Centre-State financial relations: India

This is a collection of newspaper articles selected for the excellence of their content. |

Contents[hide] |

Central grants to states: India

Centre kind to some, stingy with others

Odisha Tops Central Grants List

Subodh Varma TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

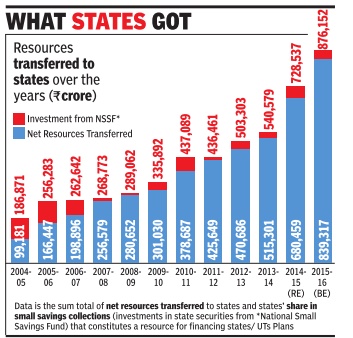

Every year, chief ministers make a beeline to the Planning Commission arguing for more allocation, bemoaning the cash crunch that state governments are facing.

So, how much funds does the central government actually give to the states?

Amounts vary according to the population of the states. So, comparing annual central grants may be misleading. For example, Tamil Nadu got over Rs 34,000 crore from the Centre between 2007-08 and 2011-12, while Kerala got less than half of that– Rs 15,000 crore. But that’s understandable – Kerala’s population is less than half of Tamil Nadu’s.

This problem is taken care of by looking at per capita grants from the Centre, that is, grants divided by population. Among major states, this throws up a strange and counter-intuitive picture. While some of the poorest states like Odisha, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh are top receivers of central funds, other poor or backward states like Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and West Bengal are among the lowest beneficiaries.

Between 2007-08 and 2011-12, Uttar Pradesh got just Rs 775 per head per year as grants from the Centre – the lowest among all major states. West Bengal, another populous and poverty stricken state, got Rs 984 per head per year.

Odisha topped the list among major states, getting Rs 1,688 – more than double of what UP got. Jharkhand (Rs 1,566) and Chhattisgarh (Rs 1,540) too got relatively more grants from the Centre. The national average for all states is Rs 1,423. But that includes transfers to states in the northeast, Jammu & Kashmir and other smaller states.

Broadly, total grants from the Centre to states fall in three categories – state plan schemes provided by the Planning Commission, central plan schemes and sponsored programmes provided by the central government, and non-plan grants provided by the Finance Commission, explains Subrat Das, head of New Delhi-based thinktank Center for Budget and Accountability (CBGA).

“Budgets approved for different states in a centrallysponsored scheme depend on priorities of the central ministries, assessment of needs across states, and ability and willingness of the state to contribute matching grants,” Das said. This could be one reason for the strange fact that some poor states seem to be getting more than others.

“Grants recommended by the Finance Commissions have been predominantly in the nature of general purpose grants meeting the difference between the assessed expenditure on the non-plan revenue account of each state and the projected revenue, including the share of a state in central taxes,” says Praveen Jha, professor of economics, and Atul K Singh, a research student at Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi.

Although ‘backwardness’ of a state was considered as a parameter for the first time in the Sixth Finance Commission (1973), the ‘gap-filling’ approach continued. It was only in recent finance commissions that some consideration to educational or health related parameters was given.

15th Finance Commission: report for 2020-21

February 2, 2020: The Times of India

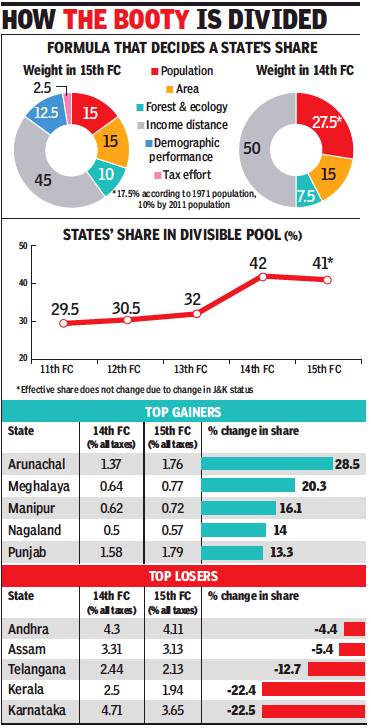

The states that gained and lost the most between the 14th and 15th Finance Commissions.

From: February 2, 2020: The Times of India

The 15th Finance Commission left the share of states in central taxes virtually unchanged for the next financial year, but its revamped formula for how the proceeds are allocated between states will result in significant gains for Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Arunachal Pradesh and Bihar. The southern states of Karnataka, Kerala, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh are the biggest losers.

The Constitution mandates that the Centre share the tax proceeds with the states, which also tap other revenue sources such as VAT on petrol and diesel, stamp duty and excise on alcohol. The formula for sharing revenues is decided by the Finance Commission every five years. This time, however, the 15th Finance Commission will decide the formula for six years.

Its report for 2020-21 was tabled in Parliament. The panel, headed by former bureaucrat and lawmaker NK Singh, is due to submit its final report later this year.

It has suggested that states be given 41% of the Centre’s net tax receipts during the next financial year, as against 42% for 2015-16 to 2019-20, arguing that the 1 percentage point change was on account of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh being converted into union territories. The share of the erstwhile state of J&K was estimated at 0.85% of the divisible pool. The 14th Finance Commission had increased the share of states from 32% to 42%.

A part of the change in the relative share of the states may be on account of the change in criteria and weights for what is called the horizontal devolution. Unlike its predecessor, the 15th Finance Commission has used the 2011 Census as the sole criteria for population but has reduced the weight for population to 15% from the earlier 27.5%. While retaining the 15% assigned to geographical area, it has enhanced the focus on forest and ecology from 7.5% to 10%.

It has also reduced the weight of income distance (how much lower or higher than the national average a state is) from 50% to 45% to provide higher devolution to the states with lower per capita income. Demographic performance and tax effort have been brought in as parameters to reward the states performing better on both these counts.

Through the new mix of parameters, the 15th Finance Commission has sought to address concerns that some of the states that had managed to control the pace of population expansion were being ‘penalised’ for this achievement.

Some of the Commission’s recommendations, including using the escape clause to trigger a half-apercentage point easing in the fiscal deficit target, have already been accepted. In fact, a few years ago, Singh headed a panel on Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act that had originally made a case for allowing the Centre to deviate from the fiscal consolidation plan in case of exceptional circumstances.

The Commission’s recommendation on performancebased incentives for agriculture have also been acted upon by finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman with states being encouraged to enact model laws on land leasing, agriculture produce and livestock marketing and contract farming to avail of grants from 2021-22.

There are a host of other reforms on which the 15th Finance Commission has prodded states to move — from reducing power sector losses to education and development of aspirational districts and blocks — indicating that it will offer incentives for the better-performing states through grants-in-aid when it presents its recommendations for the next five years.

For the time being, it has proposed special support for large cities such as Delhi to incentivise an improvement in air quality. The Commission has also recommended the creation of disaster mitigation funds at the central and state levels, which will be in addition to the disaster relief funds already in place.

Centrally sponsored schemes

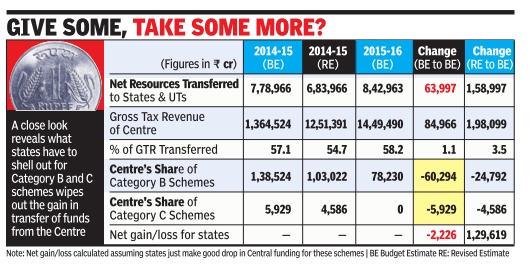

2015: Funding of 17 CSSs changed to 60:40

The Times of India, Akshaya Mukul, Nov 10 2015 Govt tweaks funding pattern of 17 key central schemes

In a major deci sion that could adversely af fect social sector schemes funding pattern of 17 central ly-sponsored schemes have been brought down to 60:40 between the Centre and states. This includes Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Midday Meal scheme, Swachch Bha rat Abhiyan, National Rura Drinking Water Programme Integrated Child Protection Scheme, Krishi Unnati Yojna Housing for All, Smart City Mission, National Health Mission, Atal Mission for Re juvenation and Urban Trans formation (AMRUT) and many others.

Funding pattern of Ma hatma Gandhi National Ru ral Employment Guarantee Scheme and six other schemes under National So cial Assistance Programme --an umbrella programme for development of SCsSTs differently abledminori tiesbackwards --have been left untouched.

Finance secretary Ratan P Watal has conveyed the decision to all administrative ministries. Watal said the decision has been taken based on the report of the subgroup of chief ministers on rationalization of centrallysponsored schemes constituted by the NITI Aayog.

Watal clarified that in case of 17 schemes if funding pattern is already less than 60:40, the existing funding pattern will continue. In case of Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS), he said, additional funds will be provided for this year at the supplementary stage. In case of Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojna finance ministry will issue separate instructions later. Many schemes not specifically mentioned, Watal said, will be optional for the state government and funding pattern will be 50:50 between the Centre and the states.

Four schemes, Watal said, will be run as central sector schemes from 2016-17. This in cludes National AIDS and STD Control Program, National Skill InitiativesSkill Development Mission under Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojna, National Disease Surveillance Systems and the Crime and Criminal Control Network. In case of Union Territories, centrally sponsored schemes will be 100% funded by the central government.However, which programme can run will be decided by the centre in consultation with union territory.

15th Finance Commission: report for 2020-21

February 2, 2020: The Times of India

The states that gained and lost the most between the 14th and 15th Finance Commissions.

From: February 2, 2020: The Times of India

The 15th Finance Commission left the share of states in central taxes virtually unchanged for the next financial year, but its revamped formula for how the proceeds are allocated between states will result in significant gains for Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Arunachal Pradesh and Bihar. The southern states of Karnataka, Kerala, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh are the biggest losers.

The Constitution mandates that the Centre share the tax proceeds with the states, which also tap other revenue sources such as VAT on petrol and diesel, stamp duty and excise on alcohol. The formula for sharing revenues is decided by the Finance Commission every five years. This time, however, the 15th Finance Commission will decide the formula for six years.

Its report for 2020-21 was tabled in Parliament. The panel, headed by former bureaucrat and lawmaker NK Singh, is due to submit its final report later this year.

It has suggested that states be given 41% of the Centre’s net tax receipts during the next financial year, as against 42% for 2015-16 to 2019-20, arguing that the 1 percentage point change was on account of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh being converted into union territories. The share of the erstwhile state of J&K was estimated at 0.85% of the divisible pool. The 14th Finance Commission had increased the share of states from 32% to 42%.

A part of the change in the relative share of the states may be on account of the change in criteria and weights for what is called the horizontal devolution. Unlike its predecessor, the 15th Finance Commission has used the 2011 Census as the sole criteria for population but has reduced the weight for population to 15% from the earlier 27.5%. While retaining the 15% assigned to geographical area, it has enhanced the focus on forest and ecology from 7.5% to 10%.

It has also reduced the weight of income distance (how much lower or higher than the national average a state is) from 50% to 45% to provide higher devolution to the states with lower per capita income. Demographic performance and tax effort have been brought in as parameters to reward the states performing better on both these counts.

Through the new mix of parameters, the 15th Finance Commission has sought to address concerns that some of the states that had managed to control the pace of population expansion were being ‘penalised’ for this achievement.

Some of the Commission’s recommendations, including using the escape clause to trigger a half-apercentage point easing in the fiscal deficit target, have already been accepted. In fact, a few years ago, Singh headed a panel on Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act that had originally made a case for allowing the Centre to deviate from the fiscal consolidation plan in case of exceptional circumstances.

The Commission’s recommendation on performancebased incentives for agriculture have also been acted upon by finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman with states being encouraged to enact model laws on land leasing, agriculture produce and livestock marketing and contract farming to avail of grants from 2021-22.

There are a host of other reforms on which the 15th Finance Commission has prodded states to move — from reducing power sector losses to education and development of aspirational districts and blocks — indicating that it will offer incentives for the better-performing states through grants-in-aid when it presents its recommendations for the next five years. For the time being, it has proposed special support for large cities such as Delhi to incentivise an improvement in air quality. The Commission has also recommended the creation of disaster mitigation funds at the central and state levels, which will be in addition to the disaster relief funds already in place.