Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Arrests, convictions under UAPA

2016-19

February 11, 2021: The Times of India

As many as 96 people were arrested under the sedition law in 2019, though only two were convicted and 29 acquitted in the same period, the home ministry informed the Rajya Sabha, citing the latest NCRB data on Crime in India.

The same NCRB report states that 5,922 people were arrested under Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) between 2016 and 2019, though the number of people convicted under the Act during this four-year period was just 132, the ministry said in reply to a different question in the Rajya Sabha.

Asked via a written query in the House if any steps were taken to strengthen the sedition law in view of the courts freeing those arrested under the “weak” law, junior home minister G Kishan Reddy replied that “amendments of laws is an ongoing process”.

In reply to another question on arrests under UAPA, Reddy said 1,948 people were held under the law in 2019, as per NCRB data.

Bail

Difficult to obtain

June 21, 2021: The Times of India

People who are guilty of crimes should face imprisonment, while the innocent should not be put behind bars. But what happens to those who have to wait for the law to decide if they are innocent or guilty? There's a system to ensure that they stick around to face justice, without being jailed as though they are guilty. It’s called bail.

That system also ensures that the accused will not cause further trouble; hamper the trial they’re about to face; or threaten or influence the witnesses in the trial. The court has to see if all these provisions are met and then grant bail, with these conditions in place. Even when the court considers the severity of the alleged offence, it does not automatically bar the possibility of bail.

Unfortunately, things have not been so straightforward for quite some while now. Legislations, especially those dealing with organised crime and economic offences, have started including severe restrictions on granting bail. Today the harshest restrictions have been applied in legislations dealing with terrorism. With the enforcement of these stringent legislations, we’ve also seen a rise in the misuse of them. As noted by the Supreme Court in 1994, when courts were inclined to grant bail in cases registered under ordinary criminal law, the investigating officers would invoke the anti-terror legislations like TADA, even though it was not applicable at all, just to circumvent the authority of the court to grant bail.

The other development that has been taking place alongside this is that investigations and trials are taking a longer time to conclude. People who did not get bail can very well end up spending years without trial. In the public imagination and narrative, arrest and time spent in jail, even without a trial, have become equivalent to conviction, and bail, at times, equivalent to acquittal. Though anyone with more than a passing acquaintance of the criminal law knows that this is far from the truth, this idea of linking pre-trial bail with a likelihood of guilt or innocence has pervaded into the legislation and also judicial thinking. Many legislations now provide that bail should not be granted unless the court has good reasons to think that the accused is innocent.

What seems to be a minor change, one that a layperson may even think reasonable, but makes a world of difference when applied as a legal standard, is when a person accused of a crime applies to a court seeking bail. The court should not only see whether the accused will stick around for the trial and meet the other criteria mentioned above, but also weigh the case of the prosecution and the accused against each other, before either side has presented the full evidence in support of their stories, to see if the accused has a good chance of being acquitted eventually.

The Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1967, however, has gone one step further and provided that if the court has reason to believe that if the accusation against the prosecution is prima facie true, bail should then not be granted. The standard here is not in weighing the stories of the prosecution and defence, sans evidence, against each other, but only in considering the prosecution version, and seeing if it sounds true. In the case of Zahoor Ahmed Shah Watali, the Supreme Court in 2019 cancelled the bail of the Kashmiri businessman, accused in a terror funding case, saying NIA has collected ample evidence to show linkages between the Hurriyat leaders of Jammu and Kashmir and terror organisations as also their activities to wage war against India. The court said it will not go deeper into the quality of supporting material relied upon by the prosecution, but only form an opinion on broad probabilities. This made bail in UAPA cases even a more difficult proposition, because on broad probabilities, anything is possible.

In light of this, the bail applications of those accused in the Bhima Koregaon cases were considered. As a result, apart from those who obtained bail for a short period on medical grounds or for some grave personal exigency, the persons accused of offences under UAPA have not got bail.

There is no saying how long the trial in the Bhima Koregaon or other cases under UAPA will go on. The outcome of this whole situation, however, is that persons are jailed only on the basis of an accusation, which is tested only to see if it is a coherent narrative, and not whether it is supported and backed meaningfully by evidence. This will ensure that they end up being in jail for years together, before they stand a chance to prove their innocence. And in that time, some will lose their livelihoods, some will lose their loved ones, some will see their health and family lives deteriorate, and all will lose years from their public lives. The Delhi High Court June 15 order in the case of Asif Iqbal Tanha, Devangana Kalita and Natasha Narwal, who were accused in connection with the Delhi riots in 2020, works out a way within this stringent and complex legal framework to grant bail. The court, upon going through the chargesheet, notes that there is “complete lack of any specific, particularised, factual allegations, that is to say allegations other than those sought to be spun by mere grandiloquence”, which amount to a terrorist act or raising funds, conspiracy or act preparatory for a terrorist act, punishable under UAPA. Having found that UAPA does not apply in the case, the court then reverted back to the original principles for bail, that is, it relied upon the basic standard under normal criminal law, which we discussed right at the beginning of this article. This decision neither negates the stringent legislation nor changes the standard for bail in UAPA cases in any way, but rather, as the Supreme Court did in 1994, decries the misuse of UAPA. What really comes out of this judgement remains to be seen.

The writer is an advocate on record at the Supreme Court of India

Court judgements

‘Civil disturbance can’t be UAPA offence’: HC/ 2021

Prabin Kalita, April 14, 2021: The Times of India

Stating that someone accused of civil disturbance can’t be booked under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act unless it qualifies to be an act of terror, the Gauhati high court has upheld the bail granted by a special NIA court to jailed activist-turned-politician Akhil Gogoi. The special court had given bail to Gogoi, who was booked under the stringent law for his anti-CAA speeches in 2019 on October 1 last year.

“The dominant intention of the wrongdoer must be to commit a ‘terrorist act’ coming within the ambit of Section 15(1) of the Act… What, therefore, follows is that unlawful act of any other nature, including acts of arson and violence aimed at creating civil disturbance and law and order problems, which may be punishable under the ordinary law, would not come within the purview of Section 15(1) of the Act of 1976 unless it is committed with the requisite intention,” the bench said.

The lower court had granted Gogoi bail after observing that the allegations brought by the agency could not, prima facie, said to be a terrorist act perpetrated with the intention of threatening the unity, integrity and sovereignty of India or to strike terror among the people.

No error in granting bail to Akhil: HC

The NIA subsequently challenged the bail order in the high court.

While even spoken words, including provocative speeches, can be construed as unlawful activity under Section 2(1) (0) of the1967 legislation, “the same must be done with the intention to cause death of, or injuries to any person or persons, or to cause loss of or damage to or destruction of any property aimed at disturbing the unity, integrity, security and sovereignty of the country”, the HC bench said.

The basic allegations levelled by the NIA in its chargesheet are that Gogoi made provocative speeches, inciting the public to resort to violence and draw up a plan to set fire to houses belonging to people from the Bengali community living in the Amrawati Colony at Chabua in Dibrugarh district.

“We are of the considered opinion that the views expressed by the learned Special Court, NIA, leading to granting of bail to the respondent is a possible view in the facts and circumstances of the case. Therefore, we do not find any error in the approach of the learned court below while exercising discretionary jurisdiction and granting bail to the respondent,” the bench said.

Gogoi, who is contesting the Sivasagar assembly seat this election, was taken into preventive custody by police on December 12, 2019 as protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill raged in the state, resulting in violence at several places. The case was transferred to the NIA two days later. He has been in judicial custody since.

The dominant intention of the wrongdoer must be to commit a ‘terrorist act’… What, therefore, follows is that unlawful act of any other nature, including acts of arson and violence aimed at creating civil disturbance and law & order problems, which may be punishable under the ordinary law, would not come within the purview of Section 15(1) of the Act unless committed with the requisite intention —Gauhati HC The basic allegations levelled by the NIA are that Akhil Gogoi made provocative speeches, inciting the public to resort to violence and draw up a plan to set fire to houses belonging to people from the Bengali community

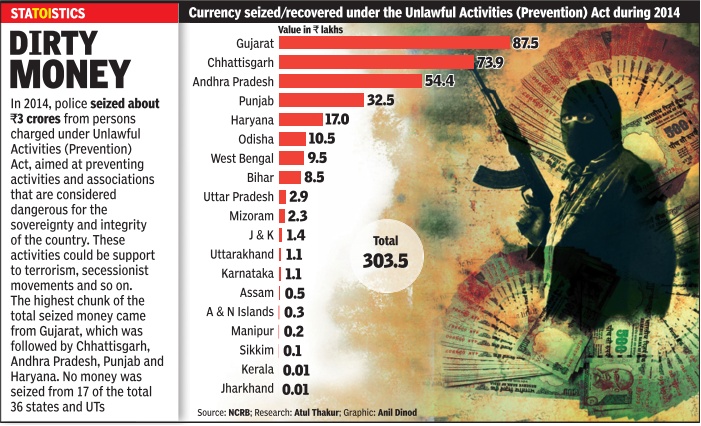

Seizures under UAPA

2014

Graphic courtesy: The Times of India

See graphic:

Currency seized or recovered under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 2014

Amendment to UAPA

2019

August 3, 2019: The Times of India

Cong finally votes with govt, amended terror law passed

New Delhi:

Parliament passed the amended UAPA bill, which provides for proscribing individuals involved in terror crimes as terrorists, after a sharp debate which saw home minister Amit Shah clash with opposition leaders P Chidambaram and Digvijaya Singh.

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Amendment bill, 2019, was passed with 147 ‘ayes’ against 42 ‘noes’, with Congress finally voting in favour of the bill notwithstanding its opposition to what it said was a vague provision for proscribing an individual whom the Centre holds to be a terrorist. Other parties who voted with the government included TRS, BJD, TDP and AIADMK.

The parties that voted against the bill included Trinamool, CPM, CPI, DMK, RJD, SP, NCP, PDP and IUML. Their reservations primarily pertained to blacklisting of individual terror suspects and the “anti-federal” provision seeking to empower the National Investigation Agency DG to seize properties linked to terrorism without prior consent of the state police chief. They also cited the low conviction rate in UAPA cases.

Congress voted for the bill after supporting a demand to send the bill to the select committee, which was rejected by the House by 104 to 85 votes.

Shah slammed the “low conviction rate” argument and said it was based on the combined investigation and prosecution record of state governments and the NIA. Of the 278 cases registered by the NIA under UAPA, chargesheets were filed in 204. Of the 54 cases where courts passed judgment, 48 resulted in convictions — a conviction rate of 91%, which Shah said was “the best in the world”.

Earlier, Chidambaram said Congress had amended the UAPA on six occasions and “nobody can point a finger at Congress and say we were soft on terror”. Pointing to the “ambiguous” provision of branding a person as terrorist just because the Centre believes him to be a terrorist, Chidambaram wondered whether it would be used against “eminent” persons accused in the Koregaon-Bhima violence including activists Gautam Navlakha, Shoma Sen and Varavara Rao etc.

Shah assured that designation of an individual as terrorist would be subject to a four-stage scrutiny, even as Chidambaram termed the provision “unconstitutional” and “certain to be struck down by the courts” as it went against personal liberties. The home minister said outfits often circumvented a UAPA ban by rebranding.