Population growth and fertility rate: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

In brief

The Times of India, 28 March 2013

Saswati Mukherjee

South India lags national fertility rate, slows population boom

India's burgeoning population appears to be both a problem and an advantage. Very soon, the southern states are likely to stare at an un-Indian situation: a shrinking populace, owing to a sharp dip in the fertility rate of women.

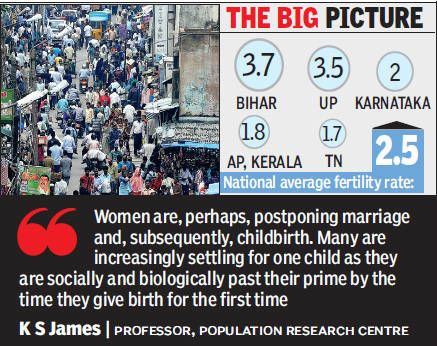

Analyzing the 2011 Census data, the Population Research Centre of the Bangalore-based Institute for Social and Economic Change found that many southern districts, a significant number of them in Karnataka, have recorded fertility rates lower than the national average. The study says turnaround will happen soon.

Half of India's 1.21 billion population comprises women, and the national average fertility rate stands at 2.5, slightly higher than the targeted 2. The theory is simple: two children replace two parents, and the population remains stagnant.

Experts say women in most southern states appear to be settling for one child, pulling down the average fertility rate.

Karnataka's overall fertility rate stands at 2, but there's an interesting variation in the districts. In Udupi, for instance, the fertility rate is 1.2; in Hassan, Mandya and Chikmagalur, it's 1.4; in Dakshina Kannada and Kodagu, it's 1.5. Bangalore, at 1.7, is well below the national average. Some districts, though, have high fertility rates: Bijapur stands at 3, and Bidar at 2.7.

The other South Indian states of Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu are in the sub-2 category.

"Women are, perhaps, postponing marriage and, subsequently, childbirth. Many are increasingly settling for one child as they are socially and biologically past their prime by the time they give birth for the first time," said K S James, professor, Population Research Centre, who led the data analysis.

SUDDEN DISARRAY

What happens if the population shrinks? Arresting the spiralling population growth rate has always topped the nation's agenda. Experts, though, beg to differ. A sudden turnaround in population could lead to demographic disarray, they say. "The first result of negative population growth is the number of elderly people goes up and young people comes down. This means there are fewer youngsters to take care of our elderly," said Prof. K S James.

WOMEN MAKE INFORMED CHOICE

Experts say women make an informed choice to have a single child, given the high literacy level in the southern states.

"Often, this is to give the lone child a good quality of life. Keeping in mind the high cost of living, young couples are increasingly settling for one child," said retired ISEC professor KNM Raju.

With both men and women being educated, they make informed decisions. "The woman's decision today is well thought out, and she has her partner's support too," said Raju.

The implication could be quite significant. If both partners in a marriage are themselves from single-child families, the responsibility of taking care of both sets of parents falls on them. "Parents these days are not dependent on their children financially. It's the psychological dependence which will be missed the most," Raju pointed out.

Experts attribute this trend to the southern states being open to change. "It's their willingness to accept social changes that work for them," said Raju.

NORTH-SOUTH DIVIDE

Unlike their southern counterparts, the northern states are showing an increase in fertility rate. The country is evenly poised, with half the country adhering to the national average and below, and the other half exceeding the figure.

Experts point to high awareness and education levels and successful family planning programmes in the southern states for low fertility rate figures. Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar, though, have the highest fertility rates in the country, experts say.

Fertility rate

1950-2020: India

India vis-à-vis Bangladesh, China, Iran, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and First World countries, 1950-2020.

From: July 2, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic:

India’s total fertility rate, 1950-2020

India vis-à-vis Bangladesh, China, Iran, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and First World countries, 1950-2020.

1950-2019: India, Africa, China, World

i) Total fertility rate; and

ii) Population growth.

Total fertility rate in India:

a) religion-wise, 2005-16.

b) state-wise, 2011.

The sex ration in India, 2017.

From: August 17, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic, ‘ India, Africa, China, World, 1950-2019:

i) Total fertility rate; and

ii) Population growth.

Total fertility rate in India:

a) religion-wise, 2005-16.

b) state-wise, 2011.

The sex ration in India, 2017. ’

2021

Sushmi Dey, June 9, 2022: The Times of India

New Delhi: Union health minister Mansukh Mandaviya is strongly opposed to the idea of regulating population by force at a time when campaigns and awareness creation are showing results and have led to a dip in numbers, top official sources said.

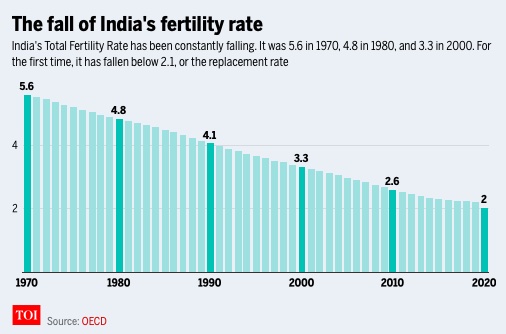

India’s total fertility rate (TFR) has declined from 2. 2 in 2015-16 to 2. 0 in 2019-21 — indicating average number of children per woman — which is below the replacement fertility level of 2. 1. The latest NFHS-5 data also shows that women of all religious communities are now on average giving birth to fewer children than in the past.

The health ministry’s stand assumes significance in the wake of recent comments by junior minister for food processing Prahlad Patel that there could soon be a law on population control. Patel's remark sparked a buzz about a shift from the stand government had taken in Parliament this year where Mandaviya argued against the need for a law in view of the decline in population growth. It grew when BJP chief J P Nadda recently said that discussions have been on and that the process of making a law takes time.

When asked about Nadda's comment, health ministry officials refused to comment saying that they are unaware of the context in which he spoke and; more specifically, the question that he responded to. They, however, felt that Nadda’s reference could be to the aspiration of BJP governments in UP and Assam to have a population policy. According to NFHS-5 data, while India has made significant progress in population control measures in recent times, there are wide inter-regional variations with five states still not having achieved a replacement level of fertility of 2. 1. Bihar (2. 98), Meghalaya (2. 91), UP (2. 35), Jharkhand (2. 26) and Manipur (2. 17) are the five states, according to the data conducted from 2019-21.

In April this year, Mandaviya had firmly opposed a private member bill by BJP’s Rakesh Sinha in Parliament, which sought to enforce a two-child rule with penal provisions for violations to stabilise the country’s population.

Mandaviya had told Rajya Sabha that instead of using “force (jabran)”, the government had successfully used awareness and health campaigns to achieve population control. The bill was withdrawn following Mandaviya’s intervention.

Arguing against the need for a population control law, health ministry officials say the results of the National Family Health Survey and census are indicative that population growth has declined over the years and that the government’s efforts are in the right direction.

China, South Asia: trends, 1995-2015

The Times of India, Apr 18 2017

20 years ago India added an Australia to its population every year

Twenty years ago, India added the equivalent of Australia's population to the number of Indians every year, while China added a Cameroon. Both countries have been able to bring about a significant reduction in the population growth rate and absolute increase in population since then. But China has done much better, almost halving the number of people it adds to its population

Education and TFR

2013-2018

Ambika Pandit, July 1, 2020: The Times of India

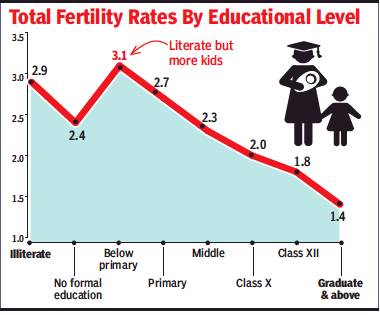

As the total fertility rate (TFR) reflects a decline from 5.2 in 1971 to 2.2 in 2018, the Sample Registration System Statistical Report 2018 highlights how not just age but education levels of women have had a direct impact on fertility. At the national level, TFR for illiterate women in 2018 was 3. This is much higher than the literate group, which has a TFR of 2.1 and has seen a decline with the increase in the level of education.

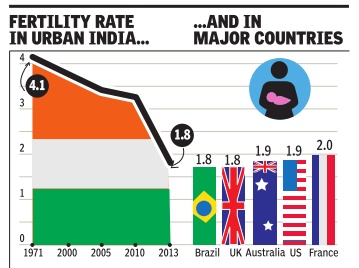

TFR indicates the average number of children expected to be born to a woman. Going by the data, a rural woman (having a TFR of 2.4) at the national level would have about one child more than an urban woman (having a TFR of 1.7) on an average.

Fertility rate, region-wise

In urban India lower than in US, Oz, France

The Times of India, May 14 2016

Fertility rate in India's cities lower than in US, Oz, France

Atul Thakur

For most people, the gene ral perception about In dia is of a country sitting on a ticking population bomb.This notion, however, seems to be somewhat misplaced, at least in the context of the country's urban population where the fertility rate -the number of children born per woman -has fallen to levels lower even than those in countries like the US, France, Australia and New Zealand.

Data from the Sample Re gistration Survey (SRS) shows that since 2006, total fertility rate (TFR) in urban areas has touched two children per woman and from 2010, has fallen below that level.That means there aren't enough children born in Indian cities to replace the existing population of their parents.For advanced economies, this `replacement rate' is generally estimated at an average of 2.1. Because of the higher infant mortality rate (IMR) in developing countries, the replacement level fertility rate would be slightly higher and so Indian cities seems to have touched the point where the population would start declining in the absence of migration from rural areas.

Is this an alarming trend?

Experts don't think so: “2.1 is more like a synthetic number.During fertility transition, the total fertility could go below 2.1 and stabilise in a decade or two“, says population expert Purushottam M Kulkarni, who recently retired from JNU. Ravinder Kaur, professor of sociology and social anthropology at IIT Delhi, points out a similar pattern of low fertility across Asia and in Catholic southern Europe.

“Although the IMR is substantially high compared to western countries, it is not as alarming as it used to be and there is a general confidence in the population that the chances of a child's survival are higher compared to the past decades and hence fertility is low,“ added Kulkarni. Data shows that in 1971, the infant mortality rate was 82 (per 1000 births) and total fertility rate was 4.1for urban India.

Though the rural fertility rate of 2.5 is higher, it too has witnessed a steep decline over the years. In 1971, the rural fertility rate was 5.4, nearly double its present level. Incidentally , in 1952, India became the first country in the world to launch a family planning programme. The sustained government campaign, better access to healthcare facilities, higher female literacy and more participation of women in the workforce have all worked in lowering fertility rates in cities. Many couples prefer one child, although this is not the general norm.

“The fewer children preference allows the middle class to rise up the social ladder by investing more in them is gendered with preference of sons over daughters. Sons bring dowries and investing in their education helps families move up socially ,“ says Kaur. Professor Kulkarni, however, points out that there are regional differences as southern states have lower fertility and better sex ratios.

All- India 2015-16; Uttar Pradesh: 1998-2016; Rural India: 2015-20

Priyanka Mukherjee, July 15, 2021: The Times of India

In 1950-55, India’s total fertility rate was 5.9. The

rate has declined steadily since 1975 to touch 2.2.

TFR

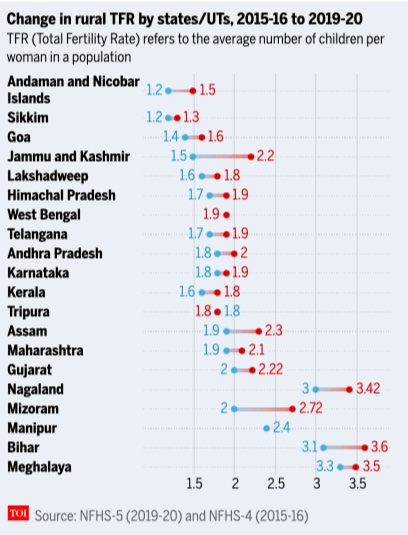

As per the Fifth National Family Health Survey (NFHS) the total fertility rate has decreased across the majority of the states. According to the data, only three states — Manipur (2.2), Meghalaya (2.9) and Bihar (3.0) — have TFR above replacement levels.

The NFHS-4 data on birth order showed that the highest proportion of births was among women with no schooling.

The lowest proportion of births of the third or fourth child or beyond was among women who had completed 12 years of schooling. According to the census, Muslims have the lowest literacy level (37%).

Rural India, state-wise

From: Priyanka Mukherjee, July 15, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

Change in rural TFR by states/ UTs, 2015-20

Uttar Pradesh fertility rate

From: Priyanka Mukherjee, July 15, 2021: The Times of India

Data from the National Family Healthy Survey done in 2019-20 (NFHS-5) has not yet been released for Uttar Pradesh. But going by National Family Health Survey-4 (NFHS-4) (2015- 16), the fertility rate in Uttar Pradesh has declined from 4.1 to 2.7 during 1998 to 2016. However, this decrease is not uniformly spread, the rural areas have marginally high TFR.

As per NFHS-4 data of 2015-16, the total fertility

rate for urban areas in Uttar Pradesh was 2.1

while for rural areas it was 3.0. UP's TFR was 3.8

in 2005-06 (NFHS-3). In 1998-99, UP’s total

fertility rate was 4.01.

Religion-wise, the fertility of Hindus was 2.7 in 2015-16 and that of Muslims was 3.1.

Sushmita Choudhury and Rajesh Sharma

TIMESOFINDIA.COM

Jul 15, 2021, 11:30 IST

Uttar Pradesh is India’s most populous state with a population of nearly 20 crore, according to Census 2011. That’s around 16.5% of the country’s population. The state’s population increased by 20.23% from 16.62 crore in the 2001 census — which is much higher than India’s decadal population growth (17.7%) . The latest Sample Registration System of 2018 shows that UP’s General Fertility Rate (GFR), defined as the number of live births per thousand women in the reproductive age group of 15-49 years, was 91.4 against a national average of 70.4. This is second only to Bihar.

UP’s TFR in 2018 was the

highest in the country at 2.9, against the national average of 2.2. TFR indicates the average number of children expected to be born

per woman during the entire span of her reproductive period.

According to the Union government, 28 out of 36 States and Union Territories have already achieved the level of 2.1 or less.

Dr Alpana Sharma, general manager - family planning, National Health Mission, UP, pointed out that the number of women adopting family planning measures in the state had increased significantly over the years. In 2017, 23,217 women had registered for Antara contraceptive injections and by FY20, the figure had snowballed to 3.4 lakh.

UP: religion wise, 2001- 2011

The NFHS-4 showed that the TFR of the Muslims in Uttar Pradesh is 3.10, and that for Hindus is 2.67, compared to the national average of 2.2. But lest anyone shouts demographic shift, it's also important to analyse the population size by religion. According to Census 2011, Hinduism is the majority religion in the state with 79.73% followers while the number of Muslims is much lower at (19.26%).

This means that although Muslim women are bearing more children in the state, there are four times more Hindu women, so population growth is not driven by any one religion. In fact, as demography and population health specialist Saswata Ghosh pointed out in his research paper titled Hindu-Muslim Fertility Differentials in Major States of India, while Hindu women saw an absolute decline in TFR of 1.5 between 2001 and 2011, the same for Muslim women was 1.9.

The share of the other religions in UP is miniscule — Sikhs (0.32%), Christians (0.18%), Jains (0.11%), and Buddhists (0.10%).

Moreover, these religions are seeing fertility rates below the replacement level of 2.1 across India.

India’s largest states, 1971-2011

From: Sushmita Choudhury and Rajesh Sharma Why UP is talking population control July 15, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

The population of India’s largest states, 1971-2011

Decadal dip in TFR, state-wise, 2006-18

From: Sushmita Choudhury and Rajesh Sharma Why UP is talking population control July 15, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

The Decadal dip in TFR, state-wise, 2006-18

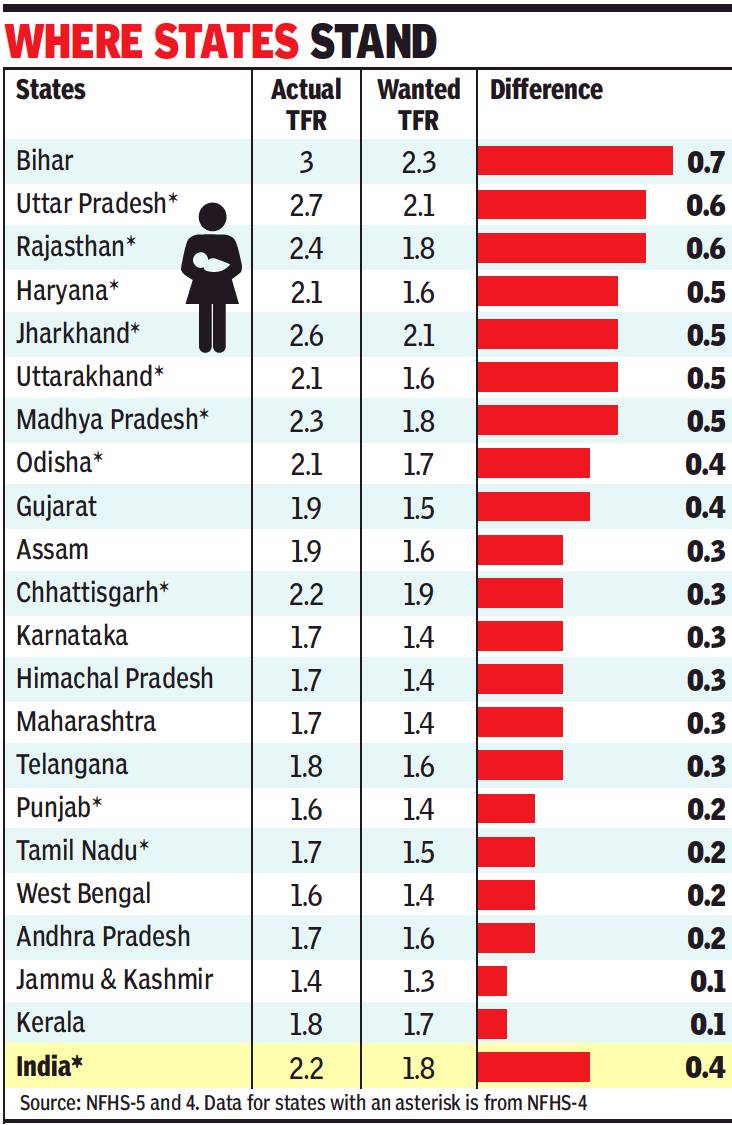

2005-16: wanted TFR vs. actual TFR, state-wise

Rema Nagarajan, July 22, 2021: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, July 22, 2021: The Times of India

If adequate and accessible family planning services were provided to all women who need them, the country might have achieved a fertility rate lower than replacement level as far back as 2005-06. According to the National Family Health survey (NFHS) report of 2015-16, the total wanted fertility rate or an estimate of what the fertility rate would be if all unwanted births were avoided, was 1.9 in the 2005-06 survey and 1.8 in 2015-16. This raises the question of whether it makes sense to penalise women or the people for the failure of governments to provide basic health services.

In the latest NFHS survey of 2019-20, the wanted fertility rate did not touch 2 in any of the larger states for which data has been released, barring Bihar, where it was 2.3 compared to a total fertility rate of 3. The reports of several states including Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Punjab have not been released yet. India’s total wanted fertility rate declined from 2.6 in 1993 to 1.8 in 2016.

The replacement level fertility rate is 2.1 children per woman, a level at which a population exactly replaces itself from one generation to the next. India’s fertility rate in 2015-16 was 2.2 and the partial data available for 2019-20 suggests it is likely to have dipped below replacement level. When the total fertility rate of a country falls below 2.1, its population starts shrinking after a few years. This would have started happening in 2005-06 if the government could improve services in health and education.

According to the 2015-16 survey, there wasn’t a single religious community or caste for which the total wanted fertility was above 2 children. Total wanted fertility rate was 2.3 only for the poorest and those who had no schooling.

It was also estimated that 13% of married women had an unmet need for family planning and there hasn’t been a significant decline in this unmet demand over a decade. This was as high as 22% among married women in the 15-24 age group. The unmet need for family planning refers to women of child-bearing age who wished to postpone the next birth (spacing) or stop childbearing but couldn’t. Among larger states, unmet need for family planning was the highest in Bihar (21%) followed by Jharkhand and UP, where it was 18%.

Family planning resources aside, if India ensured at least five years of schooling or primary education for its girls, its fertility rate could be well below replacement level. According to the 2015-16 survey, the total wanted fertility rate for women with no schooling was 2.3, which dropped to1.9 among those with five years of schooling and1.5 for women with over 12 years of schooling.

Similarly, if India managed to lift the poorest 20% out of poverty, the fertility rate would be about 1.9. The NFHS-4 survey showed that the total wanted fertility rate of the poorest 20% of the population was 2.3 compared to 1.9 for the next wealth quintile and 1.4 for the wealthiest 20%.

It is also no coincidence that the states with the highest wanted fertility rate are also the ones with the worst under-five mortality or the probability of dying by age five per 1,000 live births. It is well established that couples tend to have more children when the survival of their children is uncertain. Bihar, where the total wanted fertility rate was 2.3, had the highest under-five mortality rate of 56.4, which means nearly 6% of children born live die before five years of age. And that’s the average for the state. For the poorest, the rate would be much higher. Similarly in UP, where the total wanted fertility rate in 2015-16 was 2.1, under-five mortality was 78.

2017: a little education is worse than none

Rema Nagarajan, August 12, 2019: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, August 12, 2019: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, August 12, 2019: The Times of India

The higher the educational level of a woman, the lower the total number of children she will have, according to conventional wisdom. However, recently released official data from 2017 on the total fertility rate (TFR) or the average number of children born to a woman over her lifetime shows the connection may be more complex. For one, the culture of a state might be a greater determinant of fertility, with illiterate rural women in Tamil Nadu having a lower fertility rate than urban graduates in Uttar Pradesh.

There’s a consistent pattern across states of illiterate women and those with no formal education having lower fertility rates than those with below primary level education. It raises the question: does little education lead to higher TFR? Is a threshold number of years of education required to reduce fertility? Experts say this pattern – referred to as “inverted-J” — has been observed in other countries. However, they caution that this pattern in 2017 data, and to some extent in 2016 data, can’t be taken as significant unless it stays for 4-5 years.

‘State culture has greater influence than education’

The pattern tends to be more pronounced in highfertility populations, say experts. However, in the 2017 data, this pattern held true even in states with lower fertility. For instance, in Bihar, a high fertility state, the TFR of women who have not completed primary schooling is 4.4 compared to 3.7 for illiterate women. Similarly, in Odisha with an overall low fertility rate of just 1.9, the TFR of illiterate women was 2 compared to a TFR of 3.6-3.5 among those with primary level schooling or below. At the all-India level, the TFR for women with below primary education was 3.1 compared to 2.9 for illiterate women and 2.4 for those without formal education.

Dr KS James, director of the International Institute for Population Studies in Mumbai, explained that this inverted-J pattern in fertility is seen not only in education levels but also in income levels. “Usually there is an inverse relationship between education or income and fertility, but it has been observed that fertility could go up with a slight increase in education or income level. But eventually, fertility declines with higher levels of education,” said Dr James. However, Prof PM Kulkarni, a renowned demographer and population expert, pointed out that the pattern was clearly discernible only in the 2017 data. “It could be because the number of illiterates in all states has been falling and so the sample size for illiterates might be small, leading to errors. At this stage, I wouldn’t call it a trend. We need to see it for three or four years,” said Prof Kulkarni.

Dr James pointed out that the culture of a state or geography had greater influence than education or socio-economic characteristics on fertility while explaining why even urban graduates in high-fertility states like UP or Chhattisgarh had fertility rates of 2.2 and 2 respectively compared to illiterate rural women in states like Maharashtra and West Bengal with fertility rates of 1.3 and 1.4 respectively.

2005-17: saturation point reached?

July 5, 2019: The Times of India

From: July 5, 2019: The Times of India

With India set for a sharp slowdown in population in the next two decades, the Economic Survey calls for optimising education infrastructure, if necessary by merging schools, as the number of school-going children is estimated to decline by 18.4% between 2021 and 2041.

This will need to be balanced by a increase in health infrastructure with an expanded focus on geriatric care as demand for hospital beds is set to go up in view of the growing healthy life expectancy for both men and women at 60 years of age. As of 2016, population in the 5-14 years agegroup, which roughly corresponds to the number of elementary school-going children, has already begun declining across all major states except Jammu & Kashmir.

Population projections suggest that this trend will continue through 2041 and the size of the 5-14 years population will drop sharply in Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Punjab, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka by 2041. It will also decline in the laggard states such as Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh.

“In light of the projected decline in elementary schoolgoing children, the number of schools per capita will rise significantly in India across all major states even if no more schools are added,” it is stated in the survey report.

It said that states such as Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Andhra Pradesh and MP have more than 40% of elementary schools with fewer than 50 students. Similar trends exist in Chhattisgarh, Assam and Odisha with large number of schools per capita and small school size. “The number of elementary schools with less than 50 students has increased over the past decade across all major states except Delhi,” it is stated. “The time may soon come in many states to consolidate or merge elementary schools in order to keep them viable. Schools located within 1-3 kms radius of each other can be chosen for this purpose to ensure no significant change in access”. The recommendations come with a word of caution that this is not about reducing investment in elementary education, but is an argument for shifting policy emphasis from quantity towards quality and efficiency of education.

While school going population will decline, the ageing population with enhanced life expectancy is going to put pressure on the health infrastructure. It is pointed that if India’s hospital facilities remain at current levels, rising population over the next two decades will sharply reduce the per capita availability of hospital beds in India across all major states. For states in the advanced stage of demographic transition, however, the rapidly changing age structure will mean that the type of health care services will have to adapt towards greater provision of geriatric care.

2012-17: Both sex ratio, fertility rate decline

Rema Nagarajan, July 16, 2019: The Times of India

i) Sex ratio

ii) Fertility rate

From: Rema Nagarajan, July 16, 2019: The Times of India

India’s sex ratio at birth (SRB) — the number of female babies born for every 1,000 male babies — fell to an all-time low of 896 in 2015-2017. This would translate into approximately 117 lakh girls missing in the country in a span of three years. Five large states — Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Bihar, Maharashtra and Gujarat — with poor sex ratios at birth account for about two thirds of these missing girls.

Uttar Pradesh alone accounts for about 34.5 lakh missing girls or about 30% of the total, followed by Rajasthan with 14 lakh, Bihar with about 11.6 lakh and Maharashtra and Gujarat, each with about 10 lakh girls missing in the three years.

While the sex ratio continues to decline despite government efforts, India’s total fertility rate — the number of kids likely to be born to a woman — which was stuck at 2.3 from 2013 onwards, fell to 2.2 in 2017, close to the replacement level fertility of 2.1.

Replacement fertility is the level at which a population can replace itself from one generation to the next without growing or declining and it is estimated at 2.1 children per woman. Below this level, the population starts shrinking. Nine states, including some of the least developed, have fertility levels higher than 2.1, though two of these, Gujarat and Haryana, are at 2.2. Only in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar are women on average likely to have three or more children.

Of 13 states with below replacement level fertility, Delhi has the lowest at 1.5. Barring Rajasthan, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, urban populations of all states have less than replacement level fertility. In rural areas, MP, UP and Bihar have a fertility rate of three or more. India’s total fertility rate has fallen steadily from 3.2 in 1998 with the most dramatic improvement in the southern states where it fell from about 4 in the 1970s to the current level of 1.6 or 1.7.

The pressure to have smaller families in a society that prefers boys, along with access to sex determination methods and methods of getting rid of female babies could be leading to an alarmingly skewed sex ratio. Though some of the states with the worst SRB, such as Haryana, Gujarat and Punjab, have shown gradual improvement over the years, they are yet to regain the levels of the 1990s. Also, these are mostly states with smaller populations and fewer births. So, the improvement here is more than offset by declining SRB in populous states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh with a huge number of births, leading to India’s overall SRB continuing to fall.

Moreover, many states that had earlier recorded high SRBs such as Kerala and Odisha have witnessed a steep decline. Kerala had an SRB of 948, second only to Chhattisgarh, but this has plummeted 26 points from 974 in 2012-14. In Odisha, the fall from 956 in 2011-13 to 929 by 2015-2017 is an even sharper 27 points.

2019-21: 2.0

Nov 26, 2021: The Times of India

From: Nov 26, 2021: The Times of India

From: Nov 26, 2021: The Times of India

From: Nov 26, 2021: The Times of India

From: Nov 26, 2021: The Times of India

From: Nov 26, 2021: The Times of India

From: Nov 26, 2021: The Times of India

Population control has been an official government policy ever since India launched its family planning programme in 1952. The issue was placed on the national frontburner two years ago when Prime Minister Narendra Modi brought it up in his Independence Day speech. “There is one issue I want to highlight today: population explosion,” he had said in 2019. Population explosion will cause many problems for our future generations, he added and also that “those who follow the policy of small family also contribute to the development of the nation, it is also a form of patriotism”. Data released this week shows that Indians are already on the path to becoming more ‘patriotic’ and the population time bomb may have been defused.

The total fertility rate (TFR) or the average number of children born to a woman over her lifetime determines the population growth. At TFR of 2.1, the population gets stabilised, and just replaces itself from one generation to the next. India’s TFR has dropped below replacement level for the first time ever and is now 2, shows the latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data for 2019-21. India’s TFR had dropped from 2.7 in 2005-06 to 2.2 in 2015-16.

The National Population Policy formulated in the year 2000 has been aiming for a TFR of 2.1. The fall in the national TFR to 2 means India has achieved its goal of population stabilisation too and it need not worry about an ‘explosion’ anymore. However, there are wide variations within the country when it comes to population growth. The fertility rate of 1.6 in urban areas, for instance, is much lower than 2.1 in rural India. Then there are variations across states. There are now just five states, Bihar (3), Meghalaya (2.9), Uttar Pradesh (2.4), Jharkhand (2.3) and Manipur (2.2) with a TFR above replacement level. Two states have TFR at the same level as the national average: Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan. The lowest fertility rate among larger states is in Jammu and Kashmir at 1.4. The TFR in all states has improved in the last five years.

Barring Bihar, urban TFR in all states is below replacement level. Even rural TFR is above replacement level only for Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Jharkhand among the larger states and for Meghalaya, Manipur and Mizoram among the smaller states.

Some of the most populous states such as Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar have shown significant decline in TFR, which has helped India’s overall rate fall below the replacement level. Among larger states, Kerala and Punjab had the lowest fertility rate of 1.6 in NFHS-4, followed by Tamil Nadu with 1.7. However, while Punjab’s fertility rate has remained the same, Kerala and Tamil Nadu are the only states in India where fertility rate went up, though marginally, to 1.8 in the 2019-21 survey.

What makes the talk of population and population control politically problematic in India is the religious polarisation around it. Muslims, the largest religious minority group in the country, have often been at the receiving end of political barbs. The rise in the share of Muslims in India's population from 9.8% in 1951 to 14.2% in 2011 has been pointed as a trend that could threaten the majority status of Hindus. However, the fertility rate numbers point to a different trend. The reduction in fertility among Muslims has been much sharper than that seen among Hindus. This means Muslims are adopting family planning at a faster rate than Hindus after a late start. Of the nine states, for which NFHS-5 data was released earlier, the TFR is above replacement level in the Muslim community in just two states, Kerala (2.3) and Bihar (3.6).

But where do we stand globally? According to World Bank data, the highest fertility rate is in Niger (6.8) and Somalia (6). Among the neighbouring countries, Nepal has the lowest fertility of 1.9 followed by India and Bangladesh (2), with Sri Lanka (2.2) and Pakistan (3.5) still above replacement levels. At the state level, Sikkim has the lowest fertility rate of 1.1. This is equivalent to the lowest fertility rate in the world of 1.1 in South Korea.

Bottomline: India’s population growth will slow down and ultimately decline but it will take a couple of years for that since the future mothers are already born. Some of this fall in fertility rate will be neutralised by the rise in life expectancy. India may still become the most populous country in the world (the United Nations forecasts that India's population will peak around 1.6 to 1.8 billion from 2040-2050) but the pace to the top of the list will be slower. For states, it means many won’t need to penalise families with more than two children, as some like UP and Assam plan to do. The bad news is that as the TFR falls, the young population and the future labour force will also contract. A higher GDP growth depends on the labour force participation and its productivity. A shrinking workforce will put the focus on tech and innovation for future economic growth. An ageing population means its increasing dependence on the younger, working-age population too.

2021: Kerala sees decade’s worst live births dip

Aswin J Kumar, January 5, 2022: The Times of India

THIRUVANANTHAPURAM: Live births in Kerala recorded the highest drop in a decade in 2021, showed civil registration figures given by the local self-government department. The number of live births dipped by 71,000 between 2020 and 2021, and for the first time in the past decade, the state's live births went below four lakh.

Ernakulam was the lone exception among the districts. While live births decreased by 1,000 to 16,000 in other districts, in Ernakulam it increased from 26,190 in 2020 to 27,751 in 2021. The steepest drop was evident in Malappuram, Kannur and Kozhikode, which recorded a decline of 18%, 22% and 26%, respectively. Districts like Trivandrum, Kollam and Thrissur recorded a decline of 5,000 to 6,000. Over the past 10 years in Kerala, live birth rate has shown marginal variations between years. Officials involved in registration of vital events said delayed registration could not be taken into account while calculating live births in the state.

"In Kerala, kiosk-based registration system for institutional delivery ensures one of the highest percentage of birth registrations in India and that too within the prescribed time period of 21 days," said chief registrar of births and deaths Thresiamma Antony.

Officials with reproductive child health at the National Health Mission and obstetricians said that Covid-19 was a major factor in bringing down the overall number of births.

Government policies to control population growth

Two-child policy

The Times of India July 2021 and [1]

Which states have a two-child policy?

[As in 2021 July] two BJP-ruled states, Assam and Karnataka are moving towards implementing a two-child policy.

12 states have already experimented with some form of a two-child policy, but limited to those running for elected government posts or government jobs. These are Odisha (1993), Haryana (1994), Andhra Pradesh (1994), Rajasthan (1994), Himachal Pradesh (2000), Madhya Pradesh (2000), Chhattisgarh (2000), Uttarakhand (2002), Maharashtra (2003), Gujarat (2005), Bihar (2007) and Assam (2017).

Of these, four states, namely Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Haryana, have revoked the norms. .

Mother’s education and fertility rates

2001-2011

The Times of India, May 03 2016

Well-educated moms have half the no. of kids that illiterates do: Census data

Subodh Varma With more girls reaching higher levels of education, the average number of children born to them after they get married is falling, Census 2011 data released on Friday shows. India had nearly 340 million married women and the average number of children was 3.3, down from 3.8 in 2001 and 4.3 in 1991.

But hidden in this average figure is a wide range between an illiterate mother and a welleducated one. Mothers who were deprived of education in their early life and have remained illiterate had 3.8 children on average. At the other extreme, mothers with a graduate degree or above had just 1.9 children. That's half the number of children compared to illiterate mothers.

The average number of children is calculated by counting the number of children ever born to women in the 45-49 age group, which is the end of their reproductive age and thus represents the total children they can have.

While the spread of education is widening with each passing year, school drop out rates are still unconscionably high among girls. An idea of this is gained from enrolment data for 2014-15 put out under the District Information System for Education (DISE), which shows that there were around 13 million girls enrolled in Class 1 but the number went down by 58% to 5.4 million in Class 12. With this kind of massive dropout, it will take many years for the overall fertility rates to decline substantially more. Census data shows that between the two ex tremes of illiterate and graduate+ mothers, there is a continuum as the educational level increases, the average number of children goes down. Mothers who have not studied beyond class 8 (middle school) have three children on an average, those who dropped out between middle and high school had 2.8 children and those who had studied between class 10 and graduation restricted their children to 2.3.

The rates of decline between 1991 and 2001 were 14% for mothers who studied up to middle school but between 2001 and 2011 this decline was more at 18%. It was a similar situation for other educational levels.

Is it just education of mothers that is causing this decline? Experts say that it is a key factor but accompanied by a set of other circum stances that go with mothers' education. More educated women are likely to be from better income households and are also likely to be married to more educated men.So, according to them everything put together is helping.

The Census data also shows that there are still nearly 96 million illiterate married women who are in the child bearing age, that is, 15-49 years. And there also are about 16 million married women in the same age group that have not studied beyond primary level. Presumably, they are yet untouched by the wider trend of having less children.