Afghanistan: Minerals

Mineral Deposits

Title and authorship of the original article(s)

U.S. Identifies Vast Mineral Riches in Afghanistan

By James Risen,The New York Times, June 13,2010

This is a newspaper article selected for the excellence of its content.

You can help by converting it into an encyclopaedia-style entry,

deleting portions of the kind normally not used in encyclopaedia entries.

Please also put categories, paragraph indents, headings and sub-headings,

and combine this with other articles on exactly the same subject.

See examples and a tutorial.

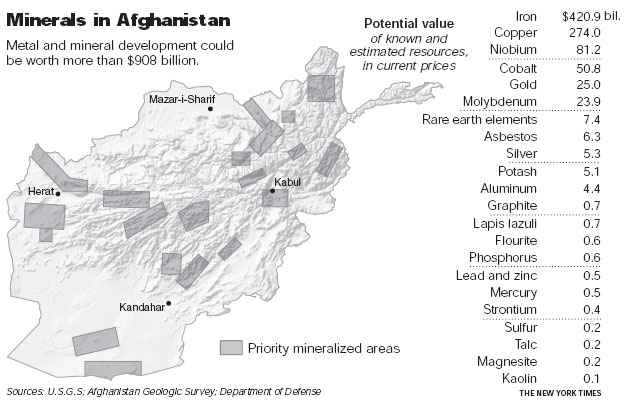

WASHINGTON —The United States has discovered nearly $1 trillion in untapped mineral deposits in Afghanistan,far beyond any previously known reserves and enough to fundamentally alter theAfghan economy and perhaps the Afghan war itself, according to senior Americangovernment officials.

The previously unknown deposits — including huge veins of iron, copper, cobalt,gold and critical industrial metals like lithium— are so big and include so many minerals that are essential to modern industrythat Afghanistan could eventually be transformed into one of the most importantmining centers in the world, the United States officials believe.

An internalPentagon memo, for example, states that Afghanistan could become the “SaudiArabia of lithium,” a key raw material in the manufacture of batteries forlaptops and BlackBerrys.

The vastscale of Afghanistan’s mineral wealth was discovered by a small team ofPentagon officials and American geologists. The Afghan government and President Hamid Karzai were recently briefed, American officials said.

While itcould take many years to develop a mining industry, the potential is so greatthat officials and executives in the industry believe it could attract heavyinvestment even before mines are profitable, providing the possibility of jobsthat could distract from generations of war.

“There isstunning potential here,” Gen. David H. Petraeus, commander of the United States Central Command, said inan interview on Saturday. “There are a lot of ifs, of course, but I think potentially it is hugely significant.”

The value of the newly discovered mineral deposits dwarfs the size of Afghanistan’s existingwar-bedraggled economy, which is based largely on opium production andnarcotics trafficking as well as aid from the United States and otherindustrialized countries. Afghanistan’s gross domestic product is only about$12 billion.

“This willbecome the backbone of the Afghan economy,” said Jalil Jumriany, an adviser tothe Afghan minister of mines.

American andAfghan officials agreed to discuss the mineral discoveries at a difficultmoment in the war in Afghanistan. The American-led offensive in Marja insouthern Afghanistan has achieved only limited gains. Meanwhile, charges ofcorruption and favoritism continue to plague the Karzai government, and Mr.Karzai seems increasingly embittered toward the White House.

So the Obamaadministration is hungry for some positive news to come out of Afghanistan. Yetthe American officials also recognize that the mineral discoveries will almostcertainly have a double-edged impact.

Instead ofbringing peace, the newfound mineral wealth could lead the Taliban to battle even more fiercely to regain control of the country.

The corruption that is already rampant in the Karzai government could also be amplified by the new wealth, particularly if a handful of well-connected oligarchs, some with personal ties to the president, gain control of the resources. Just last year, Afghanistan’s minister of mines was accused by American officials of accepting a $30 million bribe to award China the rights to develop its copper mine. The minister has since been replaced.

Endlessfights could erupt between the central government in Kabul and provincial andtribal leaders in mineral-rich districts. Afghanistan has a national mininglaw, written with the help of advisers from the World Bank,but it has never faced a serious challenge.

“No one hastested that law; no one knows how it will stand up in a fight between the central government and the provinces,” observed Paul A. Brinkley,deputy undersecretary of defense for business and leader of the Pentagon teamthat discovered the deposits.

At the sametime, American officials fear resource-hungry China will try to dominate thedevelopment of Afghanistan’s mineral wealth, which could upset the UnitedStates, given its heavy investment in the region. After winning the bid for itsAynak copper mine in Logar Province, China clearly wants more, Americanofficials said.

Anothercomplication is that because Afghanistan has never had much heavy industrybefore, it has little or no history of environmental protection either. “Thebig question is, can this be developed in a responsible way, in a way that isenvironmentally and socially responsible?” Mr. Brinkley said. “No one knows howthis will work.”

Withvirtually no mining industry or infrastructure in place today, it will takedecades for Afghanistan to exploit its mineral wealth fully. “This is a countrythat has no mining culture,” said Jack Medlin, a geologist in the United States Geological Survey’s internationalaffairs program. “They’ve had some small artisanal mines, but now there couldbe some very, very large mines that will require more than just a gold pan.”

The mineraldeposits are scattered throughout the country, including in the southern andeastern regions along the border with Pakistan that have had some of the mostintense combat in the American-led war against the Taliban insurgency.

The Pentagontask force has already started trying to help the Afghans set up a system todeal with mineral development. International accounting firms that haveexpertise in mining contracts have been hired to consult with the AfghanMinistry of Mines, and technical data is being prepared to turn over tomultinational mining companies and other potential foreign investors. ThePentagon is helping Afghan officials arrange to start seeking bids on mineralrights by next fall, officials said.

“TheMinistry of Mines is not ready to handle this,” Mr. Brinkley said. “We aretrying to help them get ready.”

Like much ofthe recent history of the country, the story of the discovery of Afghanistan’smineral wealth is one of missed opportunities and the distractions of war.

In 2004,American geologists, sent to Afghanistan as part of a broader reconstructioneffort, stumbled across an intriguing series of old charts and data at thelibrary of the Afghan Geological Survey in Kabul that hinted at major mineraldeposits in the country. They soon learned that the data had been collected bySoviet mining experts during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s,but cast aside when the Soviets withdrew in 1989.

During thechaos of the 1990s, when Afghanistan was mired in civil war and later ruled bythe Taliban, a small group of Afghan geologists protected the charts by takingthem home, and returned them to the Geological Survey’s library only after theAmerican invasion and the ouster of the Taliban in 2001.

“There weremaps, but the development did not take place, because you had 30 to 35 years ofwar,” said Ahmad Hujabre, an Afghan engineer who worked for the Ministry ofMines in the 1970s.

Armed withthe old Russian charts, the United States Geological Survey began a series ofaerial surveys of Afghanistan’s mineral resources in 2006, using advancedgravity and magnetic measuring equipment attached to an old Navy Orion P-3aircraft that flew over about 70 percent of the country.

The datafrom those flights was so promising that in 2007, the geologists returned foran even more sophisticated study, using an old British bomber equipped withinstruments that offered a three-dimensional profile of mineral deposits belowthe earth’s surface. It was the most comprehensive geologic survey of Afghanistanever conducted.

The handfulof American geologists who pored over the new data said the results wereastonishing.

But theresults gathered dust for two more years, ignored by officials in both theAmerican and Afghan governments. In 2009, a Pentagon task force that hadcreated business development programs in Iraq was transferred to Afghanistan,and came upon the geological data. Until then, no one besides the geologistshad bothered to look at the information — and no one had sought to translate thetechnical data to measure the potential economic value of the mineral deposits.

Soon, thePentagon business development task force brought in teams of American miningexperts to validate the survey’s findings, and then briefed Defense Secretary Robert M.Gates and Mr. Karzai.

So far, thebiggest mineral deposits discovered are of iron and copper, and the quantitiesare large enough to make Afghanistan a major world producer of both, UnitedStates officials said. Other finds include large deposits of niobium, a softmetal used in producing superconducting steel, rare earth elements and largegold deposits in Pashtun areas of southern Afghanistan.

Just this month, American geologists working with the Pentagon team have been conducting ground surveys on dry salt lakes in western Afghanistan where they believe there are large deposits of lithium. Pentagon officials said that their initial analysis at one location in Ghazni Province showed the potential for lithium deposits as large of those of Bolivia, which now has the world’s largest known lithium reserves.

For the geologists who are now scouring some of the most remote stretches of Afghanistan to complete the technical studies necessary before the international bidding process is begun, there is a growing sense that they arein the midst of one of the great discoveries of their careers.

“On the ground,it’s very, very, promising,” Mr. Medlin said. “Actually, it’s pretty amazing.”

Title and authorship of the original article(s)

|

U.S. Identifies Vast Mineral Riches in Afghanistan By James Risen,The New York Times, June 13,2010 |

This is a newspaper article selected for the excellence of its content. |

WASHINGTON —The United States has discovered nearly $1 trillion in untapped mineral deposits in Afghanistan,far beyond any previously known reserves and enough to fundamentally alter theAfghan economy and perhaps the Afghan war itself, according to senior Americangovernment officials.

The previously unknown deposits — including huge veins of iron, copper, cobalt,gold and critical industrial metals like lithium— are so big and include so many minerals that are essential to modern industrythat Afghanistan could eventually be transformed into one of the most importantmining centers in the world, the United States officials believe. An internalPentagon memo, for example, states that Afghanistan could become the “SaudiArabia of lithium,” a key raw material in the manufacture of batteries forlaptops and BlackBerrys.

The vastscale of Afghanistan’s mineral wealth was discovered by a small team ofPentagon officials and American geologists. The Afghan government and President Hamid Karzai were recently briefed, American officials said. While itcould take many years to develop a mining industry, the potential is so greatthat officials and executives in the industry believe it could attract heavyinvestment even before mines are profitable, providing the possibility of jobsthat could distract from generations of war.

“There isstunning potential here,” Gen. David H. Petraeus, commander of the United States Central Command, said inan interview on Saturday. “There are a lot of ifs, of course, but I think potentially it is hugely significant.” The value of the newly discovered mineral deposits dwarfs the size of Afghanistan’s existingwar-bedraggled economy, which is based largely on opium production andnarcotics trafficking as well as aid from the United States and otherindustrialized countries. Afghanistan’s gross domestic product is only about$12 billion. “This willbecome the backbone of the Afghan economy,” said Jalil Jumriany, an adviser tothe Afghan minister of mines. American andAfghan officials agreed to discuss the mineral discoveries at a difficultmoment in the war in Afghanistan. The American-led offensive in Marja insouthern Afghanistan has achieved only limited gains. Meanwhile, charges ofcorruption and favoritism continue to plague the Karzai government, and Mr.Karzai seems increasingly embittered toward the White House.

So the Obamaadministration is hungry for some positive news to come out of Afghanistan. Yetthe American officials also recognize that the mineral discoveries will almostcertainly have a double-edged impact. Instead ofbringing peace, the newfound mineral wealth could lead the Taliban to battle even more fiercely to regain control of the country.

The corruption that is already rampant in the Karzai government could also be amplified by the new wealth, particularly if a handful of well-connected oligarchs, some with personal ties to the president, gain control of the resources. Just last year, Afghanistan’s minister of mines was accused by American officials of accepting a $30 million bribe to award China the rights to develop its copper mine. The minister has since been replaced. Endlessfights could erupt between the central government in Kabul and provincial andtribal leaders in mineral-rich districts. Afghanistan has a national mininglaw, written with the help of advisers from the World Bank,but it has never faced a serious challenge.

“No one hastested that law; no one knows how it will stand up in a fight between the central government and the provinces,” observed Paul A. Brinkley,deputy undersecretary of defense for business and leader of the Pentagon teamthat discovered the deposits.

At the sametime, American officials fear resource-hungry China will try to dominate thedevelopment of Afghanistan’s mineral wealth, which could upset the UnitedStates, given its heavy investment in the region. After winning the bid for itsAynak copper mine in Logar Province, China clearly wants more, Americanofficials said.

Anothercomplication is that because Afghanistan has never had much heavy industrybefore, it has little or no history of environmental protection either. “Thebig question is, can this be developed in a responsible way, in a way that isenvironmentally and socially responsible?” Mr. Brinkley said. “No one knows howthis will work.”

Withvirtually no mining industry or infrastructure in place today, it will takedecades for Afghanistan to exploit its mineral wealth fully. “This is a countrythat has no mining culture,” said Jack Medlin, a geologist in the United States Geological Survey’s internationalaffairs program. “They’ve had some small artisanal mines, but now there couldbe some very, very large mines that will require more than just a gold pan.”

The mineraldeposits are scattered throughout the country, including in the southern andeastern regions along the border with Pakistan that have had some of the mostintense combat in the American-led war against the Taliban insurgency. The Pentagontask force has already started trying to help the Afghans set up a system todeal with mineral development. International accounting firms that haveexpertise in mining contracts have been hired to consult with the AfghanMinistry of Mines, and technical data is being prepared to turn over tomultinational mining companies and other potential foreign investors. ThePentagon is helping Afghan officials arrange to start seeking bids on mineralrights by next fall, officials said.

“TheMinistry of Mines is not ready to handle this,” Mr. Brinkley said. “We aretrying to help them get ready.” Like much ofthe recent history of the country, the story of the discovery of Afghanistan’smineral wealth is one of missed opportunities and the distractions of war.

In 2004,American geologists, sent to Afghanistan as part of a broader reconstructioneffort, stumbled across an intriguing series of old charts and data at thelibrary of the Afghan Geological Survey in Kabul that hinted at major mineraldeposits in the country. They soon learned that the data had been collected bySoviet mining experts during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s,but cast aside when the Soviets withdrew in 1989.

During thechaos of the 1990s, when Afghanistan was mired in civil war and later ruled bythe Taliban, a small group of Afghan geologists protected the charts by takingthem home, and returned them to the Geological Survey’s library only after theAmerican invasion and the ouster of the Taliban in 2001.

“There weremaps, but the development did not take place, because you had 30 to 35 years ofwar,” said Ahmad Hujabre, an Afghan engineer who worked for the Ministry ofMines in the 1970s. Armed withthe old Russian charts, the United States Geological Survey began a series ofaerial surveys of Afghanistan’s mineral resources in 2006, using advancedgravity and magnetic measuring equipment attached to an old Navy Orion P-3aircraft that flew over about 70 percent of the country.

The datafrom those flights was so promising that in 2007, the geologists returned foran even more sophisticated study, using an old British bomber equipped withinstruments that offered a three-dimensional profile of mineral deposits belowthe earth’s surface. It was the most comprehensive geologic survey of Afghanistanever conducted. The handfulof American geologists who pored over the new data said the results wereastonishing.

But theresults gathered dust for two more years, ignored by officials in both theAmerican and Afghan governments. In 2009, a Pentagon task force that hadcreated business development programs in Iraq was transferred to Afghanistan,and came upon the geological data. Until then, no one besides the geologistshad bothered to look at the information — and no one had sought to translate thetechnical data to measure the potential economic value of the mineral deposits. Soon, thePentagon business development task force brought in teams of American miningexperts to validate the survey’s findings, and then briefed Defense Secretary Robert M.Gates and Mr. Karzai.

So far, thebiggest mineral deposits discovered are of iron and copper, and the quantitiesare large enough to make Afghanistan a major world producer of both, UnitedStates officials said. Other finds include large deposits of niobium, a softmetal used in producing superconducting steel, rare earth elements and largegold deposits in Pashtun areas of southern Afghanistan.

Just this month, American geologists working with the Pentagon team have been conducting ground surveys on dry salt lakes in western Afghanistan where they believe there are large deposits of lithium. Pentagon officials said that their initial analysis at one location in Ghazni Province showed the potential for lithium deposits as large of those of Bolivia, which now has the world’s largest known lithium reserves.

For the geologists who are now scouring some of the most remote stretches of Afghanistan to complete the technical studies necessary before the international bidding process is begun, there is a growing sense that they arein the midst of one of the great discoveries of their careers.

“On the ground,it’s very, very, promising,” Mr. Medlin said. “Actually, it’s pretty amazing.”