Scheduled Castes: status, issues (post-1947)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Scheduled castes

Contents |

Christians, SC certificates for

Church-going dalit cannot be denied SC certificates: HC

A Subramani,TNN | Dec 27, 2013

CHENNAI: There is no rationale in denying scheduled caste (SC) certificate and other benefits to a church-going dalit, the Madras high court has said.

A division bench comprising Justice N Paul Vasanthakumar and Justice T S Sivagnanam, passing orders on a person whose application for SC certificate was rejected by a sub-collector in Puducherry, said going to church could seldom be considered a valid reason to reject the application.

"For deciding the community status, the factors that are to be verified are whether the person is suffering from any kind of social and economic disability and whether the scheduled caste Hindus in the locality are treating the person as one among themselves," they said.

Noting that the sub-collector got carried away by the VAO's report and rejected M Jayaraj alias Ramajayam's claim, the judges said: "Rejection of community/social status community certificate to deserving person will deny his valuable rights guaranteed under the Constitution and attaches civil consequences."

The report merely stated that the Jayaraj was often visiting the church in Othiyampattu village.

The judges said the sub-collector was bound to conduct a proper inquiry and could take a decision only after affording opportunity of hearing to the applicant. Pointing out that such a procedure had not been followed in the present case, they set aside the impugned order dated June 21, 2011. The court also restored the application of Jayaraj and asked the officials to consider the matter afresh and pass fresh orders within four weeks.

Education

Remarkable progress, high dropout rate

The Times of India, January 24, 2016

Subodh Varma

Enrol and dropout, education is a one-way street for Dalits

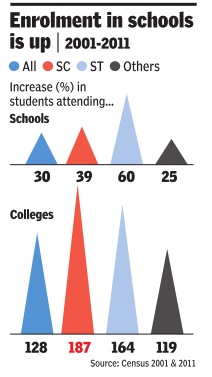

The surge in education among India's most deprived communities, the dalits and adivasis, is re markable: between 2001 and 2011, the share of dalits attending college zoomed up by a staggering 187% and adivasis, by 164%. The comparable increase for all other castes put together is 119%.

So, a large number of dalits and adivasis entered colleges and universities, many of whom would have been first-generation entrants like Rohith. This is all the more remarkable considering the difficult conditions they live in 21% dalit families live in houses with thatch or bamboo roofs compared to 15% overall, 78% stay in one or two roomed houses compared to 69% overall, 35% have a drinking water source within their home compared to 47% overall, 41% do not have electricity compared to 33% overall, and 66% do not have toilets compared to 53% overall.

While school-level enrollment for all castes and communities is roughly the same, there are many more dropouts among dalits and adivasis. Among dalits, the share of school students drops from 81% in the 6-14 years age group to 60% in the 15-19 group. It plummets further to just 11% in the 20-24 age group in higher education. This fall is noticeable across communities and castes but it is the sharpest among dalits and adivasis.

According to an NSSO survey, nearly two-thirds of male dropouts from school and college said that they were needed to supplement the household income while nearly half the female dropouts said that they were needed for domestic chores. The same survey also showed that attendance rates in educational institutions were about 50% in the poorest 10% families but rose to nearly 70% in the richest 10 per cent. Poverty is thus the biggest barrier to pursuing education, and poverty levels are highest among dalits and adivasis. Besides this, these groups also face social discrimination and sometimes, abuse. At a public hearing organized by the People's Trust and CRY in Salem, Tamil Nadu, a young dalit girl, who dropped out of school, said students like her were often taunted and abused by teachers as well as students. She had started working in brick kilns or fields. Shockingly, the same atmosphere prevails in centres of higher education as incidents from various universities and the IITs show.

So, on an average, very few --about one in 10 -students at the higher levels of education are from dalit or adivasi communities. This heightens the sense of isolation among disadvantaged students. And then you have the discrimination, the high costs, the pressure to perfor m, and perhaps -as in the case of Rohith's alma mater -even official hounding.

Offensive names of localities/ villages

Sandeep Rai, Village names are reason for shame, Feb 22, 2017: The Times of India

Calling a Dalit by his caste name is an offence under the SCST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. But Bundelkhand's rigid caste-based society continues to humiliate the Scheduled Castes. Here's how.

Several localities and villages spread over the region are named after the castes of people who live there. There's been a long-standing demand by Dalits to change the names of these localities. But nothing has happened, although candidates of political parties have in the past promised to implement the demand.

Barely 20km from Jhansi is Bajna village, where a large number of Dalits live in a locality called Chamarya. This term is generally associated with Dalit communities such as Jatav and Jatia. They are collectively known as `Chamaar', a prohibited term.

“Every election, we ask candidates to get the names of these villages changed, but we get empty promises.It's embarrassing when you are asked your village name.It immediately reveals our caste identity and the attitude of people around us changes drastically in this caste-driven society of Bundelkhand,“ says Budhh Prakash of Chamroa.

Deep Shikha, Chamarsena's pradhan, said, “We submitted an application to change the name of this village from Chamarsena to Amarsena but I doubt if it's been changed because no one takes us seriously in government offices.“

Owing to extreme subjugation of Dalits in the region, name change of a village or locality often becomes a matter of secondary importance.“A majority of people in these villages are illiterate and downtrodden. Politicians and their strongmen force these people to vote for specific candidates. So, the question of demanding their rights does not even arise,“ said Ganpat Kumar, a school teacher in Chamarya.