Ram Leela, Ramleela, Ramlila

(→Mumtaznagar Ramlila) |

m (Pdewan moved page Ram Leela to Ramleela, Ram Leela, Ramlila without leaving a redirect) |

Revision as of 16:10, 9 October 2016

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Agra

Muslim actors

In Agra, Nizamuddin continues to rock the Ramlila stage. He's been doing key roles for the last five years and is this time essaying the role of Janak, the father of Sita no less.

It wasn't always that easy for Nizamuddin though. During his early years in the Ramlila theatre, he too faced protests and opposition. But he stood his ground.

In fact, another Muslim will play the part of Bharat alongside him [in 2016].

The 55-year-old, who is a trackman at Agra Cantonment station in the north central railway zone, never took any acting classes but has been bagging top-notch roles since 2010.

Speaking to TOI, Nizamuddin said, “Getting a role in the Ramlila has always been a matter of pride for me, but things haven't been easy... scores of people from my own community raised questions about my faith in Islam. I was almost thrown out. I believe that there is no sin in a Muslim man acting in a Hindu play. After all, Ramlila talks about peace and the triumph of good over evil.“

Delhi

The Luv Kush Ramlila

The Times of India, October 18, 2015

Dharvi Vaid Months of effort go into the staging of a Ramlila. TOI takes a peek backstage

Gasps and cheers fill the ground when Ganesha appears in the night sky in a psychedelic burst of light. Dancers in shiny , colourful costumes keep step as a hydraulic crane lowers the idol to the accompaniment of a live bhajan. The crowd is on its feet humming Ganesh Vandana while tiny, piercing phone flashes go off all around. The night is off to a successful start at the Luv Kush Ramlila outside Red Fort. The legend cannot change, but every year the many Ramlila committees in the city vie to outdo each other in its treatment. Ramlilas get bigger and, arguably , better. And this year's Lav Kush Ramlila--now in its 37th year--is the biggest ever. Mounted with a budget of Rs 3 crore, it has 30 television and Bollywood actors in the cast, special effects and stunts never seen before.

But it's one thing to plan big and another to ensure that the show runs as planned. And that means starting work months in advance. It is impossible to tell from the effortless scenes how much work has gone into making them possible. TOI goes behind the scenes to give you a peek into the making of a mega Ramlila.

The Luv Kush Ramlila Committee, which organized its first Ramlila in 1979, starts planning the year's theme and new elements in January , followed by decisions about the design of sets and the look of the artistes. Then comes the shopping in Sadar Bazaar. “It takes months to shop because we have to buy everything from the dresses to the props,“ says Sanjay Sharma, who runs the show backstage.

The best actors have to be engaged early . This year, they have hired 70 actors and 15 dancers.“Most of them come from Filmistan in Karol Bagh and are seasoned Ramlila actors,“ says Lovekesh Dhaliwal, assistant director of the show and a 12year veteran.

Auditions follow and roles are assigned, but the actors don't go into dialogue boot camp until a month before Navratras.“It is not television. There are no breaks, cuts and edits. We perform live and so there is no room for er so there is no room for error,“ says Dhaliwal. Some dialogues run into pages and are peppered with Sanskrit slokas. Voice modulation is the key to keep them from becoming boring monologues.

“To play a rakshasa, you need a booming voice that strikes fear in the audience; for a positive role it has to be deep but mellifluous,“ says Sunny Verma, who is playing Lakshmana.

Most artistes are not pros. They have day jobs but are passionate about acting. Which explains why they put in weeks of labour for a pittance. “We get only about Rs 10,000 for the entire Ramlila, but do it as an act of devotion,“ says a woman artiste who has been in Ramlilas for the past 10 years. Verma is a supervisor in a private firm. “I try to finish my work early so that I can come here and practise,“ he says. It's tougher for actors who play multiple roles.

Dhaliwal stays backstage but as the prompter he keeps the show ticking over when artistes falter.The Ramlila actors still don't use in-ear devices.“Goof-ups happen all the time. The lights and the audience make actors nervous,“ he says.

Kumar Gowda, who worked with BR Films in the hit TV series Mahabharata, is the stunts and special effects whiz. “I have worked with Rajinikanth and Kamal Hassan but a live performance is a different kind of challenge. A Ramlila action sequence is about magic, and fire and aerial acts, not fistfights.“

Gowda has brought equipment and professional stuntmen from Mumbai and has several scenes t e a l e r s lined up. He will show Ahilya transform into a living person from a statue, Hanuman fly over the audience and Meghnad appear at different places in mid-air using spotlights. The audience has already seen a stuntman on fire. Dangerous acts have made strong harnesses, safety mats, sand, water and fire extinguishers musthaves on the stage.

Costumes are as important as artistes and props in bringing alive a performance. The Luv Kush Ramlila has 18 trunks full of clothes and jewellery, and a resident tailor for last-minute fixes. “Each lehanga costs from Rs 5,000 to Rs 10,000 depending on how ornate it is,“ says Nandita Rani, one of the two women who look after costumes. The Ramlila has about 40 female artistes.

There are four makeup artists for the cast. One of them, Sumit Kumar, was to play Rama before TV actor Gagan Malik was roped in for the role. The Ramlila look requires thick coats of foundation and swatches of lipstick. “Makeup has to be bright enough for the expressions to be visible,“ says Kumar. And it has its nuances too. “The tilak has to be different for different characters. Lakshmana's eyebrows have to be defined and sleek while a rakshasa's have to be thick and drooping.“

Stunts and fine acts draw crowds but a Ramlila is also a night out for the audience, and it's incomplete without a `mela' atmosphere. There have to be rides and eats and knickknacks, and the grounds of the Luv Kush Ramlila have it all, from Ferris wheels to faluda. The curtain comes down late at night but when children return home armed with toy bows, arrows, swords and maces from the mela, the show resumes at home in the morning.

The Muslim contribution

Paras Singh, No Lakshman rekha for these Muslims. Oct 08 2016 : The Times of India

The first Ramlila group in the capital was set up [around A.D. 1850] by Mughal king Bahadur Shah Zafar.

Shri Navyuwak Ramleela

“I started at five by joining Ram's vanar sena,“ chuckles Sadiq Hussain, having graduated to bigger roles. For 15 years now he has been assigned the role of Lakshman in Shri Navyuwak Ramleela Committee's mythological.

Sporting a vermillion tilak, Hussain, 30, a resident of Kashmiri Gate, says, “I have never faced any problem here.The organisers as well as my family have always supported me.“ When he got married a month and a half ago, Hussain wondered whether he should be preoccupied with the Ramlila so soon after marriage, but his wife firmly put him in place by telling him, “You've been doing it for so long, why should you stop now?“ A couple of days ago, his wife and mother inaugurated the Sita swayamvar act by igniting a lamp. His brother Manzar Hussain used to act the role of Ravana.

Sri Nav Dharmik Ramleela

Mujib-ur-Rahman,27, Kumbhkaran at the Sri Nav Dharmik Ramleela, shared a similar experience. “I felt mummypapa would not let me act, but they did. I once lied and told them I was acting as Ram wondering if they'd let me play a Hindu god. But they had no problems.“

Luv Kush Ramlila

Jalaj Sharma, Hussain's director, says that Muslims participating in the Ramlila hasn't been a problem in Delhi.“And by Lord Ram's blessings, it will remain so in future,“ stresses Sharma. His optimism is founded on the ready acceptance of Muslim as artists, craftsmen and organisers of the capital's Ramlilas.Why , the star-studded Luv Kush Ramlila on Red Fort lawns has three prominent Muslims: Raza Murad as Janak, Farheen as Sunaina and Ali Khan as Meghnad. Ashok Agarwal, chairman of the committee there, points out that Muslim families of Old Delhi generously donate to these annual shows.

“Ramayan jodne ka kaam karti hai,“ says Hussain. [The Ramayan brings people together.]

Kheriya (Firozabad)

In Firozabad district's Kheriya village, the annual Ramleela is funded and enacted with a great deal of enthusiasm by Muslims. The man playing Ram, Shamshad Ali, does the ritual Islamic wazu before he steps on to t h e ramshackle stage at the local Shiva temple. The props and costumes come from local Muslim homes as well, the curtains from a daadi, and the blouse from a naani.Jokes pepper the staging. An extra in a state of trance is beaten up with the question: “Tu Hindu bhoot hai ki Musalman? Bata...bata.“

The Times of India, Dec 06 2015

Malini Nair

Spicing up Ramlila with thumkas and qawwali

In Firozabad's Kheriya village, the Ramlila's primarily Muslim cast combines humour, dance, music & acrobatics Shamshad Ali does the wazu, the sacred ablution, and heads for prayers at the village masjid, and in the next instant he stands on a ramshackle green room in the courtyard of the Hanuman temple transformed into Ram. He is among the many Muslims of Kheriya, a village in the glass-making district of Firozabad, UP, who enthusiastically join the unique Ramlila performance every year, telling the epic over 17 long days. Ramlila everywhere is highly folksy in nature, with elements from nautanki and Bollywood thrown in for good measure. But nothing will prepare you for the total riot that is Kheriya Ramlila, recently performed at the IGNCA in Delhi. And the creative camaraderie that marks the production is unfettered by any communal sentiments.

“All the major characters are played by Muslim males. The village audiences don't really care about religion -they just found the talent they needed to play Ram or Hanuman or a dholakiya or acrobat. In fact, they are not even beyond lampooning the whole Hindu-Muslim debate,“ says Molly Kaushal, professor, performance studies, at the IGNCA.

Kheriya Ramlila is totally owned by the people of the village, written up as they want, played on the artistic whims of the cast, dotted with humour, satire and impromptu acts. There really is no script here to talk of, though the play is based loosely on Radheysham's Ramayan, the text used by Ramlilas across most of the Hindi speak ing belt. For the rest, expect the unexpected.

Midway through the play , Sunil Kumar, a cross-dresser, enters the stage and asks the rag-tag bunch of characters trying without much luck to summon the devi in their midst: Is this how you tempt her to earth? Let me show you how. And breaks into some wildly provocative thumkas that has the crowd in splits. There is even a passing comic sutradhar, who is allowed every liberty including bursting into a Kishore Kumar qawwali -Haal kya hai dilon ka na poochho sanam.

Nothing much is sacred on this dais where Ram, Sita and Laxman sit patiently suffering the goings-on. Even when they enter the picture there is no stopping the gags. Sunil Kumar, now Soorpanakha, is ogling at Ram who tells her: “Devi, main shaadi shuda hoon.“ “Mujhe devi mat bula, woh to mandir main baithti hai. Mujhse direct baat kar,“ she saucily retorts.

Most of the actors are farm hands, labourers, and those who do assorted jobs. For them the yearly show is a break from drudgery. Kheriya Ramlila is a creation of the 1970s. Up until then the village had to troop to neighbouring Ramlilas. What they had, however, was swang, a popular folk form that involves mimicry, a whole lot of clowning around, jokes, songs and dance. The swang troupe once tried its hand at doing Ramlila and the show went so well the village decided to put its spare resources to staging it every year at Dassera.

Humour still remains a big element of Kheriya Ramlila. An extra in a state of trance is being beaten up with the question: “Tu Hindu bhoot hai ki Musalman? Bata...bata..“

Soon an Aghori baba you are not likely to see at any Ramlila joins the action, straight from the shamshan bhoomi, painted in the grey of the ashes and red of the pyres. Exactly what is he doing in the middle of divine storytell ing? Nothing much, but it is scary and jolly good fun. Ram, Sita and Laxman seem to be having a good time too.

Malabar/ Mappila Ramayanam

Malini Nair, When Ramlila begins with a wazu, Oct 09 2016 : The Times of India

Among the most fascinating Muslim interpretations is the Mappila Ramayanam of Kerala's Malabar region. It is hard to trace its historicity or even authorship of these songs, but sometime in the early 1930s, a Brahmin teen had become an ardent fan of a Malabar Muslim minstrel, nicknamed `pranthan (lunatic) Hasankutty'. He memorized 148 lines of a lyrical mish mash that later came to be known as Mappila Ramayana paattu (songs). The teen became a leading Kerala folklorist TH Kunhiraman Nambiar. His collection of Malabar Ramayana ballads merrily dip into the local culture and even weave in contemporary ideas into the telling of the story. “The Mappila Ramayan am is replete with images and expressions alluding to the Muslim way of life such as kozhi (chicken) biriyani, beevi Shurpanakha etc,“ says scholar Azeez Tharuvana in his acclaimed work Wayanadan Ramayanam (the Ramayanas of Wayanad).

The Muslim references are often integrated into the Ramayana with humour. For instance, Shurpanakha exhorting Rama to accept her cites the Shariya on why he doesn't have to stay faithful to one wife.

Tharuvana believes that Ramayana in these cases becomes more of a cultural, rather than religious, text. “Just as the adivasis of Wayanad have turned the story of Rama into something set in their hills and villages, the Mappila Ramayanam sets itself in the context of Malabar Muslims. The Indonesian Muslims have done this with Hikayat Seri Rama so have the Malaysians and Filipino Muslims,“ he points out.

Mewat/ Meo jogis

Malini Nair, When Ramlila begins with a wazu, Oct 09 2016 : The Times of India

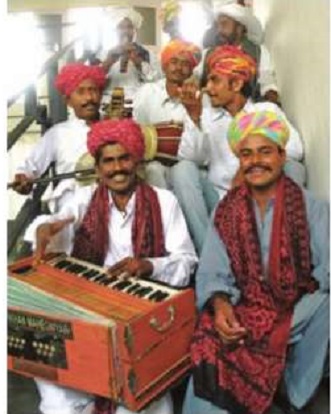

Ever since he can remember Umar Farooq Mewati has been singing Lanka Chadhai, a ballad in praise of Ram's triumph over Ravana. He belongs to a band of Muslim minstrels called Meo jogis who are often invited by Muslim jajmans (patrons) in and around Alwar in Rajasthan to perform on festive and family occasions.

But in recent years, Mewati and other Meo jogis have been finding it hard to hang on to their art. “We have been hit by the increasing kattarvad (fundamentalism) in the region among both communities -Hindus as well as Muslims. Hajis are now telling us that music is haram; some of them tell us to take the money but leave without singing. This is an oral tradition, if we don't practise it, it will die,“ says Mewati.

A nostalgic Siddiqui who was to play Marich in his village Ramleela in western UP, was forced off the stage by the shrill racket of the local Shiv Sena. Sena men claimed that no Muslim had played roles in the Budhana Ramleela for decades. But across UP -especially in Kanpur, Lucknow and Muradabad -there are several living and thriving examples of Muslim participation in amateur Ramleelas.

Mumtaznagar Ramlila

The Times of India, Oct 19 2015

Muslims holding Ramlila here since 1963

For 50-odd years Mumtaznagar Ramlila here has exemplified inter-com munity goodwill. Held in a Muslim neighbourhood, this Ramlila has been managed and largely enacted by Mus lims. For two years, however Muslims have been barred from playing main charac ters like Ram, Sita, Laksh man and Hanuman. The rea son: they eat meat. “Some local people object ed to Muslims performing lead roles in Ramlila,“ said Majid Ali, president of the Ramlila committee.

“Their objection was that since Muslims eat meat, they shouldn't enact the role of gods. When we came to know about the objections, we eased them out,“ Ali told TOI. Baldhari Yadav, a senior member of the Mum taznagar Ramlila committee, said women spectators worship the actors playing Lord Ram, Lakhsman, Sita and other gods by touching their feet and seeking their blessings.

Keeping in view their re ligiosity, Muslims who eat meat have been replaced by Hindus who, even if they are meat-eaters, turn vegetarians during Navratra. “But Muslims continue to play smaller parts,“ Yadav said.

The Ramlila here has sustained the same zeal since 1963. Tailor Naseem, with his limited income, starts taking extra orders before Navratra to fund the 10-day affair. He is supported by other Muslims.

Muslims’ Ram Leelas

In India, Muslims across regions have been retelling, singing and performing stories from the Ramayana as well as participating in local performances of Ramleela. The Muslim Manganiyars of Rajasthan tell Ram Katha as do the Muslim patuas skilled in patachitra in West Bengal. Most of the crafts associated with Ramleela in north India --the making of the Ravana effigy, the zardozi, mukut, costumes, the toy replicas of `weapons' -are all considered the domain of Muslim artisans.