Defections (political): India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

History

1967- 2020

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Does anti-defection law need an overhaul, March 16, 2020: The Times of India

The worrying factor for democracy is that MLAs are happily courting disqualification or tendering resignations for a better deal in [a] new dispensation.

The Tenth Schedule, inserted in the Constitution in 1985 after bitter experiences of governments falling prey to defections of MLAs, is silent on this new resignation formula to destabilise governments.

The 1960s and 1970s political arena was marked by ‘Aya Rams and Gaya Rams’, the coinage credited to Haryana MLA Gaya Lal who changed his loyalty to parties thrice in a short span of time in 1967. Haryana had two other stalwarts in the defection game — Rao Birendra Singh and Bhajan Lal.

Bhajan Lal in 1980 had defected to Congress after Indira Gandhi returned to power post-Emergency. He along with his ministers and MLAs merged with Congress to remain chief minister. Probably that made Parliament in March 1985 to insert Tenth Schedule, which then had validated defection of onethird of MLAs of a party and merger of one party with another if two-thirds of MLAs of the merging party favoured it.

The Tenth Schedule gave the Speaker of Lok Sabha and assemblies unquestionable power in deciding petitions seeking disqualification of MLAs under the anti-defection law. This was challenged in the Supreme Court, which by a slender 3-2 majority in Kihoto Hollohan case (1992 Supp (2) SCC 651) ruled that Speakers, while deciding petitions under anti-defection law, exercised judicial powers akin to a tribunal and hence their decisions would be subject to scrutiny of HCs and the SC.

Since then, the SC has been called upon numerous times to decide the validity of Speakers’ decisions under the antidefection law, which indicated rampancy of defection and Tenth Schedule’s limited deterrence effect.

Finding split and merger concessions in the Tenth Schedule getting exploited repeatedly, the NDA government under Atal Bihari Vajapayee through Parliament effected the 91st Constitutional Amendment in 2003, which prohibited defections through split and merger. It also capped the number of ministers in a government as experience showed that the carrot of ministerial berths to engineer defections led to jumbosized council of ministers.

With the anti-defection law plugging exit routes for MLAs and given the mind-boggling cost of re-election, it was hoped that there would be political stability in governance after exploration of opportunities for postpoll alliances between parties.

Penning the minority opinion in Kihoto Hollohan judgment, Justice J S Verma had noticed that under Articles 103 and 192, disqualification of MPs/ MLAs was to be decided by the President/governor after consulting the Election Commission. Finding that Tenth Schedule vested disqualification powers with the Speaker, he had raised doubts about the impartiality of Speaker.

“Speaker being an authority within the House and his tenure being dependent on the will of the majority therein, likelihood of suspicion of bias could not be ruled out. The question as to disqualification of a member has adjudicatory disposition and, therefore, requires the decision to be rendered in consonance with the scheme for adjudication of disputes,” the minority opinion had said. A similar view on erosion of traditional impartiality attached to Speaker was expressed by the SC through Justice N V Ramana in a recent judgment in the case relating to disqualification of Karnataka rebel MLAs.

The limitations of anti-defection law were evident from the fact that 17 MLAs, who resigned/were disqualified by the Speaker for anti-party activities, sought re-election and 11 of them got re-elected. Ten of them got ministerial berths in the B S Yediyurappa government that was formed after the H D Kumaraswamy government collapsed.

The SC in the Karnataka rebel MLAs case had said, “His (Speaker’s) political affiliations cannot come in the way of adjudication (of disqualification petitions)… There is a growing trend of Speakers acting against the constitutional duty of being neutral. Additionally, political parties are indulging in horse-trading and corrupt practices, due to which citizens are denied stable governments. In these circumstances, Parliament is required to reconsider strengthening certain aspects of the Tenth Schedule, so that such undemocratic practices are discouraged.”

Probably, the solution lies in creating an independent authority to deal with disqualification of MPs and MLAs under the Tenth Schedule. Justice Verma in Hollohan judgment had said, “Tenure of the Speaker, who is the authority in the Tenth Schedule to decide this dispute, is dependent on the continuous support of the majority in the House and, therefore, he does not satisfy the requirement of such an independent adjudicatory authority; and his choice as the sole arbiter in the matter violates an essential attribute of the basic feature.”

The anti-defection law

Highlights

July 13, 2019: The Times of India

Karnataka political crisis: All about the anti-defection law

How anti-defection law came into force

- ‘Aaya Ram Gaya Ram’ was a phrase coined in 1967 after Haryana MLA, Gaya Lal, changed parties thrice in the same day.

- The anti-defection law sought to prevent such political defections which may be due to reward of office or similar consideration.

- The 10th Schedule was inserted in the Constitution in 1985 laying down the process by which legislators may be disqualified.

- A legislator is deemed to have defected if he either voluntarily gives up membership of his party or disobeys the directives of the party leadership on a vote.

When can a MLA be disqualified?

- If the member voluntarily gives up membership of the party on whose ticket s/he is elected.

- If the member votes or abstains from voting in the House contrary to any direction of his/her party.

- Disqualification may be avoided if the party leadership condones the vote or abstention within 15 days.

What happens if an MLA is disqualified?

- If a member of the current House (15th legislative assembly) is disqualified, it means s/he cannot contest any election to the 15th House. However, s/he can contest the next assembly election (to the 16th House). Also, Article 164 (1B) of the Constitution states a member who has been disqualified cannot be made a minister till the expiry of his or her term, or till s/he is re-elected.

- If an MLA is disqualified on conviction for certain offences, he will be disqualified for a period of six years under Section 8 of the Representation of People’s (RP) Act. But Section 8 (4) of the RP Act gives protection to MPs and MLAs as they can continue in office even after conviction if an appeal is filed within three months.

Time limit

The law does not specify a time-period for the presiding officer to decide on a disqualification plea.

Resignation vs disqualification

- If an MLA is disqualified, then s/he cannot be a minister in the new dispensation without being re-elected.

- However, if an MLA resigns s/he can be inducted as a minister and get elected to either House of the legislature within six months.

Some misconceptions clarified

PDT ACHARY, June 26, 2022: The Times of India

But a close reading of the original law on defection, namely the 10th Schedule of the Constitution, shows that there are provisions most people have conveniently forgotten about in their euphoria. It is therefore necessary to turn our attention to these key provisions of the law on defection which came into force in 1985. Under the 10th Schedule, if a member of a legislative house belonging to a party voluntarily gives up the membership of his or her party or votes against the whip issued by that party in the house, he or she is liable to be disqualified. But the law carved out two exceptions under which a member could escape disqualification. One exception was in relation to a split in the original political party, resulting in one third of the legislators moving out and forming a separate group. In such a situation that group was not liable to be disqualified. But because this exception was greatly misused by politicians (remember the ayaram-gayram culture), it was later removed by Parliament through an amendment. Even the first condition for a split, namely, that it has to occur in the original political party was ignored and the split in the legislature wing alone came to be counted. The second exception is with regard to merger. Under it, if a political party merges with another political party and two thirds of its legislators agree to such merger, they will not be disqualified. This is the exception which has been misused in all cases of defection that occurred during the past eight years or so. As had happened in the case of split, here too, the members take notice of only the number. They started acting on the assumption that all that is required under the law is for them to secure the two-third number and move out of their party. In all such cases, the Speakers who determine the defection cases, have, for obvious reasons, supported them. As it happened, all those legislators straightaway joined the ruling party. However, Para 4 of the 10th Schedule which contains this exception makes one thing clear. The merger shall be deemed to have taken place in the original political party only if not less than two thirds of the legislators agree to such a merger. The law is also clear on the point that the merger has to first take place between two original political parties. If no such merger takes place, the exception does not become applicable. However, in a recent judgment of Bombay High Court in Girish Chodankar vs Hon Speaker Goa legislative assembly, it was held that the merger of two-third of members of a legislature party with another party shall be deemed to be the merger of the original political parties. This judgment does not reflect the correct constitutional position as per the 10th Schedule. Nevertheless, the judgment too emphasises the fact that the two-thirds of the members of the legislature party have to merge with another party to escape disqualification. From this analysis of the legal provisions of the anti-defection law, two things become clear. One, the breakaway group of Sena rebels even with two-thirds of members cannot function as an independent group or party. Two, if there is no merger with the BJP or any other party, the exemption from disqualification does not apply and all become liable to be disqualified. The basic point of the 10th Schedule is to disqualify whoever leaves his party after being elected. It may be one member or it may be all the members. Of course, it is subject to the exception of merger.

The anti-defection law was enacted not to facilitate defection but to eliminate it. This is one cardinal fact which the legislators and the political class as a whole seem to have forgotten. That is the lesson the Maharashtra developments teach us once again. ■ The writer was secretary general, Lok Sabha

SC, 2019: discretion of Speaker should not be fettered

Dhananjay Mahapatra & Amit Anand Choudhary, July 18, 2019: The Times of India

Though the SC will decide later the key question of if rebel Karnataka MLAs have submitted their resignations prior to initiation of disqualification proceedings, it feels an interim order is urgently needed given the involvement of competing rights of parties in the litigation. “In these circumstances, the competing claims have to be balanced by an appropriate interim order, which according to us, should be to permit the speaker of the House to decide on the request for resignations by the 15 members of the House within such timeframe as the speaker may consider appropriate,”the SC said.

“We also take the view that in the present case, the discretion of the Speaker while deciding the above issue should not be fettered by any direction or observation of this court and the Speaker should be left free to decide the issue in accordance with Article 190 (of the Constitution)... The order of the speaker on the resignation issue, as and when passed, be placed before the court.”

The bench clarified, “Until further orders, the 15 members of the assembly ought not to be compelled to participate in the proceedings of the ongoing session of the House and an option should be given to them that they can take part in the said proceedings or opt to remain out of the same.” The order puts the ruling coalition in a quandary as it dispels the coercive element in the disqualification proceedings initiated by the speaker which could have annulled the effect of resignation of the 15 MLAs that reduces the ruling side to a minority.

Court judgements

1967-2014

Dhananjay Mahapatra, July 22, 2019: The Times of India

The seeds of legislators being allured to switch loyalties were sown in Indian politics in 1967. In half a century, the phenomenon has come to suffocate politics. It reminds one of what 19th century French diplomat, political scientist and historian Alexis de Tocqueville had prophesied for America: “There are many men of principle in both parties in America, but there is no party of principle.”

Till the 1960s and before its split, Congress was the rotund pillar of multi-party politics, inheriting the people’s goodwill for its contribution to the freedom struggle. In 1967, as many as 16 states went to polls. Congress could not cross the majority mark in eight and began a culture of throwing baits for migratory legislators to defect.

During 1967-71, there were 142 defections in Parliament and 1,969 cases of shifting of loyalty by MLAs in assemblies. As many as 32 governments collapsed because of defections and 212 defectors were rewarded with ministerial positions (source: PRS Legislative Research).

Defections felled the first government in Haryana headed by Bhagwat Dayal Sharma. Congress defector Rao Birender Singh became chief minister in a coalition government formed by rebel Congress MLAs with the help of opposition parties. MLA Gaya Lal took ‘swinging loyalty’ to new heights by defecting thrice in a fortnight and political analyst coined the phrase ‘Aya Ram, Gaya Ram’. Half a century later, the nomenclature has changed to ‘horse-trading’.

Defections have always given a handle to governors to poorly camouflage their whimsical decisions as constitutional duties to topple governments. Such actions of governors have been the basis of many memorable Supreme Court judgments — Kihoto Hollohan [1992 Supp (2) SCC 651], S R Bommai [1994 (3) SCC 1] and Rameshwar Prasad [2006 (2) SCC 1].

Though the SC always faulted governors’ actions in lending unconstitutional help in toppling of governments, it steadfastly refused to enter the ‘political thicket’ to determine what constituted ‘horse-trading’ or defections due to allurement. And, this probably emboldened ‘political pendulum’ MLAs to continue with impunity what their predecessors had done in the past.

In the Bommai case, the SC had said, “There cannot be any presumption of allurement or horse-trading only for the reason that some MLAs expressed the view which was opposed to the public posture of their leader and decided to support formation of government by the leader of another political party. Minority governments are not unknown. It is also not unknown that the governor, in a given circumstance, may not accept the claim to form the government, if satisfied that the party or the group staking claim would not be able to provide to the state a stable government. It is also not unknown that despite various differences of perception, the party, group or MLAs may still not opt to take a step which may lead to fall of the government for various reasons including their being not prepared to face the elections. These and many other imponderables can result in MLAs belonging to even different political parties to come together. It does not necessarily lead to assumption of allurement and horse-trading.”

As the SC did not, and could not, lay down what constitutes horse-trading, some leaders of political parties continued to do what they were best at — identify MLAs in rival political parties and lure them with money or ministerial berths. Should defectors and those with criminal antecedents deserve a berth in the council of ministers? The SC in Manoj Narula judgment [2014 (9) SCC 1] had said, “Democratic values survive and become successful where the people at large and the persons-in-charge of the institution are strictly guided by constitutional parameters without paving the path of deviancy and reflecting in action the primary concern to maintain institutional integrity and the requisite constitutional restraints.

“It can always be legitimately expected, regard being had to the role of a minister in the council of ministers and keeping in view the sanctity of oath he takes, the prime minister (or chief minister), while living up to the trust reposed in him, would consider not choosing a person with criminal antecedents against whom charges have been framed for heinous or serious criminal offences or charges of corruption to become a minister of the council of ministers. This is what the Constitution suggests and that is the constitutional expectation from the prime minister. Rest has to be left to the wisdom of the prime minister.”

MLAs who accept bribes to switch loyalty know that they, as public servants, are committing a crime under the Prevention of Corruption Act. Leaders who offer bribes to MLAs are also aware of their crime under the PC Act. And yet, leaders do not flinch in offering ministerial posts to defectors.

The fourth president of the US, James Madison, had once said, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to gover n men, neither exter nal nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself. A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.”

India’s first president Rajendra Prasad had agreed with B R Ambedkar to say this on November 26, 1949, “Whatever the Constitution may or may not provide, the welfare of the country will depend upon the way in which the country is administered. That will depend upon the men who administer it.”

The Karnataka political imbroglio, caused by ever familiar defections, offers an opportunity to the SC to think of auxiliary remedial measures, in addition to the antidefection law in the Tenth Schedule of Constitution, to maintain polity’s purity.

2019: SC on the rebel Congress-JD(S) MLAs of Karnataka

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Nov 14, 2019: The Times of India

From: Dhananjay Mahapatra, Nov 14, 2019: The Times of India

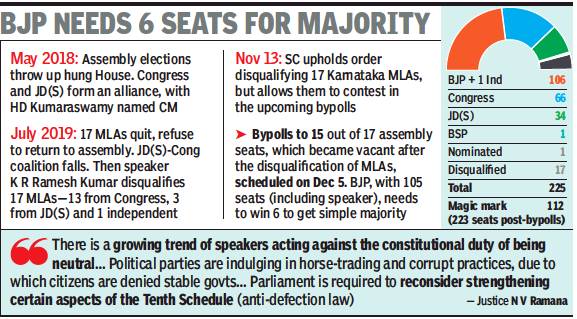

The Supreme Court upheld the Karnataka assembly speaker’s July decision to disqualify 17 rebel Congress-JD(S) MLAs, who brought down the H D Kumaraswamy government, but allowed them to contest bypolls from constituencies that fell vacant after their disqualification.

The unanimous verdict by a bench of Justices N V Ramana, Sanjiv Khanna and Krishna Murari, a rare judicial occurrence that pleased both sides, will have an important bearing on 15 bypolls and on whether the BJP government will acquire a majority in the 224-strong assembly. It enjoys the support of 106 MLAs and will be required to win six of the seats to have a majority.

Rejecting the contention of the disqualified MLAs that their resignations inoculated them from the disqualification provided for under the anti-defection law, it said: “We do not agree with the submission of the petitioners that the disqualification proceedings cannot be continued if the resignations are tendered. Even if the resignation is tendered, the act resulting in disqualification arising prior to the resignation does not come to an end. The pending or impending disqualification action in the present case would not have been impacted by the submission of the resignation letter, considering the fact that the acts of disqualification in this case have arisen prior to the members resigning from the assembly.”

On the interplay of defection, resignation and disqualification which involved the case, the bench said, “There is no doubt the disqualification relates to the date when such act of defection takes place. The tendering of resignation does not have a bearing on the jurisdiction of the speaker.... the taint of disqualification does not vaporise on resignation, provided the defection has happened prior to the date of resignation.” It said the speaker does not have the power to either indicate the period for which a person is disqualified.

See also

The Constitution of India (issues)