Corruption: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

The origins and causes of corruption

Time to Rock the Vote

Prem Shankar Jha Tehelka.com, 10 Sep 2011

Paying for running a democracy

Despite 15 parliamentary and over 300 state elections [till 2011], democracy has not empowered the people of India. Instead, it has created a predatory ruling class that has preyed upon them.

Dissatisfaction with democracy is not new. The Nehru years were undoubtedly years of empowerment: the government was honest; it drew up grand plans for ending poverty, and the people believed in them. But the euphoria did not last. Disillusionment first revealed itself in the so-called protest vote — a clear pattern seen in the 1967 General Elections and Congress defeats in state legislatures being associated with a sharp rise in the voter turnout.

Dissatisfaction became endemic in the 1980s. Voters threw out incumbent governments so regularly that this came to be known as the ‘anti-incumbency factor’ — a classic case of calling a symptom a disease. ==Origins: Two flaws in the Constitution CORRUPTION, EXTORTION, criminalisation, the black trishool that has poisoned the heart of the Indian State, can only be eradicated if its roots are fully exposed. The origins of all three can be traced to two deep flaws in the Constitution India adopted in 1950. The first is the omission of a system for meeting the cost of running a democracy, i.e. the entire process of selecting and then electing the peoples’ representatives. The second is the failure to enact provisions that would convert a bureaucracy that had been schooled over a century into believing that its function was to rule the people into its servants.

Meeting the cost of running a democracy

The first arose from an unthinking emulation of the British practice. What the members of the Constituent Assembly forgot was that whereas the average British constituency was 375 sq km in size, and today has an electorate of 60,000, the average parliamentary constituency in India is 6,000 sq km in size and has 1.2 million voters. In Britain, a candidate for Parliament can therefore get into his car every morning, visit two or three towns and villages, and return home every night. But in its Indian counterpart, the typical constituency has more than a thousand villages. To man its 1,000-1,200 polling booths, every serious candidate has to employ at least 8,000 persons on polling day. The cost is, quite simply, enormous. The failure of the Constituent Assembly to understand how this difference in size made it impossible to copy the British model in India was surprising, to say the least.

The oversight could have been remedied with a constitutional amendment at a later date, but instead, in 1967, Indira Gandhi took the country in the opposite direction and choked off the only legitimate source of funds that had sprung up in the intervening years. This was the donations from corporations that all parties, except the Communists, had begun to depend upon.

Gandhi took this decision weeks after the Congress party came close to defeat in the General Election of 1967. Not only did its tally in the Lok Sabha fall from 353 to 282 — only 10 more than what it needed for a majority — but for the first time, it also lost the Assembly elections in six major states. It first repealed the tax concessions on donations to political parties and followed it up three years later with a complete ban on company donations to political parties. But while choking the political system’s main source of funds, she deliberately did not create an alternative.

She did this because her purpose was not, as her party claimed, to reduce the influence of big business on policy-making. The second Industrial Policy Resolution of 1956 had already done this. It was to cripple a rising threat from the right by depriving it of funds. In 1967, the pro-market Swatantra Party, formed by C Rajagopalachari in 1961, and the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS) had fought the elections jointly and become a serious threat to the Congress in three states. These were Madhya Pradesh, where the BJS won 78 out of the 296 seats, Gujarat, where the Swatantra Party won 66 out of 168 seats, and Rajasthan, where, by winning 72 seats, they succeeded in reducing the Congress to a minority.

Indira Gandhi’s decision to ban corporate donations to political parties in 1967 took the country in the opposite direction from the one it had taken under Nehru

More than their share of the seats, the Congress feared their much larger share of the vote, for this threatened to turn them into a magnet for the then numerous smaller parties and independents. A two-party, or at least two-coalition, political system, therefore, seemed on the point of being born, but the threat that a second national party could pose to the Congress was too much for its leaders to stomach. It therefore, knowingly, passed a law designed to starve the Opposition of funds that only it, by virtue of being in power, could flout with impunity.

Birth Of The Predator State

The ban on company donations closed the only honest, open and transparent avenue for raising funds to fight elections, which had come into being since Independence. Like Solomon Bandaranaike’s Sinhala-only language policy of 1956, it was entirely opportunistic. And as in Sri Lanka, the harm it has done is beyond measure. For it has deprived all political parties, including the Congress, of the option of remaining honest. It therefore, opened the gates for the entry of crime and black money into politics.

Over almost half a century, we have become familiar with the corruption and extortion that this has bred. But few understand the deadly impact that it has had on Indian politics. Its immediate effect was to all but destroy the centrist Opposition in Indian politics, and strengthen its ideological extremes. The Swatantra, being the most dependent on funds from the corporate sector, simply threw in the towel: most of its members merged with the Jana Sangh. The two socialist parties, the Praja Socialist Party (PSP) and the Samyukta Socialist Party (SSP), weakened rapidly, merged, then joined the Janata Party in 1977 and finally, disappeared altogether. Their place was taken by a host of caste and ethnicity-based political parties that we are familiar with today.

Only the Jana Sangh and the two Communist parties survived relatively unscathed. By the late ’70s, therefore, the dream that India would one day develop a bipolar political system similar to that of Britain had vanished.

A second, more serious effect, has been to stifle intra-party democracy. The ban on company donations made it harder even for the Congress to raise funds, for its managers had to replace a relatively small and stable cadre of large donors with a much larger number of widely dispersed donors, who were prepared to contribute small sums in cash. Over time, the sheer difficulty of doing this every few years has made them extremely reluctant to disturb a financing network once it had been established. In 80 percent of the constituencies, these networks are inevitably local. All the favour-swapping that has to be made to establish them centres on gaining the favour of not only the party in power, but more specifically, the candidate who represents it in the legislature. This is the origin of clientelist politics.

The actual deals are struck by self-appointed lieutenants, who give candidates the elbow room necessary to modify, or get out of, conflicting commitments. Once a network is established, and especially once it has succeeded in getting its candidate elected, the lieutenants have the most powerful of interests in making sure that it is not threatened by a rival. New entrants into politics determined to change things stand little chance of breaking these clientelist networks. Thus, the more Indian democracy has matured, the more it has succeeded in shutting new people out of politics unless they too are prepared to become a part of the existing clientelist networks.

Princelings

A corollary to this has been the rise of the so-called ‘princelings’ — a second generation of leaders in Indian politics who have inherited and not earned their constituencies. In western democracies, when a long-term member of Parliament, National Assembly or Congress dies, the party almost always chooses a successor on the basis of his or her standing in the constituency. In India, by contrast, the death of a senior politician triggers a rush by the operators of his clientelist network (who have all been inducted into the party by then) to Delhi or the state capital to make sure that there is no contest for the vacant seat, and that the dead leader’s wife, son or daughter is nominated to take the parent’s place. They do this because, sentiment apart, this is the one way of making sure that the clientelist network will not be disturbed. While some ‘princelings’ regularly capture headlines, they make up only a small visible fringe of the tribe. A study by Patrick French of the composition of the 2009 Lok Sabha showed 156 MPs (28.5 percent), including 78 from the Congress (37.5 percent), were selected as candidates because of their family connections. What is still more significant is the preponderance of princelings in the younger members. What is more, French found that “nearly half of all MPs aged 50 or under, are hereditary — selected to contest a seat primarily because they are the children of politicians. Thirty-three of the youngest 38 MPs and every Congress MP under the age of 35 entered Parliament because of their birth.

These figures are disturbing not because of their character and ability, which is much higher than the average, but because, as French concluded: “If you do not come from an established ruling family, you have almost no chance of progressing in national politics, unless you join an ideological party such as the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) or the Communist Party of India (Marxist), where lineage is not important.”

Weakening of national leaderships

A third, unforeseen consequence has been the weakening of national leaderships of the main, non-ideological parties. In this too, the Congress was the first sufferer. When donations were legal, the money used to come directly to the president or treasurer of the political party. This ensured that the reins of financial power remained in the hands of its leaders whom the public recognised and could hold accountable for the way it was collected and spent. But once money began to be raised clandestinely, financial power slipped into the hands of anonymous, unaccountable and, more often than not, unsavoury characters. What is more, control over these new money collectors passed more and more out of the hands of the central party leaders into those of the leaders in the states.

Over time, the price that fundraisers demanded kept growing and, with it, the power of the elected leaders to choose candidates or determine policy, declined. One of the first victims of the change was Indira Gandhi herself. Scholars have severely criticised the way in which she concentrated power within the Congress in her own hands during the Emergency, but in reality, this was a defensive action to stem a weakening of her control over the party that only she fully sensed. For by the mid ’70s, she had all but lost control of several charismatic Congress chief ministers, including HN Bahuguna in UP and VP Naik in Maharashtra. Both were able administrators, and Bahuguna in particular, had restored efficient governance in UP after a lapse of several years. The main reason why Gandhi felt obliged to withdraw her trust from them was that they were no longer obeying the Centre’s directives. In all, Gandhi changed the chief ministers in the Congress-ruled states no fewer than 15 times between 1975 and 1977. That she did this during the 21 months of the Emergency, when, in theory, she was at the peak of her powers, shows how much the Centre had been weakened by the changes that had occurred within the party.

The weakening of the central leadership of the Congress has reduced the capacity of the national leaders to take hard decisions in national interest. In 1967, Gandhi was able to overcome the resistance of a powerful regional chief minister in Assam, BP Chaliha, and separate Meghalaya from Assam. Sixteen years later, her inability to control the Punjab Congress precipitated the Khalistan insurgency in the state. Not only was the Punjab Congress responsible for the rise of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, whom it actively fostered in an attempt to break the Akali Party, but three meetings between Gandhi and Sant Longowal in 1983 failed to produce an agreement over four long-standing demands that, if conceded, would have stemmed the rise of separatism in Punjab. This was because she was unable to persuade the state Congress party’s leaders in Punjab (and Haryana), to endorse anything that would give the Akalis an edge over them in the next election. The country paid the price for her failure with 10 years of insurgency and 61,000 civilian lives. Two thirds of the victims were Sikhs.

Criminals in politics: India

The fourth consequence is the entry of criminals into politics. Members of the current Parliament (29 percent) are facing serious criminal charges including murder, arson, rape, kidnapping, dacoity and illegal possession of arms. In the current Bihar legislature, the ratio is 44 percent and in the recently elected West Bengal Assembly, it is 35.1 percent. To think that West Bengal is one of the most law-abiding states in the country!

The final act in the cementing together of the clientelist State and denying access to power to ‘outsiders’ was the establishment of the MPs and MLAs’ Local Area Development Scheme (MPLADS and MLALADS) under which they are allotted plan funds to spend on development projects in their constituencies at their discretion. On paper, this power is hedged with elaborate safeguards to prevent misuse, but in practice there is no effective monitoring of how much of the allocated money is spent on projects and how much finds its way back into the MP or MLA’s pocket. This scheme has completed the conversion of constituencies into zamindaris. But when the allocations for it was raised from Rs 2 crore to Rs 5 crore a year for each MP and from Rs 1 crore to Rs 2 crore for each MLA in the middle of the 2G scam furore, no one, not even Team Anna, voiced a single murmur of protest.

Economic Consequences

The economic consequences of the total denial of honest funding to political parties has been, if anything, even more devastating, for it has transformed what was intended to be a developmental State into a predatory one. This has taken place in four stages.

29 percent of the current MPs are facing serious criminal charges. The ratio is 44 percent in the Bihar legislature. In West Bengal, it is 35.1 percent

In the immediate aftermath of the ban on company donations, the Congress party’s fund managers also found themselves at a loss for where to raise the money to fight elections. In the 1971 Lok Sabha and 1972 Assembly elections, they therefore went back to the same companies and trade organisations from whom they used to accept tax-deductible cheques in the past, and demanded cash. Although most of them complied, they did so unwillingly. Raising money to meet electoral and administrative expenses therefore became more difficult than it had been before. But the gap was filled by owner-managers of small and medium-sized enterprises, traders and shopkeepers, moneylenders, and others in the informal sector with cash to exchange for entitlements and allocations from the government. This was the base of the shift of power from the central to state units of the Congress described earlier.

But small enterprises needed space to grow and rich farmers needed subsidies. The former played a significant role in providing the rationale for Gandhi’s second round of ‘socialist’ controls on ‘big’ business enacted between 1970 and 1973. The latter converted support prices in agriculture that were designed to protect farmers from loss into ‘procurement prices’ that regularly elevated the market price of cereals and ensured a steady and rising stream of profits for rich farmers. The political power of this ‘intermediate class’ not only caused a further fall in the GDP growth rate from 3.7 percent between 1956 and 1967 to 3.1 percent from 1967 to 1975, but prolonged the life of the command economy by another 15 years till 1991.

The defeat of the Congress in the ‘post-Emergency’ 1977 elections triggered something close to a financial collapse in the central Congress party, but left more than half of its state units relatively unaffected. This triggered the second phase of the development of the predatory state, for when the Congress returned to power in 1980, restoring the financial autonomy and pre-eminence of the central command of the party became one of Gandhi’s first preoccupations. It did this by institutionalising a system of commissions and kickbacks on foreign contracts, notably in infrastructure and defence.

Loss to the nation: opportunities foregone

Over four decades, the cost borne by the people, in terms of opportunities foregone, has been astronomical. Two examples, highlighted in the media at the time when they occurred, show how it has been paid. In the late ’70s, the Janata government had obtained World Bank financing for the first of a new generation of fertiliser plants based upon the natural gas from Bombay High to be set up at Thal-Vaishet, south of Mumbai. Based upon international bidding, the consultants employed by the World Bank had recommended that the contract be given to an American firm, CF Braun. But when the Congress returned to power in 1980, it began to negotiate independently with several firms, including Toyo Engineering of Japan and Haldor Topsoe of Denmark, a subsidiary of the state-owned Italian engineering giant, Snamprogetti. When the World Bank refused to reopen the bid, and pulled out of the project, the government went ahead nonetheless, beating the nationalist drum against foreign dictation, hinting at the World Bank’s subservience to the US government, and hence, partiality to CF Braun, proclaiming that it would finance the plant from its own (non-existent) foreign exchange resources.

Eventually, it awarded the contract not only for the Thal-Vaishet plant, but for four others, to Haldor Topsoe. At the time, it was common knowledge that the government had given the contract to Haldor Topsoe in exchange for a handsome kickback. Only later did the public come to know how much the country had to pay for that deal.

CF Braun had been chosen because of all the bidders, it had by far the most energy efficient technology and lowest overall manufacturing cost. Had the original project been implemented with all the safeguards of the World Bank, it would have set the benchmark for the entire future generation of gas-based plants. But it would, unfortunately, have made kickbacks on future projects much harder to obtain.

The award of a single contract for five plants without any international bidding led to an inflation of the capital costs of all the plants. To make matters worse, Haldor Topsoe’s ammonia making technology used 15 percent more energy per tonne of output. These two disadvantages ensured that these plants would never be able to produce urea at internationally competitive prices. The Thal-Vaishet project therefore created a much higher benchmark for capital costs in later plants. These and its higher energy costs had to be offset by subsidies. Since subsidies were designed to ensure a minimum return on capital invested, it ensured that the cost of all future plants would be ‘gold-plated’. Indian taxpayers have been paying the resulting, inflated, subsidies till this day.

Even while the Thal-Vaishet project was being renegotiated, the Ministry of Defence had begun a similar renegotiation of major defence contracts entered into by the Janata government. Two that were eventually reinstated at immensely higher prices (and much higher kickbacks) were the purchase of groundhugging long-range Jaguar fighter bombers for the Indian Air Force, and the Harrier vertical/short take-off aircraft for the Indian Navy from British companies.

Defence purchases

BUT THE country had to wait another five years to gain its first unequivocal understanding of the direction in which the political system had evolved. It got this from an exposé in the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter in 1987 of what came to be known as ‘The Bofors Deal’. And in much the same way as is happening now, the details only came to light because of then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi’s determination to clean up the system he had inherited. The investigations that followed the Swedish exposé revealed no fewer than three layers of kickbacks, totalling a mammoth 17 percent of the $1.3 billion contract. So great was public indignation over the deal and its aftermath that the revelation of yet another massive kickback, of 6 percent on the purchase of submarines from the German firm Howalds Deutsche-Werke, went virtually unnoticed.

The loss of money is, however, the least part of the harm that the institutionalisation of kickbacks has done. Kickbacks take time to negotiate. This has meant escalations in cost and a loss of valuable time. The last is unforgivable in defence contracts because it has left the country vulnerable for long periods while kickbacks are being struck. For instance, both Pakistan and India decided to equip their armies with 155 mm Howitzers at more or less the same time in the late ’70s. The Pakistan Army got its guns by the early ’80s. The Bofors deal was only finalised in 1985.

The need to arrange the kickbacks has led to an unhealthy centralisation of even routine procurement in the hands of the civilian staff of the Ministry of Defence. Today, senior armed forces officers openly lament that it takes an average three years for their requisitions to be met.

The institutionalisation of kickbacks has also meant that contracts have often not gone to the most qualified bidders because these have the least need to pay kickbacks in order to secure orders. This was the probable cause of the cancellation of the agreement with CF Braun.

But by far, its biggest effect has been to put the State up for sale. And in doing so, align it with the predators in society. For once it takes a bribe from a bidder, it makes itself a party to whatever the bribe-giver has to do to recover his ‘costs’. The State, thus, ceases to be the people’s watchdog.

The tendering system

This is the source of all the abuses that have crept into the tendering system — the omission of time schedules, the obfuscation of penalty clauses and, once the deal has been struck, the repeated modification of tenders to ensure that only the pre-determined bidder secures the contract. In addition, since the presence of independent consultants makes deal-making more difficult and fraught with risks, government departments have been found to be shy of employing them to plan and execute projects and have insisted on doing so themselves. This has not only removed the last remaining safeguard against graft but contributed to it.

State governments in particular, have taken advantage of this by developing a stratagem for extracting money from projects that only Indian ingenuity could have dreamt up: they chop up large projects into numerous smaller parts in the name of preserving competition, and invite separate tenders for each part. This allows ministers and bureaucrats to award contracts to small companies without the capital base, equipment or track record required to qualify for large projects, but willing to offer almost anything in return for getting a piece of the cake. Highway projects, and more recently a rash of tiny solar power projects, are the most obvious examples of such parsing for profit. The cost in terms of delays, inflation and shoddy work can be judged from the fact that the Golden Quadrilateral highway project, to link Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata and Chennai — started by former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in 1999 with the express purpose of providing a fiscal stimulus to the Indian economy after two years of recession — intended to be completed by 2004, is not even half complete in 2011. What is more, it is incomplete because there were unfinished portions in each and every section of the four highways! By contrast, Chinese companies have built 1,000 km of four-lane highways that measure up to European specifications in Kenya, and another 500 km of high-grade two-lane roads in just three years.

In the three decades or more, since kickbacks became the norm for financing political parties, these practices have spread to every corner of the country and every level of its government. Today, there is hardly a contract from the purchase of a new generation of Main Battle Tank to the construction of a rural road, which is not being preyed upon to extract money. Over the years, bureaucrats at every level, from the secretariats in New Delhi to Block Development Offices in each sub-division, have learnt that they can do with even greater impunity for themselves what their political bosses want them to do for their parties.

Ban on company donations lifted: 2003

Economic liberalisation in 1991 ushered in the third phase of development of the predator-clientelist State. The ban on company donations was finally lifted in 2003, but by then the need for funds far outstripped what industrialists, in the new, fiercely competitive economy, with its vastly reduced scope for favour-swapping, were prepared to pay.

According to a recent study by Indira Rajaraman in 2009-10, corporates, large and small, donated only Rs 130 crore to political parties. But industrialists have found more direct ways of influencing government decisions: they now just buy the concerned decision-makers. This is what the spate of scams in the 1990s and 2000s has shown.

The fourth and final stage of development of the mature clientelist State occurred when coalition rule at the Centre became the rule. Look at all the five governments formed since 1996 and you will find that while the ‘national’ party, be it the Congress or the BJP, has retained the ‘power’ portfolios — defence, home, external affairs and the prime ministerships, all but a few of the ‘money’ portfolios have been taken by its regional coalition partners. That is the root of the 2G scam. But the 2G scam is only an extreme case of what is now everyday, routine ‘business’.

[We are] indulging in wishful thinking if it believed that even the Lokpal of [our] dreams will make more than a dent in this awesome edifice of corrupt power. Nothing will change till political parties are once more freed from the need to break the law to stay in business and given the option to be honest once again. The only way to do this is to start a very large State fund for financing the electoral expenses of recognised political parties. This requires a much-strengthened Election Commission with a powerful auditing wing, and the adoption of strict and transparent criteria for awarding recognition to political parties. Other reforms can be built upon this foundation. But without it, all the rest will fail.

Mr Prem Shankar Jha, as a top-rung journalist, has had a ringside view of Indian governance.

premjha@airtelmail.in

Corruption: a ‘fact of life’ in India-US embassy

From the archives of The Times of India

New Delhi: The US embassy in July 1976 said corruption in India was a “cultural/political/economic fact of life”, and that it was not a Western import but historically a local phenomenon. It called the Congress party India's "united givers fund”. “It is impossible in any single message to give a description of the extent and modalities of corruption in India. Entire books have been written on this subject and there is little doubt but that these only dealt with the tip of the iceberg. It should be added that corruption is not a phenomenon which was brought to India by the West. Kautilya, the ancient philosopher, in his treaties Arthasastra refers to various kinds of corruption and prescribes corresponding punishments.” The cable said corruption was not confined to the business or political world. “Hindu and other religious shrines in India have long been known for their corrupt practices,” the cable said.

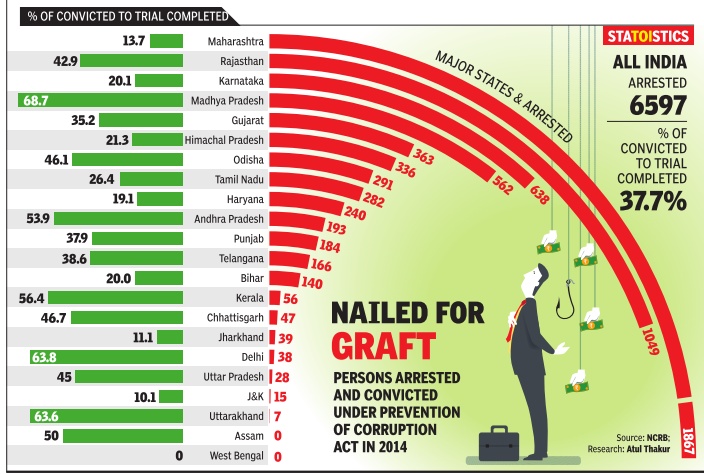

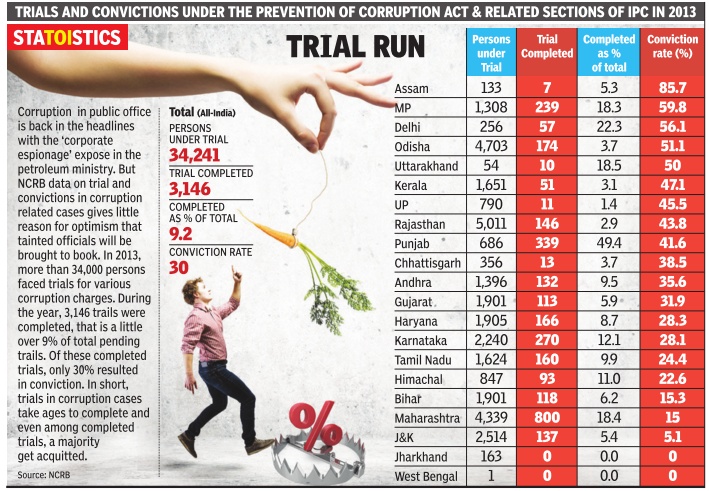

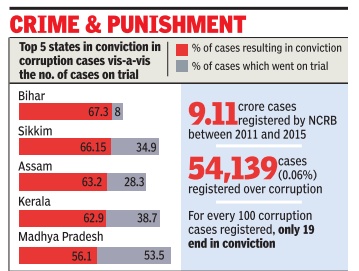

2001-15: conviction rate, state-wise

The Times of India, December 18, 2016

Himanshi Dhawan

India's graft war lacks `conviction'

In 15 Years, 5 States Saw Zero Jailed For Corruption, 3 Recorded 100% Acquittals

India appears to be fighting a losing battle against corruption. Not only the number of corruption cases registered stand at an abysmal 0.06% of total crime in the 15 years from 2001 to 2015, five states including West Bengal have not registered a single conviction. Trial has been completed only in half the cases and three states including Goa have a record of 100% acquittal.

These are just some of the findings of a study by Com monwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) based on NCRB data over 2001-2015. Analysis of NCRB data from 2001-2015 shows that a total of 54,139 corruption cases as compared to a total of 9.11crore offences were registered across the 29 States and seven Union Territories (UTs). Incidentally , during this period, people filed more than double that number (1,16,010) of reports about being required to pay bribes, on the popular website -I Paid a Bribe.

While 54,139 cases were registered, trial was completed in 55.26% (29,920) cases. In other cases the accused were discharged or the FIR was quashed or the case was simply not put up for trial or the trial was still going on.

Shockingly , despite several cases going up for trial, no convictions have been reported from states such as Bengal, Goa, Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura and Meghalaya. In Manipur, only one case is said to have yielded a conviction during this 15-year period.

CHRI report said Kerala clocked the highest conviction rate among states that registered a large number of cases as a proportion of cases sent for trial, at 62.95%. In terms of absolute numbers, Maharashtra topped the list of cases ending in conviction at 1,592 against 6,399 cases that went up for trial (24.87%).That means as a proportion of total registered cases, barely 18% ended in conviction.

From 2001-2015, trials involving 43,394 individuals were completed across the 28 states (excluding Himachal and seven UTs.) About 68% (29,591) of the accused were acquitted during this 15-year period (excluding Himachal). That is, 31.81% (13,803) of the accused were found guilty by courts.

In states like Goa, Manipur and Tripura acquittals were 100% while almost 90% of the accused were acquitted in J&K.In Andaman & Nicobar the trial was completed in relation to one accused during this 15-year period resulting in acquittal. Nagaland is the only state that bucked this trend with convictions of more than 90% of the accused. In all, 438 accused were convicted. Of these, 404 were convicted in 2014.In Assam also, convictions were much higher (70%), despite fewer cases going up to and completing trial.

The NCRB has registered more than 5 lakh (5,01,852) cases of murder. In comparison, only 54,139 cases of corruption were registered during the same period. In other words, for 10 murders registered, only one case of corruption was registered across the country .

At the same time, 5.87 lakh cases of kidnapping and abduction were reported in the country , that is for every 11cases of kidnapping or abduction, only one case of graft was registered. From 20012015, the NCRB reported the registration of 3.54 lakh (3,54,453) cases of robbery, or six robberies registered for only one case of corruption.

The Global Corruption Barometer, 2013

Graft in India twice the global average

Kounteya Sinha TNN 2013/07/10

London: Corruption in India has reached an all-time high with rates being exactly double of the global prevalence. Globally, 27% people say they paid bribes when accessing public services and institutions in the last year.

In India, however, the number of people who did the same was 54%. Political parties have been found to be the most corrupt institution in India with a corruption rate as high as 4.4 on a scale of 5 (1 being the least corrupt and 5 highest).

The highest amount of bribe however was collected by the police — 62% followed by to those involved in registry and permit (61%), educational institutions (48%), land services (38%). India’s judiciary has also been found guilty — 36% involved in bribes. Cynicism about a corruption free future is widespread among Indians with 45% saying they don’t think common man can make a difference.

On the other hand, around 34% people (1 in 3) said they wouldn’t report corruption if they face it. These are the findings of the Global Corruption Barometer 2013 — a survey of 1.14 lakh people in 107 countries released on Tuesday.

The index found that corruption is widespread globally, with 27% of respondents (1 in 4 people) having paid a bribe when accessing public services and institutions in the last 12 months, revealing no improvement from previous surveys. More than one person in two thinks corruption has worsened in the last two years. The police and the judiciary were seen as the two most bribery prone globally.

Transparency International, 2014

India less corrupt than China: Study TIMES NEWS NETWORK The Times of India Dec 04 2014

But Still Ranks With Burkina Faso, Benin

For the first time in 18 years, India ranks as less corrupt than China in the annual corruption survey by global watchdog Transparency International.

In its annual survey of 175 countries, India ranks an otherwise depressing 85th, but has improved in the index, jumping 10 places.

China, on the other hand, has fallen 20 places to rank 100th despite Chinese president Xi Jinping unleashing a massive campaign against corruption, arresting a number of high profile political and military leaders. While India and China were at more or less similar levels in 2006-07, this is the first time since the rankings started in 1996 that India is perceived to be less corrupt than China. The Corruption Perception Index is compiled by experts like banking institutions, big companies and other organizations based on their view of corruption in the public sector. Transparency International's annual report measures perceptions of corruption using a scale where 100 is cleanest and 0 most corrupt. India's score moved up to 38 from 36. Despite a slightly better showing by India, its contemporaries on the index are countries like Burkina Faso and Benin, nothing to write home about.

The Berlin-based organi zation published its 2014 Corruption Perceptions Index of 175 countries on Wednesday .Turkey and China showed the greatest drops in the index.

India's perception improvement is attributed to a heightened awareness and public antipathy to corruption from the time Anna Hazare began his agitation in 2012. This was succeeded by the first ever Lokpal Bill being passed in parliament. India's reputation has also been burnished somewhat by the pending anti-corruption bills wending their way through Parliament. Corruption was a major plank in the election campaign in the recently concluded general elections, a central part of BJP's pitch. Even Arvind Kejriwal's short-lived government in Delhi was premised on an anti-graft platform.

The top performer is Denmark at 92. In a statement, Transparency International said it is campaigning for countries to adopt a procedure called Unmask the Corrupt, urging the EU, US and G20 countries to follow Denmark's lead and create public registers that would make clear who really controls, or is the beneficial owner, of every company .

Government: Most corrupt departments

2013-14: petroleum, UD, steel, telecom

The Times of India, Aug 04 2015

`82% rise in graft plaints in a yr'

Grievances up 64k in 2014 as compared to 35k in 2013: CVC

The Central Vigilance Commission received an unprecedented 64,000 corruption complaints last year--a jump of 82% from the preceding year. In its annual report for 2014 laid before Parliament, the CVC said the maximum number of complaints about alleged corruption was received against railways employees. Despite the manifold increase in the volume of work being handled by the commission, there has been no increase in the staff strength.“It is for the first time that the commission had received such a high number of corruption complaints,“ a senior CVC official said. Of the total complaints received, 36,115 were vague or unverifiable, 758 were anonymous or pseudonymous and 24,012 were for officials not under CVC. There were 1,214 verifiable complaints which were sent for inquiry or investigation to chief vigilance officers (CVOs) who act as a distant arm of the CVC and CBI.

About 45,713 complaints of corruption were received by the CVOs against government employees. Of these, 32,054 were disposed and 13,659 were pending. A total of 6,499 complaints were pending for more than six months, it said.

A total of 3,378 corruption complaints were received against officials working in the ministry of petroleum and natural gas, 2,917 against employees working under urban development, 1,494 against those in steel ministry and 1,303 against department of telecommunications employees, the annual report said. There was a vacancy of 58 employees, as against the sanctioned strength of 296 in CVC, the annual report said. The CVC tendered advices in 5,867 cases during 2014.

2014: Delhi most corrupt UT

The Times of India, Aug 20 2015

Delhi led UTs in corruption cases

Nitisha Kashyap

Delhi Police had to deal with many cases of corruption by government officials in 2014. While the city's ranking was quite low when compared with other states, it topped among other Union Territories in registering corruption complaints. According to the NCRB data, 64 cases were registered during the year--highest among Union Territories. The city is ranked 15th among other states and Union Territories in registering cases under the Prevention of Corruption Act and IPC against police personnel.

While 4,246 cases were registered across the country in 2013, a total of 4,966 cases were registered in 2014. Maximum cases were registered under sections 7 (Public servant tak ing gratification other than legal remuneration in respect of an official act) and 13 (criminal misconduct by a public servant) of Prevention of Corruption Act. Investigation was pending in 163 cases from the previous year. In 2014, only 22 cases were investigated.

Only two cases were transferred to local police last year.There were just six cases in which chargesheets were not laid but final reports were submitted. A total of 207 cases are pending for probe, while in 63.6% of cases chargesheet has been registered.

In 2014, complaints against police in cases other than corruption decreased. While in 2013, 12,427 complaints were registered, it decreased to 11,902 in 2014. Department inquiry was initiated in only 540 cases, while no case was sent for regular department action.

2015: 52% decline in graft complaints

The Times of India, Aug 05 2016

Graft plaints saw 50% dip in '15, lowest in 4 yrs: CVC

There has been a decline of 52% in graft complaints with less than 30,000 of them received last year as against over 62,362 in 2014, the central vigilance commission (CVC) has said.

The CVC received 29,838 complaints in 2015, the lowest in the past four years, according to a report tabled in Parliament. The probity watchdog had received 31,432 and 37,039 complaints of alleged corruption during 2013 and 2012 respectively , says the commission's annual report for 2015. In 2011, it had got 16,929 such complaints.

“The decline is attributed to the multiple complaints received from some complainants during 2014,“ the report said. Of the total complaints received last year, 12,650 were vague or unverifiable. “ The CVC calls for inquiry reports from the appropriate agencies only in those complaints which contain serious and verifiable allegations and there is a clear vigilance angle. The inquiry reports are to be sent to the commission within three months,“ it said.

However, it is observed that in a majority of cases there is considerable delay in finalising and submission of reports to the commission, the CVC said. “ In such situation, the commission may call Chief Vigilance Of ficers (CVOs) concerned personally with records and documents,“ it said.

A total of 30,789 complaints (including some from those made in 2014) were disposed last year. Similarly, a total of 62,099 and 33,284 complaints were disposed during 2014 and 2013. “Out of complaints disposed of during the year, only 179 (0.58%) were found serious enough to warrant further action,“ it said.

Meanwhile, CVC also said that special CBI courts designated for corruption cases are being allotted matters of other agencies, as it expressed concern over delay in disposal of cases, some pending for over 20 years.“On an average it takes more than five years for judicial proceedings in any case under the Prevention of Corruption Act to conclude .“

2015: Railways, banks, finance, telecom, UD

The Times of India, Aug 04 2016

Railways has topped a list of government organisations against which complaints of alleged corruption -over 12,000 -were received by the Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) in 2014-15.

As many as 12,394 complaints of alleged corruption were received against railway employees followed by 5,363 against bank officials and 5,139 against government of Delhi, the CVC said in its annual report for 2015 which was tabled in Parliament.

A total of 4,986 such complaints were received against officials working under finance ministry , 3,379 against those in telecom ministry and 3,079 against employees working under urban development ministry , it said. These were among the to tal of 56,104 complaints of alleged corruption received by chief vigilance officers (CVOs), who act as a distant arm of the CVC, of various government departments. Of the total complaints, 38,192 were disposed of and 17,912 were pending, the report said.

As many as 2,741 compla ints were against employees working in petroleum mini stry , 2,235 against tho se in food and consu mer affairs, 2,084 un der Central Board of Direct Taxes, 1,601in steel ministry and 1,460 under Central Board of Excise and Customs, the report said. There were 1,377 complaints of alleged corruption against employees working under human resource development ministry , 1,143 against those in health ministry and 1,018 in information and broadcasting ministry , it said.

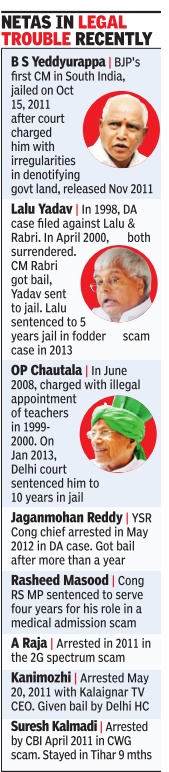

Chief Ministers

Jaya first CM in office to be convicted

The Times of India TIMES NEWS NETWORK Sep 28 2014

Several Indian politicians, including former and serving CMs, have been imprisoned for political reasons and a handful have been jailed on corruption charges. But J Jayalalithaa is the first CM in office to go to jail on the charges of amassing illegal wealth.

Former CMs jailed for corruption are Lalu Prasad, Madhu Koda, B S Yeddyurappa, O P Chautala and Jagannath Mishra.

Lalu Prasad was the first former CM to be imprisoned in a corruption case. He was first jailed in July 1997 in one of the fodder scam cases. He was finally convicted in September last year. Three-time CM of Bihar Jagannath Mishra was first jailed in 1997.He too was convicted in September 2013.

Jharkhand ex-CM Madhu Koda, was sent to jail in November 2009, facing charges of having accepted bribes for allotting mining contracts in the state. Karnataka ex-CM B S Yeddyurappa was charged with favouring his sons in land allotments.

Om Prakash Chautala, the former CM of Haryana, was charged with taking bribes for recruiting 3,000 teachers and sentenced to 10 years in jail.

CISF’s cash limit upheld

HC okays CISF rule that staff on duty can have only Rs 20

Rosy Sequeira

Mumbai:

The Times of India Nov 05 2014

The Bombay high court has upheld a 2007 circular of the Central Industrial Security Force allowing its personnel to keep only up to Rs 20 with them while on duty .

A division bench of Justices N H Patil and R V Ghuge agreed that the measure was a step towards curbing illegal gratification and possible security breach at various sensitive locations. The court said the office ordercircular of August 23, 2007, cannot be a substitute to a rule or service condition but “keeping in view the object and purpose for which the CISF has been brought into existence, we are of the opinion that the office order needs to be given due importance“.

The ruling came on a plea by constable Ram Tiwari, who was found on August 3, 2008, with Rs 500 while on duty at JNPT, Navi Mumbai. On April 10, 2009, constable Ram Tiwari was held guilty of illegal gratification and removed from service. On September 8, 2009, “keeping in mind his unblemished service record of 16 years“, CISF authorities replaced the punishment with “compulsory retirement“ with full pension. The chargesheet said an inspector saw Tiwari counting money and directed a sub-inspector to frisk him. While removing Tiwari's belt, notes worth Rs 500 fell near his leg. Tiwari denied the money belonged to him and claimed the inspector implicated him due to an animosity .

CISF advocate Vinod Joshi argued that the Rs 500 found on Tiwari could only have come by way of bribes as he had declared before duty he had only Rs 20. The possibility of CISF personnel indulging in illegal gratification from container drivers cannot be ruled out and to curb such acts the circular allowed “CISF personnel on duty to keep only Rs 20 on their person as pocket money“. Joshi said if the punishment is set aside, it will send a wrong signal and “seriously affect the discipline maintained in the CISF“.

Court judgements

Don't pay taxes if no end to graft: HC

The Times of India Feb 03 2016

Vaibhav Ganjapure

`Let Govt, Babus Understand The Citizens' Excruciating Pain And Anguish'

Expressing serious concern over the ever-gro wing number of corruption cases, the Nagpur bench of Bombay high court on Tues day called on citizens to raise voice against “this menace“ and also asked them to “refu se to pay taxes by launching a non-cooperation movement“ if the government fails to control it.

Terming corruption as a “hydra-headed monster“, Jus tice Arun Chaudhari said it is high time citizens came toget her to tell their governments that they have had enough “The miasma of corruption can be beaten if all work toget her. If it continues, taxpayers should refuse to pay taxes through a non-cooperation movement,“ said Chaudhari.

Justice Chaudhari made these observations while pas sing several strictures on the Maharashtra government and Bank of Maharashtra (BOM) for overlooking embezzlement of funds worth Rs 385 crore in Lokshahir Annab hau Sathe Vikas Mahamandal (LASVM), an organisation which was set up for the uplift of Mathang community . He asked director general of police (DGP) to find out veracity of such cases reported in newspapers and act immediately .

While passing strictures, the judge rejected the anticipatory bail application of Pralhad Pawar, LASVM's district manager in Bhandara.He was accused of embezzling Rs 24-crore funds meant for distribution to poor members of the Mathang community , who come under the scheduled caste category. “The taxpayers are in deep anguish. Let the government as well as mandarins in corridors of power understand their ex cruciating pain and anguish.They have been suffering for over two decades in the state.There is an onerous responsibility on those who govern to prove to taxpayers that eradication of corruption would not turn out to be a forlorn hope for them,“ said Chaudhari.

Observing that corruption in government-run financial organisations had become the order of the day in the last two decades, the judge said, “Ethics and morals have taken a back seat in modern India's scheme of things.“Taking a dig at employees' unions, Chaudhari flayed them for supporting such corrupt workers.

Culpability of family

The Times of India, Jun 05 2016

Siddharth Shankar Pandey

Corrupt official's kin equally guilty: Court

Family members of a corrupt official are equally responsible if they share his ill-gotten wealth, a CBI court in Jabalpur ruled on Friday while sentencing a central government official along with his wife, son and daughter-in-law to five years of rigorous imprisonment. The five-year-old grandson of the official, who was left alone in the house after the entire family was sentenced, has been shifted to jail on the family's request, the prosecution said.

While holding the official guilty of misappropriating funds to the tune of Rs 94 lakh, CBI judge Yogesh Chandra Gupta also slapped a fine of Rs 2.5 lakh each on the four. CBI special public prosecutor Pratish Jain told the court that Surya Kant Gaur, 61, a resident of Jabalpur who was posted as deputy accountant in the defence accounts department, had transferred funds to the accounts of his three relatives. CBI raided Gaur's prem ises on July 14, 2010, and found records of transactions to the tune of Rs 94 lakh, most of which were disproportionate to his income. The court sentenced the accused after scanning the evidence, Jain told.

Reacting to the verdict, senior government advocate Satish Dinkar said, “There are certain provisions for punishment under Prevention of Corruption Act for such cases if illegal transaction is proved. In all cases of disproportionate assets, kin can also be made accused.“

Disproportionate assets

By themselves, not a crime: SC

The Times of India, Jun 02 2016

By itself, disproportionate assets not crime: SC

Mere possession of assets disproportionate to known sources of income is not an offence and a person can be held guilty only if it is proved that the assets were acquired through illegal means, the Supreme Court said. “Disproportionate assets per se is not a crime. If it is proved that some of the income is not proven, then only the offence is complete, otherwise, it will be an inference only” , a bench of Justices P C Ghose and Amitava Roy said while hearing an appeal against the acquittal of Tamil Nadu CM J Jayalalithaa in a Rs 67 crore disproportionate assets case. The Karnataka government, which challenged the acquittal, told the bench that the high court verdict was “perverse“ as it “committed error“ in calculating the CM's assets. It said the assets, expenditure and income of the accused was considered jointly and they couldn't make out a case for sepa rate assessment now. The bench said, “Suppose you prove all the accused are together and it is the same money of accused No. 1 (Jayalalithaa) which was being circulated, does it lead to conviction? Will it mean the money ... was from income obtained from unknown sources?“ Appearing for the Karnataka government, senior advocates Dushyant Dave and B V Acharya claimed the HC had committed a grave error in calculating the disproportionate assets to the extent of 8.12% only when it actually worked out to 76.7% of the total income of the AIADMK chief and others.

Besides Karnataka, DMK leader K Anbazhagan and BJP leader Subramanian Swamy also challenged the acquittal of the AIADMK chief, her close aide Sasikala and two relatives, V N Sudhakaran and Illavarasi. The petitioners contended that the HC had undervalued properties owned by Jayalalithaa and committed a mathematical error while calculating her income from her various ventures, including agricultural income and the loan taken by her from nationalised banks.

The Karnataka government said if the error committed by the HC was rectified, the percentage of her disproportionate assets would be around 34.50% which was erroneously fixed at 8.12% by the court.The HC had held that Jayalalithaa's disproportionate assets amounted to Rs 2.82 crore against the prosecution's claim of Rs 66.5 crore and acquitted her on the ground that it was less than 10% of her income.

“It is respectfully submitted that the conclusions reached by the judge are not based on proper appreciation of evidence and the conclusions reached are bordering on perversity and is, therefore, liable to be set aside. The judgment lacks reasoning, is not logical and is cryptic. The evidence has not been considered objectivelyand lacks deliberation,“ the Karnataka government said in its petition.

A Bengaluru court had convicted Jayalalithaa for amassing wealth disproportionate to her known sources of income during her first term as CM in 1991-96 .

The court sentenced her to four years imprisonment and directed her to pay a fine of Rs 100 crore. Sasikala, her disowned foster son Sudhakaran and Illavarasi were also convicted. Their conviction was set aside by the high court.

Effects of corruption

Lower corruption boosts GDP growth: SBI report

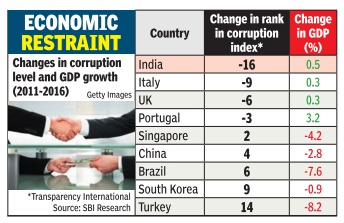

Lower corruption level boosts GDP growth, says SBI report, Oct 11 2017: The Times of India

Does reduction in corruption lead to economic prosperity? Data from around the world, including India, show that a lesser level of corruption is directly proportional to higher GDP growth. According to an SBI report, between 2011 and 2016, as India improved its rank in Transparency International's global corruption index from 96 to 79, its GDP growth rate improved by half a percentage point. A similar trend was observed for countries like the UK, Portugal and Italy. During the period, these countries succeeded is bringing down corruption and their economic growth rate improved.

In contrast, the data shows that in countries like Turkey , South Korea China, Brazil and Singapore, there was an increase in the level of corruption, which was accompanied by drop in GDP growth rates. Of these countries, corruption in Turkey increased by 14 points, and its GDP growth rate fell by 8.2 percentage points.

“In essence, corruption at public places is often considered a strong constraint on growth and development.It not only increases transactional costs, inefficient investments and mis-allocation of resources but also distorts decision making and results in misplaced priorities,“ the report said. Weeding out corruption was one of the main election promises of the Modi-led government.

Apparently, the improvement in corruption level in India has translated into foreign fund inflows. The data shows that there has been an significant improvement in foreign investor confidence towards India. Net FDI inflows to India has increased by 64% in last six years -from $21.9 billion in fiscal 2012 to $35.9 billion in fiscal 2017, it pointed out.

2015

2015: An increase by 5%

The Times of India, Sep 01 2016

Corruption cases up by 5% in 2015: NCRB

Neeraj Chauhan

Corruption remains a scourge in the country with the number of cases reported showing a rise of 5% in 2015 over the preceding year, data released by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) showed. According to the NCRB, 5,867 corruption cases were reported in 2015, up from 5,577 in 2014. The only silver lining was that the annual growth rate of such cases came down -from 13.93% in 2014 to 5.1% in 2015. in 2013, 4,895 cases of corruption were registered.

By the end of 2015, 13,585 cases of corruption were under investigation, mostly related to public servant taking bribery and criminal misconduct.

The NDA, coming to power on an anti-corruption plank, has introduced several steps to curb graft in government organisations, public sector units, banks and other departments including increased oversight by the Central Vigilance Commission, streamlining government machinery by fixing accountability on officials, digitisation of government projects and policyoriented decision making.

The government amended the Prevention of Corruption Act last year to classify corruption as a heinous crime and longer prison terms for both bribe-giver and bribe-taker. The amendments also sought to ensure speedy trial, limited to two years, in corruption cases.

However, the problem is far from solved. The highest number of corruption cases were registered in Maharashtra (1,279), Madhya Pradesh (634), Odisha (456), Rajasthan (401) and Gujarat (305). Uttar Pradesh reported only 60 cases of corruption and West Bengal reported 18. Delhi reported a 50% decline in corruption cases with 31 cases in 2015, compared to 64 in 2014.

The report said 29,206 corruption cases were pending trial in courts while accused persons were acquitted or discharged in 1,549 cases in 2015.

Former CBI director Joginder Singh said there was no seriousness on curbing corruption. “If any government (state or Centre) wants to be serious about corruption, there should not be the option of taking sanction for a government official. If a person has been caught red-handed taking bribe, why is there the need for taking prosecution sanction for him. There is also need to make Prevention of Corruption Act stricter,“ he said.

2015: Survey by National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER)

The Times of India May 24 2015

Dipak Dash

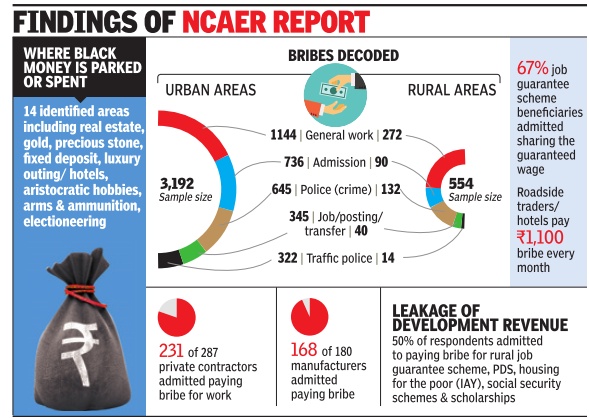

Govt survey pegs bribe at Rs 4,400yr per family

An average urban household in India pays around Rs 4,400 annually as bribe while rural households shell out Rs 2,900, a government-commissioned study on unaccounted wealth has revealed. Individuals in Lucknow, Patna, Bhubaneswar, Chennai, Hyderabad, Pune and rural areas paid maximum amount of bribe for general work, admission and to police personnel, the survey by National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) showed.

In the cities, an average Rs 18,000 was paid for securing jobs and transfers, while bribes to traffic police personnel totalled Rs 600 a year. The survey was conducted between September and December 2012. Surveys showed that black money is generated through bribes and pay-offs to bureaucrats and politicians, which could range from award of contracts to leakages from development schemes, mining, sale of oil products and settlement of non-performing loans by banks.

The National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER), along with the National Institute of Public Finance & Policy and National Institute of Financial Management, had been tasked by the Centre to provide black money estimates, following an observation by the parliamentary standing committee on finance. While the reports were submitted to the finance ministry in 2013 and 2014, it is only now that they have been circulated for comments from other departments.

Pointing out that bribe is rampant in rural areas, the NCAER survey report has revealed how half the beneficiaries of government schemes, including MNREGS, public distribution system, Indira Aawas Yojna, social security programmes and scholarships had to offer money to get their entitlement. This finding is based on a survey of 359 households in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra. Despite government claims, the report estimates that leakages are more common under MNREGS.

It also highlights the extent of corruption, which ultimately generates black money , so far as public sector investment is concerned. Based on interviews of retired government officials, the report suggested that public sector investment is an easy source of illegal funds for politicians and bureaucrats. The unaccounted money earned could be 2-10% of the project cost and it could cross 20% due to delays. The report estimated that 5-10% of the additional cost in siphoned off.

Based on a survey of private contractors in 15 states, including Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Delhi, Gujarat, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal, the report says on an average 9% of the project cost is paid as bribe. About 80% of contractors interviewed have admitted of paying bribe for works. It is no different so far as manufacturing sector is concerned. According to the report, 91% of the respondents admitted to have paid bribe.

The report has also brought to light how on an average people running roadside vends and eateries pay approximately Rs 1,100 per month. These findings are based on a survey in Delhi, Noida, Lucknow, Patna and Hyderabad. The report says about 13% of the earnings are given as bribe.

2015: Defence procurement corruption in South Asia

The Times of India, Nov 04 2015

Kounteya Sinha

Corruption high in India's defence deals: TI

Defence procurement corruption in India has been accessed to be “high“, with a large mass of its procurements shrouded in secrecy with low levels of accountability.

Corruption in defence procurement in three of its neighbours China, Sri Lanka and Pakistan has been found to be “very high“. The Global Defence Anti-Corruption Index to be announced by Transparency International on Wednesday revealed that the Chinese military spending has increased by 441% in 2005-15, India by 147%, South Korea by 106%, Pakistan by 107%, Bangladesh by 202%, and Sri Lanka by 197%.Within ASEAN, there have been huge increases as well: Indonesia by 189%, Thailand by 207%, Cambodia by 311%, and the Philippines by 165%. Accessing the Indian experience, the Index said the Indian army was found to be illegally running golf courses on government-owned land while the air force officials used defence land for unauthorised use, such as building of shopping malls and cinema halls. It also says that India's defence institutions have been found to be involved in exploitation of natural resources.

Citing an example, the report says awards for contracts by Riflex, the paramilitary force in north-east India, were essentially bought through personnel for kickbacks amounting to 35% of the tender cost.

“India has no designated body tasked with responsibility over ethics or anti-corruption within the ministry of defence. There is no Inspector General position.The Public Accounts Committee, the CAG have held the MoD to account for the illegal use of land for private golf clubs,“ the report says.

According to the report “as the second largest military spender in the region, India distinguishes itself through independent institutions with clear mandates for overseeing defence agencies.The CAG along with the Pub ic Accounts Committee have exercised active oversight“.

The report also has praise or India. It says, “The use of ntegrity pacts have been a powerful binding instrument, involving independent monitoring by the Central Vigilance Commission.“

2016

CPI: India moves up from no.85 to 76

The Times of India, January 27, 2016

Please find below the score of the South Asian countries in the Corruption Performance Index, 2015

Source: www.transparency.org/cpi2015

| Country | Rank: 2015 | Score: 2015 | Score: 2014 | Score: 2013 | Score: 2012 |

| Afghanistan | 166 | 11 | 12 | 8 | 8 |

| Bangladesh | 139 | 25 | 25 | 27 | 26 |

| Bhutan | 27 | 65 | 65 | 63 | 63 |

| India | 76 | 38 | 38 | 36 | 36 |

| Nepal | 130 | 27 | 29 | 31 | 27 |

| Pakistan | 117 | 30 | 29 | 28 | 27 |

| Sri Lanka | 83 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 40 |

India's score in the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for 2015 remained unchanged at 38 as it was in the previous year. As per the scoring system adopted, higher the score points on a scale of 0-100, lower is the corruption in that country. Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) 2015 shows that India has moved up in rank from 85 position to 76 (however the number of countries ranked in 2015 was 168 against 174 nations in 2014). Based on expert opinion from around the world, CPI measures the perceived levels of public sector corruption worldwide. Barring Bhutan ranked 27, which with a score of 65 fares much better than India, other neighbouring countries continue to have a poor record. While China at rank 83 and Bangladesh at rank 139 have reported no improvement, scores of Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Nepal have increased marginally over 2015.

Referring to the high perception of corruption across the Asia Pacific region, the CPI report says that in India and Sri Lanka leaders are falling short of their bold promises whereas governments in Bangladesh and Cambodia are exacerbating corruption by clamping down on civil society. It adds that in Afghanistan and Pakistan a failure to tackle corruption is feeding ongoing vicious conflicts, while China's prosecutorial approach isn't bringing sustainable remedy to the menace.

The Global Fraud Report 2015-16

The Hindu, June 27, 2016

SHARAD RAGHAVAN

92% of firms surveyed have seen rise in exposure to fraud

India among top 3 regions in corruption-linked fraud

An overwhelming 80 per cent of companies polled in India said they had been victims of fraud in 2015-16, up from 69 per cent in 2013-14, according to a survey report.

The Global Fraud Report 2015-16 by risk mitigation consultancy Kroll, with the aid of the Economist Intelligence Unit, found that the perceived prevalence of fraud in India is the third-highest among all countries and regions surveyed across six continents. Only Colombia (83 per cent) and Sub-Saharan Africa (84 per cent) surpass India.

The report's authors observed that while the incidence of fraud was on the rise globally, a combination of a lack of preventive measures at Indian companies and a poor legal system had resulted in 92 per cent of the respondents saying they had witnessed an increase in exposure to fraud.

The India-centric data in the report shows that the highest incidence of fraud as reported by Indian companies is due to what the report terms ‘corruption and bribery’.

Dubious record in graft-linked fraud

A quarter of the respondents said they registered losses due to this. On average, the worldwide survey found that only 11 per cent of the companies reported corruption and bribery as a source of revenue loss.

Procurement fraud

The second-highest fraud-related source of loss of revenue in India is vendor, supplier or procurement fraud, which affected 23 per cent of the companies, which is also higher than the global average of 17 per cent.

Interestingly, the 2013-14 survey found that the highest source of fraud-related revenue loss for Indian companies came from theft of physical assets or stock (33 per cent) and both information theft, loss or attack and corruption and bribery were on a par (24 per cent).

High turnover

The latest report also finds that the biggest factors exposing Indian companies to fraud have changed over the last few years. Where the previous report pegged IT complexity as the biggest contributor to fraud, the 2015-16 report says the new drivers of fraud are high employee turnover and cost restraints over pay.

“While companies in India are willing to spend to improve their level of anti-fraud protection, it appears that such funds are not being invested appropriately,” the report's authors said. “For respondents that had identified the perpetrator, 59 per cent indicated that junior employees were leading players in at least one such crime.”

“Despite these vulnerabilities and the high proportion of fraud perpetrated by insiders, only 28 per cent of companies in India invest in staff background screening and only 55 per cent invest in vendor due diligence,” they added.

Legal hurdles

Compounding the problem of inadequate preventive measures is the issue of what happens once fraud has been detected. Often, the legal system in India is not quick enough to make it worth the company’s while to go to court, the report's authors said.

“First, the bar is set high for what constitutes evidence of fraud in a court of law in India; second, once in court, it can take years to settle disputes, by which time the value of the investment may have significantly eroded,” said Reshmi Khurana, MD and head of Kroll’s India office. “These factors explain why PE (private equity) investors are usually not keen to go to court immediately following a dispute.”

2017

See graphic

2017, Transparency Perception Index

See graphic

India gets just 40100 for transparency, Jan 26, 2017: The Times of India

India has nothing much to cheer about, when it comes to its rating in Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index (CPI), 2016, released at Berlin.

The country's rank has moved down from 76 to 79. However, as the organisation points out, this is not the best judging matrix as 176 countries were assessed in the 2016 survey , as against 168 in the previous year's index and ranks can change depending on the number of countries covered. It is the points scored which matter more. Here, with a score of 40, a slight improvement over 38 scored in last year's index, India's performance is not promising.

If it is any consolation, India shares this rank and score with its BRICS counterparts, Brazil and China.

Russia, at rank 131 and a score of 29 , trails behind keeping company with India's neighbour Nepal. Among the Asia-Pacific countries, Singapore leads by standing at seventh position globally .

In a communique to TOI, Transparency International's South Asia expert says: “Despite strong rhetoric by politicians on tackling corruption, India continues to stagnate in CPI with a poor score of 40 out of 100. Key legislations enabling anti-corruption infrastructure such as the Lokpal Act too often remain on the backburner of the government's agenda when it comes to implementation. In cases where anticorruption activists have achieved strong momentum, such as enacting the Whistleblowers Act, we see the government backtracking on its pledges for transparency using exemptions for other anti-corruption laws such as the Right to Information Law. In 2016, we saw the Lokpal Act being watered down through removing enabling provisions for asset declaration, a key preventative measure for any country .“

“It is too early to tell if demonetisation will bring about a dramatic reduction in corruption as envisaged.However, widespread public support for such aggressive anti-corruption measures show that the Indian public is eager to tackle the scourge of corruption,“ he adds.

CPI-2016 indicates that none of the 176 countries assessed get a perfect score, with 69% (120 countries) scoring below 50 points, on a scale from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). This year, more countries declined in the index than improved, showing the need for urgent action, says the anti-corruption global organisation. CPI ranks countries based on how corrupt its public sector is perceived to be.

India: highest bribery among 16 Asia countries

Lubna Kably, `India tops Asia Pacific nations in bribery rate', March 8, 2017: The Times of India

India had the highest bribery rate among the 16 Asia Pacific countries surveyed by Transparency International (TI). Nearly seven in 10 Indians, who had accessed public services, had paid a bribe, a bulk of them for access to government healthcare and for procuring documents.Contrast this with the least corrupt country: Japan, where only 0.2% of the respondents reported paying a bribe.

The only silver lining is that over a half of the respondents from India were positive about the government's efforts to combat bribery . About 63% of respondents in India also felt that they , as individuals, had the power to fight corruption.

The Global Corruption Barometer for the Asia Pacific Region was released by Transparency International (TI), an anti-corruption global civil society organisation, on March 7 in Berlin. Approximately 90 crore people, or just over one in four, across 16 countries in Asia Pacific, including some of its biggest economies like India and China, are estimated to have paid a bribe to access public services. TI spoke to nearly 22,000 people in these countries about their recent experiences with corruption.

Across the Asia Pacific re gion, just 22% of the respondents thought that corruption had decreased over the past twelve months while 40% of the respondents (41% in India) were of the option that it was on the rise. In mainland China 73% of the respondents felt that the level of corruption had worsened. This was the highest of any country surveyed.

For the purpose of this survey, TI concentrated on bribes paid for procuring six key public services viz: public schools, public hospitals, official documents (such as identification card, voters card), public utility services, the police and courts. In India, payment of bribery dominated for services relating to access to government healthcare and procurement of documents. The right to public services is severely undermined by the high bribe ry rates, as reflected in the survey .

Bribery often hurts the poorest and the vulnerable the most. In Asia Pacific, 38% of the poorest people have paid a bribe, which is the highest of any income group. Nearly 73% of those who paid a bribe in India were from the poorer sections of society; in Pakistan and Thailand, this percentage was 64% and 46% respectively. Surprisingly , a reverse trend was found in some countries such as China, where the richer sections (31%) were more likely to pay a bribe.

Ilham Mohamed, regional coordinator, South Asia & Mongolia at TI told TOI: “ At the state level, anti-corruption policies must be focused on catering to the poor, best practices agreed for Lokayuktas and overlaps with other enforcement agencies resolved.“

2017: Karnataka most corrupt state?

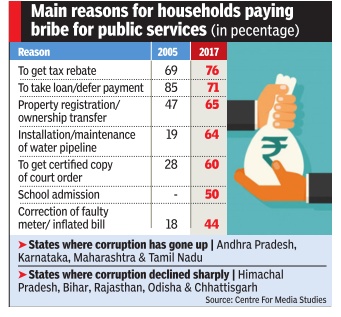

Dipak Dash, Survey: Karnataka most corrupt state, April 28, 2017: The Times of India

See graphic: Main reasons for households paying bribe for public services, 2005, 2017

Karnataka occupies the first slot in a list of states perceived to be corrupt on the basis of people's experience in paying bribes for public services, a survey conducted by an NGO has revea ed. Karnataka is followed by Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Jammu & Kashmir and Punjab.

The Centre for Media Stu dies survey , which covered 20 states, found Himachal Pradesh, Kerala and Chhattisgarh to be the least corrupt.The report said around onethird of the households experienced corruption in public services at least once during the last one year in compari son to about 53% of households that admitted to paying bribes during a similar study in 2005. The survey covered 3,000 odd persons, both in urban and rural areas.

It also claimed that more than half of the respondents felt that the level of corruption had decreased in public services during the demonetisation phase of November and December 2016.

The report estimated that the total bribe paid by households across 20 states and 10 public services was Rs 6,350 crore in 2017 as against Rs 20,500 crore in 2005.

However, the study indicated how a lot still remained to be done to reduce corruption in public services.