River Yamuna: Life on its banks

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Divers and lifesavers

The Times of India, Oct 26 2015

Ambika Pandit

LIVING OFF A DEAD RIVER - Diving for survival, not glory

At the Yamuna ghats are a bunch of people whose job is to scan the depths of the river to keep life and hopes afloat Just 15 years old, Sagar Kashyap has already earned a formidable reputa tion as a lifesaver. Having rescued at least nine children from the Yamuna's waters so far, the teenager thinks swimming is his calling. He wouldn't be far wrong, for his family , four generations in all, has been living by and off the Yamuna. Sagar is a “gotakhor“, a diver who plunges into the chemicalflaked water to rescue floundering people, even to retrieve bodies of suicide victims for families that are seeking a closure. Life by the riverside isn't much of a future to aspire to, but Sagar relishes the responsibility that comes with being asked to assist civic officials in ensuring people don't drown in the river, especially during the immersion of idols. Sagar has boosted his native water skills with a professional swimming career plan at the Talkatora swimming complex, but his less trained compatriots make up with a dose of derring-do. They know the health hazards of jumping into the dirty water, but for a livelihood anything works. Not that it brings them much by way of income; it could be Rs 300 or so, or a bit more on a lucky days.

Sagar has inherited his skills from his father, Bhola Kashyap, 45, who you can run into at the Yamuna Ghat near Kalindi Kunj.He pulls out laminated certificates there is one signed by a district official, another by the Station House Officer of the area police station and a file crammed with newspaper clippings that recall his exploits. His citations say he has rescued 50 people so far.

“I jumped into the water to save a drowning youth and brought him out, but he died in front of my eyes,“ says Bhola of his first unnerving experience as a diver. He recov ered from the trauma over time and then rallied 8 to 10 youngster from the slums of Madanpur Khadar village near the Okhla barrage to become divers.None in his team has professional training, most having learnt diving as a personal survival skill.

The river does not generate much income for him, Bhola, and others of his ilk. So they have to supplement their funds with other activities like RI selling fish when the river isn't as dry as it normally is or running a small general store. Like him, others too face daunting odds.Vikas Paswan, 28, is a case in point.

His father Naresh Paswan moved to Delhi from Kolkata to make a living off the Ya muna as a fisherman and boat man. But a decade later, the elderly man says such a life is not sustain able. Vikas, however, gamely tries to carry on his family's tryst with the river. As a diver, he jumps for any thing from saving lives to fishing out stuff that can be sold in the scrap market.

Bhola worries about his son's pros pects, having realized that there is no future on the banks of the Yamuna.

Sagar is now sensitive to the problems that afflict the river and is wary of the harm ful effects of pollutants on human health. He stresses that he will still ump into the water at any time to save a life, but his sights are set higher. “I want to be national-level swimmer and win laurels for he country,“ the teenager says. One can only hope that the dying Yamuna proves a stepping stone for the young hero.

Fishing in the Yamuna

The Times of India, Oct 25 2015

Jayashree Nandi

Living off a dead river - Catching fish here is a guessing game

Fishermen From Bengal & Bihar Rue Vanishing Of Indian Carps And Their Dwindling Incomes Once the life force of a historic city, the Yamuna is today a lifeless river that meanders for 22 km across Delhi. Politicians have promised to revive the river, to make its water navigable and potable once more. Hundreds of crores have been spent under the Yamuna Action Plan. But every rejuvenation plan has remained just that a plan. The ministry of environment and forests' own annual report for 2014-15 admits that dissolved oxygen (DO), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and coliform levels -parameters that indicate how polluted the water is -remain critically beyond permissible levels downstream of Wazirabad, with the stretches along Okhla and Nizamuddin Bridge being highly toxic. Yet the dying river gamely tries to sustain some communities. Certain people, including the fishermen, dhobis and boatmen, live desperately off whatever little can be squeezed out of the Yamuna. Cynically, there is also a generation that cashes in on the river's ill health. There are those, for instance, whose livelihood depends on collecting and selling the waste that floats on the river. Then there are those who make a macabre living by retrieving valuables from the bodies of people committing suicide, a large number now. In a new series, TOI documents this intense relationship between man and river which shows that in death there can be life too Every time Mangal Sahni flings his fishing net into the torpid waters of the Yamuna winding past Palla village near Wazirabad, there's a prayer on his lips. He hopes that when he draws the net in, he will find a singhara (catfish) in it. He realises that it is more likely his net will snag China machhli or Kamalkar machhli (Chinese carp), but praying for a fish that fetches more in the market is a part of everyday existence on the Yamuna. Life was much easier earlier when the river teemed with popular Indian carps such as the rohu, katla and mrigal and other species that allowed the fishermen to take a decent sum home. But the effluents flowing into the river have taken a toll of the riverine biosphere. Besides the China fish, they also catch chala, puti, mangur and tangra. Depending on the river for a living, however, is now so fraught with risk that Sahni's might be the last genera tion of fishermen here. “The river's condition has deteriorated very fast in the last decade,“ says Ram Shusta Sahni, a 60-year-old who has spent a lifetime catching Indian carps in the river. “We hardly get any rohu or katla or chital (knifefish) that make for good business. In fact, our catches are much smaller now that the river is drying up. Dead fish floating up is very common nowadays.“

For a few generations now, people from Bihar and West Bengal have sustained themselves by fishing in the Yamuna. “The locals are not as poor as us and they own land, so it's mostly the landless from Bihar who fish here,“ says Jaga Sahni, 25. Even as they eke out a living of sorts there, it is a life full of odds and evens. There are days when the fishermen net quintals of China machhli, which sells at Rs 100 a kilo in the wholesale market at Ghazipur. On other days, they do not net even a few kilograms. So their monthly earnings fluctuate wildly between Rs 2,000 and Rs 5,000. The fisher folk from Bihar get an annual fishing permit from either the Haryana or Delhi government and are allocated certain stretches of the river. They spend three to five months from August onward harvesting the Yamuna. In the monsoon months when fishing is not permitted, they return home to try their luck on the Gandak and Bagmati rivers.

Can a dying river sustain this community for long?

Along the 22 km that it flows through the capital, the Yamuna has little water because much of it is withdrawn upstream for drinking and agricultural use. By the time it exits the capital at Okhla, the meagre flow is unbelievably polluted. But Palla's water upstream is also increasingly getting polluted. Says Jaga, “The government knows that a broken drain spews industrial pollutants from Haryana into the river at Barota village and poisons the water, but no action has been taken.“ Indifference surely is killing the river.

Biologists who have carried out studies of the river are distressed by the havoc pollution has caused. Not only has the volume of fish gone down drastically, but wildlife researcher Faiyaz A Khudsar found the diversity of fish itself had been affected. “Major carp species have disappeared, and scavengers like the Asian stinking fish, tilapia and African catfish have increased,“ he says.

No wonder the fishermen are nostalgic about the good old days. The Haldars, Ratan, 61, and Sukumar, 55, came to Delhi in 1965, married in the city and made the Yamuna the pivot of their lives. “The water was deep and very clean then and there was abundant fish.It made sense to move to Delhi for fishing,“ recalls Sukumar.He remembers his friend Liaqat who earned a living ferrying people. “There were many boatmen then, but after 1988 the water became too shallow for boating,“ he adds. Naturally, boatmaking as a business too suffered a silent death.

“Our children will continue to live in this city,“ says Sukumar. And then delivers the requiem for a way of life: “They may never fish for a living though.”

Dhobi ghat/ washermen's colony dwindles

The Times of India, Oct 27 2015

Jayashree Nandi

Dhobi ghat has lost its shine

Laundry stopped coming a long time ago because of the grime and stink of river water. Now old clothes to be recycled given chemical bath before being washed

Just ahead of Loha Pul near Wazira bad, two ageing men work desultorily on the banks of the Yamuna, whose waters run dark and fetid along the dhobi ghat there. Mohammed Sharif, 65, and Mohammed Jamil, 70, heft heavy, damp sheets over their heads and dunk them into a milky concoction of bleach, alum and other compounds before rinsing them in the river. Without this bath in the chemicals, the old men know they will never get the filth out of the cloth because a prolonged soak in the effluent-laced river water leaves a grimy patina on any laundry . The work wasn't as back-breaking some years ago. When younger, the two Mohammeds helped their fathers at the ghat.“The water was clean and the river was just right for the dhobi business,“ sighs Sharif. He philosophically accepts that the washing machine has overwhelmed the dhobi's business across the country, but, the sexagenarian quietly adds, “the Yamuna dhobis have been the worst affected“. He isn't wrong. Though the washermen continue with the work because it is the only way they know how to keep hunger from their doors, their income has shrunk miserably . Households have stopped giving their dirty clothes to the riverbank dhobis because after a wash in the Yamuna, the garments return reeking of sewage and often with darkish stains left by the polluted water. Pushed to the edge and virtually out of business, many Yamuna dhobis now only get the custom of old-cloth sellers.It is common enough in Delhi to see the itinerant peddlers who exchange old clothing for steel utensils. The pieces collected are hawked to shopkeepers, who in turn sell them to factories to use as raw material for various products. The shops first send their piles to the dhobis for a wash at a rupee and a half per item. Suraj Pal, 55, has just received a saffron-coloured dump of such scraps.“This has come from Kolkata and probably has been discarded by sanyasins. There must be a tonne of them here,“ he says, grateful there is some money he can take home today . Downriver, the locality behind the Shas tri Park metro station is luckier because some people still send their soiled clothes to the dhobis, who charge them Rs 5 apiece.

Once a washermen's colony, however, there are a mere five families left in the business now. Mohammed Mustafa, one of them, installed a hand pump to draw cleaner water, but even that is polluted, he claims. “Earlier hospitals used to give us their bed linen, but fear of infection from the effluent has stopped them and our customer base is becoming smaller,“ he says. Social activists wonder why the government has done so little to rehabilitate the community . “The government should provide alternatives until there is adequate safe water for them to return to their profession,“ suggests Manoj Misra, convenor of the Yamuna JiyeAbhiyan, a group working to restore the Yamuna. But the reality is depressing. “Hamarisunwaikabhinahihoti (Our complaints are never considered),“ says Mohammed Shakil, Sharif 's son. “In fact, the government gave us an indirect message to relocate and stop washing in the Yamuna.“ The young man's reference is to the demolition of the dhobi ghats at LohaPul in 2006 as part of the court-appointed Justice Usha Mehra Committee's orders on removal of encroachments within 300 metres of the Yamuna. “Can you believe that as a young man I drank the Yamuna's water?“ says Sharif, rolling his eyes. “I could never have imagined that washing clothes in that water would leave a stink.“ Sharif can no longer afford, as he once did, to send out a cart in the morning, ringing a bell to attract the attention of customers. “Over time, people in the Walled City started sending their laundry to dhobis who had borewells,“ he says, realising perhaps that in time, the Yamuna will cease altogether to be a home for dhobis.

In context of religion

Religious rituals on the banks

The Times of India, Oct 29 2015

Ambika Pandit

Priests at the ghat take a dip in the filthy water and do aarti lest Yamuna's holiness is questioned too much which is bad for business in these difficult times

As the street lights across the Yamuna start throwing shim mering reflections across the darkening water of the river, 72-year-old Ramnath Pehalwan steps out to sweep the steps at Ghat No 23 near Yamuna Bazaar in preparation for the evening aarti. The devotees troop in a little after 7pm, oblivious to the stench in the air and the brightly painted “Yamuna Mission“ antipollution warnings. They pray silently as Pehalwan offers the aarti, his stubbled offers the aarti, his stubbled face brightly illuminated by the wicks.After releasing rose petals into the river, the people thank the ageing panda and return home with a deep sense of peace. The river continues to prove its mystical hold on the faithful. The Yamuna may not be the pristine, holy river it once was, but it still attracts those who have grown up attending rites on its ghats. Along the length of the river lies Nigambodh Ghat, the busiest cremation ground in the capital, and 31 others, right up to the Loha Pul leading to east Delhi. The locals say that worshippers from the “sheher“ (downtown areas) hardly come to the ghats these days, but on festivals like Chhath Puja, the stepped piers teem with crowds.

Prem Chand Sharma, general secretary of the Yamuna Ghat Panda Association, says his family has conducted religious ceremonies and prayers on the river bank for generations. He is recovering from a bout of fever, but the 78-year-old is not prepared to miss the early morning routine of stepping into the filthy water for a dip.He says he knows the dangers this poses to his health, but it is a habit he cannot give up. Like him, many others too take daily ritu alistic dips in the river. However, the younger generation is wary and reluctant to jump in. The old man has seen the Yamuna's better days. As a child, he would leap into the clear water whenever he saw coins on the riverbed. “We used to prepare food using the river water because we believed because we believed the food cooked better that way ,“ recollects Sharma.

The septuagenarian says that like his grandfather and father, he too trained to be a priest, but the going is getting tougher now. “There is work in the morning when people come for rituals and also on auspicious days,“ he says. “Many people come from Haryana too. The Nigambodh Ghat cremation ground being nearby means families come here for the obsequies.“ The trouble, he says, is that this still does not bring in earnings enough to sustain an entire family . Not surprisingly , the younger members of panda families are opting out of the family tradition. Many boys have become swimming trainers at hotels, clubs and even in the CRPF and the Indian Air Force. Eighteen-year-old Ankit, whom we found wrestling by the river, is studying interior designing.

Suresh Sharma, president of the Panda Associations, says the Yamuna's deterioration erodes their faith in the sanctity of the river. His face darkened by disappointment, he talks of plastic trash, mosquitos, the pyres on the riverbank and drains full of effluent flowing into the Yamuna. Why aren't the civic authorities or the government coming up with a workable development plan, he despairs.

Amid this despondency , there is 28-year-old Gopal Jha, who has chosen to follow his elders into the priestly profession. “When people come here, they belittle the Yamuna for being so dirty ,“ he says.“However, when we narrate the river's history and its evolution, they start to empathise.“ The optimistic young man's abiding faith in the river had its best moment a decade ago, when the Panda Association decided to revive the evening aarti as a regular practice to rekindle people's faith in the river's spiritual history . Today , a mix of the old and the young join in the prayers every evening. On the storied ghats, the aarti lamps are a metaphor for the hope that the Yamuna will revert to its sanctified self one day .

Religious offerings consumed by riverbank dwellers

Anindya Chattopadhyay & Jayashree Nandi TNN 2013/06/15

Fishing for food in dangerous waters

Diver boys on the Yamuna bank take a dip in the stinking pool of sewage every day, and often come back with lunch for their families.

Some find a huge sack of dal and the family enjoys it for days. Others sometimes pull out bags of rice, fruits, vegetables, and packs of ghee from the offerings made to the Yamuna and these make their meals on most days. It doesn’t matter if the food was soaked in the most toxic effluents; hunger is overpowering. The Yamuna, though foaming with chemicals, is often a source of nutrition for communities living by it.

Some youths have grown up on the food from the river. “We get oranges, bananas, mangoes, dal, rice, jowar, sugar.I havebeen eating these for years now and it doesn’t bother me,” one of them says.

They also get ‘precious’ items. They pull out coins, metal idols and very rarely even gold objects. A 15-year-old fished out a shiny object and sold it to the scrap-dealer in his colony for Rs 3,000. Some of his neighbours later told him it was made of gold.

Many of them have to submit all items to a contractor who pays them a nominal amount. “We have to give him what we get but we get to keep the food items,” says Paswa who recently found 12kg steel but “the contractor gave me Rs 200 for it”.

Girls are also excited about the day’s lucky pick. “If we get fruits, we are happy. They are usually fresh,” says Tulsi, who goes to an MCD school.

But not everyone can bring back lunch or goodies from the river — these diver boys are usually hired by police to look for corpses or save people from drowning.

Kyari Kashyap, a veteran among the divers, has been in the business for 30 years. “People conduct pujas here and throw a lot of prasad in the river. Why can’t the poor collect them?” Kyari is, however, concerned about pollution levels. He agrees that the food from the river may be unhealthy but that won’t stop people from collecting, he says.

Garbage collectors

The Times of India, October 30 2015

Ambika Pandit

Raft of trash keeps him afloat

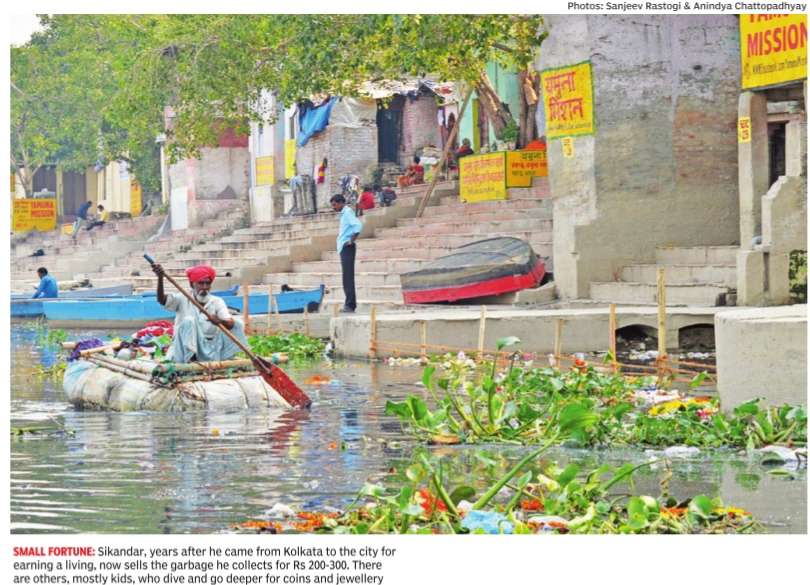

Sikandar & grandson earn a living by collecting whatever they can lay their hands on in the river, in the process cleaning it up of garbage He is all of 10, but he adroitly handles the white float that passes for a boat. It is just some big plastic sacks sewn together, filled with debris and bound into the shape of a square with a creaking scaffolding of bamboos. It is on this improbable raft that Yasser Arafat embarks on a daily adventure along the murky Yamuna to collect the floating trash that he will later sell to waste dealers. When TOI espied him on the stretch between Loha Pul and the ghats bordering Yamuna Bazaar, his raft held a cargo of coconut, scraps of cloth, artificial jewellery items, and plastic and glass bottles. Given the ease with which he yields the oar and controls his makeshift vehicle, it is surprising to know that he is new to the experience. He is in Delhi to see his ailing grandfather, 85-year-old Sikandar, who lives in a shack near the iron bridge. The schoolboy from Kolkata is temporarily taking the old man's place as a ragpicker to ensure the family income isn't affected by the octogenarian's illness.

The youngster's inexperience at the job shows when a man directs a jibe at him for failing to pull in the floating polythene bags. Since he speaks only Ben gali, Yasser only smiles in response. A friendly boatman comes to his rescue with “Abhi naya naya hai.Iska nana toh plastic utha leta hai magar abhi isko nahin pata. (He is new to this work. His grandfather col lects polythene bags to sell, and this boy will soon learn too).“ Yasser has to learn fast because his impoverished family subsists on whatever the Ya m u n a provides each day .In Ben gali, he tells you that the coconut he fishes out from the water fetches Rs 8 each when his father takes the day's collection to a riverine version of a fence. He holds up a tarnished earring and says, “Loha (iron)“. Clearly, he means to hawk it as metallic scrap.

His grandfather is a familiar face on the Yamuna here. Inured to the stench and the filth lining the river bank, Sikandar works his way through the mess of hyacinth and rotting marigold garlands, keeping a sharp eye out for any saleable junk. His daily expedi tions on the polluted river are, of course, propelled by his dire poverty, but within sight of the bright yellow “Mission Yamuna“ anti-pollution posters on the ghats, the old man contributes his mite to the cleaning of the Yamuna in his own inimitable way .The priests also occasionally pay him to remove the muck from the water lap ping the ghat steps.

The day we met Sikandar, he had had a fruitful day. His raft was filled with colourful cloth pieces discarded after various rituals on the ghats. He had even managed to pull in a pumpkin that had probably floated away from a riverside vegetable patch. In the many years he has spent living off the Yamuna, Sikandar has learnt to speak Hindi like a local. When asked why he left Kolkata, he said he came to Delhi to earn a living, never imagining that garbage would give him his daily earnings of between Rs 200 to Rs 300.

Downriver, near Ka lindi Kunj, where the Yamuna exits Delhi on its way to Mathura, there are others who live off the city's sunken de tritus. Religious Indi ans honour the rivers by throwing in small change, and Faizal, a 15-year old school dropout, re gularly plumbs the depths there to pry out coins from the silt. The teenager and his friends are unaware that every time they dive in or accidentally swal low the water, they are exposed to skin infections and worse. But their poor families need the Rs 200 or so they haul out on a good day .

The smaller kids comb the water close to the river bank for similar riches. Sonu, a 10-yearold who lives in the Priyanka camp at Madanpur Khadar nearby, spends two hours after school every day dragging his fingers through the mud. His widowed mother works as a domestic help, and what he finds and sells supplements her meagre earnings.

Today, in his very first attempt, he has found a damaged silver ring with an artificial pearl intact. “It will bring in at least Rs 200,“ he says cheerfully and hurries home. The Ya muna has given him another day of sur vival. His friends look , at his receding figure and go back to their own desperate search es, hoping that the day will be different, that the Yamuna will be more generous as it has been to Sonu.

River in spate holds fortune for many

Neha Lalchandani | TNN2013/06/19

The havoc wreaked by the gushing river upstream of Delhi was evident in its water as it passed through the city. Hundreds, maybe thousands, of water melons, bottle gourds and pumpkins were seen being carried by the Yamuna, a reminder of the acres of agricultural land that have been inundated.

At the Old Railway Bridge, the road was closed for traffic once the Yamuna crossed the danger mark. The road was taken over by pedestrians and groups of boys who perched precariously from the railing with nets to trap the fruits and vegetables as they flowed under the bridge. On the other side of the bridge, youngsters cast massive blocks of magnets into the river and fished out coins.

By afternoon, the bridge was dotted with smashed pieces of red watermelons. Thrilled people carried off their fruits purchased for a pittance from the boys who spent hours netting these. “We have been doing this all morning, and for a price of Rs 5-10, we have pulled out fruits for people. The flow is extremely strong and it is very tiring work. We have been taking turns in holding the net,” said Pappu, a 15-year-old who had spent the better part of the day earning close to Rs 200.

Singharas (water chestnuts)

The Times of India, Oct 28 2015

Anindya Chattopadhyay

Bijnor to Delhi for singharas

Growing water chestnuts at a floating farm on the river has been lucrative for these men who come twice a year to city.

It's not often that you will meet some one these days who will sing praises of the Yamuna. But Mohammed Ria zuddin, 55, surveys his crew bobbing up and down on perilous contraptions fabricated out of rubber tubes on the water, pulling at a floating mess of leaves. His dark, pitted face breaks into a bright smile as he says, “Log Yamuna ko ganda bolte hain par hum to isi ke pas baithe hamare pariwar ka pet chalate hain (People decry the Yamuna for its polluted water, but to me it is the provider of food for my family).“ As he speaks, one of his workers pulls in a net full of burgundy-green fruit. Every kilo of the singhara (water caltrop or water chestnut) harvest will fetch Riazuddin Rs 40 at the wholesale market. For two decades now, Riazuddin has farmed water chestnut in a private wetland fed by the Yamuna. Having come to the capital to try his luck from Bijnor in Uttar Pradesh, he promptly saw an opportunity in replicating the traditional business of most families back home. Today he is the proud owner of the 40-bigha holding at Rainy Well Thoka Number 13 in east Delhi, where with little competition and a good demand for the starchy edible seed, he has been able to experience the benevolence of a famed river. Anyone who sees the men expertly manoeuvring their rubber floats in the sea of stalks and leaves will realise that harvesting water chestnut is an art in itself. Such expertise is hard to find in the capital, and Riazuddin brings in his workforce of around 10 men from Bijnor. “Back home, every household is into the singhara business. My father and grandfather did the same thing,“ says Pappu as he gathers the long stalks of the caltrop plant and plucks the nuts. He comes twice a year with Satpal Singh, Jaipal Singh, Zaheer Hussain, Sher Singh and some others to work at the floating farm near Kishankunj ¬ once at sowing time at the outset of the monsoons and then again between September and November at harvest time. On good days, the men collect up to 800 kg of singhara, which are carted off by vendors and wholesalers from Ghazipur mandi.Each man earns Rs 250 for a day's work. It is quite a windfall for them, because, as Pappu say, “The rest of the year we work as labourers.“ However, the money is hard-earned. For one, they work half submerged in polluted water and there is no way of knowing what hazards lie beneath the muddy, leaf-strewn surface. There have been cases of snake bites, and in Bijnor, even deaths. The Yamuna's alarming deterioration is obviously taking a toll on the business and making the job of these men a health risk.At the time of sowing, Riazuddin uses a special compound, a white powder that coagulates the pollutants, which sink to the bottom, leaving fairly clear water on the top.The water chestnuts are then sown. This year, says Riazuddin, his income will be hurt by a lower than usual yield.Pesticide-laced water from neighbouring fields flowed into his farm during the monsoons and contaminated his crop. Yet, unlike many others who live off the dying river, the greying Riazuddin refuses to think of the Yamuna's demise. “Our survival is dependent on it. It's a source of life for all of us from Bijnor,“ he says, as his eyes stray to the sacks of strangely-shaped fruit waiting to be hauled away .