Forests: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The forests of India, as in 1911

This article was written around 1911 when conditions were Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles |

Extracted from:

Encyclopaedia of India

1911.

No further details are available about this book, except that it was sponsored in some way by the (British-run) Government of India.

NOTE: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to the correct place.

Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book.

Forests

The forests of India, both as a source of natural wealth and as a department of the administration, are beginning to receive their proper share of attention. Up to the middle of the 19th century the destruction of forests by timber-cutters, by charcoal-burners, and above all by shifting cultivation, was allowed to go on everywhere unchecked. The extension of cultivation was considered as the chief care of government, and no regard was paid to the improvident waste going on on all sides. But as the pressure of population on the soil became more dense, and the construction of railways increased the demand for fuel, the question of forest conservation forced itself into notice. It was recognized that the inheritance of future generations was being recklessly sacrificed to satisfy the immoderate desire for profit. And at the same time the importance of forests as affecting the general meteorology of a country was being learned from bitter experience in Europe. On many grounds, therefore, it became necessary to preserve what remained of the forests in India, and to repair the mischief of previous neglect even at considerable expense. In 1844 and 1847 the subject was actively taken up by the governments of Bombay and Madras. In 1864 Dr Brandis was appointed inspector-general of forests to the government of India, and in the following year an act of the legislature was passed (No. VII. of 1865).

The regular training of candidates for the Forest Department in the schools of France and Germany dates from 1867. In the interval that has since elapsed, sound principles of forest administration have been gradually extended. Indiscriminate timber-cutting has been prohibited, the burning of the jungle by the hill tribes has been confined within bounds, large areas have been surveyed and demarcated, plantations have been laid out, and, generally, forest conservation has become a reality. Systematic conservancy of the Indian forests received a great impetus from the passing of the Forest Law in 1878, which gave to the government powers of dealing with private rights in the forests of which the chief proprietary right is vested in the state. The Famine Commission of 1878 urged the importance of forest conservancy as a safeguard to agriculture, pointing out that a supply of wood for fuel was necessary if cattle manure was to be used to any extent for the fields, and also that forest growth served to retain the moisture in the subsoil. They also advised the protection and extension of communal rights of pasture, and the planting of the higher slopes with forest, with a view to the possible increase of the water-supply.

These recommendations embody the principle upon which the management of the state forests is based. In 1894 the government divided forests into four classes: forests the preservation of which is essential on climatic or physical grounds, forests which supply valuable timber for commercial purposes, minor forests, and pasture lands. In the first class the special purpose of the forests, such as the protection of the plains from devastation by torrents, must come before any smaller interests. The second class includes tracts of teak, sal or deodar timber and the like, where private or village rights of user are few. In these forests every reasonable facility is afforded to the people concerned for the full and easy satisfaction of their needs, which are generally for small timber for building or fuel, fodder and grazing for their cattle, and edible products for themselves; and considerations of forest income are subordinated to those purposes.

Restrictions necessary for the proper conservancy of the forests are, however, imposed, and the system of shifting cultivation, which denudes a large area of forest growth in order to place a small area under crops, is held to cost more to the community than it is worth, and is only permitted, under due regulation, where forest tribes depend on it for their sustenance. In the third place, there are minor forests, which produce inferior or smaller timber. These are managed mainly in the interests of the surrounding population, and supply grazing or fuel to them at moderate rates, higher charges being levied on consumers who are not inhabitants of the locality. The fourth class includes pastures and grazing grounds. In these even more than in the third class the interests of the local community stand first. The state forests, which are under the control of the forest department, amounted in1901-1902to about 217,500 sq. m., or more than one-fifth of the total area of British India, varying from 61% in Burma to 4% in the United Provinces.

Timbers

A large part of the reserved forests, where the control of the forest department is most complete, consists of valuable timber, in which the first place is held by teak, found at its best in Burma, especially in the upper division, and on the south-west coast of India, in Kanara and Malabar. It is also the most prevalent and valuable product of the forests at the foot of the Ghats in Bombay, and along the Satpura and Vindhya ranges, as far as the middle of the Central Provinces. Here it meets the sal, which however is more especially found in the sub-Himalayan tracts of the United Provinces and Eastern Bengal and Assam. In the Himalayas themselves the deodar and other conifers form the bulk of the timber, while in the lower ranges, such as the Khasi hills in Assam, and those of Burma, various pines are prominent. In the north-east of Assam and in the north of Upper Burma the Ficus elastica, a species of india-rubber tree, is found.

The sandal-wood flourishes all along the southern portion of the Ghats, especially about Mysore and Coorg; and in the same regions, as well as in Upper India, the blackwood occurs. A valuable tree, known as the padouk, is at present restricted almost entirely to the Andaman Islands, with a scattering in Lower Burma. There are many other timber trees that are in general demand in different parts of India, but the above are the best known outside that country. There is also the universal bamboo, and in the north-western tracts the equally useful rattan. The annual timber yield of the Indian forests is about fifty millions of cubic feet, excluding what is used for local purposes. About half of this quantity comes from the forests of Burma, where large amounts of teak and other woods are annually extracted, chiefly through the agency of private firms. It is, however, only the more valuable of the woods, such as teak, sandal-wood, ebony and the like, which find a market abroad. The total value of the export trade in forest produce averages between 1 a and 2 millions annually.

The forest cover of India, as in...

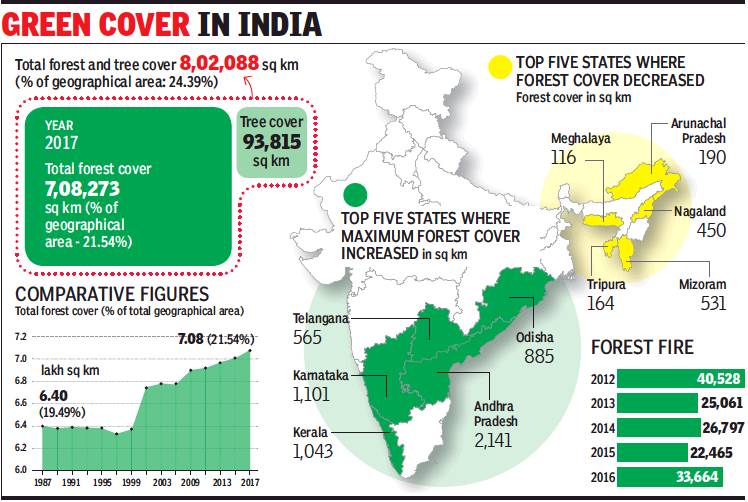

1987- 2017: an increase, but NE a cause for concern

Change in forest and tree cover;

The best and worst five states;

Forest fires, 2012-17

From: Vishwa Mohan, India’s forest cover increases by 1%, but NE a cause for concern, February 13, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

1. Total forest and tree cover, 1987- 2017;

Change in forest and tree cover;

The best and worst five states;

Forest fires, 2012-17

Shrinkage In ‘Moderately Dense’ Areas Worries Experts

India’s forest cover increased by 6,778 sq km over the last two years with Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Odisha and Telangana increasing their green footprint during the period though there is a worrying decline in six northeastern states, including a shrinkage of 630 sq km in the eastern Himalayas.

While overall green cover, including tree patches outside recorded forest areas, reported an incremental 1% increase (8,021 sq km) over the last assessment year in 2015, the quality of forests remain a hotly debated subject even as satellite monitoring has increased availability of data.

The increase, which is based on satellite data and subsequent ‘ground truthing’, has put the total forest cover at 7,08,273 sq km which is 21.54% of the country’s geographical area.

Releasing the India State of Forest Report (ISFR) 2017 on Monday, the environment ministry looked at the overall green cover (total forest and tree cover) of 8,02,088 sq km and pitched it as a success of multiple afforestation programmes.

Though this figure puts the green cover at 24.39% of India’s geographical area, this does not reflect a complete picture as it includes tree cover of 93,815 sq km, primarily computed by notional numbers.

In the past, studies have argued that the problem of depletion and over-exploitation of forests has taken a toll of India’s forests and their sustainability and the problem of simplifying a maze of rules and tune conservation with the needs of local communities remains a challenge Taking into account the density (canopy covering branches and foliage formed by the crowns of trees), forest cover is divided into ‘very dense’, ‘moderately dense’ and ‘open’ forest. The ‘very dense’ forest cover has increased over the last assessment of 2015, but the ‘moderately dense’ category reported a decline — a sign which environmentalists consider quite worrying.

Community governance

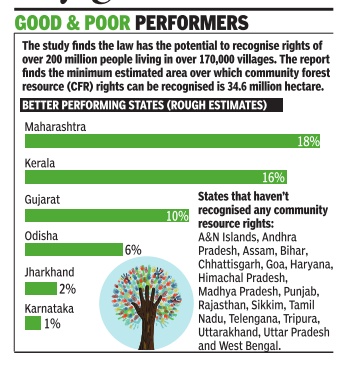

2016: 3% forest area under community governance

The Times of India, December 13, 2016

'Just 3% forest area under community governance'

Jayashree Nandi

Millions of forest dwellers in the country still do not have rights to conserve forests or access to forest resources. Ten years after the Forest Rights Act was passed by Parliament -a law that secures rights of forest dwellers and empowers them to protect forests -only about 3% of the potential forest area for community governance has been recognised, says a new study .

The `Promise and Performance: Ten Years of the Forest Rights Act' finds that the rights to manage, conserve and use forest resources by forest-dwelling tribes could have been recognised over an area of 34.6 million ha -an area larger than Madhya Pradesh -but has only been recognised in little over 1.1 million ha or only 3% of the potential.

The report by Community Forest Rights-Learning and Advocacy (CFR-LA) uses data from Census 2011 to assess total forest area inside and outside village boundaries (34.6 million ha) as the minimum potential area over which community forest resource rights could be recognised. This includes the minimum estimated forest area outside revenue village boundaries under custom ary use. The authors rely on data from the ministry of tribal affairs and state governments to compute the actual area over which rights have been recognised and it is estimated that the law can deliver community forest resource rights to about 200 million tribals and other forest dwellers living in 170,000 villages across the country.

The reason for such poor performance of the act, authors say is a “lack of political will“ and opposition by “forest bureaucracy“ or the ministry of environment and forests in handing over governance rights to the communities.

But why is this law important? Because it transfers decision making powers and forest conservation responsibilities to gram sabhas.The Niyamgiri case in Odisha has already established how gram sabhas can play a powerful role in protecting cultural and resource rights of indigenous communities after gram sabhas unanimously voted against bauxite mining in hills inhabited by the Dongria Kondhs.

2018: Success stories

India’s degraded forests are seeing a turnaround. From curbing rhino poaching to stopping tree felling and regenerating biodiversity, local communities have taken ownership of their forest homes in several states. The catalyst has been the Forest Rights Act of 2006 (FRA). The community forest resource (CFR) rights provision of the Act empowers forest-dwelling tribal communities to protect and manage forests. Community rights have been recognised in less than 3% of forests so far, says Community Forest Rights—Learning and Advocacy Group, a coalition of organisations. But some of the success stories have been documented by Centre for Science and Environment in its ‘People’s Forests’ report released last week. Shruti Agarwal of CSE says: “These are stories of community empowerment, which suggest that a new future of democratic forest governance is emerging. They create confidence in the ability of communities to manage and conserve their forests, and to generate sustainable livelihoods from them.”

MINDING THE FOREST AMRAVATI, MAHARASHTRA

In 2012, the tribal villages of Nayakheda, Payvihir, Upatkheda and Khatijapur were given charge of a highly degraded forest area of 990ha. Even the assistant conservator of forests of Amravati admits they “received the worst forests”. In the first year, villagers focused on planting bamboo and moisture conservation. They weeded out invasive species like lantana and non-useful trees like gum tree, planted by the forest department. In Payvihir village, they put a stop to the department’s auction of custard apple trees for a meagre Rs 1,500, and began marketing the fruit themselves, earning Rs 16,000 in the first year. “These villages have identified forest patches to be kept untouched from any intervention to observe the biodiversity and evolution of natural flora and fauna… Nayakheda has built watering holes for wildlife,” observes the CSE report. Payvihir gram sabha won the UNDP biodiversity award in 2014 for its work on decentralised forest governance.

BAMBOO BONANZA

NARMADA DISTRICT, GUJARAT

Villagers in Shoolpaneshwar Wildlife Sanctuary got CFR rights over 67% of the area in 2013-14. In the first year, 16 villages inside the sanctuary harvested a bumper crop of 96,319 MT of bamboo because of a good flowering season and earned Rs 185 million in revenue. A dozen villages decided to plough back 30% of the profits into forest protection and the rest into community development. The villagers have started working on ways to avoid forest fires, plant indigenous species, and manage water conservation.

WOMEN TURN EXPORTERS

KANDHAMAL, ODISHA

The lives of women in Madhikol changed after the village got CFR rights in 2016. The gram sabha, consisting of six men and six women, framed rules for patrolling of forests, protection from fires and sustainable harvest of forest produce. The practice of burning tendu bushes before the plucking season was stopped as the fire destroyed new plants of other important species. Earlier, tribal women would stitch siali leaves into plates and sell them to middlemen at a throwaway price of Rs 10 for 80 plates. In 2016, they formed a collective and began exporting the plates, earning Rs 50,000.

TREES BEFORE TENDU MONEY

Chandrapur, Maharashtra

Panchgaon was the first village in the district to get CFR rights. The village mandated each household to come up with at least five ideas for management of the forests. Eventually, 115 regulations were finalised. “Thus, the entire village was party to the decisions taken and the gram sabha’s success in governing its CFRs can be partly attributed to this inclusive and democratic approach,” says the report. Voluntary patrolling of forests is mandatory here. The most important decision of the gram sabha was a ban on removal of tendu leaves, forgoing huge revenue. “The collection of tendu leaves requires extensive lopping and setting fires in the forest, affecting the growth of trees and, in turn, the production of edible tendu fruit. Tendu leaves are used to make bidis which are not good for health. On the other hand, birds eat the tendu fruit; and so do we,’ Ramesh Tamke, gram sabha member told CSE researchers.

ASSERTIVE ADIVASIS

ALIPURDUAR, W BENGAL

The state government refuses to recognise the Adivasis’ CFR rights. But forest communities in north Bengal have been assertive. Twelve villages in the Chilapata forests of Coochbehar constituted gram sabhas who filed CFR claims in 2008-09 and passed resolutions to conserve forests and wildlife. In 2014, they resisted the forest department’s felling operations in elephant corridors as this could have aggravated man-animal conflict. “The village compelled the forest department to seek the permission of its gram sabha and carried out a survey of the trees marked by the department for felling. As more than 1,400 trees of native species would be cut down, the gram sabha refused permission,” states the report. It quotes Mahesh Rava from Kodalbasti village: “Our forests are better now. You should have seen them before 2008. We stopped illegal removal of boulders and sand from the rivers as well.” Villagers also claim incidents of rhino poaching have reduced significantly because of their patrolling measures.

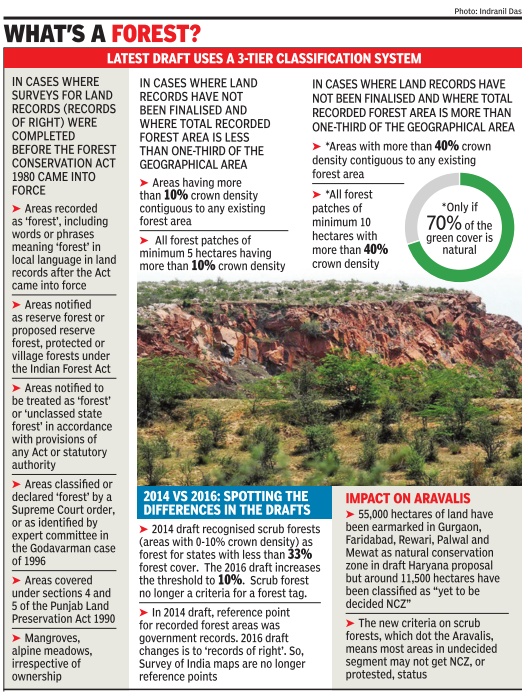

Definition of a forest in India

See graphic, ' The definition of a forest in India '

Diversion of forest land for non-forest purposes

Guidelines for diverting forest land

The economic viability of any development project that involves diversion of forest land may now reduce with the environment ministry coming up with new costbenefit analysis guidelines.

The new guidelines submitted to the National Green Tribunal (NGT) by the ministry comprise a number of new costs for diversion of forest land including possession costs and habitat fragmentation costs.

The enhanced cost of diverting forest land will come into effect only when the process of arriving at the net present value (NPV) of forests, as prescribed by the Supreme Court in 2008, is re vised. The new guidelines, however, may highlight the steep environmental costs of diverting forests, say officials and help the ministry make a judicious decision.

According to the new guidelines, the ecosystem service cost of diversion will be assessed based on the NPV formula. While 30% of the NPV will be added to the diversion cost as the cost of “possession of forest land“, an additional 50% of NPV cost will be added as “habitat fragmentation cost“. Guidelines say 10% of NPV cost will be added for loss of animal husbandry productivity and soil moisture conservation costs.

The environment ministry till now was doing the cost-benefit analysis based on guidelines drafted in 2004, which, experts say , are outdated. The ministry came up with new guidelines in compliance with the National Green Tribunal (NGT's) order a few years ago in Uttarakhand activist Vimal Bhai's petition against displace ment of forest dwellers due to a hydroelectric project.

“The new cost-benefit guidelines account for various ecological services like water recharge, nutrients in the soil, carbon sequestration and others. They also account for the cost of possession of forest land by the project proponent. Now the viability of certain projects on forest land will reduce,“ said an environment ministry official, requesting anonymity .

The government, however, has not revised the NPV (amount to be paid by project proponents) despite court orders. They were to revise it every three years.

Vimal Bhai, the petitioner, however, said he was apprehensive if the new guidelines will actually be imp lemented. “The government agencies have a very poor record of implementing guidelines,“ he said.

Referring to a clause in the new guidelines which says the forest dwellers will be paid 1.5 times of what they would have earned in two years towards social cost of rehabilitation, Vimal said, “Their income cannot be quantified because their life is completely dependent on the forest.“

Madhu Verma of the Indian Institute of Forest Management in Bhopal said “implementation or assessing the viability of a project is up to the ministry . But the new guidelines do account for possession of forest land.The social costs of forest diversion are enormous and difficult to quantify .“

2014: 36k ha for infra projects

The Times of India, Apr 29 2015

36k ha of forest land diverted for infra projects in 2014

The Centre had given its approval for diversion of 35,867 hectares of forest land in a total of 783 cases, involving roads, railway lines and other infrastructure projects in 2014 Sharing the forest diversion figures, the Centre informed Parliament that the maximum forest land of 9,830 ha was diverted in Madhya Pradesh, followed by Odisha (4,516 ha), Andhra Pradesh (3,334 ha), Chhattisgarh (3,236 ha), Jharkhand (2,989 ha) and Maharashtra (2,380 ha).

However, there was no diversion of forest land in Jammu & Kashmir, Kerala, Megh alaya, Nagaland, Tamil Na du, Telangana, Pondicherry Daman and Diu and Lakshad weep last year.

Responding to a different query on whether the tribal af airs ministry had raised ob ections to the dilution of forest aw, Union environment min ster Prakash Javadekar, in his written response, said, “The process of inter-ministeria consultation is still going on.“

He said the environment ministry has formulated revised draft guidelines on ensuring compliance with the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, in cases of diversion of forest land for nonforest purpose under the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980.

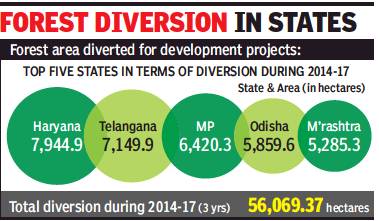

2014-’17: Haryana, Telangana, MP worst offenders

From: Vishwa Mohan, Agrarian Haryana tops diversion of forest land; Telangana, MP next, December 26, 2017: The Times of India

Haryana does not have much area under forest cover — most of its land (80%) is under cultivation — but it still diverts more forest land than any other state for non-forestry purposes, such as construction, infrastructure and industrial projects.

Along with Telangana, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and Maharashtra, Haryana accounted for more than 50% of the total diversion of forest area (56,069 hectares or 560.69 sq km) for non-forestry projects in the entire country between 2014 and 2017, according to environment ministry figures.

At the same time, however, afforestation of 93,400 hectares (934 sq km) of land was carried out in Haryana during the period, though the new plantations will take years before they can be said to have replaced the older diverted forest land.

Only 3.6% of Haryana land is notified forests

Figures, released by the environment ministry, showed that Haryana, which has only 1,584 sq km of forests, had diverted 79.44 sq km (7,944 hectares) despite the fact that the state had reported overall decline in its forest cover in 2015 as compared to 2013.

Haryana is primarily an agricultural state with almost 80% of its land used for cultivation. The geographical area of the state is 44,212 sq km which is 1.3% of India’s geographical area. Only 3.58% of the state’s geographical area comes under notified forests.

According to the India State of Forest Report 2015, forestry activities in Haryana were dispersed over the rugged Shivalik hills in the north, Aravalli hills in the south, sand dunes in the west and wastelands, saline-alkaline lands and waterlogged sites in the central part of the state.

The figures showed that four of top five forest diverting states reported a decline in overall forest cover in 2015 as compared to 2013. Only Odisha showed a minor increase (of 7 sq km or 700 hectares) in its forest cover in 2015 as compared to 2013.

There is a government policy for compensatory afforestation whenever forests are diverted for non-forestry purposes like mining, dams, industrial and infrastructural projects. However, a recent report of Community Forest Rights-Learning and Advocacy (CFR-LA) — a group of grassroots organisations, researchers and academicians — found several loopholes in ongoing compensatory afforestation programmes.

It also shared documentary evidence with the Parliamentary Committee on Petitions, highlighting that majority of compensatory afforestation projects across 10 states (which the group studied) was done on forest land instead of non-forest land in clear violation of guidelines under the Forest Conservation (FC) Act, 1980.

Compensatory afforestation under the FC Act must be undertaken on non-forest land in the same district where the forest was diverted for non-forestry purposes.

91,798 ha (918 sqkm) diverted: 2017, Jan-Aug

Vijay Pinjarkar, 92,000 ha of forests opened up, October 9, 2017: The Times of India

The forest ministry has been on a land diversion spree recommending a massive 91,798 hectare area (918 sqkm) to be diverted from January to August in 2017.

The decision was taken by the Forest Advisory Committee (FAC) of the ministry of environment, forest and climate change (MoEF & CC), raising serious concerns for the environment at a time when forested lands are being considered valuable carbon sinks.

FAC has diverted forest area towards 70 projects, which is equivalent to four times the area of Maharashtra side of Pench Tiger Reserve (257 sqkm). A review of the FAC min utes by members of a Delhi based facility -the Environ ment Impact Assessment Re source and Response Centre (ERC) -revealed that in May , 61,278 hectare (613 sqkm) was recommended in one meeting alone.

“FAC seems to be in a tear ing hurry to divert forest land. This can be gauged from the fact that in August, three meetings were held to clear projects involving 15,027 hectare area. Interestingly, the compilation of area excludes proposals up to 40 hectare which are dealt with at the regional level,“ said Pushp Jain of the ERC.

During the period, FAC considered 134 proposal, out of which it rejected just two.70 projects were recommended for diversion, while the rest were deferred for want of more information. Among the major proposals that were cleared included the controversial river linking Ken-Betwa main project which had diversion of 6,017 hectare of forest land in favour of National Water Development Agency (NWDA), in Chhattarpur near Panna and Ti kamgarh in Madhya Pradesh.

Jain said the project is going to cause irreparable damage to Panna Tiger Reserve.“The project is simply senseless as no account of alternative sites was considered and study does not recommend the project,“ he said.

ERC had opposed Ken-Betwa proposals as they are illegal in nature as per the section 35 (6) of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 and a great loss of forest and wildlife.

ERC's Terence Jorge said the recommended projects do not include 695.72 hectare forest land for limestone mining at Shedwai in Chandrapur district. “But this was done owing to legal complications and not considering the area which falls in the Tadoba-Kawal tiger corridor,“ he said.

Forest fires

Number of forest fires: 2013-16

See graphic, ' Number of forest fires in the country, 2013-April 2016, year-wise… '

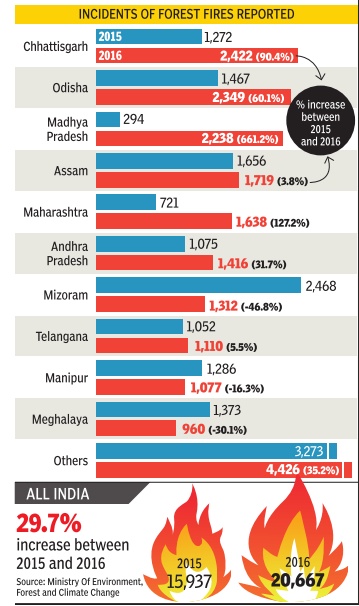

Number of forest fires: 2015-16

See graphic, ' Incidents of forest fires reported, 2015-16, state-wise... '

Hinduism, Buddhism and forests

The Times of India, June 9, 2016

Devdutt Pattanaik

In the Sama Veda, the hymns of the Rig Veda are turned into melodies.

These melodies are classified into two groups: the forest songs aranya-gaye-gana or Forest Songs, and grama-gaye-gana or Settlement Songs.This divide plays a key role in the understanding of dharma.

Forest is the default state of nature.In the forest, there are rules. The fit survive and the unfit die. The stronger, or the smarter, have access to food. The rest starve. There is no law, no authority and no regulation. This is called `matsya nyaya' or law of the fishes, the vedic equivalent of the law of the jungle. This is prakriti, visualised as Kali, the wild goddess who runs naked with unbound hair, of the puranas.

Humans domesticate the forest to turn the forest into fields and villages for human settlement. Here, everything is tamed: plants, animals, even humans, bound by niti, rules; riti, tradition; codes of conduct, duties and rights.Here, there is an attempt to take care of the weak and unfit. This is the hallmark of sanskriti or civilisation, visualised as Gauri, the docile goddess who is draped in a green sari, and whose hair is tied with flowers, who takes care of the household.

The Ramayana tells the story of Rama who moves from Ayodhya, the settlement of humans, the realm of Gauri, into the forest, the realm of Kali. The Mahabharata tells the story of the Pandavas who are born in the forest, then come to Hastinapur, and then return to the forest as refugees, and then once again return to build Indraprastha, then yet again return to the forest as exiles, and finally , after the victory at war, and a successful reign, they return to the forest following retirement.

As children, we are trained to live in society that is brahmacharya. Then we contribute to society as householders grihastha. Later we are expected to leave for the forest vanaprastha, and then comes the hermit life or sanyasa, when we seek the world beyond the forest.

According to the Buddhist Sarvastivadin commentary , Abhidharma mahavibhasa-sastra, forest or vana, is one of the many etymologies of the word `nirvana', the end of identity , prescribed by Buddhist scriptures, which is the goal of dhamma, the Buddhist way .

Rama lives in a city, and so does Ravana. But Rama follows rules. Ravana does not care for rules. In other words, Ravana follows matsya nyaya though he is a city-dweller, a nagara-vasi. That is adharma. If Ravana uses force to get his way, Duryodhana uses his cunning, also focussing on the self rather than the other. This is adharma.Dharma is when we function for the benefit of others. It has nothing to do with rules. Which is why Krishna, the rule-breaker, is also upholding dharma, for he cares for the other.

In the forest, everyone is driven by self-preservation. Only humans have the wherewithal to enable and empower others to survive, and thrive. To do so is dharma. It has nothing to do with rules or tradition. It is about being sensitive to, and caring for, the other. We can do this whether we are in the forest, or in the city. And so it is in the vana or forest, that Krishna dances with the gopikas, making them feel safe even though they are out of their comfort zone.

Without appreciating the forest and the field, Kali and Gauri the animal instinct and human capability any discussion of dharma will be incomplete.

See also

Forests: India