Champaran Satyagraha, 1917

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A book review, a backgrounder

MOHAMMAD SAJJAD, Sep 7, 2022: theindiaforum.in

From: MOHAMMAD SAJJAD, Sep 7, 2022: theindiaforum.in

From: MOHAMMAD SAJJAD, Sep 7, 2022: theindiaforum.in

From: MOHAMMAD SAJJAD, Sep 7, 2022: theindiaforum.in

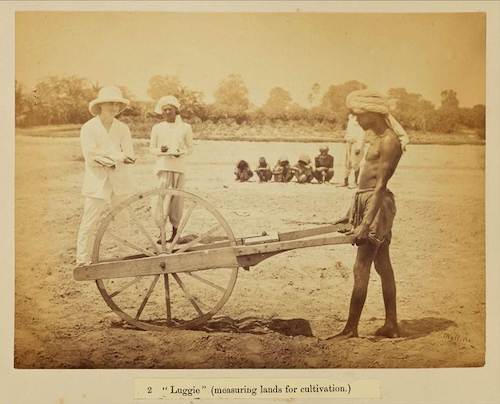

The Champaran Satyagraha of 1917 brought the miseries of the region’s peasants to official notice. A volume of 165 testimonies of peasants translated into English is revealing of their wretched lives, but many aspects of the struggle remain unexplored and there remain gaps in our understanding.

Since the 19th century, Champaran, the Bhojpuri-speaking region of north Bihar, in the foothills (terai) of the Himalayas, bordering Nepal, was seething with peasant discontent. The collusion of the Bettiah Raj (at the time one of the biggest zamindars of Bihar) with the European indigo planters (Nilaha Sahibs) was the main source of miseryfor the wretched peasants. In the 1860s and in 1907, there were two noticeable waves of resistance by the peasants under the leadership of the local intelligentsia, who mostly spoke in the vernacular.

It was only in April 1917, with the intervention of M.K. Gandhi, that the peasants’ voices were heard by the Raj. The Champaran Satyagraha that Gandhi led has immense significance in the history of India’s anti-colonial struggle. The ‘regional patriotism’ or ‘sub-national nationalism’ of Bihar acquired a pan-Indian nationalist identity in the ongoing anti-colonial struggle. Till then, Bihar’s articulate intelligentsia and elites (mostly English-educated Kayasthas and upper-caste Muslims) had been preoccupied with obtaining statehood for the region, which was then a part of Bengal. This had become a reality in 1912. It was with the Champaran Satyagraha that peasant question became integrated with the national movement.

Thumb Printed contains 165 testimonies, or recordings “of the statements of the aggrieved but fearful peasants” from the Bhojpuri-speaking villages of Champaran. These Bhojpuri-language documents—‘the small voice of history’—had been unexplored by professional historians.

This volume (7 more to come) of the Bhojpuri documents rendered into English now makes them accessible to a wider community of historians, scholars, and researchers than before. Butthis collection of testimonies is not meant to be read only by academics; they do have a popular appeal.

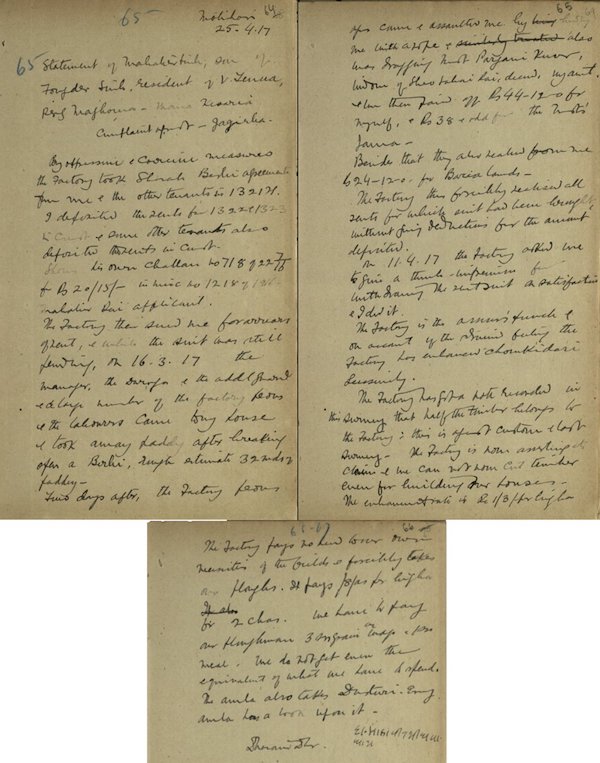

These Bhojpuri documents, “confessions wrenched in police lock-ups, depositions nervously uttered before Magistrates”, had been in the National Archives of India since 1973. These testimonies (izhar, bayan) include the caste composition and socio-economic status (quantum of landholding and other agricultural tools/assets) of the deponents, or the aggrieved peasants. One deposition is signed in English and many are in the local Kaithi script.All the testimonies are thumb printed, showing that the literacy level was low. At least three are signed by Gandhi. These testimonies were transcribed by Gandhi’s lawyer assistants and the statements were verified. In addition to being harrowing stories of exploitation of hapless peasants and landless labourers by European planters, these testimonies tell stories of the fraud and chicanery that peasants had to suffer at the hands of the Indian amlas (functionaries) of the planters.

Here are two of the testimonies included in the volume:

Statement of Musammat Rupia, widow of Dooman Mahto, daughter of Nakechhi Mahto, aged about 50 years, of village Banbirwa: This village is the zemendari of Bettiah Raj and is in Mukarrai [Mokarari = permanent lease] of the said Factory. I held land about 4 bigha 10 cottah with an annual income [jamabandi (illegible) rent] of Rs. 10/8/-. From 1320F I had to pay Rs. 16/8 for the said land owing to the enforcement of enhancement by the kothi. From last year the land has been taken away by the factory and settled with other person although protest was made by me. I being a woman could not do anything. I have two daughters and sons and one son’s wife to support. I am in much distress. I had the only land to support which has been taken away. The present survey and settlement is going on and the parcha given to me has been taken away by force by the factory amla. Motihari 10.5.1917 And another one: Statement of Mangra Chamar, son of Khubhari, aged 15 years, resident of Mowza Man Karania, Thana Gobindganj, under the Khairwa concern: I am a Chamar by caste. My holding is in the name of Jagroop Chamar, my grandfather. I am now in possession of only 2 ½ bighas of land in Man Karania and another 2 ½ bigha in Balua. I corroborate the statement made by Mahadeo Rai and others as regards compulsory execution of sarahbeshi. My further complaint is that from time immemorial it has been the custom, that when any cattle died in the village, it was the duty of the members of my family to remove the dead cattle and we were entitled to its skin. We had to supply in its stead country-made shoes to my co-villagers, free of cost, and to do other sundry works for them. We had also to pay Rs. 7/-only per year to the kothi for this monopoly. For the last seven years, after the dead cattle is skinned by us, it is forcibly taken to the kothi, and we get nothing in return for our labours. I am told, the kothi sells these skins. The kothi does not charge me Rs. 7/-per year since it takes the skins from us. I am in great difficulties these days, as I can’t supply shoes to my co-villagers, which my family had been doing. The rent of my holding viz. 5 bighas used to be Rs. 20/-only, now I have to pay Rs. 25/-only according to the sarahbeshi. Bettiah 9.5.1917

Besides the hitherto unattended documents/peasant testimonies, it is equally delightful to read the editorial/introductory essays. The 24-page “The Small Voices of History” by Shahid Amin, besides explaining in a glossary the terminology and expressions used by the local peasants, pertinently remarks, “These testimonies… speak for themselves. To forsake these peasant voices for a generalised politics of ‘Champaran Satyagraha’ would be to undercut the ground from under the feet of the Mahatma at the very moment of his making”. Amin’s glossary is a helpful guide to common as well as specialist readers.

The fairly well-researched, 29-page “Recording Voices, Inhabiting Champaran”, by Tridip Suhrud and Megha Todi, puts the whole story of the Satyagraha into its proper historical context. The concluding part of the editorial essay by Suhrud and Todi does hint at why the schools and ashrams launched by Gandhi failed to fulfil their roles, something even he was disappointed about. This awaits further exploration. The prefatory note of Chandan Sinha, the Director General, National Archives of India (NAI), gives us a succinct idea, a general overview, of the documents published in the volume under review.

One of the research-gaps or “inadequacies” pertaining to the Champaran Satyagraha has been that some of the significant local actors continue to remain under-acknowledged and under-explored. They include Master (school teacher) Harbans Sahay, Sheetal Rai, Sheikh Gulab (1858-1943), and even Pir Mohammad Munis (1882-1949) who findssome place in this collection of testimonies. There must be many more such names. Many of the significant memoirs, diaries, and correspondences of the better-known leaders of the movement have either omitted or downplayed some of the significant names associated with the satyagraha. Such accounts have also tried to conceal certain important facts about the classes and professions from which some of these people came.

For example, the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (CWMG, Vol. 15), deals with Gandhi’s stay in Patna and Muzaffarpur, on his way to Champaran in April 1917.Later, in January-February 1929, Gandhi recollected details of his initiatives and correspondences about the Satyagraha of 1917, and gave details about all these in CWMG, Vol. 44. In both these accounts, as well as in his autobiography, there is no mention of BatakhMiyan Ansari (1867-1957), who saved the lives of Gandhi and Rajendra Prasad. So is the case with Dr Rajendra Prasad, who accompanied Gandhi in 1917 to Champaran.This significant episode finds no space in his accounts, or even in J. B. Kripalani’s (1888-1982) memoir, My Times: An Autobiography, which was written in the 1970s, long after the British had gone, and was published posthumously in 2004.

Kripalani had the dubious distinction of remaining silent on many crucial issues he was expected to speak out on. In 1959, he was the member of Lok Sabha from Sitamarhi (then a subdivision of Muzaffarpur) and there was communal violence there. Yet, he chose to remain silent, even in the Lok Sabha. It was Nehru who spoke out, in one of his letters, which is a part of the U.N. Dhebar Papers.

Pir Mohammad Ansari “Munis” (1882-1949) has been sparingly acknowledged by Prasad, but not at all by Gandhi. Munis (son of Fatingan Miyan, a toddy seller) managed to get a smattering of education in Nagri-Hindi. That was an era when primary and secondary education in Persian was almost mainstream. Prasad (1884-1963) and many more went to maktabs and received their education in Persian. Despite this, from the late 19th century onwards, a Hindi-Urdu dispute acquired the overtones of a Hindu-Muslim conflict. In this scenario, Munis emerged as a Hindi writer and graced the sessions of the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan. Rather than writing about his religious identity, Munis chose to fight for his class identity. This in itself awaits exploration even while some of the towering nationalists have chosen to almost erase him out of their narratives. Fortunately, Ashutosh Partheshwar has compiled Munis’s reports and columns in his Hindi book, Champaran Andolan 1917(2020). Shahid Amin’s essay in Thumb Printed acknowledges this Hindi volume.

The better recognised name of Rajkumar Shukla (1875-1929) raises questions as to why the accounts of Gandhi, Rajendra Prasad, and Kripalani conceal that he was a moneylender who earned around Rs. 1,600 to Rs. 2,000 a month as interest from hisloans. This was stated by Shukla himself while deposing before the enquiry which was conducted by Gandhi.

A few more questions emerge about the historiographies of the Champaran Satyagraha. Why did Gandhi and his companions, who were upper-caste urban advocates of Patna and Muzaffarpur, as well as the likes of Shukla, leave the suffering peasantry of Champaran in the lurch? Why did Gandhi and the Congress choose to target the European indigo planters of Champaran, but leave out the more exploitative opium zamindars?

Again, why did Gandhi’s associates and companions in the Satyagraha lack the commitment and dedication to ameliorate the sufferings of the Champaran ryots? The lawyers and moneylenders such as Shukla belonged to a social stratum that gave no room to espousing the interests of the masses. The masses of Champaran—now divided into West and East Champaran districts—continue to languish. almost the same way as Gandhi saw them. How many times did Gandhi himself look back on the Champaran peasants in the 1930s and 1940s? The schools began by Gandhi could not remain open after 1917.

The grievances of the peasantry having been left unaddressed, they resurfaced soon after Independence in the form of the Saathi Land Agitation. During 1946-50, hundreds of acres of lands in Sathi (Champaran) were being settled in the names of various influential people (Arvind N. Das, 1983: pp. 223-25). Ram Manohar Lohia (1910-67) had enquired into this acquisition. . In their Hindi accounts and memoirs, peasant-activists such as Indradeep Sinha (Saathi Ke Kisanon Ka Aitihaasik Sangharsh, 1969), Ramnandan Mishra (Kisanon Ki Samasyayein, 1952) have written about the land loot in Saathi (Champaran). Gandhi and Sardar Patel asked the administration to cancel the settlements with Congress leader Prajapati Mishra, and Ram Prasad Shahi, an excise commissioner, and his brother. The Saathi Land Restoration Act was legislated in 1950. But the likes of Pir Munis and Batakh Miyan, remained landless. They died landless and poor even though the resistance of landless labourers under the leadership of the socialists and communists (moderate and radical) endured in Champaran and the rest of Bihar (for details, please see this essay.

In the decades following the Satyagraha, particularly during the last phase of colonialism, the Champaran hinterland and the then district headquarters. Motihari, witnessed a proliferation of communal organisations such as the Hindu Mahasabha and the Muslim League volunteer corps. There were many major and minor communal skirmishes in rural and urban Champaran. One of the worst was in early August 1927 in Bettiah town (then a subdivision headquarters, and now the headquarters of the district of West Champaran). In the 1920s, there was a spurt in the activities of the Tabligh and Tanzim movements, which were meant to promote Muslim prayers, organisation, and culture, and the Hindu counterparts to them, the Shuddhi and Sangathan movements, started by the Arya Samaj, to transform traditional religious identities into modern political ones. These were in the Champaran (Bihar) and the adjacent Gorakhpur parts of eastern Uttar Pradesh.

Communities such as the Magahiya Doms and the Malkana Rajputs, who claimed to have been converted to Islam, were reconverted back to Hinduism. These activities of competitive communalisation gained momentum while the schools and ashrams established by Gandhi and his associates in Champaran gradually folded up without having much effect on the conflicts and exploitations based on caste, gender, and religion.

Shahid Amin published a wonderful and influential account of Chauri Chaura and delved into how the memories of the Chauri Chaura violence (February 1922) continue to prevail among the people, decades after the event. A similar exploration of enduring popular memories of the Champaran Satyagraha needs to be undertaken by the historians or anthropologists.

Even with the publication of the testimonies in Thumb Printed, the gaps in our understanding of the Champaran Satyagraha will continue. This is something historians need to pay attention to. One hopes that the subsequent volumes will help us further reconstruct the story and will enable historians fill in the research-gaps.

Reading these documents take us into the lived realities of the wretched peasants tells us the story of how India was made into the republic by uniting people of all castes, religious communities, languages, to stand against the native and foreign oppressors. The freedom movement was not merely for the political freedom from the British. It was a fight for socio-economic emancipation of the masses and for institution building.

In our time when we are challenged with raging bigotry and communal hatred at the peril of our economic well-being, reading such a book of primary documents (peasant testimonies) is an even more purposeful and enriching exercise.

Mohammad Sajjad is Professor of History at Aligarh Muslim University.