Freedom of speech: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Constitutional provisions

Restrictions specified under Article 19(2)

The Times of India, Aug 10 2015

Dhananjay Mahapatra

Freedom of speech and expression guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution has long been regarded as the second most important after the right to life of a citizen. In recent times, it appears to be the most misused right in India, especially on the internet. Take, for example, the Yakub Memon hanging case.Views expressed on the issue were sharply divided on merits and veered to religious lines. It led to clash of ideologies, open spats, painting those who favoured execution as `bloodthirsty' and those who opposed it as `traitors'.

Freedom of speech on the internet is scaling new internet is scaling new heights every day with complete disregard for the restrictions specified under Article 19(2). Netizens are always in a rush. They post their views the moment they come across a statement.Mostly , it either gets a thumbs up or derisive criticism. The degree of controversy attached to an issue increases the severity of cuss words.

If one advocates stay of hanging of a terrorist, he gets slammed as a left-leaning activist fed on foreign funds. If one argues for the hanging, the `activists' slam him as a bloodthirsty rightwinger. By indulging in such slanderous accusations, ostensibly in exercise of right to freedom of speech, are the two groups not infringing upon the right to life of each other? For, right to life includes a life with dignity .

People may not agree with each other on a certain issue, but does it prevent them from being civil and secular while expressing their views? If a person has objection to such abuse on internet, does he have an effective legal remedy? Is it not cumbersome and a waste of time to go after those who use cuss words? And was this the intention of the Constitution-framers, and later the Supreme Court, to give such wide meaning and interpretation to freedom of expression?

In Shreya Singhal case, the Supreme Court recognized the problem that could arise if every person aggrieved by abusive criticism of his view on the internet was to make a request directly to the service provider to take down the offending comments.

It had read down Section 79(3)(b) of the Information and Technology Act contemplating action against service providers for abusive comments on websites hosted by them. It had said such action could be taken against the service provider only if it failed to comply with the court order directing it to take down the material which had been held to be abusive or offensive on the basis of a complaint. “This is for the reason that otherwise, it would be very difficult for intermediaries like Google, Facebook etc to act when millions of requests are made and the intermediary is then to judge as to which of such requests are legitimate and which are not,“ it had said.

But who will have the time and energy to pursue a case in a court of law by filing a complaint against persons who used abuses to criticize his view? The type and kinds of names under which comments are posted on websites these days would make it extremely difficult for a complainant to find out the actual name and address of the author who violated his dig nity and reputation. And when there is a systematic group attack against a view, it is better for the person to silently stomach the abuse.

The absence of protection against abuses, invectives and cuss words expressed freely to register dissenting view is the deterrent for many in society from using their real names to express views on the internet.

In a recent judgment on the criminality of a poet in using Mahatma Gandhi as a fictitious character and attributing abusive words to him to depict society , the Supreme Court said freedom of speech did not protect the poet from facing trial under Section 292 of Indian Penal Code for indulging in obscenity .

Justice Dipak Misra, writing the judgment in Devidas Ramachandra Tuljapurkar case, said a poet was “free to depart from the reality; fly away from grammar; walk in glory by not following the systematic metres; coin words at his own will; use archaic words to convey thoughts or attribute meanings; hide ideas beyond myths which can be absolutely unrealistic; totally pave a path where neither rhyme nor rhythm prevail; can put serious ideas in satires, notorious repartees; take aid of analogies, metaphors... and one can do nothing except writing a critical appreciation in his own manner and according to his understanding“.

Despite this poetic licence for freedom speech and expression, the SC was clear that “a person's human dignity must be respected, regardless of whether the person is a well-known figure or not“. But except for moving court against rogue elements on the internet, does a person aggrieved by a torrent of abuse have an immediate remedy? The time is ripe for legislators to think about it.

Judiciary on Right to Speech and Expression

SC: Remarks on premarital sex are Bona fide opinions

From the archives of The Times of India 2010

‘Remarks on premarital sex bona fide opinion’

There was redemption for south Indian actress Khushboo after five long years of battling 23 cases filed across Tamil Nadu against her remarks on prevalence of premarital sex in Indian cities. Putting an end to her harassment, the Supreme Court quashed all proceedings pending against her in trial courts, saying the complaints woefully lacked in evidence.

A bench comprising Chief Justice K G Balakrishnan and Justices Deepak Verma and B S Chauhan, said those who filed complaints against the 39-year-old actress were ‘‘extra-sensitive’’ about the remarks made by her in 2005 and had no proof that these had disturbed the peace or hurt people’s sentiments.

The Madras HC had on April 30 in 2014 refused to stay the proceedings in trial courts. Khushboo had introduced herself in the SC as a ‘‘famous south Indian actress, a mother of two young children’’ and said she was being harassed and victimized at the behest of people with vested interests who had filed 23 ‘‘false, frivolous and mala fide’’ complaints.

She had added that her fundamental right of freedom of speech and expression could not be curtailed by such persons.

The apex court agreed with Khushboo that her comments, to a news magazine, were in response to a survey conducted about pre-marital sex in big cities in India and that it was a bona fide opinion.

Judiciary has continually expanded its definition

The Times of India, Nov 05 2015

Arun Jaitley

Media's Right to Free Speech

India's judiciary has continually expanded the definition of this right since Independence The Constitution gave a pre-eminent position to the Right to Free Speech. Whereas, the other fundamental rights could be restricted thro ugh reasonable restrictions, the Right to Free Speech could only be restricted if the restriction had nexus with any of the circumstances mentioned in Article 19(2) of the Constitution. India's post-Constitution history is an evidence of the fact that many fundamental rights have seen their weakening in the past 65 years. The Right to Life and Liberty was literally extinguished during the Emergency . The Right to Trade has been adversely affected in the days of the regulated economy . The Right to Property was repealed during the Emergency .

However, the Fundamental Right of Free Speech and Expression has been consistently strengthened and never narrowed down. So a national policy of expanding and strengthening the right has continuously existed over a period of time.

In the initial years of the Constitution, the Supreme Court held that the excessive licence fee for starting a newspaper was constitutionally invalid.Subsequently , in the very first decade, it was held that the Wage Board imposing an unbearable burden on a media organisation, would offend Free Speech.

Can the business or commercial interest of a newspaper be segregated from the Right of Free Speech? Would the business of a newspaper fall within the domain of the Right to Free Trade or would it impact on the Right to Free Speech? In the Sakal newspaper's case, the Supreme Court was concerned with the policy imposed in 1960, wherein the government decided to regulate the selling price of a newspaper. The sale price would depend on the number of pages. The government contended that it was only restricting the Right to Trade by a reasonable restriction in consumer interest. The Supreme Court held that, if a newspaper was compelled to raise its price on account of the thickness of the newspaper it would have two consequences, either the thickness, ie, the content would be reduced or alternatively, a newspaper would be compelled to raise its price, and, there was empirical evidence to suggest that an increase in price leads to loss in circulation.Thereby, the Right to Circulate is also a part of Free Speech.

Similarly , when the government restricted the size of a newspaper on the ground that newsprint was scarce on account of paucity of foreign exchange and excessive imports would lead to an outgo of foreign exchange, the Supreme Court held that curtailing the number of advertisements in a newspaper would impact Free Speech, since advertisements themselves supplement the cost of content.

In a landmark judgment in the newsprint customs duty case, the court was confronted with the question whether imposition of customs duty on newsprint can be challenged on the ground of it being `Tax of knowledge'. The court held that the business of a newspaper could never be segregated from its content.

In the Constituent Assembly , Ramnath Goenka had raised the issue that future governments would not resort to crude methods like censorship but would pinch the pockets of the newspapers. Agreeing with this view, the court held that newspapers shape the human mind, excessive tax on a newspaper itself could impact Free Speech if the purpose of the tax was not merely to raise revenue but to excessively burden the economy of the newspaper.

In the case of any trade, business or profession, taxation would be struck down only if it is confiscatory in nature, that is, if it makes the business impossible. But in the case of a media organisation, if it adversely impacts the Right to Free Speech, that is, makes it excessively costly and prohibitive, then the tax itself can be challenged as an invasion of Free Speech.

Most other democracies have not accepted the American precedent, but we in India went ahead and accepted this particular right. I think in its entire evolution, the customs duty case in its exposition of law and expanding the right became a landmark, in that the distinction between the business of Free Speech and the right of actual content of Free Speech itself, was obliterated.

Carrying this logic further, the Supreme Court, in the Tata Yellow Pages case, included commercial Free Speech, ie, advertising, to be a part of Free Speech. This proposition is still doubtful, since it could enable `paid' news to take the benefit of commercial speech being a part of Free Speech.

Paid news is a reality , and therefore if you follow the dicta of the American judgments which Tata Press has followed in India, will Free Speech also provide a right which extends to paid news? Obviously it does not sound logical, and therefore this issue has not come up before the courts. However, if there was to be a penal provision against paid news, it would have to be tested on the touchstone of whether it violates Free Speech or not.

Hate speech

The Times of India, Oct 05 2015

In India, there is no law that defines hate speech

What is hate speech?

Hate speech is a term used for a wide range of negative discourse linked with the speaker's hatred or prejudice against a certain section of society . It could be degrading, intimidating and aimed to incite violence against a particular religion, race, gender, ethnicity , nationality , sexual orientation, disability, political views, social class and so on. History has many examples when hate speeches were used to trigger eth nic violence resulting in genocide, as happened with the Jews in Nazi Germany and the Tutsi community in Rwanda.Regulation on hate speech is a post-Second World War phenomenon.

Isn't restriction on free speech unconstitutional?

Issues related to hate speech are often countered with the argument about freedom of speech. Given India's diversity , the drafters of the Constitution felt it was important to ensure a culture of tolerance by putting some restraints on freedom of speech. Sub-clause (a) of clause 1 of Article 19 of the Constitution states that all citizens have the right to freedom of speech and expression. However, it also states that the state can put reasonable restrictions on the exercise of this right in the interest of sovereignty and integrity of the country , security of state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency and morality and in rela tion to contempt of court.

What are the laws against hate speech in India?

Various sections of IPC deal with hate speech. For instance, according to Sections 153A and 153B, any act that promotes enmity between groups on grounds of religion and race and is prejudicial to national integration is punishable. Section 295A of IPC states that speech, writings or signs made with deliberate intention to insult a religion or religious beliefs is punishable and could lead to up to three years of jail. Simi larly the Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955, which was en acted to abolish untouchabili ty, has provisions penalising hate speech against Dalits. De spite the existence of all these laws, the Supreme Court in March 2014 asked the law com mission to suggest how hate speech should be defined and dealt with since the term is not defined in any existing law.

Can a community, class or caste be targeted in a political speech?

Section 125 of the Representation of the People Act restrains political parties and candidates from creating enmity or hatred between different classes of citizens of India. Also Section 123(3) of the Act states that no party or candidate shall appeal for votes on the ground of religion, race, caste, community , language and so on.

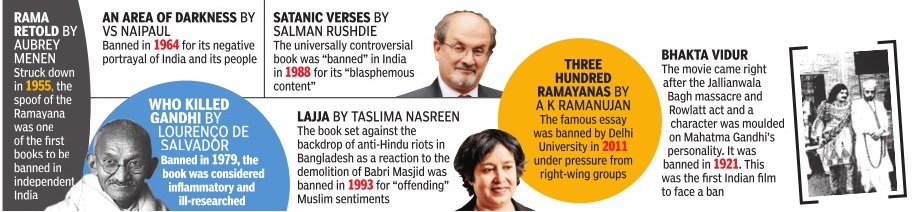

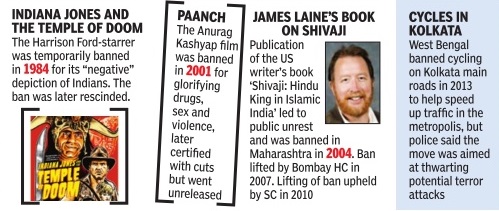

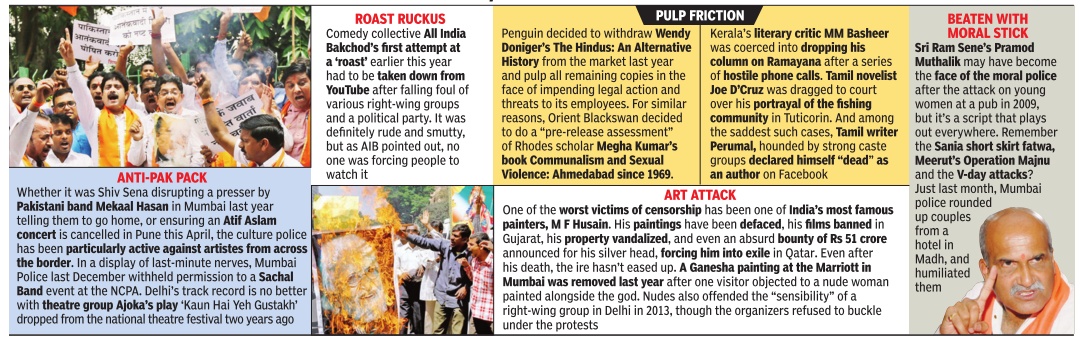

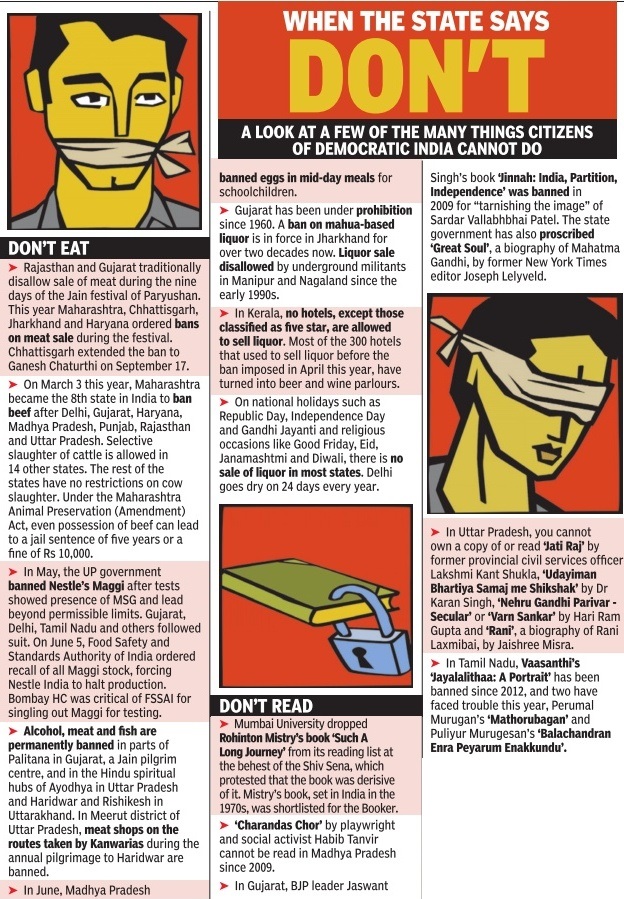

Banning works of art

The Indian SC: Mixed record on bans

The Times of India, Sep 15 2015

Manoj Mitta

To bar or not to bar: SC has mixed record

For all its claims to being a sentinel of liberty , the Supreme Court has a mixed record in responding to various bans challenged before it over the years. Though the positions it took on bans on goat slaughter, cow slaughter, homosexuality and religious conversions are far from liberal, the best precedent that can perhaps be applied to the current dispute arising from Maharashtra's meat ban is from the same state. It was a 2013 SC judgment lifting the ban on dance bars in Maharashtra. But then, the very next year the state assembly passed a fresh law re-imposing the ban, avoiding this time the legal infirmity of discriminating between ordinary dance bars and those run in luxury hotels. The blanket ban on dance bars is liable to be struck down on the ground of violating the fundamental right of owners and employees “to practice any profession or to carry on any occupation, trade or business“, an issue that was very much reflected in the SC verdict.

This fundamental right enshrined in Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution is, not surprisingly , central to the petition filed by the Bombay Mutton Dealers Association challenging the Maharashtra government's decision to prohibit not just the slaughter of goats but also the sale of mutton for some days in deference to the Jain festival of fasting, Paryushan.

Further, the meat ban decision, like the one related to the dance bars, involves a glaring issue of discrimination too. For, the ban does not extend to the sale of fish.And, as has been widely reported, all that the government counsel could say in the Bombay HC in defence of the discrimination was that there was no slaughter in the case of fish as they would automatically die once they were taken out of water. The wishy-washy explanation has exposed the legal vulnerability of the meat ban, which has political and communal overtones.

All the same, the partisans of the Mumbai meat ban may fancy their chances because of a 2008 SC verdict upholding a similar restriction in Ahmedabad. Even there, the meat ban was in deference to the same Jain festival and the challenge came from the local lobby of butchers. To validate the meat ban in Ahmedabad, the SC had to overrule the Gujarat HC.

Such illiberal rulings from the SC are found on other kinds of bans too. Take its 2005 judgment reversing its own position on the vexed issue of cow slaughter. Way back in 1958, the SC had held that the ban on cow slaughter envisaged by Article 48 did not extend to the cattle that was “not capable of milch or draught“. As a result of the 1958 verdict, various states had allowed the slaughter of cattle that could be classified as “useless“. But all this changed in 2005 when the same SC ruled that the Article 48 ban extended to all the cattle, irrespective of their age and the strain they put on the availability of fodder.

Another blow struck by the SC to liberty was in 2013 when it reinstated the ban on homosexuality . This was a reversal of the historic judgment passed by the Delhi high court in 2009 reading down Section 377 IPC to exempt consensual sex between adults of the same gender from any criminal liability. The Supreme Court verdict of 2013 put the clock back as it re-criminalized all homosexual acts, in effect privileging public morality over constitutional morality .

Similarly , the SC took a retrograde view on laws banning religious conversions.In keeping with the right to propagate religion guaranteed by Article 25, the laws passed by some of the states forbade only those conversions that were based on coercion or fraud. Contrary to the debates held in the Constituent Assembly , the SC held in 1977 that the right to propagate religion did not confer a right on anybody to convert others. While allowing efforts to spread the tenets of a religion, the apex court ruled that anybody engaged in conversion was automatically liable to be punished, even if it was not based on any extraneous considerations.

Insulting comments: SC upholds ban on book against Islam

From the archives of The Times of India 2010

The SC said it was more concerned with peace in society than a person’s fundamental right to freedom of speech and upheld a Maharashtra government ban on a book titled “A Concept of Political World Invasion by Muslims”.

Petitioner R V Bhasin had challenged Maharashtra’s decision four years after the publication of the book to ban it on the ground that it perpetrated hatred. The Bombay HC had said that government committed no wrong by banning the book. “The way this sensitive topic is handled by the author, it is likely to arouse the emotions and sensibilities of even strong minded people... criticism of Islam is permissible like criticism of any religion and the book cannot be banned on that ground...But the author has gone on to pass insulting comments.”

SC: No poetic licence to make Bapu swear

The Times of India, May 15 2015

Dhananjay Mahapatra

The Supreme Court ruled against poetic licence stretching the right to freedom of expression to cast revered figures like Mahatma Gandhi as a character in a fictional work and attributing obscene words to him.

A bench of Justices Dipak Misra and P C Pant upheld the prosecution launched against Devidas Ramachandra Tuljapurkar, editor of magazine `Bulletin' meant for private circulation among members of the All India Bank Association Union, for the poem `Gandhi Mala Bhetala' (I met Gandhi). The poem, written by Vasant Dattatreya Gurjar, was published in the July-August 1994 issue of the magazine. However, it discharged the printer and publisher as they had tendered apologies.

The judgment, authored by Justice Misra, dealt exhaustively with the issue of obscenity , referred to works of famous authors and poets across the world, extracted passages from 40-odd books on Gandhi written by Indians and foreigners and tested poetic licence on the touchstone of `contemporary community standards'.

The question before the court was “whether in a write-up or a poem, keeping in view the concept and conception of poetic licence and the liberty of perception and expression, using the name of a historically respected personality by way of allusion or symbol is permissible“? Using his educational background in literature, Justice Misra dug deep into the works of famous authors to convey what poetic licence was intended to serve and whether using historically revered figures as characters in a poem and attributing obscene words to them served that purpose. Tuljapurkar had claimed that he used the obscene words, as if spoken by Gandhi, to convey the angst in society. He faces prosecution under Section 292 of IPC, which is punishable by upto five years in jail.

The bench accepted sub missions of amicus curiae Fali S Nariman, who said, “Words that had been used in various stanzas of the poem, if spoken in the voice of an ordinary man or by any other person, it may not come under the ambit and sweep of Section 292, but the moment there is established identity pertaining to Mahatma Gandhi, the character of the words change and they assume the position of obscenity .“

The SC said, “Freedom of speech and expression has to be given a broad canvas, but it has to have inherent limitations which are permissible within the constitutional parameters.“ An author's fallacy in imagination could not be attributed to historically revered figures to diminish their value in the minds of people, the bench said. If an author used obscene words and attributed it to such personalities, then he travelled into the field of perversity , it added.

Restricting Internet, cellphones

Gujarat HC upholds mobile internet curfew during Patel stir

The Times of India, Sep 19 2015

Says the ban was `just and proper'

The Gujarat high court has upheld the state government's decision to impose a week-long mobile internet ban in August 2015 when riots broke out on August 25 following the arrest of Hardik Patel, the torchbearer of the ongoing Patidar reservation stir. Terming the ban “just and proper“, the court turned down a PIL filed by law student Gaurav Vyas, who had challenged the blocking of mobile internet services on the ground that it violated fundamental rights. Vyas had also questioned the city police commissioner's invocation of CrPC's Section 144 (power to issue orders in urgent cases of nuisance or apprehended danger) to restrict mobile internet services.

The petitioner contended that the government should have blocked certain websites or services by applying Information Technology Act's Section 69A (blocking content in case security of state is threatened). “Applying Section 144 of CrPC to block internet is arbitrary and beyond the scope of the provisions of the law,“ he argued in his plea.

In response, the government submitted that there was sufficient and valid ground to exercise CrPC's Section 144 to block mobile internet services, as “it would have been difficult to restore peace otherwise“. The state government also submitted that the exercise of power was not extreme since internet was still accessible on broadband and Wi-Fi services.

After hearing the case, the court said Section 144 of the CrPC was exercised for preventive action. In a given case, Section 69A of the IT Act might be exercised for blocking certain websites, whereas directions could be issued under CrPC provisions to service providers to block internet facilities. The petitioner's advocate said they planned to move the SC against the HC order.