Foodgrains and their management: India, Doctors in India

(→2018-19: Foodgrain output 1% lower) |

(→Court judgements) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {| Class="wikitable" | |

| − | + | ||

| − | {| | + | |

|- | |- | ||

|colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> | |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> | ||

| − | This is a collection of | + | This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/> |

| − | + | </div> | |

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | [[Category:India |D ]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Economy-Industry-Resources |D ]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Diaspora |D ]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Health |D ]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pakistan |D ]] | ||

| + | [[Category:China |D ]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Bangladesh |D ]] | ||

| − | = | + | =Availability of Doctors= |

| + | ==2010-11: India world’s top supplier of doctors== | ||

| + | '''Sources:''' | ||

| − | [http:// | + | 1. [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=India-top-supplier-of-docs-to-west-24092015001075 ''The Times of India''], Sep 24 2015 |

| − | + | 2. [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=India-No-1-in-supplying-docs-to-West-24092015009019 ''The Times of India''], Sep 24 2015, Lubna Kably | |

| − | '' | + | [[File: Number of expatrite Indian doctors and top 5 destinations for Indian migrants.jpg|Number of expatrite Indian doctors and top 5 destinations for Indian migrants; Graphic courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=India-No-1-in-supplying-docs-to-West-24092015009019 ''The Times of India''], Sep 24 2015|frame|500px]] |

| − | + | '''India top supplier of docs to west''' | |

| + | | ||

| − | + | India remains the top sup plier of expatriate doctors to 34 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, followed by China, reports Lubna Kably. | |

| + | According to a recent report, 86,680 Indian expatriate doctors worked in OECD countries, which include the US and EU bloc, during 2010-11 -up from 56,000 in 2000-01. The US employs 60% of expat Indian doctors; the UK is the second leading employer. | ||

| − | + | Philippines provided the most number of nurses at 2.21 lakh followed by India (70,471). | |

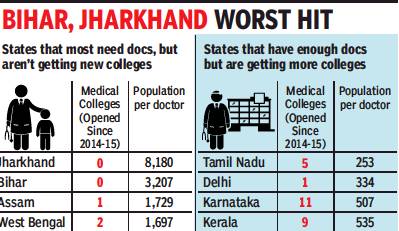

| − | + | ==2014-15: states with the most, least doctors/ medical colleges== | |

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F10%2F06&entity=Ar02307&sk=CA00B0DC&mode=text Rema Nagarajan, October 6, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| − | + | [[File: 2014-15- Indian states with the most and least doctors, medical colleges .jpg|2014-15- Indian states with the most and least doctors/ medical colleges <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F10%2F06&entity=Ar02307&sk=CA00B0DC&mode=text Rema Nagarajan, October 6, 2018: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | States like Jharkhand and Bihar with acute shortages of doctors have seen few new medical colleges being open in the last five years, while those with a glut of MBBS seats and doctors continue to allow new private colleges. This is despite doctors’ associations warning against overproduction of doctors. | |

| − | + | In Jharkhand, a state with the worst doctor-population ratio of just one doctor for over 8,000 people, no medical college has been started since 1969. Even in the last five years, which saw over 121 colleges being opened nationally, Jharkhand got none. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | In contrast, Kerala, already facing a glut of doctors with a doctor for 535 people, had nine colleges opening in the last five years, including 6 private ones accounting for 750 seats. | |

| − | + | But what can states do about where the private sector chooses to open medical colleges? For any medical college to be opened, the state has to issue an “essentiality certificate”, which certifies that a college is needed. The idea is to prevent unhealthy competition. This raises the question of why states producing more than enough doctors continue to hand out essentiality certificates. | |

| − | The | + | The results are showing in Karnataka where many colleges are in the news for getting fake patients during inspections since they don’t have enough to meet the norms. Many colleges that are allowed to admit students in the first year or for a few years are then derecognised when they no longer meet the MCI norms. |

| − | + | In Karnataka and Kerala, doctors’ associations have warned the governments against starting medical colleges as the glut of doctors is leaving many unemployed. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | New private colleges opening creates another problem. The essentiality certificate guarantees if the new college is disallowed admissions by the MCI in a subsequent year, the state government will take over responsibility for students already admitted. This has two effects. First, students who did not get into the much sought after government colleges get entry through the back door. Second, the teacher-student ratio takes a hit at these colleges. | |

| − | + | ==Density of doctors: 2017== | |

| − | + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F09%2F02&entity=Ar01218&sk=00378C59&mode=text Rema Nagarajan, 6 states have more docs than WHO’s 1 doc/1k people norm, September 2, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | |

| − | The | + | [[File: The Density of doctors in Indian states, presumably as in 2017.jpg|The Density of doctors in Indian states, presumably as in 2017 <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F09%2F02&entity=Ar01218&sk=00378C59&mode=text Rema Nagarajan, 6 states have more docs than WHO’s 1 doc/1k people norm, September 2, 2018: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] |

| − | + | ''Yet Rural Areas Remain Underserved'' | |

| − | + | Even as governments cite shortage of doctors to allow more private medical colleges, six states — Delhi, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Punjab and Goa — have more doctors than the WHO norm of one for 1,000 people. Yet, some can’t find enough doctors for rural public health system. Also, most doctors from these states are unwilling to move to states like Bihar or UP that suffer from an acute shortage. This again raises the question of whether merely producing more doctors can address the crunch in public health and in rural areas. | |

| − | + | The density of doctors per 1,000 people in Tamil Nadu is as high as 4, almost at the same level as countries like Norway and Sweden, where it is 4.3 and 4.2 respectively. In Delhi, the density is 3, higher than the UK, US, Canada and Japan, where it ranges from 2.3 to 2.8. In Kerala and Karnataka, the density is about 1.5 and it is about 1.3 in Punjab and Goa. | |

| − | + | TOI calculated these densities after deducting 20% from the number of registered doctors, as is done by the Medical Council of India to estimate the number of doctors available, since many state councils have not updated their registries. In states that have updated them through periodic reregistration, as in Delhi, the 20% reduction was not applied. | |

| − | + | Since India’s doctors are largely concentrated in urban areas, it is possible that even some states with doctor population ratios better than 1:1,000 may have shortages in rural areas. However, Tamil Nadu and Kerala boast that they have no vacancies in their rural public health systems. | |

| − | + | According to Dr Prabhakar DN, former president of the Karnataka branch of the Indian Medical Association, 40% of doctors in Karnataka are in Bangalore. “In rural areas, there is still a shortage. Bangalore is saturated, even for specialists. So they don’t get jobs. Doctor salaries are coming down... We need to focus on producing doctors for the periphery. Just producing more doctors won’t work,” he added. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | “Unlike engineers, who typically need to find jobs, doctors can be self-employed. If there are too many in a geographical area, they resort to unethical practices on the few patients they get to make ends meet. That’s why there is a need to calibrate the number being produced. We have told the state government to stop allowing the opening of more private colleges. They should shut down many of those that are in a bad shape, with no patients and no money to pay their faculty. The IMA is having to intervene each time to help them as they are not paid for six to eight months,” said Dr N Sulphi, secretary of the Kerala IMA. | |

| − | == | + | ==MCI list, 2018: outdated but has historical nuggets== |

| − | [ | + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F08%2F07&entity=Ar01109&sk=924FECF6&mode=text Rema Nagarajan, How many doctors does India have? Well, no one really knows, August 7, 2018: ''The Times of India''] |

| − | |||

| − | + | ''MCI Record Not Up To Date, Lists Even Those Who Registered In 1915'' | |

| − | + | How many doctors does India have? Going by data given to Parliament by the Medical Council of India (MCI), there are more than 10.8 lakh doctors registered. In reality, no one really knows as is evident from the MCI’s own answer that 80% availability has to be assumed from this total number. | |

| − | + | Why 80% and not 90% or 75%? A look at the Indian Medical Registry (IMR) makes it clear why no one knows exactly how many doctors are alive and practicing. Here are a few examples of doctors found in the registry. | |

| − | + | Dinabandhu Basak, who qualified as an LMF (licenciate of medical faculty) from the University of London in 1895, and registered with the West Bengal Medical Council in 1915; Surendra Chandra Majumder, LMP (licenciate in medical practice) from Dibrugarh University in 1907, who registered with the Assam Medical Council in 1920; Shashi Bhushan Dutta, LMS (licenciate in medicine and surgery from Calcutta University in 1911, registered in 1918 with the Bihar Medical Council; Captain Christian Salvadore, MBBS from Kerala University in 1914, registered with the Travancore council in 1945; Y Sheshachalam, LMP from Madras University in 1916, registered in 1955 with the Andhra Pradesh council. | |

| − | India had | + | Over 75,000 of the doctors in the IMR registered before independence or a little after it, some as early as the 19th century as the examples given show. It seems safe to assume that a majority of them are dead or not practicing any more. Yet their names remain on the register and are counted year after year. Repeated directions since at least 2009 to state councils to re-register all doctors to weed out those who might have died, migrated, or stopped practicing have yielded little or no result. |

| + | |||

| + | One council with a live register is the Delhi Medical Council. But in this case, the data given to Parliament shows just 16,833 doctors registered in Delhi while the DMC itself says there are over 64,000. DMC president Dr Arun Gupta explained: “We have 48,657 re-registrations and 15,720 first-time registrations. Thus a total of 64,377 doctors registered with our council. So we have a fairly good idea of the actual number of doctors in Delhi.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Unlike Delhi, MCI says many states like Haryana, Bihar, Orissa and Karnataka have not sent it the registration data for several years. “The State Medical Councils are established under an Act of the respective state legislatures. They are independent statutory authorities and MCI does not enjoy any supervisory role or control over them,” explained MCI President Dr Jayshree Mehta. According to the Indian Medical Council Act of 1956, under which the MCI is constituted, it is the statutory duty of the council to maintain the IMR. The Act also mandates state councils to supply MCI with a copy of their registers after April 1 of each year with all additions and amendments. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As a result, year after year, Parliament is given the same meaningless data without any effort by the health ministry, MCI or state councils to clean it up. Why does this matter? The health ministry calculates the shortage of doctors based on this data. In the age of Digital India and Aadhaar, it seems inexplicable that the government is unable to maintain a database of barely 10 lakh doctors. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Last year, the MCI had tried to initiate a system of Unique Permanent Registration Number (UPRN) for every doctor to be able to track them in cases of medical negligence, to get a clearer picture of how many doctors are practicing in India and to tackle the menace of fake doctors or ones with unrecognised degrees. The fact remains that over 60 years after it came into existence, the MCI has been unable to do the basic function of getting the IMR right. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Actual numbers: MCI vs. state councils=== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F08%2F16&entity=Ar01219&sk=F39A7EEC&mode=text Rema Nagarajan, State councils blame MCI for mess in data on doctors, August 16, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: The number of doctors in five Indian states. presumably as in 2017- MCI vs. state councils.jpg| The number of doctors in five Indian states. presumably as in 2017: MCI vs. state councils <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F08%2F16&entity=Ar01219&sk=F39A7EEC&mode=text Rema Nagarajan, State councils blame MCI for mess in data on doctors, August 16, 2018: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Several State Medical Councils have expressed shock at the Medical Council of India (MCI) submitting outdated and wrong data to Parliament year after year. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to the officebearers of these councils, they have been sending updated lists to the MCI but do not see it reflected in the Indian Medical Register (IMR). Maintaining the IMR is one of the fundamental and statutory duties of the MCI. | ||

| + | |||

| + | While the MCI told TOI the state councils were to blame for not regularly sending information on registered doctors to it, most state councils refuted this allegation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the case of Karnataka, for instance, the MCI data submitted to Parliament recently showed 1.04 lakh doctors registered. The data MCI gave TOI also said the state council had not submitted any data in 2015 or 2016. However, the state council insisted it has been submitting data every quarter. The Karnataka Medical Council started the process of re-registration of doctors every five years in 2013 and after renewal had about 123,436 doctors in the registry as of March 2018, nearly 20,000 more than the MCI data shows. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “It is disrespect to Parliament to not make any effort whatsoever to give the latest data and not even explain to Parliament that the data being submitted has not been updated,” said KMC president, Dr H Veerbhadrappa. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Maharashtra Medical Council (MMC) has not only done the process of reregistration of doctors every five years, the entire list of 86,567 doctors registered with it is available on the council’s website. “We have the most modern system. The revalidated data has been shared with the MCI, but it is still not reflected in the IMR,” said MMC president Dr Shivkumar S Utture. The MCI data shows 1.59 lakh doctors in Maharashtra, nearly twice as many as the state council’s number. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The MCI responded to the state councils’ claims by insisting the Karnataka figures it had put out were correct and that in Maharashtra’s case the state council had submitted no data for 2016 and data in a “wrong format” for 2017 only this month. It said, “as per the office records, we assure you that no wrong information has been submitted to the parliament.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since Karnataka and Maharashtra have a large number of medical colleges, they have many out-of-state students registering with these councils immediately after completing MBBS. But then they take no objection certificates (NOC) and go to their respective states. The NOCs issued are tracked and the names are removed from the register. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Even office-bearers of the Travancore-Cochin Medical Council that registers all doctors in Kerala, who have sent their details to the MCI so many times find their names have not yet been included in the IMR. Then you can imagine just how well they are maintaining the database,” pointed out Dr VG Pradeep Kumar, vice-president of the council. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==STATE-WISE== | ||

| + | ===Delhi, 2019: a shortage in govt. hospitals=== | ||

| + | [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/lack-of-docs-puts-hospitals-on-life-support/articleshow/68729933.cms Abhinav Garg, Durgesh Nandan Jha, Lack of doctors puts Delhi's hospitals on life support, April 5, 2019: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: Delhi, 2019- a shortage of doctors in govt. hospitals.jpg|Delhi, 2019: a shortage of doctors in govt. hospitals <br/> From: [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/lack-of-docs-puts-hospitals-on-life-support/articleshow/68729933.cms Abhinav Garg, Durgesh Nandan Jha, Lack of doctors puts Delhi's hospitals on life support, April 5, 2019: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | A status report filed by the state government in Delhi high court says there is an acute crisis of manpower in Delhi’s state-run hospitals. For instance, in GB Pant Hospital, the largest of the government’s super-specialty institutions, 159 posts for doctors are vacant, while the paramedical/nursing and non-medical strengths are short by199 and 233, respectively. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The situation in LNJP, Deen Dayal Upadhyay, Ambedkar and Guru Tegh Bahadur hospitals, among the biggest tertiary care centres in Delhi, are not reassuring either. The status report says that in LNJP, there are 41 vacancies among doctors, 15 among paramedical staff and 229 among the non-medical staff. Hospital sources said the figure for doctors related only to non-teaching specialists. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The report was filed in response to the persistent queries of the bench of chief justice Rajendra Menon and justice V K Rao, which had sought to know last year about the specific steps taken by the government to improve health facilities. The bench is hearing a PIL filed by Madhu Bala, a schoolteacher in Karawal Nagar who lost her baby after admission to GTB Hospital for delivery. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Bala’s lawyer Prashant Manchanda alleged in the petition that the hospital’s woeful infrastructure and lack of medical facilities were behind the loss of the baby and the near death of his client. He claimed the hospital did not perform a crucial surgery pleading “non-availability” of an OT. The petition urged the high court to step in “to immediately resurrect the dangerously dilapidated health system in public hospitals and utilise huge funds to infuse instant course correction and overhauling to prevent further health hazards”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To begin with, the concerned court demanded details of the “infrastructural facilities available, the requirement of manpower for running of the hospitals and various other issues like functioning of equipment, installation of necessary equipment for treating the patients, etc” at the five hospitals. It directed the government to furnish information on life-saving equipment, drugs, beds, operation theatres and staff, among others. However, at the previous hearing, the court asked for more details as it was not satisfied by the data furnished by Delhi government’s Director General of Health Services on behalf of the hospitals. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The real crisis is the depleted nursing staff and technicians. There have been occasions when surgeries had to be postponed due to the unavailability of nursing orderlies and safai karamcharis,” admitted a doctor at LNJP, who did not want to be quoted. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to information furnished by the hospital, there are 436 sanctioned posts for safai karamcharis, of which 167 are currently vacant. There are no x-ray attendants, and the number of operation theatre attendants is also half the sanctioned strength. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In DDU Hospital, the largest government hospital in west Delhi and visited by over 4,000 patients daily, the data compiled by the government and shared with the high court shows a quarter of the posts of regular doctors in the 640-bedded hospital is vacant. The vacancy among the resident doctors and nursing staff is 15% and 10%, respectively. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Kerala has 3.3 times as many doctors as WHO norm/ 2019=== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2019%2F03%2F21&entity=Ar01015&sk=DA3C6A7D&mode=text Preetu Nair, In Kerala’s ‘sick’ hospitals, doctors are first casualty, March 21, 2019: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: The availability of Doctors in Kerala, presumably as in 2019..jpg|The availability of Doctors in Kerala, presumably as in 2019. <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2019%2F03%2F21&entity=Ar01015&sk=DA3C6A7D&mode=text Preetu Nair, In Kerala’s ‘sick’ hospitals, doctors are first casualty, March 21, 2019: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''State Has A Doc-Population Ratio Of 1:300 While WHO Prescribes 1:1000'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wedged between corporate hospitals with deep pockets and a vastly improved public healthcare system, mid-level private hospitals across Kerala are either not paying their doctors on time or forcing them to accept drastic pay cuts. In some hospitals, they are even retrenching doctors. The most affected are 50 to 100-bed hospitals. Of the 23 private medical colleges, about five are at present paying their doctors on time. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “It’s true that many hospitals are unable to pay doctors on time. Even senior specialist doctors are affected”, Indian Medical Association (IMA) state secretary Dr N Sulphi said. According to IMA Kerala estimates, of the 800-odd 50 plus-bedded healthcare institutions, around 100 hospitals are facing financial crisis and unable to pay doctors’ salaries. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ironically, Kerala’s remarkably high doctor-topopulation ratio — WHO prescribes a doctor-population ratio of 1:1000, while in Kerala the ratio is 1:300 — could be at the root of the problem. There are around 70,000 doctors registered with Travancore Cochin Medical Council , of around 55,000 are practicing in Kerala. Of the 55,000, almost 50% are specialist doctors and get an average Rs 1.25 lakh to Rs 1.5 lakh salary per month. The around 1,200 super-specialist doctors in the state get anything between Rs 2.5 lakh and Rs 3 lakh per month. In a good hospital that has been in existence for more than 4 to 5 years, the doctor’s salary constitutes 20% of the total cost. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Some are even forced to take a salary cut while taking a new job,” Dr Sulphi said. With almost 60% to 70% of doctors working as consultants, they don’t even have proper leave facility. There are no social security measures in place. With more doctors losing jobs, IMA has intervened and asked hospitals to at least honour contracts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “We spend crores to set up speciality units but often doctors are unable to live up to the expectation and we don’t even get enough money to repay loans. Then we either have to reduce doctor’s salary or close down the unit,” said Kerala Private Hospitals Association (KPHA president Dr PK Mohamed Rasheed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kerala state planning board member Dr B Eqbal said, “With facilities in the government hospitals improving, people are opting for government hospitals. From just 25% patients availing services at government hospitals in the past, now it is jumped to 40%”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Court judgements= | ||

| + | ==2018: HC fines doctors ₹5,000 for poor handwriting== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F10%2F04&entity=Ar01213&sk=909B56C1&mode=text Ravi Singh Sisodiya, October 4, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '' ‘ILLEGIBLE WRITING OBSTRUCTION TO COURT WORK’ '' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Poor handwriting of doctors are not really surprising, but a court in Uttar Pradesh has put that on record now. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A Lucknow bench of Allahabad high court has imposed Rs 5,000 penalty each on three doctors in separate cases for their illegible handwriting. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the three criminal cases that came up for hearing last week, the injury report of the victims issued by hospitals from Sitapur, Unnao and Gonda district hospitals were “not readable” because the handwriting of the doctors who had issued them were “very poor”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The bench considered it an obstruction in the court work and summoned the three doctors — Dr TP Jaiswal of Unnao, Dr PK Goel of Sitapur and Dr Ashish Saxena of Gonda. A bench of Justice Ajai Lamba and Justice Sanjay Harkauli admonished them and asked them to deposit Rs 5,000 penalty in the court’s library. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The doctors pleaded they erred in writing legible prescriptions as they were overburdened. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The court further directed principal secretary (home), principal secretary (medical & health) and director general (medical & health) to ensure that in future, medico reports are prepared in “easy language and legible handwriting”. The court also suggested that such reports should be computer-typed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The medico-legal report, if given clearly, can either endorse the incident as given by the eyewitnesses or can disprove the incident to a great extent. This is possible only if a detailed and clear medico-legal report is furnished by the doctors, with complete responsibility,” the bench observed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It added, “The medical reports, however, are written in such shabby handwriting that they are not readable and decipherable by advocates or judges. It is to be considered that the medico-legal reports and post-mortem reports are prepared to assist the persons involved in dispensation of criminal justice. If such a report is readable by medical practitioners only, it shall not serve the purpose for which it is made.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The court reminded the doctors of a circular issued by UP director general (medical & health) in November 2012 which stipulated doctors to prepare medico-legal reports in readable for m. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Emoluments= | ||

| + | ==As in 2020?== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2020%2F06%2F08&entity=Ar00106&sk=182AE192&mode=text Hemali Chhapia, Delhi, UP pay resident docs most, interns in Maha among worst paid, June 8, 2020: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: States that pay doctors the best and the worst, presumably as in 2019 or ’20.jpg| States that pay doctors the best and the worst, presumably as in 2019 or ’20. <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2020%2F06%2F08&entity=Ar00106&sk=182AE192&mode=text Hemali Chhapia, Delhi, UP pay resident docs most, interns in Maha among worst paid, June 8, 2020: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | Delhi, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar pay resident doctors (MBBS degree holders pursuing postgraduation) the most. Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Gujarat and Haryana are also among the better paymasters for doctors at different levels in government-run hospitals. Interns (those in the final year of their MBBS course) in Maharashtra are among the worst paid even after a recent hike; only three other states, Rajasthan, MP and UP, pay lower. And specialists – senior residents pursuing a superspecialty course – are better off in the rural parts of Chhattisgarh, Haryana and UP where they earn Rs 1 lakh to 1.5 lakh a month, compared to Maharashtra where they get an average Rs 59,000. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Interns at Centre-run hosps get highest pay ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | At a time when resident doctors across the country are on the frontlines attending to Covid-19 patients, there is wide variation in their stipend depending on which part of India they serve. Chhattisgarh pays the maximum. UP, Bihar, Jharkhand, Haryana, all pay Rs 80,000-Rs 1 lakh a month while Maharashtra and the southern states lie in the mid-range, paying a monthly stipend of Rs 40,000-Rs 60,000. The Medical Council of India plans to make stipend post-MBBS uniform across the country, but the plan is yet to be cleared by all states. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Interns posted in central government-run hospitals are paid the highest, Rs 23,500 a month. Across India in staterun hospitals, their stipend varies from as low as Rs 7,000 in Rajasthan to the highest in Karnataka now at Rs 30,000. Medical interns are students who have completed four-anda-half years at a med school and do their compulsory rotational residential internship at a hospital attached to the medical college before getting the MBBS degree. | ||

| + | |||

| + | While interns in Maharashtra get a stipend of Rs 6,000, it was recently hiked to Rs 11,000 by the state. But BMC hospitals in Mumbai are yet to effect the change. Residents and senior residents in the state get Rs 54,000 and Rs 59,000, respectively (average of three years). The BMC recently announced a temporary stipend of Rs 50,000 for MBBS interns for their work in the Covid-19 wards. But a permanent increase of Rs 10,000 is expected for residents, said the head of the Directorate of Medical Education and Research in Maharashtra Dr T P Lahane. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At the postgraduate level, the stipend varies for every state as also for each year of the resident. In some states, there are multiple scales; to attract talent, the stipend offered to residents in rural areas is higher compared to what is paid in urban centres. For instance, in Chhattisgarh, residents in rural areas are paid Rs 20,000-30,000 more and seniors are paid Rs 1.5 lakh as compared to their counterparts in city hospitals who take home Rs 1.3 lakh a month. One of the reasons Bihar, UP, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand pay government doctors much higher, experts say, is because of the dependence on the public healthcare network in these states as compared to Maharashtra, TN or Karnataka, which have more hospitals driven by charitable trusts and private practitioners. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Founder member of Alliance of Doctors for Ethical Healthcare Dr Babu KV has for long been writing to the MCI for a uniform stipend for interns, residents and seniors. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Bangladesh|D | ||

| + | DOCTORS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:China|D | ||

| + | DOCTORS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Diaspora|D | ||

| + | DOCTORS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Economy-Industry-Resources|D | ||

| + | DOCTORS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Health|D | ||

| + | DOCTORS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|D | ||

| + | DOCTORS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pakistan|D | ||

| + | DOCTORS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Health issues= | ||

| + | == Kerala doctors die earlier than general public== | ||

| + | [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kochi/docs-die-early-than-gen-public-study/articleshow/61716443.cms Nov 20, 2017: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''HIGHLIGHTS''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Doctors in Kerala are dying younger when compared to the general public according to a study conducted by Indian Medical Association. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Majority of doctors in Kerala die due to cardio-vascular diseases and cancer. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Life expectancy of an Indian is 67.9 years and that of a Malayali is 74.9 years, the mean ‘age of death’ for a Malayali doctor is 61.75 years | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Doctors heal and help people live longer, but it seems many of them are dying younger when compared to the general public in Kerala. A study conducted by research cell of the Indian Medical Association (IMA) in Kerala found that a majority of them die due to cardio-vascular diseases and cancer. | ||

| − | + | While the life expectancy of an Indian is 67.9 years and that of a Malayali is 74.9 years, the mean 'age of death' for a Malayali doctor is 61.75 years, said the study. "We were surprised by the figures as we expected doctors to live longer as they know what is good for them," said IMA research cell convener Dr Vinayan KP. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | For the 10-year study - titled Physician's Mortality Data from 2007 to 2017 - the mortality pattern among doctors enrolled with state IMA's social security scheme was analysed. Of the 10,000 doctors who were part of the contributory supportive scheme that provides a fixed amount to deceased doctor's family, 282 died during the study period. | |

| − | + | Of this, 87% were men and 13% women. Almost 27% died due to heart diseases, 25% due to cancer, 2% died due to infection and another 1% committed suicide. | |

| − | '' | + | The study didn't look at the reasons for early death, but doctors reasoned that stress was a major contributor. "Doctors are generally working under a lot of stress irrespective of government or private jobs. Increased working hours, the patients they attend to and high expectations contribute to this increased stress. Their working hours need to be fixed, besides government social security scheme. Also doctors should be prepared for periodic health check-ups," said IMA's former president Dr VG Pradeep Kumar. |

| − | + | "Being a doctor in India is injurious to one's health now. Due to stress, doctors are more prone to heart disease, diabetes and even paralysis," said IMA national president Dr KK Aggarwal. While IMA's national study showed that doctors were dying on an average 10 years earlier than the general population; in Kerala - a state with high life expectancy -they die nearly 13 years earlier. | |

| − | + | IMA, Kerala is in the process of doing a prospective study on the health profile of all its members - their lifestyle, food habits. It also will see whether doctors themselves go for a regular medical check-up. "The present study is a retrospective study and has its limitations. We don't know the lifestyle and habits of those who died. Also some elderly doctors may not be part of the scheme as it is a voluntary one introduced much after IMA was formed here," said Dr Vinayan. | |

| − | + | Health expert Dr B Ekbal (one of the few doctors in the state who is not an IMA member) said that a detailed study covering all doctors was essential before reaching a final conclusion. "This may be an indication about doctor's health, but a detailed study is needed," he said. | |

| − | + | =Quality of care of patients= | |

| + | ==Doctor-Patient ratio: 2007-14== | ||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Number-of-doctors-on-the-rise-but-ratio-24092015009025 ''The Times of India''], September 24, 2015 | ||

| − | + | ''Number of migrant healthcare professionals in OECD nations sees 60% rise'' | |

| − | |||

| − | + | India continues to retain its position as the world's top supplier of expatriate doctors to 34 member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), followed by China. Most new immigrants to OECD countries--taking migration statistics in totality--though, originated from China, with India occupying the fourth slot. | |

| + | According to the International Migration Outlook (2015), the number of Indian expatriate doctors to the OECD jumped 55% to 86,680 in 2010-11 from 56,000 in 2000-01. The US employs 60% of the expatriate Indian doctors, with the UK being the second leading employer. China, with 26,583 expatriate doctors in 2010-11, was a distant second overall. The OECD includes, among others, the US, EU countries, Switzerland and Australia. | ||

| − | + | Philippines provided the most nurses--around 2.21 lakh--compared to India at 70,471. The number of expat nurses from India, though, has grown over the past ten years, which has seen India move to the second spot in 2010-11 from its sixth position earlier. Expat nurses from India are found primarily in the US (42%), the UK (28%) and Australia (9%). | |

| − | + | In total, the number of migrant doctors and nurses working in OECD countries has risen 60% over the past ten years. Expat doctors and nurses constituted 23% and 14% of healthcare profes sionals in OECD countries. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | “The trend mirrors the general increase in immigration to OECD countries, particularly of skilled workers,“ states the report, pointing out that a number of OECD countries have revised their migration laws in the past few years, hinging towards restriction. | |

| − | + | Several countries have cast a greater onus on the potential employer to ensure expats only with right skills are granted employment--advertising for local employees and payment of a threshold salary for expat employees (to ensure that lower salaries don't become the sole ground for hiring expats) are among the measures adopted by various countries, especially those in EU. | |

| − | The | + | The total foreign-born population in OECD countries stood at 11.7 crore people in 2013--3.5 crore more than in 2000. 2014 data suggests permanent migration flow to OECD countries reached 4.3 lakh--a 6% increase compared to 2013. |

| − | + | Most new immigrants to OECD countries originated from China, accounting for around 10% of migrants in 2013, followed by Romania and Poland. This is largely attributed to intra-EU mobility.Comparatively, India appeared in fourth position, with 4.4% of immigrants. | |

| − | + | OECD countries have also seen an increase in the number of foreign students. In 2012, there were nearly 34 lakh foreign students in OECD countries--a slight rise of 3% compared to 2011. Most students in the area of higher education originated from Asia, with India accounting for 6%. International students account for an average of 8% of the OECD tertiarylevel student population. | |

| − | + | ==On average see patients for 2 minutes/ 2017== | |

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Docs-in-India-see-patients-for-barely-2-09112017035009 Malathy Iyer, Docs in India see patients for barely 2 min: Study, November 9, 2017: The Times of India] | ||

| − | + | [[File: The average time a doctor spends in consulation with patient, Bangladesh, China, India and the world, 2017.jpg|The average time a doctor spends in consulation with patient, Bangladesh, China, India and the world, 2017 <br/> From: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Docs-in-India-see-patients-for-barely-2-09112017035009 Malathy Iyer, Docs in India see patients for barely 2 min: Study, November 9, 2017: The Times of India]|frame|500px]] | |

| − | + | The average time that India's neighbourhood doctors, called primary care consultants, spend with patients is a negligible two minutes. Neighbouring Bangladesh and Pakistan seem worse off, with the length of medical consultation averaging 48 seconds and 1.3 minutes, respectively, according to the largest international study on consulting time, published in medical journal BMJ Open. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | ' | + | Contrast this with firstworld countries such as Sweden, the US or Norway where a consultation crosses 20 minutes on an average. “It is concerning that 18 countries covering around 50% of the world's population have a latest-reported mean consultation length of five minutes or less. Such a short consultation length is likely to adversely affect patient care and the workload and stress of the consulting physician,“ said the BMJ Open study conducted by researchers from various UK hospitals. Patients are the losers here, spending more at pharmacies, overusing antibiotics and sharing a poor relationship with their doctors, said the study . |

| − | + | The shorter consulting time could mean larger problems in the healthcare system. In the Indian context, local experts said it is a reflection of overcrowded healthcare hubs and a shortage of primary care physicians. | |

| − | + | Primary care doctors are different from consultants trained in a particular branch of medicine. | |

| − | The | + | The finding of an average two-minute consult across India didn't surprise many .Health commentator Ravi Duggal said, “It is well known that patients get less time with doctors due to overcrowding in hospitals.“ Doctors in public hospitals end up consulting two to three patients at one time due to the crowds at OPDs. “It is, hence, not uncommon for doctors to mix up symptoms between two patients,“ he said. |

| − | + | Private clinics and hospitals are not less crowded. “Private doctors, especially general physicians, have such crowded OPDs that they only listen to symptoms and rarely conduct a physical examination,“ said Duggal, adding that a patient's quality of care gets compromised in the process. | |

| − | + | Former Maharashtra Medical Council member Suhas Pingle blamed overcrowded clinics and the overburdened healthcare system. | |

| − | + | There is also India's peculiar “prescription“ of a good doctor. “In India, we believe the best doctor is one who doesn't charge and is available 24x7.This is not practical,“ said Dr Pingle. Many doctors take lower charges so that they can get more patients. “Consultation length will obviously be shorter because there are only so many hours that a doctor can work,“ said the general physician. | |

| − | The | + | The main difference between western and Indian consultation is the nature of the disease. The BMJ Open study looked at the overall picture of poor primary healthcare in countries. |

| − | == | + | =Rural postings= |

| − | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2019%2F03% | + | ==Maharashtra’s incentives, punishments/ 2015-19== |

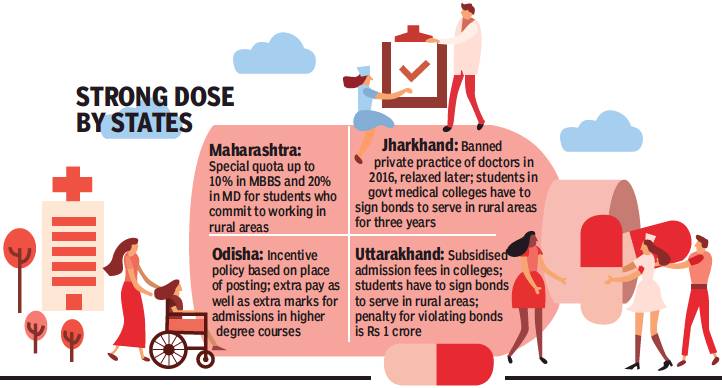

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2019%2F03%2F16&entity=Ar01704&sk=C5BF5189&mode=text (With reports from Chaitanya Deshpande, Ashok Pradhan, Dhritiman Ray, Sheezan Nezami, and Shivani Azad), What gets docs to villages: Double pay, cheaper edu, salary cut, fines..., March 16, 2019: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | [[File: Rural postings for doctors- rules in Maharashtra, Jharkhand, Odisha and Uttarakhand, as in March 2019.jpg|Rural postings for doctors- rules in Maharashtra, Jharkhand, Odisha and Uttarakhand, as in March 2019 <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2019%2F03%2F16&entity=Ar01704&sk=C5BF5189&mode=text (With reports from Chaitanya Deshpande, Ashok Pradhan, Dhritiman Ray, Sheezan Nezami, and Shivani Azad), What gets docs to villages: Double pay, cheaper edu, salary cut, fines..., March 16, 2019: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | Maharashtra drafted a bill to create a special reservation quota up to 10% in undergraduate (MBBS) and 20% in post-graduate (MD) medical seats for those who give a commitment to work in tribal and rural areas. Candidates must serve for a period of seven years immediately after completion of MBBS and for five years after MD. | |

| − | + | Across rural India, particularly in tribal and remote areas, the crisis in the healthcare sector has been compounded by a severe lack of doctors. States have been promoting various incentives to make new doctors opt for rural postings, but with mixed success. | |

| − | + | “The healthcare situation in rural Maharashtra is dire. There is a huge network of 1,816 primary health centres, 400 rural hospitals, 76 sub-district hospitals and 26 civil hospitals. But this is rendered useless because of lack of manpower,” said healthcare activist Dr Amol Annadate. | |

| − | + | The situation is perhaps worse in Odisha, which has a large population in remote areas. Now, though, it has introduced a system which is beginning to make a difference. Starting April 2015, a place of posting-based incentive policy for doctors was started by dividing the 1,750 government hospitals into five categories: from V0, the least vulnerable hospitals, to V4 the most difficult ones. These categories are based on backwardness of the area, Left-wing extremism, road/train communication, social infrastructure and distance from the capital. | |

| − | + | Those posted in V4 category get 100% extra pay, while general medical officers in V4 hospitals get Rs 40,000 per month more and specialists Rs 80,000 additionally. There are 100 V4 and 137 V3 hospitals. Doctors working in V1 to V4 institutions get additional marks in postg raduate entrance examinations. “Young doctors are interested in joining remote and inaccessible areas to get additional marks for selection in PG courses,” health secretary Pramod Meherda said. | |

| − | + | A doctor who has served in V4 institutions gets 10% extra marks in NEET for every year he has served, up to three years. Those who have served in V1 institutions will get 2.5% extra; V2 5% and V3 7.5%. | |

| − | + | These measures have begun having some impact: as of December 2018, the KBK (Kalahandi-Balangir-Koraput) region had 1,072 doctors compared to 786 in March 2014. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Next door in Jharkhand, 65% of women are anemic. Vector-borne diseases like malaria, kala azar and Japanese encephalitis are endemic. Malnutrition is also above the national average. And the number of vacancies for doctors is more than half the total number of posts. | |

| − | + | The government in 2017 began constructing three new medical colleges in Palamu, Dumka and Hazaribagh to increase the number of MBBS seats, which stands at 350 (combining medical colleges in Ranchi, Jamshedpur and Dhanbad). Three more colleges were announced in Bokaro, Koderma and Chaibasa. With existing medical colleges reeling under shortage of faculty, the retirement age of serving faculty members was raised to 65 years. | |

| − | + | “We have a sanctioned strength of nearly 11,000 doctors in state health service, of which approximately 6,000 are vacant,” a senior official in health department said. “Doctors do not want to work in district hospitals and CHCs because the pay is low and these places are remote and have law and order problems,” the official added. Of Jharkhand’s 24 districts, 19 are affected by Maoism. That in turn has hit healthcare. | |

| − | + | Private players were roped in to set up clinical and radiological test centres in district hospitals. In February this year, a Hyderabad based health-chain was given the nod to set up telemedicine centers in 110 CHCs. A pilot project was started in Ranchi in January whereby privately-employed doctors would be paid to visit rural health centres to set up camps and perform surgeries. | |

| − | + | State health secretary Nitin Madan Kulkarni said, “We have rolled out a recruitment process for specialist doctors. In-principle approval has been given for additional allowances and incentives to medical officers in 2019-20.” | |

| − | + | The Uttarakhand government has tried various carrot and stick methods to get physicians to work in remote areas. | |

| − | + | Since 2008, MBBS courses are being offered at subsidised rates in state-run medical colleges to students who sign a bond that mandates them to serve in the hills after graduation. The subsidised fee ranges between Rs 15,000 and Rs 40,000 per year (a similar MBBS course in a private college would cost Rs 5 to Rs 7 lakh per year). However, most MBBS graduates do not honour terms of the bond even though the state government raised the penalty amount for defaulters to Rs 1 crore in 2017. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The medical education department recently issued legal notices for recovery of money to 383 doctors for not keeping their commitment to serve at least five years in the hills in exchange for subsidised education. In 2016, the health department published notices in leading dailies about those doctors who were shifted to the hills months ago but did not join duty. This was done to “name and shame” them. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Doctors, however, said lack of adequate infrastructure was the reason for their reluctance to serve in remote areas. “Even if we go to hill postings, our hands are tied because equipment available to us is not adequate. Also, emergency and trauma facilities are missing,” said Dr NS Napchyal, former general secretary of Uttarakhand Provincial Medical Health Services. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | =Violence= | ||

| + | ==40% of govt docs face violence== | ||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Study-40-of-govt-docs-face-violence-21032017001029 Study: 40% of govt docs face violence, Mar 21, 2017: The Times of India] | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | Nearly one in every two doctors (41%) suffers violence at public hospitals, a survey conducted at Delhi's Maulana Azad Medical College revealed. The study covered 169 junior residents and senior residents, most of them working at Lok Nayak and G B Pant hospitals, reports Durgesh Nandan Jha. Verbal abuse was the most rampant form of violence, reported by 75% of respondents who said they had suffered some form of violence. More than half of such respondents (51%) reported getting threats and 12% said they had been physically assaulted. All doctors who faced physical violence said they felt angry, frustrated and fearful. | |

| + | =See also= | ||

| + | [[Doctors in India]] | ||

| − | + | [[Medical education and research: India]] | |

| − | [[ | + | |

| − | [[ | + | [[Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research, Kolkata]] |

| − | [[ | + | [[Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education & Research (JIPMER), Puducherry]] |

Revision as of 12:07, 6 October 2020

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents

|

Availability of Doctors

2010-11: India world’s top supplier of doctors

Sources:

1. The Times of India, Sep 24 2015

2. The Times of India, Sep 24 2015, Lubna Kably

India top supplier of docs to west

India remains the top sup plier of expatriate doctors to 34 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, followed by China, reports Lubna Kably. According to a recent report, 86,680 Indian expatriate doctors worked in OECD countries, which include the US and EU bloc, during 2010-11 -up from 56,000 in 2000-01. The US employs 60% of expat Indian doctors; the UK is the second leading employer.

Philippines provided the most number of nurses at 2.21 lakh followed by India (70,471).

2014-15: states with the most, least doctors/ medical colleges

Rema Nagarajan, October 6, 2018: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, October 6, 2018: The Times of India

States like Jharkhand and Bihar with acute shortages of doctors have seen few new medical colleges being open in the last five years, while those with a glut of MBBS seats and doctors continue to allow new private colleges. This is despite doctors’ associations warning against overproduction of doctors.

In Jharkhand, a state with the worst doctor-population ratio of just one doctor for over 8,000 people, no medical college has been started since 1969. Even in the last five years, which saw over 121 colleges being opened nationally, Jharkhand got none.

In contrast, Kerala, already facing a glut of doctors with a doctor for 535 people, had nine colleges opening in the last five years, including 6 private ones accounting for 750 seats.

But what can states do about where the private sector chooses to open medical colleges? For any medical college to be opened, the state has to issue an “essentiality certificate”, which certifies that a college is needed. The idea is to prevent unhealthy competition. This raises the question of why states producing more than enough doctors continue to hand out essentiality certificates.

The results are showing in Karnataka where many colleges are in the news for getting fake patients during inspections since they don’t have enough to meet the norms. Many colleges that are allowed to admit students in the first year or for a few years are then derecognised when they no longer meet the MCI norms.

In Karnataka and Kerala, doctors’ associations have warned the governments against starting medical colleges as the glut of doctors is leaving many unemployed.

New private colleges opening creates another problem. The essentiality certificate guarantees if the new college is disallowed admissions by the MCI in a subsequent year, the state government will take over responsibility for students already admitted. This has two effects. First, students who did not get into the much sought after government colleges get entry through the back door. Second, the teacher-student ratio takes a hit at these colleges.

Density of doctors: 2017

From: Rema Nagarajan, 6 states have more docs than WHO’s 1 doc/1k people norm, September 2, 2018: The Times of India

Yet Rural Areas Remain Underserved

Even as governments cite shortage of doctors to allow more private medical colleges, six states — Delhi, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Punjab and Goa — have more doctors than the WHO norm of one for 1,000 people. Yet, some can’t find enough doctors for rural public health system. Also, most doctors from these states are unwilling to move to states like Bihar or UP that suffer from an acute shortage. This again raises the question of whether merely producing more doctors can address the crunch in public health and in rural areas.

The density of doctors per 1,000 people in Tamil Nadu is as high as 4, almost at the same level as countries like Norway and Sweden, where it is 4.3 and 4.2 respectively. In Delhi, the density is 3, higher than the UK, US, Canada and Japan, where it ranges from 2.3 to 2.8. In Kerala and Karnataka, the density is about 1.5 and it is about 1.3 in Punjab and Goa.

TOI calculated these densities after deducting 20% from the number of registered doctors, as is done by the Medical Council of India to estimate the number of doctors available, since many state councils have not updated their registries. In states that have updated them through periodic reregistration, as in Delhi, the 20% reduction was not applied.

Since India’s doctors are largely concentrated in urban areas, it is possible that even some states with doctor population ratios better than 1:1,000 may have shortages in rural areas. However, Tamil Nadu and Kerala boast that they have no vacancies in their rural public health systems.

According to Dr Prabhakar DN, former president of the Karnataka branch of the Indian Medical Association, 40% of doctors in Karnataka are in Bangalore. “In rural areas, there is still a shortage. Bangalore is saturated, even for specialists. So they don’t get jobs. Doctor salaries are coming down... We need to focus on producing doctors for the periphery. Just producing more doctors won’t work,” he added.

“Unlike engineers, who typically need to find jobs, doctors can be self-employed. If there are too many in a geographical area, they resort to unethical practices on the few patients they get to make ends meet. That’s why there is a need to calibrate the number being produced. We have told the state government to stop allowing the opening of more private colleges. They should shut down many of those that are in a bad shape, with no patients and no money to pay their faculty. The IMA is having to intervene each time to help them as they are not paid for six to eight months,” said Dr N Sulphi, secretary of the Kerala IMA.

MCI list, 2018: outdated but has historical nuggets

MCI Record Not Up To Date, Lists Even Those Who Registered In 1915

How many doctors does India have? Going by data given to Parliament by the Medical Council of India (MCI), there are more than 10.8 lakh doctors registered. In reality, no one really knows as is evident from the MCI’s own answer that 80% availability has to be assumed from this total number.

Why 80% and not 90% or 75%? A look at the Indian Medical Registry (IMR) makes it clear why no one knows exactly how many doctors are alive and practicing. Here are a few examples of doctors found in the registry.

Dinabandhu Basak, who qualified as an LMF (licenciate of medical faculty) from the University of London in 1895, and registered with the West Bengal Medical Council in 1915; Surendra Chandra Majumder, LMP (licenciate in medical practice) from Dibrugarh University in 1907, who registered with the Assam Medical Council in 1920; Shashi Bhushan Dutta, LMS (licenciate in medicine and surgery from Calcutta University in 1911, registered in 1918 with the Bihar Medical Council; Captain Christian Salvadore, MBBS from Kerala University in 1914, registered with the Travancore council in 1945; Y Sheshachalam, LMP from Madras University in 1916, registered in 1955 with the Andhra Pradesh council.

Over 75,000 of the doctors in the IMR registered before independence or a little after it, some as early as the 19th century as the examples given show. It seems safe to assume that a majority of them are dead or not practicing any more. Yet their names remain on the register and are counted year after year. Repeated directions since at least 2009 to state councils to re-register all doctors to weed out those who might have died, migrated, or stopped practicing have yielded little or no result.

One council with a live register is the Delhi Medical Council. But in this case, the data given to Parliament shows just 16,833 doctors registered in Delhi while the DMC itself says there are over 64,000. DMC president Dr Arun Gupta explained: “We have 48,657 re-registrations and 15,720 first-time registrations. Thus a total of 64,377 doctors registered with our council. So we have a fairly good idea of the actual number of doctors in Delhi.”

Unlike Delhi, MCI says many states like Haryana, Bihar, Orissa and Karnataka have not sent it the registration data for several years. “The State Medical Councils are established under an Act of the respective state legislatures. They are independent statutory authorities and MCI does not enjoy any supervisory role or control over them,” explained MCI President Dr Jayshree Mehta. According to the Indian Medical Council Act of 1956, under which the MCI is constituted, it is the statutory duty of the council to maintain the IMR. The Act also mandates state councils to supply MCI with a copy of their registers after April 1 of each year with all additions and amendments.

As a result, year after year, Parliament is given the same meaningless data without any effort by the health ministry, MCI or state councils to clean it up. Why does this matter? The health ministry calculates the shortage of doctors based on this data. In the age of Digital India and Aadhaar, it seems inexplicable that the government is unable to maintain a database of barely 10 lakh doctors.

Last year, the MCI had tried to initiate a system of Unique Permanent Registration Number (UPRN) for every doctor to be able to track them in cases of medical negligence, to get a clearer picture of how many doctors are practicing in India and to tackle the menace of fake doctors or ones with unrecognised degrees. The fact remains that over 60 years after it came into existence, the MCI has been unable to do the basic function of getting the IMR right.

Actual numbers: MCI vs. state councils

From: Rema Nagarajan, State councils blame MCI for mess in data on doctors, August 16, 2018: The Times of India

Several State Medical Councils have expressed shock at the Medical Council of India (MCI) submitting outdated and wrong data to Parliament year after year.

According to the officebearers of these councils, they have been sending updated lists to the MCI but do not see it reflected in the Indian Medical Register (IMR). Maintaining the IMR is one of the fundamental and statutory duties of the MCI.

While the MCI told TOI the state councils were to blame for not regularly sending information on registered doctors to it, most state councils refuted this allegation.

In the case of Karnataka, for instance, the MCI data submitted to Parliament recently showed 1.04 lakh doctors registered. The data MCI gave TOI also said the state council had not submitted any data in 2015 or 2016. However, the state council insisted it has been submitting data every quarter. The Karnataka Medical Council started the process of re-registration of doctors every five years in 2013 and after renewal had about 123,436 doctors in the registry as of March 2018, nearly 20,000 more than the MCI data shows.

“It is disrespect to Parliament to not make any effort whatsoever to give the latest data and not even explain to Parliament that the data being submitted has not been updated,” said KMC president, Dr H Veerbhadrappa.

The Maharashtra Medical Council (MMC) has not only done the process of reregistration of doctors every five years, the entire list of 86,567 doctors registered with it is available on the council’s website. “We have the most modern system. The revalidated data has been shared with the MCI, but it is still not reflected in the IMR,” said MMC president Dr Shivkumar S Utture. The MCI data shows 1.59 lakh doctors in Maharashtra, nearly twice as many as the state council’s number.

The MCI responded to the state councils’ claims by insisting the Karnataka figures it had put out were correct and that in Maharashtra’s case the state council had submitted no data for 2016 and data in a “wrong format” for 2017 only this month. It said, “as per the office records, we assure you that no wrong information has been submitted to the parliament.”

Since Karnataka and Maharashtra have a large number of medical colleges, they have many out-of-state students registering with these councils immediately after completing MBBS. But then they take no objection certificates (NOC) and go to their respective states. The NOCs issued are tracked and the names are removed from the register.

“Even office-bearers of the Travancore-Cochin Medical Council that registers all doctors in Kerala, who have sent their details to the MCI so many times find their names have not yet been included in the IMR. Then you can imagine just how well they are maintaining the database,” pointed out Dr VG Pradeep Kumar, vice-president of the council.

STATE-WISE

Delhi, 2019: a shortage in govt. hospitals

From: Abhinav Garg, Durgesh Nandan Jha, Lack of doctors puts Delhi's hospitals on life support, April 5, 2019: The Times of India

A status report filed by the state government in Delhi high court says there is an acute crisis of manpower in Delhi’s state-run hospitals. For instance, in GB Pant Hospital, the largest of the government’s super-specialty institutions, 159 posts for doctors are vacant, while the paramedical/nursing and non-medical strengths are short by199 and 233, respectively.

The situation in LNJP, Deen Dayal Upadhyay, Ambedkar and Guru Tegh Bahadur hospitals, among the biggest tertiary care centres in Delhi, are not reassuring either. The status report says that in LNJP, there are 41 vacancies among doctors, 15 among paramedical staff and 229 among the non-medical staff. Hospital sources said the figure for doctors related only to non-teaching specialists.

The report was filed in response to the persistent queries of the bench of chief justice Rajendra Menon and justice V K Rao, which had sought to know last year about the specific steps taken by the government to improve health facilities. The bench is hearing a PIL filed by Madhu Bala, a schoolteacher in Karawal Nagar who lost her baby after admission to GTB Hospital for delivery.

Bala’s lawyer Prashant Manchanda alleged in the petition that the hospital’s woeful infrastructure and lack of medical facilities were behind the loss of the baby and the near death of his client. He claimed the hospital did not perform a crucial surgery pleading “non-availability” of an OT. The petition urged the high court to step in “to immediately resurrect the dangerously dilapidated health system in public hospitals and utilise huge funds to infuse instant course correction and overhauling to prevent further health hazards”.

To begin with, the concerned court demanded details of the “infrastructural facilities available, the requirement of manpower for running of the hospitals and various other issues like functioning of equipment, installation of necessary equipment for treating the patients, etc” at the five hospitals. It directed the government to furnish information on life-saving equipment, drugs, beds, operation theatres and staff, among others. However, at the previous hearing, the court asked for more details as it was not satisfied by the data furnished by Delhi government’s Director General of Health Services on behalf of the hospitals.

“The real crisis is the depleted nursing staff and technicians. There have been occasions when surgeries had to be postponed due to the unavailability of nursing orderlies and safai karamcharis,” admitted a doctor at LNJP, who did not want to be quoted.

According to information furnished by the hospital, there are 436 sanctioned posts for safai karamcharis, of which 167 are currently vacant. There are no x-ray attendants, and the number of operation theatre attendants is also half the sanctioned strength.

In DDU Hospital, the largest government hospital in west Delhi and visited by over 4,000 patients daily, the data compiled by the government and shared with the high court shows a quarter of the posts of regular doctors in the 640-bedded hospital is vacant. The vacancy among the resident doctors and nursing staff is 15% and 10%, respectively.

Kerala has 3.3 times as many doctors as WHO norm/ 2019

From: Preetu Nair, In Kerala’s ‘sick’ hospitals, doctors are first casualty, March 21, 2019: The Times of India

State Has A Doc-Population Ratio Of 1:300 While WHO Prescribes 1:1000

Wedged between corporate hospitals with deep pockets and a vastly improved public healthcare system, mid-level private hospitals across Kerala are either not paying their doctors on time or forcing them to accept drastic pay cuts. In some hospitals, they are even retrenching doctors. The most affected are 50 to 100-bed hospitals. Of the 23 private medical colleges, about five are at present paying their doctors on time.

“It’s true that many hospitals are unable to pay doctors on time. Even senior specialist doctors are affected”, Indian Medical Association (IMA) state secretary Dr N Sulphi said. According to IMA Kerala estimates, of the 800-odd 50 plus-bedded healthcare institutions, around 100 hospitals are facing financial crisis and unable to pay doctors’ salaries.

Ironically, Kerala’s remarkably high doctor-topopulation ratio — WHO prescribes a doctor-population ratio of 1:1000, while in Kerala the ratio is 1:300 — could be at the root of the problem. There are around 70,000 doctors registered with Travancore Cochin Medical Council , of around 55,000 are practicing in Kerala. Of the 55,000, almost 50% are specialist doctors and get an average Rs 1.25 lakh to Rs 1.5 lakh salary per month. The around 1,200 super-specialist doctors in the state get anything between Rs 2.5 lakh and Rs 3 lakh per month. In a good hospital that has been in existence for more than 4 to 5 years, the doctor’s salary constitutes 20% of the total cost.

“Some are even forced to take a salary cut while taking a new job,” Dr Sulphi said. With almost 60% to 70% of doctors working as consultants, they don’t even have proper leave facility. There are no social security measures in place. With more doctors losing jobs, IMA has intervened and asked hospitals to at least honour contracts.

“We spend crores to set up speciality units but often doctors are unable to live up to the expectation and we don’t even get enough money to repay loans. Then we either have to reduce doctor’s salary or close down the unit,” said Kerala Private Hospitals Association (KPHA president Dr PK Mohamed Rasheed.

Kerala state planning board member Dr B Eqbal said, “With facilities in the government hospitals improving, people are opting for government hospitals. From just 25% patients availing services at government hospitals in the past, now it is jumped to 40%”.

Court judgements

2018: HC fines doctors ₹5,000 for poor handwriting

Ravi Singh Sisodiya, October 4, 2018: The Times of India

‘ILLEGIBLE WRITING OBSTRUCTION TO COURT WORK’

Poor handwriting of doctors are not really surprising, but a court in Uttar Pradesh has put that on record now.

A Lucknow bench of Allahabad high court has imposed Rs 5,000 penalty each on three doctors in separate cases for their illegible handwriting.

In the three criminal cases that came up for hearing last week, the injury report of the victims issued by hospitals from Sitapur, Unnao and Gonda district hospitals were “not readable” because the handwriting of the doctors who had issued them were “very poor”.

The bench considered it an obstruction in the court work and summoned the three doctors — Dr TP Jaiswal of Unnao, Dr PK Goel of Sitapur and Dr Ashish Saxena of Gonda. A bench of Justice Ajai Lamba and Justice Sanjay Harkauli admonished them and asked them to deposit Rs 5,000 penalty in the court’s library.

The doctors pleaded they erred in writing legible prescriptions as they were overburdened.

The court further directed principal secretary (home), principal secretary (medical & health) and director general (medical & health) to ensure that in future, medico reports are prepared in “easy language and legible handwriting”. The court also suggested that such reports should be computer-typed.

“The medico-legal report, if given clearly, can either endorse the incident as given by the eyewitnesses or can disprove the incident to a great extent. This is possible only if a detailed and clear medico-legal report is furnished by the doctors, with complete responsibility,” the bench observed.

It added, “The medical reports, however, are written in such shabby handwriting that they are not readable and decipherable by advocates or judges. It is to be considered that the medico-legal reports and post-mortem reports are prepared to assist the persons involved in dispensation of criminal justice. If such a report is readable by medical practitioners only, it shall not serve the purpose for which it is made.”

The court reminded the doctors of a circular issued by UP director general (medical & health) in November 2012 which stipulated doctors to prepare medico-legal reports in readable for m.

Emoluments

As in 2020?

From: Hemali Chhapia, Delhi, UP pay resident docs most, interns in Maha among worst paid, June 8, 2020: The Times of India

Delhi, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar pay resident doctors (MBBS degree holders pursuing postgraduation) the most. Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Gujarat and Haryana are also among the better paymasters for doctors at different levels in government-run hospitals. Interns (those in the final year of their MBBS course) in Maharashtra are among the worst paid even after a recent hike; only three other states, Rajasthan, MP and UP, pay lower. And specialists – senior residents pursuing a superspecialty course – are better off in the rural parts of Chhattisgarh, Haryana and UP where they earn Rs 1 lakh to 1.5 lakh a month, compared to Maharashtra where they get an average Rs 59,000.

Interns at Centre-run hosps get highest pay

At a time when resident doctors across the country are on the frontlines attending to Covid-19 patients, there is wide variation in their stipend depending on which part of India they serve. Chhattisgarh pays the maximum. UP, Bihar, Jharkhand, Haryana, all pay Rs 80,000-Rs 1 lakh a month while Maharashtra and the southern states lie in the mid-range, paying a monthly stipend of Rs 40,000-Rs 60,000. The Medical Council of India plans to make stipend post-MBBS uniform across the country, but the plan is yet to be cleared by all states.

Interns posted in central government-run hospitals are paid the highest, Rs 23,500 a month. Across India in staterun hospitals, their stipend varies from as low as Rs 7,000 in Rajasthan to the highest in Karnataka now at Rs 30,000. Medical interns are students who have completed four-anda-half years at a med school and do their compulsory rotational residential internship at a hospital attached to the medical college before getting the MBBS degree.

While interns in Maharashtra get a stipend of Rs 6,000, it was recently hiked to Rs 11,000 by the state. But BMC hospitals in Mumbai are yet to effect the change. Residents and senior residents in the state get Rs 54,000 and Rs 59,000, respectively (average of three years). The BMC recently announced a temporary stipend of Rs 50,000 for MBBS interns for their work in the Covid-19 wards. But a permanent increase of Rs 10,000 is expected for residents, said the head of the Directorate of Medical Education and Research in Maharashtra Dr T P Lahane.

At the postgraduate level, the stipend varies for every state as also for each year of the resident. In some states, there are multiple scales; to attract talent, the stipend offered to residents in rural areas is higher compared to what is paid in urban centres. For instance, in Chhattisgarh, residents in rural areas are paid Rs 20,000-30,000 more and seniors are paid Rs 1.5 lakh as compared to their counterparts in city hospitals who take home Rs 1.3 lakh a month. One of the reasons Bihar, UP, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand pay government doctors much higher, experts say, is because of the dependence on the public healthcare network in these states as compared to Maharashtra, TN or Karnataka, which have more hospitals driven by charitable trusts and private practitioners.

Founder member of Alliance of Doctors for Ethical Healthcare Dr Babu KV has for long been writing to the MCI for a uniform stipend for interns, residents and seniors.

Health issues

Kerala doctors die earlier than general public

Nov 20, 2017: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

Doctors in Kerala are dying younger when compared to the general public according to a study conducted by Indian Medical Association.

Majority of doctors in Kerala die due to cardio-vascular diseases and cancer.

Life expectancy of an Indian is 67.9 years and that of a Malayali is 74.9 years, the mean ‘age of death’ for a Malayali doctor is 61.75 years

Doctors heal and help people live longer, but it seems many of them are dying younger when compared to the general public in Kerala. A study conducted by research cell of the Indian Medical Association (IMA) in Kerala found that a majority of them die due to cardio-vascular diseases and cancer.

While the life expectancy of an Indian is 67.9 years and that of a Malayali is 74.9 years, the mean 'age of death' for a Malayali doctor is 61.75 years, said the study. "We were surprised by the figures as we expected doctors to live longer as they know what is good for them," said IMA research cell convener Dr Vinayan KP.

For the 10-year study - titled Physician's Mortality Data from 2007 to 2017 - the mortality pattern among doctors enrolled with state IMA's social security scheme was analysed. Of the 10,000 doctors who were part of the contributory supportive scheme that provides a fixed amount to deceased doctor's family, 282 died during the study period.

Of this, 87% were men and 13% women. Almost 27% died due to heart diseases, 25% due to cancer, 2% died due to infection and another 1% committed suicide.

The study didn't look at the reasons for early death, but doctors reasoned that stress was a major contributor. "Doctors are generally working under a lot of stress irrespective of government or private jobs. Increased working hours, the patients they attend to and high expectations contribute to this increased stress. Their working hours need to be fixed, besides government social security scheme. Also doctors should be prepared for periodic health check-ups," said IMA's former president Dr VG Pradeep Kumar.

"Being a doctor in India is injurious to one's health now. Due to stress, doctors are more prone to heart disease, diabetes and even paralysis," said IMA national president Dr KK Aggarwal. While IMA's national study showed that doctors were dying on an average 10 years earlier than the general population; in Kerala - a state with high life expectancy -they die nearly 13 years earlier.