Election Commission of India

(→Election commissioners, selection of) |

(→History) |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by one user not shown) | |||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

See [[examples]] and a tutorial.</div> | See [[examples]] and a tutorial.</div> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | [[ | + | |

| − | [[Category:Government | | + | |

| − | [[Category: Law,Constitution,Judiciary| | + | |

| − | [[Category:Name| | + | |

| + | =History= | ||

| + | ==CECs: TN Seshan, before and after== | ||

| + | [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/why-india-is-missing-tn-seshan/articleshow/95719282.cms Nov 24, 2022: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: What Seshan would have pushed back against.jpg|What Seshan would have pushed back against <br/> From: [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/why-india-is-missing-tn-seshan/articleshow/95719282.cms Nov 24, 2022: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: The Seshan handbook.jpg|The Seshan handbook <br/> From: [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/why-india-is-missing-tn-seshan/articleshow/95719282.cms Nov 24, 2022: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '' He cleaned up the mess that characterised Indian elections by ensuring that everyone adhered to the rulebook. He brooked no interference from any political party, something that seems impossible today '' | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | He was the man who made Indians aware of the Election Commission. TN Seshan, appointed chief election commissioner in 1990, took a slew of decisions to make the commission an independent panel: Elections would not go forward till fair conditions were established, it was the Election Commission, not state governments that would determine the deployment of security forces to ensure honest polling, elections would be staggered so that security forces could move from one section of the state after another, combating booth capturing. He even wanted voter ID cards to check impersonation, something that the Supreme Court thought was an unwarranted excess. By the time his term ended, Seshan was a public hero. Indian elections were no longer as chaotic and corrupt as they once were – and voter ID cards are now the norm. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Seshan made the Election Commission a force to be reckoned with. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “That kind of person is needed and not a political person. Character of a man is important to make independent decisions and not get influenced. We need such a person and how to get such a person is the question,” the Supreme Court observed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | TN Seshan is the gold standard on what it takes to conduct free and fair elections and it is not the first time that he has been remembered as a person who changed the face of elections in the country.

| ||

| + | Before the 2018 Madhya Pradesh Assembly elections, the Supreme Court said that the credibility that Seshan had given the Election Commission would be tested in the conduct of the elections. | ||

| + |

Similarly, in 2021, the Calcutta high court reminded the Commission that its “onerous” responsibility does not end with “issuing circulars” and “holding meetings” and that the judiciary would step in and “act like TN Seshan” if the poll panel failed to enforce Covid-safety protocols during electioneering in West Bengal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' What needs to change? ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | First is the issue of the government choosing serving bureaucrats as chief election commissioner (CEC) and election commissioners (ECs). | ||

| + | |||

| + | A five-judge Constitution bench of the top court, hearing a batch of petitions on keeping the Election Commission independent of political or executive interference, has raised questions on the system. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pointing out that Article 324 (2) mandates the framing of a law for selection and appointment of CEC/ECs, the bench said nothing had been done in the last seven decades. “This is how the silence of the Constitution is being exploited,” said the court. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Second is the tenure of CECs. According to the Constitution, the CEC has a maximum tenure of six years. Between 1950 and 1996, India had 10 CECs. However, in the 26 years after Seshan – the last CEC with a six-year tenure – we have had 15 CECs. Of these, six CECs were appointed between 2004 and 2015 and eight had been appointed by the present government in the last seven years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Justice KM Joseph, who heads the five-judge constitution bench hearing the petitions, said that all governments at the Centre were guilty of choosing CECs who would have short terms in office. | ||

| + | “It is a disturbing trend of picking and appointing a person who will never get a six-year tenure and will have a truncated period of service. Independence (of the poll panel) is completely destroyed and the CEC will never be able to do what they want to do. The situation is the same whether it is a UPA [United Progressive Alliance] or an NDA [National Democratic Alliance] government,” the bench observed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The court also pointed out that the process of selection and appointment for poll panels in many countries, including Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal, was more transparent, and that those countries had laws to ensure transparency. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''' How can this situation be improved? '''

| ||

| + | The petitions before the court challenge the present appointment process and claim that appointments are made on the whims and fancies of the executive. The petitions ask for the creation of an independent collegium or selection committee for future appointments of CEC and two other ECs. | ||

| + |

Their argument: unlike the appointments of the CBI director or Lokpal, where the leader of the Opposition and judiciary have a say, the Centre unilaterally appoints the members of the Election Commission. | ||

| + |

Significantly, the Law Commission had recommended a change in the existing procedure and said in its 2015 report that the appointment of all the election commissioners, including the CEC, should be made by the President in consultation with a three-member collegium or selection committee consisting of the Prime Minister, the leader of the Opposition of the Lok Sabha (or the leader of the largest opposition party in the Lok Sabha) and the Chief Justice of India. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' What Seshan managed '''

| ||

| + | TN Seshan, who served as the 10th CEC from December 12, 1990, till December 11, 1996, showed politicians the real power of the Election Commission.

| ||

| + | During his term, Seshan built up the institution of the CEC and established practices that continue to this day.

| ||

| + | Seshan brooked no political interference and he brought back faith in the Indian electoral system at a time when Indian elections were synonymous with booth rigging and misuse of government machinery. | ||

| + |

It helped that the prime minister for much of his term was PV Narasimha Rao, who headed a minority government and was not in a position to throw around the power of the executive. Sure, the Rao government did try to stymie Seshan by using a little-known clause of the law governing the EC and appointing two additional commissioners, but that did not lessen what Seshan strived for.

He had strict commandments — no bribing or intimidating voters, no distribution of liquor during the elections, no use of official machinery for campaigning, no appealing to voters' caste or communal feelings, no use of religious places for campaigns and no use of loudspeakers without prior written permission. He also enforced the Model Code of Conduct, strictly monitored limits on poll expenses, and cracked down on several malpractices like wall graffiti. | ||

| + |

His iron-clad instructions ended up offending politicians but endeared him to citizens. Most importantly, he demonstrated that one determined individual could fully articulate the innate, albeit hidden and unused, strength of an institution to benefit democracy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Controversies EC has faced== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Once a gold standard institution, the Election Commission’s responses – or lack of any – in some instances have been questioned recently: | ||

| + | |||

| + | * In the lead-up to the 2019 general elections, the Opposition accused the BJP of contravening EC rules by appropriating credit for the heroic actions of the armed forces in its campaign and using PM Modi’s TV broadcast on an anti-satellite missile test for political gain | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Questions were raised about the timing of the investigation by central agencies/departments of family members of election commissioner Ashok Lavasa as they coincided with his dissenting notes against the EC’s weak response to allegations of model code violations by the BJP and its leadership during the 2019 elections. Instead of going on to take over as CEC, Lavasa resigned from the EC in 2020 | ||

| + | |||

| + | =CECs: tenures of= | ||

| + | ==2000-24== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/article-share?article=24_11_2022_013_004_cap_TOI Dhananjay Mahapatra, Nov 24, 2022: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | New Delhi : If appointment of as many as 15 chief election commissioners during the last 26 years was a “disturbing trend” capable of destroying the independence of the poll panel, then the Supreme Court must take a glance at the appointment of as many as 22 Chief Justice of India in the last 24 years, which contrasts with 28 CJIs appointed in 48 years since 1950 when the apex court came into existence. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Since 1998, the CJI-led collegium, also comprising the four most senior SC judges, has appointed 111 SC judges to the SC. From them, Justice R C Lahoti was the first to become CJI in 2004 and since then 15 more have reached the top judicial post. While recommending candidates names to the government for appointment as SC judge, the CJI andfour most senior SC judges know what each one’s tenure in the SC would be and whether, and for what period, would he/she, if at all, become CJI. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Since 2000, there have been 22 CJIs, many whose tenures could be counted in days – Justice G B Patnaik (40 days), Justice S Rajendra Babu (30 days) and Justice U U Lalit (74 days). Others with short tenures were Justices Altamas Kabir and P Sathasivam (both little over nine months as CJI), J S Khehar (nearly eightmonths), and R M Lodha (five months). What did the CJI-led collegium think in selecting them as SC judges who would have short tenures as CJIs that would be insufficient to plan reforms in the judiciary, where pendency has doubled in the last two decades. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Interestingly, Justice Joseph led 5-judge bench on Tuesday observed, “appointment of members of the EC on the whims of executive violates the very foundation on which it was created, thus making the commission a branch of executive. ” Will the presence of CJI in a selection panel for appointments of EC/CEC help merit and infuse transparency? | ||

| + | |||

| + |

If that is so, why did a constitution bench of SC quash the National Judicial Appointment Commission, which was set up by a law unanimously enacted by Parliament? Even before NJAC, the working of theCJI-led collegium system had faced constant criticism for its opaqueness and nepotism. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Distinguished woman SC judge, Ruma Pal, had said the collegium operates on “you scratch my back and I scratch yours” basis. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

In the 2015 judgment quashing NJAC, SC had quoted Justice Pal as saying “Consensus within the collegium is sometimes resolved through a trade-off resulting in dubious appointments with disastrous consequences for the litigants and the credibility of the judicial system. Besides, institutional independence has also been compromised by growing sycophancy and lobbying within the system. ” Justice J Chelameswar had approved NJAC in his dissent. Justice Kurian Joseph acknowledged the opaqueness charge and said, “… the Collegium system lacks transparency, accountability and objectivity. ” | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Government|EELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIAELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA | ||

| + | ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|EELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIAELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA | ||

| + | ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Law,Constitution,Judiciary|EELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIAELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA | ||

| + | ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Name|ALPHABETELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIAELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA | ||

| + | ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA | ||

| + | ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA]] | ||

=Clashes of EC: with govt, within EC= | =Clashes of EC: with govt, within EC= | ||

| Line 59: | Line 147: | ||

“Now, all this army cannot be set up as a machinery independent of the government. It is not possible nor advisable to have a kingdom within a kingdom, so that election matters could be left to an entirely independent organ of the government. A machinery , so independent, cannot be allowed to sit as a kind of super-government to decide which government shall come to power. There will be great political danger if the Election Commission becomes such a political power in the country .“ | “Now, all this army cannot be set up as a machinery independent of the government. It is not possible nor advisable to have a kingdom within a kingdom, so that election matters could be left to an entirely independent organ of the government. A machinery , so independent, cannot be allowed to sit as a kind of super-government to decide which government shall come to power. There will be great political danger if the Election Commission becomes such a political power in the country .“ | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Model code violations= | ||

| + | ==2010-12== | ||

| + | [Bharti Jain, ‘Selective amnesia’: EC rebuts ex-CEC on its handling of hate speech, February 14, 2020: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | S Y Quraishi | ||

| + | led EC from 2010 to 2012, had in an opinion piece published in a daily on February 8, 2020, wondered why EC had stopped short of filing FIRs against Union minister Anurag Thakur and BJP MP Parvesh Verma under Representation of the People Act (RP Act) or Section 153 of IPC for hate speech despite finding them “guilty of offences deserving punishment” under Section 123 and 125 of RP Act. He, however, appreciated EC’s decision to drop the two from BJP’s list of star campaigners and temporarily bar them from campaigning. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In a reply sent to Quraishi on February 13, 2020 — a copy of which is with TOI — deputy election commissioner Sandeep Saxena put on record each of the model code violation proceedings undertaken during Quraishi’s own term. “It would be seen from the enclosed list that no action was taken by the then Commission during this period under Sections 123 and 125 of RP Act 1951/153 of IPC 1860,” he pointed out. | ||

| + | |||

| + | EC cites nine notices issued for polls during Quraishi’s term | ||

| + | |||

| + | EC cited the nine showcause notices issued for elections held between July 30, 2010 and June 10, 2012, coinciding with Quraishi’s term. While five notices were issued in 2012 UP poll, three in 2011 West Bengal poll, two in 2011 Tamil Nadu poll and one in 2010 Bihar poll. As per final outcome of these cases, advisories were issued in five, warning issued in two and remaining two cases closed. No directions were issued to lodge FIR in any of the cases. | ||

| + | |||

| + | No model code of conduct notices were issued during polls in Assam, Kerala, Puducherry, Goa, Manipur and Uttarakhand in the relevant period. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Citing the notice issued to then law minister Salman Khurshid for announcing 9% reservation for minorities within 27% OBC quota during UP poll, EC recalled that he was subsequently censured. Khurshid later reiterated the announcement, after which EC wrote to President seeking his intervention. Khurshid finally regretted his statements before EC, after which latter decided not to take further action. | ||

| + | |||

| + | EC also issued a notice to BSP’s S C Mishra in 2012 for his repeated references to Dalit-Brahmin political combination. Though Mishra did not reply, EC took a lenient view and merely hoped Mishra would be more careful in the future. Another notice went to former Union minister Beni Prasad Verma for making promises to Muslims, but after he regretted the same, EC did not press for further action. Even then Union minister Sri Prakash Jaiswal received an EC notice for threatening President’s rule in UP. Jaiswal claimed his statement was distorted and EC concluded there was no threat of intimidation of votes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In West Bengal poll in 2011, CPM’s Anil Basu had made obscene remarks against Trinamool chief Mamata Banerjee.EC only conveyed its severe displeasure and warned him to be more careful in the future. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Government|E | ||

| + | ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|E | ||

| + | ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Law,Constitution,Judiciary|E | ||

| + | ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Name|ALPHABET | ||

| + | ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA]] | ||

=Reforms, proposed and actual= | =Reforms, proposed and actual= | ||

| Line 99: | Line 218: | ||

[[Elections in India: opinion polls]] | [[Elections in India: opinion polls]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Government|EELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA | ||

| + | ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|EELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA | ||

| + | ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Law,Constitution,Judiciary|EELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA | ||

| + | ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Name|ALPHABETELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA | ||

| + | ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA]] | ||

Revision as of 19:39, 6 December 2022

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

History

CECs: TN Seshan, before and after

Nov 24, 2022: The Times of India

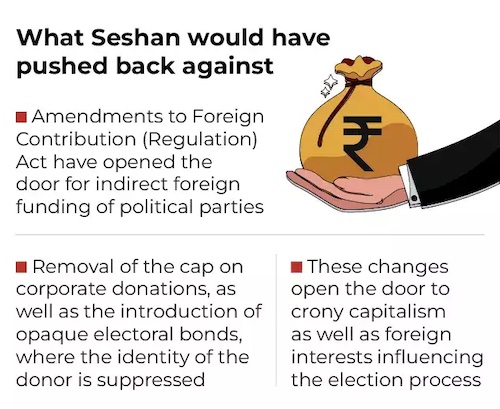

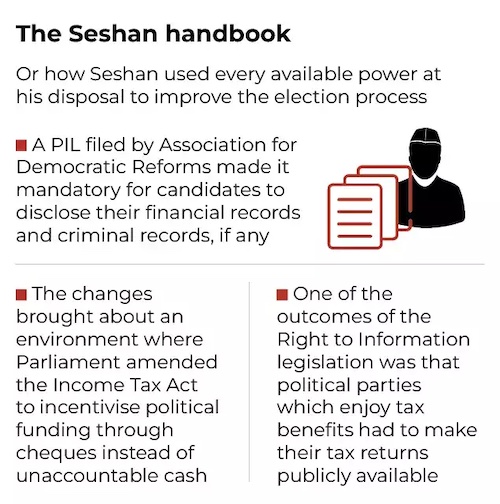

From: Nov 24, 2022: The Times of India

From: Nov 24, 2022: The Times of India

He cleaned up the mess that characterised Indian elections by ensuring that everyone adhered to the rulebook. He brooked no interference from any political party, something that seems impossible today

He was the man who made Indians aware of the Election Commission. TN Seshan, appointed chief election commissioner in 1990, took a slew of decisions to make the commission an independent panel: Elections would not go forward till fair conditions were established, it was the Election Commission, not state governments that would determine the deployment of security forces to ensure honest polling, elections would be staggered so that security forces could move from one section of the state after another, combating booth capturing. He even wanted voter ID cards to check impersonation, something that the Supreme Court thought was an unwarranted excess. By the time his term ended, Seshan was a public hero. Indian elections were no longer as chaotic and corrupt as they once were – and voter ID cards are now the norm.

Seshan made the Election Commission a force to be reckoned with.

“That kind of person is needed and not a political person. Character of a man is important to make independent decisions and not get influenced. We need such a person and how to get such a person is the question,” the Supreme Court observed.

TN Seshan is the gold standard on what it takes to conduct free and fair elections and it is not the first time that he has been remembered as a person who changed the face of elections in the country.

Before the 2018 Madhya Pradesh Assembly elections, the Supreme Court said that the credibility that Seshan had given the Election Commission would be tested in the conduct of the elections.

Similarly, in 2021, the Calcutta high court reminded the Commission that its “onerous” responsibility does not end with “issuing circulars” and “holding meetings” and that the judiciary would step in and “act like TN Seshan” if the poll panel failed to enforce Covid-safety protocols during electioneering in West Bengal.

What needs to change?

First is the issue of the government choosing serving bureaucrats as chief election commissioner (CEC) and election commissioners (ECs).

A five-judge Constitution bench of the top court, hearing a batch of petitions on keeping the Election Commission independent of political or executive interference, has raised questions on the system.

Pointing out that Article 324 (2) mandates the framing of a law for selection and appointment of CEC/ECs, the bench said nothing had been done in the last seven decades. “This is how the silence of the Constitution is being exploited,” said the court.

Second is the tenure of CECs. According to the Constitution, the CEC has a maximum tenure of six years. Between 1950 and 1996, India had 10 CECs. However, in the 26 years after Seshan – the last CEC with a six-year tenure – we have had 15 CECs. Of these, six CECs were appointed between 2004 and 2015 and eight had been appointed by the present government in the last seven years.

Justice KM Joseph, who heads the five-judge constitution bench hearing the petitions, said that all governments at the Centre were guilty of choosing CECs who would have short terms in office.

“It is a disturbing trend of picking and appointing a person who will never get a six-year tenure and will have a truncated period of service. Independence (of the poll panel) is completely destroyed and the CEC will never be able to do what they want to do. The situation is the same whether it is a UPA [United Progressive Alliance] or an NDA [National Democratic Alliance] government,” the bench observed.

The court also pointed out that the process of selection and appointment for poll panels in many countries, including Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal, was more transparent, and that those countries had laws to ensure transparency.

How can this situation be improved?

The petitions before the court challenge the present appointment process and claim that appointments are made on the whims and fancies of the executive. The petitions ask for the creation of an independent collegium or selection committee for future appointments of CEC and two other ECs.

Their argument: unlike the appointments of the CBI director or Lokpal, where the leader of the Opposition and judiciary have a say, the Centre unilaterally appoints the members of the Election Commission.

Significantly, the Law Commission had recommended a change in the existing procedure and said in its 2015 report that the appointment of all the election commissioners, including the CEC, should be made by the President in consultation with a three-member collegium or selection committee consisting of the Prime Minister, the leader of the Opposition of the Lok Sabha (or the leader of the largest opposition party in the Lok Sabha) and the Chief Justice of India.

What Seshan managed TN Seshan, who served as the 10th CEC from December 12, 1990, till December 11, 1996, showed politicians the real power of the Election Commission. During his term, Seshan built up the institution of the CEC and established practices that continue to this day. Seshan brooked no political interference and he brought back faith in the Indian electoral system at a time when Indian elections were synonymous with booth rigging and misuse of government machinery. It helped that the prime minister for much of his term was PV Narasimha Rao, who headed a minority government and was not in a position to throw around the power of the executive. Sure, the Rao government did try to stymie Seshan by using a little-known clause of the law governing the EC and appointing two additional commissioners, but that did not lessen what Seshan strived for. He had strict commandments — no bribing or intimidating voters, no distribution of liquor during the elections, no use of official machinery for campaigning, no appealing to voters' caste or communal feelings, no use of religious places for campaigns and no use of loudspeakers without prior written permission. He also enforced the Model Code of Conduct, strictly monitored limits on poll expenses, and cracked down on several malpractices like wall graffiti. His iron-clad instructions ended up offending politicians but endeared him to citizens. Most importantly, he demonstrated that one determined individual could fully articulate the innate, albeit hidden and unused, strength of an institution to benefit democracy.

Controversies EC has faced

Once a gold standard institution, the Election Commission’s responses – or lack of any – in some instances have been questioned recently:

- In the lead-up to the 2019 general elections, the Opposition accused the BJP of contravening EC rules by appropriating credit for the heroic actions of the armed forces in its campaign and using PM Modi’s TV broadcast on an anti-satellite missile test for political gain

- Questions were raised about the timing of the investigation by central agencies/departments of family members of election commissioner Ashok Lavasa as they coincided with his dissenting notes against the EC’s weak response to allegations of model code violations by the BJP and its leadership during the 2019 elections. Instead of going on to take over as CEC, Lavasa resigned from the EC in 2020

CECs: tenures of

2000-24

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Nov 24, 2022: The Times of India

New Delhi : If appointment of as many as 15 chief election commissioners during the last 26 years was a “disturbing trend” capable of destroying the independence of the poll panel, then the Supreme Court must take a glance at the appointment of as many as 22 Chief Justice of India in the last 24 years, which contrasts with 28 CJIs appointed in 48 years since 1950 when the apex court came into existence.

Since 1998, the CJI-led collegium, also comprising the four most senior SC judges, has appointed 111 SC judges to the SC. From them, Justice R C Lahoti was the first to become CJI in 2004 and since then 15 more have reached the top judicial post. While recommending candidates names to the government for appointment as SC judge, the CJI andfour most senior SC judges know what each one’s tenure in the SC would be and whether, and for what period, would he/she, if at all, become CJI.

Since 2000, there have been 22 CJIs, many whose tenures could be counted in days – Justice G B Patnaik (40 days), Justice S Rajendra Babu (30 days) and Justice U U Lalit (74 days). Others with short tenures were Justices Altamas Kabir and P Sathasivam (both little over nine months as CJI), J S Khehar (nearly eightmonths), and R M Lodha (five months). What did the CJI-led collegium think in selecting them as SC judges who would have short tenures as CJIs that would be insufficient to plan reforms in the judiciary, where pendency has doubled in the last two decades.

Interestingly, Justice Joseph led 5-judge bench on Tuesday observed, “appointment of members of the EC on the whims of executive violates the very foundation on which it was created, thus making the commission a branch of executive. ” Will the presence of CJI in a selection panel for appointments of EC/CEC help merit and infuse transparency?

If that is so, why did a constitution bench of SC quash the National Judicial Appointment Commission, which was set up by a law unanimously enacted by Parliament? Even before NJAC, the working of theCJI-led collegium system had faced constant criticism for its opaqueness and nepotism.

Distinguished woman SC judge, Ruma Pal, had said the collegium operates on “you scratch my back and I scratch yours” basis.

In the 2015 judgment quashing NJAC, SC had quoted Justice Pal as saying “Consensus within the collegium is sometimes resolved through a trade-off resulting in dubious appointments with disastrous consequences for the litigants and the credibility of the judicial system. Besides, institutional independence has also been compromised by growing sycophancy and lobbying within the system. ” Justice J Chelameswar had approved NJAC in his dissent. Justice Kurian Joseph acknowledged the opaqueness charge and said, “… the Collegium system lacks transparency, accountability and objectivity. ”

Clashes of EC: with govt, within EC

1989-2009

From the archives of "India Today"

1989: Rajiv Gandhi expands the EC by handpicking two members. Commits impropriety by announcing poll dates.

1990: V.P. Singh sacks two election commissioners saying they were partisan. S.S. Dhanoa challenges removal in the SC. Appeal is rejected.

1993: Narasimha Rao expands EC to rein in T.N. Seshan who approached SC. Apex Court upholds order. In Dhanoa and Seshan cases, court treats the commissioners as equals but says CEC had powers to recommend their removal. Battle renewed

2005: BJP objects to Chawla’s elevation as election commissioner, claiming he was partial to the Congress.

2006-07: Chawla and Gopalaswami lock horns over poll dates for Uttar Pradesh and Chawla’s decision to consult the MEA on Sonia Gandhi accepting a Belgian honour.

2008: CEC sends notice asking Chawla why he should not be sacked for being partisan. Finds Chawla’s reply unsatisfactory.

2009: Gopalaswami recommends to the President that Chawla be dismissed

Election commissioners, selection of

Debates in Constituent Assembly, 1949; subsequent changes

Right from the time the Constitution was being finalised through debates in the Constituent Assembly in 1949, there has been unanimity that elections must be insulated from executive interference.

The Fundamental Rights Committee had recommended recognising “independence of elections and the avoidance of any interference by the executive in the elections to the legislatures“ as a fundamental right. But, after long debate, the Constituent Assembly , in the words of B R Ambedkar, resolved that “while there was no objection to regard the matter as of fundamental importance, it should be provided for in some other part of the Constitution and not in the chapter dealing with fundamental rights“.

The original draft Constitu tion had provided that the chief election commissioner and election commissioners would be appointed by the President.Many members had expressed reservations over giving unbridled powers to the PM to choose a person of his choice as the CEC. They felt such a personalised selection process was sure to impede the independence of the commission.

This had forced Ambedkar to amend the original draft provision. The amended version, which is now Article 324(2), said, “The Election Commission shall consist of the CEC and such number of other election commissioners, if any, as the President may from time to time fix and the appointment of CEC and other election commissioners shall, subject to the provisions of any law made in that behalf by Parliament, be made by the President.“

`Subject to law made by Parliament' was inserted to keep the doors open for devising a suitable mechanism in future. For four decades, the EC was a single-member body with the CEC as its head. From October 16, 1989 till January 1, 1990, it became a three-member body . From January 2, 1990, when T N Seshan became CEC, and up to September 30, 1993, it again became a singlemember commission.

For decades, the commission was subservient to the ruling party -in fixing poll schedule and blinking at electoral malpractices. Seshan changed it all. He gradually assumed grotesque independence and recklessly cracked the `model code of conduct' whip. He refused all requests from the ruling party, even for postponement of bye-elections involving Sharad Pa war and Pranab Mukherjee.

An upset government brought an ordinance in 1993 to rein in the “too independent“ CEC. It appointed two more election commissioners and gave them equal status with that of the CEC. An angry Seshan challenged the validity of the ordinance in the Supreme Court. A five-judge bench rebuffed Seshan [1995 (4) SCC 611] and upheld appo intment of the two ECs.

In the past, the SC had never commented on the process for selection and appointment of CEC and ECs. In 2006, then CEC B Tandon had written to then President A P J Abdul Kalam proposing a sevenmember collegium headed by the PM for selection of CEC and ECs. The other members in the proposed collegium were Lok Sabha Speaker, law mi nister, leaders of opposition in LS and RS, an SC judge nominated by the CJI and deputy chairman of RS.

Three years later, then CEC N Gopalaswami wrote to then President Pratibha Patil proposing a six-member collegium headed by the PM for selection of CEC and ECs. the collegium proposed by Gopalaswami excluded the SC judge. Both Tandon and Gopalaswami had said such collegiums were in action for selection of central vigilance commissioner and chairman and members of National Human Rights Commission. When Navin Chawla was set to become the CEC, BJP leaders L K Advani and Arun Jaitley had whole-heartedly supported the concept of a collegium for selection of the CEC and ECs.

Last week, the SC picked the threads from the ex-CECs' letters and asked the government, “The President appoints the CEC and ECs. The Constitution says it will be subject to any law enacted by Parliament. But till date, no law has been enacted. In such a scenario, in the absence of a law and till Parliament legislates on this issue, would it not be appropriate to institutionalise the appointment process by laying down certain norms?“ Maintaining independence of the CEC and ECs and keeping them free from political masters was the main object behind the SC's query .The NDA government opposed and said, “Rightly or wrongly , Parliament has decided not to enact a law. If Parliament says there is no need for a law, can the Supreme Court step into the legislative arena and attempt to fill the perceived gaps which do not exist? This will be improper on the part of the court.“

Given the earlier statements of Advani and Jaitley , the NDA government may not have difficulty in drafting a bill for introduction in Parliament. But the government and the SC must remember the golden words of caution uttered by K M Munshi in the Constituent Assembly on independence of the EC, which he felt would have a large army of officials given the enormity of the task entrusted to it.

“Now, all this army cannot be set up as a machinery independent of the government. It is not possible nor advisable to have a kingdom within a kingdom, so that election matters could be left to an entirely independent organ of the government. A machinery , so independent, cannot be allowed to sit as a kind of super-government to decide which government shall come to power. There will be great political danger if the Election Commission becomes such a political power in the country .“

Model code violations

2010-12

[Bharti Jain, ‘Selective amnesia’: EC rebuts ex-CEC on its handling of hate speech, February 14, 2020: The Times of India]

S Y Quraishi

led EC from 2010 to 2012, had in an opinion piece published in a daily on February 8, 2020, wondered why EC had stopped short of filing FIRs against Union minister Anurag Thakur and BJP MP Parvesh Verma under Representation of the People Act (RP Act) or Section 153 of IPC for hate speech despite finding them “guilty of offences deserving punishment” under Section 123 and 125 of RP Act. He, however, appreciated EC’s decision to drop the two from BJP’s list of star campaigners and temporarily bar them from campaigning.

In a reply sent to Quraishi on February 13, 2020 — a copy of which is with TOI — deputy election commissioner Sandeep Saxena put on record each of the model code violation proceedings undertaken during Quraishi’s own term. “It would be seen from the enclosed list that no action was taken by the then Commission during this period under Sections 123 and 125 of RP Act 1951/153 of IPC 1860,” he pointed out.

EC cites nine notices issued for polls during Quraishi’s term

EC cited the nine showcause notices issued for elections held between July 30, 2010 and June 10, 2012, coinciding with Quraishi’s term. While five notices were issued in 2012 UP poll, three in 2011 West Bengal poll, two in 2011 Tamil Nadu poll and one in 2010 Bihar poll. As per final outcome of these cases, advisories were issued in five, warning issued in two and remaining two cases closed. No directions were issued to lodge FIR in any of the cases.

No model code of conduct notices were issued during polls in Assam, Kerala, Puducherry, Goa, Manipur and Uttarakhand in the relevant period.

Citing the notice issued to then law minister Salman Khurshid for announcing 9% reservation for minorities within 27% OBC quota during UP poll, EC recalled that he was subsequently censured. Khurshid later reiterated the announcement, after which EC wrote to President seeking his intervention. Khurshid finally regretted his statements before EC, after which latter decided not to take further action.

EC also issued a notice to BSP’s S C Mishra in 2012 for his repeated references to Dalit-Brahmin political combination. Though Mishra did not reply, EC took a lenient view and merely hoped Mishra would be more careful in the future. Another notice went to former Union minister Beni Prasad Verma for making promises to Muslims, but after he regretted the same, EC did not press for further action. Even then Union minister Sri Prakash Jaiswal received an EC notice for threatening President’s rule in UP. Jaiswal claimed his statement was distorted and EC concluded there was no threat of intimidation of votes.

In West Bengal poll in 2011, CPM’s Anil Basu had made obscene remarks against Trinamool chief Mamata Banerjee.EC only conveyed its severe displeasure and warned him to be more careful in the future.

Reforms, proposed and actual

Govt thwarts EC bid to bar utility bill defaulters

Govt thwarts EC bid to bar utility bill defaulters, October 9, 2017: The Times of India

The government has rejected a proposal from the Election Commission (EC) to amend the Representation of the People Act to bar candidates from contesting parliamentary or assembly elections if they have not cleared their dues such as house rent in government accommodation, electricity and water bills.

The EC had in a communication to the law ministry requested amending the election laws to include failure to clear dues of public utilities as a disqualification from contesting Lok Sabha and assembly polls.

Barring candidates will require amendment to Chapter III of the RP Act which deals with electoral offences. A new clause will have to be inserted therein for disqualification “on the ground of being a defaulter of public dues“.

However, in its response to the election watchdog, the law ministry had said the proposal was “not desirable“. According to the law ministry , the ban would not be desirable as the authority issuing no-dues certificate or no-objection certificate to a candidate could be biased and may not give the required papers.

The ministry also said in cases of dispute on the dues, the matter could be referred to a court and may take time to settle. In such cases, it would not be desirable to deny the candidate with the nodues certificate.

In July , 2015 the Delhi High Court had through an order asked the EC to “consider the possibility , if any, of putting any impediment to a defaulter of public dues contesting election, to ensure quick recovery of the said dues“.

Based on the judgment, the commission had recently made it mandatory for candidates contesting polls to furnish a `no-dues certificate' from the agency providing electricity, water and telephone connections to their accommodation.

This led to some candidates missing filing their nomination papers in the recent assembly polls as they had failed to get the required no-dues certificate. There was, however, no legal backing to such instructions from the EC.

See also

Chief Election Commissioners Of India

Election Commission of India

Election laws, rules. procedures: India

Elections in India: behaviour and trends (2014)

Elections in India: behaviour and trends (historical)