while he was touring with a theatre group. “I performed the last rites but had to get back on stage immediately after. I was acting even as my father’s body burned,” he says.

Three weeks back, in Sarthebari, Bora went on stage as Jaladayshya, the ‘good’ pirate, who rescues people from the ravaging floods of Majuli. Around 9 pm, the tickets were sold out, and the enraged crowd proceeded to break the counters. In Tezpur’s Kumargaon, I ask a nine-year-old to choose between a Shah Rukh Khan film in a cinema hall and a Jatin Bora naatok (play) in Joymoti Pothaar. “Definitely Jatin da,” she answers.

Tora Agarwala is an independent journalist based in Assam

The economics, I: Running a troupe, providing employment

ROLE OF MOBILE THEATRE IN SOLVING UNEMPLOYMENT PROBLEM Shodh Ganga.Inflibnet

Employment generation

Once Assamese theatre was considered as a leisure time enterprise, which had neither a professional troupe nor a central playhouse with regular performances, by the best o f the available talent. (Chandra Kanta Phookan: Assamese Theater in Indian Drama in Retrospect (Gurgaon: SangeetNalak Aeademi,Hope IndiaPub.,2007) p-47.)

This absence o f theatrical environment o f die state often made an artist uncertain about his career. As a result most o f the artist instead o f cultivating their real talent in the dramatic field painfully obliged to seek; work and security in some other sphere o f activities where his dramatic talent was least required. But it is pleasurable to see that time has changed many changes in the theatrical field o f Assam. To day theatre, mainly the mobile theatre of the state has attained a position o f prestige and consequently it has attracted new talent to vitalize this unique form o f dramatic presentation which is rarely found outside the state. Presently around forty mobile theatres are performing plays in different comers o f the state. However all o f them are not o f equal standard. These mobile theatres are not considered as a leisure time enterprise now, rather, a well developed cultural organization, which is deeply rooted in the heart o f the people o f Assam. This organization not only imparts cultural entertainment but also provides food, clothes and shelter to a number o f families. The actors, the actresses, the musicians and the technicians working in mobile theatre for years, accepted their work as a helpful profession. Because, inside their working field, they receive prestige as well as financial security.

It has already been mentioned that Achyut Lahakar formed first commercial mobile theatre- Nataraj Theatre in Assam in 1963. Formation o f Nataraj Theatre was unquestionably a bold step, as it has made a rapid change in the dramatic field o f Assam. After that, formation o f Purbajyoti Theatre at Hajo and Suradevi Theatre at Chamata boosted a new dimension to this movement. Gradually many new mobile theatres were formed in the state and that have strengthened this unique dramatic organization to reach its maturity. Today mobile theatre o f Assam is appreciated not only in the state but also in outside. The advent o f cinema industries and TV programmes badly affected theatre all over the world. But in Assam, it is the contrary witnessed by the people. Recently a group o f foreigners had enjoyed the staging o f Titanic by Kohinoor Theatre, Anaconda by Hengool Theatre and Lady Diana by Awahan Theatre and they highly praised all the people connected with these shows for their innovative presentations o f western themes on stage. It is true that a new comer just after entering inside a make shift theatre hall, jamazingly feels if he is inside a temporary make shift theater hall or not. This is because o f the decoration and use o f sophisticated light and sound mechanism inside the theatre hall.

Now to provide such a beautiful environment inside a theatre hall, the producer who is considered as the owner of the whole party had to take lots of responsibilities. On the one hand he invest a huge amount of money (approximately Rs. 70 to 90 Lakhs) every year and appoints around 150 employees for staging three to four plays around 70 different places for eight months. This is unquestionably a Herculean task for an inexperienced producer.

Now let us see how a mobile theatre moves from place to place. Usually the whole troupe of a theatre party may be divided into two groups. The first group consists of 10 to 15 labours or workers, arrive the place of performance nearly four to five days before the staging of the play with all accessories like tent bamboo, wooden stages etc. and build the make shift theatre hall for performance in time. It is painful to see that these workers always keep themselves busy in making the make shift theatre hall to its completion in every place a theartre troupe moves and receive the lowest salary compared to the other workers of the troupe. The second group consists of producer, directors, actors, actresses, technicians, musicians and workers and others except the stage constructing workers of the first group.

A busy schedule of a renowned theatre party is given for convenience.

Theatre Bhagyadevi: Programme for 2007-08

THEATRE BHAGYADEVI

Programme for the Session 2007-08

SL.NO | DATE OF PERFORMANCE |PLACE OF PERFORMANCE

1 Aug 19 to Aug26 Marowa

2 Aug 27 to Aug 30 Bari to Pa

3 Aug31 to Sep2 Loharkatha

4 Sep 3 to Sep 5 Bahari

5 Sep6 to Sep8 Rampur

6 Sep9 to Sep11 Salbari

7 Sep 12 to Sep 14 Changsari

8 Sep 15 to Sep 18 Hasthinapur

9 Sep 19 to Sep21 Gobardhana

10 Sep 22 to Sep 24 Thamna

11 Sep 25 to Sep 27 Nathkuchi

12 Sep 28 to Sep 30 Sarthebari

' 13 Oct 1 to Oct 3 Hajo

14 Oct 4 to Oct 37 Mulagaon

15 Oct8 to Oct1q Drangiri

16 Oct 11 to Oct 13 . Boko

17 Oct 14 to ,Oct 16 Barkola

18 Oct 17 to Oct 19 Puthimari

19 Oct 20 to Oct 22 Kulbil

20 Oct 23 to Oct 25 Kaya

21 Oct 26 to Oct 28 Nityananda

22 Oct 29 to Oct 31 Langeriyajar

23 Novi to Nov4 Ganeshguri

24 Nov 5 to Nov 8 Gitanagar

25 ' Nov 9 to Nov 11 Bamundi

26 Nov 12 to Nov 14 Kalag

27 Nov 15 to Nov 17 Mantyari

28 Nov 18 to Nov 20 Laujan

29 Nov 21 to Nov 23 Bihdiya

30 Nov 24 to Nov 26 Barpeta

31 Nov 27 to Nov 30 Kathalguri

32 Dec 1 to Dec6 Nalbar1

33 Dec 7 to Dec 9 Khanmukh

34 Dec 10 to Dec 12 Burha

35 Dec 13 to Dec 15 Bhabanipur

36 Dec 16 to Dec 18 Bangra

37 ' Dec 19 to Dec 21 Padcan

38 Dec 22 to Dec 24 Bapujinagar

39 Dec 25 to Dec27 Rampur

40 Dec 28 to Dec 30 Nagarbera

41 Dec31 to Jan2 Sontali

42 Jan3 to Jan 5 Majjakheli

43 Jan 6 to Jan 8 Jogighopa

44 Jan 9 to Jan 11 Bahalpur

45 Jan 12 to Jan 17 Kathalguri

46 Jan16 to Jan 18 Sarpara

47 Jan 19 to Jan 22 Haribhanga

48 Jan 23 to Jan 26 Geruagaon

49 Jan 27 to Jan 29 Batadraba

50 Jan 30 to Feb 2 Arjuntal

51 Feb 3 to Feb 5 Lukumai

52 Feb6 to Feb8 Jayrapara

53 Feb9 to Feb 12 Barhat

54 Feb 13 to Feb 16 Sonari

55 ' Feb 17 to Feb 19 Rajgarh

56 Feb 20 to Feb 22 Duliyajan

57 Feb 23 to Feb 26 Naharkaitya

58 Feb 27 to Feb 29 Ouphuliya

59 Mari to Mar 4 1 Maranhat

60 Mar5 to Mar8 Nemguri

61 Mar 9 to Mar 11 Amguri

62 Mar12 to Mar15 Mahuramukh

63 Mar 16 to Mar19 Merapani

61 Mar 20 to Mar 22 Melamara

65 Mar23 to Mar25 Bangaon

66 Mar 26 to Mar 28 Kopahera

67 Mar 29 to Apr 1 Jalah

68 Apr 2 to Apr 5 Barnaddi

69 Apr 6 to Apr 8 Badrukuch1

70 Apr 9 to Apr 12 Kar1a

Total Number or performing days 237

The second group usually arrive the place o f performance on the day o f staging the play. These players and the musician had to accommodate themselves either in the schools, colleges, clubs or sometimes with selected'families under the proper guidance o f the inviting committee. This group performs its shows for three to four nights and is again shifted to another place. This activity is not always enjoyable as the facility o f food and lodging provided by the committee vary from place to place. But it provides a unique experience to share the feelings and emotions o f the people belonging to different cultures and traditions. Before starting their journey the whole troupe prepare four to five plays and four dance dramas. The rehearsal continues for 40 to 50 days. Usually the rehearsal o f all the mobile theatres starts in the last week o f June. The preparations are conducted in a rehearsal hall, which is called Akhara Griha. After full preparation the troupe starts the journey usually in the mid o f August and continued it till the mid o f April, next year. The whole troupe moves under the proper guidance o f the producer. The producer has to control around 150 people staging plays in 70 different places of the state. Unquestionably the job o f a producer demands an extraordinary skill to maintain all these aspects. As make shift theatre halls are not weather friendly- during rainy season these theatres have to face innumerable troubles. Here we may mention the name o f some o f the producers who by their excellent skill have already established in the wide field o f mobile theatre : Achyut Lahakar, the producer o f Nataraj Theatre; Dharani Barman, the producer o f Suradevi Theatre; Karuna Mazumdar, the producer o f Purbajyoti Theatre; Sarat Mazumdar, the (producer o f Bhagyadevi Theatre; Ashutosh Bhattacharya and Rishipad Bhattacharya, the producers o f Makunda Theatre; Ratan Lahkar, the producer o f Kohinoor Theatre; Golap Borgohain the produer o f Jyoti Rupa Theatre; Sada Lahkar, the producer o f Aradhana Theatre; Krishna Roy, the producer o f Awahan Theatre; Subhash Choudhury the producer of Anirban Theatre; Prasanta Hazarika, the producer of Hengool Theatre; Biswa Saikia, the producer of Srimanta Sankardev Theatre and Najrul Islam, the producer o f Bordoishila Theatre.

No. of workers in a company

In generating employment, mobile theatre of Assam is endeavouring an appreciable effort. Usually in a class one mobile theatre like ‘Kohinoor’ or ‘ Awahan’, about one hundred and fifty workers worked together under one producer. These workers can be divided into different categories. A list of the approximate total members of workers is given below :

SL No. Name / Category Total No. of Worker

1. Producer 1

2. Chief Manager 1

3. Managers 4

4. Aesthetic Thinkers 3

5. Secretary 1

6. Chief Publicity Secy. 1

7. Asst. Publicity Secy. 10

8. Chief Organizer 1

9. Lyricist 3

10. Souvenir Editor 1

11. Group Manager 1

12. Music 3

13. Prompter 2

14. Lady In-charge 1

15. Instrumentalist 10

16. Singer 4 '

17. Art Director 1

18. Artist 5

19. Choreographer 1

20. Sound Engineer 6

' 21. Setting Master 5

22. Make up Master 2

23. Costume director 2

24. Actors and Actress 20

25. Dance Artist 14

26. Light Directors 10

27. Stage and Hall Makers 20

28. Still Photographer 1

29. Transportation 5

30. Cook and Marketing Officers 5

31. Gate Keeper 2

32. Others 4

Total No. Workers 150

At present about forty mobile theatres are running in different places

of Assam, out of which more than thirty mobile theatres are from North

Kamrup area. Therefore, approximately (40 X 150 = 6,000) six thousand

people from the total population of the state are directly engaged with

these mobile theatres. It is really a significant event for a state like Assam

where thousands and thousands of educated unemployed youths move

from one place to another in search of job. Mobile theatre, from this

point of view, definitely serve an important role in solving unemployment

problem of the state. For this noble job mobile theatres may be considered

as an industry. It is a matter to be discussed whether this industry can

fulfill all the requirements of an industry. But it is a fact that like an

industry mobile theatres appoint a large number of employees and produce

many new talents like - actors, actresses, technicians, musicians, playwrights

and even producers. People engaging in mobile theatre get all the

requirements for their survival. It is surprising to see that an actor or actress

of a mobile theatre can earn rupees twenty to thirty lakhs for one session.

The producers of course hesitate to disclose the real fact as he could not

maintain the same amount to other players as well.

At present a mobile theatre had to spend approximately Rs. 90,40,000.00 in the beginning year. To understand the whole issue an approximate comparative list of total expenditure in three different periods is given below.

Expenditures o f mobile theatres

An approximate expenditure of a mobile theatre in the starting year

(Please see the accompanying chart)

How mobile theatres earn money

Now let us see how a mobile theatre can earn money. Usually a theatre party perform shows for 237 days as it is seen going through the busy schedule o f a mobile theatre (See schedule list o f mobile theatre). If 7 days are deducted for unexpected natural or man made calamities total performing days will be 230. Now a theatre party earn Rs 50,000.00 (average) per show i.e. (230x50,000.00= 1,15,00,000.00). However some theater parties may perform second show or matinee show, that income is not included here. From this it becomes clear that a mobile theatre can earn

Rupees Twenty Four Lakhs Sixty Thousand :

In co m e: Rs. 1,15,00,000.00 (Approx.)

Expenditure 90,40,000.00

Total Surplus 24,60,000.00 (Approx.)

Looking into this matter a group o f critics like to blame mobile

theatre a money making organization. These critics believe that mobile

theatres, in present time, are trying to manage their business entirely on

commercial basis. They are not conscious o f making any progressive

innovations in their plays. They performe plays only o f those playwrights

who has already established in mobile theatre. New actors and actresses

or playwrights are often neglected in mobile theatre. They select plays

neither on literary merits nor on aesthetic values but for financial benefits.

They pay a huge amount to the glamour artist and often neglect the artists who have already devoted half o f his/her life in the name o f mobile theatre. Theatre involves a democratic spirit. But it is unfortunate to see that inside mobile theater everything is against it These critics also believe that security o f common artist and workers in mobile theatre is very low. They also blame the producers for not providing any CPF or GPF to their employees.

In this context when we met the producers their responses are very much positive and thought provoking. According to them the producer o f a mobile theatre had to spend a huge amount o f money (approximately Rs. 70 to 90 Lakhs) every year. (Informant: Ratan Lahakar, Male, Age 75, Producer o f Kohindor Theatre and Krishna Roy, Male, A ge 74, Producer o f Awahan Theatre, Pathsala, Barpeta, Assam)

Usually the producer borrow s this am ount either from bank or from other N G O ’s or Organizations paying high rate o f interest to m eet up the needful expenditure. That is why every producer o f mobile theatre first o f all thinks o f profit. ‘Profit is a must. Ours is not a charity organization. Our goal is to reach the satisfaction o f the audience and we are keeping glamour artist to achieve that’, says Subodh Majumdar, the producer o f Theatre Bhagyadevi

In many cases mobile theatre fails to perform on stage because of heavy rainfall and flood, and sometimes the troubles viz. bomb blast firing, bandh etc., created by the insurgent groups o f the state. Besides, they have to compromise or to donate some amount to every inviting organization. Considering all these aspects a producer has to proceed in his venture. It is really a difficult job. And that may be the reason, the producer hesitates to depend directly upon new actors or technicians or playwrights. They o f course encourage new faces but subsequently they prefer a few old and well established artist mainly glamour artists and technicians. Regarding a glamour artist Sarat Majumdar, the producer of Bhagyadevi Theatre says ‘As we spend money we have to think about its collection. We borrow film artists and accommodate them in mobile theatre because people like it. Besides, every inviting committee raise the same question ‘which artist you keep this year?’ and we feel helpless.’ ‘Glamour artists are treated separately because they deserve it. If we treat a glamour artist like an ordinary one why people will show interest to them ’, says Ratan Lahakar, the producer o f K ohinoor Theatre. Regarding the providend fund o f the workers, the producer o f a mobile theatre says : in mobile theatre no workers are permanent so opening provident fu n d is not possible. (Informant: Krishna Roy)