Mob violence/ lynchings: India

(→Incidents) |

|||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

[[Category:India |M ]] | [[Category:India |M ]] | ||

[[Category:Crime |M ]] | [[Category:Crime |M ]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Law,Constitution,Judiciary |M ]] | ||

=Incidents= | =Incidents= | ||

Revision as of 16:12, 18 June 2018

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Incidents

2014-June 2017

Jun 27 2017: The Times of India

A spurt in lynching cases has exposed the absence of law enforcement to punish the guilty. The only known instance of conviction in a mob justice case in recent years was of ex-MP Anand Mohan and two MLAs who got life in 2007 for lynching of Gopalganj DM Krishnaiah in 1994.

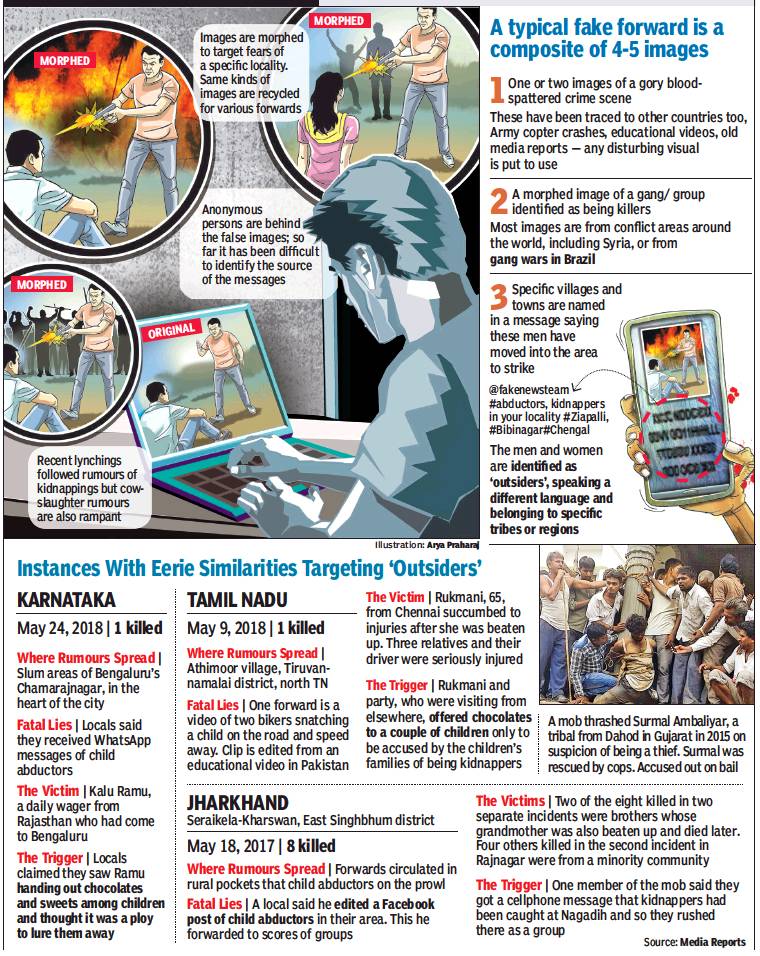

2017-18: How fake forwards create killer mobs

June 18, 2018: The Times of India

From: June 18, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

2017-18: How fake forwards create killer mobs

Doctored content, fake alerts and sensationalised messages are all it takes to fuel mass suspicion of strangers and propel mobs to brutally attack innocents. These forwards, of blood-thirsty gangs of kidnappers, thieves or dacoits, spread mainly via WhatsApp and Facebook, use morphed images, even from other countries, to create a fear psychosis

2018

Why hoaxes behind lynchings beat cops, June 18, 2018: The Times of India

Reporting by Petlee Peter in Bengaluru, Mahesh Buddi in Hyderabad, Debabrata Mohapatra in Bhubaneswar, B Sridhar in Jamshedpur, Mohammed Akhef in Aurangabad, Shanmugha Sundaram J in Vellore

A slew of protests took place across the country after 10 people were killed in two months by mobs reacting to rumours of kidnappers grabbing children, but the flow of fake messages and morphed videos has hardly been impacted. Though police round up people, sometimes in the hundreds, the fight against fake messages stoking real fears is barely begun.

The Bengaluru police is no stranger to countering fake messages warning of kidnappers or terror plots. Every day, a team of 14 officers monitors Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and WhatsApp. Tracking has worked at times — during the Cauvery riots a few years ago, social media was used to counter rumours.

But their efforts couldn’t save a 26-year-old from Rajasthan last month in the heart of Bengaluru. Kalu Ram was beaten to death by locals who fell prey to WhatsApp messages about abductors. In fact, 90 people were assaulted by mobs over child-abduction rumours in April and May in Karnataka.

An officer says there’s no way to trace the origin of such messages on WhatsApp. Instead, they go person to person, finding out who forwarded it. “We counter such messages with our own on our WhatsApp groups,” said the officer. An early instances of WhatsApp rumours spiralling out of control was in Bengaluru in 2012 when fear of attacks led to an exodus of north-easterners.

“We can only ask people to refrain from believing rumours,” says Odisha DGP Rajendra Prasad Sharma. About 25 people, mostly labourers or beggars from neighbouring states, have been attacked across Odisha in the last two months on suspicion of being kidnappers. There were no deaths but police are trying to prevent attacks, counter rumours, says Sharma.

There seems to be only so much the police believes it can do to stop the rumours. In Maharashtra’s Aurangabad, staff have been asked to join as many WhatsApp groups as possible to track fake messages and also undertake patrolling to alert residents. Further, pollice decided to block for a period internet services for seven hours daily in the rural areas to curb the spread of rumours.

Awareness campaigns are on in Telangana, where three people were lynched in separate incidents in May on suspicion of being kidnappers from Bihar and UP. Hyderabad cybercrime cops arrested a private employee for spreading rumours via WhatsApp while 14 people in the city were heldlast month for attacks on transgenders over rumours of cross-dressing kidnappers.

Since April 22, at least five have been killed in similar rumour-based lynchings in Tamil Nadu’s northern districts. Vellore SP P Pakalavan told TOI that rumour-mongers would be booked under the Goondas Act.

Mass arrests and booking the accused under multiple sections are how police tackle mob violence. Police arrested 11, and booked 400 villagers for murder, attempt to murder and assault in Aurangabad, where two tribals were lynched and six injured in May. Many of the fake messages are forwarded in areas where abduction is a very real fear among locals. “The rumours were around for a month,” said a policeman in Aurangabad’s Vaijapur, adding that alarmed locals were staying up on night vigils bearing torches and sticks. But the police, though in the know about the messages, could do little to prevent the murderous attack on the two tribal men.

In Jharkhand, more than 100 people have been accused in three lynching cases in which 10 innocent people were killed over 10 days in May 2017 in East Singhbhum and adjoining Seraikela-Kharswan districts. All three cases are at various stages of trial. After the lynchings over the last two months, East Singhbhum police have launched a fresh drive to counter rumours. “We’ve appealed to people to inform police if they see such rumours on social media,” said a DSP in Jharkhand.

Legal position

How are lynch mobs punished?

There is no single ‘special’ law to bring those accused of lynching incidents to book. Lynching is so unique a category of crime that it is a cumbersome process for police and the courts as well. When a mob renders kangaroo justice, it is almost impossible to identify the members and fasten culpability individually for the purpose of a fair trial.

In the absence of a special law, how are lynch mobs punished?

Jurists say police must assemble a bouquet of charges to hold the case together. Lynching being no ordinary murder (Sec 302), police must also invoke other criminal charges such as common intention (Sec 34) and being present and abetting an offence punishable with death (Sec 114).

“While murder, read with common intention and abetment, forms the bedrock, police can invoke conspiracy charges against those who orchestrated the lynching or invoke IT Act 66A against those who created the content and spread it on social media,” said former additional solicitor-general of India P Wilson.

Hence, for a watertight lynching case, there must be at least five criminal elements woven into it.

Former special public prosecutor for Tamil Nadu’s human rights court V Kannadasan says leaving out the ‘conspiracy’ portion helps the prosecution, since they need not piece together every evidence to prove that there indeed was a meeting of minds that led to the mob being formed followed by the murder. Most lynchings are not premeditated.

The charge of common intention, on the contrary, treats whoever commits the crime on a par with those standing guard. “Mere presence of an accused at the place of occurrence is enough to convict him. Police need not prove with evidence individual roles played by each mobster. Any number can be included,” he said, adding that such an approach works effectively in cases of lynching.

To show conspiracy (Sec 120B), a meeting of minds has to be proved, and visual evidence is a must to prove involvement of offenders. For common intent, video evidence plays a crucial role, as police can follow procedure to conclusively prove that the offender was present at the scene of occurrence. They only need the video clipping or photograph certified under the Evidence Act, vouchsafing that the video/photo was taken by X and downloaded by X.

Tamil Nadu witnessed five lynchings in the past two months. The genesis was WhatsApp forwards warning villagers that a group of ‘child lifters’ had descended on their areas and that scores of kids had already gone missing. Such was the ire evoked by the rumour that a mob in Pulicat near Chennai gouged out a stranger’s eyes and hanged him from a bridge.

The same rumour claimed lives of two in Assam within a month.In the police net now are those who forwarded the messages and who are seen in video clippings kicking and punching the Pulicat victim. “Though those handling platforms like WhatsApp have a responsibility, they cannot be treated on a par with the actual attackers,” believes advocate and deputy editor-in-chief of Madras Law Journal V Lakshminarayanan. “Fact remains though that had he not forwarded the rumour, the tragedy would not have occurred at all. To that extent, he, too, contributes to the tragic crime.”

See also

Mob violence/ lynchings: India