Jhansi District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Jhansi District

Physical aspects

South-western District of the Allahabad Division, United Provinces, lying between 24 degree 11' and 25 degree 50' N. and 78 degree 10' and 79 degree 25' E., with an area of 3,628 square miles. The District consists of two portions, each roughly shaped like a pear, which are connected by a narrow strip of country. The northern portion lies east and west, and is bounded on the north by the States of Gwalior and Samthar and by Jalaun District ; on the east by the Dhasan river, which separates it from Hamirpur and from portions of the smaller Bundel- khand States ; on the south by the State of Orchha ; and on the west by the States of DatiS, Gwalior, and Khaniadhana.

The southern boun- dary is extremely irregular, incorporating several enclaves of Native terri- tory, while British villages are also enclosed in the adjacent States. The southern portion, which lies north and south, is bounded on the west by the BetwS river, which separates it from Gwalior ; on the south by the Saugor District of the Central Provinces ; and on the east by the Dhasan and Jamni rivers, which divide it from the Bundelkhand States. The District presents a great variety in its physical aspects, and includes some of the most beautiful aspects scenery in the Provinces. The highest ground is in the extreme south, which extends to the two outer scarps of the Vin- dhyan plateau, running from the Betwa in a south-easterly direction and gradually breaking up into a confused mass of hills, parts of which approach a height of 2,000 feet above sea-level. Below the second scarp an undulating plain of black soil, interspersed with scattered hills and scored by numerous drainage channels, stretches north beyond the town of Lalitpur, and gradually becomes more rocky.

Low red hills of gneiss then appear, with long ridges running from south-west to north- east. These continue in the northern portion of the District, especi- ally east of the Betwa, but gradually sink into another plain of dark soil. The slope of the country is from south-west to north-east, and the rivers flow generally in the same direction. The Betwa is the most considerable river, and after forming the western boundary of the southern portion divides it from the northern half, which it then crosses. Its principal tributaries, the JamnI and Dhasan, form the eastern boundaries of the southern and northern parts of the District The Pahuj is a small stream west of the Betwa.

A striking feature of the DhasSn and of the Betwa, especially on the left bank, is the labyrinth of wild deep ravines, sometimes stretching 2 or 3 miles away from the river. The numerous artificial lakes formed by embanking valleys add to the natural beauty of the scenery. The largest are at Talbahat, Barwa SSgar, Arjar, Pachwara, and Magarwara.

The oldest rock is gneiss, which occupies the greater part of the Dis- trict. It forms the massive granitic ridges described above, which are traversed by gigantic quartz reefs, and often crossed at right angles by basic dikes of dolerite or diabase. South of Lalitpur the Upper Vindhyan massive sandstones, with a bed of Kaimur conglomerate near the base, rest directly on the gneiss, but in places the Bijawar and Lower Vindhyan series intervene. The former of these includes sandstones, limestones, and slates, some of the beds containing a rich hematitic ore, while copper has been found in small quantities. The Lower Vin- dhyans consist principally of sandstone and shale.

The fringe of the great spread of basalt constituting the Malwa trap just reaches the extreme south-east of the District, while a few outlying patches are found farther north, and the cretaceous sandstones of the Lameta group, which often underlie the trap, are met near the basalt’.

The flora of the District resembles that of Central India. A con- siderable area is ' reserved ' or ' protected’ forest, which will be described later; but there is a serious deficiency of timber trees, and the general appearance is that of low scrub jungle. Grazing is abundant, except in unusually dry years.

In the more level portion of the District, hog, antelope, and mlgai&o great damage to the crops. Leopards, chital, sdmbar, hyenas, wolves, and occasionally a lynx are found in the northern hills, while farther south tigers, bears, wild dogs, and the four-homed antelope are met with, and at rare intervals a wild buffalo is seen. Bustard, partridge, sand-grouse, quail, and plover are the commonest game-birds, while snipe, duck, and geese haunt the marshy places and lakes in the cold season. Mahseer and other kinds of fish abound in the larger rivers.

The climate of the District is hot and very dry, as there is little shade and the radiation from bare rocks and arid wastes is excessive. It is, 1 H. B. Medlicott, Memoirs, Geological Survey of India, vol. ii, pt. i. however, not unhealthy, except in the autumn ; and during the rains and short cold season the climate is far from unpleasant. In the south, owing to its greater elevation, the temperature is slightly lower than in the northern part

The annual rainfall averages about 31 inches, ranging from 34 inches in the north-west to about 41 in the south-east. In 1868-9 the fall amounted to only 15 inches, but in 1894-5 it was nearly 60 inches. The seasonable distribution of the rain is, however, of more importance than large variations in the total amount. Disastrous hailstorms are common in the cold season, and nearly 100 head of cattle were killed in a single storm in 1895.

History

Jhansi forms part of the tract known as British Bundelkhand, and its history is that of the Chandel and Bundela dynasties which once ruled that area. The earliest traditions point to the occupation of the northern portion by Parihar and Kathi Rajputs, and of the south by Gonds. The Chandels of Mahoba rose into power east of this District in the ninth century, but extended their power over it in the eleventh century, and have left many memorials of their rule in temples and ornamental tanks. After the defeat of the last great Chandel Raja by Prithwl Raj in 1182, and the raids of the Muhammadans under Kutb-ud-dln in 1202-3 and Altamsh in 1234, the country relapsed into anarchy.

The Khangars, an abo- riginal tribe, who are said to have been the servants of the Chandels and are now represented by a menial caste, held the tract for sometime and built the fort of Karar, which stands just outside the British border in the Orchha State. The Bundelas rose to power in the thirteenth or fourteenth century and expelled the Khangars. One of their chiefs, named Rudra Pratap, was recognized by Babar, and his son, Bharti Chand, founded the city of Orchha in 153 1. The Bundela power gradually extended over the whole of this District and the adjacent territory, and the authority of the Mughals was directly challenged. In the early part of the seventeenth century the Orchha State was ruled by Blr Singh Deo, who built the fort at Jhansi. He incurred the heavy displeasure of Akbar by the murder of Abul Fazl, the emperor's favourite minister and historian, at the instigation of prince Sallm, after- wards the emperor Jahangir.

A force was accordingly sent against him, which was defeated in 1602. On the accession of Jahangir in 1605, Blr Singh was pardoned and rose to great favour; but when, on the death of the emperor in 1627, Shah Jahan mounted the throne, Blr Singh revolted again. The rebellion was unsuccessful, and Blr Singh died shortly after. The south x of the District had already fallen into the. hands of another descendant of Rudra Pratap, who founded the State of Chanderl. In the latter half of the seventeenth century a third Bundela State was founded east of the District by Champat Rai, whose son, Chhatarsal, extended his authority over part of Jhansi. On his death, about 1734, the Marathas obtained the greater part of the District under his will, and in 1742 forcibly extorted most of the remainder from the Raja of Orchha. Jhansi remained under the Pesh- was for some thirty years, though in the south the Rajas of Chanderi still maintained partial independence.

After that period the Maratha

governors of the north of the District made themselves independent in

all but name. In 181 7 the Peshwa ceded to the East India Company

his sovereign rights over the whole of Bundelkhand, and in the same

year Government recognized the hereditary title of the Maratha

governor and his descendants to their existing possessions. The title

of Raja was granted to the Jhansi house in 1832 for services rendered

in connexion with the siege of Bharatpur. In 1839 the Political Agent

in Bundelkhand was obliged to assume the administration in the

interests of civil order, pending the decision of a dispute as to succes-

sion ; and the management was not restored till 1842, when most of the

District was entrusted to Raja Gangadhar Rao. The Raja died child-

less in 1853, when his territories lapsed to the British Government and

were formed into a District of Jhansi. Meanwhile the Chanderi State,

which comprised the south of the District and some territory west of

the Betwa, had also been acquired. A dissolute and inefficient ruler,

named Mur Pahlad, who had succeeded in 1802, was unable to control

his vassal Thakurs, who made constant plundering expeditions into the

neighbouring territory.

In 181 1 their incursions on the villages of

Gwalior provoked Sindhia to measures of retaliation, and Mur Pahlad

was deposed, but received a grant of thirty-one villages. In 1829

another revolt was headed by the former Raja. It was promptly sup-

pressed, and the State was divided, Mur Pahlad receiving one-third.

In 1844, after the battle of Maharajpur, Sindhia ceded to the British

Government all his share of the Chanderi State as a guarantee for the

maintenance of the Gwalior Contingent. The territory so acquired was

constituted a District called Chanderi, with the stipulation that the

sovereignty of the Raja and the rights of the inhabitants should be

respected.

In 1857 there was considerable discontent in both the Jhansi and Chanderi Districts. The widow of Gangadhar Rao was aggrieved, because she was not allowed to adopt an heir, and because the slaughter of cattle was permitted in Jhansi territory. Mardan Singh, the Raja of Banpur, had for some time resented the withholding of certain honours. The events of 1857 accordingly found the whole District ripe for rebellion. On June 5 a few men of the 12th Native Infantry seized a small fort in the cantonment containing the treasure and magazine. Many European officers were shot the same day. The remainder, who had taken refuge in the main fort, capitulated a few days after and were massacred with their families, to the number of 66 persons, in spite of a promise of protection sworn on the Koran and Ganges water. The Rani then attempted to seize the supreme authority; but the usual anarchic quarrels arose between the rebels, and the whole country was plundered by the Orchha leaders. The Bundelas also rose in the south ; and Lalitpur, the head-quarters of the ChanderT District, was abandoned by the British officials, who suffered great hardships, but. were not murdered. The Raja then asserted complete independence and extended his rule into parts of Saugor District, but was driven back to Chanderl by Sir Hugh Rose in January, 1858. On March 3 the British army forced the passes in the south of the District and marched north. Jhansi was reached on March 20, and during the siege Tantia Topi, who attempted a diversion, was completely defeated.

The town was assaulted on April 3, and

the fort was captured on the 5th. Sir Hugh Rose had been compelled

to march forward to Jalaun District, leaving only a few troops at Jhansi,

and disturbances soon broke out again, and increased when news of

the Gwalior revolution was received. The Maratha chief of Gursarai,

in the north of the District, held out for the British, and in July the

Banpur Raja gave himself up. The south and the west of the District,

however, were not cleared till late in the year. In 1861 the name

of the Chanderl District was changed to Lalitpur ; and in the same year

the portions of that District west of the Betwa, together with Jhansi

town and fort, were ceded to Sindhia. In 1886 Jhansi town and

fort, with 58 villages, were made over to the British by Sindhia in

exchange for the Gwalior fort, Morar cantonment, and some other

villages. The two Districts of Jhansi and Lalitpur were united in

1 89 1 ; but the area included in the latter forms an administrative

subdivision.

Population

The District is exceptionally rich in archaeological remains. Chandel memorials in the form of temples and other buildings are found in many places, among which may be mentioned Chandpur, Deogarh, Dudhai, Lalitpur, Madanpur, and Siron. At Erachh (Irich) the fragments of ancient buildings have been used in the construction of a fine mosque, which dates from 141 2.

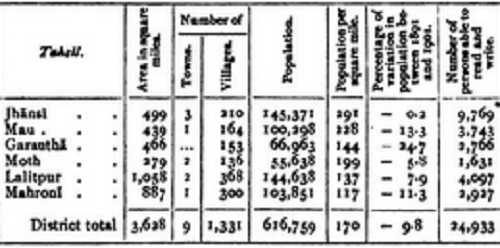

Jhansi District contains 9 towns and 1,331 villages. Population had been increasing steadily for some time, but received a check in the series of bad years between 1891 and 1901. The -

numbers at the last four enumerations were as follows : (1872) 530,487, (1881) 624,953, (1891) 683,619, and (1901) 616,759. There are six tah&ls — Jhansi, Mau, Garautha, Moth, Lalitpur, and Mahroni — the headquarters of each being at a place of the same name. The principal towns are the municipalities of Jhansi, the administrative head-quarters of the District, Mau-Ranipur, and Lalit- pur. The following table gives the chief statistics of population in 1901 : —

Nearly 93 per cent, of the population are Hindus and only 5 per

cent. Muhammadans. Jains number 10,760, forming 1-7 per-cent. of

the total — a higher proportion than in any other District of the United

Provinces. The density of population is lower than in any part of the

United Provinces, except the Kumaun Division, and the District suffered

heavily from famine in 1895-7 and again in 1900. More than 99 per

cent, of the people speak Western Hindi, chiefly of the Bundeli dialect.

Chamars (leather-dressers and cultivators), 76,000, are the most numerous Hindu caste, followed by Kachhis (cultivators), 58,000; Brahmans, 58,000; Ahirs (graziers and cultivators), 52,000; Lodhas (agriculturists), 47,000 ; and Rajputs, 35,000. Among castes peculiar to this part of India may be mentioned the Khangars (9,000), Basors (9,000), and Saharias (7,000) ; the two former being menials, and the last a jungle tribe. Shaikhs (13,000) are the most important Musal- man tribe. About 56 per cent, of the total population are supported by agriculture and 8 per cent by general labour. Rajputs, Brahmans, Ahlrs, Lodhas, and Kurmls are the chief proprietary castes, the first named being largely of the Bundela clan.

In 1901 there were 777 native Christians, of whom 355 belonged to the Anglican communion and 267 were Roman Catholics. The Church Missionary Society has had a station at Jhansi since 1858, and the American Presbyterian Mission since 1886.

Agriculture

The characteristic feature of Jhansi, as of all the Bundelkhand Districts, is its liability to alternate cycles of agricultural prosperity and depression. It contains the usual soils found in this tract. Mar and kabar are dark soils, the former being distinguished by its fertility and power of retaining moisture, while kabar is less fertile, becomes too sticky to plough when wet, and dries very quickly, spliting into hard blocks.

Parwa is a brownish or yellowish soil more nearly resembling the loam of the Doab. Mar 9 the commonest variety, covers a large area in the centre of both the northern and southern portions of the District, and is also found on the terraces of the Vindhyas. It produces excellent wheat in favourable seasons, but is liable to be thrown out of cultivation by the growth of kdns (Saecharum spontaneutn). This is a tall thin grass which quickly spreads when tillage is relaxed; its roots reach a depth of 6 or 7 feet, and finally prevent the passage of the plough. After a period of ten or fifteen years kdns gradually gives way to other grasses, and the land can again be cultivated. In the neck of land which connects the two portions of the District, and for some distance south of the narrowest point, a red soil called rakar patri is found, which usually produces only an inferior millet. Interspersed among these tracts of poor soils little oases are found, generally near village sites and in valleys, which are carefully manured and regularly watered from wells sunk in the rock. The spring crops are peculiarly liable to attacks of rust in damp, cloudy weather. Along the rivers there is a little alluvial land, and near the lakes in some parts of the District rice can be grown. In the north-west, field embankments are commonly made, which hold up water for rice cultivation and also serve to stop the spread of kans.

The greater part of the land is held on the usual tenures found in the United Provinces. In the Lalitpur subdivision nearly two-thirds of the whole area is included in zamindari estates, while patftddri holdings are commoner in the rest of the Djstrict. A peculiar tenure, called ubdtiy is also found. This originated from grants of land given in lieu of a definite annual sum, or hakk. Where the annual value of the land granted exceeded the hakk, the excess (uddri) was paid as revenue. The tenure is thus equivalent to an abatement of the full revenue chargeable.

Some of the ubdti tenures, called batota % date

from the occupation of Chanderl by Sindhia and are not liable to

resumption; but the others, which were mainly granted after the

British occupation, are liable to be resumed for misconduct, on the

death of an incumbent (though such resumptions are rare), or if any

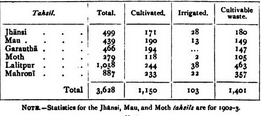

part of the ubdri estate is transferred. The main agricultural statistics

for 1903-4 are given below, in square miles : —

Jowar covered 326 square miles, kodon and other small millets 223, and gram 196. Wheat follows in importance with 89 square miles, and barley, rice, maize, and bdjra are the remaining food-crops. Oil- seeds were grown on 206, and cotton on 46 square miles.

The methods of cultivation in Bundelkhand are conspicuously poor, and the people easily yield to adverse circumstances. There has thus been no improvement in agricultural practice since the commencement of British rule. Within the last twenty years considerable loss has been caused by the introduction of artificial dyes in place of al (Morinda citrifolid). The al plant was grown on the best land, and required careful cultivation, which is the best preventive of a spread of kans. The losses incurred by blight in 1893 and 1894 have also led to the replacement of wheat by the less valuable gram, but there has been a slight recovery.

The steps taken to extend irrigation will be described later. Advances under the Land Improvement and Agriculturists' Loans Acts are freely taken, especially in bad seasons. A total of nearly 3 lakhs was advanced during the ten years ending 1900, and Rs. 60,006 in the next four years.

The cattle are smaller and hardier than in the Doab, but the best animals are imported from the neighbourhood of the Ken river or from Gwalior. Attempts were made to improve the breed about 1870; but the Nagor and Hissfir bulls which were imported were too large and too delicate. There is no horse-breeding in the District, and the ponies are of a very poor type. Donkeys are extensively used as beasts of burden. The sheep are of the ordinary inferior kind ; but the goats bred along the banks of the Dhasan are celebrated for their size and the quantity of milk which they give.

In years of well-distributed rainfall, mar and kabar require no arti- ficial sources of irrigation. Thus in 1903-4 only 103 square miles were irrigated in the whole District. Wells supplied 91 square miles, tanks 7, and canals 3. The well-irrigation is chiefly found in the red- soil tracts of the Jhansi tahsil and the northern part of the Lalitpur subdivision. Tanks are very numerous, and the embankments of about thirty are maintained by the Public Works department, with 38 miles of small distributaries. New projects for making tanks are being carried out, and these serve a useful purpose by maintaining a high water-level, even where they are not used for irrigation directly. Much has already been done in repairing old embankments and in deepening lakes and improving the irrigation channels. A canal is taken from the Betwa at Parichha, where the river is dammed ; but it irrigates a very small area in Jhansi, chiefly serving Jalaun. A second dam is under construction higher up at Dukwa, which will impound a further supply. Water from wells is usually raised by means of the Persian wheel Government forests cover 189 square miles, of which 141 are situ- ated in the Lalitpur subdivision.

There is also a large area of private forest The ' reserved ' forests produce little timber ; but they supply the wants of the villages in the neighbourhood, as well as some quantity of bamboos for export, and are of value for climatic reasons. Grass is especially important; and minor products, such as honey, lac, gum, catechu, and various fruits and roots, are also gathered by the jungle tribes. The chief trees include several kinds of acacia, Adina cordi- folia y Anogeissus latifolia, Diospyros melanoxylon, Grewia vestita, various figs, Lagcrstroemia parvjflora, teak, and Tertninalia tomcntosa. The mahua (Bassia latifolid) grows well. During years of famine the forests are thrown open to grazing, and also supply roots and berries, which are eaten by the jungle tribes.

The most valuable mineral product is building stone, which is quar- ried from the Upper Vindhyan sandstone, and exported. Steatite is worked in one place, and iron is smelted after indigenous methods in a few small furnaces. The roads are largely metalled with disin- tegrated gneiss.

Trade and communication

Coarse cotton cloth, called khdrud, is still woven at a number of places; and at Erachh more ornamental articles, such as chintz and large kerchiefs dyed with spots, are turned out. Small woollen rugs are made at Jhansi, and some good silk is woven at the same place. Mau, Jhansi, and Maraura are noted for brass work. The railway workshops at Jhansi city employed 2,169 bands in 1903, and there are a small cotton- gin and an ice factory.

The most valuable exports of the District are oilseeds, ghi, and pan. Grass, minor forest products, and road metal are also exported, and hay was baled in large quantities for the Military Department during the Tirali expedition of 1895 and the South African War. There is no surplus of grain, except in very prosperous years. Sugar, salt, kerosene oil, and grain are the chief imports.

Jhansi city, Mau-Ranlpur, Lalit- pur, and Chlrgaon are the principal trade centres, and Cawnpore and Bombay absorb most of the trade. There is, however, a considerable amount of local traffic with the adjacent Native States, and also some through trade.

Jhansi city has become an important railway centre. The main line of the Indian Midland Railway (now amalgamated with the Great Indian Peninsula) enters the south of the District, and divides into two branches at Jhansi, one running north-west to Agra and the other north-east to Cawnpore. A branch line from Jhansi crosses the south- east of the northern division of the District.

There are 1,295 miles of roads, a greater length than in any other District of the United Pro- vinces. Of the total, 340 miles are metalled and are maintained by the Public Works department, but the cost of 160 miles is charged to Local funds. There are avenues of trees along 364 miles. The principal routes are : the road from Cawnpore to Saugor through Jhansi and Lalit- pur, which traverses the District from end to end ; and the roads from Jhansi to Gwalior on the north-west, and to Nowgong on the south-east.

Famine

The District is specially exposed to blights, droughts, floods, hail- storms, and their natural consequence, famine, which is generally . accompanied by disastrous epidemics of fever and

cholera. No details are known of the famines which must have periodically devastated this tract ; but it is commonly said that famine may be expected in Bundelkhand every fifth year. The first serious famine after the Mutiny occurred in 1868-9, and it was probably the worst in the century.

The rains of 1868 ceased pre- maturely and the autumn harvest was almost a complete failure. Poor- houses were opened, and subsequently relief works were started, which took the form of roads, bridges, and irrigation embankments in Jh&nsi District, and the excavation of tanks and construction of embankments in Lalitpur.

The total expenditure on this form of relief was nearly 3 lakhs, and the number of workers at one time rose above 26,000. Epidemics of small-pox and cholera followed ; and the climax came when the rains of 1869 broke, and the roads, which were at that time unmetalled, became impassable. Excluding several partial losses of the harvest, the next great famine took place in 1896-7. Since the autumn of 1893 the autumn crops had been poor, and the spring crops even poorer, while kans had spread rapidly.

The rains of 1895 were deficient, and relief works were opened in February, 1896. In May 42,000 persons were being relieved, and a terrible epidemic of cholera added to the loss of life. The works were almost abandoned by the middle of July, and up to the end of August prospects were fair. The monsoon, however, ceased abruptly, prices rose with alarming rapidity, and the relief works had to be reopened.

The autumn was also marked by a virulent epidemic of fever, which attacked even the well- to-do. The distress became most acute in May, 1897, when nearly 100,000 persons were being relieved. Large suspensions and remis- sions of revenue were made, and relief works were closed in Sep- tember, 1897. In 1899 a short rainfall again caused great distress in the red soil area, and the effects were increased by the high prices due to famine in Western India.

Administration

The tahsil of Lalitpur and MahronI form the subdivision of Lalit- pur, which is in charge of a member of the Indian Civil Service, assisted by a Deputy-Collector. The ordinary Dis- trict staff consists of the Collector, a Joint-Magistrate, and three Deputy-Collectors recruited in India. The Forest officer is in charge of the whole of the Bundelkhand forest division.

There are two District Munsifs, and a Sub-Judge for civil work. The District and Sessions Judge has jurisdiction over the neighbouring District of Jalaun, and a Special Judge is at present engaged in inquiries under the Bundelkhand Encumbered Estates Act The District is notorious for outbreaks of dacoity in bad times, and crimes of violence are not infrequent ; but generally speaking, crime is light.

Up to 1 89 1 the present Lalitpur subdivision formed a separate Dis- trict, and the fiscal history of the two portions of what is now the District of Jhansi is thus distinct. After the lapse of Jhansi in 1853 the three Districts of Jhansi, Chandeif (or Lalitpur), and Jalaun were placed in charge of Deputy-Superintendents, under a Superintendent who was subordinate to the Commissioner of the Saugor and Nerbudda Territories at Jubbulpore.

In 1858 these Districts (including Hamlrpur up to 1863) were detached from Jubbulpore and administered as a Division in the Province of Agra on the non-regulation system. Finally, in 1891, the Districts were included in the Allahabad Division and were brought under the ordinary laws, many of which had already been applied.

In Jhansi District proper the Mar&tha revenue system was ryotwdri, and the nominal demand was a rack rent, which could be paid only in very favourable seasons. Arrears were not, however, carried over from one year to another. The early settlements of those portions of the District which were acquired between 1842 and 1844 were of a sum- mary nature, and only for short periods. The first regular settlement of the whole commenced with a survey in 1854, but was interrupted by the Mutiny and not completed till 1864. Proprietary rights had been partly introduced between 1839 and 1842, and the sale of land by decree of the civil courts followed in 1862. The settlement, which was made by several officers on different principles, resulted in an assess- ment of 4-3 lakhs, as compared with a previous demand of 5-6 lakhs, in addition to about Rs. 50,000 due on account of ubdrls.

The demand was undoubtedly reasonable ; but the rigid system of collection and the freedom of sale of land were new ideas that were not grasped by the people. Some landowners had been in debt since the days of Maratha rule. After the Mutiny, revenue was collected from many from whom it had already been extorted by the Orchha or Jhansi rebels. In 1867 the crops failed, and in 1868-9 there was famine and great loss of cattle. In 1872 many cattle were again lost from murrain. Although the settlement had appeared light, it became necessary to re-examine the condition of the District in 1876. After much discus- sion the Jhansi Encumbered Estates Act (XVI of 1882) was passed, and a Special Judge appointed, who was empowered to examine claims and reduce excessive interest.

The sale of a whole estate operated as a discharge in bankruptcy to extinguish all debt due. Altogether, 1,475 applications were tried, and out of a total claim of i6-6 lakhs the Judge decreed 7-6 lakhs. More than 90 per cent, of the amount decreed was paid in full : namely, 12 ½ per cent, in cash, 46 per cent by loan from Government, and 32 per cent, by sale of land, only 9 ½ per cent being discharged under the insolvency clause. Many estates were cleared by sale of a portion only. A striking feature of the proceedings was the rapid rise in the value of land. The next revision of settlement was made between 1889 and 1892. This was carried out in the usual way by assessing on the actual rent-rolls, corrected where necessary by applying the rates ascertained for different classes of soil. The total revenue was raised from 4-9 to 5-5 lakhs.

In the Lalitpur District conditions were different, for zamindari rights existed, except where the Marathas had extinguished them. The early British settlements were of a summary nature, and for short periods ; and though nominally based on recorded rentals or customary rates, a system of auction to the highest bidder was sometimes followed, with disastrous results. The first regular settlement was commenced in 1853, but was interrupted by the Mutiny, and was not completed till 1869. The methods employed were a compromise between the valua- tion of villages by applying rates found to be paid for different classes of soil, and the valuation of the ‘ assets ' actually recorded. The result was a reduction from 1-8 to 1-5 lakhs. This settlement came under revision in 1896, and the revenue was raised to i-6 lakhs, though this was only to be reached by degrees, and the initial demand was 1-4 lakhs.

The revenue demand for the whole District was thus 7 lakhs when the famine of 1896-7 broke out. The special legislation of 1882 had only had a temporary effect, and the District has now been brought under the provisions of the Bundelkhand Encumbered Estates Act. The Land Alienation Act has also been applied, and transfers are restricted in the case of land held by agricultural tribes. Summary reductions of revenue brought down the demand to 6-3 lakhs in 1902-3, or less than 5 annas per acre, varying from 1 anna to nearly 12 annas in different parts. In 1903 a new settlement was commenced under the special system, by which the demand will be liable to revision every five years.

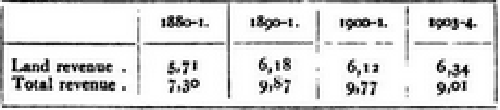

Collections on account of land revenue and total revenue have been, in thousands of rupees : —

There are three multiplities, and six towns are administration under

Act XX of 1856. Outside of these, local affairs are administered by the .District board, which had an income of 1-7 lakhs in 1903-4, chiefly derived from a grant from Provincial revenues. The expenditure included a lakh devoted to roads and buildings.

The District Superintendent of police has two Assistants, one of whom is posted to Lalitpur. The ordinary force, which is distributed in 39 police stations, includes 7 inspectors, 185 subordinate officers, and 784 men, besides 215 municipal and town police, and 1,528 rural and road police. A Superintendent of Railway Police also has his head- quarters at Jhansi city. The District jail contained a daily average of 267 prisoners in 1903.

Jhinsi takes a high place in regard to the literacy of its inhabitants, of whom 4 per cent. (7-7 males and 0-3 females) could read and write in 1901. The number of public schools fell from 98 in 1880-1 to 85 in 1900-1, but the number of pupils increased from 2,537 to 2,962. In 1903-4 there were 167 such schools with 5,982 pupils, of whom 146 were girls, besides 39 private schools with 529 pupils.

Two schools

are managed by Government and 133 by the District and municipal

boards. All the schools but two are primary. The total expenditure

on education in 1903-4 was Rs. 41,000, of which Local funds provided

Rs. 37,000, and fees Rs. 3,000.

There are 10 hospitals and dispensaries, with accommodation for 170 in-patients. About 62,000 cases were treated in 1903, including M83 in-patients, and 3,000 operations were performed. The total expenditure was Rs. 15,000, chiefly met from Local funds.

In 1903-4, 23,000 persons were successfully vaccinated, representing a proportion of 38 per 1,000 of population. Vaccination is com- pulsory only in the Jhansi cantonment and in the municipalities.

(District Gazetteer (1874, under revision); W. H. L. Impey and J. S. Meston, Settlement Report, excluding Lalitpur (1893); H. J. Hoare, Settlement Report, Lalitpur subdivision (1899) ; P. C. Mukherji, Antiquities in the Lalitpur District (1899) ; A. W. Pirn, Final Settlement Report, including Lalitpur (1907).]