Working women: South Asia

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Amount of work put in by women

2017

From: June 24, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

The amount of work put in by South Asian, and other, women, 2017

2018

March 26, 2019: The Times of India

From: March 26, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

The amount of work put in by South Asian, and other, women, 2018

From Latin America to North Africa, women work more hours than men

In several regions, women are putting in a large number of hours at work, whether it is paid or unpaid. According to latest data, the total time spent working, paid or unpaid, is higher for women than men. In Latin America, for instance, women work a total of 8.3 hours a day vis-a-vis 7.7 hours by men.

2019

From: December 10, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic:

Female LFPR in neighbouring countries in 2019 (in %)

Maternity leave

The Times of India, January 27, 2016

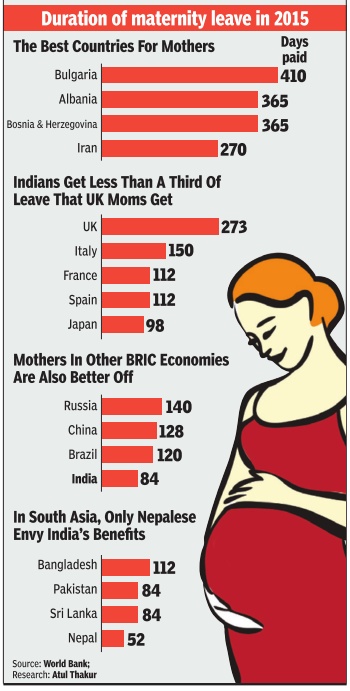

The government has proposed to amend the Maternity Benefit Act, 1961, and increase the statutory maternity leave period from the current 12 weeks to 26 weeks. India's 12 weeks, or 84 days, of paid maternity leave are among the lowest in large economies with significant presence of women in the workforce. Any more than 26 weeks will impact women's employability, cautions the Union labour ministry.

Statistics, year-wise

1993-2016, women in paid jobs, year-wise

Subodh Varma, Why fewer Indian women are working, September 17, 2017: The Times of India

From: Subodh Varma, Why fewer Indian women are working, September 17, 2017: The Times of India

From: Subodh Varma, Why fewer Indian women are working, September 17, 2017: The Times of India

The female workforce is rising in most parts of the world so what explains its slide in India?

In the subcontinent, Nepal & Bangladesh are miles ahead of us. Only Pakistan has a lower rate

Why should a woman have a job? Because it makes a dramatic difference to her life. Working and earning, the capacity to control assets, gives her a boost in decision-making, and lowers domestic violence. Why should we care that women have jobs? Because a labour force that fully represents half the population is likely to be more robust.

But despite the quiet revolution in women's employment around the world, India has been an anomaly , with female workforce numbers continuing to slide. A mere 27% of working-age women were working in paid jobs in 2015-16. A decade ago, in 2004-05, this share was 43%, the same as in 1993-94. In rural India, the slide has been much worse as agriculture fails to absorb them. India was ranked 136 among 144 countries on the economic participation and opportunities index in the Global Gender Report 2015. Clearly , something is wrong somewhere in our society that prevents women from working.

What about other countries? Apart from parts of the Arab world, everywhere else more women are working. China, with its powerhouse economy , has 64% of its women working, one of the highest rates in the world. In the US, it is over 56%.In the Indian subcontinent, Nepal and Bangladesh are miles ahead of us. Only Pakistan has a lower rate.

This doesn't mean that women are sitting at home doing nothing. They cook, care for the children and elderly , do multiple domestic chores, and in rural areas, tend to animals and gardens. All this is invisible work, unpaid and unrecog nised. Census 2011 showed there were nearly 58 million women in the working-age population who said that they were seek ing work. So, it is not as if women who are house-bound do not want to work.

Economists and women's issues experts have been puzzling over the riddle of India's unemployed women and several theories have been floated to explain it. Some say that more young women are studying so they are not looking for jobs.Others believe that families are becoming more prosperous so women are no longer going out for work. Some argue that marriage makes all the difference, while others think caste is the crucial factor.

Economist Jayan Jose Thomas of IITDelhi, who has extensively researched India's employment problems told TOI that Chinese society has quite similar patriarchal attitudes as in India, yet they have managed to boost women's work to such high levels because their economy is creating job opportunities.

A recent World Bank policy paper by Luis Andres and his colleagues has reviewed all these theories and found that none can fully explain the phenomenon.Analysing NSSO data they found that between 1993 and 2011, women's work participation rate dipped by over 13 percentage points in rural areas but the increase in school enrolment was only 5 pct points. Clearly , going to school is not the reason. In urban areas the decrease in working women of 3.2 pct points was more evenly matched by an increase in enrolment of 2.3 pct points.

Another popular theory that women stop working as families grow more prosperous is also not validated by the data.Among the poorest 10% population in rural areas, women's work declined by nearly 16% while among the richest tenth of the population it slid by nearly 8%.Both rich and poor women were getting thrown out of the job market.

Similarly , the paper found that whether married or unmarried, whether Dalit, Adivasi or upper caste, whether illiterate or college graduate -women of all kind were increasingly not working. “The key reason for large-scale and increasing joblessness among Indian women is that there are not sufficient jobs. The jobs that are available are marginal, low paying, insecure and backbreaking, like construction in the recent past. Then, there are issues of safety for women or absence of facilities like crèches. Patriarchal values too come into play . All these lead to women not getting paid jobs,“ said Thomas.

Between 2001 and 2011, India saw a dismal 2% growth rate of jobs per year.Between 2011 and 2015, this has further declined to just 1.23% per year. In this situation, it is no surprise that women are unable to find work.

2016: Workplace gender gaps persist: WEF

The Hindu, October 25, 2016

The World Economic Forum (WEF) reckons that the gender gap in India has narrowed down since 2015 — with the gap closing in primary and secondary education enrolments — pushing it up in the Forum’s global gender gap rankings from 108 in 2015 to 87 in 2016.

However, India remains one of the worst countries in the world for women in terms of labour force participation, income levels as well as health and survival, according to the Forum which has been compiling the Global Gender Gap report since 2006 by examining four broad dimensions of gender equality — economic participation, education, health and politics.

India has closed its gender gap by 2 per cent in a year, but much work remains to be done to empower women in the economic sphere, the WEF report noted. “Overall, India ranks 136 in this pillar out of 144 countries, coming in at 135th for labour force participation and 137 for estimated earned income.”

The global workplace gender gap, measured in terms of economic participation and opportunities, is getting worse and stands at the highest level since 2008, according to the WEF. This gap will ‘now not close until the year 2186,’ going by current trends.

'Bangladesh tops in South Asia

Within South Asia, India’s neighbour Bangladesh is the top performer (ranked 72nd), recording progress on the political empowerment gender gap, but a wider gap on women’s labour force participation and estimated earned income. India’s women rank highly on political empowerment (9th in the world) and the country is closing the gap on wage equality and across all indicators of the educational attainment sub-index, “fully closing its primary and secondary education enrolment gender gaps.”