Freedom of speech: India

(→Freedom of speech should not become a licence for vilification: SC) |

(→Judiciary has continually expanded its definition) |

||

| Line 94: | Line 94: | ||

The apex court agreed with Khushboo that her comments, to a news magazine, were in response to a survey conducted about pre-marital sex in big cities in India and that it was a bona fide opinion. | The apex court agreed with Khushboo that her comments, to a news magazine, were in response to a survey conducted about pre-marital sex in big cities in India and that it was a bona fide opinion. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Freedom of speech should not become a licence for vilification: SC== | ||

| + | [http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Freedom-of-speech-should-not-become-a-licence-for-vilification/articleshow/51283347.cms ''The Times of India''], Mar 7, 2016 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Dhananjay Mahapatra | ||

| + | |||

| + | Freedom of speech and expression has never been absolute. Neither in India nor anywhere in the world. The Indian Constitution guarantees it as a fundamental right and the Supreme Court has taken pains to give it a liberal and expansive interpretation through the years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For the last one month, right to free speech has been the focus of every debate. Some students shouted certain slogans in the precincts of Jawaharlal Nehru University. It taught us the meaning of "azadi" or independence. Wish the slogans were as clear as they are being interpreted now — that the call for azadi was only from problems within the country. This is one view. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some others perceived the slogans to be abusive to the concept of India. Leaving aside the condemnable and punishable violent actions of a section of lawyers in Patiala House court, is it not possible for a section of society to hold the view that the nature of slogans raised in JNU was unacceptable? Could both these views not co-exist without there being a polarising war? | ||

| + | |||

| + | Freedom of speech has always been an instrument not to counter but to slight others, especially in the political arena. Immediately after formation of 'Indian National Congress' in 1885 headed by Womesh Chandra Banerjee, signs of muscle -flexing through speech began. The lack of importance to Muslim leaders in INC did not go down well with Sir Syed Ahmed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In an impassioned speech in Meerut in 1888, Sir Syed said, "At the same time you must remember that although the number of Mahomedans is less than that of the Hindus, and although they contain far fewer people who have received a high English education, yet they must not be thought insignificant or weak. | ||

| + | "Probably they would be by themselves enough to maintain their own position. But suppose they were not, then our Mussalman brothers, the Pathans, would come out as a swarm of locusts from their mountain valleys, and make rivers of blood to flow from their frontier in the north to the extreme end of Bengal. | ||

| + | "This thing — who, after the departure of the English, would be conquerors — would rest on the will of god. But until one nation has conquered the other and made it obedient, peace could not reign in the land. This conclusion is based on proof so absolute that no one can deny it." | ||

| + | |||

| + | How would you classify this? Free speech, political speech or a plain threat? The context in which the speech is made assumes significance in most situations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Visualise a situation. An inflammatory speech made in a remote corner of the country may escape the hawkish attention of 24x7 news television channels. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But a similar speech in the heart of the capital aired repeatedly by TV channels can have a very different effect. Irrespective of the connotations of the speech, instant politicisation takes over, making the matter worse. And, we do not yet have a definition of "inflammatory". | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is what probably happened to the speeches and slogans made in JNU. Each seamlessly used free speech to berate and denigrate the other. They freely branded opponents as anti-national or anti-Dalit. The media too got involved and divided. | ||

| + | |||

| + | JNUSU president Kanhaiya Kumar had the last laugh. After release on bail, he made an impassioned speech. But he too resorted to branding when he said, "Those in media siding with JNU are actually not speaking for JNU - they are calling a spade a spade." What did this convey, if you are not agreeing with us, then you are not speaking the truth. | ||

| + | The Supreme Court has zealously protected the right to free speech and expression through many landmark judgments - Shakal Papers (1961), Kedar Nath Singh (1962), Bennett Coleman (1972) and Indian Express (1984). | ||

| + | The SC never diluted any of the eight restrictions on free speech provided under Article 19(2), inserted through the first constitutional amendment in 1951 by the Jawaharlal Nehru government. At the same time, it never foresaw free speech acting as a catalyst for a clash of ideas or ideologies. It had hoped that free flow of ideas through free speech would make democracy more vibrant. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Kedar Nath Singh case [1962 AIR 955], the SC had said, "This court, as the custodian and guarantor of the fundamental rights of the citizens, has the duty cast upon it of striking down any law which unduly restricts the freedom of speech and expression with which we are concerned in this case. | ||

==Judiciary has continually expanded its definition== | ==Judiciary has continually expanded its definition== | ||

Revision as of 23:40, 20 April 2017

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

What is free speech?

`I Am Right, You Are Wrong' Infection Toxic

To define free speech is an arduous task. It is much easier to exerci se the right to free speech and expression guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) to all those who abide by our Constitution.

Article 19 itself constricts free speech in exceptional circumstances. But neither the Constitution nor the Supreme Court, in its numerous judgments protecting Article 19(1) (a), have given an exhaustive analysis of what free speech could be.

A middle-aged journalist was recounting his experience with free speech.He grew up in a large family where only the father had the right to free speech. Any counter argument was regarded as committing the sacrilege of talking back to father. Was his right to free speech violated?

When he had his own family, he was constantly sniped at by his children, exercising their free speech to point out how his spoken English had an awful regional accent which many a time made him prefer silence.Since evolution, family and social norms have put fetters on free speech.

The personal experience of the journalist is inconsequential when one looks at societal norms that constrict free speech. For centuries, Dalits did not have the freedom of speech to criticise upper castes. They still don't.When they decide to resort to free speech, it often invites blood-soaked humiliation. Free speech on a cricket field has in the past invited ugly spats. Free speech against judges invite contempt charges. In contrast, expletives are not part of free speech, yet it is freely used on Delhi streets. Free speech comes from free thinking, which takes place in a free environment.Has India provided a free environment that encourages free thinking? Are social norms evolved through this collective thinking conducive for free speech?

A case in point is the free articulation of one's sexual identity . The third gender cowered under the threat of prosecution and persecution for centuries. Thanks to the cases in the Delhi high court and the Supreme Court, big cities have somewhat come to terms with people going public with their sexual orientation. Still, the social stigma is so unnerving that only a few rich and famous have dared to articulate their sexual preferences.

At present, free speech has sparked a fiery debate in Delhi that refuses to be doused. A 20-year-old exercised her right to speak her mind.A legendary cricketer, who enthralled spectators with fearless batting, responded.Both these were in exercise of free speech.

But a famous lyricist muddied the free speech debate by calling the cricketer a “hardly literate player“, though he later took back his words. Is free speech the fiefdom of the so-called educated? These so-called educated use their free speech as sermons and get angry when they encounter a witty counter through free speech exercised by not so educated, yet well informed, persons. The “I am right, you are wrong“ infection has taken a virulent form during this free speech fever. Tolerance for other's right to free speech is dwindling fast.

While dealing with an incident relating to the eviction of yoga guru Baba Ramdev from Ramlila grounds in Delhi, the Supreme Court on February 23, 2012, had given one of its finest discourses on the virtues of free speech. It had said, “Freedom of speech is the bulwark of the democratic process. Freedom of speech and expression is regarded as the first condition of liberty . It occupies preferential position in the hierarchy of liberties, giving succour and protection to all other liberties. It has been said that it is the mother of all liberties. Freedom of speech plays a crucial role in formation of public opinion on social, political and economic matters.“

It will be easier to articulate the contours of free speech by referring to reasonable restrictions in Article 19 (2) and the defamation laws.But it would almost be impossible to sum up what should be the contents of free speech. Free speech, the right to exercise it by oneself and others, would be more enjoyable and informative if those participating in a debate kept in mind two words -`tolerance and fraternity’.

One must not weaken fraternity among Indians while exercising free speech, and be tolerant to others' views, even if it is a caustic counter to one's own earlier words said in exercise of free speech.

Constitutional provisions

Restrictions specified under Article 19(2)

The Times of India, Aug 10 2015

Dhananjay Mahapatra

Freedom of speech and expression guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution has long been regarded as the second most important after the right to life of a citizen. In recent times, it appears to be the most misused right in India, especially on the internet. Take, for example, the Yakub Memon hanging case.Views expressed on the issue were sharply divided on merits and veered to religious lines. It led to clash of ideologies, open spats, painting those who favoured execution as `bloodthirsty' and those who opposed it as `traitors'.

Freedom of speech on the internet is scaling new internet is scaling new heights every day with complete disregard for the restrictions specified under Article 19(2). Netizens are always in a rush. They post their views the moment they come across a statement.Mostly , it either gets a thumbs up or derisive criticism. The degree of controversy attached to an issue increases the severity of cuss words.

If one advocates stay of hanging of a terrorist, he gets slammed as a left-leaning activist fed on foreign funds. If one argues for the hanging, the `activists' slam him as a bloodthirsty rightwinger. By indulging in such slanderous accusations, ostensibly in exercise of right to freedom of speech, are the two groups not infringing upon the right to life of each other? For, right to life includes a life with dignity .

People may not agree with each other on a certain issue, but does it prevent them from being civil and secular while expressing their views? If a person has objection to such abuse on internet, does he have an effective legal remedy? Is it not cumbersome and a waste of time to go after those who use cuss words? And was this the intention of the Constitution-framers, and later the Supreme Court, to give such wide meaning and interpretation to freedom of expression?

In Shreya Singhal case, the Supreme Court recognized the problem that could arise if every person aggrieved by abusive criticism of his view on the internet was to make a request directly to the service provider to take down the offending comments.

It had read down Section 79(3)(b) of the Information and Technology Act contemplating action against service providers for abusive comments on websites hosted by them. It had said such action could be taken against the service provider only if it failed to comply with the court order directing it to take down the material which had been held to be abusive or offensive on the basis of a complaint. “This is for the reason that otherwise, it would be very difficult for intermediaries like Google, Facebook etc to act when millions of requests are made and the intermediary is then to judge as to which of such requests are legitimate and which are not,“ it had said.

But who will have the time and energy to pursue a case in a court of law by filing a complaint against persons who used abuses to criticize his view? The type and kinds of names under which comments are posted on websites these days would make it extremely difficult for a complainant to find out the actual name and address of the author who violated his dig nity and reputation. And when there is a systematic group attack against a view, it is better for the person to silently stomach the abuse.

The absence of protection against abuses, invectives and cuss words expressed freely to register dissenting view is the deterrent for many in society from using their real names to express views on the internet.

In a recent judgment on the criminality of a poet in using Mahatma Gandhi as a fictitious character and attributing abusive words to him to depict society , the Supreme Court said freedom of speech did not protect the poet from facing trial under Section 292 of Indian Penal Code for indulging in obscenity .

Justice Dipak Misra, writing the judgment in Devidas Ramachandra Tuljapurkar case, said a poet was “free to depart from the reality; fly away from grammar; walk in glory by not following the systematic metres; coin words at his own will; use archaic words to convey thoughts or attribute meanings; hide ideas beyond myths which can be absolutely unrealistic; totally pave a path where neither rhyme nor rhythm prevail; can put serious ideas in satires, notorious repartees; take aid of analogies, metaphors... and one can do nothing except writing a critical appreciation in his own manner and according to his understanding“.

Despite this poetic licence for freedom speech and expression, the SC was clear that “a person's human dignity must be respected, regardless of whether the person is a well-known figure or not“. But except for moving court against rogue elements on the internet, does a person aggrieved by a torrent of abuse have an immediate remedy? The time is ripe for legislators to think about it.

Judiciary on Right to Speech and Expression

SC: Remarks on premarital sex are Bona fide opinions

From the archives of The Times of India 2010

‘Remarks on premarital sex bona fide opinion’

There was redemption for south Indian actress Khushboo after five long years of battling 23 cases filed across Tamil Nadu against her remarks on prevalence of premarital sex in Indian cities. Putting an end to her harassment, the Supreme Court quashed all proceedings pending against her in trial courts, saying the complaints woefully lacked in evidence.

A bench comprising Chief Justice K G Balakrishnan and Justices Deepak Verma and B S Chauhan, said those who filed complaints against the 39-year-old actress were ‘‘extra-sensitive’’ about the remarks made by her in 2005 and had no proof that these had disturbed the peace or hurt people’s sentiments.

The Madras HC had on April 30 in 2014 refused to stay the proceedings in trial courts. Khushboo had introduced herself in the SC as a ‘‘famous south Indian actress, a mother of two young children’’ and said she was being harassed and victimized at the behest of people with vested interests who had filed 23 ‘‘false, frivolous and mala fide’’ complaints.

She had added that her fundamental right of freedom of speech and expression could not be curtailed by such persons.

The apex court agreed with Khushboo that her comments, to a news magazine, were in response to a survey conducted about pre-marital sex in big cities in India and that it was a bona fide opinion.

Freedom of speech should not become a licence for vilification: SC

The Times of India, Mar 7, 2016

Dhananjay Mahapatra

Freedom of speech and expression has never been absolute. Neither in India nor anywhere in the world. The Indian Constitution guarantees it as a fundamental right and the Supreme Court has taken pains to give it a liberal and expansive interpretation through the years.

For the last one month, right to free speech has been the focus of every debate. Some students shouted certain slogans in the precincts of Jawaharlal Nehru University. It taught us the meaning of "azadi" or independence. Wish the slogans were as clear as they are being interpreted now — that the call for azadi was only from problems within the country. This is one view.

Some others perceived the slogans to be abusive to the concept of India. Leaving aside the condemnable and punishable violent actions of a section of lawyers in Patiala House court, is it not possible for a section of society to hold the view that the nature of slogans raised in JNU was unacceptable? Could both these views not co-exist without there being a polarising war?

Freedom of speech has always been an instrument not to counter but to slight others, especially in the political arena. Immediately after formation of 'Indian National Congress' in 1885 headed by Womesh Chandra Banerjee, signs of muscle -flexing through speech began. The lack of importance to Muslim leaders in INC did not go down well with Sir Syed Ahmed.

In an impassioned speech in Meerut in 1888, Sir Syed said, "At the same time you must remember that although the number of Mahomedans is less than that of the Hindus, and although they contain far fewer people who have received a high English education, yet they must not be thought insignificant or weak. "Probably they would be by themselves enough to maintain their own position. But suppose they were not, then our Mussalman brothers, the Pathans, would come out as a swarm of locusts from their mountain valleys, and make rivers of blood to flow from their frontier in the north to the extreme end of Bengal. "This thing — who, after the departure of the English, would be conquerors — would rest on the will of god. But until one nation has conquered the other and made it obedient, peace could not reign in the land. This conclusion is based on proof so absolute that no one can deny it."

How would you classify this? Free speech, political speech or a plain threat? The context in which the speech is made assumes significance in most situations.

Visualise a situation. An inflammatory speech made in a remote corner of the country may escape the hawkish attention of 24x7 news television channels.

But a similar speech in the heart of the capital aired repeatedly by TV channels can have a very different effect. Irrespective of the connotations of the speech, instant politicisation takes over, making the matter worse. And, we do not yet have a definition of "inflammatory".

This is what probably happened to the speeches and slogans made in JNU. Each seamlessly used free speech to berate and denigrate the other. They freely branded opponents as anti-national or anti-Dalit. The media too got involved and divided.

JNUSU president Kanhaiya Kumar had the last laugh. After release on bail, he made an impassioned speech. But he too resorted to branding when he said, "Those in media siding with JNU are actually not speaking for JNU - they are calling a spade a spade." What did this convey, if you are not agreeing with us, then you are not speaking the truth. The Supreme Court has zealously protected the right to free speech and expression through many landmark judgments - Shakal Papers (1961), Kedar Nath Singh (1962), Bennett Coleman (1972) and Indian Express (1984). The SC never diluted any of the eight restrictions on free speech provided under Article 19(2), inserted through the first constitutional amendment in 1951 by the Jawaharlal Nehru government. At the same time, it never foresaw free speech acting as a catalyst for a clash of ideas or ideologies. It had hoped that free flow of ideas through free speech would make democracy more vibrant.

In Kedar Nath Singh case [1962 AIR 955], the SC had said, "This court, as the custodian and guarantor of the fundamental rights of the citizens, has the duty cast upon it of striking down any law which unduly restricts the freedom of speech and expression with which we are concerned in this case.

Judiciary has continually expanded its definition

The Times of India, Nov 05 2015

Arun Jaitley

Media's Right to Free Speech

India's judiciary has continually expanded the definition of this right since Independence The Constitution gave a pre-eminent position to the Right to Free Speech. Whereas, the other fundamental rights could be restricted thro ugh reasonable restrictions, the Right to Free Speech could only be restricted if the restriction had nexus with any of the circumstances mentioned in Article 19(2) of the Constitution. India's post-Constitution history is an evidence of the fact that many fundamental rights have seen their weakening in the past 65 years. The Right to Life and Liberty was literally extinguished during the Emergency . The Right to Trade has been adversely affected in the days of the regulated economy . The Right to Property was repealed during the Emergency .

However, the Fundamental Right of Free Speech and Expression has been consistently strengthened and never narrowed down. So a national policy of expanding and strengthening the right has continuously existed over a period of time.

In the initial years of the Constitution, the Supreme Court held that the excessive licence fee for starting a newspaper was constitutionally invalid.Subsequently , in the very first decade, it was held that the Wage Board imposing an unbearable burden on a media organisation, would offend Free Speech.

Can the business or commercial interest of a newspaper be segregated from the Right of Free Speech? Would the business of a newspaper fall within the domain of the Right to Free Trade or would it impact on the Right to Free Speech? In the Sakal newspaper's case, the Supreme Court was concerned with the policy imposed in 1960, wherein the government decided to regulate the selling price of a newspaper. The sale price would depend on the number of pages. The government contended that it was only restricting the Right to Trade by a reasonable restriction in consumer interest. The Supreme Court held that, if a newspaper was compelled to raise its price on account of the thickness of the newspaper it would have two consequences, either the thickness, ie, the content would be reduced or alternatively, a newspaper would be compelled to raise its price, and, there was empirical evidence to suggest that an increase in price leads to loss in circulation.Thereby, the Right to Circulate is also a part of Free Speech.

Similarly , when the government restricted the size of a newspaper on the ground that newsprint was scarce on account of paucity of foreign exchange and excessive imports would lead to an outgo of foreign exchange, the Supreme Court held that curtailing the number of advertisements in a newspaper would impact Free Speech, since advertisements themselves supplement the cost of content.

In a landmark judgment in the newsprint customs duty case, the court was confronted with the question whether imposition of customs duty on newsprint can be challenged on the ground of it being `Tax of knowledge'. The court held that the business of a newspaper could never be segregated from its content.

In the Constituent Assembly , Ramnath Goenka had raised the issue that future governments would not resort to crude methods like censorship but would pinch the pockets of the newspapers. Agreeing with this view, the court held that newspapers shape the human mind, excessive tax on a newspaper itself could impact Free Speech if the purpose of the tax was not merely to raise revenue but to excessively burden the economy of the newspaper.

In the case of any trade, business or profession, taxation would be struck down only if it is confiscatory in nature, that is, if it makes the business impossible. But in the case of a media organisation, if it adversely impacts the Right to Free Speech, that is, makes it excessively costly and prohibitive, then the tax itself can be challenged as an invasion of Free Speech.

Most other democracies have not accepted the American precedent, but we in India went ahead and accepted this particular right. I think in its entire evolution, the customs duty case in its exposition of law and expanding the right became a landmark, in that the distinction between the business of Free Speech and the right of actual content of Free Speech itself, was obliterated.

Carrying this logic further, the Supreme Court, in the Tata Yellow Pages case, included commercial Free Speech, ie, advertising, to be a part of Free Speech. This proposition is still doubtful, since it could enable `paid' news to take the benefit of commercial speech being a part of Free Speech.

Paid news is a reality , and therefore if you follow the dicta of the American judgments which Tata Press has followed in India, will Free Speech also provide a right which extends to paid news? Obviously it does not sound logical, and therefore this issue has not come up before the courts. However, if there was to be a penal provision against paid news, it would have to be tested on the touchstone of whether it violates Free Speech or not.

Hate speech

The Times of India, Oct 05 2015

In India, there is no law that defines hate speech

What is hate speech?

Hate speech is a term used for a wide range of negative discourse linked with the speaker's hatred or prejudice against a certain section of society . It could be degrading, intimidating and aimed to incite violence against a particular religion, race, gender, ethnicity , nationality , sexual orientation, disability, political views, social class and so on. History has many examples when hate speeches were used to trigger eth nic violence resulting in genocide, as happened with the Jews in Nazi Germany and the Tutsi community in Rwanda.Regulation on hate speech is a post-Second World War phenomenon.

Isn't restriction on free speech unconstitutional?

Issues related to hate speech are often countered with the argument about freedom of speech. Given India's diversity , the drafters of the Constitution felt it was important to ensure a culture of tolerance by putting some restraints on freedom of speech. Sub-clause (a) of clause 1 of Article 19 of the Constitution states that all citizens have the right to freedom of speech and expression. However, it also states that the state can put reasonable restrictions on the exercise of this right in the interest of sovereignty and integrity of the country , security of state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency and morality and in rela tion to contempt of court.

What are the laws against hate speech in India?

Various sections of IPC deal with hate speech. For instance, according to Sections 153A and 153B, any act that promotes enmity between groups on grounds of religion and race and is prejudicial to national integration is punishable. Section 295A of IPC states that speech, writings or signs made with deliberate intention to insult a religion or religious beliefs is punishable and could lead to up to three years of jail. Simi larly the Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955, which was en acted to abolish untouchabili ty, has provisions penalising hate speech against Dalits. De spite the existence of all these laws, the Supreme Court in March 2014 asked the law com mission to suggest how hate speech should be defined and dealt with since the term is not defined in any existing law.

Can a community, class or caste be targeted in a political speech?

Section 125 of the Representation of the People Act restrains political parties and candidates from creating enmity or hatred between different classes of citizens of India. Also Section 123(3) of the Act states that no party or candidate shall appeal for votes on the ground of religion, race, caste, community , language and so on.

Banning works of art

The Indian SC: Mixed record on bans

The Times of India, Sep 15 2015

Manoj Mitta

To bar or not to bar: SC has mixed record

For all its claims to being a sentinel of liberty , the Supreme Court has a mixed record in responding to various bans challenged before it over the years. Though the positions it took on bans on goat slaughter, cow slaughter, homosexuality and religious conversions are far from liberal, the best precedent that can perhaps be applied to the current dispute arising from Maharashtra's meat ban is from the same state. It was a 2013 SC judgment lifting the ban on dance bars in Maharashtra. But then, the very next year the state assembly passed a fresh law re-imposing the ban, avoiding this time the legal infirmity of discriminating between ordinary dance bars and those run in luxury hotels. The blanket ban on dance bars is liable to be struck down on the ground of violating the fundamental right of owners and employees “to practice any profession or to carry on any occupation, trade or business“, an issue that was very much reflected in the SC verdict.

This fundamental right enshrined in Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution is, not surprisingly , central to the petition filed by the Bombay Mutton Dealers Association challenging the Maharashtra government's decision to prohibit not just the slaughter of goats but also the sale of mutton for some days in deference to the Jain festival of fasting, Paryushan.

Further, the meat ban decision, like the one related to the dance bars, involves a glaring issue of discrimination too. For, the ban does not extend to the sale of fish.And, as has been widely reported, all that the government counsel could say in the Bombay HC in defence of the discrimination was that there was no slaughter in the case of fish as they would automatically die once they were taken out of water. The wishy-washy explanation has exposed the legal vulnerability of the meat ban, which has political and communal overtones.

All the same, the partisans of the Mumbai meat ban may fancy their chances because of a 2008 SC verdict upholding a similar restriction in Ahmedabad. Even there, the meat ban was in deference to the same Jain festival and the challenge came from the local lobby of butchers. To validate the meat ban in Ahmedabad, the SC had to overrule the Gujarat HC.

Such illiberal rulings from the SC are found on other kinds of bans too. Take its 2005 judgment reversing its own position on the vexed issue of cow slaughter. Way back in 1958, the SC had held that the ban on cow slaughter envisaged by Article 48 did not extend to the cattle that was “not capable of milch or draught“. As a result of the 1958 verdict, various states had allowed the slaughter of cattle that could be classified as “useless“. But all this changed in 2005 when the same SC ruled that the Article 48 ban extended to all the cattle, irrespective of their age and the strain they put on the availability of fodder.

Another blow struck by the SC to liberty was in 2013 when it reinstated the ban on homosexuality . This was a reversal of the historic judgment passed by the Delhi high court in 2009 reading down Section 377 IPC to exempt consensual sex between adults of the same gender from any criminal liability. The Supreme Court verdict of 2013 put the clock back as it re-criminalized all homosexual acts, in effect privileging public morality over constitutional morality .

Similarly , the SC took a retrograde view on laws banning religious conversions.In keeping with the right to propagate religion guaranteed by Article 25, the laws passed by some of the states forbade only those conversions that were based on coercion or fraud. Contrary to the debates held in the Constituent Assembly , the SC held in 1977 that the right to propagate religion did not confer a right on anybody to convert others. While allowing efforts to spread the tenets of a religion, the apex court ruled that anybody engaged in conversion was automatically liable to be punished, even if it was not based on any extraneous considerations.

Insulting comments: SC upholds ban on book against Islam

From the archives of The Times of India 2010

The SC said it was more concerned with peace in society than a person’s fundamental right to freedom of speech and upheld a Maharashtra government ban on a book titled “A Concept of Political World Invasion by Muslims”.

Petitioner R V Bhasin had challenged Maharashtra’s decision four years after the publication of the book to ban it on the ground that it perpetrated hatred. The Bombay HC had said that government committed no wrong by banning the book. “The way this sensitive topic is handled by the author, it is likely to arouse the emotions and sensibilities of even strong minded people... criticism of Islam is permissible like criticism of any religion and the book cannot be banned on that ground...But the author has gone on to pass insulting comments.”

SC: No poetic licence to make Bapu swear

The Times of India, May 15 2015

Dhananjay Mahapatra

The Supreme Court ruled against poetic licence stretching the right to freedom of expression to cast revered figures like Mahatma Gandhi as a character in a fictional work and attributing obscene words to him.

A bench of Justices Dipak Misra and P C Pant upheld the prosecution launched against Devidas Ramachandra Tuljapurkar, editor of magazine `Bulletin' meant for private circulation among members of the All India Bank Association Union, for the poem `Gandhi Mala Bhetala' (I met Gandhi). The poem, written by Vasant Dattatreya Gurjar, was published in the July-August 1994 issue of the magazine. However, it discharged the printer and publisher as they had tendered apologies.

The judgment, authored by Justice Misra, dealt exhaustively with the issue of obscenity , referred to works of famous authors and poets across the world, extracted passages from 40-odd books on Gandhi written by Indians and foreigners and tested poetic licence on the touchstone of `contemporary community standards'.

The question before the court was “whether in a write-up or a poem, keeping in view the concept and conception of poetic licence and the liberty of perception and expression, using the name of a historically respected personality by way of allusion or symbol is permissible“? Using his educational background in literature, Justice Misra dug deep into the works of famous authors to convey what poetic licence was intended to serve and whether using historically revered figures as characters in a poem and attributing obscene words to them served that purpose. Tuljapurkar had claimed that he used the obscene words, as if spoken by Gandhi, to convey the angst in society. He faces prosecution under Section 292 of IPC, which is punishable by upto five years in jail.

The bench accepted sub missions of amicus curiae Fali S Nariman, who said, “Words that had been used in various stanzas of the poem, if spoken in the voice of an ordinary man or by any other person, it may not come under the ambit and sweep of Section 292, but the moment there is established identity pertaining to Mahatma Gandhi, the character of the words change and they assume the position of obscenity .“

The SC said, “Freedom of speech and expression has to be given a broad canvas, but it has to have inherent limitations which are permissible within the constitutional parameters.“ An author's fallacy in imagination could not be attributed to historically revered figures to diminish their value in the minds of people, the bench said. If an author used obscene words and attributed it to such personalities, then he travelled into the field of perversity , it added.

Obscene act in pvt place no offence: Bombay HC

The Times of India, Mar 20, 2016

Rosy Sequeira

Any obscene act in a private place causing no annoyance to others does not constitute offence, ruled the Bombay high court while recently quashing a complaint against 13 men who were arrested from a private party in a flat at Andheri (west).

A bench of Justice Naresh Patil and Justice A M Badar heard their plea to quash the FIR registered by Amboli police station under Indian Penal Code sections 294 (obscene acts and songs) and 34 (acts done by several persons in furtherance of common intention) On December 12 2015, a journalist complained to the local ACP that a private party was going on in a flat where scantily-dressed women were dancing and making obscene gestures at customers and that the latter were showering money on them. A team from Amboli and Oshiwara police stations raided the place. Six women and the flat's owner were asked to visit the police station the next day while the rest were marched to the police station. The FIR was registered against the petitioners as well as others. The petitioners' advocate Rajendra Shirodkar argued that the flat was not a public place where anyone could have accessed it, so it cannot attract the obscenity charge. The judges were told that except obscenity, no other offence was committed by the petitioners. In its March 10 order, the bench said section 294 is meant for punishing persons indulging in an obscene act in any public place causing annoyance to others. The judges said it must be shown that public has a right to have free ingress to such a place. "Viewed from this angle, the flat/apartment in a building owned by some private person meant for private use of such owner cannot be said to be a public place," they added. The judges said the FIR, even prima facie, does not disclose any offence. They concluded that obscene act alleged in the FIR was not being conducted at a public place and that too to the annoyance of others.

Restricting Internet, cellphones

Gujarat HC upholds mobile internet curfew during Patel stir

The Times of India, Sep 19 2015

Says the ban was `just and proper'

The Gujarat high court has upheld the state government's decision to impose a week-long mobile internet ban in August 2015 when riots broke out on August 25 following the arrest of Hardik Patel, the torchbearer of the ongoing Patidar reservation stir. Terming the ban “just and proper“, the court turned down a PIL filed by law student Gaurav Vyas, who had challenged the blocking of mobile internet services on the ground that it violated fundamental rights. Vyas had also questioned the city police commissioner's invocation of CrPC's Section 144 (power to issue orders in urgent cases of nuisance or apprehended danger) to restrict mobile internet services.

The petitioner contended that the government should have blocked certain websites or services by applying Information Technology Act's Section 69A (blocking content in case security of state is threatened). “Applying Section 144 of CrPC to block internet is arbitrary and beyond the scope of the provisions of the law,“ he argued in his plea.

In response, the government submitted that there was sufficient and valid ground to exercise CrPC's Section 144 to block mobile internet services, as “it would have been difficult to restore peace otherwise“. The state government also submitted that the exercise of power was not extreme since internet was still accessible on broadband and Wi-Fi services.

After hearing the case, the court said Section 144 of the CrPC was exercised for preventive action. In a given case, Section 69A of the IT Act might be exercised for blocking certain websites, whereas directions could be issued under CrPC provisions to service providers to block internet facilities. The petitioner's advocate said they planned to move the SC against the HC order.

Social media

SC:Can't ban social media over sleaze

Sources: The Times of India

1. The Times of India, Dec 05 2015, AmitAnand Choudhary

Can't ban social media over offensive content: SC to NGO

Dec 05 2015 : The Times of India (Delhi) SC: Can't ban social media over sleaze Turning down an NGO's plea to ban social networking sites like Facebook and WhatsApp for use of their platforms to circulate offensive and vulgar material, the Supreme Court on Friday asked the government to examine if the sites could be prosecuted, reports Amit Anand Choudhary. The SC told the NGO, “You are now asking blocking of sites. You may later ask for banning mobile phones.It's not a solution and it cannot be done,“ the SC said.

The Centre earlier told the court it was tough to identify people who upload and share sex videos and also expressed its inability to keep a check on such material.

But Apex Court Asks Centre Whether Sites Can Be Prosecuted

The Supreme Court asked the Centre to examine if social networking sites like Facebook and WhatsApp can be prosecuted for use of their platforms to circulate offensive and vulgar material but turned down a plea to block the sites. A social justice bench of justices Madan B Lokur and U U Lalit asked the Centre to look into the issue after two cases were brought to its notice in which people were booked for circulating rape videos through WhatsApp in Mumbai and running a sex racket for paedophiles through a Facebook account but no action was taken against the social networking sites. The Centre had earlier told the court that it was difficult to identify people who upload ed sex videos through mobile phones and shared through WhatsApp. It said culprits could be easily caught if such activities were done through a computer but it was difficult to find the source when the crime was commit ted through phones.

With the government ex pressing its inability to keep a check on material shared through WhatsApp, a Hyderabad-based NGO, Prajwala, told the bench that action should also be taken against the networking sites and they should be blocked. Head of the NGO, Sunitha Krishnan, asked the court to direct the government to put in place a mechanism to regulate sites and keep a check on the content being circulated through WhatsApp.

The bench, however, said blocking is not a feasible solution and turned down the plea.“You are now asking for blocking of sites. You may later ask for banning mobile phones. It is not a solution and it cannot be done,“ the bench said.

“Let the government first respond to the issue and then we will consider,“ the bench said asking additional solicitor general Maninder Singh to look into why networking sites were not booked by Kerala and Maharashtra police.

Taking suo motu cognizance on Prajwala's letter written to the Chief Justice of India pointing out nine rape videos being circulated through WhatsApp, the bench had directed a CBI probe into all those cases.

2015

Curbs on hate speech on Facebook

The Times of India, Nov 13 2015

Pankaj Doval

India tops in curbs on FB content in 2015

15,155 pleas granted: 3 fold rise from 2014

The Indian government sought the maximum number of content restrictions from various platforms of social networking behemoth Facebook in the first six months of this year than any other country globally. The world's biggest social networking platform said it granted requests from authorities in India for some 15,155 pieces of content to be blocked on its platform, its WhatsApp and Messenger apps and its photo-sharing app, Instagram. This was revealed by Facebook in its latest report on government data requests for the period between January and June 2015. The Indian government's requests more than tripled rom the 4,960 items where it sought restrictions during he same period in 2014 Facebook said. India accounted for some nearly 74% of the more than 20,000 pieces of content re stricted worldwide at the beh est of 92 countries. Facebook said that the re quests to block the material n India were made “under lo cal laws prohibiting criti cism of a religion or the state.“ “Facebook does not provide any government with `back doors' or direct ac cess to people's data,“ the US headquartered company . Meanwhile, Facebook said the US topped the list of nations requesting user data.It logged 17,577 requests in the first half of 2015, up from 15,433 a year earlier. India was second with 5,115, up from 4,559 last year. India is home to the second largest user base of Facebook with over 125 million users. “We restricted access in India to content reported primarily by law enforcement agencies and the India computer emergency response team within the ministry of communications and information technology because it was anti-religious and hate speech that could cause unrest and disharmony within India,“ it added.

Bans in 2015

India Today, August 6, 2015

Damayanti Datta

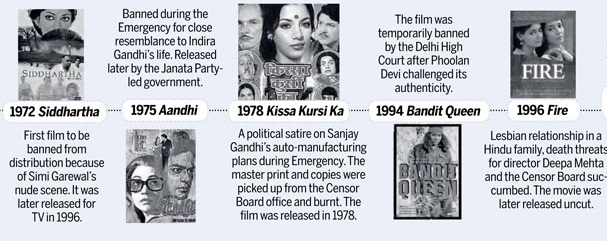

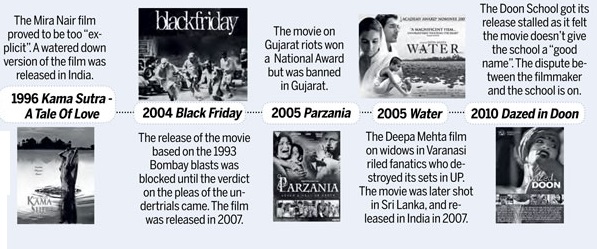

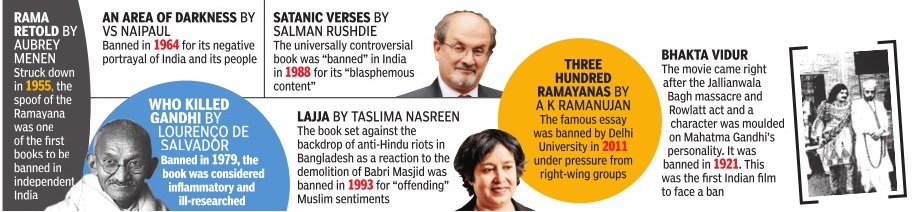

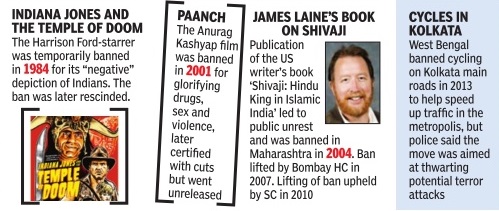

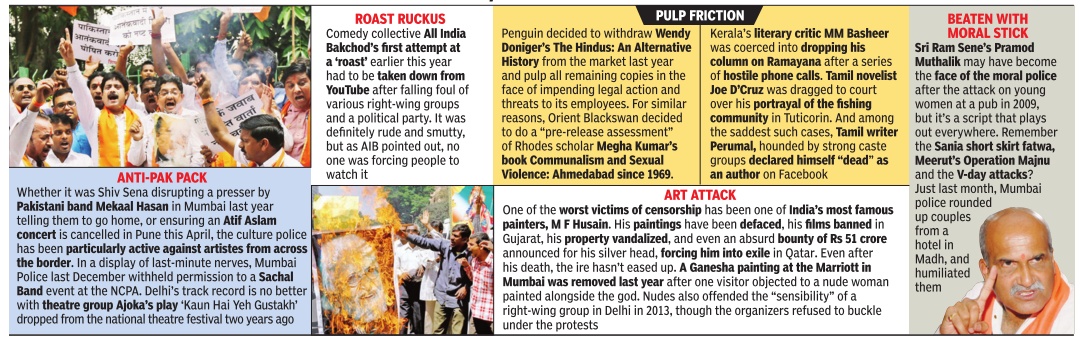

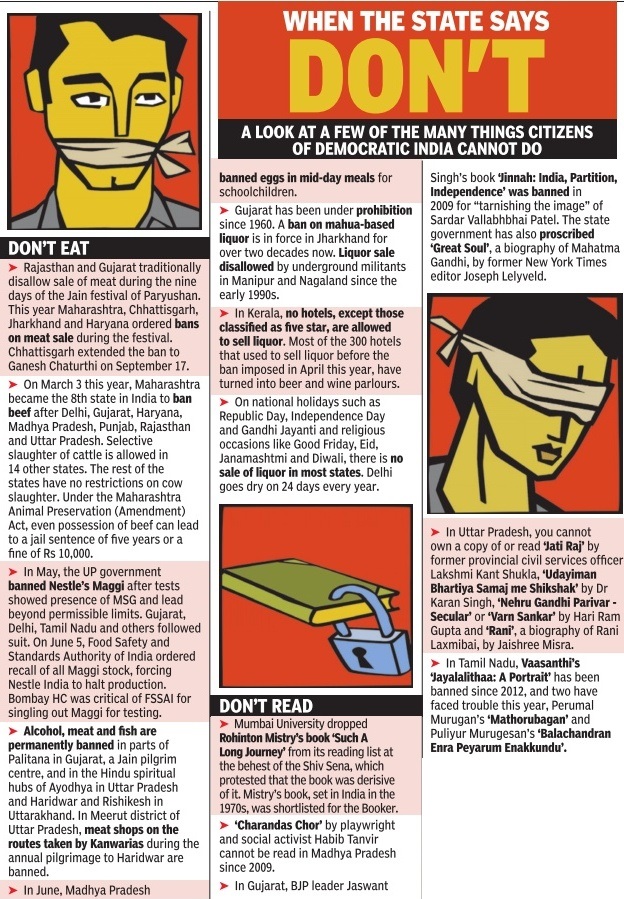

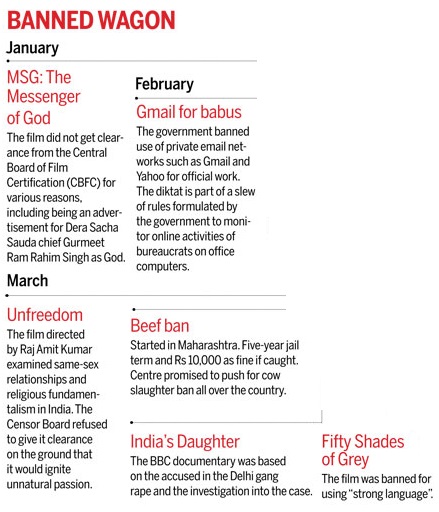

Religion, politics and sex. Caught between the trinity, Independent India has managed to silence several voices and opinions. While the recent uproar over the ban on porn sites forced the government to retract, check out the milestones of our long heritage of intolerance.

Religion, politics and sex. Caught between the trinity, Independent India has managed to silence several voices and opinions. While the recent uproar over the ban on porn sites forced the government to retract, check out the milestones of our long heritage of intolerance.

5 times the Supreme Court restored our faith in justice in July 2015

July 30

MIDNIGHT HEARING

For the first time, the Supreme Court was opened at 2 a.m. for a three-judge bench headed by Justice Dipak Misra to hear the final plea of 1993 Bombay blasts convict Yakub Memon, a few hours before his execution.

July 30

TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY

A bench of Justices Anil R. Dave and Kurian Joseph allowed a minor rape victim to terminate pregnancy after 24 weeks, making an exception to the rule which allows abortion until the 20th week of pregnancy.

July 8

BAN ON PORNOGRAPHY

The Supreme Court said India can't ban porn. Chief Justice of India H.L. Dattu said a total ban on sex sites would violate privacy and personal liberty.

July 6

RIGHTS OF UNWED MOTHERS

An unwed mother can be the sole guardian of a child without prior consent of the biological father, ruled Justice Vikramajit Sen.

July 1

MEDICAL NEGLIGENCE

Justices J.S. Khehar and S.A. Bobde ordered Tamil Nadu government to pay Rs 1.8 crore, one of the largest compensations in a medical negligence case, to an 18-year-old girl who lost her vision at birth in a government-run hospital. 10 films that faced the ire of government, censor board and a prudish society.

Parties fail to honour tolerance

The Times of India Jan 04 2016

Dhananjay Mahapatra

Tolerance had been the most used word in poli tics and social media for a good part of last year. In a fashionable and contemporary evolution of the term `tolerance', litterateurs returned awards given to them. Bollywood icons expressed their fear against growing intolerance. Political parties stalled Parliament to register their protest against intolerance.

Today social networking sites -Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp -are the key reflectors of public opinion.The young and not so young possess smartphones that update them about every single event. And in a matter of seconds, they register their reaction and opinions. Their opinion matters.

Public opinion mattered a lot with rulers from time immemorial. Even the Ramayana describes how Lord Rama was forced to abandon his wife Sita after rescuing her from the clutches of Ravana merely on the basis of public perception despite knowing that there was no truth behind the public opinion.

In the Jataka stories, we had read how a Brahmin was duped of a goat by three thieves. When the Brahmin was on his way back home with the goat, the three separately went to him and each of them insisted that it did not behove a Brahmin to carry a dog.The Brahmin shooed away the first thief with abuses. When the second one reiterated the same thing, a doubt crept into the Brahmin's mind. And a little later, when the third one too insisted with vehemence that it was a dog, the Brahmin believed it and ran away abandoning the goat. The gang of three had a nice feast, says the Jatakastory .

That is the power of public opinion and politicians have understood it. In the recent past, political parties had hired IT professionals to create trends in social network ng sites with catchy presentation of incidents and views of their leaders to garner maximum hits. AamAadmi Party has left everyone behind on this count.

The power of public opin on stems from the fact that our Constitution provides citizens with right to freedom of speech, a guarantee that had been broadened by the Supreme Court through its numerous judgments over the years. During the time when here was not much debate on tolerance and social networking sites were absent, he SC in S Rangarajan vs P Jagjivan Ram [1989 (2) SCC 574] had given a far-sighted ruling which even today could be referred to aptly in view of the tolerance debate.

It had said: `The different views are allowed to be expressed by proponents and opponents not because they are correct, or valid but because there is freedom in this country for expressing even differing views on any issue...Freedom of expression which is legitimate and constitutionally protected, cannot be held to ransom by an intolerant group of people.“

“The fundamental freedom under Article 19(1)(a) can be reasonably restricted only for the purposes mentioned in Article 19(2) and the restriction must be justified on the anvil of necessity and not the quicksand of convenience or expediency . Open criticism of government policies and operations is not a ground for restricting expression.

“We must practice tolerance of the views of others.Intolerance is as much dangerous to democracy as to the person himself.“

It was re-emphasised by the SC in S Khushboo vs Kanniamal [2010 (5) SCC 600].It had said that right to freedom of speech and expression, though not absolute, was necessary as we need to tolerate unpopular views.This right requires free flow of opinions and ideas essential to sustain the collective life of the citizenry . While an informed citizenry is a precondition for meaningful governance, the culture of open dialogue is generally of great societal importance.

So far so good. But, there is a flip side to this tolerance debate. If a person belonging to a majority community rejected an invitation for a religious function conducted by a per son from minority community, he would be branded intolerant. But, if we just reverse the characters, then the action of the person from minority community would be treated as legitimate since he had the right to freedom of religion.

If a person from majority community prefers to study Sanskrit or any ancient Hindu subject, he would be branded obscurantist and even fundamental. But, if he decides to study German, French, Japanese or any other foreign language, then he would be bracketed with those having progressive outlook. That is the reason probably why we have eminent Indologists from foreign countries.

Tolerance is a double edged sword. When Kirt Azad was suspended for al leged anti-party activities by BJP, there was a chorus by Congress and AAP terming the action undemocratic, tha it smacked of intolerance.

But, in November, AAP had suspended its own MLA Pankaj Pushkar from the as sembly for raising an issue that did not grab eyeballs on social networking sites -economically weaker category in schools.

Last month, Congress sacked the editor of its mouthpiece for publishing articles that intended to praise its president Sonia Gandhi but contained a line that her father had links with fascists in Italy. It is easy to ad vocate tolerance and free speech, but rules take a somersault when it comes to self.

Eight major threats to freedom of expression

Eight reasons why India cannot speak freely, TNN | Sep 11, 2016

By Ramchandra Guha

In a new book, Ramachandra Guha finds out what's eating away at the moral and institutional foundations of Indian democracy

Some years ago, I characterized our country as a '50-50 democracy'. India is largely democratic in some respects such as free and fair elections… but only partly democratic in other respects. One area in which the democratic deficit is substantial relates to freedom of expression.

Let me analyse what I regard as the eight major threats to freedom of expression in contemporary India. The first threat is the retention of archaic colonial laws. There are several sections in the Indian Penal Code (IPC) that are widely used (and abused) to ban works of art, films, and books... These sections — of which the most dangerous is Section 124A, the so-called sedition clause — give the courts and the state itself an extraordinarily wide latitude in placing limits to the freedom of expression.

The second threat is constituted by imperfections in our judicial system. Our lower courts in particular are too quick and too eager to entertain petitions seeking bans on individual films, books or works of art... The life of a book or a work of art or a film has become increasingly captive to the ease with which a community, any community at all, can complain that its sentiments, any sentiments, are hurt or offended by it...

A third threat is the rise and rise and further rise of identity politics. In India today, we imagine our heroes to be absolutely perfect. I wonder if this was always so. Yudhishthira and Rama were capable of deceit and deviant behaviour — and our ancestors were not surprised or angered to know this. But now Bengalis shall be enraged at even the mildest criticism of Subhas Chandra Bose, Tamils at the mildest criticism of Periyar, Maharashtrians at the mildest criticism of Shiva ji, Dalits at the mildest criticism of Ambedkar, Hindutvawadis at the mildest criticism of Savarkar, and so on.

Indians are increasingly touchy, thin-skinned, intolerant, and, I must add, humourless. The rise of humourlessness is the other side of the rise of identity politics. And without humour, there cannot be great literature.

The fourth threat to freedom of expression in India is the behaviour of the police force. Even when courts take the side of writers and artists, the police generally side with the goondas who harass them.

The fifth threat is the pusillanimity or, more often, the mendacity of politicians. Indeed, no major or minor Indian politician, as well as no major or minor Indian political party, has ever supported writers, artists or film-makers against thugs and bigots. Rajiv Gandhi's Congress government banned Salman Rushdie's novel The Satanic Verses even before Ayatollah Khomeini issued his fatwa against it. In West Bengal, the (well-educated and professedly literature-loving) communist chief ministers Jyoti Basu and Buddhadeb Bhattacharya had Taslima Nasrin's novels banned, and even had the author externed from the state. The record of the BJP is no better. The vandalism of the Husain-Doshi Gufa happened when Narendra Modi was chief minister of Gujarat.

While he was in that post, Hindutva activists effectively destroyed the country's best art department, at the Maharaja Sayajirao University in Baroda. Moving on to the leaders of regional parties, neither Jayalalithaa nor M. Karunanidhi did anything to protect the novelist Perumal Murugan when he was coerced by a group of caste vigilantes in Tamil Nadu to stop writing altogether. In acting (or nor acting) as they do, these politicians are motivated largely by electoral considerations. They do not wish to offend, or to be seen to be offending, a particular caste, sect or religious group, lest they vote against them in the next election.

A sixth threat to freedom of expression is constituted by the dependence of the media on government advertisements. This is especially acute in the regional and sub-regional press...The state and political parties can, and do, coerce, suppress or put barriers in the way of independent reporters and reportage. So can the private sector, using material rather than punitive force. Thus, a seventh threat to freedom of expression is constituted by the dependence of the media on commercial advertisements. This is especially pertinent in the case of English-language newspapers and television channels that cater to the affluent middle class. Companies that make products that have damaging side effects are rarely criticized for fear that they will stop providing ads...

I come now to my eighth and final threat to freedom of expression. This is constituted by careerist or ideologically driven writers. To be sure, most writers and artists have strong opinions on politics and society. That is why we write, that is why we paint, that is why we make films, that is why we write plays. But no creative person should be so foolish or mistaken as to mortgage his or her independence, his or her conscience, to a political party.

Edited excerpts from Democrats and Dissenters, Allen Lane (Penguin Random House)