Supreme Court: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.

|

Contents |

The collegium system

Centre will amend Constitution to scrap collegium

Dhananjay.Mahapatra @timesgroup.com New Delhi:

The Times of India The Times of India Jul 26 2014

The judge-appointing-judge system was devised by the SC through two judgments in 1993 and 1998.

There is ambiguity vis-a-vis the constitutional provisions on the appointment of judges and the present practice.

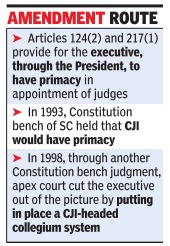

Two articles provide that the executive, through the President, would have primacy in appointment of judges. This is how it was till 1993, when a constitution bench of the Supreme Court held that the CJI would have primacy in appointment of judges.

Article 124(2) says, “Every judge of the Supreme Court shall be appointed by the President by warrant under his hand and seal after consultation with such of the judges of the Supreme Court and the high courts in the states as the President may deem necessary for the purpose...“ ==Apex court's judgments stripped exec of any say in judge selection ==

Article 124(2) of the Constitution also provides that “in the case of appointment of a judge other than the Chief Justice, the Chief Justice of India shall always be consulted“. For appointment of a high court judge, Article 217(1) mandates the President to consult the CJI, governor of the state and chief justice of the HC.

Five years after a Constitution bench of the Supreme Court held that the CJI would have primacy in appointment of judges, in 1998, another Constitution bench judgment stripped the executive of any significant say in the appointment of judges to constitutional courts by devising the CJI-headed collegium system.

The scheme, which has been called judicial usurpation by others but justified by judges by invoking judicial independence, has lately been under the scanner for opaqueness.

So much so that former CJI J S Verma, author of one of the judgments by which the judiciary conferred upon itself the right to appoint judges, sought a review.

Efforts of the executive to do away with the collegium system began under UPA but failed to fructify. While in opposition, BJP supported the move but demanded that the Judicial Appointments Commission, which is proposed to select judges, should be fortified with a constitutional amendment in view of a likely challenge in judiciary .

It reiterated its support for JAC after coming to power, retired SC judge Markandey Katju about a former CJI giving in to political pressure to extend the tenure of a “corrupt“ judge is likely to provide fresh justification for its plans.

The Judicial Appointments Commission Bill, 2013 proposes replacing the collegium with a six-member panel headed by the CJI and comprising two SC judges, the law minister and two eminent citizens as its members.

The bill provides for selection of eminent citizens through another high-level committee comprising the Prime Minister, the CJI and the leader of opposition in Lok Sabha.

A parliamentary standing committee examined the bill and recommended that the JAC panel, headed by the CJI, should be a seven-member committee instead of six as proposed. It had suggested that three eminent persons be included in the panel instead of two proposed in the bill, with one of them either a woman or from the minority community or from SC/ST community.

Collegium system failed: Law panel chief

Law commission chairman Justice A P Shah said THE collegium system’s conduct has been opaque and that appointments to higher judiciary lacked transparency.

The collegium system is so opaque that even if someone wants to speak out, he cannot do it having come through the same system, he said. “The collegium system has completely failed, judges are appointed on unknown criteria,“ Justice Shah said, calling the apex court system of appointing judges as a cabal. “It has failed as favourites get appointed and the rest are left out,“ said the former chief justice of Delhi HC. He pointed out that the collegium had gone ahead to appoint a judge at the age of 60 years when the criteria clearly says any appointment to higher judiciary has to be below the age of 55.

Appointment of judges: superior courts

Whatever the process, men of character must pick judges

LEGALLY SPEAKING –

The Times of India Jul 29 2014

Till 1993, judges were appointed to the Supreme Court and high courts by the President, read the Union government, after consulting the Chief Justice of India. The CJI seldom disagreed with the executive.

Two significant judgments dramatically altered the process. In 1993, a nine-judge bench in Supreme Court Advocates on Record Association case took away the executive’s primacy in appointment of judges and gave it to the CJI. In 1998, another nine-judge bench answered a presidential reference by laying down an elaborate procedure – the CJI-headed collegium system – to select and recommend to the government persons to be appointed as judges of the SC and HCs.

The executive was given the option of returning a name for the collegium’s reconsideration. If the name was re-sent, the executive was bound to appoint him. For the last 16 years, this judge-appoint-judge system has been in operation. Markandey Katju has experience of both the systems. He was appointed a judge of Allahabad High Court by the executive in 1991. But his later appointments -chief justice of Madras HC and transfer to Delhi HC and later as judge of SC in April 2006 – happened under the collegium system.

He often gave vent to his intolerance towards corruption. In March 2007, while sitting with Justice S B Sinha, he had said, “Everyone wants to loot this country. The only deterrent is to hang a few corrupt persons from the lamp post.

The law does not permit us to do it, but otherwise we would prefer to hang the corrupt.” Katju, who would have preferred instant Taliban style justice in the absence of limitations of law, strangely remained tight lipped for nearly a decade on a ‘corrupt judge’ continuing in Madras HC. His revelations have stirred a fresh debate on what would be the ideal process for appointment of judges to the SC and HCs? Both systems had their share of questionable products.

Two famous judges – Y V Chandrachud and P N Bhagwati – were appointed by the executive. They capitulated to political pressure much more gravely than Justice R C Lahoti, who was taken in by the then wily law minister H R Bhardwaj in 2005 and granted extension of service to a ‘corrupt judge” despite the collegium unanimously deciding not to continue with his services.

On April 28, 1976, a five-judge bench pronounced judgment in the ADM Jabalpur case and buried all fundamental rights, including the most fundamental among fundamental rights – the right to life – under political pressure of the Indira Gandhi regime which wielded draconian powers during Emergency. How on earth could a country survive without its citizens having the right to life? But the famous four – then CJI A N Ray and Justices M H Beg, Y V Chandrachud and P N Bhagwati – capitulated. They gave primacy to selfpreservation over preservation of citizens’ life.

Under tremendous political pressure and threat, Justice H R Khanna held his head high to record a dissent note saying right to life could never be suspended. He stood tall among the five, and is still standing tall in court number two of the Supreme Court. Khanna too was a product of the same system which had appointed the other four. Khanna valued life. The rewards of capitulation went to Justice Beg, who was appointed CJI by the Indira regime. If the government thought of humiliating Khanna by superseding him, it failed. He tendered his resignation. Khanna showed that a man’s character shines brightest in times of pressure and adversity.

The SC realized this six years later and spoke out in S P Gupta case [1982 (2) SCR 365].

“Judges should be stern stuff and tough fire, unbending before power, economic or political and they must uphold the core principle of rule of law which says ‘be you ever so high, the law is above you’,” it had said. Immortal words penned more than three decades ago, but seldom practiced.

Whatever process a political system devises for appointment of judges, it would lose its efficacy if it is manned by people who do not put country over self and place integrity above politics and posts.

As president of the Constituent Assembly, Rajendra Prasad, who went on to become the first President, had warned of this while moving for adoption of the Constitution in 1949.

He had said, “Whatever the Constitution may or may not provide, the welfare of the country will depend upon the men who administer it. If the people who are elected are capable and men of character and integrity, they will be able to make the best even of a defective Constitution. “If they are lacking in these, the Constitution cannot help the country, After all, a Constitution, like a machine, is a lifeless thing. It acquires life because of the men who control and operate it. And India needs today nothing more than a set of honest men who will have the interest of the country before them.”

Landmark shifts of stance

Case studies: Supreme Court’s landmark shifts

The apex court is rightly hailed for its stellar role. But little has been written about its dramatic shifts on a range of key issues. TOI brings you the untold story

Manoj Mitta

Raising a toast for the establishment of the Supreme Court as India turned into a Republic, C K Daphtary, who went on to become the first solicitor general, said in January 1950, “A republic without a pub is a relic!”

Jokes apart, no appraisal of the 60 years of the Indian Republic can ignore the stellar role played by the Supreme Court in maintaining the constitutional scheme of checks and balances. Equally, no appraisal of the Supreme Court can be complete without delving into the vagaries of its rulings, for better or for worse — especially because the shifts in its position have not always been for reasons beyond its control.

This somewhat awkward aspect has however received little attention, perhaps because of the reverence reserved for the higher judiciary. Here is an attempt to focus exclusively on the judicial shifts made by the Supreme Court through the 60 years of its existence on a range of key issues.

Somersault on due process

The first major constitutional issue decided by the Supreme Court came out of the preventive detention of communist leader A K Gopalan, in whose honour the headquarters of CPM is named. The issue was whether somebody’s detention could be justified merely on the ground that it had been carried out “according to the procedure established by law,” as stipulated in Article 21 of the Constitution. Or, would that procedure be valid only if it complied with principles of natural justice such as giving a hearing to the affected person?

In the A K Gopalan case of 1950, the Supreme Court, taking a narrow view of Article 21, refused to consider if the procedure established by law suffered from any deficiencies. Fortunately, three decades later, it took a 180 degree turn on this issue in the Maneka Gandhi case of 1978. The provocation was the arbitrary law that had allowed the Janata Party government to take away Maneka’s passport without any remedy. Importing the American concept of due process, the Supreme Court ruled that the procedure established by law for depriving somebody of their life or personal liberty had to be “just, fair and reasonable”.

Reduction of Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution

Validity of the very first constitutional amendment was challenged mainly because it had inserted the Ninth Schedule to insulate agrarian laws from being tested in courts. The issue facing the Supreme Court was to determine the extent to which Parliament could go while exercising its amending power under Article 368. This is how SC shifted its position more than once on this crucial issue.

First, in the Shankari Prasad case of 1951, it ruled that since no limits had been spelt out in Article 368, the power to amend the Constitution included abridgement of even fundamental rights.

Next, in the Golaknath case of 1967, it betrayed second thoughts on trusting Parliament with such unfettered discretion under Article 368. Since Article 13 stipulated that every law enacted by Parliament had to comply with fundamental rights, the Supreme Court read that limitation into constitutional amendments as well.

Finally, in the Kesavananda Bharati case of 1973, the SC held that the condition prescribed by Article 13 of complying with fundamental rights applied only to ordinary laws, not constitutional amendments. Taking the middle path, it said the only limitation on Article 368 was that a constitutional amendment could not alter the “basic structure” of the Constitution (such as the sovereignty of the country or its secular character).

Enlarging the scope of judicial review

For decades, the most abused provision of the Constitution was the sweeping power conferred on the President — in other words, the Central government — to dismiss a duly elected state government. The validity of actions taken under Article 356 of the Constitution went before the Supreme Court for the first time in 1977 when the then newly elected Janata Party government at the Centre had dismissedcongres governments in states for no reason other than the fact that it wanted to hold early elections.

But the Supreme Court, in what is known as the State of Rajasthan case of 1977, declined to intervene, ostensibly to avoid entering the political thicket. The President’s satisfaction that the state concerned could not be carried on in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution was, it said, not subject to judicial review. The apex court however reversed its stand in the S R Bommai case of 1994, where it held that a proclamation under Article 356 could be struck down if it was “found to be mala fide or based on wholly irrelevant or extraneous grounds”. Subjecting the President’s satisfaction to judicial review, the Bommai verdict clarified that the power conferred by Article 356 was a conditional one, not absolute.

Changing conception of compensation

Many a legal battle has been fought on the vexed issue of compensation payable to affected parties when a property has been acquired by the government. The question of interpreting the compensation promised by the Constitution arose for the first time in the Bela Banerjee case of 1954 involving a West Bengal law which sought to pay off the owners on the basis of the market value of their land on some distant date in the past. Rejecting the socialistic arguments of the state, SC laid down that the compensation should be “a just equivalent of what the owner has been deprived of”.

In a bid to get over the effect of the Bela Banerjee case, the Nehru government amended the Constitution stipulating that no law dealing with the manner in which compensation was to be given “shall be called in question in any court on the ground that the compensation by that law is not adequate”. This in turn triggered a chain of a vacillating judgments and another constitutional amendment on the compensation issue. It culminated in the shift from the categorical “just equivalent” in the Bela Banerjee case to a limp admission in the Kesavandanda Bharati case of 1973 that the amount need not be equivalent, so long as it was “not illusory”.

Diversity on quotas

Caste-based reservations in jobs and educational institutions are another contentious issue on which the Supreme Court has had to change its position in keeping with the times. Its initial response was completely adverse. In the Champakam Dorairajan case of 1951, the Supreme Court slammed caste-based reservations as a violation of the Constitutional prohibition of discrimination. It was however forced to take a more accommodative view of social justice once the Nehru government responded with the first constitutional amendment stipulating that the general prohibition of discrimination could not prevent the state from making any special provision for the advancement of SCs, STs and OBCs.

Having reconciled to the imperative of quota, the Supreme Court, in the M R Balaji case of 1963, imposed a cap of 50% on the extent of reservations for all the categories taken together, in a bid to ensure that the exception did not exceed the general rule of non-discrimination. Following the Mandal controversy, the Supreme Court, in the Indra Sawhney case of 1993, upheld the introduction of quota for OBCs in Central government jobs subject to the exclusion of the “creamy layer” (candidates whose parents are relatively wealthy or better educated).

Seasonal change on economic policy

True to its reputation of giving precedence to individual liberty over socialistic schemes, the Supreme Court, in the Bank Nationalization case of 1970, displayed no inhibition in probing the allegations that the Indira Gandhi’s government’s economic policy was discriminatory and deficient on compensation. As a corollary, it even struck down the nationalisation law.

But post-liberalisation, the SC, in the Balco case of 2001, upheld the Vajpayee government’s disinvestment policy by adopting the principle that “in the case of a policy decision on economic matters, the courts should be very circumspect in conducting any inquiry and must be most reluctant to impugn the judgment of the experts.”

Turning consultation into concurrence

This shift has earned the Supreme Court the opprobrium of turning the judiciary into a “self-perpetuating oligarchy”. For, all that the Constitution has prescribed in the appointment of judges to the Supreme Court is that the Chief Justice of India “shall always be consulted”.