Water management: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The extent of the problem

Water resources, 1947-2020

From: Vishwa Mohan , January 28, 2020: The Times of India

From: Vishwa Mohan , January 28, 2020: The Times of India

From: Vishwa Mohan , January 28, 2020: The Times of India

See graphics:

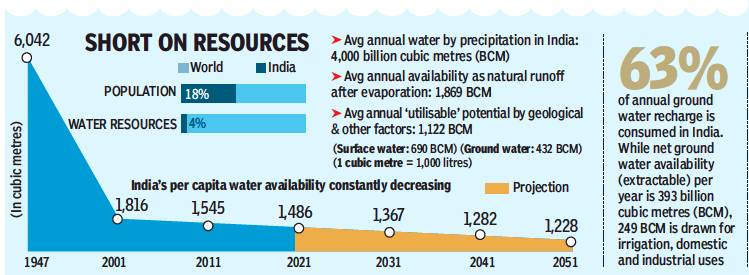

Water resources in India and the world, 1947-2020

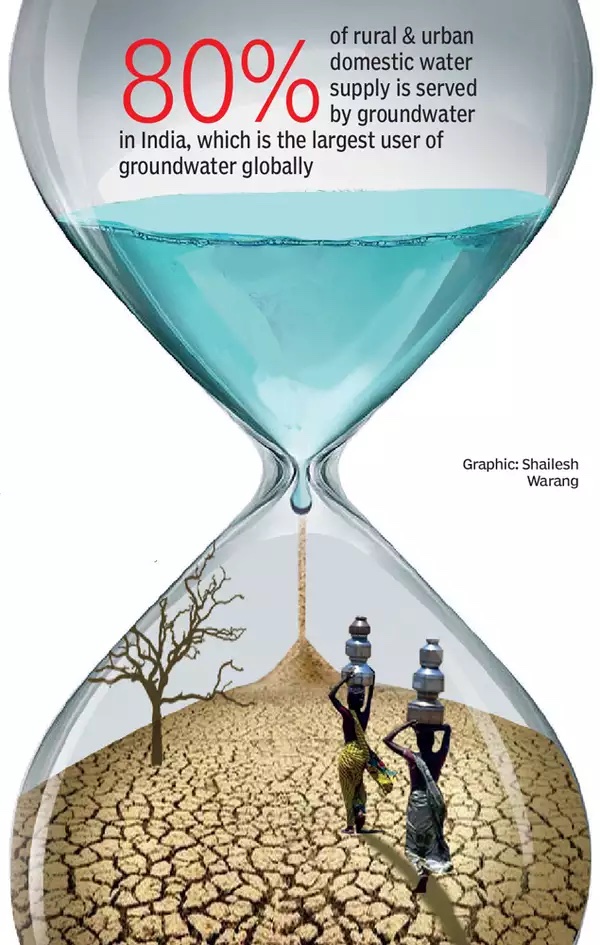

Dependence on groundwater in India, presumably as in 2019

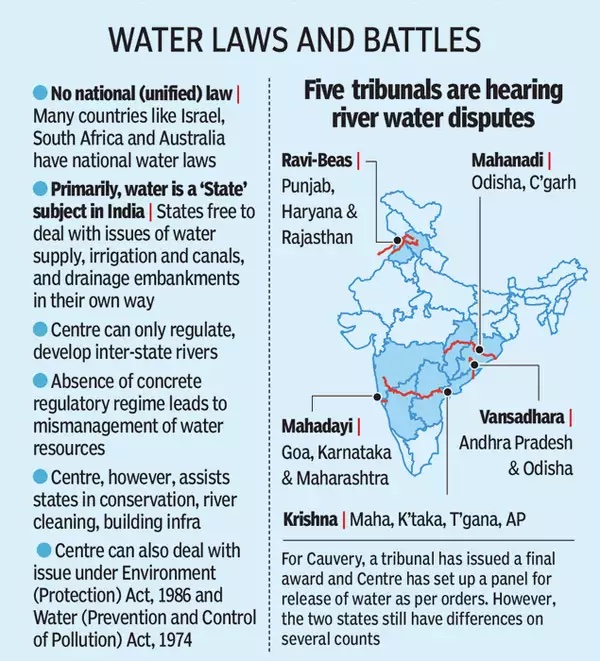

Water Laws and battles in India

The performance of the states

2017-18

VISHWA MOHAN, August 24, 2019: The Times of India

From: VISHWA MOHAN, August 24, 2019: The Times of India

States are displaying progress in water management, but the overall performance remains well below what is required to adequately tackle India’s water challenge, Niti Aayog said as it released a ranking of states and Union Territories (UTs) vis-a-vis their water management practices.

Overall, Gujarat retained its top position while Delhi figured at the bottom in the new ranking while Haryana clocked the best improvement.

Haryana, which figured at No.16 last year, jumped nine spots to No.7 this year in the second instalment of the Aayog’s Composite Water Management Index (CWMI 2.0) for the year 2017-18.

CWMI 2.0, released by Union water resources minister Gajendra Singh Shekhawat, showed that 80% of the states assessed have, over the last three years, improved their water management scores. “But worryingly, 16 of the 27 states still score less than 50 points (out of 100), and fall in the low-performing category. These states collectively account for 48% of the population, 40% of agricultural produce, and 35% of the economic output of India,” said the government’s think tank.

Included among these states/UTs are Delhi, Jharkhand, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Kerala, Rajasthan and Uttarakhand.

The Aayog also observed that major states such as Uttar Pradesh and big economic contributors like Delhi have scored quite low in the overall Index, which was computed on the basis of scores on nine indicator themes: restoration of water bodies, groundwater source augmentation, supply-side management of irrigation, watershed development, participatory irrigation practices, sustainable on-farm water use practices, rural drinking water, urban water supply and sanitation and policy and governance. These themes were allocated different index weights (points).

CWMI is a tool to assess and improve the performance of states and UTs in efficient management of water resources. Niti Aayog said the Index will provide useful information for states/UTs and also for the central ministries concerned to enable them to formulate and implement suitable strategies for better management of water resources.

Among other key points, CWMI 2.0 also noted how large agricultural producers are struggling to effectively manage their water resources and are, therefore, putting food security at risk. “None of the top 10 agricultural producers in India, except Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, score more than 60 points on the CWMI,” the Aayog said while noting that almost half the weighted Index themes are directly linked to water management in agriculture.

Niti Aayog member Ramesh Chand, who was present at the CWMI 2.0 release event, pitched for the inclusion of more variables from the agriculture sector in the next iteration of the index.

“What happens in agriculture will have more of an impact. We have to save water in agriculture to meet the country’s future needs,” he said.

Successes

Traditional methods

Rajeev KR & Sudhakaran P, July 13, 2019: The Times of India

From: Rajeev KR & Sudhakaran P, July 13, 2019: The Times of India

From: Rajeev KR & Sudhakaran P, July 13, 2019: The Times of India

From: Rajeev KR & Sudhakaran P, July 13, 2019: The Times of India

From: August 19, 2019: The Times of India

From: August 19, 2019: The Times of India

From: August 19, 2019: The Times of India

From: August 19, 2019: The Times of India

Uttarakhand: Stone-lined tanks

People in the hills of Uttarakhand worship naulas — fondly called water temples — many of which were built by the Katyuri and Chand dynasties in the 7th century. These small stone structures are meant to store water that sees rapid run-off in the hills. Trees such as madeera, banj, kharsu are planted nearby to boost water accumulation. Over 64,000 of these water retaining structures exist in the hill state out of which 60,000 have now dried up.

But three years ago, one man in a remote village in Ranikhet realised the need to revive these traditional water storage systems. Bishan Singh, 42, was reeling under the sudden demise of his mother when he was told that there was no water for her funeral rites. The village in Gagas valley was experiencing a dry spell and all the naulas there were empty. “I walked several kilometres to fetch water and then vowed to revive the naulas.” He started a ‘Naula Foundation’ and today there are about 500 ‘naula warriors’, working tirelessly to get them flowing again. In Almora district, they were joined by women groups and have successfully revived over 20 naulas. The women start by building a ‘chaal-khaal’ which is a wetland with grass and vegetation that retains groundwater. No grazing is allowed and eventually the land evolves into a wetland area helping naulas store more water. Naulas vary in size from 1 metre long to 10 metres.

To ensure naulas are not defiled, they are dedicated to Lord Vishnu and a stone idol is placed inside to protect the water.

—Vineet Upadhyay

Rajasthan: Water pits in houses

While many parts of Rajasthan remain parched every summer, Guda Bishoniyan village in Jodhpur has enough water to drink and then some. The reason: Every house here has a tanka to collect rainwater. Tankas are underground structures that store rainwater which flows into it through filtered inlets on the external wall of the structure. Depending upon the capacity of the tanka, it can store enough water to feed a family for up to seven months. But apart from tankas, the village also has man-made talaabs and beris.

Bhawar Lal, a priest at a temple near a 500-year-old talaab (pond) in the village, said that every household has a tanka which has enough water to fulfill daily needs but even during a long dry spell there is enough water in beris. “We have numerous beris which are maintained and cleaned regularly.” Beris are basically wells dug up in places where percolated rainwater can get channelised towards it. While building a beri, one can stop digging after they hit clay or gypsum which prevent further percolation of the stored rainwater. The mouth of the beri is narrow to prevent loss through evaporation.

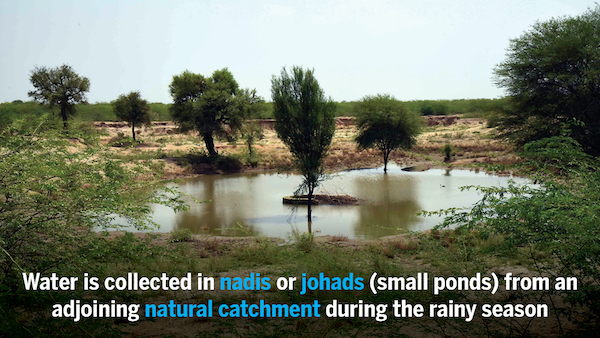

In other parts of Jodhpur, nadis or johads (small ponds) have kept water crisis at bay. Nadis collect water from an adjoining natural catchment during the rainy season and it can last for several months. In Bhagtasni village near Jodhpur, nadis have served as a lifeline for several years. Hukum Singh, a 70-year-old resident, said that water from a 200-year-old nadi in their village lasts almost the entire year. “My ancestors have drawn water from the nadi and so do I.”

In Rajasthan too, bodies that conserve water are considered pious. Vikram Singh from Barli village said, “Most talaabs and nadis have temples on their banks. They are not just a source of water but sacrosanct for everyone. Water and worship go hand in hand here.”

—Yeshika Budhwar & Ajay Parmar

Kerala: Horizontal wells, palm tanks

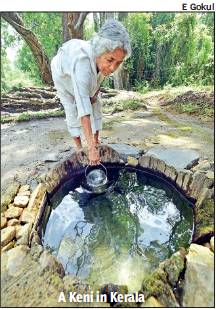

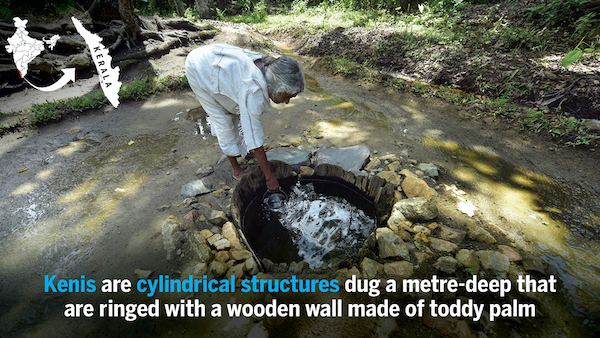

No temples are as revered in Wayanad as the unassuming kenis — centuries old mini wells — that have ensured water for the Mullu Kuruma tribe even during the harshest of summers. Kenis are cylindrical structures dug a metre-deep that are ringed with a wooden wall made of toddy palm (caryota urens). Most of the kenis are centuries old and located in wetlands where the water table is near or above the ground level and water emerges as a spring.

Today, elders look for certain biological indicators — presence of trees like vateria indica, ficus virens or termite mounds — to select the site for kenis. It’s a long and slow process. The palm trunk that is used is cut a year before and soaked in water so that the spongy softwood core disintegrates and the remaining outer hardwood, which has excellent filtration properties, is inserted into the pit. A study by the Centre for Water Resources Development and Management (CWRDM), Kozhikode, had shown that some kenis still yield more than 1,000 litres a day throughout the year. Girish Gopinath, an associate professor at Kerala University of Fisheries and Ocean Studies (KUFOS), who was involved in the CWRDM study as a senior scientist, said that water drawn from kenis meets drinking standards.

The significance of kenis is deeply rooted in the Mullu Kuruma culture and tradition. “We consider kenis to be a blessing from God. It is customary that every newborn in the hamlet is first given a bath with water drawn from a keni. Also, brides collect a pot of water from keni and offer it at Veliyapura, the abode of our ancestors. When a person dies, the body is bathed with keni water before funeral,” said Chomi, a 74-year-old at Tirumugham Colony in Pakkom,Wayanad.

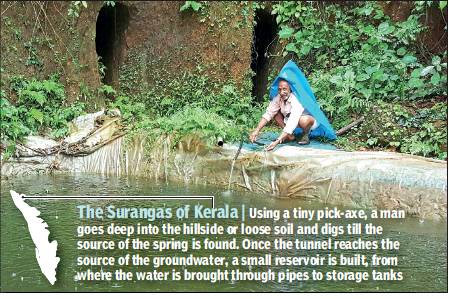

Some 200km away, in Kasaragod, horizontal wells or ‘surangas’ have fed water to a large population for centuries. C Kunjambu, the ‘waterman’ of Kasaragod, is credited with reviving this traditional method of harvesting in these parts as well as neighbouring Karnataka. In Kasaragod alone, over 1,000 surangas have been built by Kunjambu over the past 50 years. As Kunjambu went down the slippery steps of an old suranga he built as a teenager, he explained that once dug on a hillside, they last for a lifetime. “It can be 100 to 150 metres long. Using a tiny pick-axe, the well digger goes deep into the laterite hillside or loose soil till the source of the spring is found. Once the tunnel reaches the source of the groundwater, a small reservoir is built, from where the water is brought through pipes to storage tanks or wells.”

Kunjambu added that a single man can dig a suranga, but it may take up to a month and claustrophobia is common.

Surang Bawadi, Vijayapura (Karnataka)

Rohit BR, Dec 7, 2019 Times of India

From: Rohit BR, Dec 7, 2019 Times of India

From a distance it looks like one of the many algae-ridden ponds that dot the drive in this part of the country. Garbage is strewn around and shrubs hide a large part of it from sight.

The spot is unlikely to catch the eye, except for a blue board that glistens in the sun. It reads: “The site is under protection of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI)”.

A few steps away, the small opening of a tunnel materialises into view. The pond and the tunnel are part of a 16th century water management system called ‘Surang Bawadi’ in Karnataka’s Vijayapura city which has just been included in the World Monument Watch list for 2020 along with 24 other monuments from across the world.

The list, prepared by the World Monuments Fund (WMF), a New York-based organisation, includes heritage sites in need of urgent action. WMF partners with stakeholders to design and implement activities for conservation. Suranga Bawadi was chosen from among 250 shortlisted sites across the globe as part of traditional water systems of the Deccan Plateau. It was nominated by Syed Mehriz Khatib, a Vijayapurabased heritage enthusiast, after he felt the need to conserve traditional water systems in India.

“On a visit to Iran, I saw traditional water systems in use, providing water and drawing tourists. Vijayapura’s water systems have similar potential,” said Khatib, who will coordinate with WMF to revive the water channels. “Amount of funds for the restoration is yet to be decided,” he said.

Surang Bawadi is an integral part of the ancient Karej system that supplied water through subterranean tunnels in the 16th century during the Adil Shahi period. The system is known to be environmentally sustainable as it employs water harvesting and conveyance techniques through which groundwater can be obtained without causing damage to the tapped aquifer. Vijayapura, known as Bijapur back then, did not have major water resources in the region.

Adil Shahi kings made arrangements to ensure adequate supply through distribution of tanks, wells and water towers linked by a network of pipes and aqueducts. Many consider it an engineering marvel.

Over the years, though, the water system fell into disrepair as parts of it falling in private land were blocked to take up construction work.

“Two years ago, the tunnel of Surang Bawadi was shut by a local landowner. After activists and historians protested, the local government and the ASI reopened the tunnel and installed a board stating it is a protected area,” local social activist Raju V said.

Mounesh Kuravatti, an official with ASI’s Dharwad circle, under whose jurisdiction Vijayapura’s traditional water system falls, is aware of damages to the structures. “We keep raising awareness that the water network is under ASI protection, yet constructions have come up. As a result, portions of the network have suffered damage. We are drawing up a plan to rejuvenate parts of the system in public land, but the district administration will take a call on whether anything can be done about those in private land.”

Experts are hopeful that restoration of the system will help meet the city’s requirements. Dr HG Daddi, who has deep knowledge of the subject, said it helped Adil Shahi kings supply adequate water to their kingdom’s 10 lakh people. “Today, despite scientific and technical advance, the administration struggles to meet water needs of the city’s three lakh population,” Daddi said. Last summer, 10 wards of the city’s 35 went bone dry. The crisis is deepening every year, residents said.

The Puducherry Water Rich Model

Kiran Bedi, July 1, 2019: The Times of India

From: Kiran Bedi, July 1, 2019: The Times of India

From clogged drains to flowing canals: The Puducherry Water Rich Model

At a time when water conservation has become of paramount importance, as highlighted by the Prime Minister in his Mann Ki Baat broadcast on Sunday, a model called Puducherry Water Rich could perhaps offer some key learnings.

The genesis of the model was in interactions by a team of officers from Raj Nivas Secretariat and other departments over weekends with the public. Two issues were repeatedly highlighted in these interactions

• The need for desilting rural canals for improving water retention carrying capacity.

• The urgency of desilting urban drains to ensure regular flow and prevent malaria and dengue.

Most of the drains had been in a state of utter neglect for decades. The irony is that the practice of community involvement in desilting of canals and maintaining them goes back centuries in Puducherry, to the reign of the Pallavas. The Cholas and French too took this issue very seriously.

On December 22, 1937, the administrative control of supplying water for irrigation purposes was placed under the public works department. Till date it is the PWD, which is in charge of this management.

As mentioned earlier, since a multi-department team was regularly monitoring the situation of water bodies, the PWD finally admitted that they did not have the funds to de-silt 86km of 23 feeder channels and desilt and feed 84 tanks and 609 ponds, as was the task allotted.

They also said most of the channels were dangerously choked and could not be cleared manually. JCB machinery was required to desilt these channels, for which they had no funds.

We decided to go public, and used social media. On September 24, 2018, the first such appeal was made through my personal Twitter handle. Support started to pour in instantly, from educational institutions, corporates, business chambers, market associations, and an RWA. Individual philanthropists came forward and an MLA offered help.

The desilting of the first canal began on September 29, 2018. Thereafter there was no looking back. Interestingly, in rural areas we needed water in irrigation channels and in urban areas we needed to prevent overflowing of drains.

We were ready just in the nick of time for the rains. The canals filled with water. Our lakes and tanks too received good water. People said they had seen this after decades. We also had no flooding in urban areas.

We awarded all donors Swachta Hi Sewa Awards. They all committed to renew support for this year as well. Contractors too received their payments without any delay.

So what is the Puducherry Water Rich Model?

• Ensure mapping and bring under watch all water bodies and drains. Use technology.

• Use MNREGA where machinery is not required and human contact is safe. It empowers people and provides livelihood.

• Link the local community for shramdaan and monitoring water bodies. Encourage participation as they are the real stakeholders.

• Link them with the nearest donor support — any industry or institution.

• Let the supporter and the service provider decide on the contractual cost. Government officials should only be facilitators, not in any way negotiate or deal with their money.

• Allow farmers to take the silt away, as it is their soil which got washed away. It is rich in nutrients. Do not charge the farmers anything for it.

• Make collectors and municipal commissioners accountable for this work.

We went literally from factory to factory, university to university, giving time limits for construction of water harvesting pits. It worked.

In many colonies where municipalities were spending money for supplying tanker water, it is now being saved because water table in the areas went up.

Water is prosperity. It’s health. It quenches our thirst. It is life itself. Value it.