Judicial delays/ pendency: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Causes

Judicial vacancies

The extent of vacancies has been taken up on the page Judiciary: India

Procedural timeframes, non-adherence to

The Times of India, Aug 25 2016

Brajesh Ranjan

Judgments diluting timeframes in Code of Civil Procedure worsen the problem of adjournments

There are around 21.3 million cases currently pending in various courts in India including the Supreme Court. The magnitude of this pro blem was brought sharply into perspective in a magazine article last year, which stated “if the nation's judges attacked their backlog nonstop with no breaks for eating or sleeping and closed 100 cases every hour, it would take more than 35 years to catch up“. How did we get here? The problem of delay in Indian judicial system has been studied extensively by the Indian Law Commission over the years. In these studies, infrastructural deficiencies have frequently been blamed for the delay . Accordingly , more courts and more judges are seen as a solution.However, a cause that remains underexamined in the literature and public discourse on delay is the contribution of the courts to the problem by nonadherence to procedural timeframes.

Specification of time limits has emerged as a distinctive feature of process reforms across jurisdictions that have been able to quantifiably minimise judicial delay , such as the UK and Singapore. In India, there have been at least two major amendments to the Code of Civil Procedure, in 1999 and 2002, which specified timeframes vis-à-vis completion of various processual steps in civil proceedings. But that doesn't seem to have remedied the problem in any significant way .

Why, one may wonder, have the prescribed timeframes not worked in India?

A close examination of the Supreme Court's reception of these timeframes is revealing. Let's look at an indicative assortment of four amending provisions that introduced specific outer timeframes in the Code and their interpretation by the Supreme Court.

Prior to 1999, there was no limit on the number of trial adjournments courts could grant. The 1999 Amendment fixed an upper limit of three adjournments that courts could grant during the hearing of a suit. However, in the 2005 case of Salem Advocate Bar Association-II (2005 (6) SCC 344), the Supreme Court interpreted this restriction as not curtailing the court's power to allow more than three adjournments.

This decision has had an active afterlife, having been invoked by tens of high court decisions which proudly proclaim the court's inherent rights to endlessly adjourn.

The 1999 Amendment fixed the timeframe for yet another important provision which directly impacted the court's general power to extend timelines. It specifically disallowed the courts from enlarging the time granted by them for doing any “act prescribed or allowed by the Code“ beyond a maximum period of 30 days. However, in the same 2005 case, the Supreme Court interpreted this timeframe as one not attenuating the inherent power of Indian courts to “pass orders as may be necessary for the ends of justice or to prevent abuse of process of the Court“.

In order to curb the practice of non prosecution of cases filed by litigants, the 1999 Amendment also fixed an outer timeline of 30 days for service of summons on defendants. However, in 2003, in the case of Salem Advocate Bar Association-I (AIR 2003 SC 189) the Supreme Court interpreted this to mean that 30 days limit designated only the outer timeframe within which steps must be takenby the plaintiff to enable the court to issue the summons. In other words, the court held that the provision did not specify a time limit within which summons ought to be served on the defendant by the court. Insertion of another timeframe that was pivotal to curbing delays was introduced in 2002. Prior to 2002, a written statement could be filed within any time as permitted by the court. The 2002 Amendment incorporated a mandatory outer timeline for filing written statement by not allowing the courts to accept it beyond a period of 90 days from the date of service of summons. However, in the 2005 judgment of Kailash vs Nanhku (AIR 2005 SC 2441), the Supreme Court relaxed this statutorily prescribed deadline by interpreting it as merely directory and not mandatory.

It held that courts could use their discretion in unspecified exceptional circumstances to accept delayed written statements. This case has been applied as a virtual carte blanche by lawyers to file written statements beyond 90 days as a matter of course. Thus the exceptional has become the new normal.

Evidently , in each of these illustrations, the Supreme Court relaxes the timeframe inserted by the amendments and restores to the courts discretion to dilute them in accordance with the courts' perceived sense of justice.

These illustrations are not merely fragmentary instances. Similar examples of the undoing of procedure may be found for nearly every provision in the Code that contains a time limit. These illustrations are in fact, a sampling of the adjudicatory manoeuvres by which the Supreme Court has unwittingly come to countenance delay , in contradiction to the express wordings and intent of the Code.

In addition, phrases like “procedures are the handmaiden of justice“, frequently invoked by the Supreme Court, serve as lexical alibis by which departures from procedure are introduced and justified.

Solving the infrastructural deficit by itself would not reduce delays unless a simultaneous effort is made at reforming this jurisprudence of delay that has been allowed to take root. With over 21million cases pending, treating procedural laws as the equal partner rather than a handmaiden of justice would be a better way forward through the crisis.

Causes are many; not shortage of judges alone

`Cases pending not just due to shortage of judges' Oct 11 2016 : The Times of India

Advocating reforms in the justice delivery system, a note prepared by the law ministry for the forthcoming advisory council meeting of National Mission for Justice Delivery and Legal Reforms said, “The linking of problem of pendency of cases in courts with shortage of judges alone may not present the complete picture“.

The ministry studied state-wise comparison of the judge-population ratio, number of cases being instituted in courts, cases disposed per judge per annum and pending cases and observed there was little to link the pendency of cases with the shortage of judges.

The ministry said a variety of factors contributed to delay in disposal of cases including lack of court management systems, frequent adjournments, strikes by lawyers, accumulation of first appeals, indiscriminate use of writ jurisdiction and lack of adequate arrangement to monitor, track and bunch cases for hearing.

States with higher judge population ratio, such as Delhi (ranked second) and Gujarat (fifth) are struggling to dispose pending cases.“Conversely , states such as Tamil Nadu and Punjab, ranked lower in terms of judgepopulation ratio, have comparatively lesser number of pending cases,“ it said.

The state-wise analysis on civil cases instituted in district and subordinate courts between 2005 and 2015 revealed that their number had come down from 40.69 lakh in 2005 to 36.22 lakh in 2015. During the time, pendency of civil cases increased from 72.54 lakh to 84 lakh.

“...in 2005, the working strength of judges in district and subordinate courts was 11,682 which increased to 16,070 in 2015. Despite the increase in judges and decline in cases filed, the pendency increased,“ it said.

‘Stay’ orders delay cases # 6.5 years

The Times of India, Jun 22 2016

Pradeep Thakur

Stays by HCs, SC delay cases by up to 6.5 yrs

Stays on proceedings ordered by high courts and the Supreme Court delay trial by up to 6.5 years, according to a study by the law ministry . Significantly, the average life of a case is 10-15 years. In effect, a case remains in limbo for 50% of its life span because of stays granted by the higher judiciary . The study , which covered the Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat and Odisha HCs, found that trial proceedings had been stayed by superior courts in more than 15,300 civil and criminal cases.

The findings are based on analysis of the annual reports of these HCs. There are 24 HCs in the country , and the data coming out on the number of cases stayed is just a fraction of the total number of cases stayed, a source said. Interestingly , not all HCs are publishing annual reports, making it difficult to ascertain the “accurate and complete picture“.

“There is no uniformity in the manner in which judicial statistics are being provided in annual reports, making it difficult to compare data,“ says the report. The study has also found that the high number of adjournments result in an increase in the average life cycle of cases. It has analysed the number of adjournments granted in Odisha and Rajasthan. Only these two HCs are believed to have provided such data in their annual reports -that too only for their subordinate courts. In Odisha, on an average 51 adjourn ments are granted in civil cases and 33 in criminal cases. For Rajasthan, the adjournments are on average up to 42 in civil cases and 34 in criminal. “It is to be considered that the high number of adjournments hinders the reduction of pendency as is evident from the figures above,“ the report says. The total pendency of cases remained static at around 10.59 lakh in case of subordinate courts in Odisha, and in case of Rajasthan it went up from 14.54 lakh to 14.78 lakh between January and December 2015.

The law ministry had recently also asked all HCs to provide data on their longest reserved judgments. The Calcutta HC reported its longest reserved judgment was for over seven years. It was not known if this was the longest reserved judgment as some of the HCs chose not to respond to the government query . The oldest reserved judgment in the Allahabad HC is pending for three years. The Jharkhand HC has reported its longest pending judgment is for two years while two other HCs of Kerala and Gujarat have reported judgments reserved for more than a year.

Frequent adjournments harass witnesses: HC

The Times of India, Jun 22 2016

Abhinav Garg

The high court has deprecated the practice of criminal courts granting frequent adjournments, leading to harassment of public witnesses who come to depose. In a recent order, Justice Sunita Gupta identified this “attitude of courts of sending witnesses back“ as a major cause of “harassment which discourages public from associating in the investigation of any case.“

The court said, due to being forced to come to court repeatedly , even a public spirited person who may have witnessed a crime avoids joining police and court proceedings.Justice Gupta pointed out that even before coming to court to depose, a witness has been a part of investigation which “itself is a tedious pro cess where a public witness, who is associated, has to spend hours at the spot.“

Favouring fewer adjournments and a sense of urgency on behalf of courts in recording the testimony of a witness, the court reminded the prosecution that “normally , nobody from public is prepared to suffer any inconvenience for the sake of society.“

The other reason, the court explained, for a public witness not readily associating with a criminal investigation is “their harassment that takes place in the courts.“ It added that “normally a public witness should be called once to depose in the court and his testimony should be recorded and he should be discharged.But experience shows that adjournments are given even in criminal cases on all excuses and if adjournments are not given, it is considered as a breach of the right of hearing of the accused...“

Justice Gupta's observations came while upholding the conviction of Rajveer and Rajeev who were awarded a ten year jail term by a special NDPS court earlier. They had filed an appeal challenging the conviction order. Accusing the police of implicating them, the accused said that the absence of a witness clearly casts a doubt on the prosecution version. But the court said there is no reason to disbelieve version of a police witness if other evidence supports the prosecution version.

Judge shortage, adjournments, dubious litigations

The Times of India, May 08 2016

Abhinav Garg & Sana Shakil

Uncharacteristic as it was, Chief Justice of India T S Thakur's emotional outpouring at the conference of chief justices and chief ministers in Delhi impressed upon Prime Minister Narendra Modi and others in the audience that India could not expect to reduce litigation pendency or the backlog of cases without drastically increasing the number of judges.

CJI Thakur's comments were widely discussed in the Delhi high court too but a scrutiny of the two “biennial reports“ brought out by the court administration in the past decade shows the answer may not lie merely in boosting judge numbers. If lawyers and litigants are to be believed, any effective attack on the arrears has to focus on cutting down on adjournments, existing judges putting in more hours of work and maximising the number of court working days in a year.

Consider this: In 2008-09, HC had around 40 judges who managed to dispose of 50,000 cases at an average of over 4,000 a month. The following year saw around 43 judges clearing roughly 43,000 cases for a monthly average of 3,600. The second report showed an average of 40.41 judges bringing to a conclusion 40,861cases in 201011at 3,300 cases per month. This rose to 3,558 disposals per month in 2011-12 though the court was hampered, having to make do with just 36 judges.

The reports may not provide definitive answers, but are handy signposts that show surges and falls in the rate of disposals by division benches. Depending on which jurisdiction of the court the cases were filed under, even fewer benches sometimes cleared a higher number of cases in a year.

“What the data shows is backlog reduction is judgecentric rather than outcome of a cogent system,“ an insider explained. “The court has failed to build and increase its capacity to maximise output and is dependent on few enterprising individuals to keep it afloat from mounting arrears.“ Senior lawyer Aman Lekhi said the bane of protracted litigation required a holistic approach for a solution. “Staff crunch and lack of infrastructure are big problems but other things can improve the situation. The lawyers' tendency to prolong cases has to stop and judges should ensure that arguments are time-bound.“

It is not the Supreme Court or the high court that people approach as first resort. Cases begin in Delhi's district courts, where pendency is at a staggering 2.18 crore cases. Statistics show the shortage of judges is certainly a factor for cases dragging on for years, sometimes even for decades, but here too there are other factors at work.

The varied nature of cases that come before these courts often results in an uneven distribution of workload among the judges. For instance, the number of criminal cases varies from district to district, leaving some courts overburdened and some with very less wo rk. There is also the issue of courts created for special cases.Special courts were created for hearing the coal and 2G scam cases, but no new judge was recruited. In effect, work was redistributed and more cases piled on the existing judges.

A proposal to appoint 210 more judges for the district courts is hanging fire due to lack of land to build more courtrooms where the officers can function from. An alternative plan to expand space in the six court complexes, according to sources, also cannot be carried out, at least at this stage.

When cases from other states are transferred to Delhi for fairer trials on the directions of SC, litigation can be a lengthy process because bringing witnesses to depose in Delhi is a time-consuming exercise. The murder case of former railway minister L N Mishra, transferred to Delhi from Bihar, took, for instance, almost four decades to reach a conclusion.

Frivolous PILs, a common burden for courts across the country , has impacted Delhi HC less after it tightened procedu res a few years ago to screen petitions failing to meet the “public interest“ criteria laid down by the court. In the lower courts, it is a bane. Senior advocate Rebecca John, who specialises in criminal litigation, said, “Dubious litigations are allowed to proceed, adding to the load of overworked courts. Courts, especially superior courts, need to be firm while dealing with frivolous cases and in that I notice a lack of leadership on the part of SC and HCs.“

An insider also pointed out that the concepts of plea bargaining and out-of-court settlements that can quickly resolve some disputes are not encouraged in India. “In some cases, as in bank frauds, the idea is to recover money and not pursue prosecution. They can be settled out of court,“ the insider said.

Red tape and multiplicity of agencies have hobbled the construction of additional courtrooms, forensic labs and intake of more prosecutors, all vital cogs in the justice delivery system. Obviously , it needs more than the tears of a chief justice to get the wheels moving.

’Mindsets allow a culture of delay’

Study shows why merely increasing the number of judges may not be enough to clear the alarming backlog of cases

Much popular attention pertaining to the judi ciary has been on the vexed question of judicial appointments, a power struggle between the government and judges for determining who has the final word on the judiciary's ideological trajectory and the careers of individuals manning it. This has meant that the core issue -unacceptable delays in the judicial system -is sidelined. Delay is mainly seen as an HR issue -appoint more judges and delay will automatically reduce.By blaming delay solely on inadequate capacity , neither the judiciary nor the government is asking the hard questions: What are the mindsets within the judiciary that allow a culture of delay to fester? As of September 30, 2016, the Supreme Court has nearly 61,000 pending cases, official figures say . The high courts have a backlog of more than 40 lakh cases, and all subordinate courts together are yet to dispose of around 2.85 crore cases. At all three levels, courts dispose of fewer cases than are filed.The number of pending cases keeps growing, litigants face even dimmer prospects of their cases being disposed of quickly .

This is the trend across the country . In high courts, 94% of cases have been pending for 5-15 years. In Alla habad, the country's largest and by many accounts, an inefficient court, 925,084 cases are pending. On an average, cases take three years and nine months to get disposed.In Delhi HC, considered publicly as one of the best, 66,281 are pending. It takes an average of two years and eight months to give its verdict in a case. To be fair, delays are not a peculiarly Indian phenomenon. Many advanced countries struggle to provide quick, high-quality justice to citizens. But in India the scale of the problem is unprecedented.

Focusing on capac ity alone won't reduce delays.A pervasive reason for delays is adjournments. A study by the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy (VCLP) conducted on Delhi HC found that in 91% of cases delayed over two years, adjournments were sought and granted. Merely increasing the number of judges won't help because adjournments are acceptable in our judicial system. These encourage delaying tactics, block judicial time, prevent effective case m a n a g e m e n t and impoverish litigants. They deter many from seeking access to for mal justice. Apart from the lawyers, who often charge per hearing, none benefits.

An initiative by VCLP -Justice, Access and Low ering Delays in India (Jal di) -seeks to address the problem. It talks of reducing government litigation, com pulsory use of mediation and other alternative dispute resolution mechanisms. It mentions simplifying proce dures, recommending pre cise capacity reinforcements and use of technology . The goal is to find a way to clear all backlog in the courts within six years.

This isn't unrealistic. In Singapore, the implementa tion of similar reforms in the 1990s led to astonishing re sults, 95% of civil and 99% of criminal cases were disposed of in 1999. The average length of commercial cases fell from around six years in the 1980s to 1.25 years in 2000. The pend ing cases count hasn't grown substantially since.

While implementing such , reforms will present chal lenges, it is critical that the public narrative around de lays changes. Delay in courts is not an HR issue -it is a question of the growth of a culture that has made delays acceptable. It impacts our ease of doing business rank ings and hinders access to justice to the mazdoor whose employment has been unlawfully terminated.

Scarcely has there been an issue that cries out louder for the government and the judiciary to secure the constitutional mandate of speedy and effective access to justice.Arghya Sengupta is research director, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy The data in the graphic alongside is from a report on inefficiency & judicial delay (Delhi high court) by Nitika Khaitan, Shalini Seetharam, Sumathi Chandrashekaran of the Judicial Reforms Initiative at the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy

Inefficiency to blame

See graphic

Supreme Court on pending cases

Curb adjournments, speed up trials, SC tells lower courts

‘Law Being Violated With Impunity’

Dhananjay Mahapatra The Times of India 2013/05/15

At a time when people are getting impatient with judicial delays, the Supreme Court has stepped in to curb the tendency of trial courts to liberally grant adjournments at the instance of lawyers. It said that trial courts were flouting “with impunity” the Criminal Procedure Code mandate for conducting proceedings on a day-to-day basis after witness examination starts and were easily granting adjournments.

A bench of Justices K S Radhakrishnan and Dipak Misra expressed “anguish, agony and concern” over adjournments granted by a Punjab trial court in a bride burning case which stretched the process of examination of witnesses to more than two years.

“On perusal of dates of examination-in-chief and crossexamination, it neither requires Solomon’s wisdom nor Argus eyes (mythological giant with 100 eyes) scrutiny to observe that the trial was conducted in an absolute piecemeal manner as if it was required to be held at the mercy of the counsel,” Justice Misra, who authored the judgment, said.

Referring to Section 309 of the CrPC, the bench said once a case reached the stage of examination of witnesses, the law mandated that it “shall be continued from day-to-day until all witnesses in attendance have been examined”. The section provides that if for some unavoidable reason the court was to grant adjournment, it must record its reasons in writing.

‘Trial judge can’t be a mute spectator to litigants’ tactics’

The Supreme Court expressed its anguish over the tendency of trial courts to liberally grant adjourments. “It is apt to note here that this court expressed its distress that it has become a common practice and regular occurrence that the trial courts flout the legislative command with impunity,” the bench of Justices K S Radhakrishnan and Dipak Misra said.

The bench added that the criminal justice dispensation system casts a heavy burden on the trial judge to have full control over the proceedings. “The criminal justice system has to be placed on a proper pedestal and it can’t be left to the whims and fancies of the parties or their counsel.”

“A trial judge cannot be a mute spectator to the trial being controlled by the parties, for it is his primary duty to monitor the trial and such monitoring has to be in consonance with the CrPC ,” the bench said. The SC wanted trial judges to keep in mind the mandate of the CrPC and not get guided by their thinking.

“They cannot abandon their responsibility. It should be borne in mind that the whole dispensation of criminal justice system at the ground level rests on how a trial is conducted. It needs no special emphasis to state that dispensation of criminal justice system is not only a concern of the bench but has to be the concern of the bar,” it said.

On the case of bride burning and ill-treatment meted out to daughters-in-law, the apex court said, “A daughter-in-law is to be treated as a member of the family with warmth and affection and not as a stranger with despicable and ignoble indifference. She should not be treated as a housemaid. No impression should be given that she can be thrown out of her matrimonial home at any time.”

The Times of India’s View

Given the enormous backlog of cases in Indian courts, particularly at the lower levels, any measure that helps speed up processes is welcome. Getting rid of needless adjournments is certainly an important step and the Supreme Court must be thanked for stepping in to curb them. We hope that the implementation of this directive will be rigorous.

SC blames HCs for delay in hearing criminal cases

Apex Court Finds 2,280 Cases Of Rape, Murder Stayed By HCs

Dhananjay Mahapatra | TNN

From the archives of The Times of India 2007, 2009

New Delhi: Ever wondered why so many accused in heinous crimes — murder, rape, kidnapping and dacoity — roam around for years before the law catches up with them?

This question bothered the Supreme Court a lot and it found that the High Courts were mainly responsible for such a sorry state of affairs. For, they have stayed the proceedings in these cases and forgotten all about them for years.

As many as 2,280 cases relating to murder, rape, kidnapping and dacoity have been stayed by HCs at various — FIR, investigation, framing of charges and trial — stages and then left in the limbo, possibly allowing the accused to remain at large on bail.

A Bench comprising Justices G S Singhvi and A K Ganguly sought assistance from Solicitor General Gopal Subramaniam for collating data on cases relating to the four categories of heinous crimes which have been stayed by HCs after it found an identical situation pointed out in a petition filed by Imtiaz Ahmed, where the Allahabad HC had stayed a criminal case since April 2003.

The efforts by the SG to collate such cases threw up startling facts:

Murder cases stayed at various stages by HCs were 1,021 (45% of the total cases), rape cases 492, kidnapping cases 550 and dacoity 217

As many as 41% of the 2,280 cases were pending for 2-6 years and 8% for more than 8 years. Of a total of 178 cases pending for more than 6 years, 97 were murder cases

Calcutta High Court appears to be the most liberal when it came to staying cases relating to heinous crimes accounting for 31% of the 2,280 cases. Allahabad High Court was not far behind having stayed 29% of the cases

In most of the cases across the HCs, the duration for which the case is pending varied from 1 to 4 years. It is seen that 34 out of 201 cases in Patna HC and 33 out of 653 cases in Allahabad HC were pending for more than 8 years

After perusing the enormity of the situation and having regard to the case in hand that related to Allahabad HC, the Bench headed by Justice Singhvi requested the counsel for the High Court to furnish data about the number of cases which have been stayed at the stage of investigation or trial and listed the matter for further hearing on July 9.

The report was submitted to the court by Subramaniam, who took assistance of Dr Pronab Sen and Dr G S Manna, secretary and deputy director in the ministry of statistics and programme implementation, in studying the data supplied by various HCs.

The SG, in the concluding part of the report, said “the fact-finding exercise by the Supreme Court has revealed a problem of serious dimension” and suggested that the apex court would be well within its jurisdiction to direct the HCs to dispose of the matter within a year from the date of grant of stay in cases relating to heinous crimes.

If a case was not disposed of within a year, the concerned judge must record the reasons which should be communicated to the concerned chief justice of the HC, Subramaniam suggested.

SC: ‘Flood of appeals affecting verdicts’

From the archives of The Times of India 2010

Pressure Does Not Give Judges Enough Time To Deliberate Upon Cases: SC

Dhananjay Mahapatra | TNN

New Delhi: A concern expressed in hushed voices by senior lawyers for quite some time in the corridors of the apex court has now become official.

The Supreme Court has admitted that deluge of appeals is affecting the quality of its judgments, which are abided by all and sundry as the law of the land.

It does not want the apex court, set up to decide constitutional issues and inter-state disputes in addition to giving opinion to the President on tricky legal questions, to get reduced to just a final court of appeal being mired in the volumes.

To devise a way out of the jungle of files eating into judicial time and affecting the quality, a bench comprising Justices Markandey Katju and R M Lodha said the time has come for a Constitution bench to firmly lay down guidelines as to the categories of cases that the apex court should entertain rather than get engaged in deciding routine appeals or mundane issues.

The judgment comes at a time when a flood of appeals in the last four years has given rise to huge pendency in the Supreme Court, which for the first time in a decade reported a backlog of over 50,000 cases in March last year. Since then it has been on the increase and on January 1, 2010, the pendency stood at 55,791 cases.

Searching for a solution, the bench found the suggestions of senior advocate K K Venugopal quite valuable. Venugopal in a recent speech had said that the SC should deal with five categories of cases — those involving interpretation of the Constitution, matters of national and public importance, validity of laws, judicial review of constitutional amendments and settling difference of opinion between high courts.

On its own it added two more categories — where there is a grave miscarriage of justice and where a fundamental right of a person is prima facie violated.

It said: “The apex court lays down the law for the whole country and it should have more time to deliberate upon the cases it hears before rendering judgments.”

“However, sadly the position today is that it is under such pressure because of the immense volume of cases in the court that judges do not get sufficient time to deliberate over the cases, which they deserve, and this is bound to affect the quality of out judgments,” the bench said.

It issued notices to the SC Bar Association, Bar Council of India and the SC Advocates on Record Association to assist the constitution bench in framing appropriate guidelines to limit the flooding of appeals.

With the computerization of the Supreme Court registry and use of information technology in the docket management, the pendency of the cases in the 1990s was brought down from over one lakh to a manageable 20,000.

But, the rush of litigants, despite an increased disposal rate, has proved more than a match for the judges, who despite hearing nearly 80 cases per day have not been able to bring it down.

The pendency started creeping northwards since 2006, when it stood at 34,649. In January 2007, it became 39,780 while it registered a steep jump to 46,926 in January 2008.

By the start of 2009, it was within handshake distance of the 50,000-mark as the pending cases numbered 49,819. The half-a-lakh pendency mark was crossed on March 31, 2009.

SC: Bail Plea In 1 Week, Magisterial Trial In 6 Months

`Fix Bail Plea In 1 Week, Magisterial Trial In 6 Mths'

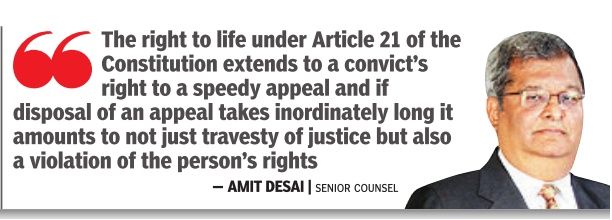

Holding that speedy trial in criminal cases is part of the fundamental rights of an accused, the Supreme Court has suggested a time-frame for lower courts to decide a case to ensure that the accused do not languish in jail due to prolonged proceedings.

A bench of Justices A K Goel and U U Lalit asked the high courts to issue directions to subordinate courts to decide bail applications within a week and in cases where the accused in custody, magisterial trial should be concluded within six months and sessions trial (for offences punishable by more than seven years) within two years. It said efforts should be made to dispose of all cases more than five years' old by the end of the year.

Expressing concern over alarming number of old cases pending in lower courts, the bench said all-out efforts should be made for their quick disposal. The total number of more than five-year old cases in subordinate courts at the end of the year 2015 is said to be 43,19,693 and number of under-trials detained for more than five years at the end of the year 2015 is said to be 3599.

“Speedy trial is a part of reasonable, fair and just procedure guaranteed under Article 21. This Constitutional right cannot be denied even on the plea of non-availability of financial resources. The court is entitled to issue directions to augment and strengthen investigating machinery , setting-up of new courts, building new court houses, providing more staff and equipment to the courts, appointment of additional judges and other measures as are necessary for speedy trial,“ the bench said.

It said that high courts should regularly monitor performance of judicial officers and the timelines should be made the touchstone for assessment of their performance in annual confidential reports.

“We do consider it necessary to direct that steps be taken forthwith by all concerned to effectuate the mandate of the fundamental right un der Article 21 especially with regard to persons in custody in view of the directions already issued by this court. It is desirable that each high court frames its annual action plan fixing a tentative time limit for subordinate courts for deciding criminal trial of persons in custody and other long pending cases and monitors implementation of such time-lines periodically,“ the bench said.

The bench said vested interests and unscrupulous elements would always try to delay the proceedings but determined efforts are required to be made by the judiciary for success of the mission.

“Judicial service as well as legal service are not like any other services. They are missions for serving the society . The mission is not achieved if the litigant who is waiting in the queue does not get his turn for a long time. Chief Justices and Chief Ministers have resolved that all cases must be disposed of within five years which by any standard is quite a long time for a case to be decided in the first court,“ it said.

It also asked the high courts to ensure that bail applications filed before them are decided within one month and criminal appeals where accused are in custody for more than five years are concluded at the earliest.

The extent of the problem

320 years to clear the backlog

From the archives of The Times of India 2010

‘It’ll take 320 years to clear legal backlog’

TIMES NEWS NETWORK

Hyderabad: It will take the Indian judiciary 320 years to clear the backlog of 31.28 million cases. The staggering admission came on Saturday from someone who knows the way the courts work all too well — Justice V V S Rao of the Andhra Pradesh high court.

‘‘If one considers the total pendency of cases in the Indian judicial system, every judge in the country will have an average load of about 2,147 cases,’’ Justice Rao said. India has 14,576 judges as against the sanctioned strength of 17,641, working out to a ratio of 10.5 judges per million population, he said. In 2002, the Supreme Court suggested it be 50.

‘Court cases increase with rise in literacy’

It will take the Indian judiciary 320 years to clear the backlog of 31.28 million cases, says Justice V V S Rao of the Andhra Pradesh high court. If the norm of 50 judicial officers per million becomes a reality by 2030 when the country’s population would be 1.5 to 1.7 billion, the number of judges would go up to 1.25 lakh dealing with 300 million cases. A recent study indicated that the number of new cases has direct relationship with increasing literacy rate and awareness, the judge said.

Citing the example of Kerala, a high literacy state, Justice Rao said with awareness, 28 new cases per 1,000 population per annum have been added, whereas in Bihar, the figure stands at just three, he said. He summed up the Indian situation by quoting from the journal of International Law and Politics which said: ‘‘The typical lifespan of a civil litigation in India presents a sad picture. Records of new filings are kept by hand and documents filed in court house are frequently misplaced or lost.’’ TNN

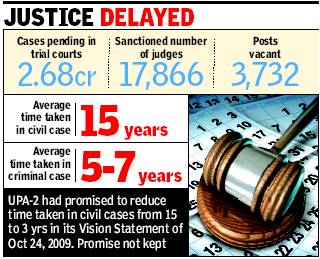

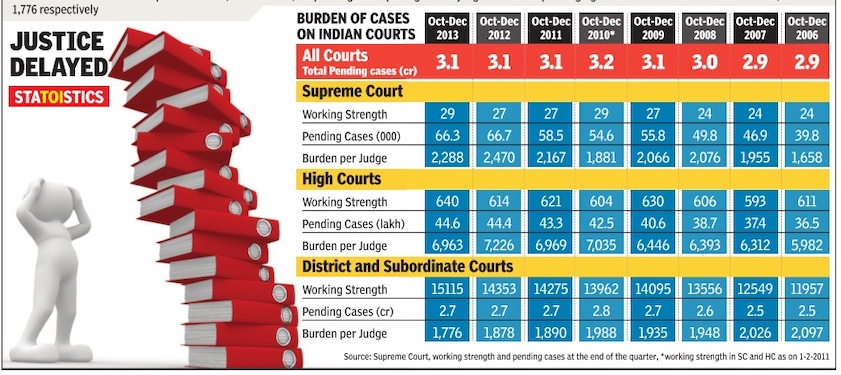

2006-13: Pending cases

Apr 06 2015

Perhaps one of the biggest challenges faced by the Indian judiciary is the massive burden of pending cases. As of the last quarter of 2013, there were over 3 crore pending cases in various courts. In the eight years between 2006 and 2013, the number of pending cases increased at each level of courts. The increase, however, is steeper at the higher levels compared to district and subordinate courts. Also, the burden of cases per judge has increased in the SC and HCs while it has decreased in district courts. As of the last quarter of 2013, there were 6,963 pending cases per high court judge. The corresponding figures for SC and district courts were 2,288 and 1,776 respectively.

2006-May 2016

The Times of India, Aug 11 2016

Dhananjay Mahapatra

2.18 Crore Cases Pending In Courts Till May 31, Reveals SC

22L cases stuck for more than 10 yrs

Reasons may be many , from inadequate number of trial judges to lack of infrastructure, but the snailpaced judicial system continues to carry a large chunk of cases that have been on its back for more than a decade.

Statistics released by the Supreme Court say that by May 31, courts across the country recorded a pendency of 2.18 crore cases, of which 27% or 59.3 lakh cases have been pending for more than five years entailing litigants to visit the courts several times.

Of the 59.3 lakh cases pending for more than five years, as many as 22.3 lakh cases have been on board of courts for more than 10 years, the eCommittee statistics revealed. The eCommittee conceded that the national average of disposing of very old cases has come down.

The National Judicial Data Grid statistics revealed that at the end of April 30, there were 27.4 lakh undated cases pending in various courts and it increased to 28.8 lakh cases by May 31.

The states which reported the largest number of more than 10-year-old cases are: Uttar Pradesh -6.6 lakh; Gujarat -5.2 lakh; Maharashtra -2.51 lakh; Bihar -2.3 lakh; Odisha -1.83 lakh and West Bengal 1.51 lakh. Among the larger states, Punjab recorded the least number of more than 10-year-old cases with 1,328 of them pending.

From time to time, the Chief Justice of India on be half of the judiciary and the governments have been resolving to expeditiously dispose of old cases and cases filed by senior citizens and women.But, the message does not appear to have had the desired effect at the ground level.

As many as 7.1 lakh cases filed by senior citizens and 21.4 lakh cases filed by women are pending in trial courts. Karnataka, which had done reasonably well in disposing of over 10-year-old cases, lags in attending to cases filed by senior citizens. States with large pendency of cases filed by senior citizens are: Maharashtra -2.07 lakhs; Karnataka -1.07 lakh; Tamil Nadu 64,018; UP -63,762; Gujarat 49,837 cases.

Highest pendency of cases filed by women has been reported from UP, which has 4.4 lakh such cases.

Other states where large pendency of cases initiated by women are: Maharashtra -2.7 lakh; Bihar -2.17 lakh; West Bengal -1.72 lakh; Karnataka -1.47 lakh; Tamil Nadu -1.37 lakh and Rajasthan -1.19 lakh.

2012-14: Pendency in subordinate/ district courts

The Times of India, Jan 08 2016

UP lower courts show the way in disposing of cases

More Than 3cr Cases Pending In HCs, Subordinate Courts

The performance of subordinate judiciary in UP , surprisingly , has mproved considerably compared to other states. Last month they had disposed of 1,04,425 cases as against 76,479 new ones registered. The rate at which pendency has been reduced in the last three years has been impressive too. The disposal of cases by he subordinate and district courts in UP has gone up by almost 2 lakh a year in the last hree years -from 27.98 lakh cases disposed of in 2012 to 31.82 lakh in 2014. Among other states, Karnataka and Kerala have also shown better performance during this period where disposals have gone up from 10.35 lakh to 13.67 lakh cases and 11 lakh to 13.55 lakh cases, respectively.

Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Tamil Nadu are among those which need to further strengthen their court procedure, to avoid being tagged laggards. The subordinate courts in Maharashtra had disposed of 20.48 lakh cases in 2012, which has come down to 15.36 lakh cases in 2014. Similar is the rend in MP and Tamil Nadu.

The statistics released by he law ministry recently indicate the performance of subordinate judiciary has overall improved in the last ew years. In comparison, the rend in 24 High Courts together show a dismal per ormance. More than 3 crore cases are pending in HCs and subordinate courts together -41.50 lakh in HCs and 2.64 crore in subordinate and dis rict courts across the coun ry. UP still remains at the top with highest number of pendency at 48 lakh cases, fol owed by Maharashtra, Gujarat, West Bengal and Bihar.

2012-14/ 15: Pendency down, except for crimes against children

The Times of India, January 27, 2016

Pradeep Thakur

Pendency down, but up 59% in cases of crimes against kids

Pendency of cases across all levels of the judiciary has gone down, but it has sharply increased in cases of crimes against children, with Delhi recording a 71% rise. In what also points to a spurt in crimes against kids, the countrywide pendency of such cases went up from 74,400 in 2012 to 125,000 in 2014, a rise of over 59%.

According to the law ministry, in 2012, at least 3,500 cases of offence against children were pending in various courts in the capital. This went up to 4,253 at the end of 2013 and to 6,021by the next year.

Maharashtra had the highest number of pending cases of crimes against children, ahead of UP. The western state had 18,000 pending cases in 2012 which increased to 21,255 the next year and to 25,302 in 25,302 in 2014. In UP, such pendency increased from 11,115 to 25,011during this period.

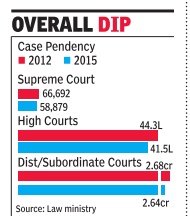

MP ranked third and Gujarat fourth. While pendency in MP increased from 12,159 to 18,080 between 2012 and 2014, it went up in Gujarat from 5,596 to 7,250. In Karnataka, the rise was from 887 cases in 2012 to 3,000 in 2014. The overall pendency of cases showed a down ward trend. According to the ministry , the pendency in SC came down from 66,692 in 2012 to 58,879 in 2015. In the 24 HCs, it decreased from 44.34 lakh to 41.53 lakh during the same period. Even in the 15,000odd district and subordinate courts, pendency came down from 2.68 crore to 2.64 crore.

Though the states have set up special courts under the POCSO Act for trial of such cases, this has not helped as more and more cases have been registered, adding to the pendency list. There are more than 600 special courts to try cases of crimes against children in the country . UP has the maximum with 75 courts.

2014: 3.19 crore pending cases

Jan 13 2015 See graphic.

COURTING TROUBLE

Indian courts are known for the colossal pile of pending cases. According to the latest data available on the Supreme Court website, there are about 31.9 million pending court cases in India, more than the population of countries like Saudi Arabia, Malaysia and so on. The data also shows that there are sizeable number of vacancies at all levels of courts -19.4% in the Supreme Court, 29.2% in high courts and about 22% in various district and subordinate courts. Among high courts, the Allahabad HC has the highest number of pending cases followed by Madras and Bombay. At lower levels, the highest pendency is in Uttar Pradesh

2016: Pendency of cases

The Times of India, Mar 22 2016

Pradeep Thakur

Allahabad tops in pendency, reveals study

In a reflection of the slow pace of justice delivery in India, a study has found that it takes more than three years on an average before a case is disposed of in the high courts. The study conducted by Bengaluru-based NGO Daksh on 21 high courts has found the average pendency of a case in the Allahabad HC is over three-and-half years or 1,337 days, topping the chart. It is followed by Bombay HC which has 1,245 days of average pendency of a case.

The Gujarat HC comes third, taking 1,186 days for a case to be disposed of, followed by Patna (1,073), Karnataka (982) and Delhi (959).The Sikkim HC has the lowest average pendency of 281 days, also for the fact that the state has one of the lowest number of cases registered. The oldest case yet to be disposed of is of January 1, 1958.

“The study has also reviewed 17 lakh cases in 417 district courts, the oldest case being of November 22, 1931.In the district courts, the av erage pendency has been more than five years or 1,953 days as compared to 1,128 days in HCs,“ said Kishore Mandyam, co-founder of Daksh. The database of number of cases used to arrive at the average pendency days of a case has been almost similar for both district and high courts.

The NGO, which is collaborating with the law ministry to analyse its data, has reviewed 18 lakh cases and 59.60 lakh appearanceshearings from 21HCs.

According to the study , besides Sikkim, the HCs hat have faster disposal records include Uttarakhand, Goa, Orissa, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand and Kera a, in that order. Though law minister Sadananda Gowda had last year written to all chief justices of HCs for compiling an annual report isting performances of the r courts -pendency of cases, disposal rates, etc. -and put the same on their websites for public scrutiny , barring HCs of Delhi, Himachal, J&K, Jharkhand, Kerala, Madras and Tripura, none had responded to he government's request.

September 2016/ 10% cases over 10 years old

See graphic.

Acquittal rate

High rate in Delhi, 2011-15

The Times of India, May 05 2016

HC: Poor probe led to high acquittal rate

More than 80% of criminal cases decided by the Delhi high court in the past five years ended in acquittal while the figure hovered around 60% for sessions courts in the capital.

Appalled by the high acquittal rate, a bench of justices B D Ahmed and Sanjeev Sachdeva on Wednesday blasted Delhi Police for its “shoddy probe“, pointing out that “innocents may have been sent for trial and guilty gone unpunished“ because of this trend.

The court's stinging comments came on a status report filed by the police disclosing data of total cases decided by the Supreme Court, the Delhi HC and sessions courts in the past five years.Referring to the “revealing statistics“, the HC bench said, “For this reason, we have been pressing upon the need to bifurcate law and order duties so that investigation wing improves. We also stressed the need for proper scientific methodology , increase in manpower but these concerns take a back seat for governments of the day .“

The police report showed that of 725 cases in HC, 588 ended in acquittal while the accused were convicted in 138 cases. With regard to crimes against women, acquittals in sessions court were over 71% as against 84% in the Delhi HC.

Saying it is “deeply disap pointed“, the bench slammed the police. “People are getting raped, molested, harassed, murdered and acquittal rate is 80 to 90%. Then court is blamed for acquittals that we allowed culprit to go scot-free. But the reason is shoddy investigation by police. It means they have apprehended a criminal but because of poor quality of investigation and evidence, court acquits the criminal...because of shoddy investigation, innocent people get arrested,“ the court noted.

According to the report filed in a suo motu case related to policing and security following the Nirbhaya case, the police revealed that of 14,270 session courts cases, 8,667 ended in acquittal while 5,603 ended in conviction in the past five year.

“Two of the most material things for any human being are life and liberty , which should never take a back seat“ the bench reminded the counsel appearing for the Delhi government, police and the Centre.

The high court asked the Delhi government to file a detailed status report on the backlog of samples, which are yet to be tested in forensic science laboratories and also the number of samples tested in past three years. Zeroing in on the lack of sufficient FSLs as one of the main reasons for delay in trial and mounting arrears, the court said report would have to indicate the number of samples tested in the past three years and the capacity of each lab individually and together. The court will take up the matter on May 18.

As of now, there are only two functional forensic labs in Delhi--at Chanakyapuri and Rohini--and the backlog of samples is over 8,000. A report from these labs is received only after three-four years, the court was informed.

The Centre in its affidavit said that Delhi Police had forwarded majority of its proposals for manpower directly to MHA. It said a high-level committee had been set up to take a holistic view regarding manpower requirement.

Pendency, strategies to tackle

Courts must follow case timelines

Courts must follow case timelines or take the rap, March 29, 2017: The Times of India

Former chief justice of Delhi high court, A P Shah, shares his take on tackling judicial inefficiency

ON JUDICIAL DELAYS

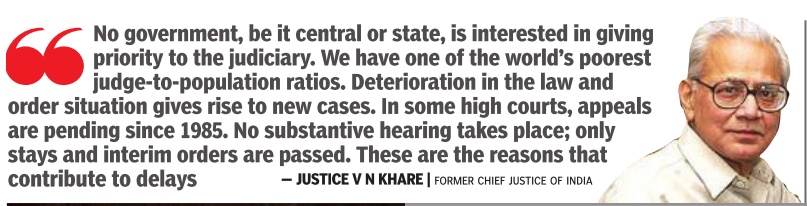

Judicial delay is often attributed solely to court vacancies. But paucity of judges is not the only reason for pendency . There is an absence of evaluation of courts' performance and specific reasons for delay have not yet been studied.

Vidhi's report on the Delhi high court is a first step forward.Inefficiencies in the system must be examined: the court and other actors are not functioning at optimum efficiency , and the extent to which this contributes to delay must be tracked from the trial court stage itself.

ON HOW TO IMPROVE EFFICIENCY

What's troubling is that case timelines are never followed. The culture of adjournment and non-compliance is so deeply rooted that no thought is given to case management. Both the Bar and the bench are equally responsible; advocates use multiple adjournments as a strategic tool, and courts do not adhere to procedural timeframes.

Although exemplary costs are sometimes levied on dilatory tactics, it's mostly ad-hoc and not a matter of institutional policy or practice. It is also common for lawyers to engage in unnecessarily long arguments and for judges to write overly long judgments. Since case management is completely absent, hundreds of matters are listed on one day , and insufficient time is left in court to hear cases. Courts need to implement case timelines and there must be serious consequences for not following them.

ON HOW COURTS CAN AID RESEARCH ON DELAY

Professional managers are needed in courts to improve data management. Judges are still given these administrative tasks.As a result, data collection is non-uniform, defective and, at times, misleading. What Delhi high court has done is laudable but not sufficient. The judiciary needs better data management but has been reluctant to engage external experts, even for managerial tasks. There is a misconception that technology will solve all of judiciary's problems. That is the role of judicial policy-making; technology is a small part of the solution.

Retired High Court judges, use of services

The Hindu, November 6, 2016

KRISHNADAS RAJAGOPAL

Retired judges to wield the gavel again

It took the government six months to agree to a resolution passed by the judiciary to re-employ them to cut pendency.

The Union government has agreed to a resolution passed by the judiciary in the Chief Justices and Chief Ministers Annual Conference in 2016 to use the services of retired High Court judges with proven integrity and track record to tackle pendency of cases.

The resolution, forwarded by the Delay and Arrears Committees of the judiciary, had been hanging fire since April 2016.

The provision to use the services of retired judges is open to the Chief Justices of High Courts under Article 224A of the Constitution with the previous consent of the President as an extraordinary measure to tide over case pile-ups.

As per the minutes of the April resolution, “keeping in view the large pendency of civil and criminal cases, especially criminal appeals, where convicts are in jail and having due regard to the recommendation made by the 17th Law Commission of India in 2003, the Chief Justices will actively have regard to the provision of Article 224A of the Constitution as a source for enhancing the strength of judges to deal with the backlog of cases for a period of two years or the age of sixty five years, whichever is later until a five plus zero pendency is achieved.”

‘Five plus zero’ initiative

‘Five plus zero’ is an initiative by which cases pending over five years are taken up on priority basis and their numbers are brought down to zero.

The conference minutes considered the report of the committees about delay in case disposal in the High Courts with great concern. “The reports submitted by the Delay and Arrears Committees of various High Courts have indicated a need to prioritise areas of immediate concern in the disposal of pending cases.”

These concerns highlighted in the conference includes: The pendency of cases in the High Court has been stagnant for over three years; 43 per cent of the pendency is of cases of over five years; concentration of ‘five years plus’ cases in a few High Courts; and stagnant pendency figures of five years plus cases (33.5 per cent in 2015) in district courts.

Accordingly, it was resolved that all High Courts shall assign top-most priority for disposal of cases which are pending for more than five years.

In High Courts, where arrears of cases pending for more than five years are concentrated shall facilitate their disposal in a “mission mode.”

The High Courts shall progressively thereafter set a target of disposing of cases pending for more than four years. The Conference had resolved that while prioritising the disposal of cases pending in the district courts for more than five years, additional incentives for the judges of the district judiciary be considered.

MoP on appointments

The agreement on the minutes comes at a time when the Executive and the Judiciary are trying to find a common ground on the memorandum of procedure for judicial appointments in High Courts and ths Supreme Court.

As on June 30, 2016 while the total sanctioned strength was 21,303, the subordinate courts were functioning with 16,192 judicial officers — a shortage of 5,111.

The 24 High Courts face a shortage of nearly 450 judges. Nearly three crore cases are pending in courts across India.

Region-wise

The six worst hit states

The data in this section seems to be for 2006-16

90% of 23 lakh cases pending for over 10 years are in 6 states Sep 21 2016 : The Times of India

Six states account for around 90% of the 23 lakh cases pending around the country that are older than 10 years, though not all of them are the largest states in terms of overall pendency .

UP accounts for 30% of all 10-year-old cases pending countrywide, followed by Gujarat with 22%, Maharashtra (11%), Bihar (10%), Odisha (8%) and West Bengal (8%).Out of 2.29 crore cases pending in subordinate courts across the country , 22.95 lakh are older than 10 years. In addition, 40 lakh cases have been pending between five and 10 years. According to the National Judicial Data Grid, UP has close to 7 lakh cases which have been pending for 10 years or more. Gujarat has 5.13 lakh such cases, Maharashtra 2.57 lakh, Bihar 2.37 lakh, Odisha 1.82 lakh and West Bengal 1.72 lakh.

Many of these cases remain unresolved in subordinate courts for decades and are reflective of the slow moving justice delivery system.Around 71% of all cases pending for over 10 years are criminal cases where a court is bound to dispose of the matter in a fixed time.

However, of late, the judicial system in some states have shown the willingness to take up older cases on priority. For instance, Gujarat, which has the second highest pendency of old cases, disposed of 9,000 last month -over 6,400 criminal and 2,500 civil cases. UP has performed well too, with 6,600 cases older than 10 years disposed off last month alone, half of these were criminal cases. There are also huge va cancies in lower courts across the country . At least 4,432 judges' posts were vacant as of December 2015. Out of a sanctioned strength of 20,502 judges for subordinate courts, the strength stood at 16,050 last year.

Trial courts: Delhi, delays reduced

Case backlog shrinks in trial courts

30% Reduction Since 2011-End, But No Change In Number Of Criminal Cases

Smriti Singh TNN

The Times of India 2013/08/13

New Delhi: Trial courts in the capital have managed to reduce pending cases by 30% in the last one-and-a-half years. A recent report released by the Delhi district courts on the pendency of cases states that around five lakh cases are pending before the lower judiciary this year as against more than seven lakh at the end of 2011. This figure includes all the criminal cases and civil disputes before the magisterial courts and the district and sessions courts.

There has also been a significant reduction of 50% in the pending cases of dishonoured cheques, major component of the backlog. From 2.2 lakh cheque bounce cases pending in 2011, the courts now have 1.06 lakh. Legal experts say the drop in pending cases is a result of measures adopted by the judiciary, such as the setting up of special courts and the ‘five-plus-zero’ initiative.

Last year, the Delhi high court had asked judges to “identify” cases which have been pending for more than five years and take them up on priority. They were also asked to dispose of such cases within six months.

The circular issued by the HC had also asked the courts to bring down the pendency of ‘cheque bounce’ cases under the Negotiable Instruments Act by 50% before December 2012. To achieve the target, the senior judges were asked to “ensure” that the metropolitan magistrates dealing with such cases are provided with “adequate staff and support from police stations in executing summons and warrants”.

While the targets in the cheque dishonour and traffic challan cases seem to have been achieved, there is no decline in the number of criminal cases pending before the sessions courts. In all, 18,564 sessions-triable cases, which have a punishment of seven years and above, are pending. This figure includes 1,043 rape cases, 47 cases of gang rape and 212 cases pending under the new Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO).

Even as six fast-track courts have been set up to try cases of sexual offences against women, sources said it is difficult to bring down the pendency in such cases to zero due to the increasing crime rate. “Pendency in criminal cases usually stays constant as new cases are filed every day, and despite regular disposal the new cases add on to the existing numbers,” said a judge on the condition of anonymity.

Also, adding to this year’s backlog are more than 1 lakh cases pending before magisterial courts. These include petty offences in which the maximum punishment is up to three years.

Sources say many measures have been adopted by the courts to tackle the mounting number of cases. Besides the five-plus-zero initiative and the increased number of judges in the lower judiciary, the courts are also required to send their disposal rate in every quarter of the year. Mega lok Adalats are also being held on a regular basis to deal with compoundable offences—those in which a settlement can be achieved.

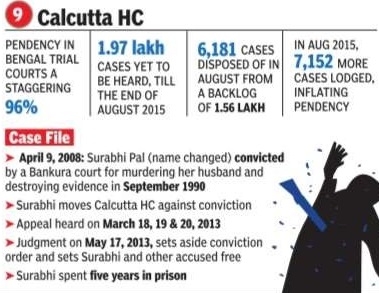

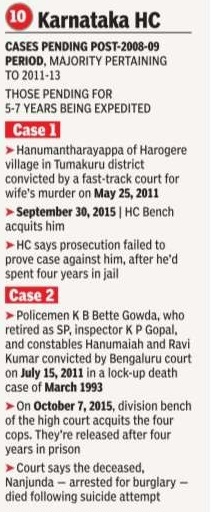

2015: Pendency 45 lakh in 24 HCs

The Times of India, Oct 15 2015

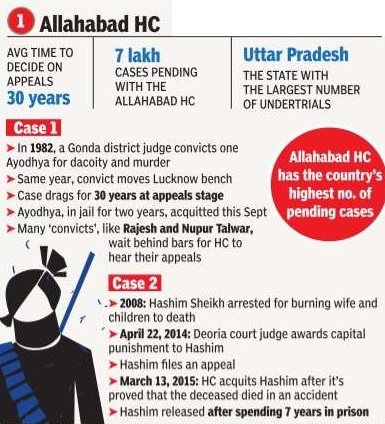

The wheels of justice, the saying goes, grind slowly but grind exceedingly fine. In the Indian context, it would be more true to say that they grind so exceedingly slowly that there can be nothing fine about the outcome. When we set out to look at instances of gross miscarriage of justice, we found several cases where people were convicted of heinous crimes and locked up for years before being found innocent on appeal. Given the state of our high courts, this is hardly surprising. Consider the cold statistics first. As of end of June 2014, there were nearly 45 lakh cases pending in the country's 24 high courts. That's an average of nearly 2 lakh cases per high court. This is mindboggling in itself, but pales in comparison to the situation in Allahabad HC, where approximately 7 lakh cases are pending.

The extent of pending cases is only to be expected when you look a little deeper into the same official data. It also tells you that as of end of June 2014, there were 265 vacancies for judges in the HCs against a sanctioned strength of 906, a shortfall of almost 30%. In the case of Allahabad HC, 70 of 160 positions were vacant or, about 44% of the judges required for the voluminous work have not been appointed.

Of the cases pending, about 10.3 lakh in all the HCs and 3.5 lakh in Allahabad alone were criminal cases. Assume for argument's sake that just one in a hundred of these cases will end up in the acquittal of the person or persons convicted by the lower courts -the actual acquittal rate will, of course, be much higher, but even if 1% of those convicted is innocent -then over 10,000 people in the country are wrongly locked currently . They are in jail despite being innocent of the crime they are said to have committed. For a system supposedly based on the principle that it is better for ten guilty people to go scot-free than for one innocent to be wrongly convicted, that is a shocking statistic.

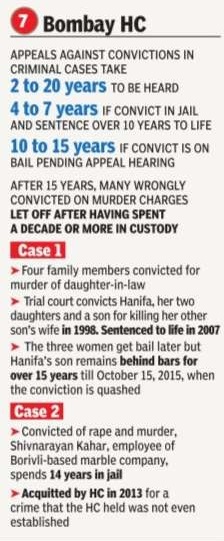

It isn't as if a person who has been wrongly convicted can count on a quick reprieve on appeal. In Allahabad HC, for instance, it takes, on average, 30 years for appeals against conviction in a lower court to be decided. The Rajasthan HC also has criminal cases pending since 1985. In Bombay HC, you could wait anywhere between two and 20 years, but the average time it takes for an appeal to be heard is four to seven years if a convict is in jail and the sentence is over 10 years; and 10-15 years if the convict is on bail pending the appeal hearing.

The exact period of waiting may vary from HC to HC, but in most cases it runs into several years. And if the crime involved is murder, the wrongfully convicted person will be serving time while he or she waits. And for a very long time.By the time they are acquitted, most have wasted their best years in conviction. If this isn't travesty of justice, what is? Here are some real cases. One Ayodhya was convicted by the Gonda district judge for dacoity and murder in 1982 and appealed promptly . He was finally acquitted in September this year after having been in jail for two years and 30 more years under the shadow of a wrongful conviction though out on bail. Getting employment or social acceptance in this period must have been next to impossible. Kanem Anjamma of East Godavari in Andhra was convicted in January 2010 along with her husband for murdering their neighbour G Nageswara Rao neighbour G Nageswara Rao in 2007. Locked up for over five years, Anjamma finally was acquitted by HC in June this year. Kavita Sharma and her alleged paramour, Krishna Kumar Sain, were arrested in 2004 for murdering Kavita's husband and convicted by the trial court in 2006. In July this year, the Rajasthan HC acquitted them. They had spent 11 years in jail.

The loss of their freedom apart, each of these people had to carry the stigma of being criminals and murderers and in most cases by the time the grinding wheels of justice spat out their final verdict, there really wasn't much of a life to return to. That these are not isolated cases, but are illustrative of a deep malaise, is evident from the statistics on pendency of cases. The adage about justice delayed being justice denied has never been truer or more powerfully brought home.

(With bureau inputs from states)

The Times of India’s View The Times of India, Oct 15 2015

The provision of justice is among the most basic of services the state is expected to render to its citizens. The data here makes it abundantly clear that the Indian state has failed miserably in discharging this duty. At a time when all reasoned opinion says India needs more judges at every level than it currently has, how can the state escape the responsibility for vacancies of the order of about 20% in the Supreme Court, 30% in the high courts and nearly 22% in the lower courts?

Almost every week, there's a report in this paper of someone being found innocent by the courts -but only after he she has spent years and years in jail. This Sunday, we carried a report of the Bombay HC declaring a person not guilty of murder -14 years after he had been thrown behind bars, eight of them while his appeal was pending. In many such long-pending cases, the defendants are abjectly poor and cannot afford bail, forget a decent lawyer. Some of them don't even come to trial for years though theirs are relatively minor infractions of the law such as pickpocketing; it's not uncommon for undertrials to spend more time in jail than the maximum term they would have got if convicted. It's almost as if these people are forgotten once they're thrown behind bars.

Since it is the state's negligence that is largely responsible for such delays, it is only fair it compensates those found to have been wrongfully confined if their appeal has taken more than a stipulated time to decide or the appeals court holds that the earlier conviction was a case of very poor judicial judgement. It cannot undo the years of freedom they've lost, or the damage to their reputation, but it can bring some support to those who've lost years of their working lives in jail. At the very least, it should pay Rs 50 lakh for every year lost, to someone who had no income. For those with modest incomes the amount should be Rs 1 crore per year, Rs 3 crore per year for those with middling incomes and Rs 7 crore-Rs 10 crore per year for those in higher income brackets. These sums may appear high, but remember they include both compensation for irreparable harm and an element of deterrence for wrongful confinement or tardy administration of justice.

There should be fast-tracking of appeals, at least in cases like the Aarushi murder. Someone might legitimately ask why the Talwars should receive `preferential treatment'. It is possible that in many other cases waiting to be heard, the collection of evidence and police investigation was shockingly slipshod -as in the Aarushi case -and due process of law not followed. So why should the Talwars not have to wait like everybody else? It's because they've been convicted of murdering their daughter in a case where the unanswered questions are too glaring and too many to ignore. There can be no fate worse than that of parents who may have been wrongfully convicted of their child's murder.First, the grief of losing a child in gruesome circumstances, and then being viewed as murderers by the world. An expeditious hearing is all they seek -and it should be granted.

In the end, the entire system needs to be fixed, and soon.How many years more will we let countless thousands rot in jail -away from home and family -for crimes they haven't committed? More than these people, it is the state and the criminal justice system on trial here.

2016: States with best and best disposal and causes

The Times of India, Jun 20 2016

Pradeep Thakur

Shortage of judges may not be the predominant factor behind the large pendency of cases in courts across the country as much as their efficiency, says a study commissioned by the law ministry after the Chief Justice of India recently attributed over three crore pending cases to a huge gap in the judge-population ratio. The CJI had sought 70,000 more judges to clear the backlog. The study , which compiled data between 2005 and 2015, lists several states with higher judge-population ratio -such as Delhi (47 judges per million population) and Gujarat (32 judges) -which are still struggling to dispose of cases.

Conversely , states such as Tamil Nadu (14 judges per million population) and Punjab (24 judges) have among the lowest pendency rates, according to the study. The findings also show a huge variation in the av erage number of cases disposed by a judge in a year in different states. In Kerala and Tripura, for instance, the rate of disposal per judge is as high as over 3,000 and 2,800 cases respectively per year while in states such as Jharkhand and Bihar, it is merely 255 and 274 cases respectively as per the working strength. India has an average 17 judges per million population on the current sanctioned strength, though there are over 44% vacancies in 24 high courts and 23% in subordinate judiciary . The current sanctioned strength of the subordinate judiciary is 20,214 judges while that of the 24 high courts is 1,056. The pendency of cases has remained abnormally high at 3.10 crore, as per the last estimates.

“There is no direct relation between judge-popula tion ratio and the pending cases,“ said the study , pointing out how states such as Tamil Nadu and Punjab which ranked lower in terms of judge-population ratio also ranked lower in terms of the number of pending cases.

The highest pendency of cases per million population are in the states of Delhi, Gujarat, Chandigarh, Tripura, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Jharkhand and Bihar--all having judge-population ratio above the national average of 17. The top five states have a judge-population ratio in the range of 20 to 47 judges per million population, but still have one of the highest pendency of cases per million population.

Quoting from a previous Law Commission report, the law ministry study said the judge-population ratio was a poor substitute for sound scientific analysis to arrive at the real reasons behind huge pendency.

Allahabad HC has highest pendency

Pradeep Thakur, Vacancies in judiciary, police force plague UP, March 27, 2017: The Times of India

New Delhi: The Aditya Nath Yogi government has resolved to improve the law and order situation in Uttar Pradesh but two important pillars of the justice delivery system -the police and the judiciary -are in a dilapidated condition in the state. There is over 47% vacancy of judges in Allahabad high court and more than 55% vacancy in the sanctioned strength of the police force in the state.

Allahabad HC, the country's largest with a sanctioned strength of 160 judges, continues to reel under severe manpower crunch. Former chief justice of the HC Justice D Y Chandrachud, before he was elevated to the Supreme Court in May last year, had recommended candidates to fill up almost 90% of these vacancies, but to no avail.

The recommendation got entangled in the standoff between the higher judiciary and the government over the process of appointment of judges. A year later, a majority of the recommendations for Allahabad HC are still pending approval of the government. Allahabad HC, short of 75 judges, has the highest vacancy among all HCs in the country .

Consequently , the HC has the highest number of pending cases as well, a significant number of which have been pending for more than five years and some for longer than 10 years. According to the last estimate, the total pending cases in Allahabad HC was 9.25 lakh, which is over 23% of 40 lakh cases pending in all 24 HCs in the country .

Now, with the BJP assuming power in the state and also being at the helm at the Centre, it is expected that these vacancies will be filled up fast.

A risk assessment carried out on Uttar Pradesh's rising crime graph by the CAG last year had found that UP was at the top among states having highest number of violent crimes, accounting for almost 13% of all such incidents. It also had the maximum cases of crime against women. “Shortage of about 55% of the police manpower, if not immediately addressed, may further worsen the crime scenario in the state,“ the CAG had warned.

Pendency of cases in District courts, region-wise, January 2017

The new year began with a crushing backlog in district courts, with over 2.3 crore cases pending across India as on January 2. Of these, approximately 1.5 crore are criminal cases, and 72 lakh, civil.

The data, compiled by the National Judicial Data Grid, comprises statistics of the district judiciary of the country , but excludes figures from family courts and courts where connectivity is not available.

With 55 lakh cases, 41 lakh criminal and over 13 lakh civil, Uttar Pradesh has the highest pendency . Cases not disposed of for over a decade constitute over 13% (over 7 lakh) of the state's total, with nearly 20 lakh cases, 36%, pending for less than two years.

Maharashtra ranks second, with 31 lakh cases pending in the state's district courts on January 2, including 20 lakh criminal and over 11 lakh civil cases. Of the state's total, 8% or over 2.5 lakh have been pending for over 10 years, and 45% or 14.6 lakh for less than two years.

The data also shows that nationally , cases pending for over 10 years comprise 10% of the total at 23 lakh, while those pending between two and five years constitute 30%.

The majority of the cases -over one crore, around 43% -have been pending for less than two years. Nationwide, the number of pending cases filed by senior citizens form 3.5% of the total. Nearly 23 lakh of the pending cases were filed by women.

Madhya Pradesh and Delhi have recorded a low pendency at approximately 4.6 lakh and 5 lakh, respectively . Only 1% of Delhi's total -comprising 3.4 lakh criminal and 1.6 lakh civil cases -have been pending for over a decade.

Tamil Nadu's district courts have 9 lakh pending cases, but it departs from the nationwide trend in that it has more civil than criminal cases.

The loss that delays inflict

Compensating for lost years

The Times of India, Oct 15 2015

In most developed countries, a wrongful conviction can lead to the aggrieved person seeking huge compensations. The reason is despite their proven innocence, those convicted find the odds of relocating themselves in society difficult. It's for this that such countries claim an obligation to facilitate financial compensation to the wrongfully convicted.

In our country, the only reward for wrongful conviction is release from prison, never mind if the life of that person has been destroyed after years and sometimes decades in prison, for no fault of theirs.

TOI looks at the state of justice -rather its miscarriage -that is unwittingly functioning towards a more criminalized society than a `humanistic' one. The old aphorism, “Let justice be done though the heavens fall,“ is turned on its head in our country, where the heavens fall on countless innocents who await the assistance of a system that wrongfully convicted them.

Ample vacations

Efforts to cut SC holidaysstalled

The Times of India, May 18 2016

Judges, advocates stalled efforts to cut SC holidays, say ex-CJIs

Dhananjay Mahapatra

As the Supreme Court commences its 48-day summer vacation, many former Chief Justices of India said their efforts to reduce pendency by shrinking the holidays were frustrated by both judges and advocates.

Just a few weeks back, CJI T S Thakur had become emotional while appealing to the government to speed up the appointment of judges to high courts as the huge pendency of nearly 40 lakh cases in HCs cast an enormous burden on judges.

Former CJIs feel reduction in holidays would be a major step to counter pendency . The 1966 rules of the SC had allowed it to take a summer break up to 10 weeks. The first reduction in the recess happened under then CJI Y K Sabharwal, who cut it down to eight weeks.

Many succeeding CJIs, including Justices S H Kapadia, P Sathasivam, R M Lodha and H L Dattu, tried to convince judges and the bar association to trim the break.“But the judges and advocates stonewalled any proposal for reducing the break. No doubt the summer is harsh in Delhi. But all others work during the summer. So why not judges,“ said an ex-CJI.

It was Lodha who wanted courts, including the SC, to function 365 days a year and had presented a blueprint for it. He had proposed that every judge would intimate in advance the major periods of leave he would take in a year and that would be incorporated to chart out a roster for sitting of judges without the SC closing for a day. During Lodha's tenure as CJI, the 1966 rules were amended and the summer break was officially reduced from 10 weeks to seven. “It would be ideal to reduce the summer break to four weeks,“ some ex-CJIs told TOI.

“The SC closes for two weeks for the winter break.It also closes for 10 days each for Holi, Dussehra and Diwali. The winter break could be reduced to a week and Holi, Dussehra and Diwali could each have three days holiday ,“ they said.

If the suggestions are taken and implemented, it will produce an additional 50 working days for the SC, the ex-CJIs said. In a year, at present, the SC works for 193 days, the HCs 210 days and trial courts 245 days.

Undertrials

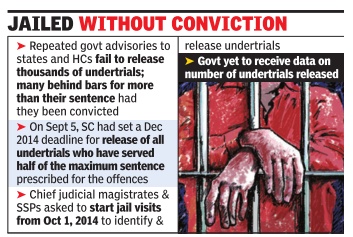

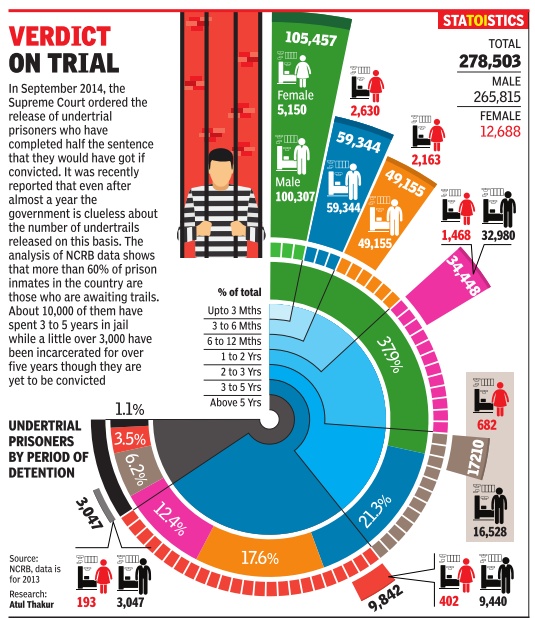

Undertrials, pending

May 08 2015

Pradeep Thakur