Jago Hua Savera

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Crew

Director A.J. Kardar

Producer Noman Taseer

Writers:

Manik Bandopadhaya ... (novel)

Faiz Ahmed Faiz ... (screenplay)

Music Timir Baran

Cinematography Walter Lassally (UK)

Lyrics: Faiz Ahmed Faiz

Playback singing: Altaf Mahmud ...

Cast

Khan Ataur Rahman

Tripti Mitra

Kazi Khaliq

Zurain Rakshi )

Maina Latif

Nasima Khan

Moyna

Rizwan

Roxy

Technical specifications

Length 94 minutes

Country: then Pakistan, with some Indian artistes. The producer and director of the films were West Pakistanis, but the film was set in what is now Bangladesh.

Synopsis

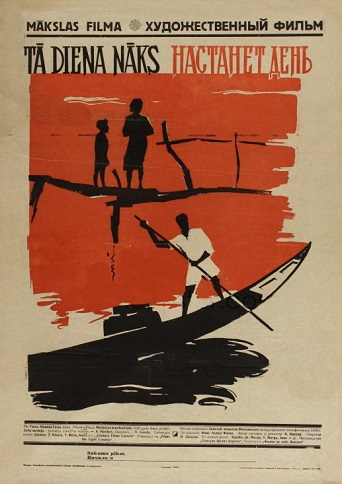

Jago Hua Savera (Day Shall Dawn) is the story of a section of the fishermen people of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), of their little human weaknesses and strengths... and, deep down, of their undaunted and undefeatable spirit.

By many standards, life in these far flung tiny villages is dull and monotonous, yet, for the people who live there, life is full of trials and turbulence.

This is the story of the people of the river to hunt for fish.

This is the story of one such man, of many such men, each aspiring to own their own boat.

Interesting facts about Jago Hua Savera

It was the film that reinvented Pakistani cinema. Jago Hua Savera (The Day Shall Dawn) by Aaejay Kardar transports us to a fishing village in the East of the country, where everyone dreams of owning their own boat. The film, which came out in 1958, is being honoured in a restored version in Cannes Classics

A film made on a shoestring…

Before turning to film, Aaejay Kardar's life revolved around the sea. He left the merchant navy to study film in London before making Jago Hua Savera, his first film. He brought together a very small team: a German cameraman, a British sound recorder and a Pakistani poet writing his first ever screenplay. Around a hundred people were auditioned for the twelve roles in the film, only one of whom had ever acted on camera.

…but now a landmark!

It was a huge risk but his efforts paid off. Jago Hua Savera met with worldwide critical acclaim, and was even pre-selected for the Best Foreign Film Oscar in 1960. The actors were turned into stars overnight. The film is seen as the first ever Pakistani melodrama – a genre that was more highly developed in neighbouring India.

A quasi-documentary fiction

In the 1950s, East Pakistan (today's Bangladesh) had no resources for filmmaking. Jago Hua Savera was consequently one of the first films to offer the world an insight into the region, the poverty of its fisherfolk and life far from the big cities, dominated by the rhythms of the river.

A presentation by the Nauman Taseer Foundation. Picture and sound restored by the Deluxe Restoration in London commissioned by Anjum Taseer based on the best available components, in the absence of the negative.

The Guardian on The Day Shall Dawn

This landmark film about Bengali fisherfolk fighting to survive in a world of hunger and loan sharks is finally getting its due

Row me away, boatman

I am but a cloud

Above a river of woes

All alone

In the dark night...

Without a homeland

I have lived forever in exile...

Soon our sorrows shall come to an end

Look, the day has dawned.

Sung sweetly over the melancholic tones of an Indian flute, these alternately bleak and hopeful lines encapsulate the condition of South Asia’s long-suffering rural proletariat. Penned by revolutionary poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz and paired with the exquisite cinematography of German-born British cameraman Walter Lassally, they make for a memorable opening to Pakistan’s first serious attempt at modernist cinematic realism: Day Shall Dawn (Jago Hua Savera).

Nearly six decades after its original release, AJ Kardar’s newly restored black and white feature about the everyday struggles of East Bengali fisherfolk was recently screened at Cannes. For a new generation of film-makers in Pakistan, the opportunity to review this early engagement with experimental cinema will provide welcome inspiration. Without a national film archive, much of Pakistan’s celluloid heritage has been lost or destroyed.

Pakistani cinema is assumed to have been untouched by the 20th century’s avant-garde film movements. But, with its documentary treatment of village life, labour and capitalist exploitation bearing recognisable traces of socialist realism, Italian neo-realism and Indian parallel cinema, Day Shall Dawn proves otherwise. The intimate involvement of revered poet Faiz – credited with story, lyrics and dialogue – adds gravitas to an already intriguing endeavour.

Faiz’s daughter Salima Hashmi, herself a renowned artist based in Lahore, describes viewing the film at Cannes as an emotional experience. Her father was prevented from attending the premiere at Wardour Street, London, having been jailed in an anti-communist crackdown by General Ayub Khan, who launched a coup shortly before the film was released. It won gold at the Moscow film festival in 1959, appearing briefly on screens before entering hibernation. With the military in power, Faiz went into exile, a pattern that would repeat itself after the coup of 1978. General Zia-ul-Haq’s fiercely conservative programme of Islamicisation and censorship hampered independent film-making throughout the 1980s.

Day Shall Dawn’s reappearance on the big screen has been brought about largely by Anjum Taseer, son of Nauman, the cultured businessman who produced and financially backed the film in its original incarnation. Fired by passions reminiscent of his father’s ambition, Anjum’s tenacious digging led to the re-emergence of prints from storage in France, London and Karachi. Thereafter, screenings at the Three Continents festival in Nantes in 2007 and New York in 2008 followed. In 2009, painstaking restoration was begun, “frame by frame”, says Taseer. “I’m doing it for Pakistan as much as my father.”

With a resurgence of cinemagoing in the country’s rapidly developing cities, perhaps Pakistan will greet the film with greater enthusiasm than it did in 1959. New digital productions such as Zinda Bhaag (2013), Pakistan’s first Oscar entry since Day Shall Dawn, have led to a revival in the national film industry’s fortunes after decades of involution.

And yet the importance of Kardar’s lone feature goes beyond Pakistan. Its cosmopolitan history of production reveals complicated patterns of artistic exchange that belie sharply drawn national or movement-based classifications. Cameraman Lassally played a key role in the transfer of visual ideas between Kardar’s tiny crew and the global independent cinema scene. He and soundman John Fletcher were closely associated with Britain’s influential Free Cinema series: a programme of BFI-funded experimental films (“free” of commercial pressures) presented to the public with a manifesto in 1956.

Kardar’s direction and Lassally’s use of the Arriflex to film a mostly amateur cast in non-studio settings along the banks of the river Meghna are clearly influenced by continental realism’s methods and Free Cinema’s preoccupation with quotidian life at the margins. The minimalist plot concerns a boatman’s aspirations for autonomy in a poverty-stricken world of hunger and exploitative loansharking; sizeable shot lengths result in decelerated narrative pace.

Another key reference point was Satyajit Ray, whose Pather Panchali had made waves following its release in 1955. Lindsay Anderson, Lassally’s friend and collaborator on the Free Cinema programme, exchanged letters and conversations with the Bengali master, who visited London in 1950. More directly, Ray’s assistant director Shanti Chatterji joined Kardar’s crew from Calcutta; Lassally’s haunting portrait of a gaunt elderly woman over the sounds of an ailing villager’s protracted coughing fit is testament to the influence of the Apu Trilogy.

Approaching 90, Lassally, whose Jewish ancestry meant he had to flee Berlin, the city of his birth, for London in the 1930s, recalls his friendship with Kardar fondly from Greece where he now lives. A straight-talking practitioner, he plays down the importance of Free Cinema and steers clear of labels like neo-realism. Just as well: south Asia’s embrace of cinematic modernism calls for more fluid, interactive terms of analysis.

Ray’s work is inspired as much by Jean Renoir’s influence as De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948), which impressed him greatly. A recently translated 1949 essay by the Pakistani literary critic Hasan Askari refers admiringly to Farrebique, a 1946 documentary about farm life in the Massif Central. Salima Hashmi describes Faiz as deeply inspired by Eisenstein. All of which suggests south Asian film critics and cineastes didn’t simply import western film styles wholesale – they borrowed across movements for their own purposes, melding global ideas with tradition. Day Shall Dawn features a (currently missing) “masala” courtesan dance shot in colour, performed to a lyrical rendition of Faiz’s poetic communist manifesto, No Messiah for Broken Shards. Dancer Rakshi travelled to London during post-production to advise on how to edit it.

London’s role as a hub of artistic exchange for south Asians and their global contemporaries is not surprising given Britain’s historic ties with the Commonwealth. But Day Shall Dawn bridges other east-west divides with equally bloody histories. Drawing on acting, musical, technical and literary talent from both of Pakistan’s then East and West wings in addition to West Bengal, Kardar’s film is a rare collaboration between artists and intellectuals in India, Pakistan and what would later become Bangladesh. For this very reason, it is unlikely to be claimed by officialdom in any of the three countries without hesitation.

Bangladesh might well view Day Shall Dawn, shot in the language of its former oppressor, with ambivalence. Thirteen years after the film was released, the East wing seceded after a war of independence that drew in India and flared into one of the 20th century’s worst genocides. The truncated Pakistani state has yet to confront its past, refusing to apologise for war crimes and failing to accept the violence was triggered by the West wing’s denial of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s democratic mandate to govern.

Curated sensitively, however, screenings of Day Shall Dawn could foster dialogue between pluralist, progressive forces within the two nations. Hashmi recalls Faiz tailoring his dialogue to employ, as much as possible, words common to Urdu, Hindi and Bengali. The plot and setting are inspired by Manik Bandopadhay’s 1930s novel, Padma River Boatman, an important work of Bengali modernist fiction. Proper acknowledgement of its contribution might trigger renewed interest in Bandopadhay’s formidable writings. With Faiz’s poetry, their pro-poor message of justice, solidarity and minimalist riverine aesthetics would not go amiss in today’s subcontinent of bombastic nationalism, chauvinistic religion and unbridled capitalism, oblivious to the impending challenges of climate change.

Two decades after shooting in East Bengal, Lassally returned to Pakistan to work on Jamil Dehlavi’s masterful Blood of Hussain, a political allegory about the tyranny of military dictatorship. Another coup on the eve of its completion saw it banned. The revolutionary “dawn” never came. Pakistan’s brief experience of socialism in the 1970s abruptly ended with the judicial murder of its first democratically elected civilian ruler (after Rahman), Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

Kardar went onto make a series of important documentaries about Pakistani painters such as Sadequain and Shakir Ali. Tantalisingly, these are thought to lie somewhere among his possessions, together with the missing colour sequence from Day Shall Dawn and at least two other collaborations with Faiz: a documentary on the poet philosopher Iqbal, and an uncut feature, Of Human Happiness. Purportedly a critique of clerical obscurantism, it was shot in Baluchistan – a province in which the Pakistani state’s intermittent military operations against separatists today eerily echo its heavy-handed responses to demands for justice from Dhaka in the lead up to the bloodbath of 1971.

- Jago Hua Savera was shown at SOAS University of London, 14 June 2016; and Filmhouse, Edinburgh, 28 June. Ali Nobil Ahmad is a fellow at the Zentrum Moderner Orient in Berlin. He is editor of Cinema in Muslim Societies and co-editor of Cinema and Society: Film and Social Change in Pakistan, both published this year.

Commercial failure, critical hit

CELLULOID MAGIC - Jago Hua Savera, a gem of a movie collaboration Oct 18 2016 : The Times of India

Imagine this. A rare neo-realist Pakistani feature film depicting the lives of struggling fishermen is lost to history. A desperate search over a decade results in the print being traced to France. The black-and-white film is in miserable condition; so it is digitally re-mastered and subtitled.

First released in 1959, `Jago Hua Savera' described recently by The Guardian as “Pakistan's first serious attempt at modernist cinematic realism“ is treasure for every serious movie buff. The film involved artistes from India, Pakistan and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Its screenplay and lyrics were written by Faiz Ahmed Faiz, among the greatest Urdu poets of revolution and desire. The songs were composed by Timir Baran, regarded the father of Indian symphony orchestra. The aching `Ab chhodo gham ki baat' and the consoling `Ghabrao mat majhi' are compositions fused with empathetic poetry . The female lead was played by the compelling Tripti Mitra, who was the wife of legendary theatre personality Sombhu Mitra.

Shot on the outskirts of Dhaka with Khan Ataur Rehman of East Pakistan playing the male lead, the film is loosely based on `Padma Nadir Majhi' written by Manik Bandopadhyay , one of the most distinctive voices in 20th century Bengali literature.

Another highlight is the evocative photography by British cinematographer Walter Lassally , who later won an Oscar for `Zorba the Greek' (1964). One scene shows a tired fisherman breathing hard, followed by a fish gasping for breath thus drawing parallels in their lives.

The film was directed by A J Kardar, brother of A R Kardar who gave hits like Dillagi (1949). Jago Hua Savera flopped when released in Pakistan but bagged gold medal at Moscow Film Festival.

Pakistan’s first Oscar submission ‘Jago Hua Savera’ goes to Cannes

Ali Raj, The Express Tribune May 1, 2016 Pakistan’s first Oscar submission ‘Jago Hua Savera’ goes to Cannes

Over 55 years after it became the newly-formed Pakistan’s first Oscar submission, AJ Kardar’s Jago Hua Savera (Day Shall Dawn) has been selected for screening at the prestigious Festival de Cannes 2016.

Part of the non-competitive Cannes Classics programme, Jago Hua Savera will join a line-up that also includes films made by Marlon Brando, Andreï Tarkovski and Jean-Luc Godard.

Talking to The Express Tribune, an official at the Festival de Cannes confirmed that this is the first time a Pakistani film has been inducted in Cannes Classics. Requesting anonymity, he said, “Cannes Classics is a section of the Festival de Cannes dedicated to restored prints, documentaries about cinema, tributes and cinema materclasses.” When asked on what basis was Jago Hua Savera shortlisted, he added, “We never comment on the selection. The fact that the film has been selected speaks for itself. We receive submissions from all over the world; films belonging to the history of cinema and those that have been technically restored.”

Back from the dead

The film’s original negatives were all lost and the restoration was carried out through various rolls of 35mm black and white prints. This tedious task was taken up by the progeny of Nauman Taseer, the late producer of the film. His son Anjum Taseer explained the restoration process, “The element was carefully scanned. Pre-grading on Nucoda optimised the tone scale followed by semi-automated passes through Phoenix for stabilisation and removal of defects. Extensive manual cleaning, using MTI Nova, Diamant and Phoenix softwares, restored the images as closely as possible to their original projection screening. A DI theatre fine grade followed.”

He said the entire cast and crew of Jago Hua Savera comprised first-timers and Bengali star Tripti Mitra was the only actor of renown. “It is a great honour for Pakistan that Jago Hua Savera was chosen … it is one of these rare gems from the past; perhaps the only Pakistani film to win so many international awards,” Anjum wrote in an email.

The restored version has previously been screened at the New York Film Festival 2008 and the Three Continents Festival 2007.

Plight of the fisherfolk

The 50s were quite a time for cinema in the region. While the Satyajit Rays were wreaking havoc in Calcutta, the Guru Dutts in Bombay were belting out hits, one after another.

In Pakistan, like everything else, film production too was not in the best of conditions. One of the first Dhaka Studio productions, Jago Hua Savera was shot in three-and-a-half months at the fishing village of Shaitnol near the capital of present day Bangladesh. Filming equipment was ordered from the UK and US and taken to the location via river transport. Most of the crew members had flown in from abroad, including the Oscar-winning cinematographer Walter Lassally.

Jago Hua Savera tells the story of a fisherman who wants to one day own a boat of his own. In the backdrop of extreme poverty, he battles both the exploitation of the local moneylender and death.

In his essay Modernism and Film in South Asia, Rahul Sapra calls it the first realistic and experimental movie of Pakistan. “Jago Hua Savera was an exception, since the genre of melodrama, influenced by mainstream Indian cinema, continued to dominate Pakistani cinema,” he writes.

Amongst other accolades, the film won a gold medal at the inaugural Moscow International Film Festival in 1959. Linking it to the coming closer of Pakistan and the then USSR, Hafeez-ur-Rehman Khan in Pakistan’s Relations with the U.S.S.R calls the win “progress in cultural field”.

Faiz the screenwriter

How Faiz Ahmed Faiz got involved in the film merits a discussion on its own. In the recently published Love and Revolution: Faiz Ahmed Faiz – The Authorised Biography, Ali Madeeh Hashmi notes that after getting released from prison, Faiz had gained immense popularity. “In Pakistan, he was welcomed back from prison a hero. It was during this time that he met AJ Kardar, son of the famed film-maker AR Kardar, who was originally from Lahore and had been one of the pioneers of the film industry there.”

It didn’t take long for Kardar junior to convince the poet. “AJ Kardar persuaded Faiz to write a film script which Faiz based on one of his favourite novels, The Boatman of the Padma [a translation of Manik Bandhopadhyay’s classic, Padma Nadir Manjhi], about the lives of Bengali fishermen.”

In Faiz’s Letters to Alys, Salima Hashmi quotes an excerpt from her father’s letter to her mother during the time when he was writing the film. “In the last three days there has been no sun, the trees are dark with rain and the wind feels heavy with nostalgic regrets. My window brings memories of Simla and Kashmir and in the midst of work and discussions there are sudden stabs of homesickness and thoughts of you and the urge to drop everything and return. I could work so much better if you were here, but it can’t be helped so I’m trying to rush through it as speedily as I can.”

While the film owes greatly to its association with the larger-than-life figure that Faiz was, Bangladeshi film critic Alamgir Kabir notes, “Despite all its sincerity, Faiz failed to capture in the theme an authentic Bengaliness mainly because he never lived in this part of the country long enough to know its people and the land intimately enough.”

Drawing parallels between the film’s opening sequence and Luchino Visconti’s La Terra Trema, he wrote that the film offered a visual novelty for the foreigners but meant little for the East Pakistanis.

According to Pakistan Film Magazine, Jago Hua Savera was a commercial failure and was taken down from Karachi’s Jubliee Cinema (now Jubliee Centre) in just three days.

Tracing the reasons behind the film’s box office failure, Kabir says Jago Hua Savera could not be “understood by ordinary spectators as the language used in the film was a peculiar mixture of Bengali and Urdu easily understandable to neither community”. However, to him, the film remains the only example of efficient film-making in Pakistan.

In an interview with Ahmad Salim of the now-defunct Viewpoint, Faiz himself shed light on the film’s failure. “All right so you produce an ideological film like, for instance, Jago Hua Savera. Suppose it is ready for screening. But imagine the gatekeepers between the studio and cinema-screen do not share your ideology. They may not be concerned about its ideological point of view or its aesthetic aspect. As a result, it will not reach the audiences,” he said. Voicing another view that film puritans of today still hold, Faiz said, “It is a misconception that anything that has social perspective, or which has high aesthetic or technical standards will not be appreciated by the people.”

Inaugurated in 2004, Cannes Classics is a permanent fixture at the annual event that aims to celebrate film history. The festival will be held from May 11 to May 22 2016 and will be attended by the families of both Nauman and Faiz.