Delhi: Economy

Contents |

Growth: 2001-2011

Delhi gobbled up villages to grow

One Third Of Population In Urbanized Villages In Lal Dora Areas That Doubled In Past Decade

Rukmini Shrinivasan TIG 2013/06/12

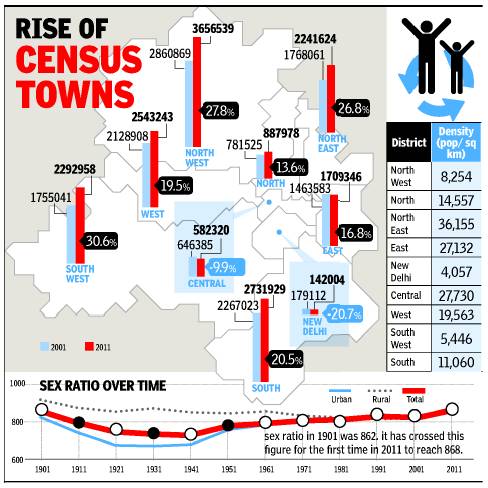

New Delhi: The capital’s growth in the decade 2001-11 has overwhelmingly come from the city swallowing up rural areas, newly released census data shows. The number of census towns—essentially newly urbanized villages in the lal dora areas—nearly doubled over the last decade, taking the proportion of Delhi’s residents who live in these areas to an unprecedented third of the population.

Varsha Joshi, director of census operations for Delhi, released the Primary Census Abstract for the National Capital Territory of Delhi on Tuesday. PCA gives the final population totals for every ward and village in NCT, as well as their literacy rates and sex ratios; provisional numbers were released last year.

The census redefines a village as a census town when it is densely populated and over three-quarters of its men work outside agriculture. In 2011, India had 3,894 census towns, home to half its urban population. The new numbers show that nearly 50 lakh people in Delhi, of a total population of 1.6 crore, live in census towns, which range in size from the 1,178-strong Shakarpur Baramad in east Delhi to Karawal Nagar, home to 2.24 lakh people, in north-east Delhi.

In 2001, 25 lakh people lived in Delhi’s census towns and they formed 18% of the population. By 2011, the proportion of rural residents in NCT had shrunk to just 2.5%. Simultaneously, the number of census nearly doubled to 110. About 30% of the NCT’s population now lives in these census towns. In fact, of the 29 lakh people added to Delhi’s population in the last decade, 24 lakh were added in census towns alone.

Of Delhi’s nine districts, north-west has seen the highest growth in population (22%) and is Delhi’s most populated district with over 36 lakh residents. Over 35% of the north-west lives in census towns. Saraswati Vihar in north-west Delhi has the highest population of any of the NCT’s 27 sub-divisions. Both New Delhi and central Delhi on the other hand have fewer residents than in 2001.

Population numbers at the ward level show that just four years after delimitation, the population of different wards varies wildly, from 1.5 lakh residents in Hastsal to just 15,000 in Kashmere Gate, which saw large-scale slum demolitions.

As The Times of India had reported earlier, Delhi has India’s lowest female workforce participation rate, with just 8.25 lakh women or roughly 10% reporting as workers. In contrast, there are 48 lakh male workers; over half of males across ages in the NCT report as workers. Seelampur reports the lowest female workforce participation of just over 5%. “We took a lot of steps to improve enumeration of women workers, but this is still what we have found. It’s really something we are worried about,” Joshi said. Over 95% of Delhi’s workers are ‘main workers’, meaning that they do economically productive work for over six months in the year. Connaught Place has the highest work participation rates for both men and women.

The proportion of scheduled castes in Delhi’s population has remained nearly constant at 16.75%.

Sex ratio in Delhi: 2011

In 2011 Delhi had a higher proportion of women in its population than it has had at any time in over a century. The sex ratio – number of females of all ages for every 1,000 males – was 868 in 2011, the first time that it has crossed 862, the previous highest set way back in 1901. This change has taken place despite no significant improvements in Delhi’s child sex ratio which stands at 871 girls for every 1,000 boys between the ages of 0 and 6. The figure for 2001 was only marginally lower at 868. There seemed to be more family migration taking place and fewer single male migrants, Varsha Joshi, director of census operations for Delhi, had said earlier. That could partly explain the dramatic improvement in the overall sex ratio between 2001, when it was 821, and 2011.

Jobs, Economy Growing Faster Than National Avg

TIMES NEWS NETWORK

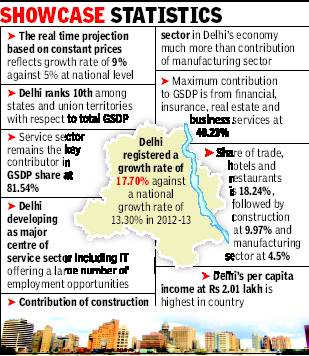

2013: Services once again accounted for the largest share (81.54%) of Delhi’s state gross domestic product (GSDP) in the previous financial year, according to the report “E s t i m a t e s o f S t a t e D o m e s t i c P r o d - u c t — 2 0 1 2 - 1 3 o f D e l h i ” compiled by the Directorate of Economics & Statistics .

The report said Delhi has become the most attractive city for youths seeking work across the country, thanks to her government’s pragmatic economic policies. It added that the 17.7% growth in Delhi’s GSDP, compared to 13.3% at the national level, reflects the city’s economic health. After accounting for inflation, the growth amounts to 9%, compared to 5% at the national level. The report states that Delhi’s GSDP is the 10th largest in India.

The predominance of services in Delhi’s economy is in line with the city’s industrial policy that promotes non-polluting units. The secondary sector (industry) contributes 17.69% and the primary sector (agriculture) 0.77% of the GSDP, the report states.

Finance, insurance, real estate and business services make up 40.23% of the service pie, followed by trade, hotels and restaurants with 18.24%, and construction (9.97%). Large-scale construction across the city has increased the contribution of this sector.

The report states that the ratio of Delhi’s GSDP to the all-India GDP at both current and constant prices has increased steadily. Delhi contributes 3.87% of the national GDP with only 1.42% of the population. Since 1998-99, Delhi’s GSDP has risen from Rs 53,226 crore to Rs 3.65 lakh crore—an increase of 687% “during the last 14 years of the present government,” a statement from the CM’s office stated.

Per capita income in Delhi is Rs 2.01 lakh compared to Rs 1.73 lakh in 2011-12—an increase of 15.77%. It is three times the national average of Rs 68,747. Per capita income crossed the Rs 1 lakh mark in 2008-09, and increased to Rs 1.27 lakh in 2009-10. In 1998-99, it was only Rs 40,060.

Garbage

WASTE-LINE WORKOUT

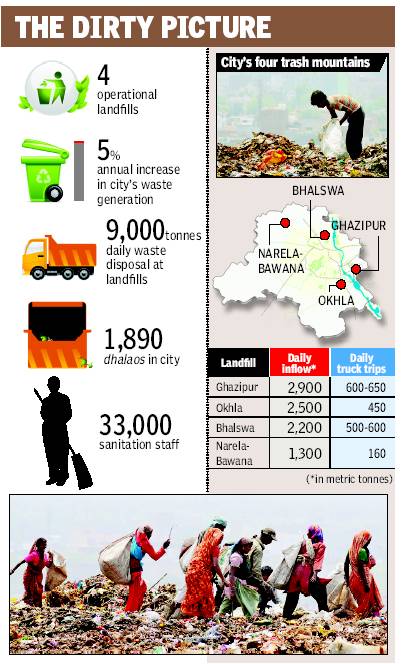

It takes a lot of effort to tuck away the 9,000 tonnes of waste Delhi throws out every day. Thousands of people and hundreds of machines are on the job round the clock but the challenge keeps growing

Risha Chitlangia | TNN The Times of India 2013/05/16

Like an army of slugs, some 220 small tippers and 1,000 rickshaw carts invade the streets of north Delhi at 7am every day to collect garbage. The hoot of a siren announces their arrival in a residential block, and in 10-15 minutes every doorstep is covered. By 3pm, 800 tonnes (roughly the weight of 20 Metro coaches) of household waste has been removed.

For four years now, that’s been the routine in 200 north Delhi colonies under Rohini and Civil Lines municipal zones. But elsewhere in the city, residents’ associations have made their own arrangements for garbage collection at the street level as the civic agencies only pick up garbage from dhalaos.

As the day wears on, the collected garbage is loaded on larger trucks and sent to landfills. Quietly, around 9,000 tonnes of urban waste is removed in a day. This includes not only household garbage but also silt from drains, construction waste and the dirt and trash swept up from streets. Street cleaning and landfill management are still handled by the municipal corporations but the movement of garbage to landfills now involves private concessionaires in two of the city’s three municipal districts.

LANDFILL MANAGEMENT

With land at a premium in Delhi, managing landfills is a crucial task. More so as the city’s waste output grows by 5% annually. Trucks strain to climb three of Delhi’s landfills—Ghazipur, Bhalswa and Okhla—that have crossed the 30-metre mark, but with 1,700 truckloads of waste to dispose of daily, these sites have to be kept going for a while at least. To ensure that trucks don’t skid off at the blind turns, the uneven tracks are regularly repaired.

At the Ghazipur landfill, garbage is dumped at different locations every day to maintain a uniform height. “We have no option but to go vertical as the site is surrounded by a fish market, a livestock market, a waste-to-energy plant and GAIL’s plant to trap gases from the landfill,’’ says an official.

The dumped garbage has to be levelled with bulldozers. Ghazipur has six but only one works now. R P Sharma, a bulldozer operator, spends eight hours levelling the waste. He has to keep a towel wrapped around his face while he works. “The work is very difficult. It’s 8-10 degrees warmer here than at the ground level. The stench of garbage and gases is nauseating.” Waste from the Ghazipur slaughter house is also dumped here.

Sharma needs 10-15 minutes to level each truckload. A six-inch layer of construction waste and silt is then spread over it to strengthen the ground. Meanwhile, scavengers pick out cardboard, plastic bottles and bags, glass bottles, etc to sell. They are not supposed to be at the landfill but officials say it is difficult to stop them.

Bhalswa landfill is better equipped. Five of its six bulldozers work round the clock to level 2,200 tonnes of waste daily. North corporation has turned a part of the landfill into a green area. But there is no provision for proper disposal of the leachate (liquid produced in rotting waste). “We have installed a large pipe through which the leachate flows into a drain,’’ says an official.

The South corporation’s landfill in Okhla is now saturated. It rises more than 40 metres above ground level and is used to dump only construction waste and rejects from Okhla’s waste-to-energy plant. “It can’t take much load. There is a risk of its collapsing, especially in the monsoon. A proposal has been sent to the Delhi government for acquiring neighbouring land. If we are not given the land, we might have to shut down this site,’’ says an official.

NEW TECHNIQUES

The corporations are looking at new ways to manage the waste. The erstwhile MCD had sanctioned three waste-to-energy plants, of which one is operational in Okhla. It processes close to 1,500 tonnes of waste daily. North corporation has developed a scientific landfill at Narela-Bawana with waste-to-energy and composting plants. Its composting plant processes 1,300 tonnes of waste. “The waste collected from Rohini and Civil Lines zones is dumped here. Earlier, we used to take it to the landfill but faced many problems. It is also cost-effective, compared to dumping at the landfill,’’ says Abhay Ranjan, head of collection and transportation, Ramky Environ Engineers, a private concessionaire hired by North corporation for its door-to-door collection project.

Mahinder Nagpal, leader of the House, North Corporation says, “DDA is not allotting new landfill sites and the existing ones have crossed the saturation level. Once the Narela-Bawana plant is fully operational, we can reduce the load on Bhalswa.”

UPHILL TASK

Three of the city’s four landfills now rise 30 metres above the ground and are becoming unmanageable

Reclaimed ground

The lush green lawns, special play area for kids and World Peace Stupa have made the 34-acre Millennium Indraprastha Park a popular picnic destination in the city. But the site used to be a landfill before it was developed in 2004