Stepwells: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Baoli/ vav

The Times of India, Oct 04 2015

MT Saju

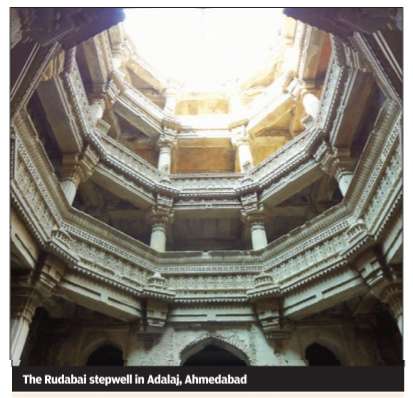

Vavs with wow An American has been documenting the beauty and grandeur of India's stepwells. However, many of them are falling into ruin Thirty years ago, on her first trip to India, Victoria Laut man happened to see the Rudabai stepwell in Adalaj, Ahmedabad. She found it so fascinating that the memory of it stayed with her for years. After several trips to India, four years ago she decided to revisit Rudabai. The trip inspired the Chicagobased journalist to study stepwells across India. Generally an abandoned piece of architecture, few Indian scholars have studied the stepwell in detail. Lautman's passion took her to about 120 stepwells in eight Indian states. The journey of discovery is still on.

“Their beauty and mystery continues to amaze me and I cannot bear the fact that most are crumbling to dust. I never intended to become a stepwell champion,“ she jokes, “but just set out to document as many as I could find.“

According to Lautman, these structures, called baolis in the north and vavs in Gujarat, are unique to India. She has documented all kinds, from the elaborate and well-preserved to the simple and decrepit. “For me, a `spectacular' one might be the simplest, most anonymous, or even the most dilapidated,“ she says.

She rates Rani ki Vav in Patan, Gujarat -a new Unesco World Heritage site -as the best stepwell. “It is the most elaborate, showy , and awe-inspiring one ever built,“ says Lautman.

The journalist says that stepwells first appeared in India between the 2nd and 4th century AD.“It's incredibly hard to find actual dates or often anything at all on so many of the wells. I've seen the date of the earliest wells ranging from 2nd and 7th centuries AD, that's a huge spread,“ says Lautman. “But they were perhaps the most important civic monuments of their day since everyone, everywhere, of all faiths, ages and social levels required water. They provided shade, were important temples, and functioned as community centres and layovers on trade routes.“

Lautman had some tough experiences during her fieldwork. “I was terrified when exploring most of the stepwells, sliding on my bum through filth, warding off bats, bees, snakes and the occasional mongoose, tripping on treacherous stairs,“ she recalls.

Contrary to what many think, stepwells were not necessarily erected at places that faced water shortage. “True, stepwells proliferated in Gujarat, Rajasthan and Haryana, where it gets insanely hot and dry , but everyone needed guaranteed, year-round water supply . Stepwells might not have been nearly as deep in Madhya Pradesh, but they could serve the same function as those in Gujarat,“ she says.

No one has ever come up with at least a rough estimation of how many stepwells existed in India.Even Lautman is clueless. Her research shows that there were reportedly several thousand when the British showed up. “But hundreds were destroyed during the Raj, and once plumbing and village taps arrived, who would bother negotiating perhaps 100 steps to get daily water?“ she says. Even today , she reckons, there could be hundreds. “If you ask around, sooner or later someone will take you to one,“ she says.

Stepwells were pure feats of engineering and architecture. They were sophisticated and efficient in design, but also beautiful. “The creativity in each design should be appreciated along with the sheer variety: they can be round, square, L-shaped, octagonal. There can be one, two, three or four entrances.Like snowflakes, each stepwell is unique and perfect. There's no such thing as a bad stepwell,“ she says.

Lautman has a collection of thousands of photos of baolis and she is keen to compile them into a book. “I'd also love to develop a map so that others can find these baolis,“ she says.

Lautman is disappointed by the lack of tourist information about these structures. “I've had to lead guides to stepwells in their own cities, and no tourist has any idea what or where these structures are, even when they're a stone's throw from the Red Fort, Qutub Minar, Fatehpur Sikri or Taj Mahal. Why aren't these in more guidebooks, itineraries or government websites?“ she asks.And she doesn't understand public apathy to baolis either. “I adore your culture, but it's still your culture, not mine. So why am I the one sliding downstairs?“