Forests: India

Contents |

The forests of India, as in 1911

This article was written around 1911 when conditions were Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles |

Extracted from:

Encyclopaedia of India

1911.

No further details are available about this book, except that it was sponsored in some way by the (British-run) Government of India.

NOTE: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to the correct place.

Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book.

Forests

The forests of India, both as a source of natural wealth and as a department of the administration, are beginning to receive their proper share of attention. Up to the middle of the 19th century the destruction of forests by timber-cutters, by charcoal-burners, and above all by shifting cultivation, was allowed to go on everywhere unchecked. The extension of cultivation was considered as the chief care of government, and no regard was paid to the improvident waste going on on all sides. But as the pressure of population on the soil became more dense, and the construction of railways increased the demand for fuel, the question of forest conservation forced itself into notice. It was recognized that the inheritance of future generations was being recklessly sacrificed to satisfy the immoderate desire for profit. And at the same time the importance of forests as affecting the general meteorology of a country was being learned from bitter experience in Europe. On many grounds, therefore, it became necessary to preserve what remained of the forests in India, and to repair the mischief of previous neglect even at considerable expense. In 1844 and 1847 the subject was actively taken up by the governments of Bombay and Madras. In 1864 Dr Brandis was appointed inspector-general of forests to the government of India, and in the following year an act of the legislature was passed (No. VII. of 1865).

The regular training of candidates for the Forest Department in the schools of France and Germany dates from 1867. In the interval that has since elapsed, sound principles of forest administration have been gradually extended. Indiscriminate timber-cutting has been prohibited, the burning of the jungle by the hill tribes has been confined within bounds, large areas have been surveyed and demarcated, plantations have been laid out, and, generally, forest conservation has become a reality. Systematic conservancy of the Indian forests received a great impetus from the passing of the Forest Law in 1878, which gave to the government powers of dealing with private rights in the forests of which the chief proprietary right is vested in the state. The Famine Commission of 1878 urged the importance of forest conservancy as a safeguard to agriculture, pointing out that a supply of wood for fuel was necessary if cattle manure was to be used to any extent for the fields, and also that forest growth served to retain the moisture in the subsoil. They also advised the protection and extension of communal rights of pasture, and the planting of the higher slopes with forest, with a view to the possible increase of the water-supply.

These recommendations embody the principle upon which the management of the state forests is based. In 1894 the government divided forests into four classes: forests the preservation of which is essential on climatic or physical grounds, forests which supply valuable timber for commercial purposes, minor forests, and pasture lands. In the first class the special purpose of the forests, such as the protection of the plains from devastation by torrents, must come before any smaller interests. The second class includes tracts of teak, sal or deodar timber and the like, where private or village rights of user are few. In these forests every reasonable facility is afforded to the people concerned for the full and easy satisfaction of their needs, which are generally for small timber for building or fuel, fodder and grazing for their cattle, and edible products for themselves; and considerations of forest income are subordinated to those purposes.

Restrictions necessary for the proper conservancy of the forests are, however, imposed, and the system of shifting cultivation, which denudes a large area of forest growth in order to place a small area under crops, is held to cost more to the community than it is worth, and is only permitted, under due regulation, where forest tribes depend on it for their sustenance. In the third place, there are minor forests, which produce inferior or smaller timber. These are managed mainly in the interests of the surrounding population, and supply grazing or fuel to them at moderate rates, higher charges being levied on consumers who are not inhabitants of the locality. The fourth class includes pastures and grazing grounds. In these even more than in the third class the interests of the local community stand first. The state forests, which are under the control of the forest department, amounted in1901-1902to about 217,500 sq. m., or more than one-fifth of the total area of British India, varying from 61% in Burma to 4% in the United Provinces.

Timbers

A large part of the reserved forests, where the control of the forest department is most complete, consists of valuable timber, in which the first place is held by teak, found at its best in Burma, especially in the upper division, and on the south-west coast of India, in Kanara and Malabar. It is also the most prevalent and valuable product of the forests at the foot of the Ghats in Bombay, and along the Satpura and Vindhya ranges, as far as the middle of the Central Provinces. Here it meets the sal, which however is more especially found in the sub-Himalayan tracts of the United Provinces and Eastern Bengal and Assam. In the Himalayas themselves the deodar and other conifers form the bulk of the timber, while in the lower ranges, such as the Khasi hills in Assam, and those of Burma, various pines are prominent. In the north-east of Assam and in the north of Upper Burma the Ficus elastica, a species of india-rubber tree, is found.

The sandal-wood flourishes all along the southern portion of the Ghats, especially about Mysore and Coorg; and in the same regions, as well as in Upper India, the blackwood occurs. A valuable tree, known as the padouk, is at present restricted almost entirely to the Andaman Islands, with a scattering in Lower Burma. There are many other timber trees that are in general demand in different parts of India, but the above are the best known outside that country. There is also the universal bamboo, and in the north-western tracts the equally useful rattan. The annual timber yield of the Indian forests is about fifty millions of cubic feet, excluding what is used for local purposes. About half of this quantity comes from the forests of Burma, where large amounts of teak and other woods are annually extracted, chiefly through the agency of private firms. It is, however, only the more valuable of the woods, such as teak, sandal-wood, ebony and the like, which find a market abroad. The total value of the export trade in forest produce averages between 1 a and 2 millions annually.

Community governance

The Times of India, December 13, 2016

'Just 3% forest area under community governance'

Jayashree Nandi

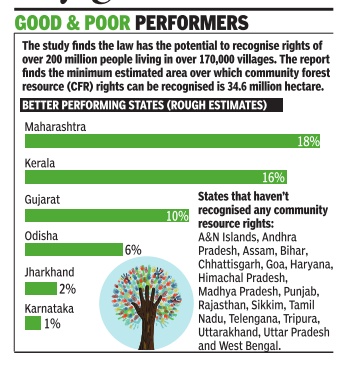

Millions of forest dwellers in the country still do not have rights to conserve forests or access to forest resources. Ten years after the Forest Rights Act was passed by Parliament -a law that secures rights of forest dwellers and empowers them to protect forests -only about 3% of the potential forest area for community governance has been recognised, says a new study .

The `Promise and Performance: Ten Years of the Forest Rights Act' finds that the rights to manage, conserve and use forest resources by forest-dwelling tribes could have been recognised over an area of 34.6 million ha -an area larger than Madhya Pradesh -but has only been recognised in little over 1.1 million ha or only 3% of the potential.

The report by Community Forest Rights-Learning and Advocacy (CFR-LA) uses data from Census 2011 to assess total forest area inside and outside village boundaries (34.6 million ha) as the minimum potential area over which community forest resource rights could be recognised. This includes the minimum estimated forest area outside revenue village boundaries under custom ary use. The authors rely on data from the ministry of tribal affairs and state governments to compute the actual area over which rights have been recognised and it is estimated that the law can deliver community forest resource rights to about 200 million tribals and other forest dwellers living in 170,000 villages across the country.

The reason for such poor performance of the act, authors say is a “lack of political will“ and opposition by “forest bureaucracy“ or the ministry of environment and forests in handing over governance rights to the communities.

But why is this law important? Because it transfers decision making powers and forest conservation responsibilities to gram sabhas.The Niyamgiri case in Odisha has already established how gram sabhas can play a powerful role in protecting cultural and resource rights of indigenous communities after gram sabhas unanimously voted against bauxite mining in hills inhabited by the Dongria Kondhs.

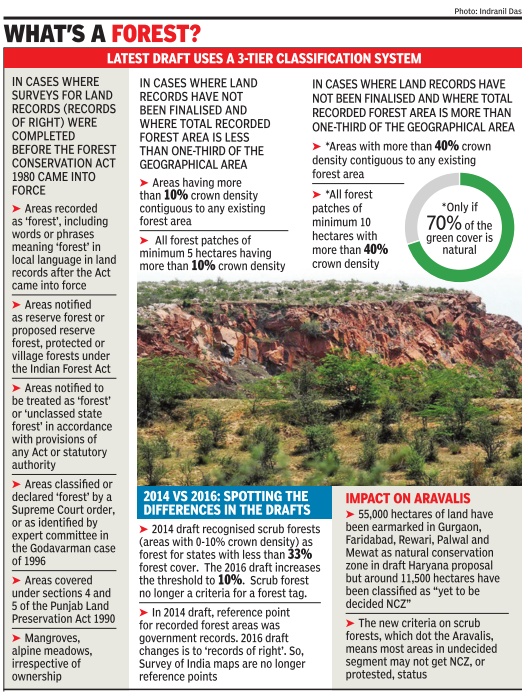

Definition of a forest in India

See graphic, ' The definition of a forest in India '

Diversion of forest land for non-forest purposes

2014: 36k ha for infra projects

The Times of India, Apr 29 2015

36k ha of forest land diverted for infra projects in 2014

The Centre had given its approval for diversion of 35,867 hectares of forest land in a total of 783 cases, involving roads, railway lines and other infrastructure projects in 2014 Sharing the forest diversion figures, the Centre informed Parliament that the maximum forest land of 9,830 ha was diverted in Madhya Pradesh, followed by Odisha (4,516 ha), Andhra Pradesh (3,334 ha), Chhattisgarh (3,236 ha), Jharkhand (2,989 ha) and Maharashtra (2,380 ha).

However, there was no diversion of forest land in Jammu & Kashmir, Kerala, Megh alaya, Nagaland, Tamil Na du, Telangana, Pondicherry Daman and Diu and Lakshad weep last year.

Responding to a different query on whether the tribal af airs ministry had raised ob ections to the dilution of forest aw, Union environment min ster Prakash Javadekar, in his written response, said, “The process of inter-ministeria consultation is still going on.“

He said the environment ministry has formulated revised draft guidelines on ensuring compliance with the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, in cases of diversion of forest land for nonforest purpose under the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980.

Guidelines for diverting forest land

The economic viability of any development project that involves diversion of forest land may now reduce with the environment ministry coming up with new costbenefit analysis guidelines.

The new guidelines submitted to the National Green Tribunal (NGT) by the ministry comprise a number of new costs for diversion of forest land including possession costs and habitat fragmentation costs.

The enhanced cost of diverting forest land will come into effect only when the process of arriving at the net present value (NPV) of forests, as prescribed by the Supreme Court in 2008, is re vised. The new guidelines, however, may highlight the steep environmental costs of diverting forests, say officials and help the ministry make a judicious decision.

According to the new guidelines, the ecosystem service cost of diversion will be assessed based on the NPV formula. While 30% of the NPV will be added to the diversion cost as the cost of “possession of forest land“, an additional 50% of NPV cost will be added as “habitat fragmentation cost“. Guidelines say 10% of NPV cost will be added for loss of animal husbandry productivity and soil moisture conservation costs.

The environment ministry till now was doing the cost-benefit analysis based on guidelines drafted in 2004, which, experts say , are outdated. The ministry came up with new guidelines in compliance with the National Green Tribunal (NGT's) order a few years ago in Uttarakhand activist Vimal Bhai's petition against displace ment of forest dwellers due to a hydroelectric project.

“The new cost-benefit guidelines account for various ecological services like water recharge, nutrients in the soil, carbon sequestration and others. They also account for the cost of possession of forest land by the project proponent. Now the viability of certain projects on forest land will reduce,“ said an environment ministry official, requesting anonymity .

The government, however, has not revised the NPV (amount to be paid by project proponents) despite court orders. They were to revise it every three years.

Vimal Bhai, the petitioner, however, said he was apprehensive if the new guidelines will actually be imp lemented. “The government agencies have a very poor record of implementing guidelines,“ he said.

Referring to a clause in the new guidelines which says the forest dwellers will be paid 1.5 times of what they would have earned in two years towards social cost of rehabilitation, Vimal said, “Their income cannot be quantified because their life is completely dependent on the forest.“

Madhu Verma of the Indian Institute of Forest Management in Bhopal said “implementation or assessing the viability of a project is up to the ministry . But the new guidelines do account for possession of forest land.The social costs of forest diversion are enormous and difficult to quantify .“

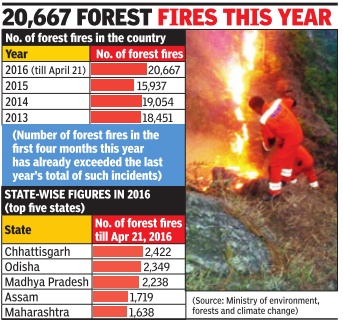

Forest fires

Number of forest fires: 2013-16

See graphic, ' Number of forest fires in the country, 2013-April 2016, year-wise… '

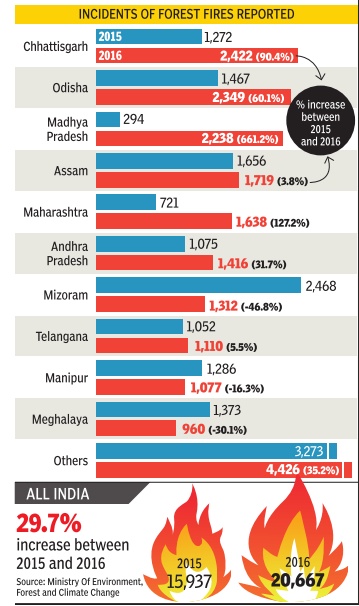

Number of forest fires: 2015-16

See graphic, ' Incidents of forest wires reported, 2015-16, state-wise<>/ '

Hinduism, Buddhism and forests

The Times of India, June 9, 2016

Devdutt Pattanaik

In the Sama Veda, the hymns of the Rig Veda are turned into melodies.

These melodies are classified into two groups: the forest songs aranya-gaye-gana or Forest Songs, and grama-gaye-gana or Settlement Songs.This divide plays a key role in the understanding of dharma.

Forest is the default state of nature.In the forest, there are rules. The fit survive and the unfit die. The stronger, or the smarter, have access to food. The rest starve. There is no law, no authority and no regulation. This is called `matsya nyaya' or law of the fishes, the vedic equivalent of the law of the jungle. This is prakriti, visualised as Kali, the wild goddess who runs naked with unbound hair, of the puranas.

Humans domesticate the forest to turn the forest into fields and villages for human settlement. Here, everything is tamed: plants, animals, even humans, bound by niti, rules; riti, tradition; codes of conduct, duties and rights.Here, there is an attempt to take care of the weak and unfit. This is the hallmark of sanskriti or civilisation, visualised as Gauri, the docile goddess who is draped in a green sari, and whose hair is tied with flowers, who takes care of the household.

The Ramayana tells the story of Rama who moves from Ayodhya, the settlement of humans, the realm of Gauri, into the forest, the realm of Kali. The Mahabharata tells the story of the Pandavas who are born in the forest, then come to Hastinapur, and then return to the forest as refugees, and then once again return to build Indraprastha, then yet again return to the forest as exiles, and finally , after the victory at war, and a successful reign, they return to the forest following retirement.

As children, we are trained to live in society that is brahmacharya. Then we contribute to society as householders grihastha. Later we are expected to leave for the forest vanaprastha, and then comes the hermit life or sanyasa, when we seek the world beyond the forest.

According to the Buddhist Sarvastivadin commentary , Abhidharma mahavibhasa-sastra, forest or vana, is one of the many etymologies of the word `nirvana', the end of identity , prescribed by Buddhist scriptures, which is the goal of dhamma, the Buddhist way .

Rama lives in a city, and so does Ravana. But Rama follows rules. Ravana does not care for rules. In other words, Ravana follows matsya nyaya though he is a city-dweller, a nagara-vasi. That is adharma. If Ravana uses force to get his way, Duryodhana uses his cunning, also focussing on the self rather than the other. This is adharma.Dharma is when we function for the benefit of others. It has nothing to do with rules. Which is why Krishna, the rule-breaker, is also upholding dharma, for he cares for the other.

In the forest, everyone is driven by self-preservation. Only humans have the wherewithal to enable and empower others to survive, and thrive. To do so is dharma. It has nothing to do with rules or tradition. It is about being sensitive to, and caring for, the other. We can do this whether we are in the forest, or in the city. And so it is in the vana or forest, that Krishna dances with the gopikas, making them feel safe even though they are out of their comfort zone.

Without appreciating the forest and the field, Kali and Gauri the animal instinct and human capability any discussion of dharma will be incomplete.