Freedom of speech: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

What is free speech?

Definition, debate

`I Am Right, You Are Wrong' Infection Toxic

To define free speech is an arduous task. It is much easier to exerci se the right to free speech and expression guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) to all those who abide by our Constitution.

Article 19 itself constricts free speech in exceptional circumstances. But neither the Constitution nor the Supreme Court, in its numerous judgments protecting Article 19(1) (a), have given an exhaustive analysis of what free speech could be.

A middle-aged journalist was recounting his experience with free speech.He grew up in a large family where only the father had the right to free speech. Any counter argument was regarded as committing the sacrilege of talking back to father. Was his right to free speech violated?

When he had his own family, he was constantly sniped at by his children, exercising their free speech to point out how his spoken English had an awful regional accent which many a time made him prefer silence.Since evolution, family and social norms have put fetters on free speech.

The personal experience of the journalist is inconsequential when one looks at societal norms that constrict free speech. For centuries, Dalits did not have the freedom of speech to criticise upper castes. They still don't.When they decide to resort to free speech, it often invites blood-soaked humiliation.

Free speech on a cricket field has in the past invited ugly spats. Free speech against judges invite contempt charges. In contrast, expletives are not part of free speech, yet it is freely used on Delhi streets. Free speech comes from free thinking, which takes place in a free environment.Has India provided a free environment that encourages free thinking? Are social norms evolved through this collective thinking conducive for free speech?

A case in point is the free articulation of one's sexual identity . The third gender cowered under the threat of prosecution and persecution for centuries. Thanks to the cases in the Delhi high court and the Supreme Court, big cities have somewhat come to terms with people going public with their sexual orientation. Still, the social stigma is so unnerving that only a few rich and famous have dared to articulate their sexual preferences.

At present, free speech has sparked a fiery debate in Delhi that refuses to be doused. A 20-year-old exercised her right to speak her mind.A legendary cricketer, who enthralled spectators with fearless batting, responded.Both these were in exercise of free speech.

But a famous lyricist muddied the free speech debate by calling the cricketer a “hardly literate player“, though he later took back his words. Is free speech the fiefdom of the so-called educated? These so-called educated use their free speech as sermons and get angry when they encounter a witty counter through free speech exercised by not so educated, yet well informed, persons. The “I am right, you are wrong“ infection has taken a virulent form during this free speech fever. Tolerance for other's right to free speech is dwindling fast.

While dealing with an incident relating to the eviction of yoga guru Baba Ramdev from Ramlila grounds in Delhi, the Supreme Court on February 23, 2012, had given one of its finest discourses on the virtues of free speech. It had said, “Freedom of speech is the bulwark of the democratic process. Freedom of speech and expression is regarded as the first condition of liberty . It occupies preferential position in the hierarchy of liberties, giving succour and protection to all other liberties. It has been said that it is the mother of all liberties. Freedom of speech plays a crucial role in formation of public opinion on social, political and economic matters.“

It will be easier to articulate the contours of free speech by referring to reasonable restrictions in Article 19 (2) and the defamation laws.But it would almost be impossible to sum up what should be the contents of free speech. Free speech, the right to exercise it by oneself and others, would be more enjoyable and informative if those participating in a debate kept in mind two words -`tolerance and fraternity’.

One must not weaken fraternity among Indians while exercising free speech, and be tolerant to others' views, even if it is a caustic counter to one's own earlier words said in exercise of free speech.

R. Guha: Eight major threats to freedom of expression

Eight reasons why India cannot speak freely, TNN | Sep 11, 2016

By Ramchandra Guha

In a new book, Ramachandra Guha finds out what's eating away at the moral and institutional foundations of Indian democracy

Some years ago, I characterized our country as a '50-50 democracy'. India is largely democratic in some respects such as free and fair elections… but only partly democratic in other respects. One area in which the democratic deficit is substantial relates to freedom of expression.

Let me analyse what I regard as the eight major threats to freedom of expression in contemporary India. The first threat is the retention of archaic colonial laws. There are several sections in the Indian Penal Code (IPC) that are widely used (and abused) to ban works of art, films, and books... These sections — of which the most dangerous is Section 124A, the so-called sedition clause — give the courts and the state itself an extraordinarily wide latitude in placing limits to the freedom of expression.

The second threat is constituted by imperfections in our judicial system. Our lower courts in particular are too quick and too eager to entertain petitions seeking bans on individual films, books or works of art... The life of a book or a work of art or a film has become increasingly captive to the ease with which a community, any community at all, can complain that its sentiments, any sentiments, are hurt or offended by it...

A third threat is the rise and rise and further rise of identity politics. In India today, we imagine our heroes to be absolutely perfect. I wonder if this was always so. Yudhishthira and Rama were capable of deceit and deviant behaviour — and our ancestors were not surprised or angered to know this. But now Bengalis shall be enraged at even the mildest criticism of Subhas Chandra Bose, Tamils at the mildest criticism of Periyar, Maharashtrians at the mildest criticism of Shiva ji, Dalits at the mildest criticism of Ambedkar, Hindutvawadis at the mildest criticism of Savarkar, and so on.

Indians are increasingly touchy, thin-skinned, intolerant, and, I must add, humourless. The rise of humourlessness is the other side of the rise of identity politics. And without humour, there cannot be great literature.

The fourth threat to freedom of expression in India is the behaviour of the police force. Even when courts take the side of writers and artists, the police generally side with the goondas who harass them.

The fifth threat is the pusillanimity or, more often, the mendacity of politicians. Indeed, no major or minor Indian politician, as well as no major or minor Indian political party, has ever supported writers, artists or film-makers against thugs and bigots. Rajiv Gandhi's Congress government banned Salman Rushdie's novel The Satanic Verses even before Ayatollah Khomeini issued his fatwa against it. In West Bengal, the (well-educated and professedly literature-loving) communist chief ministers Jyoti Basu and Buddhadeb Bhattacharya had Taslima Nasrin's novels banned, and even had the author externed from the state. The record of the BJP is no better. The vandalism of the Husain-Doshi Gufa happened when Narendra Modi was chief minister of Gujarat.

While he was in that post, Hindutva activists effectively destroyed the country's best art department, at the Maharaja Sayajirao University in Baroda. Moving on to the leaders of regional parties, neither Jayalalithaa nor M. Karunanidhi did anything to protect the novelist Perumal Murugan when he was coerced by a group of caste vigilantes in Tamil Nadu to stop writing altogether. In acting (or nor acting) as they do, these politicians are motivated largely by electoral considerations. They do not wish to offend, or to be seen to be offending, a particular caste, sect or religious group, lest they vote against them in the next election.

A sixth threat to freedom of expression is constituted by the dependence of the media on government advertisements. This is especially acute in the regional and sub-regional press...The state and political parties can, and do, coerce, suppress or put barriers in the way of independent reporters and reportage. So can the private sector, using material rather than punitive force. Thus, a seventh threat to freedom of expression is constituted by the dependence of the media on commercial advertisements. This is especially pertinent in the case of English-language newspapers and television channels that cater to the affluent middle class. Companies that make products that have damaging side effects are rarely criticized for fear that they will stop providing ads...

I come now to my eighth and final threat to freedom of expression. This is constituted by careerist or ideologically driven writers. To be sure, most writers and artists have strong opinions on politics and society. That is why we write, that is why we paint, that is why we make films, that is why we write plays. But no creative person should be so foolish or mistaken as to mortgage his or her independence, his or her conscience, to a political party.

Edited excerpts from Democrats and Dissenters, Allen Lane (Penguin Random House)

J&K called ‘occupied’

April 28, 2022: The Times of India

Srinagar: The Jammu and Kashmir High Court ruled on Wednesday that calling Kashmir “occupied Kashmir” and its residents as “slaves” does not enjoy protection under the Constitution’s Article 19 (A) on right to freedom of speech and expression.

A bench of Justice Sanjay Dhar, hearing a petition filed by advocate Muzamil Butt seeking quashing of an FIR against him under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, remarked: “It is one thing to criticize the government for its negligence and express outrage on the violation of human rights of the people, but it is quite another to advocate that the people of a particular part of the country are slaves of the government of India or that they are under the occupation of armed forces of the country,” online portal Bar and Bench reported.

Police had registered an FIR against Butt for his Facebook post in which he criticized the killing of seven civilians in an explosion at the encounter site in Larnoo village in October 2018.

Muzamil Butt had also expressed outrage on social media platforms at other incidents of violence, which, he argued, was within his right to free speech. “By making these comments, Butt was supporting the claim that Jammu and Kashmir is not a part of India,” the court said. IANS

Parties fail to honour tolerance

The Times of India Jan 04 2016

Dhananjay Mahapatra

Tolerance had been the most used word in poli tics and social media for a good part of last year. In a fashionable and contemporary evolution of the term `tolerance', litterateurs returned awards given to them. Bollywood icons expressed their fear against growing intolerance. Political parties stalled Parliament to register their protest against intolerance.

Today social networking sites -Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp -are the key reflectors of public opinion.The young and not so young possess smartphones that update them about every single event. And in a matter of seconds, they register their reaction and opinions. Their opinion matters.

Public opinion mattered a lot with rulers from time immemorial. Even the Ramayana describes how Lord Rama was forced to abandon his wife Sita after rescuing her from the clutches of Ravana merely on the basis of public perception despite knowing that there was no truth behind the public opinion.

In the Jataka stories, we had read how a Brahmin was duped of a goat by three thieves. When the Brahmin was on his way back home with the goat, the three separately went to him and each of them insisted that it did not behove a Brahmin to carry a dog.The Brahmin shooed away the first thief with abuses. When the second one reiterated the same thing, a doubt crept into the Brahmin's mind. And a little later, when the third one too insisted with vehemence that it was a dog, the Brahmin believed it and ran away abandoning the goat. The gang of three had a nice feast, says the Jatakastory .

That is the power of public opinion and politicians have understood it. In the recent past, political parties had hired IT professionals to create trends in social network ng sites with catchy presentation of incidents and views of their leaders to garner maximum hits. AamAadmi Party has left everyone behind on this count.

The power of public opin on stems from the fact that our Constitution provides citizens with right to freedom of speech, a guarantee that had been broadened by the Supreme Court through its numerous judgments over the years. During the time when here was not much debate on tolerance and social networking sites were absent, he SC in S Rangarajan vs P Jagjivan Ram [1989 (2) SCC 574] had given a far-sighted ruling which even today could be referred to aptly in view of the tolerance debate.

It had said: `The different views are allowed to be expressed by proponents and opponents not because they are correct, or valid but because there is freedom in this country for expressing even differing views on any issue...Freedom of expression which is legitimate and constitutionally protected, cannot be held to ransom by an intolerant group of people.“

“The fundamental freedom under Article 19(1)(a) can be reasonably restricted only for the purposes mentioned in Article 19(2) and the restriction must be justified on the anvil of necessity and not the quicksand of convenience or expediency . Open criticism of government policies and operations is not a ground for restricting expression.

“We must practice tolerance of the views of others.Intolerance is as much dangerous to democracy as to the person himself.“

It was re-emphasised by the SC in S Khushboo vs Kanniamal [2010 (5) SCC 600].It had said that right to freedom of speech and expression, though not absolute, was necessary as we need to tolerate unpopular views.This right requires free flow of opinions and ideas essential to sustain the collective life of the citizenry . While an informed citizenry is a precondition for meaningful governance, the culture of open dialogue is generally of great societal importance.

So far so good. But, there is a flip side to this tolerance debate. If a person belonging to a majority community rejected an invitation for a religious function conducted by a per son from minority community, he would be branded intolerant. But, if we just reverse the characters, then the action of the person from minority community would be treated as legitimate since he had the right to freedom of religion.

If a person from majority community prefers to study Sanskrit or any ancient Hindu subject, he would be branded obscurantist and even fundamental. But, if he decides to study German, French, Japanese or any other foreign language, then he would be bracketed with those having progressive outlook. That is the reason probably why we have eminent Indologists from foreign countries.

Tolerance is a double edged sword. When Kirt Azad was suspended for al leged anti-party activities by BJP, there was a chorus by Congress and AAP terming the action undemocratic, tha it smacked of intolerance.

But, in November, AAP had suspended its own MLA Pankaj Pushkar from the as sembly for raising an issue that did not grab eyeballs on social networking sites -economically weaker category in schools.

Last month, Congress sacked the editor of its mouthpiece for publishing articles that intended to praise its president Sonia Gandhi but contained a line that her father had links with fascists in Italy. It is easy to ad vocate tolerance and free speech, but rules take a somersault when it comes to self.

Constitutional provisions

Restrictions specified under Article 19(2)

The Times of India, Aug 10 2015

Dhananjay Mahapatra

Freedom of speech and expression guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution has long been regarded as the second most important after the right to life of a citizen. In recent times, it appears to be the most misused right in India, especially on the internet. Take, for example, the Yakub Memon hanging case.Views expressed on the issue were sharply divided on merits and veered to religious lines. It led to clash of ideologies, open spats, painting those who favoured execution as `bloodthirsty' and those who opposed it as `traitors'.

Freedom of speech on the internet is scaling new internet is scaling new heights every day with complete disregard for the restrictions specified under Article 19(2). Netizens are always in a rush. They post their views the moment they come across a statement.Mostly , it either gets a thumbs up or derisive criticism. The degree of controversy attached to an issue increases the severity of cuss words.

If one advocates stay of hanging of a terrorist, he gets slammed as a left-leaning activist fed on foreign funds. If one argues for the hanging, the `activists' slam him as a bloodthirsty rightwinger. By indulging in such slanderous accusations, ostensibly in exercise of right to freedom of speech, are the two groups not infringing upon the right to life of each other? For, right to life includes a life with dignity .

People may not agree with each other on a certain issue, but does it prevent them from being civil and secular while expressing their views? If a person has objection to such abuse on internet, does he have an effective legal remedy? Is it not cumbersome and a waste of time to go after those who use cuss words? And was this the intention of the Constitution-framers, and later the Supreme Court, to give such wide meaning and interpretation to freedom of expression?

In Shreya Singhal case, the Supreme Court recognized the problem that could arise if every person aggrieved by abusive criticism of his view on the internet was to make a request directly to the service provider to take down the offending comments.

It had read down Section 79(3)(b) of the Information and Technology Act contemplating action against service providers for abusive comments on websites hosted by them. It had said such action could be taken against the service provider only if it failed to comply with the court order directing it to take down the material which had been held to be abusive or offensive on the basis of a complaint. “This is for the reason that otherwise, it would be very difficult for intermediaries like Google, Facebook etc to act when millions of requests are made and the intermediary is then to judge as to which of such requests are legitimate and which are not,“ it had said.

But who will have the time and energy to pursue a case in a court of law by filing a complaint against persons who used abuses to criticize his view? The type and kinds of names under which comments are posted on websites these days would make it extremely difficult for a complainant to find out the actual name and address of the author who violated his dig nity and reputation. And when there is a systematic group attack against a view, it is better for the person to silently stomach the abuse.

The absence of protection against abuses, invectives and cuss words expressed freely to register dissenting view is the deterrent for many in society from using their real names to express views on the internet.

In a recent judgment on the criminality of a poet in using Mahatma Gandhi as a fictitious character and attributing abusive words to him to depict society , the Supreme Court said freedom of speech did not protect the poet from facing trial under Section 292 of Indian Penal Code for indulging in obscenity .

Justice Dipak Misra, writing the judgment in Devidas Ramachandra Tuljapurkar case, said a poet was “free to depart from the reality; fly away from grammar; walk in glory by not following the systematic metres; coin words at his own will; use archaic words to convey thoughts or attribute meanings; hide ideas beyond myths which can be absolutely unrealistic; totally pave a path where neither rhyme nor rhythm prevail; can put serious ideas in satires, notorious repartees; take aid of analogies, metaphors... and one can do nothing except writing a critical appreciation in his own manner and according to his understanding“.

Despite this poetic licence for freedom speech and expression, the SC was clear that “a person's human dignity must be respected, regardless of whether the person is a well-known figure or not“. But except for moving court against rogue elements on the internet, does a person aggrieved by a torrent of abuse have an immediate remedy? The time is ripe for legislators to think about it.

The arts: Banning works of art

The Indian SC: Mixed record on bans

The Times of India, Sep 15 2015

Manoj Mitta

To bar or not to bar: SC has mixed record

For all its claims to being a sentinel of liberty , the Supreme Court has a mixed record in responding to various bans challenged before it over the years. Though the positions it took on bans on goat slaughter, cow slaughter, homosexuality and religious conversions are far from liberal, the best precedent that can perhaps be applied to the current dispute arising from Maharashtra's meat ban is from the same state. It was a 2013 SC judgment lifting the ban on dance bars in Maharashtra. But then, the very next year the state assembly passed a fresh law re-imposing the ban, avoiding this time the legal infirmity of discriminating between ordinary dance bars and those run in luxury hotels. The blanket ban on dance bars is liable to be struck down on the ground of violating the fundamental right of owners and employees “to practice any profession or to carry on any occupation, trade or business“, an issue that was very much reflected in the SC verdict.

This fundamental right enshrined in Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution is, not surprisingly , central to the petition filed by the Bombay Mutton Dealers Association challenging the Maharashtra government's decision to prohibit not just the slaughter of goats but also the sale of mutton for some days in deference to the Jain festival of fasting, Paryushan.

Further, the meat ban decision, like the one related to the dance bars, involves a glaring issue of discrimination too. For, the ban does not extend to the sale of fish.And, as has been widely reported, all that the government counsel could say in the Bombay HC in defence of the discrimination was that there was no slaughter in the case of fish as they would automatically die once they were taken out of water. The wishy-washy explanation has exposed the legal vulnerability of the meat ban, which has political and communal overtones.

All the same, the partisans of the Mumbai meat ban may fancy their chances because of a 2008 SC verdict upholding a similar restriction in Ahmedabad. Even there, the meat ban was in deference to the same Jain festival and the challenge came from the local lobby of butchers. To validate the meat ban in Ahmedabad, the SC had to overrule the Gujarat HC.

Such illiberal rulings from the SC are found on other kinds of bans too. Take its 2005 judgment reversing its own position on the vexed issue of cow slaughter. Way back in 1958, the SC had held that the ban on cow slaughter envisaged by Article 48 did not extend to the cattle that was “not capable of milch or draught“. As a result of the 1958 verdict, various states had allowed the slaughter of cattle that could be classified as “useless“. But all this changed in 2005 when the same SC ruled that the Article 48 ban extended to all the cattle, irrespective of their age and the strain they put on the availability of fodder.

Another blow struck by the SC to liberty was in 2013 when it reinstated the ban on homosexuality . This was a reversal of the historic judgment passed by the Delhi high court in 2009 reading down Section 377 IPC to exempt consensual sex between adults of the same gender from any criminal liability. The Supreme Court verdict of 2013 put the clock back as it re-criminalized all homosexual acts, in effect privileging public morality over constitutional morality .

Similarly , the SC took a retrograde view on laws banning religious conversions.In keeping with the right to propagate religion guaranteed by Article 25, the laws passed by some of the states forbade only those conversions that were based on coercion or fraud. Contrary to the debates held in the Constituent Assembly , the SC held in 1977 that the right to propagate religion did not confer a right on anybody to convert others. While allowing efforts to spread the tenets of a religion, the apex court ruled that anybody engaged in conversion was automatically liable to be punished, even if it was not based on any extraneous considerations.

Insulting comments: SC upholds ban on book against Islam

From the archives of The Times of India 2010

The SC said it was more concerned with peace in society than a person’s fundamental right to freedom of speech and upheld a Maharashtra government ban on a book titled “A Concept of Political World Invasion by Muslims”.

Petitioner R V Bhasin had challenged Maharashtra’s decision four years after the publication of the book to ban it on the ground that it perpetrated hatred. The Bombay HC had said that government committed no wrong by banning the book. “The way this sensitive topic is handled by the author, it is likely to arouse the emotions and sensibilities of even strong minded people... criticism of Islam is permissible like criticism of any religion and the book cannot be banned on that ground...But the author has gone on to pass insulting comments.”

Defamation, contempt employed to stifle free speech

Dhananjay Mahapatra, August 19, 2019: The Times of India

Justice A P Shah reacted sharply to TOI’s August 5 article “Preaching retired Judges seldom look back at their conduct during judgeship”. It had quoted his July 28 speech, in which he discussed a sexual harassment complaint against present CJI with a caveat “without going into the truthfulness or falsity of the complaint”. The woman had filed the complaint with help from advocates Prashant Bhushan, Shanti Bhushan, Vrinda Grover and India Jaisingh.

Citing Justice Shah’s caveat, we discussed a 2008 complaint filed by lawyers against him. We took care not to publish graphic details of the complaint and gave just an outline of the contents. Justice Shah termed it as insinuation and mildly threatened us with defamation.

To recall, it was Justice Shah who, while giving a lecture at a journalism school at Chennai in May 2017, had said, “Where the offence of defamation tends to be used against the press most often by public authorities, and increasingly powerful private players, there is one tool that is used often by courts. This is the tool of contempt of court.” Let us see how activists skilfully use both defamation and contempt to their advantage.

He delivered Rosalind Wilson Memorial Lecture titled ‘Judging the Judges’ on July 28. There was frantic messaging from advocate Prashant Bhushan’s office to reporters to attend “an important lecture by Justice A P Shah at IIC”. This was followed by a soft copy of Justice Shah’s lecture being mailed by Bhushan’s office to each newspaper reporter.

Justice Shah retired as chief Justice of Delhi High Court in February 2010. It was common corridor gossip that then most senior Supreme Court Judge, S H Kapadia, was firmly opposed to Shah’s appointment as an SC Judge. When we wrote that it was the little known 2008 complaint by a group of lawyers which probably stalled his elevation, Justice Shah asked how did we get a copy of that letter. Do free speech advocates entertain questions about source of information? Months before Justice Shah retired and when it appeared that his chances of getting appointed as a judge of the SC were bleak, advocate Prashant Bhushan in an interview to web portal ‘Tehelka’, run by Tarun J Tejpal, alleged that half of the previous 16 CJIs were corrupt but conceded that he did not have proof to back his insinuation.

Bhushan also made a serious imputation against Justice Kapadia by alleging misdemeanour with regard to hearing of a matter relating to Sterlite Group of companies, in which Justice Kapadia had certain shares. What Bhushan deliberately omitted to mention was Justice Kapadia had revealed his shareholding in Sterlite to the counsel appearing for parties during the hearing. The counsel had categorically stated that they had no objection whatsoever to the matter being heard by Kapadia.

On a contempt petition filed by amicus curiae and senior advocate Harish N Salve, the SC issued notice to Prashant Bhushan and Tehelka. Senior advocate Ram Jethmalani appeared for Prashant Bhushan. Shanti Bhushan represented Tehelka. Both requested the SC to close the proceedings claiming that it was free speech of Bhushan junior. They argued that contempt proceedings should be invoked and exercised with utmost caution so as not to infringe upon right to free speech.

On July 14, 2010, a three-judge bench of the SC in ‘Amicus Curiae vs Prashant Bhushan and Another’ rejected arguments of Jethmalani and Bhushan senior and decided to proceed with the contempt matter. It posted the matter for arguments on November 10, 2010.

On September 16, 2010, Shanti Bhushan decided to transform himself from contemner’s counsel to a contemner. In the pending contempt case against his son, he filed an application saying in writing exactly what his son had alleged leading to initiation of contempt proceedings. Bhushan senior dared the SC to send him to jail for contempt.

Like son, the father gave no proof except telling the SC that he had interacted with two former CJIs who had confided in him that their immediate successors and predecessors were corrupt.

This is how the activists operate. When they allege something, that has to be taken as gospel truth. No one dare ask for proof. If anyone seeks proof, they will bring their ilk to the courts and streets, use free speech and shout down their critics.

They will always advocate end of defamation law citing it to be an impediment to free speech. But, if someone alleges something against them based on a complaint, then they won’t flinch to threaten defamation action. And, when they reject allegations against them with ‘the contempt it deserves’, everyone is duty-bound to bury these under layers of carpets.

Remember Best Bakery case of 2002 post-Godhra riots period? Gujarat’s Modi government was branded as ‘modern day Nero’ by the SC on the basis of a petition filed by ‘Citizens for Justice and Peace’ through activist Teesta Setalvad. She had cited riot victim Zahira Sheikh’s evidence to drive home unimaginable brutalities unleashed by rioting mobs.

After Zahira was paraded all over to make a villain out of the Modi government, she lost her value as an asset worth nurturing. When denied of her share in the cake, Zahira accused Setalvad of financial irregularities in handling of money raised for riot victims. Zahira ended up in jail.

SC-appointed SIT headed by R K Raghavan once filed a sealed cover report claiming that Setalvad and her associates were tutoring witnesses and making them sign identical statements as evidence in riots cases. The SIT report, furnished in sealed cover to the SC, also mentioned about how Setalvad and her team were circulating exaggerated stories of violence against Muslims.

When TOI reported this quoting the sealed cover SIT report, it was denied by Setalvad as a news story based on briefing of the Gujarat government. When TOI quoted pages of the SIT report which were caustic about Setalvad’s activities, she through activist lawyer Indira Jaising moved the SC seeking initiation of contempt proceedings. How could the TOI access sealed cover SIT report was their wounded refrain. Does it not sound similar to Justice Shah’s question — how did the reporter get the 2008 complaint copy?

Fortunately, a three-judge bench of the SC did not entertain Jaising’s arguments for initiation of contempt proceedings for reporting the SIT report. Right to free speech after all is double-edged. It is available as much to the activists as to commoners.

SC: No poetic licence to make Bapu swear

The Times of India, May 15 2015

Dhananjay Mahapatra

The Supreme Court ruled against poetic licence stretching the right to freedom of expression to cast revered figures like Mahatma Gandhi as a character in a fictional work and attributing obscene words to him.

A bench of Justices Dipak Misra and P C Pant upheld the prosecution launched against Devidas Ramachandra Tuljapurkar, editor of magazine `Bulletin' meant for private circulation among members of the All India Bank Association Union, for the poem `Gandhi Mala Bhetala' (I met Gandhi). The poem, written by Vasant Dattatreya Gurjar, was published in the July-August 1994 issue of the magazine. However, it discharged the printer and publisher as they had tendered apologies.

The judgment, authored by Justice Misra, dealt exhaustively with the issue of obscenity , referred to works of famous authors and poets across the world, extracted passages from 40-odd books on Gandhi written by Indians and foreigners and tested poetic licence on the touchstone of `contemporary community standards'.

The question before the court was “whether in a write-up or a poem, keeping in view the concept and conception of poetic licence and the liberty of perception and expression, using the name of a historically respected personality by way of allusion or symbol is permissible“? Using his educational background in literature, Justice Misra dug deep into the works of famous authors to convey what poetic licence was intended to serve and whether using historically revered figures as characters in a poem and attributing obscene words to them served that purpose. Tuljapurkar had claimed that he used the obscene words, as if spoken by Gandhi, to convey the angst in society. He faces prosecution under Section 292 of IPC, which is punishable by upto five years in jail.

The bench accepted sub missions of amicus curiae Fali S Nariman, who said, “Words that had been used in various stanzas of the poem, if spoken in the voice of an ordinary man or by any other person, it may not come under the ambit and sweep of Section 292, but the moment there is established identity pertaining to Mahatma Gandhi, the character of the words change and they assume the position of obscenity .“

The SC said, “Freedom of speech and expression has to be given a broad canvas, but it has to have inherent limitations which are permissible within the constitutional parameters.“ An author's fallacy in imagination could not be attributed to historically revered figures to diminish their value in the minds of people, the bench said. If an author used obscene words and attributed it to such personalities, then he travelled into the field of perversity , it added.

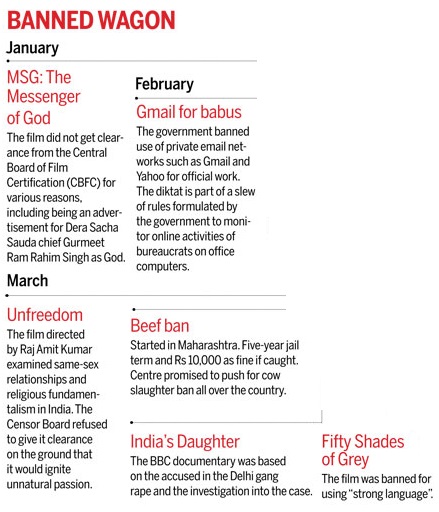

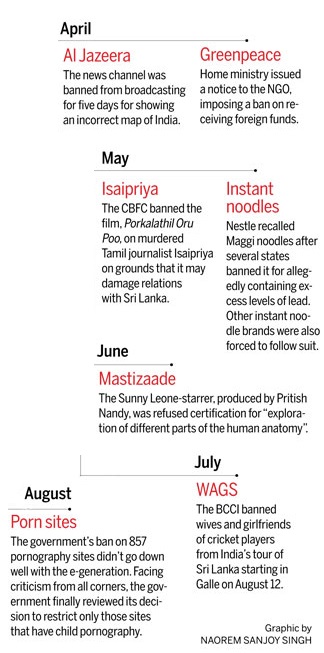

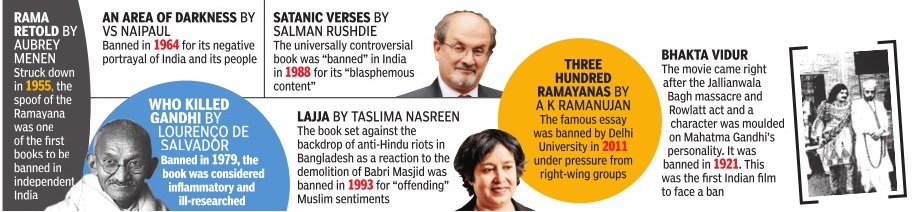

Bans in 2015

India Today, August 6, 2015

Damayanti Datta

Religion, politics and sex. Caught between the trinity, Independent India has managed to silence several voices and opinions. While the recent uproar over the ban on porn sites forced the government to retract, check out the milestones of our long heritage of intolerance.

Religion, politics and sex. Caught between the trinity, Independent India has managed to silence several voices and opinions. While the recent uproar over the ban on porn sites forced the government to retract, check out the milestones of our long heritage of intolerance.

5 times the Supreme Court restored our faith in justice in July 2015

July 30

MIDNIGHT HEARING

For the first time, the Supreme Court was opened at 2 a.m. for a three-judge bench headed by Justice Dipak Misra to hear the final plea of 1993 Bombay blasts convict Yakub Memon, a few hours before his execution.

July 30

TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY

A bench of Justices Anil R. Dave and Kurian Joseph allowed a minor rape victim to terminate pregnancy after 24 weeks, making an exception to the rule which allows abortion until the 20th week of pregnancy.

July 8

BAN ON PORNOGRAPHY

The Supreme Court said India can't ban porn. Chief Justice of India H.L. Dattu said a total ban on sex sites would violate privacy and personal liberty.

July 6

RIGHTS OF UNWED MOTHERS

An unwed mother can be the sole guardian of a child without prior consent of the biological father, ruled Justice Vikramajit Sen.

July 1

MEDICAL NEGLIGENCE

Justices J.S. Khehar and S.A. Bobde ordered Tamil Nadu government to pay Rs 1.8 crore, one of the largest compensations in a medical negligence case, to an 18-year-old girl who lost her vision at birth in a government-run hospital. 10 films that faced the ire of government, censor board and a prudish society.

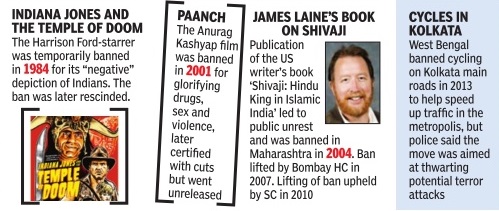

The case of Padmaavat, the film

SC invokes right to freedom of speech, tells governments to douse threats

From: Dhananjay Mahapatra, SC rescues Padmaavat, orders 4 states to lift ban on screening, January 19, 2018: The Times of India

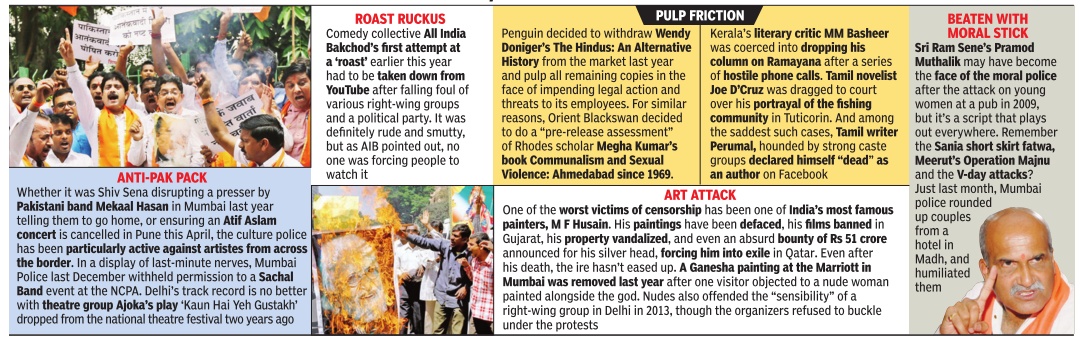

See graphic:

The case of Padmaavat, the film: observations of the Supreme Court

‘Govts’ Duty To Tackle Threats Of Violence’

Invoking the constitutionally guaranteed right to freedom of speech and expression and reminding governments of their constitutional obligation to douse threats of violence, the Supreme Court on Thursday cleared the countrywide release of controversial film “Padmaavat” on January 25.

Though this is an interim order from the Supreme Court which will hear the petition again on March 26, its effect was that of a final order given the detailed discussion about the sanctity and inviolability of right to freedom of speech and expression.

Hearing a petition from the producers and the director of the film, banned by the BJP-ruled states of Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Haryana, the bench led by CJI Dipak Misra reminded the states of their constitutional obligation to protect right to free speech and expression by controlling law and order problems that could arise because of opposition to screening of the film by fringe groups. It effectively struck down the ban by the four states.

Spectre of fear can’t be allowed to prevail: SC

The bench of CJI Misra and Justices A M Khanwilkar and D Y Chandrachud needed very little persuasion from senior advocate Harish Salve to fault the four states for refusing to screen the film even after changes, including in the title from ‘Padmavati’ to “Padmaavat’, were made at the behest of the Central Board of Film Certification. The CBFC cleared the film with a U/A certificate.

However, the four states, through additional solicitor general Tushar Mehta, argued that the CBFC, while clearing a film, scrutinised filmmaking and ethical aspects but state governments had to factor in possible law and order challenges arising from volatile social dynamics.

The argument was junked by the CJI. “That is the fundamental error. If the film ‘Bandit Queen’ can pass the test of the SC, why not ‘Padmaavat’? Whether a film is a box office bomb or a flop, whether distributors buy the film or not, we are not concerned. When the right to freedom of speech and expression, which is inseparable from making a film or enacting street theatre, is guillotined, my constitutional concern gets aroused. Artistic and creative expressions have to be protected,” he said.

“A spectre of fear cannot be allowed to prevail under the Constitution,” the bench said, asserting that in a country governed by rule of law, fringe groups could never be permitted to hold filmmakers to ransom. It recalled the apex court’s judgment clearing the release of Prakash Jha’s film ‘Aarakshan’ to tell all states, especially the four which have banned ‘Padmaavat’, to discharge their constitutional obligation and deal firmly with law and order issues.

The bench rejected Mehta’s plea for adjournment and said, “There are valuable constitutional rights involved. If we adjourn this case without passing interim orders, it will be wrong.” It cited how the controversial Marathi play ‘Mi Nathuram Godse Boltoy’ by Pradip Dalvi, or film ‘Mohan Joshi Haazir Ho’ by Saeed Mirza were allowed to be exhibited despite their controversial themes. The only assurance the states got was that the court would reconsider its interim order if they could later establish they had the supreme legal right to ban screening of a particular film because of apprehensions of law and order problems.

Lively discussion among the judges and lawyers

The proceedings in the Supreme Court challenging the ban on ‘Padmaavat’ by four states saw a lively discussion among the judges and lawyers on dogmas and the Victorian mindset of governments which have impeded the reading of classics, movie based on sensitive issues and staging of plays.

On the table were classics like Kalidasa’s ‘Meghadoota, love story from Mahabharata on ‘Nala and Damayanti’, ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’, ‘Gandhi: Naked Ambition’ by Jad Adams and ‘Man Who Killed Gandhi’. The controversial plays which were brought up and elicited caustic comments from the CJI Dipak Misra-led bench included Pradip Dalvi’s Marathi play ‘Mi Nathuram Godse Boltoy’ and Vijay Tendulkar’s ‘Sakharam Binder’.

Films that found mention were Shekhar Kapoor’s ‘Bandit Queen’, Prakash Jha’s ‘Aarakshan’ and K A Abbas’s ‘Tale of Four Cities’. The CJI also cited the artistic freedom that flows in street plays, theatre, drama and ‘geeti natyas’ (dance dramas) popular in the hinterland.

Justice Misra said a puritan Odia scholar had translated ‘Nala and Damayanti’ into the regional language in 1884 while omitting certain stanzas saying it was not appropriate for readers to digest. “He had a perception befitting that of the Victorian era. Just imagine how Kalidasa could get away with Meghadoota in that era. We need to evolve and understand the importance of right of free speech. If we apply Victorian era mindset, then I have no hesitation in saying that 60% of the classics would not be available for reading,” the CJI said.

This provided the opening for senior advocate Harish Salve to argue that artistic expressions must be given liberal licence. “The film ‘Padmaavat’ has no distortion of history and is based on the famous epic of the same name written in 1540 by well known Sufi poet Malik Muhammad Jayasi. But one day, I would love to argue how artistic expressions can have licence to distort history.”

Salve said the western world had made ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’, a 1970 rock opera with music by Andrew Lloyd Webber and lyrics by Tim Rice. The work was loosely based on the gospels’ accounts of the last week of Jesus’s life, beginning with preparations for the arrival of Jesus and his disciples in Jerusalem and ending with the crucifixion.

Not intending to widen the debate to areas unconnected with ‘Padmavaat’, the bench said, “Let us not get into that territory.” But additional solicitor general Tushar Mehta said artistic freedom of expression could never be a licence to distort history. “Can anyone in India be permitted to make a film showing Mahatma Gandhi sipping whisky?,” he said.

The bench said the Central Board of Film Certification, which is the statutory body under the Cinematograph Act, 1952, to clear films for public exhibition, was bound to examine all scenes in a film and delete those denigrating or degrading women.

Mehta said, “The question on this film is not about denigrating or degrading a woman. Here, it is not just a woman. She is treated like a goddess and worshipped. It is not a simple gender issue to be dealt by the CBFC... Suppose a film has humour about a particular community which is in majority in a state. Can the state not order suspension of screening of that film to avert law and order situation?”

Meesha: Imagination of artists must be unfettered SC

Throwing out a petition seeking ban on Malayalam novel “Meesha’ that allegedly portrayes priests and young girls in bad light, the Supreme Court on Wednesday put its weight behind the right to freedom of expression of writers and artists, saying their thinking, musings and imaginations must be unfettered.

A bench of Chief Justice Dipak Misra and Justices A M Khanwilkar and D Y Chandrachud said: “It has to be kept uppermost in mind that the imagination of a writer has to enjoy freedom. It cannot be asked to succumb to specifics. That will tantamount to imposition. A writer should have free play with words, like a painter has it with colours. The passion of imagination cannot be directed.”

Writing the judgement for the bench, CJI Misra said: “True it is, the final publication must not run counter to law but the application of the rigours of law has to also remain alive to the various aspects that have been accepted by the authorities of the court. Craftsmanship of a writer deserves respect by acceptance of concept of objective perceptibility.”

Quoting French writer Voltaire’s famous line - “I may disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it”-, the CJI dismissed the petition by N Radhakrishnan seeking a ban on the book and said, “If books are banned on such allegations, there can be no creativity. Such interference by constitutional courts will cause death of art.” The SC sent a reminder to all those who show intolerance towards novels on the ground that it offended religious or social sentiments of people by saying: “We must remember that we live not in a totalitarian regime but in a democratic nation which permits free exchange of ideas and liberty of thought and expression.”

“The flag of democratic values and ideals of freedom and liberty has to be kept flying high at all costs and the judiciary must remain committed to this spirit at all times unless they really and, we mean, really in the real sense of the term, run counter to what is prohibited in law. And, needless to emphasise that prohibition should not be allowed entry at someone’s fancy or view or perception,”

Censorship of art, cinema etc

See

Censorship of the arts and media: India

Electronic platforms: Internet, cellphones

Gujarat HC upholds mobile internet curfew during Patel stir

The Times of India, Sep 19 2015

Says the ban was `just and proper'

The Gujarat high court has upheld the state government's decision to impose a week-long mobile internet ban in August 2015 when riots broke out on August 25 following the arrest of Hardik Patel, the torchbearer of the ongoing Patidar reservation stir. Terming the ban “just and proper“, the court turned down a PIL filed by law student Gaurav Vyas, who had challenged the blocking of mobile internet services on the ground that it violated fundamental rights. Vyas had also questioned the city police commissioner's invocation of CrPC's Section 144 (power to issue orders in urgent cases of nuisance or apprehended danger) to restrict mobile internet services.

The petitioner contended that the government should have blocked certain websites or services by applying Information Technology Act's Section 69A (blocking content in case security of state is threatened). “Applying Section 144 of CrPC to block internet is arbitrary and beyond the scope of the provisions of the law,“ he argued in his plea.

In response, the government submitted that there was sufficient and valid ground to exercise CrPC's Section 144 to block mobile internet services, as “it would have been difficult to restore peace otherwise“. The state government also submitted that the exercise of power was not extreme since internet was still accessible on broadband and Wi-Fi services.

After hearing the case, the court said Section 144 of the CrPC was exercised for preventive action. In a given case, Section 69A of the IT Act might be exercised for blocking certain websites, whereas directions could be issued under CrPC provisions to service providers to block internet facilities. The petitioner's advocate said they planned to move the SC against the HC order.

Fake news

What is Fake news?

The Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) has rightly directed the information and broadcasting (I&B) ministry to withdraw its statement issued on Monday announcing new guidelines to govern the accreditation of journalists if they were found indulging in fake news. The directive follows all-round criticism and apprehensions that the new rules could in effect be misused to curb press freedoms.

While the move has now been reversed, the fact is that enough safeguards against misleading or false news by media personnel already exist within current laws. Organizations like the Press Council of India (PCI), for newspapers, and News Broadcasters Association, for television channels, already exist to ensure press accountability.

It is important to distinguish here between fake news — created and disseminated consciously despite full knowledge of it being false — and inaccurate reporting where errors in news coverage sometimes creep in by mistake, but without any malintent. Such errors can always be corrected and it is important to define fake news accurately. The Editors Guild or NBA can do this. It should not be done by government.

Though the now-withdrawn new rules would have affected only a small number of journalists ( 2,403 currently registered with Press Information Bureau), there were three broad problems with this.

› First, that any journalist who had a complaint registered against her would automatically have had their accreditation cancelled, till a regulating agency decided on the matter. Since anyone can file a complaint, this, it was rightly feared, would open the route for misuse.

› Second, the vast majority of fake news is created online by vested interests who want to propagate shifts in public opinion by manufacturing false news. This includes politicians and those supported by political parties, who also deploy vast resources online to then propagate these manufactured messages. These regulations would not have covered these fake news creators.

› Third, to guard against misuse, the definition of fake news itself must only be regulated by and enforced by industry self-governing industry bodies like PCI, NBA or the Editors Guild, not by government.

What exactly is fake news?

Fake news is ‘news’ that’s been created knowing it isn’t true. Unlike inaccurate reporting, which newspapers by and large correct and/or apologise for, fake news isn’t accidental or a genuine mistake. It isn’t even bias. It’s plain false and purposefully crafted to mislead.

Take the case from some years ago, when a piece of fake news about Kiran Bedi gained traction, when she was named the opposition BJP candidate for Delhi chief minister. If not directly her political opponents, people who generally wanted to create an unfavourable impression about her spread the canard that Bedi was not India’s first woman police officer and that her proclamations that she was were false. Fact is, she was indeed India’s first woman police officer, but so convincing was a fake news clip that was generated, that it fooled even seasoned news watchers.

There is no universally acknowledged definition of fake news. A recent paper, ‘The Science of Fake News’ published in the journal ‘Science’ defined fake news as “fabricated information that mimics news media content in form but not in organisational process or intent”.

Another definition was provided by Claire Wardle of First Draft, a UK-based nonprofit organisation that is part of the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. In an article entitled “Fake News. It’s Complicated”, she categorised misinformation or disinformation into seven categories, namely satire or parody, misleading content, imposter content (where genuine sources are impersonated), fabricated content, false connection (where headlines, visuals or captions don’t support the content), false context (where genuine information is shared with false contextual information) and manipulated content (where genuine content is manipulated in order to deceive).

Are all forms equally problematic?

If we look at the categories spelt out, it is quite clear that they aren’t all equally harmful or malicious. It is important, therefore, to distinguish for instance between improper contextualization, which could be poor journalism, and downright false content. The key question that needs to be asked is whether there is a deliberate attempt at providing false information. Obviously, even within this, the possible consequences of the false information getting spread would make a difference to how seriously the breach ought to be viewed.

Is it a product of social media?

Fake news is by no means a new phenomenon. However, the existence of social media has some clear effects on the problem. For one, the reach of social media is so much wider than traditional forms of media that the spread of fake news (as also true news) is much greater today than in past. Secondly, while traditional media operated to fixed deadlines, like a 24-hour cycle for daily newspapers or an hourly cycle for TV news bulletins, social media is a real time medium. That makes it more likely that unverified content will get spread. Finally, unlike with traditional media where the recipient knew very clearly who the provider of the ‘news’ was, the original source can become anonymous in social media. What all of this means is that it is easier to purvey fake news today and to make it reach far in a very short while.

Shouldn’t action be taken against purveyors of fake news?

Once we accept that the term is a catch-all that covers a very wide spectrum of misleading or false information, it follows that how we deal with each of these has to be different. We must make a distinction between genuine errors or incompetence on the part of journalists and clear attempts to spread falsehoods. We also need to take into account the potential for harm from such ‘fake news’. Allowing governments to determine what is or is not fake news and to punish the errant journalists has obvious risks. It would become all too easy for governments to muzzle the media by using this stick as a threat. It must, therefore, be left to regulators that are autonomous of the government, whether like the Press Council of India, or the National Broadcasters Association. For sections of media that do not have such regulators, they will need to be put in place.

Freedom to criticize religions

See Freedom to criticize religions: India

Hate speech

Definition, debate

The Times of India, Oct 05 2015

In India, there is no law that defines hate speech

What is hate speech?

Hate speech is a term used for a wide range of negative discourse linked with the speaker's hatred or prejudice against a certain section of society . It could be degrading, intimidating and aimed to incite violence against a particular religion, race, gender, ethnicity , nationality , sexual orientation, disability, political views, social class and so on. History has many examples when hate speeches were used to trigger eth nic violence resulting in genocide, as happened with the Jews in Nazi Germany and the Tutsi community in Rwanda.Regulation on hate speech is a post-Second World War phenomenon.

Isn't restriction on free speech unconstitutional?

Issues related to hate speech are often countered with the argument about freedom of speech. Given India's diversity , the drafters of the Constitution felt it was important to ensure a culture of tolerance by putting some restraints on freedom of speech. Sub-clause (a) of clause 1 of Article 19 of the Constitution states that all citizens have the right to freedom of speech and expression. However, it also states that the state can put reasonable restrictions on the exercise of this right in the interest of sovereignty and integrity of the country , security of state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency and morality and in rela tion to contempt of court.

What are the laws against hate speech in India?

Various sections of IPC deal with hate speech. For instance, according to Sections 153A and 153B, any act that promotes enmity between groups on grounds of religion and race and is prejudicial to national integration is punishable. Section 295A of IPC states that speech, writings or signs made with deliberate intention to insult a religion or religious beliefs is punishable and could lead to up to three years of jail. Simi larly the Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955, which was en acted to abolish untouchabili ty, has provisions penalising hate speech against Dalits. De spite the existence of all these laws, the Supreme Court in March 2014 asked the law com mission to suggest how hate speech should be defined and dealt with since the term is not defined in any existing law.

Can a community, class or caste be targeted in a political speech?

Section 125 of the Representation of the People Act restrains political parties and candidates from creating enmity or hatred between different classes of citizens of India. Also Section 123(3) of the Act states that no party or candidate shall appeal for votes on the ground of religion, race, caste, community , language and so on.

SC orders (2018, 2020), guidelines

Sunil Baghel, May 15, 2022: The Times of India

The Supreme Court of India, while hearing a clutch of petitions on hate speech, in fact, expressed unhappiness that despite two SC orders – one in 2018 and other in 2020 – laying down guidelines on hate speech, the same were not being followed by the states.

So, what exactly are the guidelines laid down by in the two Supreme Court orders?

2018: Nodal officer in each district

Hearing a public interest litigation against a series of mob-lynching incidents, the SC bench headed by then Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra said it was the duty of the states to incessantly and consistently strive and to promote fraternity amongst all citizens so that the dignity of every citizen is protected, nourished and promoted.

The bench issued numerous guidelines under three heads – preventive, remedial, and punitive. Though the guidelines were mainly on the issue of mob-lynching/mob-violence, they did cover hate speech and spreading irresponsible messages.

The court directed state governments to designate a police officer not below the rank of Superintendent of Police as nodal officer in each district. The nodal officer, assisted by one deputy superintendent of police rank officer, was supposed to constitute a special task force to gather “intelligence about people likely to commit such crimes or involve themselves in making or spreading hate speeches, provocative statements or fake news.”

The court directed that the police must register FIRs under Section 153A of the Indian Penal Code (promoting enmity between different groups on grounds of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, etc. and doing acts prejudicial to maintenance of harmony) and/or other relevant provisions of law against persons who disseminate irresponsible messages and videos which could incite mob violence.

Towards the end of the judgment, the court had the following message for the state governments: “We may emphatically note that it is axiomatic that it is the duty of the State to ensure that the machinery of law and order functions efficiently and effectively in maintaining peace so as to preserve our quintessentially secular ethos and pluralistic social fabric in a democratic set-up governed by rule of law. In times of chaos and anarchy, the State has to act positively and responsibly to safeguard and secure the constitutional promises to its citizens.”

2020: Elements of hate speech

The SC judgment of December 2020, involving a TV News anchor, contains an elaborate discussion on the concept of hate speech – mainly the distinction between hate speech and free speech, the need to criminalise hate speech and the tests to identify it. Multiple FIRs were lodged against the anchor for allegedly making remarks against Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti while holding a debate on the Places of Worship Act, 1991.

The SC Division Bench of Justices A M Khanwilkar and Sanjiv Khanna referred to an article by Alice E Marwick and Ross Miller of Fordham University, New York, and said there were three distinct elements that legislatures and courts can use to identify hate speech:

a) Content-based element

b) Intent-based element

c) Harm-based element or impact-based element

The content-based element would involve use of words and phrases generally considered to be offensive to a particular community and objectively offensive to the society. It can include use of certain symbols and iconography.

The intent-based element would require the speaker’s message to intend only to promote hatred, violence or resentment against a particular class or group without communicating any legitimate message.

The harm or impact-based element referred to the consequences of the ‘hate speech’ — harm to the victim which can be violence or loss of self-esteem, economic or social subordination, physical and mental stress or effective exclusion from the political arena. “Nevertheless, the three elements are not watertight silos and do overlap and are interconnected and linked,” the bench said.

Content, context and other variables

The court noted that not just the content of the speech, but also its context was important in determining whether it amounts to hate speech or not. It added that ‘context’ would further involve certain key variables like ‘who’, ‘what’, ‘where’ and the ‘occasion, time and under what circumstances’ the case arises.

'Content' concerned more with the expression, language and message used to vilify, demean and incite psychosocial hatred or physical violence against the targeted group.

The court also observed that the impact of hate speech depends on the person who has uttered the words. “The variable recognises that a speech by ‘a person of influence’ such as a top government or executive functionary, opposition leader, political or social leader of following, or a credible anchor on a TV show carries far more credibility and impact than a statement made by a common person on the street,” the bench said.

The court placed greater responsibility on those whose words likely carry more weight, suggesting they should be judged more harshly for irresponsible statements. “Persons of influence, keeping in view their reach, impact and authority they yield on general public or the specific class to which they belong, owe a duty and have to be more responsible. They are expected to know and perceive the meaning conveyed by the words spoken or written, including the possible meaning that is likely to be conveyed. With experience and knowledge, they are expected to have a higher level of communication skills. It is reasonable to hold that they would be careful in using the words that convey their intent,” the court observed.

‘Good faith’ and ‘(no)-legitimate purpose’ protection The court explained that ‘good faith’ conduct should display fidelity as well as a conscientious approach in honouring the values that tend to minimise insult, humiliation or intimidation.

On ‘(no)-legitimate purpose’, the court said one of the clearest markers of hate speech is that it has no redeeming or legitimate purpose other than spreading hatred towards a particular group. “A publication which contains unnecessary asides which appear to have no real purpose other than to disparage will tend to evidence that the publications were written with a mala fide intention.”

Law Commission’s recommendations

The Law Commission, in its 267th report, recommended amendments to the criminal laws for inserting new provisions prohibiting incitement to hatred by adding Section 153C.

Another addition through Section 505A to make intentionally causing fear, alarm, or provocation of violence in certain cases as an offence was also recommended. The government, however, is yet to bring about any changes in the law.

Hate news, misinformation: 2019

Oct 22, 2021: The Times of India

Internal documents at Facebook show “a struggle with misinformation, hate speech and celebrations of violence” in India, the company’s biggest market, with researchers at the social media giant pointing out that there are groups and pages “replete with inflammatory and misleading anti-Muslim content” on its platform, US media reports have said.

In a report, The New York Times said in February 2019, a Facebook researcher created a new user account to look into what the social media website will look like for a person living in Kerala.

“For the next three weeks, the account operated by a simple rule: Follow all the recommendations generated by Facebook's algorithms to join groups, watch videos and explore new pages on the site.

The result was an inundation of hate speech, misinformation and celebrations of violence, which were documented in an internal Facebook report published later that month,” the NYT report said.

“Internal documents show a struggle with misinformation, hate speech and celebrations of violence in the country, the company's biggest market,” said the report . The documents are part of a larger cache of material collected by whistle blower Frances Haugen, a former Facebook employee who recently testified before the Senate about the company and its social media platforms. The report said the internal documents include reports on how bots and fake accounts tied to the “country's ruling party and opposition figures” were wreaking havoc on national elections.

The NYT said that in a separate report produced after the 2019 national elections, Facebook found that “over 40 per cent of top views, or impressions, in the Indian state of West Bengal were fake/inauthentic”. One inauthentic account had amassed more than 30 million impressions.

In an internal document titled 'Adversarial Harmful Networks: India Case Study', "Facebook researchers wrote that there were groups and pages “replete with inflammatory and misleading anti-Muslim content” on Facebook.

The internal documents also detail how a plan “championed” by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg to focus on “meaningful social interactions” was leading to more misinformation in India, particularly during the pandemic. PTI

Information Technology Act: India

Sec 66A held unconstitutional

August 29, 2021: The Times of India

India’s ambitions of being a technological superpower in the 21st century received its biggest fillip on March 24, 2015. Till that day, its ambitions were being fuelled by the innovativeness of entrepreneurs and unstinted support of the political class that was committed, across party lines, to the lofty objective of creating a ‘Digital India’. But, as is often the case, the legal framework was behind the curve. Emblematic of its retrograde nature was the Information Technology Act. A law that was meant to promote IT had been written, wittingly or unwittingly, to achieve the opposite effect—to allow policing of conversations on the internet, arrest persons with inconvenient views and constrain the animal spirits of our entrepreneurs instead of unleashing them.

Particularly egregious was Section 66A, which criminalised communications that were “grossly offensive” or aimed at causing annoyance, inconvenience, danger, insult, injury, hatred, ill will. Using powers under this section, the police had arrested two women simply for criticising how Mumbai had been shut down when Balasaheb Thackeray died. Against any standard of good lawmaking, the problems with Section 66A and its wanton use would be considered elementary. Yet it sat smugly in our statute books, as if to demonstrate the ease with which legal rules could fly in the face of reason and constitutional rights.

Six years ago, the Supreme Court, in Shreya Singhal vs Union of India, struck down Section 66A as unconstitutional. By doing this, it stepped up to the task of reorienting India’s free speech jurisprudence to squarely face the dangers and savour the fruits of a digital age. It held out the promise of the internet being the sanctuary of the free citizen, not a playground for law enforcement agencies.

Constitutional frameworks relating to free speech regularly grapple with certain recurrent themes and issues. For what reasons can speech be restricted? How free a rein should police have in such matters? And even if a good reason for restricting speech is found, how is one to tell when that particular reason is really involved and when it is being used as an excuse? In many ways, how courts answer these questions determine how free a country actually is, as opposed to what its Constitution proclaims.

Take, for instance, the question of appropriate reasons for speech regulation: Article 19(2) of the Constitution enumerates specific reasons for restricting free speech, such as the sovereignty and integrity of the country, the security of the State, public order, and incitement to an offence. Only if these specific restrictions are attracted can speech be restricted—otherwise freedom to speak is the default rule.

But the inconsistency of Indian courts has meant this logic has often been flipped on its head. Broad excuses for speech regulation in “public interest” have made restriction the rule and freedom the exception. With the Supreme Court upholding the offence of sedition, criminal contempt and several other criminal penalties as legitimate exceptions to free speech, this zeal to restrict has only been bolstered. In this backdrop, Shreya Singhal becomes even more significant. Indian courts have often made the right noises on free speech but fallen short when it comes to ruling in favour of it. The Shreya Singhal case ensured a provision that actually restricted free speech was not merely the subject of judicial reprimand, but was wholly extinguished.

That the rot of restrictiveness that Shreya Singhal curbed ran deep is clear from the fact that wildly subjective terms such as offensiveness, annoyance, and inconvenience could even be considered acceptable in drafting laws, let alone being defended on grounds of “public interest”. Fanciful dangers and uncertainties of digital communication were held up as adequate grounds for vague rules, effectively turning the internet in India into a police fiefdom. This then constitutes yet another of Shreya Singhal’s landmark contributions: in a country where courts habitually pretend as if words do not matter, and legislators even less so, the Supreme Court placed the value of clarity of language at the centre of the framework for speech regulation. In the context of a criminal provision like Section 66A, the court demanded this clarity in the form of exacting specificity, striking down the provision for its irreparably vague terms and for its failure to constrain police action. It called out the root problem underlying not just free speech jurisprudence in India, but also one of the oldest and deepest weaknesses in its legal system: imprecision in drafting laws.

Such drafting imprecision is a byproduct of an even older and deeper malaise—governmental intransigence. A research paper by Abhinav Sekhri and Apar Gupta in 2018 shows cases continue to be filed under Section 66A despite it being struck down. A bench of the Supreme Court recently expressed its amazement as to how this could happen, leading to the Centre taking corrective measures. The lesson is clear—the arc of the legal universe may be long, but it needs more than one fell swoop to make it bend towards freedom.

This does not in any way take away from the importance of what Shreya Singhal achieved. No judgment ever fully resolves the challenges it faces up to, but posterity determines how it shapes society. The accuracy of Shreya Singhal’s diagnosis, its insistence on law being clear and its reaffirmation of the tenets of the Constitution shine through amidst the un-freedom that surrounds us. The judgment could easily have followed a safe line of precedent and sided with police forces looking to bring a lawless internet to heel. Instead, it chose freedom and all the inconvenient boisterousness that it entails. That is its abiding legacy.

Judiciary on Right to Speech and Expression

The SC’s upholding of free speech

December 24, 2018: The Times of India

‘Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron’, it is free speech; let us not whip up a controversy

In his early years, Naseeruddin Shah displayed his immense talent as an actor in films like ‘Jaane Bhi Do Yaron’, where efforts to expose corruption boomerangs, and ‘Aakrosh’, in which he as a budding advocate poignantly paints the dance of violence by the rich and powerful that grinds commoners in the Naxal-infested hinterland.

Evils of corruption and violence, stirringly depicted in these two films, continue to strip the masses of dignity, identity and livelihood. Not many make an issue of their plight. So, when Shah expressed anguish over the ‘poison’ spreading through communally violent cow vigilantism and feared for the safety of his children, he was echoing the views of filmstars Aamir Khan and Shahrukh Khan.

There is no contesting the concerns of ‘right thinking people’, for cow vigilante groups display rabid contempt for rule of law. Right to free speech, be it of actors or ‘right thinking persons’, to fearlessly condemn such wanton violence is the only way to make governments do their constitutional job — upholding rule of law without the slightest compromise.

Many ‘right thinking persons’ feel that right to free speech too is under threat even though the Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled, and as recently as on September 5 in N Radhakrishnan vs Union of India said, “A writer or an author (or any person for that matter)… has the right to exercise his liberty to the fullest unless it falls foul of any prescribed law that is constitutionally valid. It is because freedom of speech and expression is extremely dear to a civilised society. It holds it close to its heart and would abhorrently look at any step taken to create even slightest concavity in the said freedom.”

If one searches the annals of judiciary in different countries, Indian courts would emerge the undisputed leaders in zealously defending right to free speech, except for an aberration in ADM Jabalpur case [1976 (2) SCC 521] when the SC had allowed the government to muzzle it through Emergency. When celebrated artist M F Husain’s nude ‘Bharat Mata’ painting sparked violence, the Delhi High Court in its judgment through Justice Sanjay K Kaul came to Husain’s rescue. It quashed summons and warrants issued by trial courts in cases filed by groups alleging indecent portrayal of ‘Bharat Mata’.

Justice Kaul in his 2008 judgment had said, “There are very few people with a gift to think out of the box and seize opportunities and, therefore, such people’s thoughts should not be curtailed by the age-old moral sanctions of a particular section in society having oblique or collateral motives who express their dissent at the very drop of a hat.”

In contrast, the UK government had banned public exhibition of Nigel Wingrove’s 18-minute video film ‘Vision of

Ecstasy’, which was based on the life and writings of St Teresa of Avila, the 16th century Carmelite nun and founder of many convents, who experienced powerful ecstatic vision of Jesus Christ. The British Board of Film Classification said, “If the male figure were not Christ, the problem would not arise. Cuts of a fairly radical nature in the overt expression of sexuality between St Teresa and the Christ figure might be practicable but Wingrove did not wish to attempt this course of action.”

As the final arbiter, the European Court of Human Rights examined whether the UK ban violated right to freedom of expression guaranteed under Article 10 of the Convention for Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. By a 7-2 verdict, the court in 1995 upheld the ban saying the video violated UK’s strong blasphemy laws.

The Indian SC has refused to be cowed down by the display of anger and violence against films and books, be it ‘Padmavat’ or ‘An Insignificant Man’, and stoutly upheld artistic freedom. If the judiciary almost always protected freedom of speech, right thinking people remained selectively silent when macabre violence, similar to cow vigilantism, visited innocent commoners and uncorked the bottle containing the djinn of poison.

Why did they not express anguish and outrage when 59 kar sevaks were burnt alive aboard Sabarmati Express on February 27, 2002, by a mob of nearly 1,000 people in Godhra? This incident was obscured by the heart wrenching communal carnage that killed 790 Muslims and 254 Hindus in Gujarat.

The then government attempted to pull a carpet over the Godhra killings. It appointed Justice U C Banerjee Commission, which ruled out conspiracy and found it to be an internal fire. Mercifully, Gujarat HC struck down the commission’s finding. It failed to break the silence of right thinking people.

They remained silent when many Kashmiri Pandits were systematically butchered and others were forced to flee. Their numbers in the Valley rapidly dwindled, from 15% to an insignificant 0.1%. It started with Wandhama massacre in 1998, when 23 Pandit family members — four children, nine women and 10 men — were butchered by Kalashnikov-wielding Muslim militants. It was followed by massacre of 35 Hindus at Chamba by Hizbul Mujahideen. No right thinking person saw the poison spreading.