Supreme Court: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.

|

The collegium system

Centre will amend Constitution to scrap collegium

Dhananjay.Mahapatra @timesgroup.com New Delhi:

The Times of India The Times of India Jul 26 2014

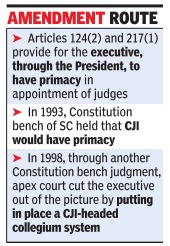

The judge-appointing-judge system was devised by the SC through two judgments in 1993 and 1998.

There is ambiguity vis-a-vis the constitutional provisions on the appointment of judges and the present practice.

Two articles provide that the executive, through the President, would have primacy in appointment of judges. This is how it was till 1993, when a constitution bench of the Supreme Court held that the CJI would have primacy in appointment of judges.

Article 124(2) says, “Every judge of the Supreme Court shall be appointed by the President by warrant under his hand and seal after consultation with such of the judges of the Supreme Court and the high courts in the states as the President may deem necessary for the purpose...“

Apex court's judgments stripped exec of any say in judge selection

Article 124(2) of the Constitution also provides that “in the case of appointment of a judge other than the Chief Justice, the Chief Justice of India shall always be consulted“. For appointment of a high court judge, Article 217(1) mandates the President to consult the CJI, governor of the state and chief justice of the HC.

Five years after a Constitution bench of the Supreme Court held that the CJI would have primacy in appointment of judges, in 1998, another Constitution bench judgment stripped the executive of any significant say in the appointment of judges to constitutional courts by devising the CJI-headed collegium system.

The scheme, which has been called judicial usurpation by others but justified by judges by invoking judicial independence, has lately been under the scanner for opaqueness.

So much so that former CJI J S Verma, author of one of the judgments by which the judiciary conferred upon itself the right to appoint judges, sought a review.

Efforts of the executive to do away with the collegium system began under UPA but failed to fructify. While in opposition, BJP supported the move but demanded that the Judicial Appointments Commission, which is proposed to select judges, should be fortified with a constitutional amendment in view of a likely challenge in judiciary .

It reiterated its support for JAC after coming to power, retired SC judge Markandey Katju about a former CJI giving in to political pressure to extend the tenure of a “corrupt“ judge is likely to provide fresh justification for its plans.

The Judicial Appointments Commission Bill, 2013 proposes replacing the collegium with a six-member panel headed by the CJI and comprising two SC judges, the law minister and two eminent citizens as its members.

The bill provides for selection of eminent citizens through another high-level committee comprising the Prime Minister, the CJI and the leader of opposition in Lok Sabha.

A parliamentary standing committee examined the bill and recommended that the JAC panel, headed by the CJI, should be a seven-member committee instead of six as proposed. It had suggested that three eminent persons be included in the panel instead of two proposed in the bill, with one of them either a woman or from the minority community or from SC/ST community.

Collegium system failed: Law panel chief

Law commission chairman Justice A P Shah said THE collegium system’s conduct has been opaque and that appointments to higher judiciary lacked transparency.

The collegium system is so opaque that even if someone wants to speak out, he cannot do it having come through the same system, he said. “The collegium system has completely failed, judges are appointed on unknown criteria,“ Justice Shah said, calling the apex court system of appointing judges as a cabal. “It has failed as favourites get appointed and the rest are left out,“ said the former chief justice of Delhi HC. He pointed out that the collegium had gone ahead to appoint a judge at the age of 60 years when the criteria clearly says any appointment to higher judiciary has to be below the age of 55.

2014: Collegium system ends

BENCH PRESS Dec 28 2014

MANOJ MITTA

The 21-year-old system of judges appointing themselves was scrapped in 2014, sparking fears of a decline in judicial independence On the historic day of May 16, 2014, when BJP became the first party in 30 years to win a clear majority in national elections, there was another significant development. It was the Supreme Court judgment passing strictures on the Gujarat government -specifically the home minister, who was Narendra Modi himself -while acquitting all the six accused for the Akshardham terror attack which had taken place barely six months after the post-Godhra riots. As it happened, within three months of the Akshardham judgment, the government pushed through a constitutional amendment stripping the judiciary of its “primacy“ in appointments to the SC and high courts.The 99th constitutional amendment Bill and the accompanying legislation, the national judicial appointments commission Bill, are set to dilute the powers that the SC appropriated for itself and the high courts through a controversial reinterpretation of the Constitution in 1993.

The new system of judicial ap pointments, which has restored the executive's say in the matter and opened up the process to two “eminent persons“ from outside, will come into force when at least 15 state assemblies endorse this far-reaching change. In place of the collegium consisting only of judges, the commission will have judicial and nonjudicial members in equal measure.Besides the Chief Justice of India (CJI) and two senior SC judges, the commission will have the law minister and the two eminent persons nominated by a panel consisting of the Prime Minister, CJI and the opposition leader in the Lok Sabha.

Though several from the opposition ranks and the bar have attacked it as an erosion of judicial independ ence, the circumstances were propitious for the government to make a strong case for doing away with, what has long been reviled as “a selfperpetuating oligarchy“. The credibility of the judiciary had been hit by a series of scandals -concerning probity and sexual misconduct -even prior to the formation of the Modi government.

The first clash under the new dispensation was on the collegium's recommendation to ap point senior advocate Gopal Subramanium to the SC. Departing from the practice of going by IB reports, the govern ment blocked Subrama nium's candidature on the basis of an adverse input from the CBI. This provoked a controversy as it was seen as a politically motivated move to keep away Subramanium on account of his role as amicus curiae in the Sohrabuddin fake encounter case. It was on his report that the SC had ordered a CBI probe leading to a charge-sheet being filed against Gujarat police officers as well as Amit Shah in his capacity as minister of state for home.

But the next flashpoint helped the government gain a moral edge over the judiciary. It was a blog written by former SC judge Markandey Katju alleging that, when he had been chief justice of the Madras high court, his attempt to get rid of a corrupt judge had been thwarted by then CJI, RC Lahoti. Detailing a murky sequence of events, Katju wrote that despite receiving an adverse report from the IB, Lahoti gave in to pressure from the Congress-led coalition government which in turn wanted the corrupt judge to be spared at the instance of its ally DMK. Though Lahoti denied this, Katju's blog put the judiciary on the defensive as it was evidently based on inside knowledge.

Katju went on to write that in response to another complaint of his against an Allahabad high court judge, the then CJI, SH Kapadia, had ordered tapping of telephones. Kapadia too denied Katju's contention.A day after Kapadia's denial on August 11, the then CJI, RM Lodha, erupted in court saying that there was “a misleading campaign against the judiciary to bring it into disrepute“. The provocation was a petition questioning the reported elevation of a Karnataka high court judge, KL Manjunath, as chief justice of the Punjab and Haryana high court despite the objections raised by an SC judge. The government's decision to return Manjunath's file underscored the fragility of the collegium system.

The succession of such events was enough for the government to garner enough support in both Houses to make the long-awaited breakthrough on judicial appointments. There was an interesting epilogue to this institutional battle, a month after passage of the Bills. A Constitution bench headed by Lodha stopped an executive intrusion into the judicial domain by striking down the national tax tribunal Act 2005. But the growing strength of the executive in 2014 has triggered fears of a parallel decline in judicial independence.

The collegium system undermined the efficiency of courts: Centre

The Times of India, May 09 2015

Collegium aids favouritism: Centre

Dhananjay Mahapatra

The government kept up its offensive against the judiciary's monopoly in the appointment of judges by saying that the collegium system worked like a huge favour-dispensing scheme which undermined the efficiency of courts. Supplementing attorney general Mukul Rohatgi's belligerence in seeking reference of petitions challenging validity of the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) to an 11-judge bench, solicitor general Ranjit Kumar was blunt when he said on Friday , “The collegium system has done little to strengthen independence of judiciary . It has created intra-dependence among the judiciary .“

Arguing before a bench of Justices J S Khehar, J Chelameswar, Madan B Lokur, Kurian Joseph and Adarsh Goel, Kumar said the collegium's choices were thrust upon chief justices of high courts as fait accompli. For appointments to high courts, the collegiums comprised the CJI and three senior-most judges of the Supreme Court.

The SG said, “I am not taking any name though I have at least 20 such examples. In 1993, the SC appropriated the power to appoint judges from the executive. It is not for judicial independence but intra-dependence. There is a former chief justice, who became an SC judge, who had said `I have to obey my masters to appoint judges in the HC because I want to go to Supreme Court'.“

The startling allegation came just before the bench broke for lunch and that was the reason why there was no response to it from the court.But if the SG's charges are true, it means there was an unwritten quid pro quo in judges' appointment -the chief justices of HCs blindly agree to the choices of the collegium to improve their chances for elevation to the Supreme Court.

Kumar said, “The collegium system has no transparency and lacks accountability. In contrast, the National Judicial Appointments Commission, brought in by a constitutional amendment, has the necessary checks and balances. NJAC will strengthen the independence of judiciary .“

Attorney general Mukul Rohatgi said the problem faced by a few additional judges, whose two-year tenure could come to an end during pendency of the challenge to NJAC's validity , should not deter the court from referring it to an 11-judge bench. “I am ready for an interim order from the court on the issue to protect the additional judges,“ he said.

“What is the hesitation in referring the matter to an 11judge bench? It is a matter of huge importance,“ the AG said. But the bench retorted, “AG, you please don't start deciding how many judges should hear the matter.“

Collegium appointed many inefficient judges: Centre

The Times of India, Jun 11 2015

AmitAnand Choudhary

A day after Supreme Court spoke out against the Centre's “hit-andtrial“ method of appointing judges -in a reference to the replacement of the old SC collegium system with the National Judicial Appointments Committee -attorney general Mukul Rohatgi on Wednesday told the SC that the collegium had appointed many undeserving and inefficient judges to the apex court and high courts who went on to create havoc in the country . Rohatgi submitted in a closed envelope a list of eight cases of what he called “bad appointments and selection“ at the instance of the SC collegium. The attorney general followed that up by referring to what he called questionable conduct by many judges, including three in Supreme Court, as he argued that the notion that only judges could appoint good judges was a “myth“.

He referred to a recent case of a Madras HC judge threatening to initiate contempt proceedings against the chief justice of the court, and asked why action had not been taken against him by the SC, which should have barred him from handling cases. “Havoc is being created in the country due to appointment of such judges.One bad fish can spoil the whole pond,“ the AG said. Attorney general Mukul Rohatgi on Wednesday cited what he called “bad appointments and selection“ of judges, in response to a five-judge Constitution bench headed by Justice J S Khehar asking the government to back up its contention against the collegium by citing instances of bad choices.

Rohatgi referred to the truancy of a former SC judge who generated headlines for lack of punctuality and could hold hearings only in afternoons. The judge used to come late even in the high court but still the collegium recommended his elevation to the SC. “This was the habit going on for the last ten years when the judge was in HC. If such was the track record then how was the judge promoted to the Supreme Court.This is not a rare single case of judicial indiscipline; many judges in various high courts come late and refuse to take up cases after lunch but the judiciary didn't take action against them,“ the AG said, adding that the government did not raise the issue as it would have been termed as interference in the independence of judiciary .

Rohatgi also pointed out that The Times of India was threatened with contempt of court for writing about the judge's lack of punctuality . Significantly , Fali S Nariman, the noted constitutional lawyer who is opposing the government on NJAC, supported Rohatgi on this. The Bench, too, chose not to join issue with him, preferring to switch to a lighter note, saying, “They are lordship in the true sense.“

AG, however, remained serious and moved to cite two other examples of appointments to the apex court by the collegium. He recalled the case of a SC judge who, according to him, was seen as inefficient, and that of yet another whose observations and comments were seen as belittling the dignity of a Supreme Court judge.

Appearing before the bench, also comprising Justices J Chelameswar, Madan B Lokur, Kurian Joseph and Adarsh Kumar Goel, the AG said the collegium system was not following the principle of meritocracy resulting in inefficient judges being appointed at the expense of deserving candidates. Without taking any names, he said many judg es in the SC and various high courts were not following court decorum and discipline.

Rohatgi said in many cases the collegium did not take into account the merit of a person and decisions to recommend names were taken on the basis of extraneous considerations.He said a retired SC judge in his entire life as a judge in various HCs did not dispose of more than 100 cases, but was still appointed to the SC; he was now a member of a Commission. The AG said there were many deserving judges who had disposed of thousands of cases but were not being promoted. He said some radical thought was required to shake up the present judicial system and NJAC was a step to bring accountability and transparency in the system.

The bench agreed with his contention that collegium made mistakes, but said that could not be the only ground to replace it.

Collegium system has not worked well: SC

The Times of India, Jun 17 2015

The Supreme Court has acknowledged the collegium system of judges appointing judges, which Parliament has replaced with National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC), has not worked well, reports Dhananjay Mahapatra.“The (collegium) system is good, but the implementation has gone wrong,“ a fivemember SC bench said. P 11 Senior advocate Fali S Nariman, lead lawyer for petitioners questioning the constitutional validity of the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC), was made to face his own bitter criticism of the Supreme Courtdrafted collegium system for appointment of judges. Former solicitor general T R Andhyarujina and additional solicitor general Tushar Mehta cited excerpts from Nariman's autobiography `Before Memory Fades' to drive home the point that not only had Parliament and 20 states ratified the NJAC to re place the collegium system but Nariman, the lead opponent of NJAC, too was against the collegium system.

Nariman was the counsel who argued for petitioner `Supreme Court Advocates on Record' in the 1990s, leading to formulation of the collegium system by a nine-judge constitution bench. Prior to the collegium system, the executive appointed judges in consultation with the CJI.

In his book, Nariman had devoted an entire chapter to express disappointment at the working of the collegium system. He wrote, “I would suggest that the closed-circuit network of five judges should be disbanded.“

Nariman was unperturbed by the opponents' remarks. He told TOI he had made his views clear to the SC during initial arguments against the NJAC in which the primacy of judiciary in appointment of judges has been erased. He said he still felt the collegium system had not worked well. But that did not mean that the present form of NJAC was a good sub stitute, he said.

Collegium system good but implementation faulty : SC

The Times of India, Jun 17 2015

Dhananjay Mahapatra

AG submits list of bad appointments

During hearing of a bunch of petitions challenging the validity of the NJAC, the Centre and states have slammed the collegium's nontransparent and non-accountable manner of appointing judges to the Supreme Court and high courts. The attorney general even submitted a list of bad appointments to the five-judge Constitution bench hearing the matter.

“One is the (collegium) system itself. The other is the implementation of the system-provided procedure.The National Commission to Review Working of the Constitution headed by Justice M N Venkatachaliah had said when the collegium system was devised by the Supreme Court, it was hailed the world over as a unique and good system,“ the bench of Justices J S Khehar, J Chelameswar, Madan B Lokur, Kurian Joseph and Adarsh K Goel said. “So, the (collegium) system is good, but the implementation has gone wrong. That does not mean the system is bad,“ the bench said in response to senior advocate T R Andhyarujina's argument that evolution of the collegium system was neither legally justified nor had worked satisfactorily . The court pointed out that the qualification for `eminent person' did not specify whether they should be Indians.“Can a foreigner be appointed as eminent person in NJAC?“ the bench asked.

Mr Justice Cyriac Joseph

Mr Mukul Rohatgi’s arguments

The Times of India, Jun 20 2015

89 judgments in all of 115 pages: Rohatgi keeps up attack on judge

Attorney general Mukul Rohatgi ignited the sedate, academic arguments on the issue of NJAC's constitutional validity in the Supreme Court by reiterating his charge against former SC judge Justice Cyriac Joseph that he was miserly in authoring judgments. Rohatgi informed a fivejudge bench headed by Justice J S Khehar that Justice Joseph, while in Uttarakhand high court, had delivered 162 judgments. Of this, he produced copies of 89 judgments that together ran into 115 pages.

“These cannot be even called orders as they did not decide rights of the parties.These are merely stating that the petition has become infructuous or allowing the petition to be withdrawn. In Delhi high court, I know of a worse situation as I prac tised extensively when Justice Joseph was a judge. He had reserved more than 100 judgments and went out, on being transferred, without delivering the judgments, warranting re-hearing of the cases,“ Rohatgi said. Senior advocate Anil Divan shared the AG's impression.

“Of the 162 judgments, two could be called judgments as one ran into 15 pages and the other 27 pages. But both these judgments were authored by the other judge who was part of the bench headed by Justice Joseph,“ the AG said.

The court closed the chapter saying “we are not holding an inquiry into this“, and focused on arguments on petitions challenging the constitutional validity of National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC), which replaced the 20-year-old collegium system wherein judges selected judges for the SC and HCs.

Mr Fali S Nariman’s arguments

Fali S Nariman, had argued for lead petitioner Supreme Court Advocates-on Record Association and said states had ratified only the constitutional amendment and not the NJAC. Hence, the government could not legitimately claim that the NJAC had been ratified by states.

Moreover, the NJAC brought out significant changes in the procedure for appointment of judges and hence should have been a part of the constitutional amendment, he said. “By not making the NJAC procedure a part of the constitutional amendment, the government has played a fraud on the Constitution which gave a lot of importance to judicial independence,“ Nariman said.

Appearing for Bar Association of India, senior advocate Anil Divan said the NJAC had opened the door for political interference in the appointment of judges, which has consistently been regarded taboo, both by the Constitution-framers and during the long period of working of the Constitution.

He distinguished the NJAC from judicial appointment commissions working in other countries, and said even in the UK, the selection process did not involve any minister or bureaucrat.

2014: Panel to pick judges

Jan 01 2015

The Supreme Court collegium system of appointing judges to the apex court and high courts got a burial with President Pranab Mukherjee giving his assent to the Judicial Appointments Commission Bill .

The bill has already been ratified by at least 17 states and many more are in the process of doing so, said a senior law ministry official. It is mandatory for a constitutional amendment bill after it is passed by both Houses of Parliament to be ratified by at least half of the states. This brings to an end a system which the apex court had put in place through a judgment in 1993 to do away with the earlier practice of the government appointing judges.

The process of replacing the collegium with a panel was initiated during the first NDA government through a bill in 2003 but it was never taken up by Parliament. After Modi took over, Ravi Shankar Prasad, law minister in the first NDA government, initiated the NJAC bill and pursued political parties to evolve a consensus. The government will shortly notify the new Constitutional amendment replacing the SC collegium with the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC). After the notification, the process of setting up of the NJAC will begin as provided under an enabling legislation which has been passed by Parliament along with the Constitution amendment bill.

The enabling NJAC bill provides for a six-member commission headed by the chief justice of India and comprising two senior SC judges as its members besides two eminent persons and the law minister. The two eminent persons in the commission will be appointed by a panel comprising the CJI, the Prime Minister and the leader of the largest opposition party in Lok Sabha. The NJAC also has provision for a veto where it provides that no name opposed by two or more of the six-member body can go through. The two eminent persons will have a tenure of three years and one of them would be from one of the following categories: scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, women or the minority community .

After the NJAC is set up, a name recommended for appointment as judge to the SC or high courts can be returned by the President for reconsideration. Though an initial recommendation to the President for appointment can be made by a 5-1 majority , this would not suffice to re-recommend the same name.

If a name is returned for reconsideration, the committee can reiterate the name only if there is unanimity among the members after reconsideration.

Appointment of judges: superior courts

Whatever the process, men of character must pick judges

LEGALLY SPEAKING –

The Times of India Jul 29 2014

Till 1993, judges were appointed to the Supreme Court and high courts by the President, read the Union government, after consulting the Chief Justice of India. The CJI seldom disagreed with the executive.

Two significant judgments dramatically altered the process. In 1993, a nine-judge bench in Supreme Court Advocates on Record Association case took away the executive’s primacy in appointment of judges and gave it to the CJI. In 1998, another nine-judge bench answered a presidential reference by laying down an elaborate procedure – the CJI-headed collegium system – to select and recommend to the government persons to be appointed as judges of the SC and HCs.

The executive was given the option of returning a name for the collegium’s reconsideration. If the name was re-sent, the executive was bound to appoint him. For the last 16 years, this judge-appoint-judge system has been in operation. Markandey Katju has experience of both the systems. He was appointed a judge of Allahabad High Court by the executive in 1991. But his later appointments -chief justice of Madras HC and transfer to Delhi HC and later as judge of SC in April 2006 – happened under the collegium system.

He often gave vent to his intolerance towards corruption. In March 2007, while sitting with Justice S B Sinha, he had said, “Everyone wants to loot this country. The only deterrent is to hang a few corrupt persons from the lamp post.

The law does not permit us to do it, but otherwise we would prefer to hang the corrupt.” Katju, who would have preferred instant Taliban style justice in the absence of limitations of law, strangely remained tight lipped for nearly a decade on a ‘corrupt judge’ continuing in Madras HC. His revelations have stirred a fresh debate on what would be the ideal process for appointment of judges to the SC and HCs? Both systems had their share of questionable products.

Two famous judges – Y V Chandrachud and P N Bhagwati – were appointed by the executive. They capitulated to political pressure much more gravely than Justice R C Lahoti, who was taken in by the then wily law minister H R Bhardwaj in 2005 and granted extension of service to a ‘corrupt judge” despite the collegium unanimously deciding not to continue with his services.

On April 28, 1976, a five-judge bench pronounced judgment in the ADM Jabalpur case and buried all fundamental rights, including the most fundamental among fundamental rights – the right to life – under political pressure of the Indira Gandhi regime which wielded draconian powers during Emergency. How on earth could a country survive without its citizens having the right to life? But the famous four – then CJI A N Ray and Justices M H Beg, Y V Chandrachud and P N Bhagwati – capitulated. They gave primacy to selfpreservation over preservation of citizens’ life.

Under tremendous political pressure and threat, Justice H R Khanna held his head high to record a dissent note saying right to life could never be suspended. He stood tall among the five, and is still standing tall in court number two of the Supreme Court. Khanna too was a product of the same system which had appointed the other four. Khanna valued life. The rewards of capitulation went to Justice Beg, who was appointed CJI by the Indira regime. If the government thought of humiliating Khanna by superseding him, it failed. He tendered his resignation. Khanna showed that a man’s character shines brightest in times of pressure and adversity.

The SC realized this six years later and spoke out in S P Gupta case [1982 (2) SCR 365].

“Judges should be stern stuff and tough fire, unbending before power, economic or political and they must uphold the core principle of rule of law which says ‘be you ever so high, the law is above you’,” it had said. Immortal words penned more than three decades ago, but seldom practiced.

Whatever process a political system devises for appointment of judges, it would lose its efficacy if it is manned by people who do not put country over self and place integrity above politics and posts.

As president of the Constituent Assembly, Rajendra Prasad, who went on to become the first President, had warned of this while moving for adoption of the Constitution in 1949.

He had said, “Whatever the Constitution may or may not provide, the welfare of the country will depend upon the men who administer it. If the people who are elected are capable and men of character and integrity, they will be able to make the best even of a defective Constitution. “If they are lacking in these, the Constitution cannot help the country, After all, a Constitution, like a machine, is a lifeless thing. It acquires life because of the men who control and operate it. And India needs today nothing more than a set of honest men who will have the interest of the country before them.”

Landmark shifts of stance

Case studies: Supreme Court’s landmark shifts

The apex court is rightly hailed for its stellar role. But little has been written about its dramatic shifts on a range of key issues. TOI brings you the untold story

Manoj Mitta

Raising a toast for the establishment of the Supreme Court as India turned into a Republic, C K Daphtary, who went on to become the first solicitor general, said in January 1950, “A republic without a pub is a relic!”

Jokes apart, no appraisal of the 60 years of the Indian Republic can ignore the stellar role played by the Supreme Court in maintaining the constitutional scheme of checks and balances. Equally, no appraisal of the Supreme Court can be complete without delving into the vagaries of its rulings, for better or for worse — especially because the shifts in its position have not always been for reasons beyond its control.

This somewhat awkward aspect has however received little attention, perhaps because of the reverence reserved for the higher judiciary. Here is an attempt to focus exclusively on the judicial shifts made by the Supreme Court through the 60 years of its existence on a range of key issues.

Somersault on due process

The first major constitutional issue decided by the Supreme Court came out of the preventive detention of communist leader A K Gopalan, in whose honour the headquarters of CPM is named. The issue was whether somebody’s detention could be justified merely on the ground that it had been carried out “according to the procedure established by law,” as stipulated in Article 21 of the Constitution. Or, would that procedure be valid only if it complied with principles of natural justice such as giving a hearing to the affected person?

In the A K Gopalan case of 1950, the Supreme Court, taking a narrow view of Article 21, refused to consider if the procedure established by law suffered from any deficiencies. Fortunately, three decades later, it took a 180 degree turn on this issue in the Maneka Gandhi case of 1978. The provocation was the arbitrary law that had allowed the Janata Party government to take away Maneka’s passport without any remedy. Importing the American concept of due process, the Supreme Court ruled that the procedure established by law for depriving somebody of their life or personal liberty had to be “just, fair and reasonable”.

Reduction of Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution

Validity of the very first constitutional amendment was challenged mainly because it had inserted the Ninth Schedule to insulate agrarian laws from being tested in courts. The issue facing the Supreme Court was to determine the extent to which Parliament could go while exercising its amending power under Article 368. This is how SC shifted its position more than once on this crucial issue.

First, in the Shankari Prasad case of 1951, it ruled that since no limits had been spelt out in Article 368, the power to amend the Constitution included abridgement of even fundamental rights.

Next, in the Golaknath case of 1967, it betrayed second thoughts on trusting Parliament with such unfettered discretion under Article 368. Since Article 13 stipulated that every law enacted by Parliament had to comply with fundamental rights, the Supreme Court read that limitation into constitutional amendments as well.

Finally, in the Kesavananda Bharati case of 1973, the SC held that the condition prescribed by Article 13 of complying with fundamental rights applied only to ordinary laws, not constitutional amendments. Taking the middle path, it said the only limitation on Article 368 was that a constitutional amendment could not alter the “basic structure” of the Constitution (such as the sovereignty of the country or its secular character).

Enlarging the scope of judicial review

For decades, the most abused provision of the Constitution was the sweeping power conferred on the President — in other words, the Central government — to dismiss a duly elected state government. The validity of actions taken under Article 356 of the Constitution went before the Supreme Court for the first time in 1977 when the then newly elected Janata Party government at the Centre had dismissedCongress governments in states for no reason other than the fact that it wanted to hold early elections.

But the Supreme Court, in what is known as the State of Rajasthan case of 1977, declined to intervene, ostensibly to avoid entering the political thicket. The President’s satisfaction that the state concerned could not be carried on in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution was, it said, not subject to judicial review. The apex court however reversed its stand in the S R Bommai case of 1994, where it held that a proclamation under Article 356 could be struck down if it was “found to be mala fide or based on wholly irrelevant or extraneous grounds”. Subjecting the President’s satisfaction to judicial review, the Bommai verdict clarified that the power conferred by Article 356 was a conditional one, not absolute.

Changing conception of compensation

Many a legal battle has been fought on the vexed issue of compensation payable to affected parties when a property has been acquired by the government. The question of interpreting the compensation promised by the Constitution arose for the first time in the Bela Banerjee case of 1954 involving a West Bengal law which sought to pay off the owners on the basis of the market value of their land on some distant date in the past. Rejecting the socialistic arguments of the state, SC laid down that the compensation should be “a just equivalent of what the owner has been deprived of”.

In a bid to get over the effect of the Bela Banerjee case, the Nehru government amended the Constitution stipulating that no law dealing with the manner in which compensation was to be given “shall be called in question in any court on the ground that the compensation by that law is not adequate”. This in turn triggered a chain of a vacillating judgments and another constitutional amendment on the compensation issue. It culminated in the shift from the categorical “just equivalent” in the Bela Banerjee case to a limp admission in the Kesavandanda Bharati case of 1973 that the amount need not be equivalent, so long as it was “not illusory”.

Diversity on quotas

Caste-based reservations in jobs and educational institutions are another contentious issue on which the Supreme Court has had to change its position in keeping with the times. Its initial response was completely adverse. In the Champakam Dorairajan case of 1951, the Supreme Court slammed caste-based reservations as a violation of the Constitutional prohibition of discrimination. It was however forced to take a more accommodative view of social justice once the Nehru government responded with the first constitutional amendment stipulating that the general prohibition of discrimination could not prevent the state from making any special provision for the advancement of SCs, STs and OBCs.

Having reconciled to the imperative of quota, the Supreme Court, in the M R Balaji case of 1963, imposed a cap of 50% on the extent of reservations for all the categories taken together, in a bid to ensure that the exception did not exceed the general rule of non-discrimination. Following the Mandal controversy, the Supreme Court, in the Indra Sawhney case of 1993, upheld the introduction of quota for OBCs in Central government jobs subject to the exclusion of the “creamy layer” (candidates whose parents are relatively wealthy or better educated).

Seasonal change on economic policy

True to its reputation of giving precedence to individual liberty over socialistic schemes, the Supreme Court, in the Bank Nationalization case of 1970, displayed no inhibition in probing the allegations that the Indira Gandhi’s government’s economic policy was discriminatory and deficient on compensation. As a corollary, it even struck down the nationalisation law.

But post-liberalisation, the SC, in the Balco case of 2001, upheld the Vajpayee government’s disinvestment policy by adopting the principle that “in the case of a policy decision on economic matters, the courts should be very circumspect in conducting any inquiry and must be most reluctant to impugn the judgment of the experts.”

Turning consultation into concurrence

This shift has earned the Supreme Court the opprobrium of turning the judiciary into a “self-perpetuating oligarchy”. For, all that the Constitution has prescribed in the appointment of judges to the Supreme Court is that the Chief Justice of India “shall always be consulted”.

Considering political fallout

When Supreme Court considered the political fallout of its verdict

Dhananjay Mahapatra The Times of India Jan 07 2015

The political fallout of a judicial decision has seldom bothered the judiciary, but it appears that in 2012 the Supreme Court delayed the judgment on the CBI's probe into disproportionate assets cases against the Samajwadi Party chief and his sons to await completion of assembly elections.

On March 1, 2007, just before the assembly elections, an SC bench headed by Justice A R Lakshmanan had ordered the CBI to probe into alleged disproportionate assets of Mulayam Singh Yadav and his sons on a PIL filed by Vishwanath Chatur-vedi. Justice Lakshmanan retired on March 21, 2007 and was immediately appointed as chair man of the Law Commission.

Yadavs filed petitions seeking review of the March 1, 2007 judgment questioning the jurisdiction of the SC to order CBI probe without the consent of the state government on a politically motivated petition.The review petitions were heard by a bench of Justices Altamas Kabir and H L Dattu, which reserved its judgment on February 17, 2011.

Internal communication between Justice Kabir and Justice Dattu, accessed by TOI, shows, among other things, the ground for delay in pronouncing the judgment was the possible political fal lout of its decision in this case.

In June 2012, Justice Kabir wrote to Justice Dattu: “I deliberately waited till after the UP elections to pronounce the judgment so that the level playing field was not disturbed.“ The UP Assembly elections were held between February 8, 2012 and March 3, 2012. SP swept the polls and Akhilesh Yadav became the chief minister.

Just days before the verdict on December 13, 2012, Justice Kabir sent the draft judgment to Justice Dattu for his approval. In the note attached to the draft judgment, Justice Kabir had referred to the CBI's flip-flops in the case and said, “This dual stand in the submissions of the highest investigating agency cannot be appreciated by this court.“

Justice Dattu agreed with Justice Kabir, who had by then become the Chief Justice of India, that the CBI stand had been confusing.However, he clarified that “while making submissions (on behalf of the CBI) it has been highlighted that substantial prima-facie elements are there to conduct an investigation“.

He also felt that there was no substantial evidence against Dimple Yadav and no further investigation needed to be carried out against her.But Justice Dattu was firm against quashing the entire proceedings regarding disproportionate assets. Justice Dattu wrote back: “As discussed with you, quashing of the entire proceedings regarding disproportionate assets, which is evident on the face of records, will not only be doing injustice but also create a political turbulence. We are directing only CBI probeinvestigation and not holding them guilty . If nothing is found, they are acquitted. But in fitness of things a thorough investigation is needed.“

The judgment on the review petitions was pronounced on December 13, 2012. The court held that the CBI probe into alleged disproportionate assets of Mulayam, Akhilesh, and Prateek Yadav as ordered by the SC on March 1, 2007 was justified.