Demonetisation of high value currency- 2016: India

(→1978) |

(→1946) |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

=1946= | =1946= | ||

See graphic for the broad outline. The Mehta Parikh case study is only for historians and Income Tax lawyers. Lay readers may skip it. | See graphic for the broad outline. The Mehta Parikh case study is only for historians and Income Tax lawyers. Lay readers may skip it. | ||

| + | ==What happened in 1946== | ||

| + | [http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/the-cycles-of-demonetisation-a-looks-back-at-two-similar-experiments-in-1946-and-1978/articleshow/55379367.cms By Vikram Doctor, ET Bureau | Nov 12, 2016, The cycles of demonetisation: A look back at two similar experiments in 1946 and 1978 The Economic Times] | ||

| + | |||

| + | In West Bengal, a pundit had to postpone the marriage of his daughter. The Rs 1,000 notes he had scraped together for the marriage were no longer legal tender. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Nainital a big businessman fell over and died from heart failure when he went to hand in his Rs 1,000 notes. And in Calcutta, an enterprising gentleman who handed in notes to the value of Rs 6.03 lakh, the largest amount deposited that day, claimed he had got them for “an official secret which could not be disclosed to the public.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | These stories are from on January 12, 1946, when the pre-Independence government of India passed the High Denomination Bank Notes (Demonetisation) Ordinance. The background was World War II, which had just got over, but during which businessmen in India were supposed to have made huge fortunes supplying the Allied war effort and were concealing their profits from the tax department. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Letter writers to the Times of India (ToI) exulted at this first formal demonetisation in India. “The money that is concentrated in the hands of these people is not simply wealth. It is the life blood of thousands of Indians who starved and died during the last five years while black marketeers went on piling up money in their safes,” fumed SR Rangnekar from Bombay (now Mumbai). He advised the government to follow this up by cracking down on their stocks of gold “if they exceed 100 tolas.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | G Pingle from Kalyan noted snidely that many black marketing businessmen “tried to play the role of true nationalists. It passes my comprehension why so-called nationalists did not make any attempt to improve the condition of their war-weary fellow men.” Eric Miranda from Bandra suggested that people handing in high-value notes “might even be allowed to smoke a cigarette made out of one of these notes, as some are now doing, as some consolation.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | A writer using the name Non-Idealist suggested, more practically, that the government not waste time moralising about the black market, but just focus on getting the money. Noting that a large amount of notes might just never get handed in because they could not be accounted for, and hence go to waste (or be used to make cigarettes), the writer suggested the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) simply offer 30-40% of the value of the notes, with no questions asked. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Indian nationalist leaders, who hadn’t been party to the decision, sounded dubious about its effects. Rajendra Prasad, who would become the first president of India, declared that “while we, Congressmen, have no sympathy with profiteers and dealers in the black market, it is not right to penalise honest people who in good faith have their savings in notes of demonetised value… A large number of people belonging to the middle and lower middle classes will be hit hard.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | And in a display of scepticism about government regulations that, sadly, would not carry over to the later Indian government, Prasad wondered how the problem had been created in the first place: “Many of the wartime ordinances succeeded in complicating the problems which they were intended to solve and in creating opportunities for corruption. The new ordinances are not going to fare any better.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The similarity of all these reactions, from the fulminations of letter writers (Net commentators today), to the need for a mysterious, corrupt group to blame, to concerns for the impact on regular people, all suggest that there is something cyclical about demonetisation. Even the secrecy with which the current government pulled it off has parallels in 1946. “Never was a secret so well kept in Delhi,” wrote ToI on January 26. Even government officials were left with high-value notes to hand in. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ToI wrote that only eight officials knew about the plan, including the RBI governor and the finance member of the Viceroy’s Council (the equivalent of today’s finance minister). “In order to be issued on Saturday, January 12, the ordinance had to be flown in a special plane to Poona for the Viceroy’s signature. It was then flown back.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | During the discussions with governor Chintaman Deshmukh (later to be Nehru’s finance minister), the officers took notes and typed drafts themselves, without the help of secretaries. “Handwritten notes exchanged between these officials were carefully burnt. No carbon copy of the documents was made or kept.” Even extra staff wasn’t allocated to the RBI’s currency department just in case that raised suspicions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The collections made justified the precautions. ToI reported that currency notes to the value of Rs 47 crore had been deposited across India, with Bombay in the lead with Rs 27 crore, followed by Calcutta (now Kolkata) with Rs 7 crore, Karachi with Rs 3 crore, Lahore with Rs 2.5 crore and Madras (now Chennai) with Rs 60 lakhs. New Delhi, as a newly constructed government town, didn’t seem to count at all. The Indian princes weren’t exempt, but were allowed to use a special form approved by the crown representative in their state. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For a while after 1946, black money ceased to be a major issue. The demonetisations that took place were technical, dealing with the currencies of the native states. In 1949, for example, Kutch’s koris were converted; they were pure silver and were causing problems in the bullion market. After the takeover of Hyderabad, the Osmania sicca, a 148-year-old currency, was converted to Indian rupees in 1957, with a grace period of two years for the change. In 1963-64 the old annas and pice coins were converted to paise, also a technical demonetisation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But around that time, the rumours about black money started rising again. In 1965, finance minister TT Krishnamachari had to face questioning from increasingly assertive opposition members about the quantum of black money, and using demonetisation to stop it (high-value notes came back in 1954). | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''1965- 1972 ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | On April 20, 1965, Krishnamachari replied in Parliament that “demonetisation was neither feasible nor would produce results.” He felt that estimates of black money were hugely over inflated and what did exist had been converted to “bonds, property and shares,” all beyond the reach of demonetisation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Yet the demand never went away. In 1970, it got a boost of sorts when neighbouring Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) conducted a truly radical demonetisation that extended to Rs 100 and Rs 50 notes. A commission on direct taxation was set up under Justice Kailas Nath Wanchoo that looked at the issue and, perhaps inspired by Ceylon, it suggested even demonetising down to Rs 10 notes! | ||

| + | |||

| + | This seems to have been more on the lines of what will happen with our current Rs 500s, where the denomination still exists, but the physical notes will change. As Prem Shankar Jha noted in a column in ToI on August 28, 1972, this in itself would have required a major feat: “The government will have to print no less than 3,500 million currency notes – at least ten times as many as in a normal year – and transport them to every treasury office, bank and post office in the country.” It would, he pointed out, be impossible to do this secretly. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In a sign of the rising demand for action though, Jha concluded his piece by suggesting that, despite the logistical problems, it was needed as a scare: “The real value of demonetisation lies in its therapeutic effect on the economy. Large numbers of habitual tax evaders conceal their incomes only because years of laxity and permissiveness in the present tax laws have lulled them into a sense of security.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is an echo here of [the 2016] Prime Minister [Mr Modi]’s speech, urging India to accept the short-term pain for the long-term, cleansing effect. And it shouldn’t be a surprise that later that same year the Jan Sangh, the precursor to the Bharatiya Janata Party, adopted demonetisation in a resolution at a party conference in Jaipur. “The resolution said between high prices and high taxes the citizen was being ‘crushed’,” wrote ToI, and one can see an argument that the flow of black money was causing the first and was caused by the latter. | ||

| + | ===1978=== | ||

| + | So when Janata came to power, with the Jan Sangh as part of the coalition, demonetisation was always likely to be on the agenda. Again, it was put into effect with speed and secrecy. According to the RBI’s official history, on January 14, 1978, R Janakiraman, a senior RBI official was asked to go to Delhi on “some urgent work.” Despite being told to go alone, he took an assistant and when they reached they were told they had 24 hours in which to draft a demonetisation ordinance. | ||

| + | |||

| + | They were forbidden from communicating with RBI headquarters in Bombay. They managed to get a copy of the 1946 ordinance and used it to draft a new one. On January 16 it was announced that Rs 1,000, Rs 5,000 and Rs 10,000 notes were being withdrawn from circulation. As with Modi’s announcement on November 8, the next day was declared a public holiday to allow banks to prepare for the onslaught. The public was given just three days to exchange their notes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Long queues formed in front of RBI and State Bank of India offices from very early in the morning. Additional counters were set up but, according to the RBI history, January 18 “started with utter confusion over the issue of declaration forms at the Reserve Bank headquarters at Bombay and working hours were stretched to 6.30 pm.” Tempers rose and there was a particular outcry from foreign tourists who faced the prospect of running out of legal money far from home. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Despite the problems, finance minister HM Patel declared he was pleased. ToI quoted him saying, a bit cryptically, “You will see me smiling whatever the result.” He deflected suggestions that it would harm trade and industry by saying the measure “would affect smugglers who were in any case on the fringes of trade and industry.” Rather oddly, he played down the impact on black money since, for that, he said it would have been necessary to demonetise Rs 100 notes. This measure, he said, was just to reduce the money used in illegal transactions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If the finance minister was vague, RBI governor IG Patel was not. In his memoirs, Glimpses of Indian Economic Policy, he made clear he went along with demonetisation reluctantly. He had pointed out to the finance minister that “such an exercise seldom produces striking results.” People who have black money on a substantial scale rarely keep it in cash. “The idea that black money or wealth is held in the form of notes tucked away in suit cases or pillow cases is naïve.” Patel pointed out that even those who are caught with black money can usually find agents who will convert the notes through a number of small transactions “for which explanations cannot be reasonably sought.” Yet the government was insistent, and so “the gesture had to be made, and produced much work and little gain.” Patel didn’t mention it, but another former finance minister C Subramaniam suggested that, then as now, the real aim was political and aimed against other parties. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The same point was made by two economists--CN Vakil and PR Brahmananda. They pointed out that the measure might have had some merit if it had reduced money supply, perhaps by exchanging the notes for a little less. As it stood it was just “a publicity boost” to the government and they recalled how the 1946 demonetisation had just resulted in Rs 10 crore going out of the circulation and the recent Sri Lankan experiment had much the same impact: “One guess is that the present measure has primarily a political and not economic objective. In such a case it becomes a business in and among politicians.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The rapidity with which black money became an issue again in following decades suggests that the doubters had a point. Perhaps demonetisation is always more of a political gimmick. Perhaps, as Jha had suggested, it is a needed warning to discourage black marketers – though as the doubters might argue, the question remains if the really big players are affected, while regular people suffer the pain. | ||

| + | |||

==In 1946, too, IT officers smelt black money in high notes== | ==In 1946, too, IT officers smelt black money in high notes== | ||

'' In 1946, too, many rich Indians had black money as in 1978 and 2016. Even then they claimed that Income Tax officers were harassing them. Take this case that was heard in the courts from 1946 to 1956. '' | '' In 1946, too, many rich Indians had black money as in 1978 and 2016. Even then they claimed that Income Tax officers were harassing them. Take this case that was heard in the courts from 1946 to 1956. '' | ||

Revision as of 21:00, 13 November 2016

The Times of India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

1946

See graphic for the broad outline. The Mehta Parikh case study is only for historians and Income Tax lawyers. Lay readers may skip it.

What happened in 1946

In West Bengal, a pundit had to postpone the marriage of his daughter. The Rs 1,000 notes he had scraped together for the marriage were no longer legal tender.

In Nainital a big businessman fell over and died from heart failure when he went to hand in his Rs 1,000 notes. And in Calcutta, an enterprising gentleman who handed in notes to the value of Rs 6.03 lakh, the largest amount deposited that day, claimed he had got them for “an official secret which could not be disclosed to the public.”

These stories are from on January 12, 1946, when the pre-Independence government of India passed the High Denomination Bank Notes (Demonetisation) Ordinance. The background was World War II, which had just got over, but during which businessmen in India were supposed to have made huge fortunes supplying the Allied war effort and were concealing their profits from the tax department.

Letter writers to the Times of India (ToI) exulted at this first formal demonetisation in India. “The money that is concentrated in the hands of these people is not simply wealth. It is the life blood of thousands of Indians who starved and died during the last five years while black marketeers went on piling up money in their safes,” fumed SR Rangnekar from Bombay (now Mumbai). He advised the government to follow this up by cracking down on their stocks of gold “if they exceed 100 tolas.”

G Pingle from Kalyan noted snidely that many black marketing businessmen “tried to play the role of true nationalists. It passes my comprehension why so-called nationalists did not make any attempt to improve the condition of their war-weary fellow men.” Eric Miranda from Bandra suggested that people handing in high-value notes “might even be allowed to smoke a cigarette made out of one of these notes, as some are now doing, as some consolation.”

A writer using the name Non-Idealist suggested, more practically, that the government not waste time moralising about the black market, but just focus on getting the money. Noting that a large amount of notes might just never get handed in because they could not be accounted for, and hence go to waste (or be used to make cigarettes), the writer suggested the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) simply offer 30-40% of the value of the notes, with no questions asked.

The Indian nationalist leaders, who hadn’t been party to the decision, sounded dubious about its effects. Rajendra Prasad, who would become the first president of India, declared that “while we, Congressmen, have no sympathy with profiteers and dealers in the black market, it is not right to penalise honest people who in good faith have their savings in notes of demonetised value… A large number of people belonging to the middle and lower middle classes will be hit hard.”

And in a display of scepticism about government regulations that, sadly, would not carry over to the later Indian government, Prasad wondered how the problem had been created in the first place: “Many of the wartime ordinances succeeded in complicating the problems which they were intended to solve and in creating opportunities for corruption. The new ordinances are not going to fare any better.”

The similarity of all these reactions, from the fulminations of letter writers (Net commentators today), to the need for a mysterious, corrupt group to blame, to concerns for the impact on regular people, all suggest that there is something cyclical about demonetisation. Even the secrecy with which the current government pulled it off has parallels in 1946. “Never was a secret so well kept in Delhi,” wrote ToI on January 26. Even government officials were left with high-value notes to hand in.

ToI wrote that only eight officials knew about the plan, including the RBI governor and the finance member of the Viceroy’s Council (the equivalent of today’s finance minister). “In order to be issued on Saturday, January 12, the ordinance had to be flown in a special plane to Poona for the Viceroy’s signature. It was then flown back.”

During the discussions with governor Chintaman Deshmukh (later to be Nehru’s finance minister), the officers took notes and typed drafts themselves, without the help of secretaries. “Handwritten notes exchanged between these officials were carefully burnt. No carbon copy of the documents was made or kept.” Even extra staff wasn’t allocated to the RBI’s currency department just in case that raised suspicions.

The collections made justified the precautions. ToI reported that currency notes to the value of Rs 47 crore had been deposited across India, with Bombay in the lead with Rs 27 crore, followed by Calcutta (now Kolkata) with Rs 7 crore, Karachi with Rs 3 crore, Lahore with Rs 2.5 crore and Madras (now Chennai) with Rs 60 lakhs. New Delhi, as a newly constructed government town, didn’t seem to count at all. The Indian princes weren’t exempt, but were allowed to use a special form approved by the crown representative in their state.

For a while after 1946, black money ceased to be a major issue. The demonetisations that took place were technical, dealing with the currencies of the native states. In 1949, for example, Kutch’s koris were converted; they were pure silver and were causing problems in the bullion market. After the takeover of Hyderabad, the Osmania sicca, a 148-year-old currency, was converted to Indian rupees in 1957, with a grace period of two years for the change. In 1963-64 the old annas and pice coins were converted to paise, also a technical demonetisation.

But around that time, the rumours about black money started rising again. In 1965, finance minister TT Krishnamachari had to face questioning from increasingly assertive opposition members about the quantum of black money, and using demonetisation to stop it (high-value notes came back in 1954).

1965- 1972

On April 20, 1965, Krishnamachari replied in Parliament that “demonetisation was neither feasible nor would produce results.” He felt that estimates of black money were hugely over inflated and what did exist had been converted to “bonds, property and shares,” all beyond the reach of demonetisation.

Yet the demand never went away. In 1970, it got a boost of sorts when neighbouring Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) conducted a truly radical demonetisation that extended to Rs 100 and Rs 50 notes. A commission on direct taxation was set up under Justice Kailas Nath Wanchoo that looked at the issue and, perhaps inspired by Ceylon, it suggested even demonetising down to Rs 10 notes!

This seems to have been more on the lines of what will happen with our current Rs 500s, where the denomination still exists, but the physical notes will change. As Prem Shankar Jha noted in a column in ToI on August 28, 1972, this in itself would have required a major feat: “The government will have to print no less than 3,500 million currency notes – at least ten times as many as in a normal year – and transport them to every treasury office, bank and post office in the country.” It would, he pointed out, be impossible to do this secretly.

In a sign of the rising demand for action though, Jha concluded his piece by suggesting that, despite the logistical problems, it was needed as a scare: “The real value of demonetisation lies in its therapeutic effect on the economy. Large numbers of habitual tax evaders conceal their incomes only because years of laxity and permissiveness in the present tax laws have lulled them into a sense of security.”

There is an echo here of [the 2016] Prime Minister [Mr Modi]’s speech, urging India to accept the short-term pain for the long-term, cleansing effect. And it shouldn’t be a surprise that later that same year the Jan Sangh, the precursor to the Bharatiya Janata Party, adopted demonetisation in a resolution at a party conference in Jaipur. “The resolution said between high prices and high taxes the citizen was being ‘crushed’,” wrote ToI, and one can see an argument that the flow of black money was causing the first and was caused by the latter.

1978

So when Janata came to power, with the Jan Sangh as part of the coalition, demonetisation was always likely to be on the agenda. Again, it was put into effect with speed and secrecy. According to the RBI’s official history, on January 14, 1978, R Janakiraman, a senior RBI official was asked to go to Delhi on “some urgent work.” Despite being told to go alone, he took an assistant and when they reached they were told they had 24 hours in which to draft a demonetisation ordinance.

They were forbidden from communicating with RBI headquarters in Bombay. They managed to get a copy of the 1946 ordinance and used it to draft a new one. On January 16 it was announced that Rs 1,000, Rs 5,000 and Rs 10,000 notes were being withdrawn from circulation. As with Modi’s announcement on November 8, the next day was declared a public holiday to allow banks to prepare for the onslaught. The public was given just three days to exchange their notes.

Long queues formed in front of RBI and State Bank of India offices from very early in the morning. Additional counters were set up but, according to the RBI history, January 18 “started with utter confusion over the issue of declaration forms at the Reserve Bank headquarters at Bombay and working hours were stretched to 6.30 pm.” Tempers rose and there was a particular outcry from foreign tourists who faced the prospect of running out of legal money far from home.

Despite the problems, finance minister HM Patel declared he was pleased. ToI quoted him saying, a bit cryptically, “You will see me smiling whatever the result.” He deflected suggestions that it would harm trade and industry by saying the measure “would affect smugglers who were in any case on the fringes of trade and industry.” Rather oddly, he played down the impact on black money since, for that, he said it would have been necessary to demonetise Rs 100 notes. This measure, he said, was just to reduce the money used in illegal transactions.

If the finance minister was vague, RBI governor IG Patel was not. In his memoirs, Glimpses of Indian Economic Policy, he made clear he went along with demonetisation reluctantly. He had pointed out to the finance minister that “such an exercise seldom produces striking results.” People who have black money on a substantial scale rarely keep it in cash. “The idea that black money or wealth is held in the form of notes tucked away in suit cases or pillow cases is naïve.” Patel pointed out that even those who are caught with black money can usually find agents who will convert the notes through a number of small transactions “for which explanations cannot be reasonably sought.” Yet the government was insistent, and so “the gesture had to be made, and produced much work and little gain.” Patel didn’t mention it, but another former finance minister C Subramaniam suggested that, then as now, the real aim was political and aimed against other parties.

The same point was made by two economists--CN Vakil and PR Brahmananda. They pointed out that the measure might have had some merit if it had reduced money supply, perhaps by exchanging the notes for a little less. As it stood it was just “a publicity boost” to the government and they recalled how the 1946 demonetisation had just resulted in Rs 10 crore going out of the circulation and the recent Sri Lankan experiment had much the same impact: “One guess is that the present measure has primarily a political and not economic objective. In such a case it becomes a business in and among politicians.”

The rapidity with which black money became an issue again in following decades suggests that the doubters had a point. Perhaps demonetisation is always more of a political gimmick. Perhaps, as Jha had suggested, it is a needed warning to discourage black marketers – though as the doubters might argue, the question remains if the really big players are affected, while regular people suffer the pain.

In 1946, too, IT officers smelt black money in high notes

In 1946, too, many rich Indians had black money as in 1978 and 2016. Even then they claimed that Income Tax officers were harassing them. Take this case that was heard in the courts from 1946 to 1956.

Messrs Mehta Parikh & Co vs The Commissioner Of [Income Tax?] on 10 May, 1956 Indian Kanoon

The appellants were a partnership firm doing business in Mill Stores at Ahmedabad. Their head office was in Ahmedabad and their branch office in Bombay.

The Governor-General on 12th January 1946 promulgated the High Denomination Bank Notes (Demonetisation) Ordinance, 1946 and high denomination bank notes ceased to be legal tender on the expiry of 12th day of January 1946.

Pursuant to clause 6 of the Ordinance the appellants on 18th January 1946 encashed high denomination notes of Rs. 1,000 each of the face value of Rs. 61,000 [at least Rs.61 lakh at 2016 prices].

During the assessment proceedings for the year 1947-48 the Income-tax Officer called upon the appellant to prove from whom and when the said high denomination notes of Rs. 61,000 were received by the appellants and also the bona fides of the previous owners thereof. After examining the entries in the books of account of the appellants and the position of the Cash Balances on various dates from 20th December 1945 to 18th January 1946 and the nature and extent of the receipts and payments during the relevant period, the Income-tax Officer came to the conclusion that in order to sustain the contention of the appellants he would have to presume that there were 18 high denomination notes of Rs. 1,000 each in the Cash Balance on 1st January 1946 and that all cash receipts after 1st January 1946 and before 13th January 1946 were received in currency notes of Rs. 1,000 each, a presumption which he found impossible to make in the absence of any evidence. He, therefore, added the sum of Rs. 61,000 to the assessable income of the appellants from undisclosed sources.

The cash book entries from 20th December 1945 up to 18th January 1946 were put in before the Income-tax Officer and they showed that on 28th December 1945 Rs. 20,000 were received from the Anand Textiles, and there was an opening balance of Rs. 18,395 on 2nd January 1946. Rs. 15,000 were received by the appellants on 7th January 1946 from the Sushico Textiles and Rs. 8,500 were received by them on 8th January 1946 from Manihen, widow of Shah Maneklal Nihalchand. Various other sums were also received by the appellants from 2nd January 1946 up to and inclusive of 1 1 th January 1946, which were either multiples of Rs. 1,000 or were over Rs. 1,000 and were thus capable of having been paid to the appellants in high denomination notes of Rs. 1,000. There was a cash balance of Rs. 69,891-2-6 with the appellants on 12th January 1946, when the High Denomination Bank Notes (Demonetisation) Ordinance 1946 was promulgated and it was the case of the appellants that they had then in their custody and possession 61 high denomination notes of Rs. 13000, which they encashed through the Eastern Bank, on 18th January 1946. The appellants further sought to support their contention by procuring before the Appellate Assistant Commissioner the affidavits of Kuthpady Shyama Shetty, General Manager of Messrs Shree Anand Textiles, in regard to payment to the appellant is of a sum of Rs. 20,000 in Rs. 1,000 currency notes on 28th December 1945, Govindprasad Ramjivan Nivetia, proprietor of Messrs Shusiko Textiles, in regard to payment to the appellants of a sum of Rs. 15,000 in Rs. 1,000 currency notes on 6th January 1946 and Bai Maniben, widow of Shah Maneklal Nihalchand, in regard to payment to the appellants of a sum of Rs. 8,500 (Rs. 8,000 thereout being in Rs. 1,000 currency notes) on 8th January 1946. The appellants were not in a position to give further particulars of Rs. 1,000 currency notes received by them during the relevant period, as they were not in the habit of noting these particulars in their cash book -and therefore relied upon the position as it could be spelt out of the entries in their cash book coupled with these affidavits in order to show that on 12th January 1946 they had in their cash balance of Rs. 69,891-2-6, the 61 high denomination currency notes of Rs. 1,000 each, which they encashed on 18th January 1946 through the Eastern Bank. Both the Income-tax Officer and the Appellate Assistant Commissioner discounted this suggestion of -the appellants by holding that it was impossible that the appellants had on hand on 12th January 1946, the 61 high denomination currency notes of Rs. 1,000 each, included in their cash balance of Rs. 69,891-2-6. The calculations., which they made involved taking into account all payments received by the appellants from and after 2nd January 1946, which were either multiples of Rs. 1,000 or were over Rs. 1,000. There was a cash balance of Rs. 18,395-6-6 on band on 2nd January 1946, which could have accounted for 18 such notes. The appellants received thereafter as shown in their cash book several sums of monies aggregating to over Rs. 45,000 in multiples of Rs. 1,000 or sums over Rs. 1,000, which could account for 45 other notes of that high denomination, thus making up 63 currency notes of the high denomination of Rs. 1,000 and these 61 currency notes of Rs. 1,000 each, which the appellants encashed on 18th January 1946 could as well have been in their custody on 12th January 1946. This was, however, considered impossible by both the Income-tax Officer and the Appellate Assistant Commissioner as they could not consider it within the bounds of possibility that each and every .payment received by the appellants after 2nd January 1946 in multiples of Rs. 1,000 or over Rs. 1,000 was received by the appellants in high denomination notes of Rs. 1,000 each.' It was by reason of their visualisation of such an impossibility that they negatived the appellants' contention.

1978

Surprise & panic: History repeats itself 38 yrs later, Nov 09 2016 : The Times of India

Summary

2016 was not the first time high value currency notes were demonetised.

In January 1978, the Morarji Desai-led Janata Party government had demonitised Rs 1,000, Rs 5,000 and Rs 10,000 notes to curb black money .This was less than a year after the Emergency was lifted.

Old-timers remember that the decision then too had taken the public by surprise, leading to panic and a rush to banks although people were given time to exchange old notes.

To put things in perspective, a Rs 1,000 note in 1978 could buy 5 sq ft of real estate space in south Mumbai. In 2016, a Rs 500 note would not even be worth 100th of a square foot.

Senior advocate Anil Harish said people with unaccounted money were reluctant to deposit their high denomination currency in banks because of fear of income tax sleuths. “At places like Crawford Market and Zaveri Bazar, people were selling Rs 1,000 notes for as little as Rs 300,“ he said.

At banks, people were asked to fill in a form when they came to exchange old notes.The banks would inform the I-T cell if people walked in with unusually large amounts. “If they were unable to explain the source of income, the I-T wing would levy the prevalent tax, which was as high as 90% in those days,“ he added.

Said advocate Nishith Desai, “I remember 1978, when people had to go with bags full of cash to the bank. It is an excellent step, but the idea is old.“

A senior chartered accountant with Kalyaniwala & Mistry said, “If you want to flush out black money , it is a good step. In 1978 there was no great disruption, however, since the notes were not with common people. Then they had demonetised Rs 1,000 notes which had a huge monetary value. The 500 and 1,000 rupee notes do not have the same value today; even the average man on the street will have these notes.“

RBI’s history

In 1978, the Janata Party coalition government, which had come to power a year earlier, decided to withdraw Rs1,000, Rs5,000 and Rs10,000 notes by issuing an ordinance on the morning of 16 January that year.

The Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) history (third volume) describes the process in detail. It goes something like this:

On the morning of 14 January 1978, R. Janaki Raman, a senior official from chief accountant’s office in RBI, was asked by a government official over telephone to go to Delhi to discuss matters relating to exchange control.

On reaching the capital, Raman was told that the government had decided to withdraw high-denomination notes and asked to draft the necessary ordinance within a day.

During that period, no communication was allowed with RBI’s central office in Mumbai, “since such contacts could give rise to speculation.”

The draft ordinance was completed on schedule and sent for signature to President N. Sanjiva Reddy in the early hours of 16 January. The news was announced on the All India Radio news bulletin at 9 am on the same day. The ordinance provided that all banks and treasuries would be closed on 17 January.

The then RBI governor I.G. Patel was not in favour of this exercise. According to him, some people in the Janata coalition government saw demonetization as a measure specifically targeted against the allegedly “corrupt predecessor government or government leaders”.

Patel recalled in his book Glimpses of Indian Economic Policy: an Insider’s View, that when finance minister H.M. Patel informed him about the decision to withdraw high-denomination notes, he had pointed out that such exercises seldom produces striking results.

Most people, Patel said, who accept illegal gratification or are otherwise recipients of black money, rarely keep their ill-gotten earnings in the form of currency for long.

The idea that black money or wealth is held in the form of notes tucked away in suitcases or pillow cases is naive, Patel said. In any case even those who are caught napping or waiting will have a chance to convert notes through paid agents as some provision has to be made to convert at par notes tendered in small amounts for which explanation cannot be reasonably sought, he added.

2016: Demonetisation of Rs. 500 and Rs 1000 notes

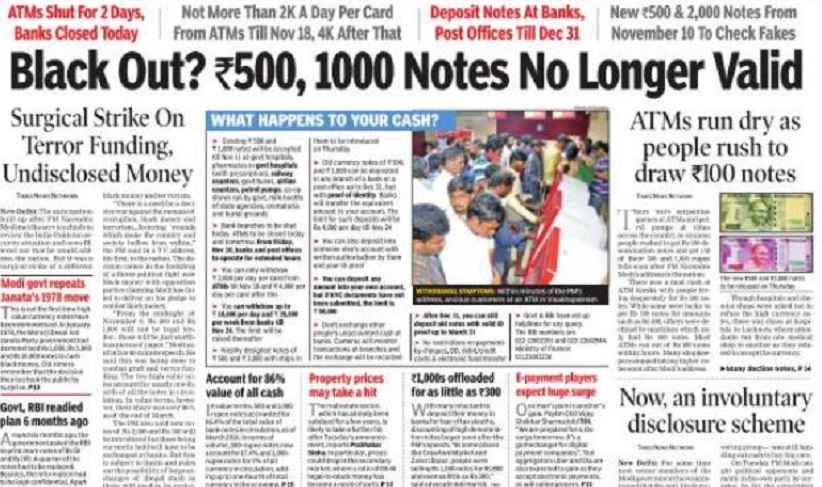

Black Out? Rs 500, 1000 Notes No Longer Valid, Nov 09 2016 : The Times of India

i) thwart Pakistan’s attempts to subvert the Indian rupee (by printing counterfeit Indian currency of high denominations like Rs. 500 and Rs.1,000), and

ii)render useless the illegal cash that political parties had collected and stowed away.

The Times of India

The anticipation built up after PM Narendra Modi met the service chiefs to review the India-Pakistan security situation and news filtered out that he would address the nation. But it was a surgical strike of a different kind, with Modi delivering a stunning surprise by scrapping Rs 1,000 and Rs 500 notes and calling for a “decisive war“ against corruption, black money and terrorism.

“There is a need for a decisive war against the menace of corruption, black money and terrorism...festering wounds which make the country and society hollow from within,“ the PM said in a TV address, his first, to the nation. The decision comes in the backdrop of a fierce political fight over black money with opposition parties claiming Modi has failed to deliver on his pledge to combat black money .

“From the midnight of November 8, Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 will not be legal tender...these will be just worthless pieces of paper,“ Modi said in his 40-minute speech. He said this was being done to combat graft and terror funding. The two high-value notes account for nearly one-fourth of all the notes in circulation. In value terms, however, their share was over 86% as of the end of March.

The PM also said new notes of Rs 2,000 and Rs 500 will be introduced but those being currently held will have to be exchanged at banks. But this is subject to limits and rules out the possibility of large exchanges of illegal stash as these will need to be explained and accounted for. Pitching the decision as a much needed antidote to stamp out the menace of corruption and terror funding, the PM said “Black money and corruption are the biggest obstacles in eradicating poverty...Have you ever thought how these terrorists get their money? Enemies from across the border have run their operations using fake currency notes.“

Describing illegal finan cial activities as the “biggest blot“, Modi said that despite several steps taken by his government over the last twoand-a-half years, India's global ranking on corruption had moved only to 76th position from 100th earlier.

According to the finance ministry , the total number of bank notes in circulation rose by 40% between 2011 and 2016, while the increase in number of notes of Rs 500 denomination was 76% and for Rs 1,000 denomination was 109%.

The World Bank in July 2010 estimated the size of In dia's shadow economy at 20.7% of GDP in 1999, rising to 23.2% in 2007. “A parallel shadow economy corrodes and eats into the vitals of the country's economy ,“ a finance ministry statement said. BLACK OUT? P 2, 13, 14, 15, 25, 29 & 30 It (a parallel shadow econo my) generates inflation, which adversely affects the poor and the middle classes more than others. It deprives government of its legitimate revenues which could have been otherwise used for welfare and development activities,“ a finance ministry statement said.

The move could have political ramifications in the forthcoming state elections as it impacts the capacity of parties to spend unaccounted cash for campaigning and various political payments. ATM withdrawals will be restricted to Rs 2,000 per day and withdrawals from bank accounts will be limited to Rs 10,000 a day and Rs 20,000 a week. Banks will remain closed on Wednesday and ATMs will also not function for the next two days, Modi said.

Apart from depositing money in bank accounts, Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes can also be changed for lower denomination currency notes at designated banks and post offices on production of valid government identity cards like PAN, Aadhaar and election card from November 10 to November 24 with a daily limit of Rs 4,000.

The demonetised currency notes will remain valid for transactions like booking of air tickets, railway and government bus journeys and hospitals till midnight of November 11 and 12. The RBI and the finance ministry have set up helplines to answer questions.

The background

The Hindu, November 9, 2016

RBI board had approved production of Rs. 2,000 denomination notes long ago, say officials

The government’s move to scrap nearly 23.2 billion high-value currency notes of Rs. 500 and Rs. 1,000, was in the pipeline for several months but was kept tightly under wraps, with just a handful of officials in the know.

The Reserve Bank of India’s central board had approved the production of the Rs. 2,000 notes several months ago and even began production of the new Rs. 500 and Rs. 2,000 notes, which are to be issued from November 10 a few months ago.

System ready

“The timing [of the announcement by the Prime Minister] was appropriately chosen as we should be ready with adequate number of notes to replace the existing ones. We had ramped up production in the past few months of the new notes, and hence, it was decided to do it now as we can provide more of them in the weeks and days to come,” said RBI governor Urjit Patel at a briefing.

Security concerns

The case for introducing new notes followed prolonged deliberations within the top echelons of government, based on inputs from security agencies and the central bank.

“There’s been no breach of security features of our notes. But for ordinary citizens, it is often difficult to tell a genuine note from a fake. There’s now a confluence of thought between the government and the Reserve Bank of India. Multiple objectives can be met so this led us to withdraw the legal tender character of Rs. 500 and Rs. 1,000 notes,” Mr Patel pointed out.

Mr. Das said the bold and decisive step to fight black money and the use of fake currency notes to finance terrorism was backed by analysis of India’s currency trends.

‘Disproportionate rise’

“Statistics show that high denomination currency in circulation has risen sharply between 2011 and 2015. When all currency notes grew 40 per cent, Rs. 500 notes in circulation rose by 76 per cent and Rs. 1000 notes went up by 109 per cent. But during this period, the economy expanded by 30 per cent so the circulation of such notes had gone up disproportionately,” he said.

“The long shadow of the ghost economy has to go for the real economy to grow. This will add to our economy’s strength,” Mr. Das stressed.

Terms and conditions for denomination

The Hindu, November 8, 2016

Demonetisation of Rs. 500 and Rs. 1000 notes: RBI explains

From midnight of November 8, 2016, Rs. 500 and Rs.1000 will cease to be legal tender.

Taking the nation by surprise, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced demonetisation of Rs. 1000 and Rs. 500 notes with effect from November 9, 2016 making these notes invalid in a major assault on black money, fake currency and corruption.

In his first televised address to the nation, Mr. Modi said people holding notes of Rs. 500 and Rs. 1000 can deposit the same in their bank and post office accounts from November 10 till December 30.

Six months’ preparation

RBI got 6 months to prepare for this, Nov 09 2016 : The Times of India

Around six months ago [around May 2016], the government asked the RBI to prepare for its latest assault on black money , and told the currency manager to print more Rs 50 and Rs 100 notes, with PM Modi having decided to phase out the current lot of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes earlier this year.

After all the task was hu mongous: replacing 23 billion notes.Besides, the information had to be kept confidential at all costs.

In any case, apart from the PM, only finance minister Arun Jaitley knew, and two senior officers each in the finance ministry and the RBI were in the loop.

The six months were used not just to print enough Rs 50 and Rs 100 currency notes, but also to plan the operations meticulously . This meant that, on Tuesday 8 Nov 2016, the Reserve Bank of India initiated the first “public“ move when its board met around 6pm and recommended the withdrawal of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes. Soon, the government, which was ready with the notification, moved the Cabinet, which met at 6.30pm on Tuesday . The decision was taken and the PM went on air to announce the first demonetisation in 38 years.

The government's calculation was simple. It sees major gains accruing to the economy , beginning with an immediate halt to black money transac tions -at least in the near run. This is ex pected to force peo ple to use only legal channels, which will result in higher tax es in the govern ment's kitty .

While those showing “agricultu ral income“ can still use a possible loop transact in cash, the hole to transact in cash, the window is seen to be limited and the government expects bulk of the funds to flow into the banking system. This itself is going to provide more boost for lending, which has remained subdued, a senior government official said. “We have hastened the printing of these notes,“ RBI governor Urjit Patel said.

Impact on inflation

The Hindu, November 12, 2016

Demonetisation could cut inflation, says Panagariya

The Centre’s demonetisation drive will help lower inflation, NITI Aayog vice chairman Arvind Panagariya said.

“All these makes me believe that their could be some moderation in inflation in the short-term,” Mr. Panagariya said at the Economic Editors’ Conference. “Yields on sovereign bonds softened after the government announced that the present Rs. 500 and Rs. 1,000 currency notes will not be a legal tender from November 9." He also said that eradication of black money from circulation will have some impact on money supply.

“As the black money goes out of the system, the money supply will shrink to some degree. This will reduce the inflation rate in the absence of any open market operations by the RBI,” Mr. Panagariya said.

Savings growth

Banks will see healthy growth in savings account deposits due to this exercise, he said.

“Savings that were kept in different forms particularly in the form of currency notes, they will now move into bank deposits. So we will see some surge in bank deposits,” Mr. Panagariya added.

Separately, Bibek Debroy, member of NITI Aayog dismissed that the demonetisation will have any impact on economic growth.

“Real estate prices were already impacted due to several measures that government had taken in the past,” Mr. Debroy said.

He said black money was never in the calculation of GDP figures, hence the present demonetisation drive will not impact growth.

Cost to RBI

The Hindu, November 9, 2016

New notes to cost RBI more than Rs. 12,000 crore

Sharad Raghavan

By removing the Rs. 1,000 note, the government is doing away with the cheapest note to print in relation to the face value of the note.

Replacing all the Rs. 500 and Rs. 1,000 denomination notes with other denominations, as ordered by the government, could cost the Reserve Bank of India at least Rs. 12,000 crore, based on the number of notes in circulation and the cost incurred in printing them.

Data from a Right to Information answer by the RBI in 2012 shows that it costs Rs. 2.50 to print each Rs. 500 denomination note, and Rs. 3.17 to print a Rs. 1,000 note.

That means that it cost the central bank Rs. 3,917 crore to print the 1,567 crore Rs. 500 notes in circulation, and Rs. 2,000 crore to print the 632 crore Rs. 1,000 notes in circulation currently.

Assuming that the new Rs. 500 notes cost the same to print, then that is an additional Rs. 3,917 crore spent in simply maintaining the same number of notes in circulation.

The new Rs. 2,000 notes are likely to cost about the same or a little more than the Rs. 1,000 notes, which means an additional cost of Rs. 2,000 crore to print them.

In total, removing the old notes and replacing them with the new Rs. 500 and Rs. 2,000 notes will cost the central bank a total of at least Rs. 12,000 crore. This figure is likely to go up since additional security measures, which the new notes are set to have, will only add to the cost of printing.

By removing the Rs. 1,000 note, the government is doing away with the cheapest note to print in relation to the face value of the note.

Highest cost

The Rs. 3.17 it costs to print a Rs. 1,000 note is the highest in absolute terms across denominations, but it is the lowest when compared to the face value of the note.

For example, a Rs. 10 note costs only Rs. 0.48 to print, but that works out to 9.6 per cent of the face value of the note. Printing a Rs. 10 note costs 10 per cent of what that note is worth. This, for a Rs. 1,000 note, is 0.3 per cent.

2016: the impact

The first three days’ impact

The demonetisation of Re.500 and Re.1,000 notes was announced on Tuesday 8 Nov. 2016. It impact began to be felt the next day itself. The following items from The Times of India of 12 Nov 2016 chronicle the immediate, three-day impact of the action taken by the government.

ADVANCE PAYMENTS First, many employers have begun to pay their staff in advance -in some instances, salaries for the next one year -in cash. The tendency to pay employees in advance has been noticed in many private educational institutions, which mostly pay their staff in cash, said a source.These staffers will deposit this advance salary in their bank accounts.

Second, some traders are depositing their cash as business revenue to be shown as sales done before November 8 (the day of the ban) but payment received thereafter. Others, particularly wholesale traders, are reporting cash-in-hand in their ledgers to legitimise unaccounted for cash, and having it deposited at a later date.

BANKS SBI gets one month's deposits in one day

Demonetisation: Banks Get Rs 60K Cr In 2 Days

Banks have received nearly Rs 60,000 crore in deposits following the withdrawal of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 currency notes. SBI alone has raised about Rs 39,677 crore in deposits following the withdrawal of high denomination notes. Bankers expect the surge in deposits to bring down interest rates.

“We have received deposits of Rs 11,000 crore in savings accounts in one day .Normally , it takes a month to mobilise Rs 8,000 crore of savings deposits,“ said SBI chairman Arundhati Bhattacharya, while announcing the results on Friday afternoon.

At the end of the day , the bank said that the collections on Friday amounted to Rs 17,527 crore on the back of Rs 22,150 crore on Thursday . For exchange, the country's largest bank received Rs 723 crore worth of notes on Thursday and another Rs 943 crore on Friday .

According to Bhattacharya, demonetisation tends to have a deflationary impact.Also, the surge in low-cost deposits will bring down the bank's cost of funds.

Taken together, both measures would help bring down interest rates. Before demonetisation, the public held around Rs 14 lakh crore in Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 currency notes. These notes have to be exchanged or deposited in banks and post offices.

CARS Delhi has seen about 70% dip in registration of new vehicles in the past three days. On average, 1,500 vehicles are registered every day in the city. This number has come down drastically since November 8.

Sources said dealers, who also register vehicles in Delhi, had reported a similar drop in the number of registrations. “Some registrations are taking place but the number is minuscule. Registrations have almost stopped in the 13 RTOs in the city ,“ added the official.

JAN DHAN Dead since birth, Jan Dhan a|cs now flush with cash

A large amount of cash has suddenly started flowing into previously inactive Jan Dhan accounts.

The Jan Dhan Yojana was launched in August 2014 with an aim to bring the poor into the fold of banking facilities, and empower them financially by encouraging savings, and easing loan delivery and direct cash transfer.

Accounts opened at the time but not used so far have overnight turned flush with funds. Many such accounts, which held only Re 1or Rs 2 till November 8, now have up to Rs 49,000, the upper limit for deposits that can be done without PAN cards.

A few bank officials told TOI on the condition of anonymity that many accountholders were possibly being exploited by middlemen or the rich to lend their accounts to park cash.

Ajay Agnihotri, manager of State Bank of India's Fatehabad Road branch in Agra, said, “There are around 15,000 Jan Dhan accounts at our branch, and 30% of the account-holders have deposited amounts of up to Rs 49,000 since Thursday (when banks reopened in the wake of the demonetisation announcement). We are quite sure that this percentage will go up in the coming days.“

Another bank official added, “In certain cases, we are quite sure that it is not their money . Gullible persons and those working on a contractual basis in factories are being used by their employers as well as middlemen. However, people should know that the government is tracking all the records and transactions.“

TOI was able to track a few account-holders used for this purpose. One of the victims, who had deposited Rs 49,000, said he was promised Rs 500 in return. He would have to return the rest of the money in some days.

“I was told that if I deposit this amount, my reputation in the bank will go up. The middleman also said he would help me financially in the future,“ he added.

LIQUOR vends from different parts of Delhi reported about 40% dip in sales.

MANDIS Cash low, mandis may close

Biz Slumps, Traders Want To Withdraw 50% Of Daily Sales

A crisis may soon erupt in the city with traders threatening to shut down the wholesale vegetable and fruit markets for a few days unless they are allowed to withdraw at least 50% of their daily sales from banks.

“We haven't been able to pay farmers and labourers for the past three days. Also, sales have suffered because retailers do not have cash to pay us. We have asked the government to allow us to withdraw 50% of our daily sales from banks or we will be forced to close down till the market stabilises,“ Kriplani said.

Business in the mandi slumped by almost 50% on Friday .

Sources said that on Friday several transporters refused to accept cash or cheques. “They said that as petrol pumps were not accepting cash, they would not be able to refuel,“ said a source. This problem was resolved by the evening after the government announced that petrol pumps would continue accepting notes of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 denomination for another 72 hours.

The problem in the mandi percolated down to the retail market where several vendors had trouble getting stock.While many said that they had taken goods on credit, they were unable to make sufficient sales as customers had run out of cash.

REAL ESTATE: There was a significant decline in the revenue department's collections from registration of property sale deeds in Delhi. Data show that across 11 districts, a total of 674 documents were registered on November 8, resulting in a collection of Rs 6.73 crore. This was the day when the demonetisation was announced. A day later, the collections dipped to nearly half at Rs 3.89 crore.

In stark contrast, the daily revenue collection from registration of documents around Diwali ranged from Rs 5.10 crore to Rs 8.41 crore. On November 4, as many as 970 documents were received and 918 registered. On November 7, too, 842 documents were registered. Since then, it had been all downhill, said officials.

SHOPS Shops down shutters as purchasing power hit

DELHI: Markets across the city continued to wear a deserted look with some even observing a total shutdown on Friday . While traders' associations attribute this to loss of business due to the liquidity crunch, some shop owners admit that the news about income tax raids has created panic among people.

Nearly 80% of shops in the Walled City , which mostly deal in cash, downed their shutters. Naresh Khanna, president of jewellery association of Dariba Kalan market, said there was panic among people and no one was willing to visit the markets. “The government has ruined the wedding season. We decided to shut our shops as there is no business,“ added Khanna.

The Naxalite strategy: Jan Dhan to launder notes

See also Naxalism/ Maoism: India

Jaideep Deogharia, Jan Dhan a|cs to help Maoists convert levy, Nov 11 2016 : The Times of India

The CPI (Maoist) zonal and special area committee (SAC), which collects levies in cash for the organisation's daily functioning, is not worried about the sudden demonetisation of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 currency notes.The Jan Dhan accounts of villagers in rural Jharkhand will bail out the rebels by converting the “redundant“ currencies into usable instruments, they believe. Maoists who possess Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 currency notes in large numbers -collected from contractors, mining companies and industrialists as “levy“ -have issued instructions to their cadres to hold talks with the villagers and expedite a workable plan.They count on the villagers as supporters and hope the latter will deposit money in their Jan Dhan accounts for a commission and help them. Bihar-Jharkhand Special Area Committee (BJSAC) spokesperson Gopalji said the levy collected is handed over to the central committee which, in turn, allocates money to different zonal and special area committees for their functioning. “Zonal and special area committees, in particular, do not have much in cash but the ban will create trouble unless the notes are exchanged,“ he said.