River Yamuna

(→Religious offerings consumed by riverbank dwellers) |

(→Fishing in the Yamuna) |

||

| Line 280: | Line 280: | ||

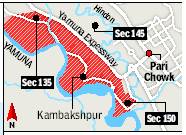

[[File: Yamuna1.jpg|Yamuna river; Graphic courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=LIVING-OFF-A-DEAD-RIVER-Catching-fish-here-25102015006007 ''The Times of India''], Oct 25 2015|frame|500px]] | [[File: Yamuna1.jpg|Yamuna river; Graphic courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=LIVING-OFF-A-DEAD-RIVER-Catching-fish-here-25102015006007 ''The Times of India''], Oct 25 2015|frame|500px]] | ||

| − | |||

[[File: Yamuna3.jpg|Graphic courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=LIVING-OFF-A-DEAD-RIVER-Catching-fish-here-25102015006007 ''The Times of India''], Oct 25 2015|frame|500px]] | [[File: Yamuna3.jpg|Graphic courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=LIVING-OFF-A-DEAD-RIVER-Catching-fish-here-25102015006007 ''The Times of India''], Oct 25 2015|frame|500px]] | ||

Revision as of 15:14, 4 November 2015

This is a collection of newspaper articles selected for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Riverfront planning: 1913-2000

Feb 11 2015

Jayashree Nandi

Riverfront planners caught in time warp

Govt trying to urbanize Yamuna since 1913: Scientists

Delhi had planned for a riverfront for Yamuna as early as 1913 to give the new capital an aesthetic promenade from Wazirabad in the north to Indrapat (Purana Qila and its surroundings) in the south.Hundred years on, the central government continues to idealize urban riverfronts like that of the Sabarmati and has been floating proposals to make Yamuna an urban infrastructure component such as dredging it to make it navigable. Awadhendra Sharan, associate professor at Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, whose research paper on Yamuna was published in Elsevier's journal of City , Culture and Society, traces how various authorities at different times in history tried to develop the river and the riverfront.

Around 1956, the Town Planning Organization suggested development of a riverfront for recreational activities with playgrounds, swimming pools, and fishing and bathing areas. “It drew attention to the possibility of taming the river by building a dam,“ writes Sharan.

Cultivation of melons on the banks in summer and fishing were common in Okhla. Floods were an annual phenomenon but there was ample land for free flow of river during the monsoon months. A new phase of urbanizing the river began after Independence in 1955-56 leading to floods becoming a health issue with w aste water discharge points near the river affecting quality of drinking water. In 1990, DDA too planned several urban projects to integrate the city and river.

Over the past two decades, Yamuna became extremely polluted and ceased to be a peren nial river. This is when the gov ernment started blaming squatters in illegal colonies along Yamuna for the pollution and began pushing “technologi cal solutions“. One of the major changes in approach is marked by the high court nod to the Com monwealth Games Village. Sha ran recollects in his paper how there were discrepancies in var ious technical reports submit ted to the court on the impact of Games Village which led to the court deciding that the area for it was not on the floodplains.

Another high court decision in March 2003 led to removal of the Yamuna Pushta slum clus ter. But various studies and ex perts say this will not help ad dress pollution.Sharan suggests the “precautionary principle“ should have been applied before such irreversible changes--like building Akshardham and the Games Village--were made. “I have tried to argue from all the historical evidence that's availa ble that we should leave the river as it is and not convert it into a re al estate operation. That makes more economic and ecological sense,“ Sharan says.

Yamuna: The state of the river/ Pollution

6,500cr and 19yrs later, Yamuna dirtier than ever/ Clean-Up Plan Flops, SC Review today

By Neha Lalchandani 2013/03/11

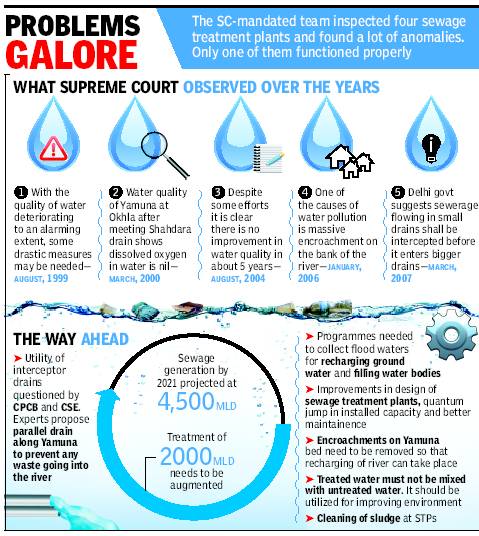

[In 1994?] the Supreme Court first scrutinized pollution in the Yamuna. Innumerable orders later, Yamuna is dirtier than ever with a mind-numbing Rs 6,500 crore spent to clean the river and the latest plan — interceptor sewers — going

When SC reviews Yamuna’s pollution, it could be back to the drawing board. Six years after the Delhi Jal Board proposed interceptor sewers to treat sewage before it flows into major drains, just Rs 51 crore of the Rs 1,963 crore scheme has been spent.

Worse, it is not even clear if the measure that was to improve water quality by 2010 will actually work in light of the rapid growth of unauthorized colonies discharging sewage into the river, an issue flagged even in 2007 by an official committee that approved the interceptor proposal.

The committee had warned that 1,432 unauthorized colonies were the nub of the problem. By 2012, their number had jumped to 1,639. Although these colonies have been promised regularization, drainage and sewers are years away. In 2007, 517 of 567 unauthorized regularized colonies had sewers. The number grew by just six in the next five years. DJB says it is tough to provide sewerage in such densely populated colonies where they have barely any road space for their work.

A report submitted to the court by an inspection team that included amicus curiae Ranjit Kumar as recently as November last year called for sewage connections to all new colonies, whether authorized or not.

It pointed out that Delhi’s 17 sewage treatment plants (STPs) have a capacity of 2,460 MGD against utilization of 1,558 MGD. Delhi’s sewage generation is around 3,800 MGD.

Throwing money in the river

6,500cr spent by Delhi, UP and Haryana to clean Yamuna. This includes central funds. No improvement in water quality in past 8 yrs Only 51cr of 1,963cr sanctioned for interceptor drains spent. Scheme proposed in 2007, was to deliver results by 2010 Number of unauthorized colonies has jumped from 1,432 in 2007 to 1,639 in 2012

Only 55% of Delhi’s population served by sewer system

Delhi’s installed sewage treatment capacity is 2,460 MLD. Sewage generated is 3,800 MLD. But just 63% of installed capacity is being used

City’s biggest drain, Najafgarh, discharges 2,064 MLD. Only 30% is treated.

Worse, treated sewage is again mixed with waste

SC-mandated team inspected 4 sewage treatment plants in November 2012.

All four were deficient

Heavy metals in city’s drinking water

Delhi’s drinking water is contaminated with tonnes of industrial waste. Industries located upstream of the Yamuna have been found to be discharging untreated waste into the river, leading to the presence of heavy metals in water that is picked up at Wazirabad to meet the city’s drinking water needs.

Manoj Misra of the Yamuna Jiye Abhiyan had water from the Dhanura Escape — a channel that empties into the Yamuna — tested at a laboratory in Gwalior and found that the levels of chromium, lead and iron were higher than permissible. “While chromium was 0.13 mg/l against 0.05 mg/l, lead was 0.035 mg/l against 0.01mg/l and iron was 3.51mg/l against a permissible 0.1 mg/l. The presence of heavy metals is even more problematic since the treatment plants in Delhi are not equipped to detect or treat them,” said Misra.

Pollution from industries in Haryana, especially those located in and around Panipat and Sonepat, has caused treatment plants to stop functioning on several occasions after ammonia level went so high that it could not be treated. Untreated industrial effluent from Yamuna Nagar, Misra said, is released into the Dhanura Escape from where it meets the river upstream of Kunjpura in the Karnal district.

“Similarly, toxic waste from Panipat falls into the Yamuna near the village of Simla Gujran in Panipat district. Samples from the Dhanura Escape show presence of heavy metals, known health hazards and a clear indication of industrial pollution. This water is picked up at Wazirabad for treatment at Chandrawal and Wazirabad treatment plants,” he said.

Other than heavy metals, other pollutants, too, were much higher than BIS norms for drinking water. Total coliform was 1,200 against the permissible limit of 10, total dissolved solids were 3,324 against the permissible limit of 500, biochemical oxygen demand was 240 mg/l against a limit of 30 mg/l, and chemical oxygen demand was 768 mg/l against a limit of 250 mg/l, Misra added.

Central Pollution Control Board officials said they had made it compulsory for all industries to have effluent treatment plants. “Most industries have installed ETPs but either the treatment is not up to mark or not all effluent is reaching the ETPs. We have set up a real time water pollution monitoring station at Wazirabad where we monitor 10 parameters... heavy metals are not monitored as they cannot be treated in the plants,” said an official.

The wish list

Haryana government release more water from Hathnikund Barrage for Uttar Pradesh

Alternate arrangement be made for disposal of untreated sewage in Delhi, which is at present dumped into the river at 22 places

The holy river be given due respect

The water has not improved despite generous funds

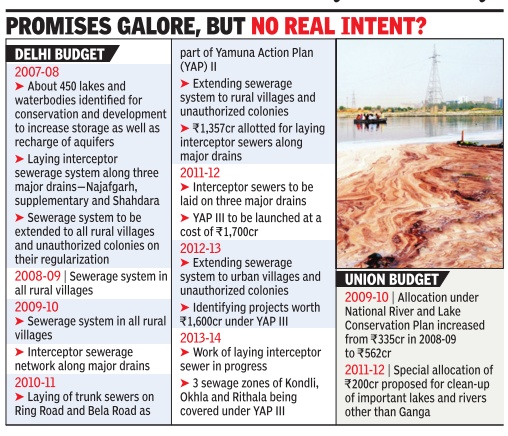

WATER QUALITY WORSE - Funds flow, Yamuna stays filthy

Jayashree.Nandi@timesgroup.com New Delhi

The Times of India Jul 15 2014

Every year the state and union budgets raise hopes that the Yamuna may after all soon get a new lease of life. In fact, the Delhi government's budget has been making the exact same promise for seven years (2008-14). Providing sewerage in urban villages and unauthorized colonies and laying interceptor sewers along major drains is its solution for Yamuna's pollution crisis. It has allotted over Rs 3,500 crore for these projects--mostly under the Yamuna Action Plans--to complete the work and ensure “discharge of pollutants comes down considerably“.

But 2014 Yamuna water sample investigations by Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) show levels have not improved; they are worse at some sites. Delhi Pollution Control Committee (DPCC) officials also confirmed to TOI that water quality parameters including biological oxygen demand (BOD) and total coliform levels have only deteriorated or are the same in almost all monitoring sites.

Interestingly , Delhi Jal Board (DJB) claims that 68% of the work of laying the interceptor sewer--large sewer lines that control the flow of sewage to a treatment plant--is already done. The project is divided into packages, out of which two will be completed by the end of 2014 and the rest by 2015. It also claims that of 2,574 urban and rural villages, unauthorized colonies and other un-sewered colonies, sewerage was provided in 842.

But no one seems to be sure why water quality hasn't started improving. One of the reasons, say officials, is that these projects will work only when sewage treatment plants func tion to their full capacity. As of now, most STPs are functioning at 50% capacity .

The funds allocated by the union government are also difficult to track. “The union government for instance allocated Rs 562 crore for rivers in 2009 and Rs 200 crore in 2011 for lakes and rivers and Rs 100 crore for “ghat development and beautification“ for seven river side cities including Delhi this time.

Pollution in Yamuna

Increasing pollution in Yamuna

After 21 years of SC monitoring, Yamuna still stinks like a sewer

The Times of India, Jan 09 2015

Amit Anand Choudhary & Dhananjay Mahapatra

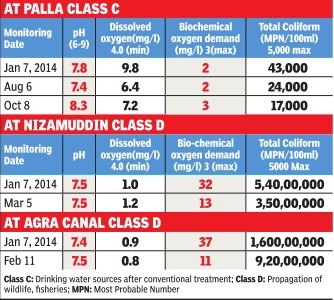

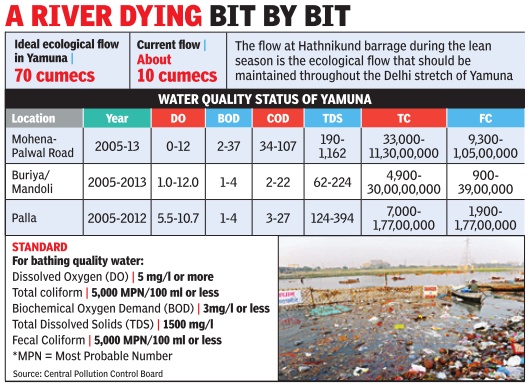

4 Lakh To 16 Crore Coliform In River Against Norm Of 5,000, CPCB Tells SC

Central Pollution Control Board told the Supreme Court why the Yamuna in its 22-km course through Delhi mostly stinks like a sewer drain as against the norm of 5,000 MPN coliform per 100 ml of water, Yamuna water in Delhi had between 4 lakh to 16 crore coliform per 100 ml. The norm of 5,000 MPN100 ml of water is the quality prescribed for `C' category of water, which is fit for drinking after treatment.But, on January 7, 2014, the total coliform in Yamuna water at Nizamuddin was 54000000 (5.4 crore) and at Kalindi Kunj it was 160000000 (16 crore). But, at Palla the river water is relatively clean. On January 7 last year the total coliform detected at Palla was 43,000.

After 21 years of intense monitoring of government efforts by the Supreme Court to clean the Yamuna, the CPCB, through advocate Vijay Panjwani, submitted to the court a detailed report on the state of pollution of river water at Pal la, Nizamuddin, Kalindi Kunj, Okhla and Madanpur Khadar in the 22-km stretch it flows through Delhi.

Despite the SC monitoring, Delhi appeared to be the biggest culprit in polluting the river. The water quality of Yamuna at Palla when it enters Delhi met the standard of “A“ grade water, which is fit for drinking without conventional treatment but after disinfection, in respect of pH level, dissolved oxygen, bio-chemical oxygen demand as well as coliform on most days except on five of the 12 testing days between November 19, 2013 and October 8, 2014.

But at the rest of the places through the city , the water did not even qualify to the standard of “C“ grade water and was declared unfit for even bathing. The CPCB also submitted the quality of water in 22 drains that joins Yamuna during its course through Delhi.

A year ago in December 2013, the Supreme Court had sought expert help from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) after being told by CPCB that despite Rs 5,000 crore spent for reducing pollution, the river was staring at a catastrophe as over 2,400 million litres of untreated sewage flows into it every day.

Since 1994, when the apex court took up monitoring of steps to reduce pollution in Yamuna, Uttar Pradesh has spent Rs 2,052 crore, Delhi government and its civic bodies Rs 2,387 crore and Haryana Rs 549 crore to clean the river, taking the total to Rs 4,988 crore.

A joint report by CPCB and DJB had informed the court a year ago that the situation would get worse as “waste water generation due to growth of urban population will be substantial and may be in the range of about 5,000 to 6,000 MLD respectively for the corresponding years 2021 and 2031“.

Rain not washing away toxins

Rain not washing away Yamuna toxins Jayashree Nandi The Times of India Dec 01 2014

New Delhi

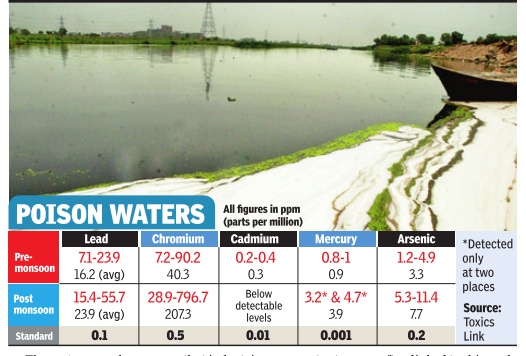

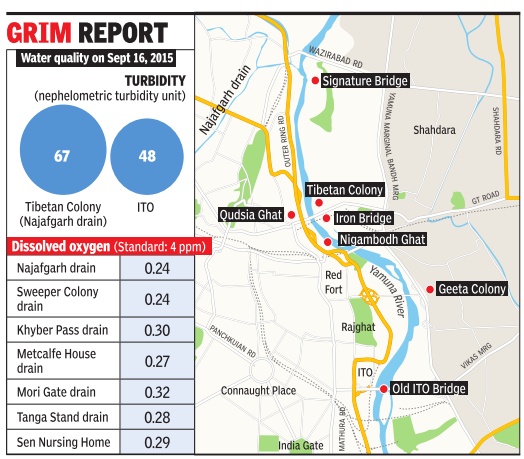

Yamuna water is toxic, to say the least. But what is worse is that there seems to be a continuous discharge of industrial effluents into the Delhi stretches of Yamuna so that there is no improvement in postmonsoon months either when pollution is supposed to be far more diluted.

A recently concluded study by Toxics Link, an environmental NGO, found heavy metals like lead, chromium, arsenic and mercury to be several times the safe standard and, in some cases, even several hundred times the bathing water quality standard set by Central Pollution Control Board in preand post-monsoon months.

A team of researchers collected water samples from seven locations starting with Jagatpur village where the water appears to be marginally cleaner. The researchers travelled by boat to be able to collect water in bottles and buckets from near Najafgarh drain, Wazirabad, Majnu Ka Tila, near Vidhan Sabha drain, ISBT and Yamuna Bazar. The water samples were analysed for the most toxic heavy metals. Chromium levels were the highest with a maximum concentration of about 796.99 parts per million when the standard is 0.5ppm. The maximum level for lead was 55.7ppm when the standard is 0.1ppm.

“We couldn't find a uniform trend in preand postmonsoon levels which show that industries are constantly discharging these heavy metals leading to high toxicity levels throughout. We are also assessing whether the high chromium levels are due to tanneries discharging untreated effluents. But it's clear that a lot of industrial waste is polluting Yamuna,“ said Prashant Rajankar, programme coordinator, Toxics Link. High chromium levels are often linked to skin rashes, ulcers, weakening of the immune system, kidney and liver damage and many other health impacts.

The study was also used as an introduction for the recently concluded India Rivers Week where about 125 academics, scientists, activists from all states thrashed out the definition of a “healthy river“ and what is ailing Indian rivers. The reason for organizing such a conference is also the current government's agenda of interlinking rivers.

The 125 experts will work in four groups to arrive at a consensus on certain crucial issues related to rivers and controversial or `environmentally unsound' projects like interlinking or rivers, massive hydropower projects, dams and others. At the end of four days, experts will prepare an India rivers charter articulating the vision for saving rivers.

At IRW, experts also drew attention to a recent appraisal by Yamuna Jiye Abhiyan that has found there is no river in any of the top 50 cities (based on population) in India that is not sick or dying with river Yamuna in DelhiMathura-Agra and Ganga in Kanpur-Varanasi-Patna leading the list.

Pollution is irreversible

The Times of India, Feb 08 2015

Yamuna pollution can't be reversed: Water commission

Arvind Chauhan

The Yamuna, by the time it flows through Agra, has nearly 50 times more biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) than the permissible limit. The Central Water Commission (CWC) has declared that the river water at Agra is safe neither for irrigation nor for domestic use.Water in the river, now polluted beyond repair, an official said, is also contaminating ground water.

BOD is the amount of dissolved oxygen needed by aerobic biological organisms to break down orga nic material, in a given time and at a certain temperature. Once BOD increases beyond a certain limit, it becomes a pollutant, leading to the growth of harmful bacteria.

BOD forms when the equilibrium of chemical compounds and solid waste is disturbed in a water body .

A CWC official said, “This contamination level is irreversible. Water is unusable, both for irrigation and drinking. In fact, polluted water from the Yamuna is also partially responsible for the contamination of ground water in Agra.

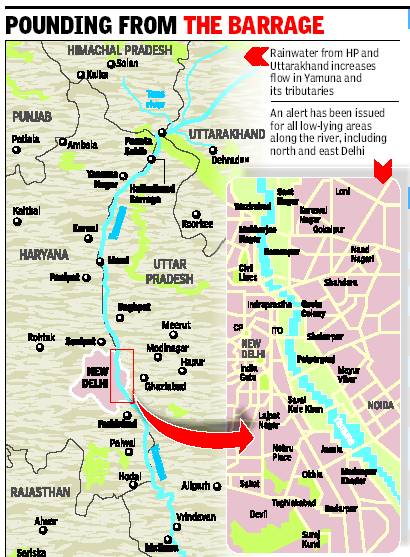

Floods in Yamuna

The Yamuna: The highest flood levels recorded

The Yamuna, which has been reduced to being just a drain, transforms during the rains into a raging, menacing river

1978 | 5 Sept 207.49m

The Yamuna touched 207.49m on September 5 after 7 lakh cusec water was released upstream. Large parts of west, north and east Delhi, including Shalimar Bagh, Model Town and Mukherjee Nagar, were under 4-5 feet of water. It remains Delhi’s worst flood to date

1988 | 21 Sept 206.92 m

Continuous torrential rain in the hills from September 21 raised the Yamuna’s level to 206.92m at the Old Railway Bridge. Many areas in east and north Delhi, including Mukherjee Nagar, Geeta Colony, Yamuna Bazaar and Red Fort were affected

1995 | Sept 206.93 m

In Sept, river touched 206.93m. While release from Tajewala was massive, Delhi didn't let out water from Okhla barrage fast enough. Around 15,000 families lived in temporary shelters on main road for two months

2010 | Sept 207.11 m

Towards the end of September, the Yamuna rose to 207.11m and stayed at that level for eight hours. Areas like Kashmere Gate, Batla House, parts of Ring Road, Jaitpur and Majnu Ka Tila were flooded. Back flow from sewers submerged hundreds of houses in low areas

Do floods help the Yamuna?

2013/06/22

Swell in Yamuna kills the stink

If you thought the Delhi stretch of Yamuna had long become a sewage pool, visit the river now. Flooded to the brim, it is reminiscent of what Yamuna may have originally looked like. The flood may have played havoc by displacing communities but it has also managed to dilute the polluted water and enliven a dead river.

Towards Okhla (downstream) the river water usually has a biochemical oxygen demand of 40 to 50 mg/l but since June 15, the BOD measured less than10 mg/l according to Central Pollution Control Board.

BOD is an important determinant to show how polluted the river water is. It is a measure of the quantity of oxygen used by microorganisms in the oxidation of organic matter. The acceptable limit of BOD is 3 mg/l.

“The pollutants have been washed away but the water is very turbid because of the debris that has come with the floodwater and runoff from agricultural fields. Even after the water level recedes, there will still be surplus water and we expect that pollution levels will be low for about two months,” said a senior officer from CPCB.

The flooding will also have an impact on the groundwater say scientists. Saumitra Mukherjee, professor of geology and remote sensing, School of Environmental Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, says that there are lots of negative effects of flooding but one of the positive impact is the improvement in soil quality. “The flood brings with it fine silt, clay and sand. These and the sediment formed from them are usually fertile and can be beneficial for agricultural purposes. The floodwater also helps recharge underground aquifers,” he says.

However, he warns that the floodwater loaded with fecal matter can contaminate both the surface water and groundwater. “There has to be intensive monitoring of the water quality to check if it can cause contamination. When the floodwater starts receding there is a high chance of an epidemic and spread of bacterial infection among communities living by the river,” he adds.

The flooding also impacts aquatic life. The dead river may now have enough water to create the environmental conditions for spawning of certain species of fish.

“Floods are very important for Yamuna in Delhi. Earlier we had a lot of wetlands but development has eaten in to those. Usually during floods when the floodwater recedes, these pools or wetlands are recharged. Even our floodplains have been encroached upon. We need forests and grasslands by the river to retain and use the floodwater. We need a river front forest ecosystem,” adds Faiyaz A Khudsar, scientist at Yamuna Biodiversity Park

Floods rejuvenate river

Soil and water quality in Yamuna likely to remain slightly better for a couple of months from now Contaminated floodwater can also pollute groundwater. There are high chances of an epidemic as water recedes

Floodwater loaded with fine silt, clay and sand is likely to make the Yamuna soil fertile and will be benefi cial for agriculture

Floodwater will help recharge underground aquifers

It will rejuvenate wetlands near Yamuna

Flooding can induce breeding or spawning in some fish species in Yamuna

Flooding has already diluted polluted water near Okhla

Flooding can be alarming for some species like snakes and insects, which have started coming out of the burrows

River corridor vegetation and agriculture in floodplains likely to improve after fl oodwater recedes

Life on Yamuna’s banks

River in spate holds fortune for many

Neha Lalchandani | TNN2013/06/19

The havoc wreaked by the gushing river upstream of Delhi was evident in its water as it passed through the city. Hundreds, maybe thousands, of water melons, bottle gourds and pumpkins were seen being carried by the Yamuna, a reminder of the acres of agricultural land that have been inundated.

At the Old Railway Bridge, the road was closed for traffic once the Yamuna crossed the danger mark. The road was taken over by pedestrians and groups of boys who perched precariously from the railing with nets to trap the fruits and vegetables as they flowed under the bridge. On the other side of the bridge, youngsters cast massive blocks of magnets into the river and fished out coins.

By afternoon, the bridge was dotted with smashed pieces of red watermelons. Thrilled people carried off their fruits purchased for a pittance from the boys who spent hours netting these. “We have been doing this all morning, and for a price of Rs 5-10, we have pulled out fruits for people. The flow is extremely strong and it is very tiring work. We have been taking turns in holding the net,” said Pappu, a 15-year-old who had spent the better part of the day earning close to Rs 200.

Divers and lifesavers

The Times of India, Oct 26 2015

Ambika Pandit

LIVING OFF A DEAD RIVER - Diving for survival, not glory

At the Yamuna ghats are a bunch of people whose job is to scan the depths of the river to keep life and hopes afloat Just 15 years old, Sagar Kashyap has already earned a formidable reputa tion as a lifesaver. Having rescued at least nine children from the Yamuna's waters so far, the teenager thinks swimming is his calling. He wouldn't be far wrong, for his family , four generations in all, has been living by and off the Yamuna. Sagar is a “gotakhor“, a diver who plunges into the chemicalflaked water to rescue floundering people, even to retrieve bodies of suicide victims for families that are seeking a closure. Life by the riverside isn't much of a future to aspire to, but Sagar relishes the responsibility that comes with being asked to assist civic officials in ensuring people don't drown in the river, especially during the immersion of idols. Sagar has boosted his native water skills with a professional swimming career plan at the Talkatora swimming complex, but his less trained compatriots make up with a dose of derring-do. They know the health hazards of jumping into the dirty water, but for a livelihood anything works. Not that it brings them much by way of income; it could be Rs 300 or so, or a bit more on a lucky days.

Sagar has inherited his skills from his father, Bhola Kashyap, 45, who you can run into at the Yamuna Ghat near Kalindi Kunj.He pulls out laminated certificates there is one signed by a district official, another by the Station House Officer of the area police station and a file crammed with newspaper clippings that recall his exploits. His citations say he has rescued 50 people so far.

“I jumped into the water to save a drowning youth and brought him out, but he died in front of my eyes,“ says Bhola of his first unnerving experience as a diver. He recov ered from the trauma over time and then rallied 8 to 10 youngster from the slums of Madanpur Khadar village near the Okhla barrage to become divers.None in his team has professional training, most having learnt diving as a personal survival skill.

The river does not generate much income for him, Bhola, and others of his ilk. So they have to supplement their funds with other activities like RI selling fish when the river isn't as dry as it normally is or running a small general store. Like him, others too face daunting odds.Vikas Paswan, 28, is a case in point.

His father Naresh Paswan moved to Delhi from Kolkata to make a living off the Ya muna as a fisherman and boat man. But a decade later, the elderly man says such a life is not sustain able. Vikas, however, gamely tries to carry on his family's tryst with the river. As a diver, he jumps for any thing from saving lives to fishing out stuff that can be sold in the scrap market.

Bhola worries about his son's pros pects, having realized that there is no future on the banks of the Yamuna.

Sagar is now sensitive to the problems that afflict the river and is wary of the harm ful effects of pollutants on human health. He stresses that he will still ump into the water at any time to save a life, but his sights are set higher. “I want to be national-level swimmer and win laurels for he country,“ the teenager says. One can only hope that the dying Yamuna proves a stepping stone for the young hero.

Fishing in the Yamuna

The Times of India, Oct 25 2015

Jayashree Nandi

Living off a dead river - Catching fish here is a guessing game

Fishermen From Bengal & Bihar Rue Vanishing Of Indian Carps And Their Dwindling Incomes Once the life force of a historic city, the Yamuna is today a lifeless river that meanders for 22 km across Delhi. Politicians have promised to revive the river, to make its water navigable and potable once more. Hundreds of crores have been spent under the Yamuna Action Plan. But every rejuvenation plan has remained just that a plan. The ministry of environment and forests' own annual report for 2014-15 admits that dissolved oxygen (DO), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and coliform levels -parameters that indicate how polluted the water is -remain critically beyond permissible levels downstream of Wazirabad, with the stretches along Okhla and Nizamuddin Bridge being highly toxic. Yet the dying river gamely tries to sustain some communities. Certain people, including the fishermen, dhobis and boatmen, live desperately off whatever little can be squeezed out of the Yamuna. Cynically, there is also a generation that cashes in on the river's ill health. There are those, for instance, whose livelihood depends on collecting and selling the waste that floats on the river. Then there are those who make a macabre living by retrieving valuables from the bodies of people committing suicide, a large number now. In a new series, TOI documents this intense relationship between man and river which shows that in death there can be life too Every time Mangal Sahni flings his fishing net into the torpid waters of the Yamuna winding past Palla village near Wazirabad, there's a prayer on his lips. He hopes that when he draws the net in, he will find a singhara (catfish) in it. He realises that it is more likely his net will snag China machhli or Kamalkar machhli (Chinese carp), but praying for a fish that fetches more in the market is a part of everyday existence on the Yamuna. Life was much easier earlier when the river teemed with popular Indian carps such as the rohu, katla and mrigal and other species that allowed the fishermen to take a decent sum home. But the effluents flowing into the river have taken a toll of the riverine biosphere. Besides the China fish, they also catch chala, puti, mangur and tangra. Depending on the river for a living, however, is now so fraught with risk that Sahni's might be the last genera tion of fishermen here. “The river's condition has deteriorated very fast in the last decade,“ says Ram Shusta Sahni, a 60-year-old who has spent a lifetime catching Indian carps in the river. “We hardly get any rohu or katla or chital (knifefish) that make for good business. In fact, our catches are much smaller now that the river is drying up. Dead fish floating up is very common nowadays.“

For a few generations now, people from Bihar and West Bengal have sustained themselves by fishing in the Yamuna. “The locals are not as poor as us and they own land, so it's mostly the landless from Bihar who fish here,“ says Jaga Sahni, 25. Even as they eke out a living of sorts there, it is a life full of odds and evens. There are days when the fishermen net quintals of China machhli, which sells at Rs 100 a kilo in the wholesale market at Ghazipur. On other days, they do not net even a few kilograms. So their monthly earnings fluctuate wildly between Rs 2,000 and Rs 5,000. The fisher folk from Bihar get an annual fishing permit from either the Haryana or Delhi government and are allocated certain stretches of the river. They spend three to five months from August onward harvesting the Yamuna. In the monsoon months when fishing is not permitted, they return home to try their luck on the Gandak and Bagmati rivers.

Can a dying river sustain this community for long?

Along the 22 km that it flows through the capital, the Yamuna has little water because much of it is withdrawn upstream for drinking and agricultural use. By the time it exits the capital at Okhla, the meagre flow is unbelievably polluted. But Palla's water upstream is also increasingly getting polluted. Says Jaga, “The government knows that a broken drain spews industrial pollutants from Haryana into the river at Barota village and poisons the water, but no action has been taken.“ Indifference surely is killing the river.

Biologists who have carried out studies of the river are distressed by the havoc pollution has caused. Not only has the volume of fish gone down drastically, but wildlife researcher Faiyaz A Khudsar found the diversity of fish itself had been affected. “Major carp species have disappeared, and scavengers like the Asian stinking fish, tilapia and African catfish have increased,“ he says.

No wonder the fishermen are nostalgic about the good old days. The Haldars, Ratan, 61, and Sukumar, 55, came to Delhi in 1965, married in the city and made the Yamuna the pivot of their lives. “The water was deep and very clean then and there was abundant fish.It made sense to move to Delhi for fishing,“ recalls Sukumar.He remembers his friend Liaqat who earned a living ferrying people. “There were many boatmen then, but after 1988 the water became too shallow for boating,“ he adds. Naturally, boatmaking as a business too suffered a silent death.

“Our children will continue to live in this city,“ says Sukumar. And then delivers the requiem for a way of life: “They may never fish for a living though.”

Dhobi ghat/ washermen's colony dwindles

The Times of India, Oct 27 2015

Jayashree Nandi

Dhobi ghat has lost its shine

Laundry stopped coming a long time ago because of the grime and stink of river water. Now old clothes to be recycled given chemical bath before being washed

Just ahead of Loha Pul near Wazira bad, two ageing men work desultorily on the banks of the Yamuna, whose waters run dark and fetid along the dhobi ghat there. Mohammed Sharif, 65, and Mohammed Jamil, 70, heft heavy, damp sheets over their heads and dunk them into a milky concoction of bleach, alum and other compounds before rinsing them in the river. Without this bath in the chemicals, the old men know they will never get the filth out of the cloth because a prolonged soak in the effluent-laced river water leaves a grimy patina on any laundry . The work wasn't as back-breaking some years ago. When younger, the two Mohammeds helped their fathers at the ghat.“The water was clean and the river was just right for the dhobi business,“ sighs Sharif. He philosophically accepts that the washing machine has overwhelmed the dhobi's business across the country, but, the sexagenarian quietly adds, “the Yamuna dhobis have been the worst affected“. He isn't wrong. Though the washermen continue with the work because it is the only way they know how to keep hunger from their doors, their income has shrunk miserably . Households have stopped giving their dirty clothes to the riverbank dhobis because after a wash in the Yamuna, the garments return reeking of sewage and often with darkish stains left by the polluted water. Pushed to the edge and virtually out of business, many Yamuna dhobis now only get the custom of old-cloth sellers.It is common enough in Delhi to see the itinerant peddlers who exchange old clothing for steel utensils. The pieces collected are hawked to shopkeepers, who in turn sell them to factories to use as raw material for various products. The shops first send their piles to the dhobis for a wash at a rupee and a half per item. Suraj Pal, 55, has just received a saffron-coloured dump of such scraps.“This has come from Kolkata and probably has been discarded by sanyasins. There must be a tonne of them here,“ he says, grateful there is some money he can take home today . Downriver, the locality behind the Shas tri Park metro station is luckier because some people still send their soiled clothes to the dhobis, who charge them Rs 5 apiece.

Once a washermen's colony, however, there are a mere five families left in the business now. Mohammed Mustafa, one of them, installed a hand pump to draw cleaner water, but even that is polluted, he claims. “Earlier hospitals used to give us their bed linen, but fear of infection from the effluent has stopped them and our customer base is becoming smaller,“ he says. Social activists wonder why the government has done so little to rehabilitate the community . “The government should provide alternatives until there is adequate safe water for them to return to their profession,“ suggests Manoj Misra, convenor of the Yamuna JiyeAbhiyan, a group working to restore the Yamuna. But the reality is depressing. “Hamarisunwaikabhinahihoti (Our complaints are never considered),“ says Mohammed Shakil, Sharif 's son. “In fact, the government gave us an indirect message to relocate and stop washing in the Yamuna.“ The young man's reference is to the demolition of the dhobi ghats at LohaPul in 2006 as part of the court-appointed Justice Usha Mehra Committee's orders on removal of encroachments within 300 metres of the Yamuna. “Can you believe that as a young man I drank the Yamuna's water?“ says Sharif, rolling his eyes. “I could never have imagined that washing clothes in that water would leave a stink.“ Sharif can no longer afford, as he once did, to send out a cart in the morning, ringing a bell to attract the attention of customers. “Over time, people in the Walled City started sending their laundry to dhobis who had borewells,“ he says, realising perhaps that in time, the Yamuna will cease altogether to be a home for dhobis.

Religious offerings consumed by riverbank dwellers

Anindya Chattopadhyay & Jayashree Nandi TNN 2013/06/15

Fishing for food in dangerous waters

Diver boys on the Yamuna bank take a dip in the stinking pool of sewage every day, and often come back with lunch for their families.

Some find a huge sack of dal and the family enjoys it for days. Others sometimes pull out bags of rice, fruits, vegetables, and packs of ghee from the offerings made to the Yamuna and these make their meals on most days. It doesn’t matter if the food was soaked in the most toxic effluents; hunger is overpowering. The Yamuna, though foaming with chemicals, is often a source of nutrition for communities living by it.

Some youths have grown up on the food from the river. “We get oranges, bananas, mangoes, dal, rice, jowar, sugar.I havebeen eating these for years now and it doesn’t bother me,” one of them says.

They also get ‘precious’ items. They pull out coins, metal idols and very rarely even gold objects. A 15-year-old fished out a shiny object and sold it to the scrap-dealer in his colony for Rs 3,000. Some of his neighbours later told him it was made of gold.

Many of them have to submit all items to a contractor who pays them a nominal amount. “We have to give him what we get but we get to keep the food items,” says Paswa who recently found 12kg steel but “the contractor gave me Rs 200 for it”.

Girls are also excited about the day’s lucky pick. “If we get fruits, we are happy. They are usually fresh,” says Tulsi, who goes to an MCD school.

But not everyone can bring back lunch or goodies from the river — these diver boys are usually hired by police to look for corpses or save people from drowning.

Kyari Kashyap, a veteran among the divers, has been in the business for 30 years. “People conduct pujas here and throw a lot of prasad in the river. Why can’t the poor collect them?” Kyari is, however, concerned about pollution levels. He agrees that the food from the river may be unhealthy but that won’t stop people from collecting, he says.