Child Labour: India

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

=The extent of the problem= | =The extent of the problem= | ||

| − | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Gallery.aspx?id=13_12_2014_010_011_002&type=P&artUrl=STATOISTICS-NO-CHILDS-PLAY-13122014010011&eid=31808''The Times of India''] | + | ==2011-14: rehabilitation== |

| + | [[File: child.jpg|State-wise rehabilitation under National Child Labour Project Scheme, 2011-14; <br/> From: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Gallery.aspx?id=13_12_2014_010_011_002&type=P&artUrl=STATOISTICS-NO-CHILDS-PLAY-13122014010011&eid=31808 ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| − | + | '''See graphic''': | |

| + | |||

| + | ''State-wise rehabilitation under National Child Labour Project Scheme, 2011-14'' | ||

==2011== | ==2011== | ||

| Line 19: | Line 22: | ||

'' Child labour in India, 2011 '' | '' Child labour in India, 2011 '' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==2019: Rajasthan== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2019%2F07%2F30&entity=Ar01605&sk=E525CD16&mode=text Intishab Ali, July 30, 2019: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | “How much is he worth?” His father’s words still ring in Pannu’s head. Rs 30,000 a year was the going rate apparently for a boy his age and size — a scrawny 12-year-old who stood at four feet then. As his father pocketed the advance that the middleman had brought along, Pannu didn’t know where he was going or if he would ever return. Some of his friends from nearby villages in Rajasthan’s Banswara district had disappeared overnight in the past few months, never to be seen again. Pannu was sent away with a gadariya (goat rearer) to Ujjain in Madhya Pradesh where he remained toiling for three years, often without food and sleep, until he was rescued by authorities last month. Gadariyas prefer to employ young children to look after the animals because they need little to eat and are obedient. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Extreme poverty has forced residents in tribal parts of Rajasthan — mainly Pratapgarh and Banswara districts — to send their children to work as child labourers for paltry sums of Rs 2,000 a month. The rocky landscape of the region renders agriculture a bleak possibility, with maize being the only viable crop here. Villages like Chundai and Hameerpur have never seen electricity, while nearest hospitals and schools are miles away and literacy is low. In Beh-Thenslavillage in Pratapgarh district, no one has studied beyond class 10. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Residents in these parts said that earlier they were getting employment under Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), but no work has been sanctioned under it in the past few years, plunging them into further penury. With no source of income, some families have been forced to send away children as young as six to work elsewhere. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the last 30 days, members of the child welfare committee at Banswara, under the department of women and child welfare, have rescued two more child labourers apart from Pannu. Eightyear-old Rohit was rescued from MP’s Dhar in June. Rohit was then brought to a care home in Banswara. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In nearby Pratapgarh district as well, two child labourers were rescued recently by Childline India, a non-gover nmental organisation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A team of Rajasthan State Commission for Protection of Child Rightsrecently surveyed the affected districts. Vijendra Singh, a member of the team, told TOI that they found presence of a network of middlemen aiding the illicit trade. | ||

| + | |||

| + | With over 8 lakh children engaged in child labour, Rajasthan is third among states where it is most prevalent. In Uttar Pradesh, 20 lakh children and 10 lakh kids in Bihar are engaged in manual work. Earlier this month, Santosh Kumar Gangwar, Union minister of state for labour and employment, had told the Lok Sabha that over three lakh child labourers were rescued in the last five years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But these are hardly stories of happy family reunions. In Pannu’s home in Chundai village, his mother has refused to take him in. “What is he supposed to do here? The authorities have put him in a shelter home where he gets food to eat and can probably go to school as well. What life can we give him here?” she said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some victims of child labour — exposed to abuse and exploitation for long periods — have started to exhibit symptoms similar to people with trauma disorders such as anxiety and insomnia. A TOI team that visited Beh-Thensla village found a boy crouching behind the bushes, some distance from his thatched house. The boy was rescued from Indore and brought home by Childline last month. His mother explained that Bablu runs to the fields whenever he sees someone approach the house. He returned after his mother’s repeated pleas but was cowering in fear for a long time. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Child rights activists said eradication of poverty was necessary to end reliance on child labour. Apart from enforcement of legislation, it is important to improve living standards and education of vulnerable children and their families. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (**Names of children have been changed) | ||

| + | |||

=See also= | =See also= | ||

| Line 29: | Line 59: | ||

CHILD LABOUR: INDIA]] | CHILD LABOUR: INDIA]] | ||

[[Category:India|L | [[Category:India|L | ||

| + | CHILD LABOUR: INDIA]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Crime|L CHILD LABOUR: INDIA | ||

| + | CHILD LABOUR: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|L CHILD LABOUR: INDIA | ||

CHILD LABOUR: INDIA]] | CHILD LABOUR: INDIA]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:34, 26 January 2021

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit] The extent of the problem

[edit] 2011-14: rehabilitation

From: The Times of India

See graphic:

State-wise rehabilitation under National Child Labour Project Scheme, 2011-14

[edit] 2011

From: Intishab Ali, July 30, 2019: The Times of India

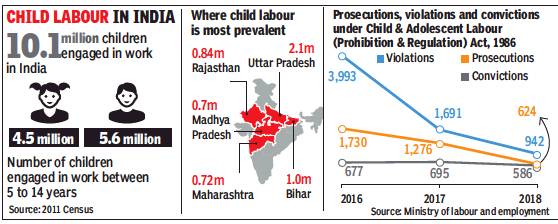

See graphic:

Child labour in India, 2011

[edit] 2019: Rajasthan

Intishab Ali, July 30, 2019: The Times of India

“How much is he worth?” His father’s words still ring in Pannu’s head. Rs 30,000 a year was the going rate apparently for a boy his age and size — a scrawny 12-year-old who stood at four feet then. As his father pocketed the advance that the middleman had brought along, Pannu didn’t know where he was going or if he would ever return. Some of his friends from nearby villages in Rajasthan’s Banswara district had disappeared overnight in the past few months, never to be seen again. Pannu was sent away with a gadariya (goat rearer) to Ujjain in Madhya Pradesh where he remained toiling for three years, often without food and sleep, until he was rescued by authorities last month. Gadariyas prefer to employ young children to look after the animals because they need little to eat and are obedient.

Extreme poverty has forced residents in tribal parts of Rajasthan — mainly Pratapgarh and Banswara districts — to send their children to work as child labourers for paltry sums of Rs 2,000 a month. The rocky landscape of the region renders agriculture a bleak possibility, with maize being the only viable crop here. Villages like Chundai and Hameerpur have never seen electricity, while nearest hospitals and schools are miles away and literacy is low. In Beh-Thenslavillage in Pratapgarh district, no one has studied beyond class 10.

Residents in these parts said that earlier they were getting employment under Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), but no work has been sanctioned under it in the past few years, plunging them into further penury. With no source of income, some families have been forced to send away children as young as six to work elsewhere.

In the last 30 days, members of the child welfare committee at Banswara, under the department of women and child welfare, have rescued two more child labourers apart from Pannu. Eightyear-old Rohit was rescued from MP’s Dhar in June. Rohit was then brought to a care home in Banswara.

In nearby Pratapgarh district as well, two child labourers were rescued recently by Childline India, a non-gover nmental organisation.

A team of Rajasthan State Commission for Protection of Child Rightsrecently surveyed the affected districts. Vijendra Singh, a member of the team, told TOI that they found presence of a network of middlemen aiding the illicit trade.

With over 8 lakh children engaged in child labour, Rajasthan is third among states where it is most prevalent. In Uttar Pradesh, 20 lakh children and 10 lakh kids in Bihar are engaged in manual work. Earlier this month, Santosh Kumar Gangwar, Union minister of state for labour and employment, had told the Lok Sabha that over three lakh child labourers were rescued in the last five years.

But these are hardly stories of happy family reunions. In Pannu’s home in Chundai village, his mother has refused to take him in. “What is he supposed to do here? The authorities have put him in a shelter home where he gets food to eat and can probably go to school as well. What life can we give him here?” she said.

Some victims of child labour — exposed to abuse and exploitation for long periods — have started to exhibit symptoms similar to people with trauma disorders such as anxiety and insomnia. A TOI team that visited Beh-Thensla village found a boy crouching behind the bushes, some distance from his thatched house. The boy was rescued from Indore and brought home by Childline last month. His mother explained that Bablu runs to the fields whenever he sees someone approach the house. He returned after his mother’s repeated pleas but was cowering in fear for a long time.

Child rights activists said eradication of poverty was necessary to end reliance on child labour. Apart from enforcement of legislation, it is important to improve living standards and education of vulnerable children and their families.

(**Names of children have been changed)