Tamil Nadu politics and women

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

History

1926-2021

Tara Krishnaswamy, March 13, 2021: The Times of India

From: Tara Krishnaswamy, March 13, 2021: The Times of India

From: Tara Krishnaswamy, March 13, 2021: The Times of India

From: Tara Krishnaswamy, March 13, 2021: The Times of India

From: Tara Krishnaswamy, March 13, 2021: The Times of India

TN women make better political leaders but there aren’t enough

Tamil Nadu gave India its first woman legislator as far back as 1926 — Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy. She was the first woman deputy president of the Madras Legislative Council. In her tenure, she helped draft, table, persuade and pass, what were then deemed heterodox bills.

The Devadasi Abolition Act was one she had to fight tooth and nail for, despite Mahatma Gandhi’s endorsement. Congress stalwart C Rajagopalachari wasn't in its favour and Congress leader S Satyamurthy opposed it, claiming that the system “protected” Hindu culture. It was only after she undertook ground campaigns, wrote extensively in the press, and Periyar publicly supported her, that the bill was passed.

She said, “women have grievances of some kind or other and suffer persecution, injustice and inequality of treatment ... women’s interests are different from that of men whose selfishness and claim to superiority inflict many hardships on women. Men being the source of women’s problems, women’s participation in public life alone could serve their interests.”

Women in Tamil Nadu have come a long way since then in the socio-economic realm. Five decades of Dravidian welfare politics has resulted in cut-above-the-rest female development indices. With 1,757 PhD holders per crore in the state, Tamil Nadu has triple the number of all-India doctorates per crore for women. At 39,794 postgraduates per crore for women, the state has double the number for postgraduates compared with the all-India average of 17,780.

The participation of TN women in the workforce is 10% points higher than the national average. The state tops the nation in the percentage of women police officers, and features among top three states in the higher judiciary.

Transitioning into the political landscape, the Special Summary Revision-2021 from the Election Commission shows there are 10 lakh more female (3,18,28,727) than male (3,08,38,473) voters in Tamil Nadu. If the trend of the past continues, women may vote in greater numbers than men in this election, indicating their vigorous political participation. However, political representation of women in the state assembly is woefully short. While women make up 50% of positions in rural and urban local governments due to reservation of seats, the state has seen single-digit percentage of female MLAs since 1962, except in two assemblies — 1991 (14%) and 2001 (11%.) It also bears the infamy of no woman being elected in the 1971 poll. This is despite data evidencing that victory rates of female candidates have been higher than their male counterparts, except on two occasions prior to 1991.

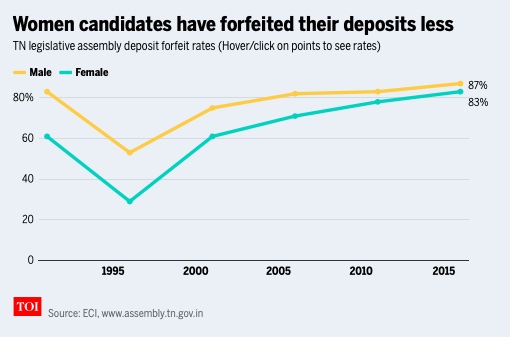

Female candidates have also been more viable, forfeiting their deposits less. Nevertheless, the Dravidian parties who have dually pioneered policy positions yielding tremendous socio-economic outcomes for women, have denied them the ballot.

The AIADMK fielded 12-16% of female candidates in 1991, 2001, 2006 and 2016. The party fielded just 6-7% of women in 1996 and 2011. The DMK fielded 11% of female candidates in 2016, 9% in the elections from 2001-2011, and 3%-4% in 1991 and 1996. It is evident that the AIADMK under former chief minister J Jayalalithaa was placing more women on the ballot than before, and was far ahead of the DMK. This reflects as a clear uptick in the Tamil Nadu legislative assembly male/female statistics.

But, in spite of nearly five decades of existence, the AIADMK today has no female leaders of national standing, not one Member of Parliament of either House, and no national spokeswoman. For the DMK, while Tuticorin MP Kanimozhi leads mammoth election rallies, a feat that very few female leaders are allowed to accomplish in electoral politics except when they are the candidate or chief of the party, the party projects hardly any female leaders.

Ultimately though, what counts is not the one or two larger-than-life female political leaders but the sheer count of women on the ballot. A critical mass of female lawmakers alone can lead to more robust laws and policies, crafted with the diversity of inputs from women’s lived experiences. If anything, the egregious GST of 16% on sanitary napkins compared to soft drinks, is an extant reminder of the bizarre impact of a low threshold of women in policy making.

In Tamil Nadu, political inclusiveness has historically defaulted to caste representation and gender blindness. Even though it pioneered women’s suffrage, inheritance laws, induction into the police forces and government jobs, it is telling that the ultimate frontier of political power has been denied to women. Without a minimum of one-third or 40% presence in the assembly, the diversity of women’s opinions is drowned out by the male majority. This results in policies that sometimes lack imagination. It is no surprise then, that women who aspire to make a mark in politics, disappointed time and again from rejection by their parties, believe that the Women’s Reservation Bill is the solution.

What both the legatees of social justice in the state need to realise is that gender justice is an intrinsic and inviolable part of political justice. The leapfrogging of Tamil Nadu’s development is not coming any more from just redeeming men across caste lines; indeed, it is impossible without women political leaders of all castes holding up half of Fort St George.

(The author is co-founder of Political Shakti)