Employment, unemployment: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.

|

The magnitude of the problem

2011: 11.3 crore persons seeking employment

Army of jobseekers now 11cr-strong

Subodh Varma

The Times of India Sep 24 2014

Constitutes 15% Of Working Age People, Spread Over 28% Of India's Families: Census

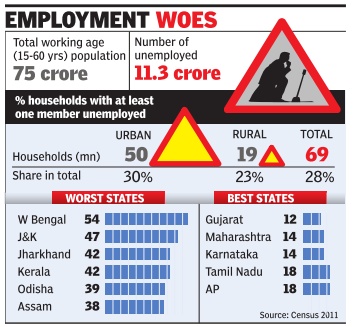

Over 11.3 crore persons are “seeking or are available for work“, that is, they were unemployed, according to Census 2011 data released on Tuesday .

This huge number made up around 15% of the working age population of about 74.8 crore in the 15 to 60 years age group.These unemployed persons were distributed over nearly 7 crore families or households.That's about 28% of all households in the country .

By categorizing persons as “seeking or available for work“ the Census has differentiated them from those who are not in the job market, which includes housewives and students among others.

This appears to be an alltime high for Census years. In 2001, about 23% of households had members that were unem ployed. Within a decade, this had risen to 28%. In the past three years, no particular spurt in employment growth or poli cies that would catalyse job creation have emerged and the situation continues to be dire.

These exceptionally high unemployment levels are likely to have contributed to the severe loss UPA suffered in the 2014 polls. Many pre-election opinion polls had underlined that unemployment was a key issue with voters. These stark figures would also be a wakeup call for the new Modi sarkar.

As reported previously by TOI, over 20% of youth between 15 to 24 years of age were jobless and seeking work according to Census 2011 data released earlier. In absolute terms, this army of unemployed youth is about 47 million.

The number of unemployed persons is actually more than 113 million because the Census office has released data in terms of how many persons per household are seeking or available for work, and the highest number in that is “more than 4“. For the purpose of the present computation, this has been taken as four persons only . There has been a distinct shift in the employment pattern since 2001. In most states, and nationally , the situation is relatively better in urban areas than rural. Nationally , 23% of urban households reported that they had at least one member unemployed while in rural areas this share went up to 30%. In 2001, the difference was not so much. The reason behind this appears to be the deep agricultural crisis.

Statewise unemployment figures reveal that while most states have approximately the same proportion of households with some member unemployed as the national average, some states have much higher rates. These include Jammu & Kashmir with about 48% households having unemployed persons, Bihar (35%), Assam (38%), West Bengal (54%), Jharkhand (42%), Odisha (39%) and Kerala (42%).

2016: people seeking work

The Times of India, Mar 27, 2016

Subodh Varma

In the 2016 Budget session of Parliament, there was an eerie silence on one of the biggest problems facing the people — jobs. Both the Rail Budget and the Union Budget speeches mentioned jobs a handful of times but mostly in reference to future prospects. The debates, including the PM's interventions, followed the trend with hardly any worry about jobs. Meanwhile, in the real world, the job situation is not a happy one. Although current employment statistics are not generated in India, applications in the job guarantee scheme have touched an all-time high and a quick survey of eight industries done every quarter by government indicate a dire situation. Macroeconomic parameters too are not showing any hope. The number of people who apply for work in the job guarantee scheme is a good measure of the employment situation in rural areas.

Till the third week of March 2016, a staggering 8.4 crore persons had demanded work under MGNREGS. That's a 15% increase from the 7.3 crore who demanded work last year. This is a symptom of large scale scarcity of jobs because the wage employment scheme provided only 43 days of work on average in a whole year — instead of the 100 days guaranteed under the scheme —and that too manual labour. Of those who applied, nearly 1.6 crore or 19% were not given work — the highest turn-back ever seen in this scheme. So, the job situation in rural areas doesn't appear to be very healthy.

Another partial measure of recent employment trends is provided by a quarterly survey of eight industries by the Labour Bureau. The last such survey result was released in March 2016 covering June to October of 2015. After the NDA government took over, just 4.3 lakh jobs have been added between July 2014 and October 2015 — lower than the immediately preceding 15 months and the same as the corresponding period of 2012-13 under UPA. Of these, the bulk of jobs have been in IT-enabled services (ITES) and the BPO sector. Besides these two indicators, some of the big economic indicators too are not presenting a very optimistic picture. The index of industrial production measures how industrial production is changing — if it rises, so does employm ent, and if it slows, creation of jobs is affected. Between April 2015 and January 2016, the IIP grew by just 2.7%. In the previous year, the first year of this government, it had grown by 2.6%. For eight core industries like coal, oil, gas and steel, which make up 38% of the IIP, the growth from April 2015 to January 2016 was just 2%.

Agricultural output has meanwhile sunk with gross value added growing at a mere 1.1% in 2015-16, as per latest estimates by the Central Statistical Office. This comes after a decline of 0.2% in 201415. This is the devastation of two successive droughts. Services sector continues to grow with its output rising by 9.2% in 2016.

The bottomline is that jobs remain elusive, and measures to create jobs — through infrastructure development or Make in India — are still to show results.

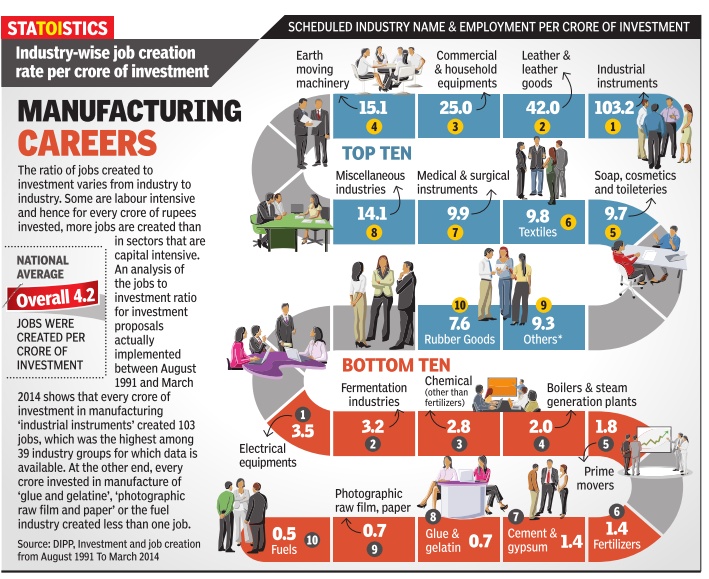

Jobs to Investment ratio

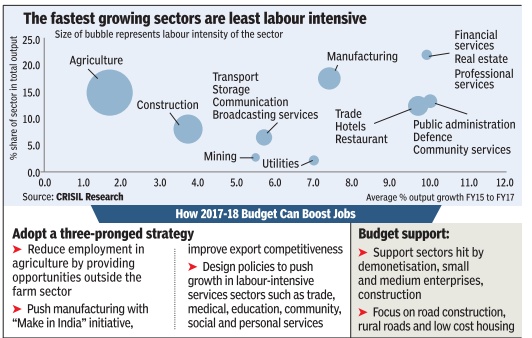

See graphic.

Employment creation

The main sectors

The Times of India, Sep 11 2016

Subodh Varma

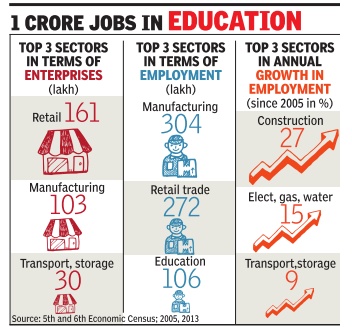

The retail-friendly Indian: A shop for every 15 families

Indians continue to show their entrepreneurial spi rit -by opening more and more shops. With over 1.6 crore retail shops in the country -about one for every 15 families -this sector of work outguns every other.

Manufacturing, considered the backbone of prosperity for any economy , is second to retail with over 1 crore units. But manufacturing employs over 3 crore people beating retail trade, which has about 2.7 crore.

Transport companies, warehousing, hotels and eateries, and healthcare-related enterprises are other major occupations, while educational enterprises have emerged as major employers with over 2 million such businesses employing nearly 1.1million people.

These facts emerge from the 6th Economic Census con ducted by the government in 2013, detailed results of which were released earlier this year. The economic census counts all kinds of enterprises across the country except cultivation of crops and their ca re and protection. In this census, some 5.8 crore enterprises were counted, employing over 13 crore people. The previous one was done in 2005. The sector that has really boomed is construc tion, with employment growing at 27% per year. This is 2013 data so it will not reflect subsequent travails of the sector. Trade is in itself arguably the biggest employer if one adds up wholesale trade and sale and repair of motor vehicles which the census counted separately .

Putting all three together one gets about 1.8 crore enterprises employing 3.2 crore people, nearly 35 percent of all non-agricultural and non-extractive industries. This picture of a bustling economic hive with vast numbers involved in diverse enterprise building needs to be tempered with some economic cold water. Nearly 96% of all enterprises employ one to five workers, with just 1.4% employing more than 10 workers.

Compared to 2005, the share of enterprises in the 1-5 category has marginally increased. This indicates the atomised and dispersed nature of entrepreneurial activity, which, especially in the case of manufacturing, speaks of a rather low economic level. Of the three cr manufacturing enterprises, about a third, that is one crore, are working without any hired worker.

Economists have suggested earlier that retail trade is in fact a last resort for families seeking to boost incomes by selling a few items in villages or weekly haats. This transient nature of retail trade seems to be confirmed by the fact that 25% of these establishments are run from within homes and 17% are run without any fixed structure.

2016, Apr-Sept: 0.5% jobs added in 8 key non-farm sectors

Just over one lakh jobs were added between April 1 and October 1 last year in eight key non-farm sectors of the economy ranging from manufacturing and construction to ITBPO, education and health, according to a recent government report. Is this good or bad?

Considering that these eight sectors together employ over two crore workers, the net addition of new jobs amounts to a mere half a per cent of the total. So, it's bad news for the economy and another red flag for the government. The report in question is the third quarterly employ ment report, which was revamped by the government last year with new sectors included and a larger sample size of over 10,000 establishments.

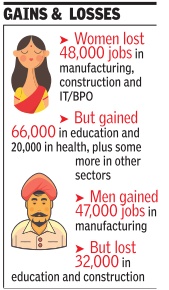

The first report, released last year, set the baseline of employment as on April 2016. The report shows that employment is not only inching up at a painfully slow pace but also that aggregate figures hide more severe upheavals. For instance, almost three quarters of 1.09 lakh new jobs added are confined to two sectors -education and health, which added 82,000 new jobs. But the most worrying thing is manufacturing jobs grew by just 12,000 in six months -a rise of 0.1%. This sector, the backbone of the non-farm economy , employs nearly 50% of workers in the selected eight sectors. It has been the focus of the `Make in India' and `Skill India' programmes, as also of efforts to woo FDI. The Index of Industrial Production (IIP), re leased monthly by the government, confirms this dire situation with a rise of a mere 1% between January 2015 and January 2017.

According to latest data from the RBI, the same period saw gross bank credit to industries increasing by a mere 0.3%. This includes credit disbursals to micro, small, medium and large industries and together makes up nearly 40% of all non-food credit. The meager increase in credit to industry is a symptom of the flagging growth in manufac turing, which is also reflected in lack of job growth.

Further confirmation comes from second advanced estimates of national income and expenditure released by the government last month. Growth in investment in fixed capital known as gross fixed capital formation dipped by a factor of 10 between 2015-16 and 2016-17 from 6.1% to a shocking 0.6% in 2016-17. This implies that the corporate sector is not investing in new production arrangements.

Growth in gross value added (GVA) at basic prices -a measure of actual production -has slipped from 7.8% in 2015-16 to 6.7% in 2016-17.

Unemployment

2004-12:Unemployment rate: area, category and gender-wise

Apr 25 2015

Ranks of jobless SCs, OBCs in villages swell

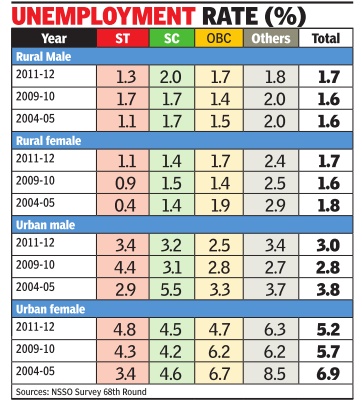

Mahendra Singh

Unemployment increased, if marginally , among rural male inhabitants of the scheduled castes (SC) and other backwards castes (OBC) between 2009-10 and 2011-12, a survey by the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) has discovered. In this period, the unemployment rate for men living in villages went up from 1.7% to 2% among SCs, and from 1.4% to 1.7% among OBCs.The unemployment rate decreased marginally , from 1.7% to nearly 1.3%, for STs, and 2% to 1.8% for those who comprise `Others' category.

Among women living in rural areas, the unemployment rate for STs increased from 0.9% in 2009-10 to 1.1% in 2011-12, and for OBCs, from 1.4% to 1.7%. It remained almost at the same level for SCs (1.5% in 2009-10 compared to 1.4% in 2011-12) and `Others' (2.5% in 2009-10 compared to 2.4% in 2011-12). In cities and towns, the unemployment rate among men decreased for STs (from 4.4% in 2009-10 to 3.4% in 2011-12) and OBCs (from 2.8% to 2.5% for the period) while remaining at the same level for SCs (3.1% in 2009-10 to 3.2% in 2011-12). The unemployment rate for `Others', however, increased from 2.7% to 3.4%.

Unemployment has increased among ST and SC women living in urban areas, going up from 4.3% in 2009-10 to 4.8% in 2011-12 for STs, and from 4.2% to 4.5% for SCs.However, unemployment decreased among OBC women living in cities and towns (from 6.2% to 4.7%) and remained at the same level for `Others' (6.2% in 2009-10 and 6.3% in 2011-12). In a nutshell, the unemployment rate in 2011-12 for urban women was lowest among SCs, while their ST counterparts were better placed in villages. Among males living in urban areas, unemployment was worst for STs, while SCs faced the highest rate in villages.

2009-12: Joblessness on rise

Non-NREGS work paying more: Govt survey

TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

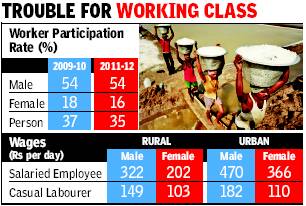

Between 2009-2010 and 2011-2012, the proportion of people working slipped slightly in India, and the share of unemployed persons ticked up, a government report released on Thursday revealed. In 2009-10, 36.5% of the population was gainfully employed for the better part of the year. By 2011-12, the proportion of such workers had dipped to 35.4%. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate went up from 2.5% to 2.7%.

These findings form the crux of a survey on employment and unemployment carried out by the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO). The survey covered over one lakh households and was carried out between July 2011 and June 2012. The pan-India figures hide a deepening chasm between job opportunities for men and women. While the share of employed men remained roughly constant between 2009 and 2011, women’s employment dropped from 18% to 16%.

Loss of jobs

This may appear a small decline but translated into real numbers the crisis in employment is starkly revealed. In rural areas, about 90 lakh women lost their jobs in the two-year period. This would have been catastrophic but for the fact that in urban areas about 35 lakh women were added to the workforce.

Men joined the workforce in both urban and rural areas, though they got many more opportunities in towns and cities than in villages. Men’s participation in the workforce jumped from 99 million to 108 million in urban areas and from 228 million to 231 million in rural areas.

Unemployment

Kerala had the highest unemployment rate of close to 10% among the larger states. West Bengal (4.5%) and Assam (4.3%) were other large states with relatively high unemployment rates. Among smaller states, Nagaland had a staggering jobless rate of 27%, but this may be compromised data as surveys are difficult in strife-torn areas. Tripura too had a high unemployment rate of over 15%.

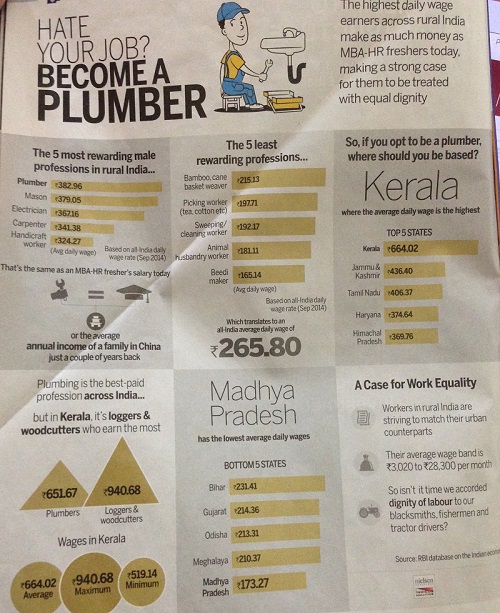

Wages

The report also contains striking information on daily wages of casual labourers and regular or salaried employees. In the government’s jobs scheme (MGNREGS), male workers were getting an average of Rs 112.46 per day, while in non-MGNREGS public works the rate was Rs 127.39, and in non-public works it was Rs 149.32. For women, the averages were more similar at about Rs 102 to Rs 110, though lower than men for the same work. This appears to go against a widely held belief that MGNREGS rates are setting the standard for all other wages in rural areas.

The wide gulf in urban and rural wage rates explains why people are migrating to live in cities. A male casual labourer earned about Rs 150 per day in rural areas, but his urban counterpart got Rs 180 per day. Similarly, a salaried employee could earn about Rs 300 per day in rural areas but in urban areas the same would shoot up to nearly Rs 450.

2014: Unemployment among skilled workers

The Times of India, Jul 20 2015

Subodh Varma

Survey: Even among skilled workers, joblessness is high

`14.5% end up without work after training'

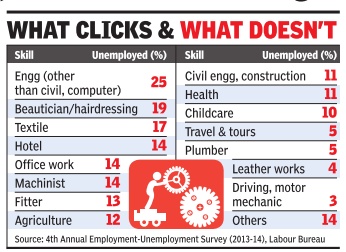

Among those who got formal training in establishments like Industrial Training Institutes or other Skill Centres, the unemployment rate was high -at 14.5% -compared with 2.6% overall, according to a survey done by the Labour Bureau in 2014 and released in 2015.

In a revealing breakdown of skills and the corresponding rate of unemployment, the survey found that except for a handful of trades like leather work, plumbing, motor driving and tourtravel operations, all other categories of skilled persons exhibited double-digit unemployment figures. Some of these are shocking: over a quarter of those who had done engineering diplomas in disciplines other than civil and computers were unemployed. Nearly 17% of those with textile-related training and over 14% with machine operator skills were without jobs.

Unless new jobs, especially in the manufacturing sector, are created, imparting skills to millions will not solve the problem, says IIT-Delhi's Jayan Jose Thomas, who has researched the Indian employment scenario extensively. Existing industry does face a skills gap. That's what entrepreneurs and industrialists keep telling me. So, imparting skills will help somewhat. But the primary thing is to have a policy for industrial growth that will create millions of new, decent job opportunities,“ he told TOI.

About 12 million people join the workforce every year in India. But an analysis of job growth over the past nearly two decades by Thomas, using NSSO and census data, shows that on an average, only 5.5 million new jobs have been added every year in this period.

Labour Bureau data shows that unemployment rates are higher among those with higher educational qualifications. While the overall unemployment rate was reported at 2.6% among the over-15 age population, for postgraduates, it was 8.9%, for graduates 8.7% and for diploma or certificate holders, 7.4%. Experts believe that this could be because qualified persons seek better wages and hence may remain unemployed for a longer period while seeking the best options.

Industrial employers often prefer to employ workers with no formal training but adequate experience over say ITI products, again because of wage issues. According to University of California, Santa Barbara's Aashish Mehta, who has studied the skill gap issue, the decision is more a commercial one than a skill level issue.

The average daily wage of an urban diploma holding worker was about Rs 524 for men and Rs 391 for women according to an NSSO report.Men who have studied up to senior secondary make 45% more and women 28% more.But compared to graduates, the diploma holder will get 56% less if male and around 54% less if female. This gives an indication of how employers will make choices, and may also hint at families making educational trajectory choices. The unemployment rates are higher among those with higher educational qualifications. Experts believe that this could be because qualified persons seek better wages and hence may remain unemployed for a longer period while seeking the best options

2014-15: rising unemployment

The Times of India, Jun 25 2015

Ambika Pandit

8.5 LAKH IN 2013 - Number of unemployed rising

Unemployment is clearly a problem in the city but what is more worrying is that between 1995 and 2013, the number of unemployed holding diplomas of various courses has more than doubled from 21,705 to 44,934. This data--part of Delhi Government's Economic Survey 2014-15--raises a serious question about the quality and future of diploma courses and vocational training programmes floated from time to time. In 2013, Delhi had 8.5 lakh unemployed people, significantly lower than the 11.3 lakh recorded in 1997. However the data reflects a very worrisome trend from 2010 onwards as, after falling to 4.1 lakh in 2009 the number has risen steadily . It was 4.9 lakh in 2010, became 6.4 lakh in 2011 and then rose to 7.7 lakh in 2012.

Not only is the rise worrisome but also the educational status of those reeling under the effect of unemployment is a cause of concern and will be a major challenge for the Kejriwal government that won support from youth on the promise of “degree, income aur wi-fi“. The AAP government has talked about vocational training and skill development as part of its long-term education plan.

The Economic Survey makes it clear that many di ploma holders are not getting jobs easily . In 2009, the num ber of unemployed in this category had gone down to 8,766 but rose to 23,361 in 2010 reached 37,554 in 2011 and 44,934 in 2013. The authorities need to fo cus on the vocational courses and diplomas offered in the city. These need to be clearly aligned with the needs of the market. The data also shows that most of the unemployed have studied up to graduation or less. The number of unem ployed in this category in 2013 was 4.9 lakh, down from 5.2 lakh in 1995. However, the large number of jobless youths who have studied up to Class XII shows the lack of courses linked to livelihood.

The number of unemployed graduates and post-graduates in 2013 was 1.9 lakh.Those below matriculation and seeking jobs added up to 1.3 lakh.

2015: Joblessness at 5-year high

The Times of India

The Times of India

Subodh Varma, Joblessness at 5-year high, Oct 01 2016 : The Times of India

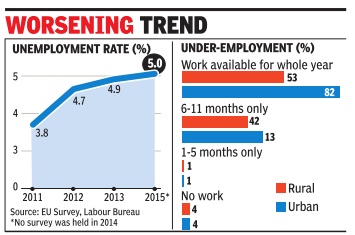

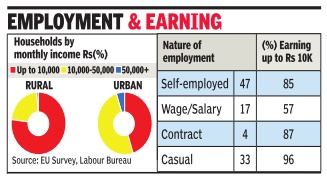

Joblessness in India is run ning at a five-year high of 5% of the 15-plus-years workforce. Over a third of working people are employed for less than a year and 68% of households are earning up to only Rs 10,000 per month, according to a new employment-unemployment (EU) survey report conducted by the Labour Bureau.

Over 7.8 lakh persons in 1.6 lakh households were surveyed across the country between April and December 2015. Expectedly, urban areas continue to provide more and better paying jobs compared with the rural areas. While 82% of job seekers get year-round jobs in urban areas, just 53% of rural job seekers manage to get such security. About 42% of workers in rural areas work for less than 12 months in a year, a result of dependence on seasonal agriculture work. Unsurprisingly, this means that 77% of the rural households end up with an average monthly income of less than Rs 10,000. In urban areas, about half the households earn between Rs 10,000 and Rs 50,000 per month.

These findings of the first large sample survey after the Modi government took power in June 2014 show that even after more than a year of seeing the new government's policies in action, the situation on the ground continues to be dire and effectively the same as in the preceding UPA's rule. It shows a continuation of a distressing job situation -and hence economic status -that was reflected in earlier surveys like the 68th round of NSSO and the Socio-Economic & Caste Census (SECC) in 2011-12.

What does 5% unemployment and 35% underemployment mean in hard numbers? Projecting from Census 2011 figures, India had a 15-years-and-older labour force of about 45 crore.So, 5% of that is a whopping 2.3 crore persons. In addition, there are those who work but not for the whole year, signifying hidden unemployment. This works out to nearly 16 crore persons. Women's employment continues to stagnate with 8.7% of women in the labour force without jobs.

Comparison to previous surveys done by the labour bureau show that the unemployment rate rose from about 3.8% in 2011to 4.9% in 2013. This was a period of relative economic slowdown compared to earlier in the decade. But growth has been recorded at 7.3% in 2015-16 -yet the jobs situation has worsened. The Modi government's pro nouncements for job creation, like Make in India, Start-Up India and Digital India do not seem to have had the desired impact.

The labour bureau survey also found that about 47% of the working population was self-employed.This would be mostly farmers, shopkeepers, and enterprise owners. But the low economic level of this section is revealed by the fact that 85% of such households had a monthly income of less than Rs 10,000.

Another 33% of households earn their living through casual employment. Regular wage or salary earning households make up just 17% of all, although this is the kind of work that pays more with 43% of peoploe earning more than Rs 10,000.

Employment creation is inadequate

Salary growth, 2008-16: 0.2%; GDP growth 63.8%

India's salary growth at 0.2%, GDP gain of 63.8% since 2008, PTI | Sep 15, 2016

- India has seen a salary growth of just 0.2 per cent since 2008.

- However, Indian econony grew by 63.8% since 2008.

- China recorded the largest real salary growth of 10.6% in this period.

- The US suffered one of the worst salary recoveries among developed nations.

India has seen one of the lowest pay rises since 2008.

NEW DELHI: India has seen a salary growth+ of just 0.2 per cent since the great recession eight years back, while China recorded the largest real salary growth of 10.6 per cent during the period under review, says a report.

According to a new analysis by the Hay Group division of Korn Ferry, India's salary growth+ stood at 0.2 per cent in real terms, with a GDP gain of 63.8 per cent over the same period.

During the period under review, China, Indonesia and Mexico had the largest real salary growth at 10.6 per cent, 9.3 per cent and 8.9 per cent, respectively.

Starting salaries in India amongst lowest in Asia-Pacific: Study

Meanwhile, some other emerging markets including Turkey, Argentina, Russia and Brazil had the worst real salary growth at (-) 34.4 per cent, (-) 18.6 per cent, (-) 17.1 per cent and (-) 15.3 per cent, respectively.

"Most emerging G20 markets+ stood at either one end of the scale or the other either amongst the highest for wage growth, or amongst the lowest. However, India stood right in the middle, with all the mature markets," the report said.

The report further noted that Indian wage growth is the most unequal.

"Of the countries we looked at, Indian wage growth was by far the most unequal - people at the bottom are 30 per cent worse off in real terms since the start of the recession; whilst people at the top are 30 per cent better off," Benjamin Frost, Korn Ferry Hay Group Global Product Manager - Pay said.

Strong wage growth for senior jobs is mostly because of skill shortages for key professional and managerial roles; and the increasing connection to a more globalised pay market at the senior levels - a market where India still pays less than most countries, but is catching up fast, Frost said.

Regarding the poorer wage growth at the bottom, the report noted that it is more because of an oversupply of people.

"India has made less progress than some other countries in bringing high value jobs to the country. This has led to poor job growth, therefore an oversupply of un/semi-skilled people, and poor wage growth," Frost said.

2004-2010: Jobless growth?

‘Jobless growth’ during UPA-1, admits Centre

Self-Employed Dropped From 56.4% To 50.7% Of Workforce

Rajeev Deshpande TNN

New Delhi: Some 20 months after hotly contesting data on UPA-1’s “jobless growth”, the government has admitted to lack of substantial increase in employment between 2004-05 and 2009-2010, with the selfemployed workforce shrinking from 56.4% to 50.7% of the total workforce.

In absolute numbers, the self-employed decreased from 258.4 million to 232.7 million in this period while regular salaried workers rose from 69.7 million to 75.1 million. The ranks of casual labour rose from 129.7 million to 151.3 million. In all, the total workforce increased from 457.8 million to 459.1 million, a rise of just 0.3% over this period.

The ministry of planning has identified limited flexibility in “managing” the workforce, high cost of complying with labour regulations, poor skill development and a vast unorganized sector as reasons for dissatisfactory growth in employment.

Responding to Parliament’s finance standing committee’s query on why India was not creating enough productive jobs, the ministry said while the number of salaried employees increased, the selfemployed segment declined.

Interestingly, the ministry referred to the same 66th round of the National Sample Survey Organization that irked the government in June 2011 with Planning Commission deputy chairperson Montek Singh Ahluwalia slamming the report as inaccurate.

The controversy deeply embarrassed the ruling coalition as the data seemed to negate the Manmohan Singh government’s “inclusive growth” slogan despite policy initiatives intended to make growth less uneven.

Under official pressure, the NSSO later put down the employment statistics to factors like rising incomes resulting in women choosing to stay at home instead of taking up physically challenging jobs.

Yet , the planning ministry that has told the finance committee “India had an average growth rate of 7.9% in the 11th plan. However, this growth did not lead to increase in employment opportunities”.

Stating that the NSSO data exhibited a shift in employment status, the ministry said in the period 2004-05 to 2009-10, the percentage of regular salaried workers increased from 15.2% to 16.4% and there was a jump in casual labour from 28.3% to 33%. It indicates that informal employment that accompanies new real estate development, industry and urbanization has lagged.

This would include service providers like road side eateries, local transport, small shops and services like appliance repair.

The planning ministry did not explain the jump in casual labour but this could due to the rural employment guarantee scheme, although the government has also argued that the trend contradicts claims of slow employment.

The numbers may look even less flattering when the next bunch of statistics is available in view of the plummeting growth.

The government has listed measures like boosting manufacturing, developing skills, promoting labour intensive sectors and simplifying labour laws as an antidote to the employment logjam.

GOING SLOW

Percentage of self-employed dropped from 56.4% of total workforce in 2004-05 to 50.7% in 2009-10

Percentage of regular employees rose from 15.2 to 16.4 and of casual labourers from 28.3 to 33

In absolute numbers, number of self-employed was 258.4m in 2004-05 and 232.7m in 2009-10

There were 69.7m regular workers in 2004-05 and 75.1m in 2009-10

Casual labourers rose from 129.7m to 151.3m

Total workforce rose from 457.8m in 2004-05 to 459.1m in 2009-10, an increase of just 0.3% Casual labour grew from 28% to 33%

2004-10: Fifty lakh jobs lost?

The Times of India, Aug 23, 2015

5 million jobs lost during high-growth years, says study

As many as five million jobs were lost between 2004-05 and 2009-10 — paradoxically during the time when India's economy grew at a fast clip — an Assocham study said.

This has put a question mark on whether economic expansion should be linked to job creation, according to the study.

Moreover, it observed that over-emphasis on services and neglect of the manufacturing sector are mainly responsible for this "jobless growth" phenomenon. Even as about 13 million youth are entering labour force every year, the gap between employment and growth widened during the period, the study noted.

"The Indian economy went through a period of jobless growth when five million jobs were lost between 2004-05 and 2009-10 while the economy was growing at an impressive rate," Assocham said.

Quoting Census data, it said the number of people seeking jobs grew annually at 2.23 per cent between 2001 and 2011, but growth in actual employment during the same period was only 1.4 per cent.

"This large workforce needs to be productively engaged to avoid socio-economic conflicts," Assocham secretary general D S Rawat said.

The changing demographic patterns, he said, suggest that today's youth is better educated, probably more skilled than the previous generation and highly aspirational.

"In a service-driven economy, which contributed 67.3 per cent (at constant price) to GDP but employed only 27 per cent of total workforce in 2013-14, enough jobs will not be created to absorb the burgeoning workforce," Assocham added.

Experts argue that the growth of manufacturing will be key for growth in income and employment for multiple reasons. For every job created in the manufacturing sector, three additional jobs are created in related activities.

In 2013-14, manufacturing contributed 15 per cent to GDP and employed about the same percentage of total workforce, a sign that the sector has a better labour absorption compared with services.

From 2011 to 2016 new jobs declined from 9 lakh to 1.35 lakh

PTI |7 million jobs can disappear by 2050, says a study, Oct 16, 2016

- As many as 550 jobs have disappeared every day in last four year, a study has claimed

- India created only 1.35 lakh jobs in 2015 in comparison to 4.19 lakh in 2013 and 9 lakh in 2011

- The data clearly points to the fact that job creation in India is successively slowing down

As many as 550 jobs have disappeared every day in last four years and if this trend continues, employment would shrink by 7 million by 2050 in the country, a study has claimed.

Farmers, petty retail vendors, contract labourers and construction workers are the most vulnerable sections facing never before livelihood threats in India today, the study by Delhi-based civil society group PRAHAR has said.

As per the data released by Labour Bureau early 2016, India created only 1.35 lakh jobs in 2015 in comparison to 4.19 lakh in 2013 and 9 lakh in 2011, the group said in a statement.

"A deeper analysis of the data reveals a rather scary picture. Instead of growing, livelihoods are being lost in India on a daily basis. As many as 550 jobs are lost in India every day (in last four year as per Labour Bureau data) which means that by 2050, jobs in India would have got reduced by 7 million, while population would have grown by 600 million," the statement said.

The data clearly points to the fact that job creation in India is successively slowing down, which is very alarming, it pointed out.

"This (rise in unemployment) is because sectors which are the largest contributor of jobs are worst-affected. Agriculture contributes to 50 per cent of employment in India followed by SME sector which employs 40 per cent of the workforce of the country," the statement said.

The organised sector actually only contributes a minuscule less than 1 percentage of employment in India. India has only about 30 million jobs in the organised sector and nearly 440 million in the unorganised sector.

According to the World Bank data, percentage of employment in agriculture out of total employment in India has come down to 50 per cent in 2013 from 60 per cent in 1994.

It said that the labour intensity of small and medium enterprises is four times higher than that of large firms.

It further said that the multinationals are particularly capitalistic a fact vindicated during investment commitments of USD 225 million made for the next five years during the Make in India Week in February 2016.

However, what went unnoticed is that these investments would translate into creation of only 6 million jobs, it said.

"India needs to go back to the basics and protect sectors like farming, unorganised retail, micro and small enterprises which contribute to 99 per cent of current livelihoods in the country. These sectors need support from the Government not regulation. India needs smart villages and not smart cities in the 21st century," it added.

Periods and regions of good employment growth

2001-11: urban employment exceeds rural

For 1st time, urban areas pip villages in job creation

Subodh Varma TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

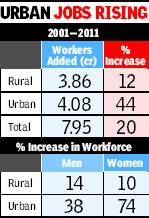

A fascinating, but worrying, picture of the way common Indians are earning their living emerges from recently released Census 2011 data. Urban areas have emerged as huge magnets for jobs, for the first time beating the rural hinterland in job creation in the past decade. Simultaneously, there is a rising dependence on short-term jobs, both in rural and urban areas, as regular full-term jobs fade away. The data also reveals huge differences in the kind of jobs men and women are getting. Clearly, India is going through a churning process, which will have far reaching effects on living standards, job related migration and gender relations.

More than half of the total 8 crore jobs created between 2001 and 2011 were located in urban areas, although the population staying in cities and towns is just a third of the total. This is a direct result of migration of people from unproductive farming in search of better prospects, supplemented by more areas getting defined as urban.

In the urban areas, women’s employment has seen a massive jump of over 74% since 2001, compared to just 38% for men. Women’s employment increased by over 1.2 crore in urban areas.

But the most significant feature is the creeping marginalization of jobs. Over 3 crore of the new jobs created in the past decade – 40% of the total – have been designated as ‘marginal’. This means that people work in these jobs for less than six months. A quarter of India’s 40-crore workforce is now subsisting on such marginal work.

While cultivation as the main occupation has declined by about 8% over the past decade, among marginal workers the picture is totally different. It has increased by 35% among male marginal workers, but declined by 20% among women. Seen in the context of the huge decline in main cultivators, it appears that men have been forced to work part time in their fields and part time either in others’ as agricultural labour or even in other kinds of work.

There appears to be a distinct shift towards what the census still persists in calling ‘other’ work – industry and services. And the vast bulk of these jobs are being created in cities and towns. Main workers in ‘other’ work jumped by 38% over the past decade compared to a measly 10% increase in rural areas. This is not surprising as most industries and service related jobs are located in urban or periurban areas (areas adjoining urban areas). Even here, the share of short- term workers in these ‘other’ jobs increased by a jaw dropping 84%.

2011-12: small towns as hubs

The Times of India May 24 2015

Subodh Varma

Small towns beat metros as job hubs

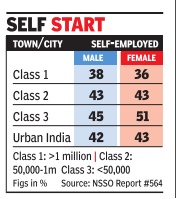

Smaller towns are surging ahead as hubs of jobs and entrepreneurial activity, beating larger cities and even metropolises. While industrial activity declines in big cities, smaller cities and towns are picking up the slack, often displaying a preference for manufacturing at the cost of the services sector. Construction is booming and related jobs are more to be found in smaller towns.These are some of the facets of urban India revealed in a recent NSSO report on employment in cities. Among Class III towns those with a population less than 50,000 nearly 45% of male workers and over 50% of female workers were self-employed. In big cities with a million-plus population, the proportion of self-employed was about 36-38% for both men and women. Self-employed includes very small industrial or service sector units as well as shops.

Salaried jobs up

Compared to 2004-05, in 2011-12, the latest year for which this data is available through NSSO survey reports, there has been a general decline in self-employment while regular wage or salaried employment has gone up in all sizes of cities and towns.

In big million-plus cities, a high 55% of men and 58% of women in the workforce were getting a regular wage or salary . This percentage was below 50 a decade ago. Life is more uncertain and livelihood a work in progress, as one descends the ladder of towncity size. Because, one step down, in Class II cities with population less than one million but more than 50,000, the proportion of salaried workers is 41-43% for both men and women. In towns with less than 50,000 population, the proportion of salaried sinks to just 34% for men and 27% for women.

More jobs for women in small towns

But smaller towns and cities are perhaps going through an evolution that big cities saw a couple of decades earlier. Between 2004-05 and 2011-12, male employment in the tertiary or services sector expanded in million-plus cities from 61 to 63% while industrial employment de clined from about 38 to 36%. But in Class III towns, service sector jobs declined from 53 to 51% while industrial jobs increased from 32 to 35%.For women, the changes were more drastic with industrial jobs declining from nearly 34% in big cities to 29 % but zooming up from 29 to 38 % in small towns.

The smaller the town, the more it is tied up with the rural economy , which provides jobs to an increasing proportion even from urban areas. In towns below 50,000 population, a quarter of the female workforce and about 14% of male workers still worked in agricultural operations, which are physically close and tightly intertwined with the small-town economy . In million-plus cities, just 2% of the female workforce and less than 1% of male workers were involved in agriculture, mostly at the geographical fringes of the metropolises.

The decline of female employment opportunities in these years has led to an increase in urban women working in agricultural activities with their proportion rising from about 18% to 25% in Class III towns. Male participation in agriculture in urban areas has remained stagnant or declined.

Casual labour by men appears to have increased in smaller towns although it has declined for women. In small towns, share of men doing casual work was 19% in 200405 which inched up to 21% in 201112 although the corresponding share of women in casual work dipped from 23 to 22%.

2014: Employment rate of Indians hits record high

The Times of India, Nov 02 2015

Kounteya Sinha

Employment rate of Indians in Britain hits record high

The employment rate of the Indian community reached a record high at 71.6% in Britain in 2014 . The employment rate of Pakistanis and Bangladeshis jointly was only 51%, while that of the Chinese was 56%.

This means 784,000 Indian people were at work in Britain, an increase of 32,000 from the previous year and 238,000 more since 2005. Of these, over 100,000 people from the Indian community run their own businesses in the UK.

As against Indians, only 560,000 Pakistanis and Bang ladeshis held jobs in 2014, while the number was as low as 135,000 among Britain's Chinese community .

The rate at which Indians in the UK are getting jobs has left all other ethnic minority groups behind. In 2006, 600,000 Indians aged 16 years and over were employed.

The number increased to 638,000 in 2008, 671,000 in 2009 and 692,000 in 2010. In 2011, it was 712,000 which rose to 752,000 in 2013.

Indians in UK were also recently found to be the most prosperous among all minority groups.

Employability of Indians

2015-2016

Gupta, Employability of Indians up in last 4 years: Study, Nov 08 2016 : The Times of India

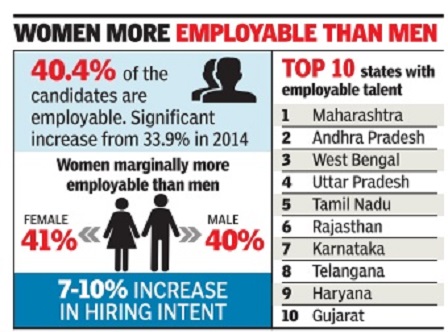

Employability of Indians has slowly increased over the past four years and nearly 40.4% of students are now employable, up from 33.9% in 2014, the India Skills report 2017 has shown. According to the survey launched in 2014, employability stood at 37.2% in 2015 and rose to 38.1% in 2016.

Women were found to be marginally more employable than men in the 2017 survey whose findings will be released on Thursday . Nearly 41% of women were found to be employable, slightly higher than the 40% in males.

Maharashtra has the highest number of employable people followed by Andhra Pradesh, UP, West Bengal and Tamil Nadu.Bengaluru and Pune were the most preferred destinations for employment.

The survey is a collaborative effort of People Strong, Confederation of Indian Industry , LinkedIn, UNDP, Wheebox, Association of Indian Universities and the All India Council for Technical Education.

Employability tests were conducted between July 15 and October 30 in 29 states and seven Union territories and covered 3,000 campuses. It assessed about 5.2 lakh candidates on seven parameters, which included English, mathematical aptitude, critical thinking, learning agility , interpersonal skills, adaptability and domain skills.

Students from across a wide range of subjects, such as engineering, business administration, humanities and those from ITIs, took the tests.Engineering and MBA students were found to be most employable and students from polytechnics the least.“As the economy grows, there is a thrust on skills and, hence, employability is increasing. But there is a long way to go to raise the level,“ said Nirmal Singh, CEO of Wheebox, a talent assessment company which conducted the tests.

The survey showed that hiring sentiment remained steady with employers across sectors expecting an average increase of about 7-10% from last year. The survey covered over 125 employers spread across 11 major sectors, like manufacturing, ITES and IT, to get an idea of the demand for jobs and potential hiring intent for the coming year.

Wheebox's Singh said while the hiring intent would stay robust in 2017, it would be slower than last year's 14%. Engineers will be the most sought after.

High growth and job creation

LIVELIHOODS - High growth not enough for job creation

Atul Thakur The Times of India Sep 23 2014

Rapid increase in the GDP has not ensured that jobs are created just as fast. The quality of employment also remains a matter of concern

After years of low growth, the In dian economy is showing signs of recovery . But the big ques tion remains -will a return to high growth, if that happens, also mean rapid job creation?

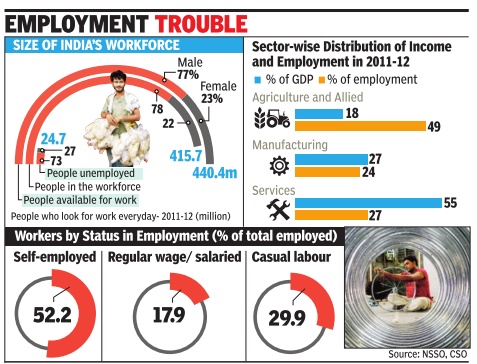

Data suggests this does not follow automatically. Between 2004-05 and 2009-10, a period that saw three successive years of 9%-plus growth, data from the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) showed virtually no growth in employment. Jobless growth is a real threat. The NSSO survey indicates that India's labour force was between 440 million to 484 million in 2011-12. The lower number indicates people who looked for work every day, while the higher points to those who joined the workforce at some point in the year. The data shows that 416 million of the 440 million who looked for work on a daily basis were employed at the time of the sur vey, meaning about 25 million remained unemployed.

Even what employment is available tends to be of low quality. In 2011-12, NSSO data shows, only 18% of working people had regular wagesalary employment.Roughly 30% were casual labourers, dependent on daily or periodic renewal of job opportunities. The remaining 52% were self-employed. Most of them were in agriculture, working as helpers in familyowned businesses without salary .

Much of the workforce in advanced economies is employed on regular wage salary. In the US, UK, Japan and Germany , roughly 90% of the workforce are regular wagesalary earners. World Bank's World Development Report, 2014, shows that the average proportion of people with regular wage employment in India's workforce was 17% during 2001-10. This was only 2% higher than in the previous decade.Evidently , the benefits of high GDP growth haven't helped most workers.

Estimates on employment in organised and unorganised sectors confirm India's dire situation. The unorganised workers social security act, 2008, defines unorganised workers as those who are home-based, self-employed or are wage workers in the organised sector not covered under labour welfare acts. This category is estimated to constitute more than 90% of the workforce.

As for the self-employed, there's reason to believe this category has a large element of disguised unemployment. This becomes clearer when we see the sector-wise employment and income patterns. In 2011-12, agri culture, forestry and fishing contributed 18% to overall GDP but employed 49% of the workforce. The secondary sector ¬ manufacturing, mining, electricity and construction ¬ had a share of 27% in GDP and 24% in employment. Services, dubbed engine of India's GDP growth, accounted for 55% of the total national output but employed a meagre 27% of the workforce. . Much of the `employment' in agricul ture -or even in small self-owned shops -is as a fallback in a distress situation in which jobs are not available and the absence of a social security net means the poor cannot afford to be unemployed. Rural job guarantee scheme NREGA , signalled a recognition of this reality and sought to provide relief.

However, it has not been able to provide work for the promised 100 days a year to most households. In 2013. 14, only 9% of households who sought it could get work for 100 days. The average was 43 days per household. The scheme focuses on unskilled work. The problem of skill development enabling labour migration to services remains inadequately addressed. India's employment crisis is marred by social issues which don't allow women to join the labour force. While over 55% of men was available in the labour force at some time in the year, according to NSSO, only 22% of women were available for work. That women are often paid lower wages than men for doing the same work does not help gender parity, either.

Job creation and the states

Poorer states take the lead in creating jobs

Subodh Varma | TIMES INSIGHT GROUP 2013/06/17

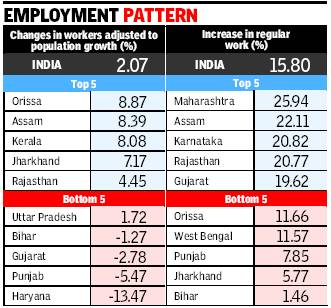

Most of the poorer, less industrialized states like Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Bihar appear to have done well in increasing their work force in the past decade according to recently released Census 2011 data. Surprisingly, richer or more urbanized states like Punjab, Haryana and Kerala have lagged far behind in job creation. But if you take away natural population growth, the picture changes dramatically.

It becomes clear that the workforce increase in the poorer states is mainly because of their higher than national aver- population growth. But again surprisingly, the richer states still remain at the bottom of job creation rankings. In terms of increase in total workers’ population, the top five states were Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan, Assam and Bihar, counting only major states, that is, those with over 2 crore population. The increase in their respective workforce was considerably higher than the national average. The states with the least increase over the past decade were Haryana, Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Gujarat.

UP, Bihar: least job creation

Since there is a natural growth in population, these figures do not give a correct picture of the changes in job opportunities in these states. Arough idea of what is the actual change in employment can be had by deducting the growth in population from the growth in workers. This reveals that Orissa, Assam, Kerala, Jharkhand and Rajasthan are the top five states in terms of job creation during 2001 and 2011.

While Orissa, Assam and Kerala appear to benefit from a much reduced population growth rate, Jharkhand and Rajasthan seem to have genuinely boosted jobs creation. After adjusting for population growth, the states with least job creation were Haryana, Punjab, Gujarat, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The latter two were hamstrung by still high population growth rates but the other three are laggards in job creation, reflecting stagnation and increased mechanization. These three also showed an absolute decline in the female workforce over 2001 and 2011. Census counts short term workers – those doing less than six months' work in a year – separately.

A look at how the cookie crumbles across the states in terms of short term work and longer term, more regular work throws up some bizarre results. While Maharashtra, Assam, Karnataka, Rajasthan and Gujarat created the most long term workers (‘main workers’), Bihar, Jharkhand, Punjab, West Bengal and Orissa added the least. On the other hand, short term, marginal workers increased by a jaw dropping 93% in Bihar, followed by Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Orissa, UP. This is the fragile nature of job growth in states which may appear to be adding jobs in the past decade.

The rural-urban divide is starkly shown up in job creation, reflecting the doldrums that Indian agriculture is in. Across India, rural job growth was just 13% compared to 44% in urban areas. Some of the most agriculturally advanced states like Haryana and Punjab showed a decline in rural workforce while others like Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat had very small increases. The situation flips for urban areas where most states showed a healthy increase in the workforce. But Punjab, along with the two most urbanized states in the country, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, still remained at the bottom.

Employment in North East India

Job scenario in most NE states alarming

More Workers Join Labour Force Than Jobs Are Created In Mizoram, Meghalaya, Arunachal

Subodh Varma TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

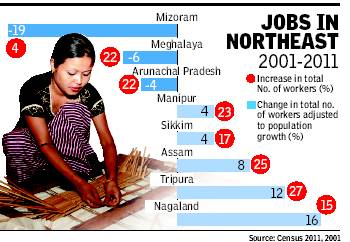

Made up of eight states and accounting for about 4% of India’s population, the northeast is better known for its separatist movements and incendiary ethnic conflicts. It has 25 Lok Sabha members, 14 of them from Assam, and so, does not draw serious attention from political parties involved in the national sweepstakes. The region receives huge funds from the central government that prop up the local economies. But simmering under the surface is a question that haunts everybody — what about jobs?

Census 2011 data released this year has some strange and disturbing trends on jobs in the northeast. If states were to be ranked by growth in jobs between 2001 and 2011, Tripura and Assam would figure among the top five states with 27% and 26% increases in total number of workers, respectively. But on the flip side, the growth in workers was just 4% in a decade in Mizoram – the lowest among all states. Three states — Mizoram, Nagaland and Sikkim — were below the national average of 20% growth in workers between the two censuses.

These growth rates may be deceptive because population has been growing in the same period. A better idea of how many jobs are being created can be had by deducting population growth rate from the increase in workers. This reveals a much more serious situation in the northeast.

Three states — Meghalaya, Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh — show a decline in total workers. This means that more workers are joining the labour force than jobs are being created. Among these, Mizoram is facing a shocking crisis with a decline of over 19%. One factor could be that Mizoram is now an urbanmajority state – over 52% of its population stays in urban areas. So the buffer of agriculture is absent. Seen in the context of the fact that Mizoram has one of the highest literacy rates at 91%, this must be food for thought for policy makers both in Aizawl and New Delhi.

In two other states, Sikkim and Manipur, the adjusted growth rate plummets down to around just 4% in a decade. Tripura with 12% and Assam with over 8% perform creditably in comparison to the other states. Nagaland has the most bizarre situation – since the total population of the state has declined between 2001 and 2011 the two censuses, it shows a rise of nearly 15% in its workforce, adjusted to population.

Lack of growth in non-farm employment in most states, and the difficult hilly terrain, about 70% of which is under forest cover, are two key reasons why employment is stagnating in the northeast, says Bhupen Sarmah, director of the O K Das Institute, a Guwahati-based research institute. “It is an illusion to think that development will take place merely on the basis of injection of funds from the central government. The northeast receives a huge amount of this largesse but look what is the result,” Sarmah points out.

Sarmah may have a point, although it is also true that a lot of the largesse remains on paper. According to the ministry of development of north eastern region, a special non-lapsable fund created for financing projects in the northeast approved projects worth Rs 12,716 crore between 1998 and 2012. Sounds great, but there’s a catch — only about Rs 9,231 crore were actually released and state governments submitted utilization certificates for only Rs 5,641 crore. A Lok Sabha question recently revealed that about Rs 2,000 crore remains unspent from this fund every year between 2008-09 and 2010-11.

Another example is the national job guarantee scheme (MGNREGS) that promises 100 days of employment to anybody who demands. In some states it has become a mainstay of economic support, like in Mizoram with average 73 days of work provided and Tripura (87 days). The national average is just 44 days per household.

But some other states in the northeastern region are drastically lagging — Assam (25 days), Nagaland (35) and Manipur (37).

Eligibility for employment as lecturer

August 11, 2008

SC solves degree puzzle

Degree-holder in Pol Sc eligible to be a lecturer in Public Admn and vice versa

Dhananjay Mahapatra | TNN

FROM THE ARCHIVES OF ‘‘THE TIMES OF INDIA’’: 2008

The Supreme Court has ruled that a degree holder in political science is eligible to become a lecturer in public administration and vice versa.

This important ruling came from a Bench comprising Justices Altamas Kabir and Markandey Katju, which demolished a wedge driven by the apex court in 2001 between the two subjects, treating them as distinct and separate. Dr Rajbir Singh Dalal, who had a masters degree and PhD in political science, was appointed as reader in public administration by the Chaudhary Devi Lal University, Sirsa.

It was challenged in the Punjab and Haryana High Court by a person citing a 2001 judgment of the apex court in Bhanu Prasad Panda vs Sambalpur University, in which it was held that public administration and political science were two separate disciplines. The HC, relying on the SC judgment, cancelled Dalal’s appointment. To arrive at the conclusion, the HC further relied on Regulation 2 of the University Grants Commission (UGC) Rules which state that for appointment to the post of a reader, the candidate must have to be qualified in the relevant subject.

With two sets of disadvantages loaded against him, Dalal moved the apex court. Both Justices Kabir and Katju arrived at the same conclusion, using different routes, to rule that the 2001 judgment was a mere assertion and could not be taken as a precedent. Aided by the support of the UGC which said that the two subjects were inter-linked, Justice Kabir said that in 2001, the apex court did not have the benefit of the UGC’s view and had arrived at the conclusion on the basis of a personal understanding of public administration and political science.

Once the expert bodies had indicated that Dalal, who held a PG degree in political science, was rightly appointed to the post of reader, it was normally not for the courts to question such opinion, unless it had specialised knowledge of the subject.

The 2001 decision of the apex court did not reflect the reason for which the two subjects were not treated to be interlinked, he said and agreed with Justice Katju that expert opinion on such issues should get primacy from the courts.

Double income households

Census busts urban myth, finds Bharat has more DINKs

Subodh Varma

The Times of India Aug 31 2014

Rural Figure Is 42% Compared To 22% In Cities

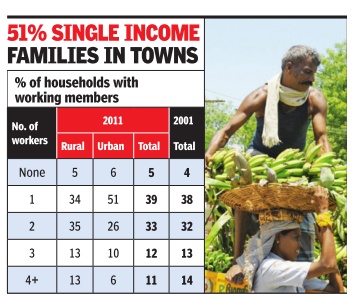

With all the buzz around double-in come power couples, it is easy to believe that more and more urban families have given up the sole breadwinner model of the past. But that would be a mistake, as just released Census 2011 data shows.

An overwhelming 51% of urban households live on the income of a single earner, while double-income families are a distant 26%. In rural areas, the situation is quite different. While 34% of families have a single worker, double-worker families are slightly more at 35%.

In fact, the double-income-no-kids (DINK) lifestyle celebrated as a cosmopolitan aspiration is prevalent in nearly 42% of two-member rural families compared to just 22% of similar urban families.

If you combine the rural and urban figures, here is what emerges for the India picture: 39% of households sustain themselves on the income of a single working member while 33% depend on two workers. This is not too different from a decade ago, when Census 2001 had revealed that 38% of households had a single breadwinner while 32% had two working members.

Perhaps this is because rural families are bigger and so more members are able to work? Not true. In urban ar eas, nearly three quarters of families have 3-6 members. In rural areas, 66% are in this range. Clearly , this size is the most predominant one in both rural and urban areas. About 17% of families in rural areas have 7-10 members compared to nearly 13% in urban areas.

Two inter-related factors drive rural families towards multiple persons going out to work. The primary reason is economic necessity . Average rural income is estimated at a meagre Rs 6,307 per month for a typical household by the most recent consumer expenditure survey in 2011-12 done by the National Sample Survey Organization. In inflationadjusted terms, rural incomes have increased by a paltry 2% per year. So families need to supplement their incomes. In urban areas, average household income is Rs 11,394 for a typical sized household, and it has increased by a slightly better 3% annually . Alongside economic necessity, the second factor that tilts the balance for multiple worker families in rural areas is women workers. Census 2011 data had earlier shown that the share of working women in rural areas was 35% compared to just 21% in urban areas. This is despite the drastic drop in women’s employment in the past few years. For a variety of cultural, economic and security reasons, most women in urban families are not gainfully employed outside their homes, causing dependence on a single income.

In rural areas, efforts by families to supplement their incomes do not meet with much success because about a third of multiple workers are getting jobs for only up to six months. In urban areas, the proportion of such marginal workers is much lower at 12% to 20%. Marginal workers usually get irregular work for very low wages.

Unorganized Sector

Real estate biggest job creator: Report

PCOs Largest Enterprise In Unorganized Sector

New Delhi: If you feel the number of PCO booths and real estate agents in your colony seems to increasing every day, you are right.

Delhi government’s report on service sector enterprises in Delhi that is based on the National Sample Survey 63rd Round Survey (July 2006-June 2007) shows that at 62,111 (18.40%) enterprises, communications — read PCO booths — comprise the largest number of unorganised sector enterprises in the city.

These include both own account enterprises (businesses where only family members work) and establishments (that have salaried employees). And the largest number of jobs (1,04,227, which comes to about 16.20%) are provided by real estate, renting etc. The report says that of the 2.39 lakh enterprises in the city, 12.64% (30255) were dhabas etc, 17.23% (41246) were real estate, renting and business activities, 19.88% (47584) were in transport activities, 18.40% (44054) were in communication, 16.58% (39696) were in other community, social and personal service activities.

About 17.62% (1.13 lakh) employees worked in dhabas, real estate employed 16.20% (1.04 lakh), 12.30% (0.79 lakh) were employed in education (private tutors etc) and 10.15% (0.65 lakh) were employed in health and social work activities.

Predictably, a big chunk of the employment in the unorganised sector comes from “other community, social and personal service activities” which includes maids, dhobis, dhaba workers etc. They comprise 13.43% of the total number of employees (6.44 lakh) in the sector. The gross value of all these enterprises, according to the report, comes to Rs 6,879 crore.

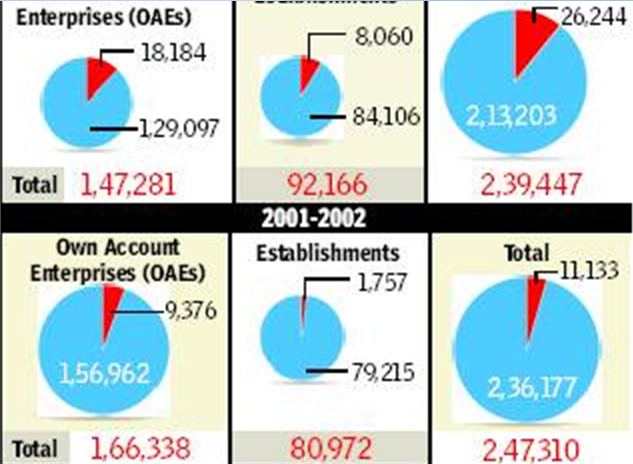

A comparison of the absolute figures however shows a decline in the number of OAEs in the city and an almost proportionate rise in the number of establishments.

Which officials say could actually signify expansion of the already existing smaller units rather than any new one actually opening. In 2001-02, the number of OAEs stood at 16,6338, while in 2006-07 it was 14,7281. On the other hand, 10 years back the number of establishments was 80,972, while in 2006-07 it stood at 92166. Social realities are reflected in the ownership figures which show that just 10% businesses are woman-owned, 9.88% owned by scheduled castes and 73.11% are owned by other backward castes.

toireporter@timesgroup.com

Vacations

The Times of India, Dec 13 2016

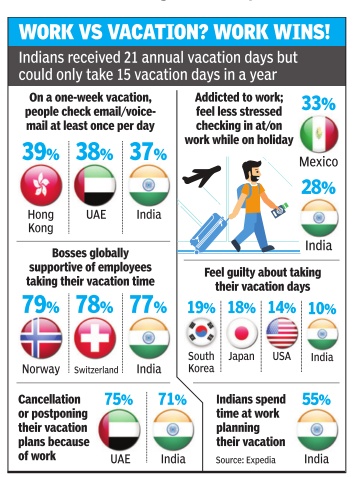

Indians world's fourth-most holiday-starved

Blame it on a busy family life or a bid to impress the boss: Indians are the fourth-most vacation-deprived people in the world, according to a study by an online portal. Around 63% of Indians surveyed said they took fewer days off than they were entitled to. On an average, Indians are entitled to 21 days of annual vacation but take just 15.

Only Spain and the UAE (both 68%), Malaysia (67%) and South Korea (64%) fared worse than India.

Incidentally, 95% of Indians said they believed vacations played a key role in creating work-life balance and re-energised people, which ensured better performance at work.