China-India relations, 2000 onwards

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

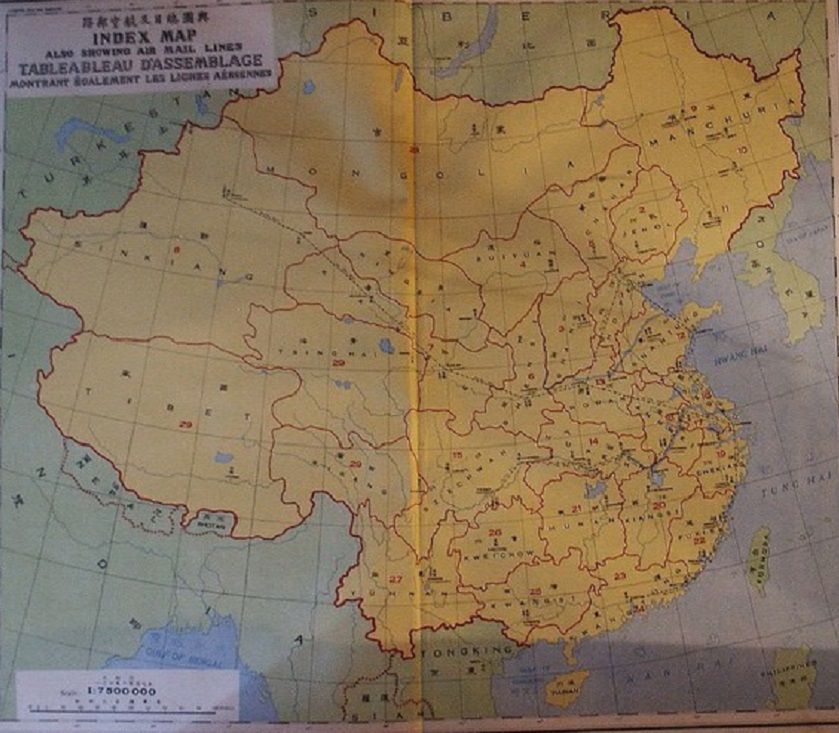

[[File: Postal Map of China , 1917.jpg| The ''Postal map of China'', 1917, an official publication of the Government of China, published in Peking in 1917, clearly shows Aksai Chin, Nepal, Sikkim and NEFA/ Tawang/ Arunachal Pradesh outside Chinese territory. <br/> This particular reproduction of the map has probably been taken from Dorothy Woodman’s ''Himalayan Frontiers '' (London, Barrie and Rockliff, The Cresset Press, 1969, page 81).|frame|500px]] | [[File: Postal Map of China , 1917.jpg| The ''Postal map of China'', 1917, an official publication of the Government of China, published in Peking in 1917, clearly shows Aksai Chin, Nepal, Sikkim and NEFA/ Tawang/ Arunachal Pradesh outside Chinese territory. <br/> This particular reproduction of the map has probably been taken from Dorothy Woodman’s ''Himalayan Frontiers '' (London, Barrie and Rockliff, The Cresset Press, 1969, page 81).|frame|500px]] | ||

| − | [[File: Postal Map of China, 1933a.jpg| From the ''Postal Atlas of China'', Nanking, Directorate General Posts, 1933. <br/> Apart from Aksai Chin and Tawang/ Arunachal Pradesh, please note how Doklam has been shown. <br/> Indpaedia wanted to make a nationalist point by | + | [[File: Postal Map of China, 1933a.jpg| From the ''Postal Atlas of China'', Nanking, Directorate General Posts, 1933. <br/> Apart from Aksai Chin and Tawang/ Arunachal Pradesh, please note how Doklam has been shown. <br/> Indpaedia wanted to make a nationalist point by showing how this map agreed with the official Indian position. We went to [http://www.soinakshe.uk.gov.in/ Survey of India’s Nakshe site] for the official Indian map. Twice we received OTPs and entered them, very carefully, twice each. Each time the site replied: ‘Invalid OTP.’ Obviously they are not keen to propagate the Indian national position.|frame|500px]] |

[[File: india china.jpg|A comparison of the economies of China and India on selected developmental parameters, as in Jan 2016; Graphic courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=A-REASON-TO-CELEBRATE-AS-INDIA-OVERTAKES-CHINA-09012016025037# ''The Times of India''] Jan 9 2016|frame|500px]] | [[File: india china.jpg|A comparison of the economies of China and India on selected developmental parameters, as in Jan 2016; Graphic courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=A-REASON-TO-CELEBRATE-AS-INDIA-OVERTAKES-CHINA-09012016025037# ''The Times of India''] Jan 9 2016|frame|500px]] | ||

Revision as of 20:09, 29 July 2017

This particular reproduction of the map has probably been taken from Dorothy Woodman’s Himalayan Frontiers (London, Barrie and Rockliff, The Cresset Press, 1969, page 81).

Apart from Aksai Chin and Tawang/ Arunachal Pradesh, please note how Doklam has been shown.

Indpaedia wanted to make a nationalist point by showing how this map agreed with the official Indian position. We went to Survey of India’s Nakshe site for the official Indian map. Twice we received OTPs and entered them, very carefully, twice each. Each time the site replied: ‘Invalid OTP.’ Obviously they are not keen to propagate the Indian national position.

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Ladakh and Arunachal

India Handed Dispute In Legacy

From the 2013 archives of The Times of India

Did India inherit the border dispute from the British?

The genesis lies in British efforts in the mid-1930s to annex territory in the Northeast to give India what ‘a strategic frontier’ [

What area were the Brits eyeing?

A sweep of territory at the edge of the Tibetan Plateau. The effort in 1914 failed, but in the 1940s the British moved into these areas

How did the Chinese react then?

They complained and complained against the British intrusions

Was the issue alive in 1947, when India became independent?

Yes. It was the first matter Nehru addressed as PM after he assumed offi ce

The Historic Address

On Nov 20, 1962, after Bomdila fell to Chinese soldiers, Nehru spoke on AIR. He said, “Huge Chinese armies have been marching in the northern part of NEFA. We have had reverses at Walong, Se La and Bomdila… We shall not rest till the invader goes out of India or is pushed out. I want to make that clear to all of you, and, especially our countrymen in Assam, to whom our heart goes out at this moment.” Many in Assam say the speech rankles to this day. They believe Delhi wasn’t really concerned about the Brahmaputra Valley. Nehru’s defenders insist he almost wept as he spoke. The speech was followed by virtual hysteria in Tezpur and many began fl eeing.

1950 : Patel cautions about China

Shiban Khaibri , Patel had cautioned Nehru on China "Daily Excelsior" 17/4/2017

Diplomacy with dexterity and political foresight cannot be in every politician’s kit. Nehru tried it hard though undoubtedly he had many abilities, but the results immediate and later, proved otherwise. Handling Kashmir and China proved Nehru wrong even during his life time, not to speak of, after his demise. There are people, including politicians who keep low profile and remain down to earth hence do not surface to the higher levels of due recognition , at least during their life time and awards, medals, prizes etc do not travel their way. To make the point clear, during NDA rule under Vjpayee Ji, we had George Fernandes as Defence Minister who in early 1998 had expressed the strong view that China was “potential threat No.1” and could become an enemy. This he had said in repetition even 10 years later on March 30, 2008. It will sound quite eerie that Sardar Patel, the veteran politician, one gifted with vision as well as strategies had cautioned Nehru about China way back in 1950, nearly a month before his passing away and that also through a detailed letter. 1962 Chinese invasion proved him prophetically right.

That China should “warn “India of mutual relations getting affected if it allowed Dalai Lama to visit Arunachal Pradesh sounds laced with sinister designs against our country. Strident protests by China against the visit of the octogenarian spiritual man to Arunachal Pradesh is nothing but a direct interference in our internal affairs. The Chinese media threatening and strangely so, that blows will be answered with blows, if “India plays dirty” should know that India has conventionally never played any dirty. India, at the same time, made it known to China assertively that Arunachal Pradesh was an inseparable part of India. Dalai Lama terms it a habit for Beijing to give political colour to his “spiritual visit”. China , it is learnt is proceeding with naming his successor while he has been reviewing for long in respect of the continuance of the institution of the Dalai Lama. He too seems to be scared of Chinese ire against his visiting Tawang which China is laying its claim over for quite some time when he feels that if Chinese representative could afford to “accompany” him , it would learn about his apolitical mission which confined to only religious ones. He appealed to China not to treat him as a separatist in the light of his “adopting a middle path”. Claiming Tibet to have very good relationship with China for thousands of years , he reiterates of having no issues with that country over “one China” policy wherein lay economic benefits of Tibet but only if they were allowed to “preserve our own culture and language”.

Had we antagonized China by giving asylum to Dalai Lama in March 1950 after it swooped on “Tibetian rebels”, killed thousands of them and demolished houses, bungalows etc of Dalai Lama and arrested hundreds of them? Was to that extent, not meddling in Tibetan matters, conforming to accepted international principles which Nehru in the burst of claiming champion of liberty and freedom, jumped over with long term ramifications ? There were many issues in run up to Tibetan “uprising” against Chinese onslaught in Tibet which the Sardar had smelt in advance as many as by 9 years. He wanted to share his feelings about our relations with China with Pandit Nehru in a cabinet meeting in 1950 but could not do as “the same was convened at a short notice of 15 minutes “. China had entered into a long correspondence with our External Affairs Ministry through our envoy in China and assured falsely about their good intentions .He told Nehru that Chinese government tried to delude us about their peaceful intentions. Patel felt and wrote to Nehru without mincing words that at a crucial juncture, the Chinese government tried to instill into the Indian ambassador a false sense of confidence in their so called desire to settle the Tibetan problem by peaceful means. The statesmanship acumen in the Sardar can be gauged by his foreseeing an event which was to unfold nearly a decade after the date of this letter (Nov 7, 1950) addressed to “My dear Jawaharlal”. He cautioned Nehru by saying, “There is no doubt that during the period covered by this correspondence, the Chinese must have been concentrating for an onslaught on Tibet, the final action of the Chinese in my judgment, is little short of perfidy.” Patel further had seen a lack of firmness and unnecessary apology in one of the two representations made by our the then ambassador to the Chinese government on our behalf. So much was the Iron Man of India blessed with the prowess of diplomatic intricacies that he could read between the lines too much which an ordinary politician and even “stalwarts” like Nehru could not. This letter in itself is a political document revealing more and hiding very less about how we were taken in by the mechanizations of a treacherous neighbor who like an enemy recently blocked our way to take benefit of international decision against a top terrorist in the world , a citizen of Pakistan and who has been declared as an international terrorist , at the same time warning this country of dire consequences in case we granted permission to Dalai Lama visit one of our own parts of the country, the Arunachal Pradesh.

The Sardar had cautioned Nehru not to treat China as our friend since China did not treat us one despite” Your direct approaches to them with the communist mentality of whoever is not with them is against them , this is a significant pointer of which we have to take a due note.” In 1950 shortly before his untimely death, the Sardar had predicted the real intentions of China and virtually pooh poohed Nehru’s out of box efforts to champion the cause of China internationally as he laments in his letter, “During the last several months, outside the Russian camp , we have been practically alone in championing the cause of Chinese entry in the UNO and in securing from the Americans assurances on the question of Formosa , we have done everything to assuage the Chinese feelings , to allay its apprehensions and to defend its legitimate claims in our discussions with America and Britain and in the UNO. In spite of this China continues to regard us with suspicion and the whole psychology is one , at least outwardly of scepticism, mixed with hostility.”

Patel underlines the fact as to how the North East had been neglected by the Nehru government and he is candid in bringing home to him , “Throughout History , we have been seldom worried about our North East frontier against any threat from the North , In 1914 we entered into a convention with Tibet , which was not endorsed by the Chinese ….recent and bitter history also tell us that communism is no shield against imperialism and that the communists are as good or as bad imperialists as any other.” He laid it bare perhaps for future historians and political analysts to find where we not only erred but committed blunders and he further told Nehru perhaps in the hope to have our relations with that country well defined and reviewed, “For the first time after centuries , India’s defence has to concentrate on two fronts simultaneously, our defence measures so far have been based on calculations of superiority over Pakistan but we shall have NOW to reckon with Communist China in the North and the North East , a communist China which has defence ambitions and aims and which does not in any way seem to be friendly with us.”

The letter is a valuable political treatise dealing on the one hand with our relations with China and second, our priorities and preparedness to confront two belligerent neighbours diplomatically and militarily. He had seen the internal threat to the country as well which he called “serious internal problems” . He writes to Nehru , ” Hitherto Communist Party of India has found difficulty in contacting the Communists abroad or in getting supplies of arms , literature and other help from them , they shall now have a comparatively easy means of access to Chinese Communists and through them to other foreign communists , infiltration of spies , fifth columnists and communists would now be easier.”

China attacked India in 1962 amidst sarcastic slogans “Hind Chinese Bhai Bhai” raised until only a few days before. Nehru and the entire defence preparedness were proved total incompatible and this political and diplomatic hari-kari upset Nehru beyond comprehension but each and every word of that born politician and statesman Sardar Patel proved prophetically correct. Yes, he had seen from China a tsunami in 1950 , say 12 years ago . Had he been alive , Nehru would have bowed before his political sagacity and felt remorseful for his political one-upmanship

Jeff Smith/ Foreign Policy on India’s China policy

New Delhi has been poking at Beijing's One-China Policy for years without wrecking the relationship

In an era when global powers are shunning both Taiwanese and Tibetan leaders (like the Dalai Lama) under the weight of Chinese pressure, one country has been openly challenging Beijing’s One-China policy for more than six years: India.

Like many of China’s neighbors, in the late 2000s India was still adjusting to the more assertive and nationalistic brand of Chinese foreign policy that emerged in 2008, when Beijing’s leaders interpreted the global financial crisis as symbolic of a great power shift from a declining West to an ascendant China. Bilateral ties were repeatedly tested by friction over Chinese incursions into India across their disputed border, Beijing’s efforts to block U.N. sanctions on Pakistan-based terrorists, and visits by the Indian prime minister and the Dalai Lama to the state of Arunachal Pradesh, most of which is claimed by China as “South Tibet,” among others.

One Chinese provocation cut deeper than the rest. In 2010, Beijing denied a visa to Lt. Gen. B.S. Jaswal on account of his posting as the head of India’s military command in Kashmir, the long-disputed territory claimed by China’s “all-weather friend” Pakistan. China had been employing consular chicanery with India for years — stapling separate, unique visas to Indian residents of Kashmir and Arunachal Pradesh as an informal challenge to Indian sovereignty there — but the denial of a visa to Jaswal struck a nerve.

New Delhi’s reaction was uncharacteristically swift and punitive, suspending all forms of bilateral military ties and joint exercises. When Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao visited New Delhi in December 2010, for the first time India refused to acknowledge the One-China policy in a joint statement with China. Beijing, New Delhi signaled, would have to recognize Indian sovereignty over Kashmir and Arunachal Pradesh if it wanted India’s consent on the One-China policy. “The ball is in their court. There is no doubt about that,” explained Foreign Secretary Nirupama Rao at the time.

Joint statements in the years to follow continued to omit the One-China policy, a position adopted by Prime Minister Narendra Modi when he assumed office in 2014. “For India to agree on a one-China policy, China should reaffirm a one-India policy,” External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj declared before Chinese President Xi Jinping’s first trip to New Delhi in September 2014. “When they raised the issue of Tibet and Taiwan with us, we shared their sensitivities.… They should understand and appreciate our sensitivities regarding Arunachal Pradesh.”

China relented on the visa question two years after Wen’s visit, and military ties were restored shortly thereafter. More important, six years after India’s change of heart on One-China policy, it has suffered no discernable political or economic backlash that can be tied to the policy shift.

To be sure, India’s denial of the One-China policy is less emotionally and politically contentious for China than any shift in American posture toward Taiwan. In the context of China-India relations, the One-China policy mostly relates to Tibet and, to a lesser extent, their long-standing border dispute, in which more than 30,000 square miles of Indian territory is still claimed by Beijing.

In 1947, the Republic of India inherited from the British Raj an unsettled border with China and a series of special trading privileges with Tibet, including the right to station escort troops at specified trading posts. Ever since China “peacefully liberated” Tibet in 1950, it has been critical of Indian intentions on the plateau and sensitive to Indian interference there. That anxiety was amplified after the Dalai Lama fled a Chinese crackdown in 1959 and sought refuge in India, later establishing a Tibetan government in exile in Dharamsala. After China and India fought a monthlong war across their disputed border in 1962, Chinese leaders argued that the “center of the Sino-Indian conflict” was not the border dispute but a “conflict of interests in Tibet.”

It’s notable, then, that beyond its broad refusal to endorse the One-China policy, New Delhi has given no indication that it plans to walk back its repeated reaffirmations of Chinese sovereignty over Tibet (much less Taiwan). On the other hand, Prime Minister Modi has adopted several initiatives short of that threshold to signal a more defiant posture on Tibet and the border dispute. Early in his tenure, for instance, Modi fast-tracked military and civilian infrastructure upgrades along the disputed Sino-Indian border, where Beijing has enjoyed a large and widening advantage.

More recently, New Delhi granted the Dalai Lama permission to visit Arunachal Pradesh in early 2017, a move that has drawn Chinese ire in the past. Perhaps most surprising, this past October New Delhi granted U.S. Ambassador to India Richard Verma access to the sensitive, Chinese-claimed town of Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh, another first. And just last week Indian President Pranab Mukherjee hosted the Dalai Lama at India’s Presidential Palace, blithely dismissing Beijing’s protesting diplomatic note. In a rare move, it even offered to help Mongolia weather trade sanctions recently imposed by Beijing as punishment for Mongolia’s hosting of the Dalai Lama in November. None of this has resulted in any direct punitive response from Beijing.

It’s not just Tibet, either. Since the visa denial incident in 2010, India has witnessed a marked acceleration in its outreach to Taiwan, including hosting several Taiwanese government ministers in 2011; signing new agreements on double taxation avoidance, cultural cooperation, and mutual degree recognition; permitting a former Taiwanese president and vice president transit layovers in 2012 and 2014, respectively; and inviting a former Taiwanese official to address two high-profile international conferences this year. These moves have yet to draw any sharp response from the mainland.

What does India’s approach to the One-China policy tell us about the Trump-Tsai phone call? Namely, that questioning the sanctity of the One-China policy is not necessarily a “death sentence” with Beijing, especially when the challenges are indirect and inexplicit. To date, China’s muted response to the phone call supports that assessment.

To Beijing’s mandarins, Modi represents an unfamiliar commodity: a confident, assertive, nationalist Indian leader with a surplus of political capital. The same is even truer for Trump, who, for China, remains shrouded in a cloak of uncertainty and unpredictability. China’s leadership isn’t nearly as confident that it can predict Trump’s response to each move on the regional chessboard, compared with Barack Obama’s more calculable style, and is naturally inclined to proceed cautiously. After years of testing the “red lines” of its neighbors and Washington as well, Beijing is not nearly as comfortable being on the receiving end.

As a party to more than a dozen meetings in Beijing and Washington with China’s current Taiwan affairs minister, Zhang Zhijun, and to numerous exchanges on Taiwan with some of China’s senior-most diplomats, I find it difficult to overstate the intensity and seriousness Beijing devotes to Taiwan and its status. It is far more sensitive to changes in America’s posture on One-China policy than India, partly because China has never felt particularly threatened by Indian power, and partly because its leadership has more directly linked its legitimacy to the reunification of Taiwan than to any issue related to Tibet.

Tomb of Xuanzang, who brought Buddhist scriptures from India, threatened

China to raze tomb of Buddhist monk with Indian links

From the archives of The Times of India

Saibal Dasgupta

April 13, 2013

Beijing: A portion of a temple that contains the remains of Xuanzang, the monk who brought Buddhist scriptures from India, is threatened with demolition.

The temple in Xian in north China contains the tomb of the monk, who played a key role in introducing Buddhism in China during the seventh century.

The local government in Chang’an in Xian claims it needs to clear a portion of the structure to strengthen the temple’s application for Unesco World Heritage status. It says it wants to remove buildings including a dining hall and a dormitory that were not part of the original 1300-year old temple, and were added in later years. Xuanzang and his Monkey King associate, Sun Wukong, are the heroes of the Chinese classic, “Journey to the West” that every Chinese child learns in school. The demolition is set to begin on June 30. But the move has sparked protests from monks and believers, who complain it was affecting their day to day worshipping. The Xingjiao temple, which is in the centre of the controversy has withdrawn its participation in the provincial government’s move to obtain the world heritage status. “If they demolish the buildings under the current plan, is it still possible that the application will be vetoed by the international panel,” temple spokesman Master Kuanshu told local journalists indicating he did not agree with the provincial government.

Initiatives

“One Belt One Road”

The Hindu, February 2, 2016

Samir Saran and Ritika Passi

China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ could potentially allow India a new track on its own attempt to integrate South Asia.

The central feature of much of the post-World War II American external engagement has been the security of its energy interests. Likewise, recent conversations with Chinese scholars, Communist Party of China members and officials indicate that the ‘One Belt, One Road’ (OBOR) initiative of Xi Jinping’s government is likely to become the lynchpin of Chinese engagement with the world. If, to understand American foreign policy of the years past, many have ‘followed the oil’, to decipher Chinese interests going forward, we may just have to ride the Belt and the Road.

At the third edition of the India-China Think-Tank Dialogue in Beijing, hosted in January 2016, a cross-section of Chinese scholars and officials discussed India-China relations and prospects for regional cooperation. The conversation cursorily engaged with the usual tensions in the bilateral relationship; instead, the centrepiece of all discussion was the OBOR initiative.

A Mandarin tale

Some facets of the new formulations that are giving shape to Beijing’s vision for OBOR and Asia could be discerned at this recent interaction.

The first was the novel idea of ‘entity diplomacy’. This construction argues for engaging within and across regions to secure the best interests of an entity that is necessarily larger and with interests broader than those of any sovereign. This follows from the argument of a revival of ‘continentalism’ as the Eurasian landmass deepens linkages and ‘Asia’ emerges. OBOR segues perfectly into this framework. It becomes, for the Chinese, an Asian undertaking that needs to be evaluated on the gains it accrues to the entity, i.e. Asia, as opposed to China alone. It therefore follows, from Beijing’s perspective, that Indian and other Asian nations must support and work for the OBOR initiative.

Entity diplomacy also translates into the establishment of “one economic continent”, the second theme undergirding the conversation. OBOR, then, becomes a vehicle that promotes alignment of infrastructure, trade and economic strategies. Indeed, for some Chinese speakers, India is already part of the initiative, as its own projects like Project Mausam and economic initiatives such as Make in India and Digital India complement and complete OBOR. Indian participation in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and joint ownership of the New Development Bank only reaffirm India’s partnership in this Asian project for many in Beijing.

To counter popular allegations of OBOR being a “Chinese scheme”, à la the U.S. Marshall Plan, the Chinese were quick to clarify that the original project is named the Belt and Road Initiative; the ‘One’ has been an English effect that has popularised a mien of exclusivity around OBOR, to the primary advantage of China, instead of an inclusive Asian economic project.

The third formulation was that of a mutually beneficial ‘swap’ — India protecting Chinese interests in the Indian Ocean, and China securing India’s essential undertakings in their part of the waters, read the South and East China Seas. However, there was unambiguous clarity that if India cannot assume more responsibility in the Indian Ocean, China will step in.

Core conflicts

Structural challenges confront the Chinese formulations and the OBOR proposal. First, the perception, process and implementation to date do not inspire trust in OBOR as a participatory and collaborative venture. The unilateral ideation and declaration — and the simultaneous lack of transparency — further weaken any sincerity towards an Asian entity and economic unity. The Chinese participants explained that Beijing is committed to pursuing wide-ranging consultations with the 60-plus nations OBOR implicates; an ‘OBOR Think Tank’ is also being established to engage scholars from these countries.

The second poser for the Chinese is on Beijing’s appetite for committing its political capital to the project. While for obvious reasons the Chinese would not want to be seen as projecting their military and political presence along OBOR, it was clear that China is willing to underwrite security through a collaborative framework.

The third challenge deals with the success of the ‘whole’ scheme, given that the Chinese vision document lays out five layers of connectivity: policy, physical, economic, financial and human. While no developing country will turn away infrastructure development opportunities financed by the Chinese, they may not necessarily welcome a rules regime built on a Chinese ethos.

Finally, how can this initiative navigate the irreconcilable geometries of South Asia that prevent India from providing full backing to OBOR? A formal nod to the project will serve as a de-facto legitimisation to Pakistan’s rights on Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) that is “closely related” to OBOR.

Options for India Fundamentally, New Delhi needs to resolve for itself whether OBOR represents a threat or an opportunity. The answer undoubtedly ticks both boxes. Chinese political expansion and economic ambitions, packaged as OBOR, are two sides of the same coin. To be firm while responding to one facet, while making use of the opportunities that become available from the other, will largely depend on the institutional agency and strategic imagination India is able to bring to the table.

First and foremost, India needs to match ambition with commensurate augmentation of its capacities that allows it to be a net security provider in the Indian Ocean region. This will require New Delhi to not only overcome its chronic inability to take speedy decisions with respect to defence partnerships and procurement, but will also necessitate a sustained period of predictable economic growth; OBOR can assist in the latter.

Therefore, just as U.S. trade and economic architecture underwrote the rise of China, Chinese railways, highways, ports and other capacities can serve as catalysts and platforms for sustained Indian double-digit growth. Simultaneously, India can focus on developing last-mile connectivity in its own backyard linking to the OBOR — the slip roads to the highways, the sidetracks to the Iron Silk Roads.

Arguably, OBOR offers India another political opportunity. There seems to be a degree of Chinese eagerness to solicit Indian partnership. Can India seek reworking of the CPEC by Beijing in return for its active participation? Furthermore, for the stability of the South Asian arm of OBOR, can Beijing be motivated to become a meaningful interlocutor prompting rational behaviour from Islamabad? OBOR could potentially allow India a new track to its own attempt to integrate South Asia.

India's stands on South China Sea

The Times of India, May 4, 2016

Indrani Bagchi

India's different stands on S China Sea lead to confusion

What exactly is India's position on the South China Sea? In two recent international joint statements, India has taken slightly different positions on the biggest point of international conflict that is about to come to a head in the coming days, leading to some confusion.

On April 18, foreign ministers of India, China and Russia stated after an RIC meeting in Moscow that “Russia, India and China are committed to maintaining a legal order for the seas and oceans based on the principles of international law, as reflected notably in the UN Convention on the Law of Sea (UNCLOS).All related disputes should be addressed through negotiations and agreements between the parties concerned. In this regard, the Ministers called for full respect of all provisions of UNCLOS, as well as the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) and the Guidelines for the implementation of the DOC.“

But just about a week ear lier, when US defence secretary Ashton Carter was in Delhi, a joint statement between him and Manohar Parrikar had this to say: US and India “reaffirmed the importance of safeguarding maritime security and ensuring freedom of navigation and overflight throughout the region, including in the South China Sea.They vowed their support for a rules-based order and regional security architecture conducive to peace and prosperity in the Asia-Pacific and Indian Ocean, and emphasised their commitment to working together and with other nations to ensure the security and stability that have been beneficial to the Asia-Pacific for decades.“

Both affirmations are slightly different, raising questions about what Indi a's actual position is. Sources said the RIC statement was in the context of a multilateral forum, but India's sovereign position will be clarified on the day the permanent court of arbitration pronounces its verdict.

China has declared in its state media outlets that India is sympathetic to China's view, and the RIC statement affirms it. Meanwhile, US Pacific Command chief, Admiral Harris indicated India and US may soon be sailing together for joint patrols, as part of a roadmap of the Strategic Vision document signed when Barack Obama visited India in 2015.

The official Chinese position was clarified by the charge d'affairs at the Chinese embassy here. Speaking to TOI, Liu Jinsong said, “We do not accept the jurisdiction in the South China Sea arbitration at the request of Philippines.The matter concerns China's territorial sovereignty , which is beyond the scope of UNCLOS. We can settle and manage the issue bilaterally through peaceful means based on international law, including UNCLOS.“