Mumbai: Bombay High Court

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A brief history

By Iqbal Chagla, Sep 20, 2019: Mumbai Mirror

The writer is a Senior Advocate and a former president of the Bombay Bar Association

From: By Iqbal Chagla, Sep 20, 2019: Mumbai Mirror

From: By Iqbal Chagla, Sep 20, 2019: Mumbai Mirror

From: By Iqbal Chagla, Sep 20, 2019: Mumbai Mirror

From: By Iqbal Chagla, Sep 20, 2019: Mumbai Mirror

MumbaiMirrored: The king of courts

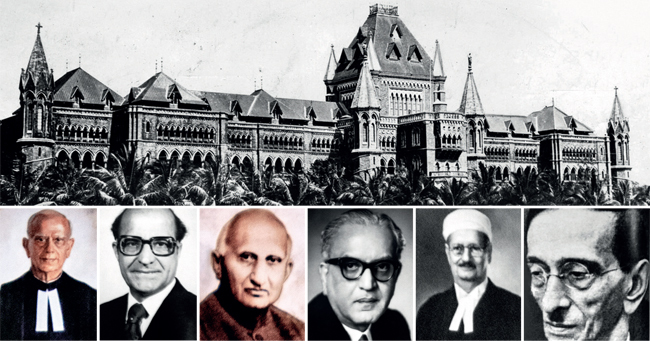

The grandeur of the Bombay High Court lies not just in its magnificent edifice – it has been the home of historic trials and brave legal luminaries.

The High Court of Judicature at Bombay (and that is how it continues to be called) was established on June 26, 1862 by Letters Patent issued by Queen Victoria and was formally inaugurated on August 16, 1862, quietly and without fanfare.

The High Court functioned in a building on Apollo Street (that later became the Great Western Hotel) awaiting its present site. It was Colonel John Augustus Fuller who, it is said, conceived the design from a sketch of one of the castles that he drew on a trip down the River Rhine.

The building found place in the large open space that became available in the Esplanade and where it has remained ever since, a majestic edifice that proclaims the majesty of the law.

It took seven years to complete at a cost of Rs 16,44,528 - Rs 2,668 less than the sanctioned amount. It was built to house 15 judges, although it had no more than seven until 1918. Today, the sanctioned strength is 94 judges, of which 67 have been appointed, distributed between the parent court and the benches in Nagpur, Aurangabad, and Goa.

Shortage of space has led to a movement to shift the high court to a building to be constructed in Bandra Kurla Complex which, if and when it takes place, would be a great tragedy, a move from this magnificent Neo-Gothic structure to a modern PWD-designed building.

The Bombay High Court has often been described as the premiere High Court in the country. The Bench and the Bar both contribute to the administration of justice and the Court has had the privilege of having outstanding judges and brilliant lawyers. The tone for judicial independence from the executive was truly set by Sir John Peter Grant whose enormous portrait (the largest in the Court) adorns a wall in the Central Court. He was a judge of the Supreme Court (the precursor to the High Court) when a writ of habeas corpus issued by his Court was refused to be obeyed by the executive. Worse, the Governor of Bombay, issued instructions that no writ of the Court issued in respect of any person outside the island city should be obeyed. John Peter Grant, as a reaction to the contempt shown by the executive to the writs issued by the Court, locked up the Court and sailed for England - in fact, the Court remained closed for five months. Cast in the same mould, not merely fiercely independent but brilliant and outstanding were other pre-Independence judges who established the high traditions of the Bombay High Court. They were, among others, Justices Lawrence Jenkins, John Jardine, Kashinath Telang, M G Ranade, Badruddin Tayabji and John Beaumont, to name but a few.

When at the dawn of independence, M C Chagla was appointed the first Indian Chief Justice of the Bombay High Court, he wondered (as he recounted in Roses in December) whether he would be able to maintain the very high traditions of one of the premier high courts in the country. He need not have wondered. H M Seervai, the great constitutional lawyer, said that “in his experience he had known no other Court like his”. There was, he said, “complete confidence that in his Court every nerve would be strained to see that that right was not worsted and wrong did not triumph.” Nani Palkhivala said that Chagla’s was the Golden Age of the Bombay High Court where he “illumined justice and humanized the law”. Outside the Court where Chagla presided, in Palkhivala’s words, for “eleven priceless and luminous years”, there is a bas-relief statue (the only statue within the building) with the inscription “A great judge, a great citizen, and above all, a great human being.”

Outside the Central Court (that earlier served as the Sessions Court) there is a marble tablet with the words “Inspite of the verdict of the jury I maintain that I am innocent. There are higher powers that rule the destiny of men and nations and it may be the will of providence that the cause which I represent may prosper more by my suffering than by my remaining free.” These were the words Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak spoke in 1908 on his conviction for sedition in the Central Court. Tilak was charged and found guilty of sedition for articles he wrote in his publication Kesari. Justice Dinshaw Davar had described Tilak as a man with “a diseased and perverted mind” and imposed a savage sentence of six years “transportation” (i.e. confinement in the Andaman Islands). The tablet was unveiled by Chief Justice Chagla, as he said, to “atone for the misdeeds of previous generations.”

The true worth of a court is determined at times of grave adversity. There could have been no greater gloom and despair than during the dismal, seemingly hopeless, dark days of the Emergency and it was here that the Court boldly proclaimed in resounding tones its courage and independence.

M P Nathwani (a former judge of the Court) had convened a meeting at Jinnah Hall where M C Chagla and J C Shah were among the speakers. The Police Commissioner denied permission.

Nathwani filed a petition challenging the order and Nani Palkhivala together with 144 lawyers appeared for him. Nani, in a brilliant and memorable address, said everything within the four corners of the Court that could not be uttered outside.

In a resounding judgment, Chief Justice Kantawalla and Justice Tulzapulkar set aside the order. In words that resonated and were a breath of fresh air, they castigated the Police Commissioner who, they said, was more loyal than the king. Again, when the Censor passed an order of pre-censorship, a Bench of Justices D P Madon and M H Kania castigated the Chief Censor and in setting aside the order observed “under the Censorship Order the Censor is appointed to be the nursemaid of democracy not its gravedigger”.

During the Emergency, the Court entertained numerous petitions challenging orders of detention and rejected the arguments of the government that Article 21, the right to life, stood suspended during the Emergency. A view, unfortunately, not shared by the Supreme Court in A.D.M. Jabalpur which, mercifully, now stands overruled.

But judges can only be as strong and independent as the lawyers who appear before them. The administration of justice is, after all, a combined effort between the Bench and the Bar.

Before Independence, a galaxy of talent was evident: at the top of the heap were Inverarity and Bhulabhai Desai and not far behind them Chimanlal Setalvad, Jamshedji Kanga, M A Jinnah, Phirozshah Mehta, H C Coyajee, K M Munshi, and V J Taraporevala to mention a few. And post Independence, again to name only a few, the stalwarts were Motilal Setalvad, C K Daphtary, H M Seervai, Nani Palkhivala and Ram Jethmalani.

An example of the sturdy independence of the Bar was evident when a resolution was moved by Servulus Baptista, a member of the Bombay Bar Association to honour Jinnah on his attaining 50 years at the Bar - this was in March 1947. The resolution was highly controversial and stood deferred on more than one occasion. It was finally put to vote and was carried 37 in favour and 35 against, those in favour asserting that Jinnah’s politics, distasteful as they may be, were irrelevant in honouring a member of the Bar.

In 1990 the Mumbai Bar moved resolutions against five judges of the Court impugning their integrity and calling for their resignation. One judge resigned before the resolution, two were transferred to other courts, and two were given no further judicial work. And five years later, a resolution calling for the resignation of a sitting Chief Justice of the court on grounds of corruption was passed whereupon the Chief Justice resigned.

Is it any surprise, then, that the Bombay High Court has given 30 judges to the Supreme Court of whom 9 rose to be Chief Justices of India, or that the Bar has given to the country 6 Attorney Generals of India?