India- Bangladesh enclaves

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

2011: Protocol to the Land Boundary Agreement

Source:

Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India

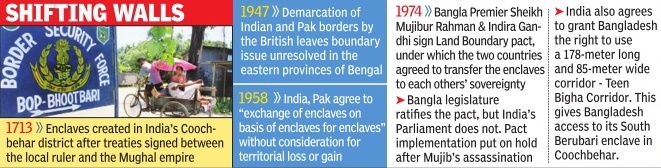

Attempts have been made to arrive at a comprehensive settlement of the land boundary between India and Bangladesh (the erstwhile East Pakistan) since 1947. The Nehru-Noon Agreement of 1958 and the Agreement Concerning the Demarcation of the Land Boundary between India and Bangladesh and Related Matters of 1974 (referred to as 1974 LBA ) sought to find a solution to the complex nature of the border demarcation involved. However, three outstanding issues pertaining to an un-demarcated land boundary of approximately 6.1 km, exchange of enclaves and adverse possessions remained unsettled. The Protocol (referred to as the 2011 Protocol) to the 1974 LBA , signed on 6th September 2011 during the visit of the Prime Minister to Bangladesh, paves the way for a settlement of the outstanding land boundary issues between the two countries. This historic agreement will contribute to a stable and peaceful boundary and create an environment conducive to enhanced bilateral cooperation. It will result in better management and coordination of the border and strengthen our ability to deal with smuggling, illegal activities and other trans-border crimes.

Executive summary

In building this agreement, the two sides (India and Bangladesh) have taken into account the situation on the ground and the wishes of the people residing in the areas involved. As such, the 2011 Protocol does not envisage the displacement of populations and ensures that all areas of economic activity relevant to the homestead have been preserved. The 2011 Protocol has been prepared with the full support and concurrence of the State Governments concerned (Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura and West Bengal). In planning the agreement, an elaborate process of consultation with people in the areas involved was carried out, including through the visit of an India–Bangladesh delegation to some of the enclaves and Adverse Possessions in May, 2007. The feedback received indicated that the people residing in the areas involved did not want to leave their land and would rather remain in the country where they had lived all their lives. The views of the concerned State Governments in favour of realigning the boundary to maintain status quo in respect of territories in adverse possession were also taken into account. Although this was contrary to the 1974 LBA , which stipulated the exchange of territories in adverse possession, both sides decided that to avoid large scale uprooting and displacement of populations against their wishes, it would be necessary to preserve the status quo and retain the adverse possessions as would be determined through joint surveys. The 2011 Protocol accordingly departs from the 1974 LBA in seeking to maintain the status quo of adverse possessions instead of exchange of territories in deference to the wishes of the people to remain in their land. 4 Land Boundary Agreement between India and Bangladesh Land Boundary Agreement between India and Bangladesh

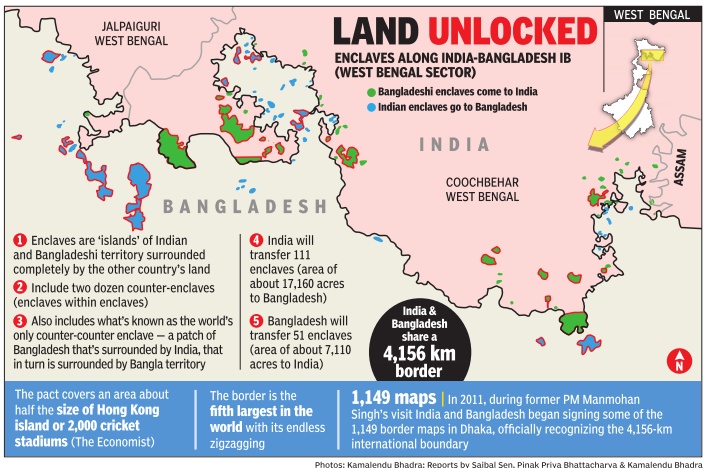

The 2011 Protocol will result in a fixed demarcated boundary in all the un-demarcated segments, exchange of 111 Indian enclaves in Bangladesh with 51 Bangladesh enclaves in India and a resolution of all adversely possessed areas. In the exchange of enclaves, India will transfer 111 enclaves with a total area of 17,160.63 acres to Bangladesh, while Bangladesh would transfer 51 enclaves with an area of 7,110.02 acres to India. While on paper, the exchange of enclaves between India and Bangladesh may seem like a loss of Indian land to Bangladesh, the actual scenario is quite different as the enclaves are located deep inside the territory of both countries and there has been no physical access to them from either country. In reality, the exchange of enclaves denotes only a notional exchange of land as the Protocol converts a de facto reality into a de jure situation. The inhabitants in the enclaves could not enjoy full legal rights as citizens of either India or Bangladesh and infrastructure facilities such as electricity, schools and health services were deficient. Further, due to lack of access to these areas by the law and order enforcing agencies and weak property rights, certain enclaves became hot beds of criminal activities. A number of Parliament Questions, representations from Members of Parliament, inhabitants of the enclaves, NGOs and political parties received over the years have urged Government to carry out an expeditious exchange of enclaves. In the implementation of the 2011 Protocol, the exchange of enclaves will have fulfilled a major humanitarian need to mitigate the hardships that the residents of the enclaves have had to endure for over six decades on account of the lack of basic amenities and facilities that would normally be expected from citizenship of a State. In respect of Adverse Possessions, India will receive 2777.038 acres of land and will transfer 2267.682 acres of land to Bangladesh through implementation of the 2011 Protocol. As in the case of enclaves, however, the reality is that the area to be transferred was already in the possession of Bangladesh and the handing over of this area to Bangladesh is merely a procedural acceptance of the de facto situation on the ground. Similarly, areas in adverse possession of India in Bangladesh will now be formally transferred to India with the implementation of the 2011 Protocol. More important, the 2011 Protocol will allow people living in the adversely possessed areas to remain in the land to which they have deep-rooted ties, sentimental and religious attachments. No constitutional amendment is envisaged for resolution of undemarcated sectors under the 2011 Protocol as this is within the competence of the Executive Wing of the Government. However, exchange of enclaves and the drawing of boundaries to maintain status quo of adverse possessions involving transfer and de jure control of territories requires a constitutional amendment. Article 368 of the Constitution states that “an amendment of this Constitution may be initiated only by the introduction of a Bill for the purpose in either House of Parliament, and when the Bill is passed in each House by a majority of that House and by a majority of not less than two-thirds of the members of that House present and voting, it shall 6 Land Boundary Agreement between India and Bangladesh Land Boundary Agreement between India and Bangladesh

Executive summary note on Land Boundary Agreement

India and Bangladesh signed a Protocol (referred to as the 2011 Protocol) to the Agreement concerning the demarcation of the Land Boundary between India and Bangladesh and related matters, during the visit of Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh to Dhaka, on September 6, 2011. The Protocol, along with the Agreement between India and Bangladesh concerning the demarcation of the Land Boundary between India and Bangladesh and related matters (referred to as 1974 LBA ), signed on May 16, 1974, has facilitated the resolution of the long pending land boundary issues between the two countries. The 2011 Protocol addresses the unresolved issues pertaining to the un-demarcated land boundary of approximately 6.1 km; exchange of enclaves; and adverse possessions. Maps indicating location of un-demarcated segments and Adverse Possessions (Annexure I) and Enclaves in India and Bangladesh (Annexure II) are attached.

NOTE on land boundary Agreement be presented to the President who shall give his assent to the Bill and thereupon the Constitution shall stand amended in accordance with the terms of the Bill.”A settled boundary is an essential prerequisite for effective cross-border cooperation. It reduces friction, helps neighbours consolidate mutually beneficial exchanges and promotes confidence in building better relations. The 2011 Protocol will ensure that the India-Bangladesh boundary is permanently settled with no more differences in interpretation, regardless of the government in power. This also helps on issues of security concern, including security cooperation and denial of sanctuary to elements inimical to India. Ratification of the 2011 Protocol would represent a historic step culminating in the resolution of the long pending land boundary issues between India and Bangladesh. The Agreement has been widely welcomed by the people of both countries, particularly in the areas involved. Its implementation will allow India and Bangladesh to focus on unlocking the full potential for mutually beneficial bilateral cooperation through enhanced security, trade, transit and development.

Background

(a) After the partition of India in 1947, the Radcliffe Line became the border between India and East Pakistan and following the liberation of Bangladesh in 1971, the same line became the border between India and Bangladesh. Although the demarcation of the border between India and the then Pakistan had started soon after the partition, progress was slower than expected, due in part to the difficulties in determining precisely where the border ran. Even though some of these boundary disputes were sought to be settled by the Nehru-Noon Agreement of 1958, subsequent hostilities between the two countries left the task unaccomplished. Even after the creation of Bangladesh, the boundary dispute between the two countries inherited the legacy of history and fractured politics.

(b) B oth countries were able to conclude the Land Boundary Agreement in 1974, soon after the independence of Bangladesh, to find a solution to the complex nature of border demarcation. The agreement has been implemented in its entirety, except for three outstanding issues pertaining to (i) undemarcated land boundary of approximately 6.1 km in three sectors viz. Daikhata-56 (West Bengal), Muhuri River-Belonia (Tripura) and Lathitila-Dumabari (Assam); (ii) exchange of enclaves; and (iii) adverse possessions. Although the Agreement was not ratified by India, its implementation, except for the issues mentioned above, represents significant progress, given the fact that both the countries share an approximately 4,096.7 km long land boundary. In respect of Dahagram and Angarporta enclaves of Bangladesh, Article 1(14) of the 1974 LBA provides for access to these enclaves by leasing in perpetuity an area of 178 metres X 85 metres near Tin Bigha. This was implemented through Letters of Exchange on October 7, 1982 between the then Foreign Minister of India and the then Foreign Minister of Bangladesh and on March 26, 1992 between the Foreign Secretary of India and the Additional Foreign Secretary of Bangladesh.

(c) D uring the visit of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina of Bangladesh to India in January 2010, India and Bangladesh expressed the desire to reach a final resolution to the long-standing problem and agreed to comprehensively address all outstanding boundary issues keeping in view the spirit of the 1974 Land Boundary Agreement. Subsequently, detailed negotiations, joint visits to the concerned areas and land surveys were undertaken, resulting in the Protocol concluded in September 2011.

(d) I n finalising the 2011 Protocol, the situation on the ground and wishes of the people residing in the areas involved were taken into account and the written consent of the concerned State Governments was obtained.

Documents

A summary of the documents relevant to the boundary demarcation issue between India and Bangladesh is given below:

(a) Agreement between the Government of the Republic of India and Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh concerning the demarcation of the land boundary between India and Bangladesh and related matters, May 16, 1974 (Annexure –III): The Agreement provided meticulous guidelines for an early and amicable delineation of the hitherto un-demarcated portions of the boundary in 13 sectors as well as for an expeditious resolution of related matters like the exchange of the enclaves and adverse possessions. The two Governments also agreed to give people citizenship rights of the State they were staying in, pending which status quo was to be maintained. Any dispute on account of interpretation or implementation of this Agreement was to be settled peacefully through mutual consultations.

(b) T erms of Lease in perpetuity of Tin Bigha - Area, October 7, 1982 and Implementing Tin Bigha Lease, 26 March, 1992

(Annexure –IV): I n terms of clause 14 of Article 1 of the Agreement between the Government of Republic of India and the Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh concerning the Demarcation of the Land Boundary between India and Bangladesh and Related Matters, signed in New Delhi on 16th of May 1974, India agreed to lease in perpetuity to Bangladesh, an area of 178 m x 85 m, or approximately 3.74 acres to connect these two enclaves with Panbari Mouza of mainland Bangladesh at a Token price of BD Taka 1 per annum which has since been waived off. The stipulated lease in perpetuity finally came into effect on June 26, 1992, with the Exchange of Letters. The lease connected the Bangladesh enclaves of Dahagram and Angarpota and mainland Bangladesh at alternate hours during the daylight period. Twenty-four hour access for Bangladesh nationals through Tin Bigha to the enclaves was acceded to during the Prime Minister’s visit to Bangladesh in September 2011, thus fulfilling a long standing request of Bangladesh. (c) The Protocol (2011 Protocol) to the Agreement between Government of India and Bangladesh concerning the Demarcation of Land Boundary between India and Bangladesh and Related Matters

(Annexure–V): The 2011 Protocol was signed on September 06, 2011, between the External Affairs Minister of India and the Foreign Minister of Bangladesh in the presence of the Prime Ministers of the two countries to address long pending land boundary issues between India and Bangladesh. The Protocol forms an integral part of the LBA 1974 and is subject to exchange of instruments of Ratification by the Governments of India and Bangladesh.

Difficulties in resolution of the land boundary dispute

(a) Berubari Dispute:

(i) In the standard model of geopolitics, international borders are clearly delineated, one-dimensional lines that absolutely separate sovereign states. In practice, however, borders are often contested and sometimes indistinct - and few are as fraught as the boundary separating India from Bangladesh. The Berubari dispute was one such, arising from an omission in the written text of the Radcliffe Award and erroneous depiction on the map annexed therewith. Radcliffe had divided the district of Jalpaiguri between India and Pakistan by awarding some thanas to one country and others to the other country. The boundary line was determined on the basis of the boundaries of the thanas. In describing this boundary, Radcliffe omitted to mention one thana, Thana Boda. Berubari Union No. 12 lies within Jalpaiguri Thana, which was awarded to India. However, the omission of the Thana Boda and the erroneous depiction on the map referred to above enabled Pakistan to claim that a part of Berubari belonged to it

(ii) The dispute was resolved by the Nehru-Noon Agreement of 1958 whereby, inter alia, half of Berubari Union No. 12 was to be given to Pakistan and the other half adjacent to India was to be retained by India. To implement this Agreement, the Constitution 9th Amendment Act and Acquired Territories (Merger) Act were adopted in 1960. This legislation was challenged in the courts by a series of writ petitions, which prevented the implementation of the Agreement. The Supreme Court decision on March 29, 1971, finally cleared the way for the implementation of the Agreement. This, however, could not be done because of the Pakistani Army crackdown in East Pakistan and the subsequent events which led to the emergence of Bangladesh as an independent country. Following the independence of Bangladesh, the LBA 1974 was signed to address the issues of border demarcations.

(b) Enclaves:

(i) The hasty partition of the subcontinent was flawed in several respects which left unresolved the fate of hundreds of ‘enclaves’ of both the countries. There are 111 Indian enclaves in Bangladesh (17,160.63 acres) and 51 Bangladesh enclaves in India (7,110.02 acres). The Indian enclaves in Bangladesh are located in four districts - Panchagarh, Lalmonirhat, Kurigram and Nilphamari. All of Bangladesh’s enclaves lie in West Bengal’s Kochbehar district.

(ii) The LBA 1974 agreement enabled Bangladesh to retain the Dahagram and Angarpota enclaves; India retained Berubari, which was contiguous. Article 1(12) of LBA 1974 states that enclaves should be exchanged. Further Article 3 stipulates that when areas are transferred, the people in these areas shall be given the right of staying on where they are, as nationals of the State to which the areas are transferred. While the LBA of 1974 has stated that the territory has to be exchanged, it had not specified any administrative procedures with respect to the people living in such territories till the exchange process was completed. India was keen to exchange enclaves in accordance with the LBA . There were, however, procedural issues that first needed to be addressed, including the determination of the number of people living in enclaves in both sides.

(c) Adverse Possessions:

(i) The Adverse Possessions have been a bone of contention between successive governments in India and Bangladesh and had impeded the final resolution of the boundary issue. Unlike enclaves, there was no jointly compiled and accepted list of adversely possessed territories or lands (except in South Berubari in West Bengal). The situation had been compounded by changes in the course of rivers and even encroachments, over the decades.

(ii) I t also became difficult to implement Article 2 of the 1974 LBA , which states that the two countries are expected to exchange the territories in Adverse Possessions in already demarcated areas after signing boundary strip maps by Plenipotentiaries. People living in the Adverse Possessions are technically in occupation and possession of land beyond the boundary pillars, but are administered by the laws of the country of which they are citizens and they enjoy all legal rights, including right to vote. They have deep-rooted ties to their land which goes back decades and are categorically unwilling to be uprooted. Many local communities had sentimental or religious attachments to the land in which they lived. It thus became extremely difficult to implement the terms of LBA 1974 as it meant having to uproot people from the land in which they had lived and developed sentimental and religious attachments to.

Justification

(a) Un-demarcated Segments:

Though the issue of the un-demarcated land boundary was addressed in the 1974 LBA , it could not be implemented due to differences of perception in the interpretation of the LBA and in view of the ground realities. The lack of clarity on the boundary between the two countries caused tensions and disrupted the lives of people living in these areas.

(b) Enclaves:

The inhabitants in the enclaves could not enjoy full legal rights as citizens of either country and infrastructure facilities such as electricity, schools and health services were deficient. Further, due to lack of access to these areas by the law and order enforcing agencies and weak property rights, certain enclaves became the hot bed of criminal activities. A number of Parliament questions and representations were received from Members of Parliament, inhabitants of the enclaves, NGO’s and political parties urging that the exchange of enclaves be expedited.

(c) Adverse Possessions:

(i) Despite the limited nature of dispute on the border, the non-settlement of Adverse Possessions has led to tension between the border guarding forces of the two countries. Muktapur, Pyrdiwah and Naljuri along the Meghalaya- Bangladesh border had witnessed firing incidents in the recent past. In Dumabari area (Assam) firing took place between the two security agencies as early as in 1962 and again in 1965. In Muhuri river area (Tripura), 10 incidents of firing were reported between BSF and BGB , the last reported in 1999. In Boroibari (Assam), in a firing incident in 2001, 16 BSF personnel were killed. Thus, the adverse possession areas have been flashpoints between India and Bangladesh exacerbating the tensions along the border and between the two neighbouring States. The issue got further complicated with the increasing population pressure in Bangladesh, use of Bangladesh soil for anti-India terrorist activities, and refuge for terrorists, militants and criminals. All of this necessitated the need for an early settlement of the outstanding land boundary issues between India and Bangladesh.

(ii) D uring the joint visit of an India-Bangladesh delegation in May, 2007 to the Adverse Possession in South Berubari, the people residing there expressed an unusually strong view that they would not accept an exchange of Adverse Possessions.

(iii) The Government of West Bengal in 2002 had suggested that the boundary be realigned with the line of actual possession, thus converting de facto control into de jure control. Similarly, the Government of Meghalaya was also reluctant to give up the territories in adverse possession and had requested that status quo be maintained along the adverse possessions.

Efforts towards a Comprehensive Package Solution

(a) I t was evident that a comprehensive resolution of the boundary issue was necessary at the earliest in the larger interest of the country’s security, furtherance of bilateral relations and regional stability and prosperity.

(b) I n resolving the issue of enclaves, a list of the enclaves, along with maps was jointly reconciled, signed and exchanged in April 1997.

(c) Keeping in mind the objective of seeking a viable solution, India and Bangladesh established the Joint Boundary Working Group (JBWG ) in 2001 to address the outstanding land boundary issues, namely, the border dispute comprising 6.1 km of an un-demarcated stretch, enclaves and adverse possessions. The JBWG met four times over the last ten years. The mandate given to the JBWG was to evolve a comprehensive package proposal to resolve all pending issues pertaining to the boundary dispute.

(d) During the 4th Meeting of the JBWG , India and Bangladesh agreed to take into account the situation on the ground and the wishes of the people residing in the areas involved in trying to find an expeditious solution to all outstanding issues. The two sides also decided to jointly survey the adverse possessions to come to a final determination about its status based on ground realities.

(e) A head count was conducted jointly by both sides from 14-17 July, 2011 according to which the total population in the enclaves was determined to be around 51,549 (37,334 in Indian enclaves within Bangladesh and 14,215 in Bangladesh enclaves within India).

(f) The concerned State Governments were closely associated with the process of determination of Adverse Possessions. Land records were scrutinized, the wishes of the people in possession of the lands were ascertained and land survey and index maps of the adversely held areas prepared by State Government surveyors. Similarly, the joint surveys of the boundary demarcation in the three un-demarcated segments were carried out by the State Survey Departments in their respective areas of the boundary with Bangladesh. There was close coordination between the Central and State authorities.

(g) In building this agreement, the two sides have taken into account the situation on the ground and the wishes of the people residing in the areas involved. As such, the Protocol does not envisage the dislocation of populations and ensures that all areas of economic activity relevant to the homestead are preserved

(h) A comprehensive package proposal was evolved to settle the outstanding boundary issues, in consultation with the Bangladesh side. This resulted in the signing of the 2011 Protocol.

Implications

(a) I n the exchange of enclaves, a de facto reality gets converted to a de jure situation. The areas in respect of enclaves that would be acquired by India and transferred to Bangladesh are placed at Annexure VI & Annexure VII, respectively.

111 Indian enclaves with a total area of 17,160.63 acres in Bangladesh are to be transferred to Bangladesh, while 51 Bangladesh enclaves with an area of 7,110.02 acres in India are to be transferred to India. While on paper, the exchange of enclaves between India and Bangladesh may seem like a loss of Indian land to Bangladesh, the actual scenario on the ground is quite different. These enclaves are located deep inside Bangladesh and there has hardly been any direct access to them from India since 1947. Similarly, Bangladesh has had minimal, if any, access to its enclaves located deep inside India. In effect, the exchange of enclaves denotes only a notional exchange of land.

(b) A joint headcount conducted from 14-17 July, 2011 determined the total population in the enclaves to be around 51,549 (37,334 in Indian enclaves within Bangladesh and 14,215 in Bangladesh enclaves within India). In respect of enclaves, the 1974 LBA states that the people in these areas shall be given the right of staying where they are as nationals of the State to which the areas are transferred. Feedback from a visit jointly undertaken by an India–Bangladesh delegation to some of the enclaves and adverse possessions in May 2007 revealed that the people residing in Indian enclaves in Bangladesh and Bangladesh enclaves in India did not want to leave their land and would rather be in the country where they had lived all their lives. Movement of people, if any, is therefore expected to be at a minimum level.

(c) I n respect of Adverse Possessions, it must be noted that in reality the transferred area has already been in possession of Bangladesh and the handing over of these areas to Bangladesh is merely a procedural formal acceptance of a de facto reality on the ground. The same applies to Indian Adverse Possessions within Bangladesh that would be transferred to the Indian Union in implementation of the 2011 Protocol. In the implementation of the Protocol, India will receive 2777.038 acres of land and transfer 2267.682 acres of land to Bangladesh. Adverse Possession areas that would be acquired by India and transferred to Bangladesh are placed at Annexure VIII & Annexure IX respectively.

(d) The 2011 Protocol provides for redrawing of boundaries to maintain the status quo of adverse possessions and has dealt with them on an ‘as is where is’ basis by converting de facto control into de jure recognition. People living in the Adverse Possessions are technically in occupation and possession of land beyond the boundary pillars, but are administered by the laws of the country of which they are citizens and where they enjoy all legal rights, including the right to vote. They have deep-rooted ties to their land which goes back decades and are categorically unwilling to be uprooted. Many local communities have sentimental or religious attachments to the land in which they live. Over time, it became extremely difficult to implement the terms of 1974 LBA as it meant uprooting people living in the adverse possessions from the land in which they had lived all their lives and to which they had developed sentimental and religious attachments. A joint visit by an India–Bangladesh delegation to some of the enclaves and adverse possessions undertaken in May 2007 revealed that the people residing in the areas involved did not want to leave their land and would rather be in the country where they had lived all their lives. Some of the concerned State Governments also had views on the issue. These and other inputs from the people involved made it evident to both sides that retention of status quo of adverse possessions seemed the only option. In any democracy, the will of the people must remain significant, and the 2011 Protocol has accorded highest priority to it - every effort has been made to preserve all areas of economic activity relevant to the homestead and to prevent dislocation of people living in the border areas. Both India and Bangladesh agreed to maintain the status quo in addressing the issue of adverse possessions instead of exchanging them as called for in the LBA , 1974.

(e) The demarcation of un-demarcated boundary in the three pending segments has followed ground realities, created a fixed boundary and resolved a problem that has eluded solution for decades. The boundary strip maps would have to be jointly prepared and signed by the Plenipotentiaries of the two countries to implement the understanding reached in the Protocol.

(f) Signing of the Strip Maps pertaining to Adverse Possessions would set the stage for exchange of land of the Adverse Possessions as well as exchange of land records and enclaves between the two sides.

(g) The implications pertaining to the concerned State Governments are given below with regard to adverse possessions and demarcation of boundary:

(i) W est Bengal: South Berubari, with a population of 15,000, is a sensitive area because of a temple regarded as one of 51 Shakti Peeths in the Indian subcontinent and an important pilgrimage spot for Hindus. The boundary in this sector has been drawn keeping in mind this sentiment and the agreement reached in the joint demarcation conducted in 1998 as a result of which South Berubari will be retained in India. In other areas too, such as Bousmari, old records, actual position on the ground and the people’s wishes were kept in mind while determining the extent of adverse possessions. With regard to demarcation of Daikhata 56, natural/geographical boundary in this region has been made the international boundary between the two countries, which is a normal practice in the demarcation of international boundary.

(ii) M eghalaya: The state government’s views on adverse possessions were accommodated through verification of actual position on the ground and wishes of the people. As a result of the joint survey in Pyrdiwah, the Adverse Possession has been recognized on the Indian side by Bangladesh. In Muktapur/Dibir Hawor area, the Protocol facilitates the visit of Indian nationals to Kali Mandir, drawing of water and exercise of fishing rights from the water body of Muktapur has been accepted. In other areas too, the homesteads and economic activities of Indian citizens has been protected.

(iii) T ripura: As agreed in the Protocol, the boundary shall be drawn along the course of Sonaraichhera River as per ground realities. With regard to demarcation of the Muhuri River/Belonia Sector, keeping in mind the ground realities as well as wishes of the people, the boundary in this sector has been finalised according to the local demand; the cremation ground area has been allotted to the Indian side and boundary has become a fixed boundary. Further, the Protocol has provisions of raising embankments by both the sides to stabilize the course of the river. To India’s advantage, fencing on zero line has also been agreed. Government of Tripura, while agreeing to the demarcation in this sector, has conveyed that compensation for the loss of private land may be provided on account of demarcation.

(iv) A ssam: The interests of tea and pan planters have been protected while finalizing the border between India and Bangladesh in this sector. With regard to demarcation of the Lathitilla and Dumabari sector, the line drawn by Radcliff and actual position on the ground has been followed.

Advantages

The major features of the 2011 Protocol regarding the India Bangladesh boundary are also its advantages. These are as follows:

➢ A s the Protocol is the outcome of bilateral negotiations, it is mutually acceptable and durable and paves the way for settlement of the long pending land boundary issues;

➢ I t takes into consideration the situation on the ground and the wishes of the people;

➢ I t takes into account the views of the concerned State Governments and has their written consent;

➢ The exchange of enclaves will mitigate major humanitarian problems as the residents in the enclaves and others on their behalf had often complained of the absence of basic amenities and facilities;

➢ The settlement of Adverse Possessions will lead to tranquillity and peace along the border;

➢ The Protocol provides for a comprehensive package solution involving “give and take” on both sides;

➢ I t represents a permanent solution to a decades old issue;

➢ The newly demarcated boundaries are a fixed boundary, thereby adding to certainty regarding the future;

➢ A settled boundary reduces friction, helps neighbours consolidate mutually beneficial exchanges and promotes confidence in building better relations.

➢ I t paves the way for closer engagement and mutually beneficial relations between India and Bangladesh and the region;

➢ This also helps on issues of strategic concern, including security cooperation and denial of sanctuary to elements inimical to India.

➢ W hile land will be exchanged, the Protocol does not envisage the displacement of populations;

➢ The Protocol ensures that the India-Bangladesh boundary is permanently settled and there should be no more differences in interpretation, regardless of the government in power.

Constitutional Amendment

No constitutional amendment is required for a resolution of the un-demarcated segments of the land boundary by an Agreement as this is within the competence of the Executive Wing of Government. However, the issue of exchange of enclaves and redrawing of boundaries to maintain status quo in areas of adverse possessions involves the transfer of territories from one State to another and therefore requires a constitutional amendment. Article 368 states that “an amendment of this Constitution may be initiated only by the introduction of a Bill for the purpose in either House of Parliament, and when the Bill is passed in each House by a majority of that House and by a majority of not less than two-thirds of the members of that House present and voting, it shall be presented to the President who shall give his assent to the Bill and thereupon the Constitution shall stand amended in accordance with the terms of the Bill”.

Conclusion

The effective management of our borders is the first essential step to creating a defined and peaceful boundary that will provide a stable and tranquil environment for cross-border cooperation with Bangladesh. The Protocol to the 1974 Land Boundary Agreement, signed on 6 September 2011 by the Foreign Ministers of India and Bangladesh in the presence of the Prime Ministers, paves the way for a settlement of the long pending land boundary issues between the two countries. This includes demarcation of the remaining undemarcated areas, territories under adverse possession and exchange of enclaves. In building this historic agreement, the overnment has received the full support and concurrence of the State Governments concerned. In implementing the agreement, people living in the border areas will not be dislocated.

The ratification of the Protocol to the 1974 Land Boundary Agreement would be a historic step culminating in the demarcation of the land boundary between India and Bangladesh, a task that has remained unresolved for decades, and not replicated elsewhere along our borders in recent times. Both sides have arrived at this Agreement in a spirit of friendship, mutual understanding and a desire to put these issues behind us. The Agreement has been welcomed by the people of both countries and will lead to easier management of the International Border by the border guarding forces. The implementation of the 2011 Protocol and 1974 LBA will lead to the India-Bangladesh boundary becoming stable and peaceful. It will ensure that people living along the border live in peace, amity and harmony. This will enable both countries to focus on other bilateral issues, including development of mutually beneficial cooperation and pave the way to realization of a common destiny through enhanced cooperation, growth and development of both nations.

Territory to be transferred to India (in acres)

West Bengal

Berubari and Singhpara-Khudipara (Panchagarh- Jalpaiguri): 1374.99

Pakuria (Khustia-Nadia) 576.36

Char Mahishkundi 393.33

Haripal/ LNpur (Patari) 53.37

Total 2398.05

Meghalaya

Pyrdiwah 193.516

Lyngkhat I 4.793

Lyngkhat II 0.758

Lyngkhat III 6.94

Dawki / Tamabil 1.557

Naljuri I 6.156

Naljuri III 26.858

Total 240.578

Tripura

Chandannagar (Moulvi Bazar-Uttar Tripura) 138.41

Total 138.41

Grand Total (APs) 2777.038

Territory to be transferred to Bangladesh (in acres)

West Bengal

Bousmari-Madhugari (Khustia-Nadia) 1358.25

Andharkota 338.79

Berubari (Panchagarh- Jalpaiguri) 260.55

Total 1957.59

Meghalaya

Lobachera-Nuncherra 41.702

Total 41.702

Assam

Thakurani Bari- Kalabari (Boroibari) (Kurigram-Dubri): 193.85

Pallathal (Moulvi Bazar -Karimganj) 74.54

Total 268.39

Grand Total (APs) 2267.682

Frequently asked questions

Q. Is Bangladesh in illegal occupation of Indian land?

A. There is no illegal occupation of Indian land by Bangladesh. Since independence, there have been pockets along the India- Bangladesh border that have traditionally been under the possession of people of one country in the territory of another country. These are known as Adverse Possessions. During the visit of the Prime Minister to Bangladesh in September 2011, a Protocol to the 1974 Land Boundary Agreement between India and Bangladesh was signed. The Protocol addresses outstanding land boundary issues, including the issue of adverse possessions, between the two countries.

Q. We understand that an Agreement on land boundary issues has been signed between India and Bangladesh during the visit of the Prime Minister to Bangladesh in September 2011. What are the main elements of this agreement?

A. I ndia and Bangladesh concluded a Land Boundary Agreement in 1974, soon after the independence of Bangladesh, to find a solution to the complex nature of border demarcation. The agreement was implemented in its entirety with the exception of three issues pertaining to (i) un-demarcated land boundary of approximately 6.1 km in three sectors, viz. Daikhata-56 (West Bengal), Muhuri River-Belonia (Tripura) and Lathitila- Dumabari (Assam); (ii) exchange of enclaves; and (iii) adverse possessions. Although the Agreement was not ratified by India, its implementation, except for the outstanding issues mentioned above, represented significant progress, given the fact that the two countries share an approximately 4,096.7 km long land boundary. The outstanding issues, however, contributed to tension and instability along the border and adversely impacted on the lives of people living in the areas involved. Those living in the enclaves could not enjoy full legal rights as citizens of either country and infrastructure facilities such as electricity, schools and health services were deficient. For those in adverse possessions, it meant an unsettled existence between two countries without the certainty of being able to cultivate their lands or lead normal lives. The need for a settlement of the outstanding land boundary issues between India and Bangladesh was, therefore, acutely felt and articulated by the people involved, the concerned state governments and others. Several attempts have been made to address the outstanding land boundary issues. It was, however, only with the signing of the Protocol to the 1974 LBA during the visit of the Prime Minister to Bangladesh on 6th September 2011 that a settlement to the outstanding land boundary issues between the two countries was achieved. The 2011 Protocol will result in a fixed demarcated boundary in all the un-demarcated segments, exchange of Indian enclaves in Bangladesh with Bangladesh enclaves in India and a resolution of all adversely possessed areas. This historic agreement will remove a major irritant in relations between the two neighbouring countries. It will contribute to a stable and peaceful boundary and create an environment conducive to enhanced bilateral cooperation. It will result in better management and coordination of the border and strengthen our ability to deal with smuggling, illegal activities and other trans-border crimes. In concluding the Protocol, the two sides (India and Bangladesh) have taken into account the situation on the ground, the wishes of the people residing in the areas involved and the views of the concerned State Governments. As such, the Protocol does not envisage the dislocation of populations and ensures that all areas of economic activity relevant to the homestead have been preserved. The Protocol has been prepared with the full support and concurrence of the concerned State Governments (Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura and West Bengal).

Q. Will signing of the Protocol to the 1974 Land Boundary Agreement lead to surrender of Indian land to Bangladesh?

A. The implementation of the Protocol will result in the exchange of 111 Indian enclaves in Bangladesh with 51 Bangladesh enclaves in India and preservation of the status quo on territories in adverse possession. In implementing the Protocol, 111 Indian enclaves with a total area of 17,160.63 acres in Bangladesh are to be transferred to Bangladesh, while 51 Bangladesh enclaves with an area of 7,110.02 acres in India are to be transferred to India. Moreover, with the adjustment of adverse possessions in the implementation of the Protocol, India will receive 2777.038 acres of land and transfer 2267.682 acres of land to Bangladesh. I n reality, however the exchange of enclaves and adverse possessions denotes only a notional exchange of land. The actual situation on the ground is that the enclaves are located deep inside the territory of both countries and there has been no physical access to them from either country. Thus the exchange of enclaves will legalise a situation which already exists de facto. Similarly, in the case of adverse possessions, the reality is that the area to be transferred was already in the possession of Bangladesh and the handing over of this area to Bangladesh and India respectively. The exchange of adverse possessions confirms that each country will legally possess the territories it is already holding.

Q. How will the three un-demarcated segments be demarcated?

A. W ith the signing of the Protocol, the un-demarcated land boundary in three sectors, viz. Daikhata-56 (West Bengal), Muhuri River-Belonia (Tripura) and Dumabari (Assam) have been demarcated. The demarcation of boundary in Daikhata-56 is based on status quo; in Belonia, demarcation has taken place along the Muhuri River charland while retaining the traditional cremation grounds on the Indian side of the boundary; and in Lathitila-Dumabari, demarcation has followed a mutually acceptable line. Joint survey of the boundary demarcation in the three un-demarcated segments was carried out by the Survey Departments of the respective State Governments. The demarcation has been carried out keeping in view the situation on the ground and the wishes of the people involved.

Q. How was the area of land involved in exchange of Enclaves determined?

A. A n agreed list of 111 Indian enclaves in Bangladesh and 51 Bangladesh enclaves in India was jointly prepared and signed at the level of Director General, Land Records & Surveys, Bangladesh and Director, Land Records and Survey, West Bengal (India) in April 1997. All Bangladesh enclaves in India are located in the state of West Bengal.

Q. How were the areas in Adverse Possession determined?

A. The concerned State Governments were closely associated with the process of determination of Adverse Possessions. Land records were scrutinized, the wishes of the people in possession of the lands were ascertained and land survey and index maps of the adversely held areas prepared by State Government surveyors. Joint surveys of the adverse possessions were carried out by the State Survey Departments in their respective areas of the boundary with Bangladesh. There was close coordination between the Central and State authorities.

Q. Has the Protocol deviated from the Land Boundary Agreement (LBA), 1974, and, if so, why?

A. A rticle 2 of the LBA 1974 states that the two countries are expected to exchange territories in Adverse Possession in already demarcated areas. The 2011 Protocol provides for redrawing of boundaries so that the adverse possessions do not have to be exchanged; it has dealt with them on an ‘as is where is’ basis by converting de facto control into de jure recognition. People living in territories in adverse possession are technically in occupation and possession of land beyond the boundary pillars, but they are administered by the laws of the country of which they are citizens and where they enjoy all legal rights, including the right to vote. They have deep-rooted ties to their land, which go back decades and are categorically unwilling to be uprooted. Many local communities have sentimental or religious attachments to the land in which they live. Over time, it became extremely difficult to implement the terms of 1974 LBA as it meant uprooting people living in the adverse possessions from the land in which they had lived all their lives and to which they had developed sentimental and religious attachments. Both India and Bangladesh, therefore, agreed to maintain the status quo in addressing the issue of adverse possessions instead of exchanging them as was earlier required for in the LBA , 1974.

Q. How will signing of Protocol help settle the boundary issue?

A. W ith the signing of the Protocol, the outstanding and long pending land boundary issues between India and Bangladesh stand settled. The un-demarcated boundary in all three segments, viz. Daikhata-56 (West Bengal), Muhuri River- Belonia (Tripura) and Dumabari (Assam) has been demarcated. The status of the 111 Indian enclaves in Bangladesh with a population of 37,334 and 51 Bangladesh enclaves in India with a population of 14,215 has been addressed. The issue of Adversely Possessed lands along the India-Bangladesh border in West Bengal, Tripura, Meghalaya and Assam has also been frequently asked questions frequently asked questions resolved. The implementation of the Protocol is expected to result in better management and coordination of the border and strengthening of our ability to deal with smuggling, illegal activities and other trans-border crimes.

Q. What will happen to people living in the areas involved once land is exchanged?

A. I n building this agreement, the two sides have taken into account the situation on the ground and the wishes of the people residing in the areas involved. In territories in adverse possession, status quo will be maintained so that there is no change for the people where they are located. The territories in adverse possession, will now become legally part of the State holding them. In respect of enclaves, the LBA 1974 states that the people in these area shall be given the right of staying where they are as nationals of the State to which the areas are transferred. Feedback from a visit jointly undertaken by an India–Bangladesh delegation to some of the enclaves and adverse possessions in May 2007 revealed that the people residing in Indian enclaves in Bangladesh and Bangladesh enclaves in India did not want to leave their land and would rather be in the country where they had lived all their lives. As such, the Protocol does not envisage the displacement of populations and ensures that all areas of economic activity relevant to the homestead are preserved.

Q. Does the Protocol take into account the wishes of the people?

A. The Protocol has been prepared in keeping with the wishes of the people living in the areas involved and in close consultation with the concerned State Governments. A joint visit by an India–Bangladesh delegation to some of the enclaves and Adverse Possessions in May 2007 revealed that the people residing in the areas involved did not want to leave their land and would rather be in the country where they had lived all their lives. These and other inputs from the people involved made it evident to both sides that retention of status quo of adverse possessions seemed the only option. With regard to enclaves, a number of Parliament questions and representations were received from Members of Parliament, inhabitants of the enclaves, NGO’s and political parties urging that the exchange of enclaves be expedited. In any democracy, the will of the people must remain significant, and the 2011 Protocol has accorded highest priority to it. In implementing the Protocol, every effort has been made to preserve all areas of economic activity relevant to the homestead and in ensuring that people living in the border areas are not dislocated.

Q. What does the Protocol envisage for enclaves?

A. The Protocol envisages that 111 Indian Enclaves in Bangladesh and 51 Bangladesh Enclaves in India, as per the jointly verified cadastral enclave maps and signed at the level of Director General Land Records & Surveys, Bangladesh and Director Land Records & Surveys, West Bengal (India) in April 1997, shall be exchanged.

Q. Why was the exchange of enclaves not undertaken earlier as stipulated in the LBA?

A. I ndia was keen to exchange enclaves in accordance with the LBA . There were, however, procedural issues that first needed to be addressed, including determination of the number of people living in enclaves in both sides.

Q. How have people living in the enclaves on both sides been identified? Do we have any indication of number of people living in the enclaves?

A. A headcount was conducted jointly by both countries from 14-17 July, 2011, and this revealed that the total population in the enclaves was 51,549 (37,334 in Indian enclaves within Bangladesh and 14,215 in Bangladesh enclaves within India).

Q. What will be the citizenship status of inhabitants of enclaves once they are exchanged?

A. A s per Article 3 of the LBA 1974, when the enclaves are transferred, people living in these areas shall be given the right of staying on where they are as nationals of the State to which the areas are transferred.

Q. Do we expect a large scale transfer of people between the enclaves on either side following implementation of the Protocol?

A. A joint headcount conducted from 14-17 July, 2011 determined the total population in the enclaves to be around 51,549 (37,334 in Indian enclaves within Bangladesh and 14,215 in Bangladesh enclaves within India). In respect of enclaves, the 1974 LBA states that the people in these areas shall be given the right of staying where they are as nationals of the State to which the areas are transferred. Feedback from a visit jointly undertaken by an India–Bangladesh delegation to some of the enclaves and adverse possessions in May 2007 revealed that the people residing in Indian enclaves in Bangladesh and Bangladesh enclaves in India did not want to leave their land and would rather be in the country where they had lived all their lives.

Q. How would people in the enclaves benefit from the exchange of enclaves?

A. I n the exchange of enclaves, India will transfer 111 enclaves with a total area of 17,160.63 acres to Bangladesh, while Bangladesh would transfer 51 enclaves with an area of 7,110.02 acres to India. The Protocol converts a de facto reality into a de jure situation. The inhabitants of the enclaves have not been able to enjoy full legal rights as citizens of either India or Bangladesh and proper facilities with regard to electricity, schools and health services since 1947. These facilities will accrue to them once the issue of enclaves is resolved with the ratification of the Protocol and its implementation. As such, implementation of the Protocol by way of the exchange of enclaves will have fulfilled a major humanitarian need to mitigate the hardships that the residents of the enclaves have had to endure for over six decades.

Q. What is the timeline for implementation of the Protocol?

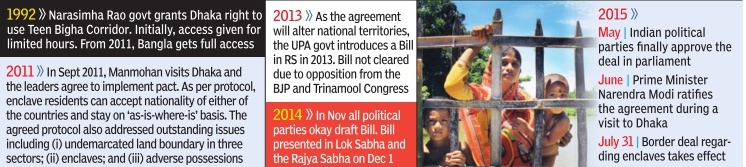

A. The Protocol was signed on September 06, 2011 to address the outstanding land boundary issues between India and Bangladesh. The Protocol shall be subject to ratification by the Government of the two countries and shall enter into force on the date of exchange of Instruments of Ratification. The Government of India proposes to introduce a Constitution Amendment Bill in Parliament as the issue of exchange of enclaves and redrawing of boundaries to maintain status quo in territories in adverse possessions involves the transfer of territories from one State to another necessitates a constitutional amendment. The adoption of the Constitution Amendment Bill is expected to lead to ratification of the Protocol and exchange of instruments of ratification followed immediately by implementation of the Protocol.

Q. What are the advantages of signing the 2011 Protocol?

A. The 2011 Protocol paves the way for settlement of the long pending land boundary issue by taking into consideration the situation on the ground and the wishes of the people involved. Its implementation, through the exchange of enclaves, will mitigate a major humanitarian issue as the residents of the enclaves have had to endure the absence of basic amenities and facilities for many decades in the absence of any such settlement. The settlement of Adverse Possessions will lead to tranquillity and peace along the border. A settled boundary would pave the way the way for a closer engagement and mutually beneficial relationship between India and Bangladesh.

Q. Why did H.E. Sheikh Hasina, Prime Minister of Bangladesh visit Tin Bigha on October 19, 2011?

A. D uring the visit of the Prime Minister to Bangladesh in September 2011, India announced 24-hour access for Bangladesh nationals through the Tin Bigha corridor with immediate effect, thereby fulfilling a longstanding request of Bangladesh. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina visited the Dahagram and Angarpota enclaves that are connected to the Bangladesh mainland by the Tin Bigha corridor. She personally witnessed access through the corridor and turned on the electricity connection to the enclaves facilitated by India.

In brief

The Times of India, Aug 01 2015

What's an enclave?

A patch of land encircled by another country's territory. India had 111 such enclaves within Bangladesh, which in turn has 51 of its enclaves within India. These enclaves dotted the Indo-Bangla land boundary in north Bengal and date back to 18th century when they were part of the Coochbehar and Rangpur princely states which merged with India and Pakistan respectively . Indian enclaves were spread over Panchagarh, Lalmonirhat, Kurigram and Nilphamari districts of Bangladesh. All Bangladeshi enclaves were situated in Coochbehar. With the merger of the princely states with India and Pakistan not changing the status of these enclaves, the people living in them did not enjoy full legal rights as citizens of either country . The areas lacked even basic infrastructure facilities such as electricity and schools, and health services were deficient. Some later became a hot bed of criminal activities.

How many people reside in these enclaves?

A joint headcount conducted in 2011 determined the population in the enclaves to be around 51,549 (37,334 in Indian enclaves and 14,215 in the ones in Bang ladesh). The total area covered by the 111 Indian en covered by the 111 Indian enclaves in Bangladesh is 17160.63 acres and the 51 Bangladesh enclaves in India is 7110.02 acres.

Will the new border alignment lead to a huge transfer of population?

So far not a single household living in the Indian enclave in Bangladesh has opted to move to Bangladesh. But 979 people living in the Bangladesh enclaves in India have opted to shift to Indian territory.

What are the problems in the Land Boundary Agreement?

People coming into India from Bangladeshi enclaves won't be given citizenship immediately . They must wait till November for formalities to be completed and are likely to face problems arising out of lack of state-backed residency proof and identity documents.

How the enclaves were formed

The Times of IndiaJun 01 2015

Jayanta Gupta & Pinak Priya Bhattacharya

These enclaves were part of the former Cooch Behar kingdom, which ceded pockets of territory to the Mughals and the British. When Cooch Behar acceded to India, parts of it which were in Bangladesh (then East Pakistan), naturally became part of India, except for the small technicality of them lying in another country . For decades, residents of the enclaves have lived in isolation in a sense: A Bangladeshi enclave, surrounded by India, is cut off from facilities and benefits from its own country . The same happens to Indians marooned in Bangladeshi territory . The constitutional amendment essentially allows the countries to swap land so that those living in the enclaves can get citizenship rights without having to move out of their traditional homes if they do not wish to. It will also settle the decades-old border disorder.

Low turnout for Indian citizenship in enclaves

The Times of India, Jul 25 2015

Debasish Konar

Jamaat role seen as just 979 from enclaves opt for India

Not many yes for Indian citizenship from the 37,000-odd people staying in Indian enclaves inside Bangladesh has raised the suspicion of a Jamaat-e-Islami hand in ensuring a very low turnout. Just 979 people, or about 2.6% of those living in the Indian enclaves, have opted for Indian citizenship. In stark contrast, all the 14,854 staying on Indian soil in Bangladeshi enclaves have sought Indian citizenship. A home department official said there were allegations that Jamaat had prevented Indian enclave-dwellers from freely exercising their option. The home ministry has been alerted on this, he added.

The numbers have even surprised officials as the Centre has assured a kitty of Rs 3,000 crore for rehabilitation of the people who shift from the Indian enclaves in Bangladesh. It was earlier estimated that around 13,000 people in the 111 enclaves would move to India.

Cooch Behar Trinamool Congress MP Renuka Sinha confirmed the development.She said several thousand Indians living in Indian enclaves in Bangladesh had not been able to express their option freely as they had been intimidated by Jamaat activists. “I have written to Union home minister Rajnath Singh and external affairs minister Sushma Swaraj. Those who wanted to opt for India were not allowed to do so. Jamaat activists put their thumb impressions on the option papers and stated Bangladesh as their choice,“ she alleged. Many enclave-dwellers working in different parts of India have complained to the district magistrate of Cooch Behar to make their option as they were intimidated, said Debabrata Chaki of the Indian Enclaves United Council. He said even people with land deeds were prohibited from exercising their option.

2015: Freedom from uncertain belongingness

The Times of India, Aug 01 2015

Saibal Sen & Pinak Priya Bhattacharya

Moshaldanga (West Bengal)

Bangladesh, India in historic enclave swap

At the stroke of midnight, 14,214 citizens of Bangladesh, who had been residing in 51 enclaves within India, became Indians. It's an independence that has come late, but arrived nonetheless. The tricolour was unfurled in these enclaves, at half-mast because India is mourning former President APJ Abdul Ka lam. At the same time, 111 Indian enclaves in Bangladesh merged with that country . Of the 37,000 living there, 979 have opted to move to India, allaying fears of a huge transfer of population when the historic Land Boundary Agreement became operative and both countries redrew their boundary maps along north Bengal.No one from the Bangladeshi enclaves in India has chosen to cross over. The total number of new Indian citizens will be 15,193. The swap will be completed by November 2015.

Dahagram-Angorpota

The Times of India, Aug 02 2015

Kept out of land deal, Bangla enclave is a chicken's neck

Saibal Sen & Pinak Priya Bhattacharya

Teen Bigha:

Fate sealed in 1974, no relief in sight

At the stroke of the midnight, India's 4096.7km boundary with Bangladesh was redrawn. A 68-yearold “aberration“ 51 Bangladeshi enclaves in India and 111 Indian enclaves in Bangladesh -was rectified. But with one exception.

A 4616.85 acre Bangladeshi land, inhabited by 3,165 families, firmly perched on India. Dahagram-Angorpota, a Bangladeshi enclave, remained out of the Indo-Bangladesh agreement signed by PM Narendra Modi and his Bangaldeshi counterpart Sheikh Hasina on June 6, 2015. Its history was written 23 years back, on June 26, 1992.

Dahagram-Angorpota is a chicken's neck. Hemmed by India on all sides, its lifeline is a five-minute walking stretch -the Teen Bigha Corridor -which India has leased out for “perpetuity“ to Bangladesh. The Teen Bigha Corridor (literally meaning three bighas of Indian land) connects Dahagram-Angorpota to Bangladesh's Lalmonirhat district and Patgram police station area.

The 1974 Land Boundary Agreement signed by Indira Gandhi and Sheikh Mujibur Rehman provided that India would retain half of Berubari Union No. 12 and in exchange Bangladesh would retain the Dahagram and Angorpota enclaves. The agreement further provided that India would lease in perpetuity to Bangladesh the Teen Bigha Corridor for the purpose of connecting Dahagram-Angorpota to Bangladesh.

This part of 1974 pact was implemented on June 26, 1992. This was done through exchange of letters on March 26, 1992. Therefore, this didn't fall under the ambit of the latest Indo-Bangladesh accord.

Utpal Ray, president of Kuchlibari Sangram Committee, said, “We had hoped that something will be done about the Dahagram-Angorpota. If enclaves are being considered an aberration, why retain one. DahagramAngorpota's 7.15 square miles boundary with India isn't fenced. The estimated 34,000 people living there will be best served if they become a part of India. Moreover, unrestricted access makes it a criminal haven.“

He added that representations in this regard were made to the senior NDA leadership, including external affairs minister Sushma Swaraj and home minister Rajnath Singh. “Even Bengal CM Mamata Banerjee had promised to consider the matter. Darjeeling MP S S Ahluwalia has already raised the matter in Parliament. We are not giving up hope,“ said Ray .

For an international treaty already signed, the demand for a rollback appears far-fetched.

Biswabar Ray (45), a state employee, said, “It has really left us trapped. If Bangladesh chooses to fence the Teen Bigha corridor, we will have no links with mainland India.“

Md Monirul Islam, a small-time trader, said, “Apart from connectivity , we will face other infrastructural woes. Take for example my village, Kalshigram. It has 390 voters, but for 68 years electricity hasn't yet reached us.“

Bikash Ray, employee in a private telecom company , said, “In their effort to woo Bangladesh, India can't deny the legitimate rights of its own citizens. The Teen Bigha corridor, earlier, had some movement restrictions. Now it's kept open day and night.It is choking us. Incidents of cattle smuggling are increasing. There's no security .Isn't this enough for the government to pay heed to our complaints?“

Pilot corridor for cargo movement soon

India and Bangladesh will soon identify a corridor as pilot for direct movement of cargo between the two countries. Both sides are scheduled to meet in September to identify the route and sources said this would be between a point in West Bengal and Bangladesh.Sources said the route will be suggested by Bengal and Bangladesh during this meeting.

This plan under Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Nepal (BBIN) agreement for movement of all types of vehicles aims at seamless transport of cargo and passenger vehicles in the region. “At present, the cargo coming from either side is transferred at the border to vehicles plying in that particular country,“ an official said. He added the success of this pilot will also mean that a vehicle carrying cargo from Bangladesh can reach Nepal directly using Indian roads.