Malnutrition in South Asia

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Hunger back to 1990 levels in South Asia: UN report

India Could Miss Meeting Millennium Development Goals

Himanshi Dhawan

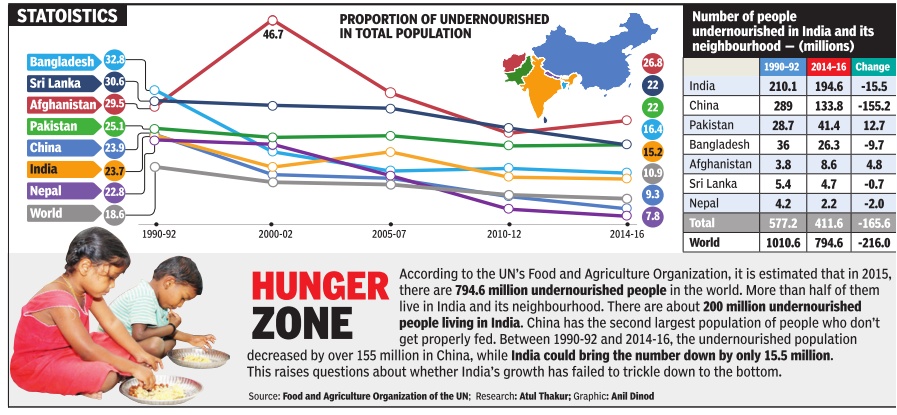

New Delhi: Even before the food and financial crises hit the world, prevalence of hunger in South Asia was increasing instead of decreasing, taking the region further away from the goal of reducing hunger by half by 2015, according to the United Nations Millennium Development Goals report, 2010.

The report says in 2005-2007, the proportion of undernourished people in South Asia had swelled to levels last seen in 1990. The prevalence of hunger had increased from 20% in 2000-2002 to 21% in 2005-2007. The regional average was 21% in 1990-92, indicating that no progress had been made in the last two decades in reducing hunger levels and that India — the dominant country in the region — will not be able to meet its millennium development goals.

The situation has only worsened since 2007. According to UN figures, the employment to population ratio in South Asia fell to 56% in 2008 from 57% in 1998. The 2009 estimates put it even lower at 55%. An International Labour Organization report says more people got into vulnerable jobs in 2009 due to the financial meltdown. The proportion of employed people living under $1.25 a day jumped sharply from 44% in 2008 to 51% in 2009.

The UN’s latest millennium development goals report — to be released on Wednesday — says that aggregate food availability globally was relatively good in 2008 and 2009 but higher food prices and reduced employment and incomes meant that the poor had less access to that food.

Food prices spiked in 2008 and falling income due to the financial crisis further worsened the situation. UN’s Food and Agricultural Organization estimates that globally, the number of people who were undernourished in 2008 could have been as high as 915 million and exceeded one billion in 2009.

Ironically, before the onset of the global crisis, a number of regions were well on their way to halving the proportion of their undernourished population by 2015. The prevalence of hunger also declined in Sub-Saharan Africa although not at a pace that was sufficiently fast to compensate for population growth and to put the region on track to meet the MDG target.

In East Asia, after a striking drop in the prevalence of hunger in the 1990s, the rate of malnourishment has stalled at 10% between 2000 and 2007. Southeast Asia, which was already close to the target of cutting the hunger rate in half against 1990 levels, made additional progress, but not as rapid as its rate of poverty reduction.

Malnutrition in India

`2.3cr children in India malnourished'

Subodh.varma@timesgroup.com

The Times of India Aug 04 2014

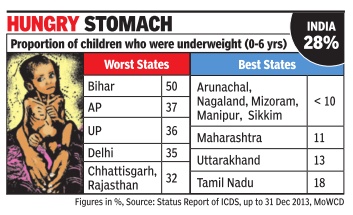

Bihar Has Dubious Distinction Of Having Highest Percentage Of Under-Weight Kids: ICDS

About 2.3 crore children in India, up to 6 years of age, are suffering from malnourishment and are under-weight, according to a status report on the anganwadi (day care center) programme, officially known as ICDS. This staggering number amounts to over 28% of the 8 crore children who attend anganwadis across India.

The status report includes state-wise data for underweight children. In Bihar, the proportion of under-weight children is nearly 50%. Andhra Pradesh (37%), Uttar Pradesh (36%), Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh (both 32%) are some of the other large states with a high proportion of children being malnourished.

Delhi reported that a shockingly high 35% of the nearly 7 lakh children who attend anganwadis were un derweight. This shows that the extent of poverty and malnutrition amongst the urban poor is comparable to rural areas despite all the advantages the cities offer.

In all the northeastern states except Assam, Tripura and Meghalaya, less than 10% of children were underweight children. Other large states with a comparatively low rate of malnutrition are Maharashtra (11%) and Tamil Nadu (18%).

There has been no comprehensive survey of children's malnutrition in India since the last National Family and Health Survey in 2005-06. That had estimated 46% of children in the 0-3 years age group as underweight after surveying a sample of about 1 lakh households across the country . The data from anganwadis pro vides a snapshot drawing upon a much larger base.

There were an estimated 16 crore children of ages up to 6 years in the country , as per the 2011 Census. Of these, about half seem to be attending the anganwadis going by the records of the programme. Most of those attending anganwadis belong to poorer sections. But large sections do not get access to it. A 2011 Planning Commission evaluation had said that there is a shortfall of at least 30% in coverage.

There are over 13 lakh anganwadis which look after the kids and provide `supplementary nutrition' to them. As part of their duties, personnel at each anganwadi weigh the attending kids every month and keep a record.

TOI contacted anganwadi workers from several states to confirm the weighing procedures. Till recently, two weighing instruments were provided for each anganwadi center -one pan-type weighing machine for smaller babies and another hanging instrument with a hook at the bottom on which the child is hooked up through a belt or a garment.

In some states, like Delhi, there were cases where the hanging type machine was not in working condition and hence only children up to three years of age could be weighed. In Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha and Kerala, workers said that they were weighing children up to 6 years.

Why is it that children's weight is not improving despite getting nutritional supplements at the anganwadis?

In many states, the quality of food given to children is very bad and they may not be eating it, according to AR Sindhu of the Anganwadi Workers' Federation. “Often this is the case where food provision service is outsourced to NGOs,“ she said.

UNICEF, 2009: Uttar Pradesh: "Riskiest state"

From the archives of “India Today”, January 29, 2009

Farzand Ahmed

It’s a human tragedy of massive proportions that everyone seems aware of but is clueless about combating. In Uttar Pradesh, the country’s most populous state and the only one currently to be run by a woman, women run the highest risk of maternal mortality. UNICEF has called the state, the “riskiest state” for babies, especially newborns and mothers. In its ‘State of the World’s Children 2009’ report, it has also termed the state “the riskiest place for a woman to have a baby in India. In Uttar Pradesh, a woman has a one in 42 lifetime risk of maternal death, compared to a probability of just one in 500 for women in Kerala”. Only a week before UNICEF presented its report to Governor T.V. Rajeswar, Vice-President Hamid Ansari had curtly remarked at a function in Lucknow that “being born in Uttar Pradesh reduces one’s lifespan by several years. It would seem that the state you are born into determines how long you would live”. Quoting data produced by the National Family Health Survey 2005-06, the vice-president said: “Indeed the picture that has emerged is very distressing.” The UNICEF report highlights the link between maternal and neo-natal survival, and suggests opportunities to close the gap between rich and poor countries. This is not the first report to paint a gloomy picture. Six months ago, the state Planning Department had brought out a firstever report titled ‘The State of Children in Uttar Pradesh’. That too made for depressing reading. The study, jointly conducted with UNICEF, revealed that 52 per cent of the state’s children were severely malnourished while the all-India figure was 43. It also revealed that while the percentage of malnutrition among children was just 35 in the least developing world, the figure for sub-Saharan Africa was 28 per cent. South Asia as whole has a 42 per cent child malnutrition rate as against 26 per cent in developing countries. Several other children in Dhannipur village in Varanasi await a similar fate. Suffering from malnutrition, most of them are children of weavers whose looms once churned out saris. Now out of work, they’re unable to provide their children with proper meals. But Dhannipur is perhaps just a microcosm of the entire state. Peoples’ Vigilance Committee on Human Rights (PVCHR) quotes a state government survey to say that 540 children are still suffering from Grade III and Grade IV malnutrition. Last year, Bijo Francis of the Hong Kong-based Asian Human Rights Commission circulated a report worldwide saying, “When he (Sahabuddin) died, he weighed six kg. This is Grade III malnutrition (often categorised as severe), a condition that exists in places like Somalia.” Malnutrition is associated with half of the total number of child deaths and Uttar Pradesh accounts for over 10 million of India’s 72 million malnourished children. Besides this, it is learnt that nearly 40 per cent of primary school dropouts have been denied mid-day meals provided by the government and other voluntary agencies. The state Government has some tough paradoxes to deal with. Despite its 40-million-tonne foodgrain production, over 30 per cent of the state’s 17-crore population barely manage to get a single meal in a day. According to the Planning Commission’s ‘UP Development Report’, even though the state is the largest producer of foodgrain, the per capita production is lower than other states. It’s not just the numbers that are scary. Dr M.Z. Idris, head of the department, community medicine, King George Medical College, Lucknow, adds, “Malnutrition stops total growth of the child, affecting the economic growth of the state or the country.” But these are not the only issues. The state accounts for the highest number of child abuse and child labour cases besides widespread Japanese Encephalitis (JE), mainly in Purvanchal. JE has turned out to be the biggest killer of children every year. Last year, over 467 children died and 2,226 were admitted in Gorakhpur Medical College due to JE. Yet the Government’s concerns are not reflected in its actions. When JE sowed panic in the state, the state Government decided to transfer all its JE specialists. Dr Sanjay Srivastava, one of the founders of Action for Peace, Prosperity and Liberty, says he was taken aback because a court order mentions retaining JE specialists. Clearly, Uttar Pradesh has turned into a land of threatened children. The UNICEF report should ideally be a wakeup call for the state Government.

2013: under-five deaths in India, Pakistan

Mar 29 2015

Sushmi Dey

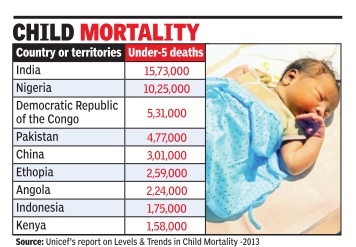

`In 2013, 22% of all under-5 deaths occurred in India'

Malnutrition is biggest killer: NGO

India accounts for most deaths of children aged below five years every year, with 50% of these caused mainly by malnutrition, a new policy paper has said. The paper, released in March and prepared by NGO Forum for Learning and Action with Innovation and Rigour (FLAIR), estimates that 22% of all under-five deaths worldwide occur in India. In 2013, over 15 lakh such children died in India. A Unicef report supports the figure.

According to the Unicef report, about 50% of the world's under-five deaths occur in just five countries: India, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Pakistan and China. Lack of basic sanitation in India is seen as a key factor for the endemic child malnutrition. “(An) Unhygienic environment combined with high population density creates a perfect storm for diseases to thrive, and malnutrition to flourish,“ says Dr Raj Bhandari, adviser-health and nutrition at FLAIR.

According to Bhandari, the absence of sanitation exposes children to infectious diseases such as typhoid and diarrhoea, which rob them of their ability to absorb nutrients and make them vulnerable, causing co-morbidity .

The paper cites Kerala, Manipur, Mizoram and Sikkim to point out that states where 80% or more of the rural population has access to toilets also have the lowest levels of child malnutrition.However, child malnutrition rates are high in states like Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand, where most households are with-out toilets. Apart from poor sanitation, food insecurity, lack of health care and extremely poor conditions of public health are considered major causes of malnutrition.

Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2016

NEW DELHI: India - one of the fastest growing economies in the world - cannot feed its children. This was highlighted once again in the Global Hunger Index (GHI) report released Tuesday which placed the country 97th in a list of 118.

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is a multidimensional statistical tool used to describe the state of countries' hunger situation. It describes India's hunger situation as "serious." On a 0-100 point scale with 100 being the absolute worst in hunger levels, India scored 28.5 - a marginal improvement of a quarter point since the turn of the century. But with the country all set to be the most populaous in the world in the next 10-odd years, the improvement may well reverse.

Hunger and malnourishment is not just a problem for India. Nuclear rival+ Pakistan fares even worse and was placed 107 in the GHI list. The report said 22 per cent of Pakistani population was undernourished and that it scored 33.4 on the 0-100 point scale - a marginal improvement from its score of 35.1 in 2008. On the other end of the rivalry spectrum, China fares tremendously well despite the sheer size of its population. It is placed 20th with a "low hunger level" rating.

Overall, the Central African Republic, Chad, and Zambia fared the worst while Argentina fared the best among the countries included in the study.

Table: South Asia on Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2016

|

Country |

Proportion of undernourished in population (%) |

Prevalence of wasting in children under five years (%) |

Prevalence of stunting in children under five years (%) |

Under five mortality rate (%) |

Score |

|

Afghanistan

|

26.8 |

9.5 |

40.9 |

9.1 |

34.8 |

|

Bangladesh

|

16.4 |

14.3 |

36.4 |

3.8 |

27.1 |

|

Bhutan

|

- |

4.4* |

26.9* |

3.3 |

- |

|

China

|

9.3 |

2.1* |

6.8* |

1.1 |

7.7 |

|

India

|

15.2 |

15.1 |

38.7 |

4.8 |

28.5 |

|

Myanmar

|

14.2 |

7.1* |

31* |

5 |

22 |

|

Nepal

|

7.8 |

11.3 |

37.4 |

3.6 |

21.9 |

|

Pakistan

|

22 |

10.5 |

45 |

8.1 |

33.4 |

|

Sri Lanka

|

22 |

21.4 |

14.7 |

1 |

25.5 |