Kathmandu: What the 2015 earthquake destroyed

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

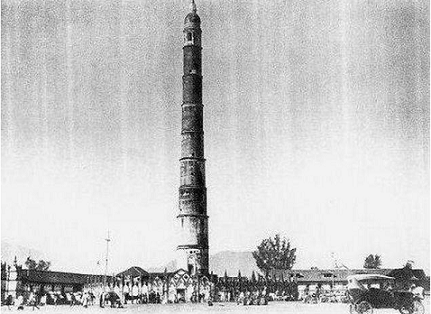

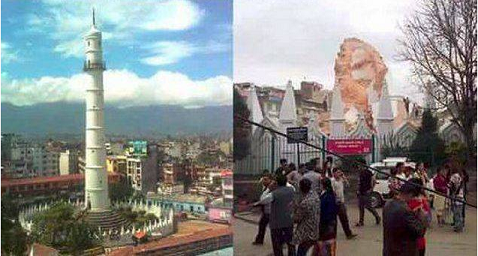

Dharahara tower

Nepal's historic tower

The nine-storey, 50.5-metre-high Dharahara tower was built in the heart of the capital in 1832 by the then prime minister of Nepal Bhimsen Thapa. The tower was white, topped with a bronze minaret and contained a spiral staircase of over 200 steps. It was a major tourist attraction in the heart of the capital. Tourists were charged a small fee to climb the steps to the viewing deck. The architecture of the tower was designed in a fusion of the Mughal and European style. A small statue of Lord Shiva was placed on the top of the tower.

However, on 25 April 2015, the historic tower was reduced to just its base after a powerful earthquake measuring 7.9 on the Richter scale struck Nepal, destroying the minaret and trapping hundreds of weekend visitors under its debris.

A hippie haven ‘becomes merely a memory’

The Glory That Was Hippie-Era Kathmandu Finally Died in the Nepal Earthquake

Charlie Campbell @charliecamp6ell

I’m tired of looking at the TV news/ I’m tired of driving hard and paying dues/ I figure, baby, I’ve got nothing to lose/ I’m tired of being blue/ That’s why I’m going to Kathmandu.

The 1975 Bob Seger classic “Katmandu” immortalized the escapist allure of Kathmandu.

Fabled Kathmandu — that mystical waypoint on the Himalayan hippie trail with its promise of enlightenment and cheap, potent hash — has been devastated.

It was “like the Shire from Lord of the Rings,” says James Giambrone, who moved to Nepal in 1970 after dropping out and leaving his home in New York City. “All the clichés you’ve heard — wonderful people, art abounding, a living museum — I got to experience.”

Those who took their lead from Seger’s jaded protagonist snaked halfway across the globe from London to Bangkok via Istanbul, Tehran and Kabul. They were sandaled beatniks, shunning Western trappings for a life of self-medication and self-reflection, plumes of ganja smoke billowing in their wake.

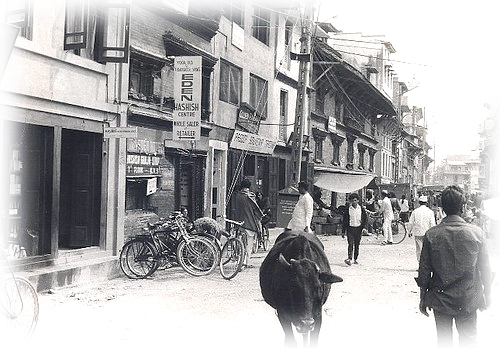

In this heady heyday, cannabis (which continues to grow wild over much of Nepal) was peddled from government-run hash houses. Most pilgrims “were so blasted on temple balls that they couldn’t get their tongues around the word Swayambhunath, so this ancient Buddhist shrine became known in freak-speak as The Monkey Temple,” reminisced Jonathan Gregson for the U.K. newspaper Independent in 2001.

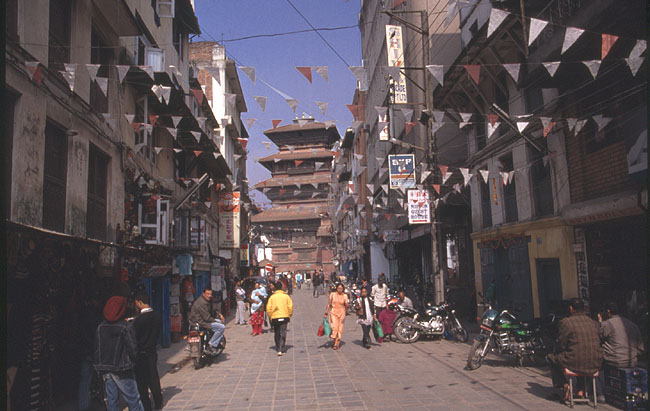

For the same reason, Jhochhen [Tolay] lane, in the old Palast and Temple area by Durbar Square, became known as Freak Street. The hippie contingent liked to congregate on its worn paving slabs, but many of the ancient temples they would have known in the vicinity collapsed in the April 25 quake.

Cannabis was made illegal in the mid-1970s, but its use was tolerated and the hippies kept coming. “The hippies didn’t get arrested for hanging around smoking joints on the temple steps,” Jim Goodman, who spent a decade around the Kathmandu Valley from 1977, [told] TIME. “Smoking was part of Nepali culture and they were pretty lenient about it.”

Goodman, a Ohio native, describes his time in the ancient Newar city of Bhaktapur, just 8 miles (13 km) outside Kathmandu, and where at least 270 people were killed in the most recent quake, as like “living in medieval Europe in the 13th century.”

“I used to wake up around 7 a.m. to the sound of birds at the window, distant temple bells and giggling girls at the water tap by my house,” says Goodman. “I’ve never woken to a nicer sound in my life.”

According to Goodman, who made and sold traditional textiles and wrote books (he has written five about Nepal), there were very few tourists at this time [c.1977-87] and electricity only reached villages just outside the capital by the mid-1980s.

“It was a pretty laid-back place, as you didn’t need much money — I could get by on a dollar or two a day — and it was an interesting city,” he says. “Eight-year-old girls would be carrying around their little brothers on their backs and have the keys to the house while their families worked in the fields.” Those halcyon days began to fade towards the end of the 1980s. The government made visas harder to obtain, and many long-term expatriates, like Goodman, were strong-armed into departing. The Iranian Revolution and civil war in Lebanon made the old overland route to Nepal far more difficult. New arrivals had to come by air, and thus needed deeper pockets. Later, Nepal’s own civil war, which raged from 1996 to 2006, deterred many visitors.

Kathmandu also began to modernize. Large swaths of farmland were converted into sooty industrial estates, with the resultant smog hanging low in the valley, obscuring the once fabulous view of the mountains.

[By 2015], income inequality soared and land values within the Kathmandu ring road rival[led] those of New York City, according to Giambrone, who now runs the city’s Indigo Art Gallery. The flophouses of yore have migrated from Freak Street to the tourist-friendly Thamel region and morphed into high-end hotels, with Berghaus-attired European families replacing wastrels in kaftans and bell-bottoms. While the trickle down of tourist dollars has helped some, particularly the Sherpas, “marginalized groups who are not in the trekking areas do not receive any of the benefits,” says Giambrone.

Modernization was already contributing to the degradation of traditional architecture, with historic houses and gardens being turned into modern concrete buildings. This trend will only accelerate after the quake. Giambrone has been watching with trepidation as bulldozers and cranes lurch through the rubble, damaging fixtures like intricately carved doors and wooden balconies and who knows what hidden artifacts.

“Construction people are moving idols, but why are they moving them? Where are they moving them to?” asks Giambrone. “There is so much around now in the rubble that people can just pick up and carry them off.”

And once all the rubble has been cleared (or looted), there seems almost no chance that the traditional but vulnerable red brick and timber structures will return. The old city will be rebuilt in reinforced concrete and hippie Kathmandu will become merely a memory. The Kathmandu of an even earlier era may not return either.

Destruction of heritage

According to Nepal’s UNESCO chief Christian Manhart, who has just completed a thorough assessment of the city, 60% of all heritage buildings were “badly damaged” in the quake. With them, a whole way of life has finally vanished.

The Kathmandu valley [was home to] some 130 monuments, including several Hindu and Buddhist pilgrimage sites, and seven UNESCO World Heritage sites.

See also

Kathmandu: What the 2015 earthquake destroyed