Colour films in Hindi-Urdu

(→Is there a relationship colour and box office success?) |

|||

| Line 325: | Line 325: | ||

1970 No B&W film made it to the Top 20. | 1970 No B&W film made it to the Top 20. | ||

| − | ==== | + | ====Was there a relationship colour and box office success?==== |

The relationship between a film being in colour and its success at the box office, it will be seen, is very strong, but not one hundred per cent. Well-made B&W films have, in a few cases, done better than colour films that were not equally good. And yet such films have been few and far between. | The relationship between a film being in colour and its success at the box office, it will be seen, is very strong, but not one hundred per cent. Well-made B&W films have, in a few cases, done better than colour films that were not equally good. And yet such films have been few and far between. | ||

| Line 335: | Line 335: | ||

Shikari was a ‘B film’ or even a ‘C film’ but it did better than a major ‘A film’ like Mujhe Jeene Do mainly because it was in colour. Similarly, Parasmani, also a B or C film, entered the Top 20 partly because of hit music (it was music director-duo Laxmikant-Pyarelal’s debut film) and partly because of its few colour scenes. | Shikari was a ‘B film’ or even a ‘C film’ but it did better than a major ‘A film’ like Mujhe Jeene Do mainly because it was in colour. Similarly, Parasmani, also a B or C film, entered the Top 20 partly because of hit music (it was music director-duo Laxmikant-Pyarelal’s debut film) and partly because of its few colour scenes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Cinema-TV-Pop|CCOLOUR FILMS IN HINDI-URDUCOLOUR FILMS IN HINDI-URDUCOLOUR FILMS IN HINDI-URDU | ||

| + | COLOUR FILMS IN HINDI-URDU]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|CCOLOUR FILMS IN HINDI-URDUCOLOUR FILMS IN HINDI-URDUCOLOUR FILMS IN HINDI-URDU | ||

| + | COLOUR FILMS IN HINDI-URDU]] | ||

=Internet bloopers about Hindi-Urdu cinema= | =Internet bloopers about Hindi-Urdu cinema= | ||

Revision as of 10:04, 13 November 2022

Readers can send additional information, corrections, photographs and even on their online archival encyclopædia only after its formal launch. |

Colour films in South Asia: 3--(Hindi-Urdu films)

By Parvez Dewan

(With additional inputs by the film historians Mr Sudhir and Mr Sajeeth Naveen Lourdes.)

The above frame proves beyond doubt that Jhansi ki Rani was only in ‘Color by Technicolor,’ which is not the same as full-fledged Technicolor (See note in the body of the article).

When was Jhansi Ki Rani released? International sites like Imdb and YouTube say: 1956. Reliable Indian sites say: 1952. Mr Sudhir adds, '1956 it seems is the year, when a highly-edited English version was released in USA' The censor certificate on YouTube is smudged and the date that can be discerned vaguely could be 1952, 1953 or 1958.

See also Binaca Geet Mala 1957: greatest hits for a richer Technicolor still.

The film’s makers brought in the services of celebrity photographer Fali Mistry for the Technicolor sequences, and S. Hardip for the Gevacolor photography. A third photographer shot the main, B&W body of the film.

See also Binaca Geet Mala 1957: greatest hits

See also Binaca Geet Mala 1957: greatest hits

(Part 3 of 'Colour films in South Asia')

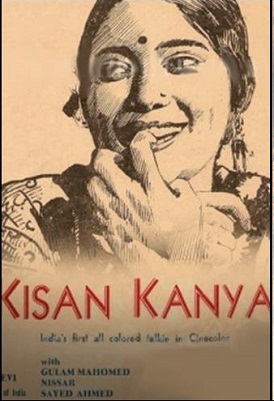

Kisan Kanya, India’s first colour film

Attempts to shoot the first Indian colour film failed when the negative for Sairhandri, directed by Rajaram Vankudre Shantaram, was ruined during processing in Germany. Prabhat Film Company's “Sairandhri” was the first talkie film produced in Multicolour in 1933. However, its colour quality was not satisfactory and what could be seen was black and white.

Kisan Kanya (lit: the peasant girl; 1937/ Dir: Moti B. Gidvani; prod. Ardeshir Irani; screenplay and dialogues: Saadat Hasan Manto) was arguably India’s first colour film to be actually released. It used the Cinecolor process. This story about rural poverty and crime did not go down well with mass audiences, so colour films did not catch the public imagination—till Aan (1953).

India was thus the sixth country to have produced a colour film; at most seventh, if firmer dates about the first Soviet colour film indicate otherwise.

Two sources(asia.isp and RaqsMediaCollective)say that Bhavnani Productions ‘Rangeen Zamana” produced and directed by M. Bhavnani in 1948 (released as “Ajit” in 1949) was the first feature film produced in Kodachrome and blown up to 35mm. It has not been possible to get independent corroboration of this claim, but if true this is very impressive because Kodachrome was a superior (and expensive) technology, as good as the best in the world.

Technicolor

Technicolor in India

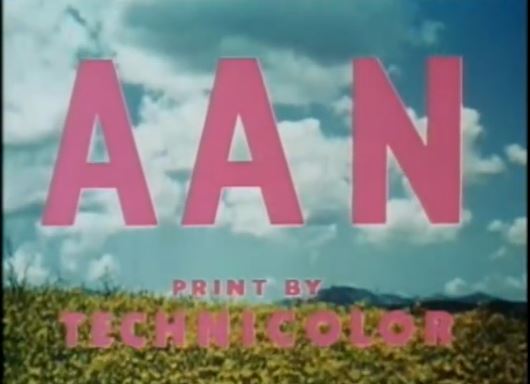

Aan, a Dilip Kumar- Nimmi starrer by Mehboob Khan, was the first Indian film with prints in Technicolor, the most expensive colour format of that era, or ever. It was shot in 16 mm and later blown up to 35 mm. It was a landmark success. Sudhir adds, ‘It was shot on 16 mm KodaChrome Reversal negative and then blown-up and printed by Techicolor Labs, London on 35 mm release print. As a safety measure, it was also shot on regular b&w negative. Mr. Faredoon A. Irani, the cinematographer spent few months in Hollywood, to learn some fine points on colour photography.’ (When was Aan released? The Shemaroo print does not have a censor certificate. Wikipedia and Sudhir say: 1952; IbosNetwork.com and several websites say 1951. The Moser Baer print was recertified in 1977, probably after 25 years. Hence 1952 seems to have been the year.)

V. Shantaram’s Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje (1955: shot in Geva Color), Mehboob Khan’s Mother India (1957) and V. Shantaram’s Navrang (1959), all released in 'Color by Technicolor,' too, were the biggest—or among the biggest—hits of their respective years. Only Sohrab Modi’s lavishly produced 'Color by Technicolor' Jhansi Ki Rani (1956) fared badly at the box office.

India's first film shot on Technicolor negative (even if partly): The film "Aasha" (1957) starring Kishore Kumar and Vyjanthimala had sequences in B&W, Gevacolor and Technicolor. The title of the film, songs like Haal Tujhe Apni, Chal Chal Re, Zara Ruk Ruk were shot in Gevacolor. Songs like Eena Meena Deeka (both versions) and the climax scene were shot in Technicolor while the rest of the film was in B&W. The film’s makers brought in the services of celebrated photographer Fali Mistry for the Technicolor sequences, and S. Hardip for the Gevacolor photography. A third photographer shot the main, B&W body of the film.

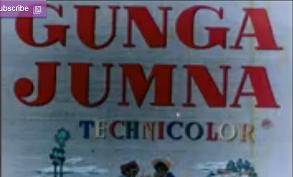

Technicolor’s run of success continued into the 1960s, but not as triumphantly. Gunga Jumna, and Sangam were, again, the biggest hits of their respective years. But Mehboob Khan's 'Son of India' (also 'Color by Technicolor'; Sudhir feels that it most probably was shot in EastmanColor 1962) and Mera Naam Joker tanked. Around the World (1967/ India's first in 70mm) was an average performer, which was bad considering its budget. (Gunga Jumna, Sangam, Around the World and Mera Naam Joker were in Technicolor proper, as opposed to 'Color by Technicolor.' That means that Gunga Jumna was the first Technicolor film in Hindi-Urdu (and perhaps India). This writer has checked the credit titles of every one of the supposedly Technicolor films mentioned on this page before making this assertion. Veerapandiya Kattabomman (1959) does not claim to be in Technicolor in its English title. The quality of its colours is very uneven--ranging from the weak in the beginning to superb later on.)

So, Technicolor was no longer a guarantor of success. Besides, Eastmancolor, which had pleasant colours, though not the well-defined details or dignified hues of Technicolor, had reached India, and was much cheaper than Technicolor.

Gunga Jumna was processed by both Technicolor, London, UK and Ramnord Research Lab, India.

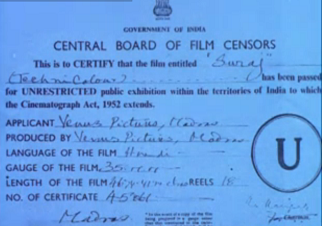

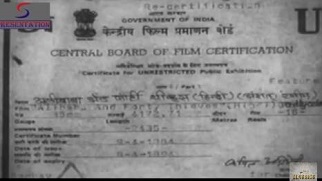

The censor certificate of Suraj said that the film was in Technicolor; its own credits informed us ‘Negative processed by Gemini…Madras.’ Saathi too had been processed by Gemini of Madras. There is nothing in the film’s credits to indicate the colour film used, though Saathi was supposed to have been in Technicolor and the richness of its colours indicate as much. Mera Naam Joker was processed at Ramnord Research Lab, India.

Both Mere Mehboob and Palki were in Eastmancolor, though the general impression is that they were in Technicolor.

The Technicolor process

Technicolor was expensive because the image being photographed (i.e. the light coming from this image) had to pass through three strips of black-and-white film. Together these three strips formed a rich colour image. This colour went by the brand name Technicolor.

The camera’s lens split the light coming from the actors and the background into two beams, one of which went through a green filter and the other through a magenta filter. The topmost strip could receive only blue light and recorded blue images. The green filter obstructed red and blue light; the second strip received this image. The magenta filter kept green light out; the third strip recorded the residual colours.

The cyan, magenta and yellow dye images from these three negatives were superimposed on a single strip of film, which resulted in sharp, nuanced Technicolor images.

The historical benefit of this complicated and expensive technology is that old Technicolor prints (notably, Mughal-e-Azam ) retain their original colours, while pictures shot on cheaper colour films have faded or lost one shade or even one or more colours. The original colours of Mughal-e-Azam’s two Technicolor sequences remain vastly crisper, more detailed and lustrous than the bulk of the film, which was colourised from black and white in 2004.

'Color by Technicolor'

Those who appreciate good colour photography often wonder why of all Technicolor films ‘Mother India’ has the narrowest range of colours, the images do not have the sharp outlines of Technicolor and why the colours look quite jaded. This could possibly be because the negative was in Gevacolor and only the prints in Technicolor. (imdb) Such hybrid printing is known as 'Color by Technicolor' and the credit titles of Mother India' (and Jhanak... and Navrang) accept as much. Incidentally, the credit titles of 'Aan' read 'Print by Technicolor.'

The 'Mother India' picture on this page is not at all typical of the quality of colours seen in that film. It is one of the very few scenes in that film that do not have a limited number of shades and colours. The colours of Mother India typically look like the 'Mother India' picture on the page:Indian cinema: 1950-59 (Indpaedia)

'Color by Technicolor' films are those that have used the post-production services of one of many film laboratories scattered across the globe and owned and operated by Technicolor. This laboratory would have developed, printed and transferred the film but no Technicolor format or printing would have been used. (Wikipedia)

The Technicolor era in Hindi-Urdu cinema came to an end with the box-office failure of Mera Naam Joker (1970). However, Raj Kapoor shot Satyam, Shivan, Sundaram (1978) in Eastmancolor and released some prints in Technicolor.

Technicolor vs. Eastmancolor...

...the difference to the naked eye

Mr and Mrs 55 have demonstrated (see the examples cited on this page) how superior the colours of Technicolor are, when compared to Eastmancolor, especially after a few decades. The original Mr and Mrs 55 site has twice as many such comparisons.

While Technicolor’s colours have, indeed, weathered more than a century of archiving better than any other known colour, sometimes SovColor (see the Pardesi images on this page) and Eastmancolor have done fairly well, too.

International collaborations

Two of India's earliest colour films were made in collaboration with other countries.

SovColor

The bilingual Indo-Soviet film Pardesi (1957) (Hindi-Urdu/ Russian/ dirs: Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Vasili Pronin/ 1957) was in SovColor, though no colour print of the Hindi-Urdu version is known to survive in India. The T Series DVD is in B&W. The film is called Хождение за три моря in Russian.

Written by Khwaja Ahmad Abbas and Mariya Smirnova, the film is the true story of the Russian trader Afanasi Nikitin (died 1472), who is the second known European (after Niccolò de' Conti) to have visited India (both the north and the Deccan) and have written about the land, its people and his journey. Russian actor Oleg Aleksandrovich Strizhenov played Afanasi.

The full film is available in B&W on [YouTube] in B&W. Its Censor Certificate states ‘Colour, Scope’ and gives the name of its filmmakers as ‘Meera Movies’ and ‘Son[?]a Sansar International.’

However, more excitingly, more than 25 minutes of the film are available in sharp, high quality colour and widescreen in the form of Hindi-Urdu songs [YouTube]. They have perhaps been taken from the Russian version in which the songs would have been in Hindi-Urdu. The music is by Anil Biswas. However, since the songs have not been subtitled, perhaps a colour print in Hindi-Urdu is available somewhere.

The naked eye will indicate i) how vastly superior SovColor was to all contemporary colours, except perhaps Technicolor (which had sharp details), and ii) how well the colours of this SovColor film have survived despite the lapse of more than fifty years.

Thailand

Angulimal (1960) was directed by Vijay Bhatt, starred only Indian actors,and was produced by the Thai Information Service Co. Ltd.

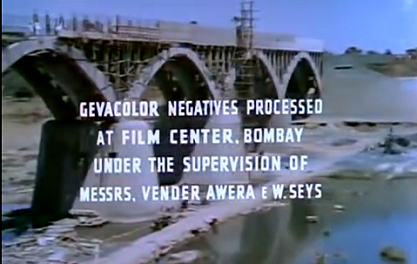

GevaColor

India had been making colour films since the 1930s. Every Technicolor and 'Color by Technicolor' film from Aan to Gunga Jumna (1961), except Jhansi ki Rani, had set new box office records. And yet colour did not catch on in India because only the top Moguls could afford Technicolor and only ‘A plus’-budget films could be made in Technicolor.

GevaColor changed things somewhat. It was so cheap that it took colour down not to the next lower rung of films, films that were merely ‘A budget,’ but straight to B and C films in Hindi-Urdu, and to the top rung of Tamil and Telugu cinema. (Many 'Color by Technicolor' films, eg Mother India, were shot in GevaColor.)

Sudhir informs us that Kishore Sahu's Mayur Pankh (1954) was the first GevaColor feature film to be released. Before that Pomposh (1954, a promotional film, funded by Film Centre, the importer of GevaColor raw stock) was made in Gevacolor and SHAHENSHAH (1953), was announced as to be shot in Gevacolor, but probably was not.’

(Since the 1990s India’s highest paid actor has generally been Rajinikanth, the Tamil superstar. The budgets of the top Tamil films sometimes exceed those of the top Hindi-Urdu film of that year. On some counts the Telugu film industry is huge. Since the mid-1980s technical firsts—notably 3D—have come from the South, in this case from Kerala. However, till at least the early 1970s the budgets of Hindi-Urdu films were vastly bigger.

(The MGR-starrer Alibabhavum Narpathu Thirudargalum (1955), the first Tamil (and first south Indian) colour film, was entirely in Gevacolor, while Nadodi Mannan (Tamil/ 1958) had some Gevacolor inserts. Lavakusa (1963), the first Telugu colour film, and an NTR-starrer, too, was in Gevacolor.)

Sudhir writes, ‘ Hatim Tai (1956) in GevaColor (produced by Wadia Brothers) was a very big hit.’ The film was, what in those days was called, a ‘fantasy film.’ Such films did not have A-list star casts and were the equivalent of today’s B or C films. Hattim Tai did have a certain following and made a profit considering its low budget, but it does not figure in IbosNetwork.com’s list of the top 11 hits of the year. It starred Jairaj and Shakila, neither a prominent actor.

Pyar Ki Pyas (1961), a B-budget family weepie and a flop, was in GevaColor and CinemaScope. Even in 1961 relatively few people were aware that such a film had been released.

The next GevaColor film in Hindi, Sampoorna Ramayan (1961), too, had a B-cast and a B-director, Babubhai Mistri. However, it was a hit because it encapsulated the most popular Hindu epic, The Ramayan, into 183 minutes, had lavish sets, special effects considered good at the time and some hit songs. True to the traditions of Old India, it was produced by a Parsi, Homi Wadia.

By then Eastmancolor had arrived. It was more expensive than GevaColor, more suitable for A list films than GevaColor and much cheaper than Technicolor.

Sudhir adds, ‘ Sachaa Jhutha (1970) was the last film that was shot and printed in GevaColor. The LP records were released by Polydor, which like Film Centre, the licencee of GevaColor products in India, was owned Mr. Ambalal Jhaverbhai Patel.’

Eastmancolor

Kapoor’s daughter Ritu Nanda would later write in her book Raj Kapoor Speaks (2002; page 69), “Mr George Gunn of Technicolor said, 'What tremendous production values your film has.’”

This confirms the widely held belief that Sangam was indeed in Technicolor.

Internationally

Eastman Kodak launched Eastmancolor, a colour print film that recorded colours better than any of its lower-priced competitors,in 1952. Apart from costs and quality, Eastmancolor offered convenience. Technicolor films had to be sent to Technicolor's own laboratories for the dye imbibition process. Eastmancolor let studios make prints using normal photographic processes.

In India

Hum Hindustani (1960/ by S. Mukerji for his own Filmalaya), an A film was entirely in Eastmancolor. It was an ‘above average’ success (Boxofficeindia). This began the democratisation of good quality colour in Hindi-Urdu cinema.

Hum Hindustani (1961), Sudhir points out, was the first Indian film in Eastmancolor, a colour technology that was less complex and, therefore, less expensive than Technicolor. On the other hand Eastmancolor was vastly more satisfying (Hum Hindustani’s titles described Eastmancolor as ‘glorious’) than the even cheaper Gevacolor and Orwocolor. (Fujicolor was the choppy and downmarket colour negative of the 1970s and early '80s. It was Souten [1983] that introduced India to the lavish, new Fujicolor, though Yeh Nazdeekiyan (1982), the year before, too, had indicated that Fujicolor had changed.)

Junglee (1961) was the first superhit in Eastmancolor, and jolted the nation’s attention towards this mid-priced but fairly high quality new colour film. Professor and Taj Mahal (both 1963) followed.

An American university website declares that Mahâbhârat (1965/ prod. AA Nadiadwala, dir: Babubhai Mistry) was in Technicolor. You know how seriously everyone (including us) takes American university documentation—indeed, several others have cited this one. However, the film’s own credits, in the almost mint Shemaroo print on youtube, clearly read ‘Eastmancolor.’

While trying to ascertain whether Mahâbhârat (1965) was in Technicolor or Eastman, this writer was pleasantly surprised to free the freshness of the colours of the opening sequences (see picture).

Pathécolour: What was it?

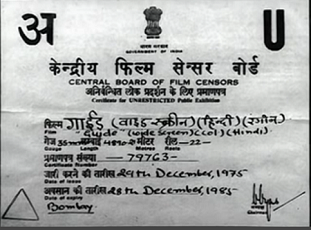

Dev Anand impressed a whole generation of cinegoers by using the offbeat Pathecolour in his Guide (1966). Cinegoers found subtle hues in Pathécolour that they felt were superior to the louder Eastmancolor. Pathécolour never resurfaced after that in Filmistan, except in Dev Anand-fan (and lieutenant) Amit Khanna’s Man Pasand (1980). However, those who decided to research what Pathecolour really was were disappointed to learn that in the context of these two films it was merely a posh, French-sounding brand name for Eastman Kodak's Eastmancolor colour negative film. It was a shattering moment for Indian cinephiles, on a par with Woody Allen’s discovery that the elbow patch on his venerable NYU professor’s tweed coat was not made of real leather.

(To top it all, Mr Anand claimed (and this was repeated in the film’s censor certificate) that the film was in ‘widescreen.’ Therefore, Indian cinegoers assumed that the film was either in CinemaScope or in 70mm. It was in neither. ‘Widescreen’ merely meant that Guide was in normal 35mm, but had a width-to-height aspect ratio greater than the normal 1.37:1, and that this ratio was achieved through ‘masking.’ The impact of Indian fans was like Mr. Allen being devastated by the knowledge that even the tweed of his professor’s jacket was fake. Allen would certainly have sought professional psychiatric help to deal with such a profound double blow.)

'Songs and dances in colour' vs. 'Tamaam rangeen'

In the 1950s,1960s and early 1970s many black and white films--including respected films by Satyajit Ray. K. Asif and Mrinal Sen of India, and A Tarkovsky of the USSR--had a few reels in colour. If such a film was Indian or Pakistani and of the commercial kind its posters would read 'Songs and dances in colour.'

If an Indian/ Pakistani film were 'entirely in colour' its local-level posters would, till even the late 1970s, mention this, even though by then B&W films had been gone for years. In North India the reassurance would read 'Tamaam rangeen' (entirely in colour).

‘Partly in colour’(colour inserts)

Moguls like Mehboob Khan, V. Shantaram and Sohrab Modi (who made films with prints in Technicolor) and producers of the next rung like Subodh Mukherji (Junglee/ 1961), FC Mehra (Professor/ 1962) and Shakti Samanta (Kashmir ki Kali/ 1964), all of who used Eastmancolor, had set a bold example. Almost all their colour films were enormously successful.

And yet even top budget films continued to be made in B&W till the mid-1960s. It is known that producer K. Asif made Mughal-e-Azam mostly in B&W because he could not afford a greater number of colour sequences. In the early 1960s the economics of colour films do not seem to have been very attractive, even though very few colour films had flopped. (The only colour flops were Jhansi ki Rani and Leader—both commercial; and Kisan Kanya, Pardesi (1957), Pyar ki Pyas and Son of India—all arthouse.)

Obviously because of high costs two of the Big Three stars, Raj Kapoor and Dev Anand, had their first entirely-in-colour films released as late as in 1964 and 1966 respectively. (In most of the 1960s Rajendra Kumar was arguably no.4 and Shammi Kapoor perhaps no.5, though by 1966 or so Rajendra ‘Jubilee’ Kumar was reportedly the highest paid star and remained so for a few years.)

Interestingly, even as Raj Kapoor and Dev Anand were soldiering on with B&W, not just Rajendra Kumar and Shammi Kapoor, but other A-list actors further down the pecking order had starred in major Eastmancolour films. Notable were Joy Mukherjee (also Phir Wohi Dil Laya Hoon/ 1963, Ziddi/1964), Biswajit (Shehnai/ 1964; Mere Sanam/ 1965) and Sunil Dutt (Khandan/1965, in addition to the multi-starrer Mother India).

Mahipal (Navrang/ 1959), Pradeep Kumar (Taj Mahal) and debutant Jeetendra (Geet Gaaya Pattharon Ne/ 1964) do not count because in their case the opulence of the film, and not their presence, justified the colour.

A few reels in colour was, thus, the compromise. These normally were reels with songs, dances and/ or spectacle. Even the Dev Anand-starrer Teen Devian (1965) included only some colour sequences. Pakistan’s superstar Waheed Murad’s Eid Mubarak (1965) was Pakistan's first film with a few colour scenes, even though (East) Pakistan had made an entirely-in-colour film the year before. (The same had happened in India: the ‘partly in colour’ trend came after films had been made entirely in colour.)

Nasir Hussain, a major producer-director, was one of the first to use colour. Phir Wohi Dil Laya Hoon (1963) was India’s fifth Eastmancolor film, and a hit. Teesri Manzil (1966), another success, followed in Eastmancolor. And yet as late as in 1967 he made Baharon Ke Sapne in B&W (with two sequences in colour) because it was a serious film about educated unemployed youths, and hence not likely to attract mass audiences.

In India the ‘partly in colour’ trend goes back at least as far back as Nagin (1954), a superhit B&W fantasy film with a few reels in Gevacolor. Nadodi Mannan (Tamil/ 1958), also a costume drama and fantasy film, included a colour sequence. Mughal-e-Azam (1960), the biggest-budget film of its time, had to include colour for the same reason: it was a historical spectacular and costume drama with ornate sets encrusted with faux gems.

Thus the ‘fantasy’ element was almost important as costs when it came to shooting a film in colour. It is notable that four of the first five 'print/ color by Technicolor' films in Hindi-Urdu; the first color by Technicolor film in Tamil and the first colour film in Telugu were all period films and costume dramas.

By the early 1960s the correlation between the budget of the film and colour weakened further. Bombay Ka Chor (1962) was a B&W, B-plus film. However, because audiences wanted colour its producers gratuitously included a colour sequence, quite unrelated to the film’s plot, called ‘Holiday on Ice.’ Such an unrelated insert would be billed as an "added attraction." Hawa Mahal (1962), a C-budget fantasy, was partly in colour.

When maestro Satyajit Ray made Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969/ Bengali), a fantasy film, he included some colour sequences. Left-leaning Mrinal Sen's Padatik (1973/ B&W/ Bengali) had one colour sequence about glitzy consmerism followed by and contrasted with shots of monochrome poverty.

Black and white films gradually lose out to colour

The megastar of the 1950s and the early ’60s, Dilip Kumar, did not act in a black and white film after 1961; the highest paid star of the mid-1960s, Rajendra Kumar, followed suit.

Increasingly the hits were all in colour and B&W films were seen as dull. Dosti (1964), a low budget weepie that touched the nation’s hearts, Haqeeqat (1964) and Shaheed (1965), both being patriotic films that stirred patriotic youths, were arguably the last Hindi-Urdu commercial successes in B&W. Dosti was a superhit.

Films delayed in the making

By the late 1960s the only black and white films featuring major actors were serious films meant for arthouses (e.g. the Raj Kapoor starrer Teesri Qasam (1967) and the Nargis-starrer Raat Aur Din/ 1967) or those that had got delayed in the making.

Shammi Kapoor was the actor associated with the success of Eastmancolor in India, and the star of the second, third and sixth Eastmancolor films, but even he had an A-category commercial black and white film Budtameez as late as in 1966. If the film received attention at all it was because of some great songs (Haseen ho tum, and Ooh lal la).

The Dev Anand starrer Kahin Aur Chal (1968) was perhaps the last A-list commercial Hindi-Urdu film in black and white. Even serious Dev Anand fans have not heard of Kahin Aur Chal.

The last commercial B&W films

Saraswatichandra (also 1968: famous for its songs), claimed on Wikipedia as the last B&W film in Hindi-Urdu, was a relatively low budget film and a literary, almost arthouse film. (See ‘Internet bloopers’ in this article.) Like Teesri Qasam and Raat aur Din before it, it took the better part of a year for Saraswatichandra to get a theatrical release after its completion--partly because all three films were unrelentingly serious and partly because they were in B&W. Distributors were reluctant to pick up such films, because they were certain to flop.

Commercial 'Bollywood movies,' albeit B-budget ones, continued to be made in B&W well after Saraswatichandra, which was not an A-budget film either. Bandish (1969: famous for Rafi’s classic song Abhi to raat baaqi hai), Simla Road (1969) and Priya (1970: starring Tanuja, famous songs: ‘She’s very pretty’ and ‘Garry Joe/ Gaye ja’) were all commercial entertainers, but in B&W.

B&W continues in arthouse films till the early 1970s

In the world of art films black and white continued into the early 1970s.

Even Dastak (1970), the last B&W film in Hindi-Urdu to make some money (by the micro-budget standards of art films), was not the last 'Bollywood movie' to be made in black and white, either. Art films like Sara Akash (1969), Uski Roti (1970), Khamoshi (1970: with an all-star cast from the world of commercial cinema--Dharmendra, Waheeda Rehman and Rajesh Khanna), Ashad Ka Ek Din (1971) and Ek Adhuri Kahani (1972) continued to be made in B&W well into the 1970s.

The great Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen were making B&W films in Bengali till the mid-1970s.

Art films have been in colour since at least Satyajit Ray’s Kanchanjangha (1962/ Bengali/ Eastmancolor), but then India’s greatest maestro had the world as his market. However, even he did not get back to an entirely-in-colour film for another 11 years, till 1973 (Ashani Sanket), after which he never went back to black and white. (Kanchanjangha is the spelling used on the cover of the DVD, but Kanchanjungha is the subtitle when the film's name, which is given only in Bengali, appears in the film itself.)

In Hindi-Urdu cinema, too, art films had been made in colour since Chetna (1970). However, it was Blaze films’ Eastmancolor Ankur (The Seedling) (1974), lavishly produced by the standards of Indian art cinema, that announced that art films need not be micro-budget. After that no Hindi-Urdu film, not even an art film, was made in black and white.

Colour films and success at the box office (1951-1970)

1951 was the year when India’s first commercially successful colour film was released. 1966 was the last year in the history of Hindi-Urdu cinema when there was a B&W film among the 20 highest grossing Hindi-Urdu films of the year.

Given below are the names of colour and ‘partly in colour’ films made between 1951 and 1964 and their performance at the box office relative to other Hindi Urdu films released that year. For 1965 and 1966 it is the names of B&W films that made it to the Top 20 that have been mentioned. The number shown after the name of each film denotes its rank in terms of box office success among the films released that year.

Figures and ranks for the 1950s have been taken fromIbos and for the 1960s from Boxofficeindia.

The box office rank of colour films (1951-1964)

1952 Aan 1 (the no. 1 hit of the year).

Jhansi Ki Rani was a flop. (Most histories list it among films released in 1952 [1] [2].

1953 No colour film released

1954 Nagin (partly in colour)No. 1

1955 Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baje No.5

1956 No colour film in Top 20.

Sudhir writes, ‘ Durgesh Nandini (1956) (produced by S. Mukerji for Filmistan) was a flop.’

1957 Mother India: no. 1

Sudhir writes,’ Champakali (1957) (Produced again by S. Mukerji for Filmistan) was probably a flop.’ (It was certainly not among the top earners.)

1958 Zimbo (1958) was, Sudhir writes, in GevaColor (produced by Wadia Brothers). It was another B or C film and successful for its low budget but was not among the Top 20. The VCD, released by Shemaroo is in B&W. The faintly coloured picture on this page is from the Bombino VCD.

1959 Navrang No. 4

1960 Mughal-e-Azam No.1 (partly in colour), Chaudvin Ka Chand No.4 (partly in colour), Hum Hindustani No.12 (entirely in colour)

1961 Ganga Jumna No.1, Junglee No.2

Mr Sudhir adds, ‘ Zabak (1961) in GevaColor (produced by Wadia Brothers) was a big hit and certainly a bigger grosser than Sampooran Ramayan.’ I am afraid it was not so. IbosNetwork.com’s list ranks Sampooran Ramayan as the 8th biggest hit of 1961. On the other hand, Zabak does not figure either among IbosNetwork.com’s Top 20 nor BoxOfficeIndia.com’s Top 18 Hindi-Urdu hits of 1961.

1962 Professor No.2 (ibos)/ 3 (boi)(Bees Saal Baad, B&W, was no.1)

1963 Mere Mehboob 1, Taj Mahal 2, Phir Bhi Wohi Dil Laya Hoon 3, Shikari 7 (a ‘B film’ did better than a major ‘A film’ like Mujhe Jeene Do mainly because it was in colour), Parasmani 17 (also a B or C film)

1964 Sangam 1, Ayee Milan Ki Bela 2, (Dosti, B&W, was no. 3), Ziddi 4, Rajkumar 5, Kashmir Ki Kali 6 (Haqeeqat 7, Zindagi 8, both B&W). April Fool 9. By 1964 colour had become commonplace, so colour films started doing badly, too: Leader was at no. 11 (below average earnings), Jahan Ara 16 (flop), Chitralekha 17 (flop: not only did it have colour but cheesecake, too, but audiences found it too serious).

The box office rank of B&W films (1965-1970)

1965 By 1965 the top 10 films were all in colour. And yet the B&W Shaheed was at 11 and the B&W Johar Mehmood in Goa at 13.

1966 Aasra 11 (B&W) was a ‘semi-hit,’ arguably the last commercial Hindi-Urdu film to make a profit at the box office.

1967 No B&W film in the Top 20.

1968 No B&W film made it to the Top 20.

1969 No B&W film made it to the Top 20.

1970 No B&W film made it to the Top 20.

Was there a relationship colour and box office success?

The relationship between a film being in colour and its success at the box office, it will be seen, is very strong, but not one hundred per cent. Well-made B&W films have, in a few cases, done better than colour films that were not equally good. And yet such films have been few and far between.

It is possible that colour films that did well were interesting films anyway. However, the correlation between colour and box office success in the initial years is so close to around 90 per cent that it would be too much of coincidence if colour films were also the best-made ones. This is seen from the fact that in the beginning colour was a bigger guarantor of success than after colour became commonplace. this is also seen from the fact that after 1966, when B&W films continued to be made in substantial numbers, no B&W film in Hindi-Urdu was in the Top 20.

Chaudhvin Ka Chand (1960) proves both points: a good film will do well anyway, even if not in colour, but colour improves whatever prospects it had anyway. It was initially released entirely in B&W and was a hit. Prints released later had two colour sequences (The Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema). Colour certainly enhanced the film’s appeal and prolonged its box office success, but the film would have done well anyway. [In the DVD of the film released by Yash Raj, only the title song is in colour. In the Eros DVD the title song as well as the mujra song “Kabhi Raaz e Muhabbat” are in colour. A B&W version of even the title song is available on YouTube.)

V. Shantaram’s color by Technicolor blockbusters Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baje and Navrang also prove both points. Had either film been in B&W, mass audiences would never have paid money to see a film without stars, without commercial entertainment and about something as serious as classical music and dance. They were clearly there for the colour and spectavle, but neither film let them down in terms of story either.

Shikari was a ‘B film’ or even a ‘C film’ but it did better than a major ‘A film’ like Mujhe Jeene Do mainly because it was in colour. Similarly, Parasmani, also a B or C film, entered the Top 20 partly because of hit music (it was music director-duo Laxmikant-Pyarelal’s debut film) and partly because of its few colour scenes.

Internet bloopers about Hindi-Urdu cinema

A crowdsourced article (Wikipedia) claims that Saraswatichandra (1968) was ‘the last Bollywood movie to be made in black and white.’ This is as untrue as other crowdsourced Internet myths such as that Kagaz ke phool was India’s first CinemaScope film (no, Pardesi (1957) was), or Sholay was India’s first 70mm film (Around the World was) or that Dev Anand’s Guide was released in 1965 (the summer of 1966 is the correct date) or that 'Jhansi ki Rani' was India's first film with a Technicolor print (Aan was).

See also

Binaca Geet Mala 1957: greatest hits

CinemaScope films in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka I.e. the first part of this article

70mm films in India/ South Asia

Cinerama theatres in India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka

Colour films in Hindi-Urdu

Mughal-e-Azam for the original Technicolor vs the colourised version.