Caste and the law: India

(→Held) |

(→Astrocities against Dalits) |

||

| Line 278: | Line 278: | ||

V.P.S. Appeal dismissed. | V.P.S. Appeal dismissed. | ||

| − | =Astrocities against Dalits= | + | =Astrocities against Dalits: The constitutional view= |

[http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/dalits-untouchable-rohith-vemula-caste-discrimination/1/587100.html ''India Today''], February 3, 2016 | [http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/dalits-untouchable-rohith-vemula-caste-discrimination/1/587100.html ''India Today''], February 3, 2016 | ||

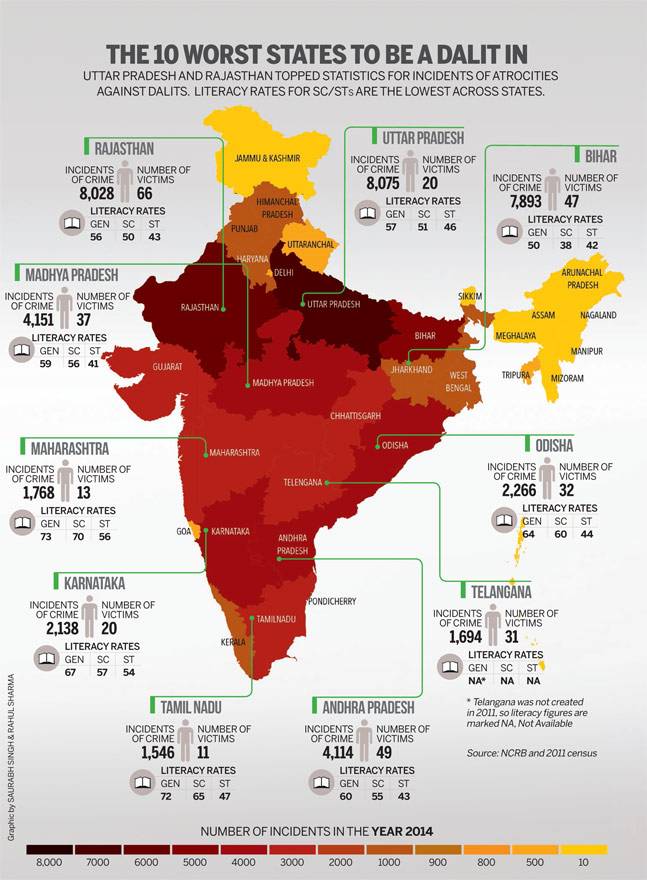

[[File: The 10 worst states for a dalit in India according to the number of incidents, 2014.jpg|The 10 worst states for a dalit in India according to the number of incidents, 2014; Graphic courtesy: [http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/dalits-untouchable-rohith-vemula-caste-discrimination/1/587100.html ''India Today''], February 3, 2016|frame|500px]] | [[File: The 10 worst states for a dalit in India according to the number of incidents, 2014.jpg|The 10 worst states for a dalit in India according to the number of incidents, 2014; Graphic courtesy: [http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/dalits-untouchable-rohith-vemula-caste-discrimination/1/587100.html ''India Today''], February 3, 2016|frame|500px]] | ||

| Line 333: | Line 333: | ||

Krishnan, on the other hand, believes that constitutional safeguards and protective legal clauses can play a great enabling role. But, more than any of this, a change of attitude is needed among the ruling classes to stem the tide. Perhaps the best solution was provided by B.R. Ambedkar in the Constituent Assembly. "We are entering an era of political equality. But economically and socially we remain a deeply unequal society. Unless we resolve this contradiction, inequality will destroy our democracy," he had warned. | Krishnan, on the other hand, believes that constitutional safeguards and protective legal clauses can play a great enabling role. But, more than any of this, a change of attitude is needed among the ruling classes to stem the tide. Perhaps the best solution was provided by B.R. Ambedkar in the Constituent Assembly. "We are entering an era of political equality. But economically and socially we remain a deeply unequal society. Unless we resolve this contradiction, inequality will destroy our democracy," he had warned. | ||

But nothing learnt; little progress made. The Dalit dilemma, ironically, is the dilemma of India. Some hard questions remain: How long must the discrimination continue? How many dreams must be shattered? How many flames of justice must be extinguished? How many Vaibhavs and Divyas must be burnt alive? How many Rohiths must die to change India, once and for all? | But nothing learnt; little progress made. The Dalit dilemma, ironically, is the dilemma of India. Some hard questions remain: How long must the discrimination continue? How many dreams must be shattered? How many flames of justice must be extinguished? How many Vaibhavs and Divyas must be burnt alive? How many Rohiths must die to change India, once and for all? | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==2013-15: State-wise atrocities against Dalits== | ||

| + | [http://m.thehindu.com/data/up-bihar-lead-in-crimes-against-dalits/article8894336.ece ''The Hindu''], July 25, 2016 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Vikas Pathak,G Sampath | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' U.P., Bihar lead in crimes against Dalits ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Data from Gujarat show such atrocities impossibly make up 163% of the total number of crimes. | ||

| + | Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Bihar lead the country in the number of cases registered of crimes against the Scheduled Castes, official data pertaining to 2013, 2014 and 2015 show. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The National Commission for Scheduled Castes (NCSC) counts these States among those deserving special attention. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | While U.P. has witnessed a political war of words over an expelled BJP leader's insulting remarks on BSP leader Mayawati, it is Rajasthan that leads in number of crimes against Dalits. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fifty-two to 65 per cent of all crimes in Rajasthan have a Dalit as the victim. This is despite the fact that the State's SC (Dalit) population is just 17.8 per cent of its total population. With six per cent of India's Dalit population, the State accounts for up to 17 per cent of the crimes against them across India. | ||

| + | |||

| + | With 20 per cent of India's Dalit population, U.P. accounts for 17 per cent of the crimes against them. The numbers — ranging from 7078 to 8946 from 2013 to 2015 — are high, but so is the population of Dalits in the State. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Bihar too has a poor track record, with 6721 to 7893 cases of atrocities in the same period, contributing 16-17 per cent of the all India crimes against Dalits with just eight per cent of the country's SC population. While Dalits form 15.9 per cent of the State’s population, 40-47 per cent of all crimes registered there are against Dalits. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Gujarat corrects figures''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gujarat on its part has shared corrected figures of crimes against Dalits with the NCSC after an abnormal increase in the figures pertaining to crimes against Dalits in the State. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The anamoly and sudden increase in respect to Gujarat and Chhattisgarh are abnormal and are being highlighted so that these States can provide actual data in case there was a mistake in reporting,” said the agenda note for the NCSC review meeting with the States last week. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gujarat's numbers of crimes against Dalits had jumped to 6655 in 2015 from 1130 in 2014, which made NCSC officials suspicious. There was also a statistical impossibility in the data — the crimes against Dalits were 163 per cent of the total number of crimes reported. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Gujarat officials corrected the data in the meeting, and these are like previous years,” an official present at the meet said. “Chhattisgarh officials have done the same.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gujarat's officials, sources said, were worried that “inflated” data would further damage the State's record on Dalit atrocities when at a time it is in the eye of storm over the Una incident of public beating of Dalits and the subsequent suicide attempts by Dalits in the state. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In an attempt at damage control, the Gujarat government has also released figures claiming crimes against Dalits in the State have “gone down” under the BJP. The corrected figure for 2015 in this data set is 1052, which is lower than figure for 2014. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The data also claim that while there were on an average 1669 crimes against Dalits per year in the State from 1991 to 2000, the number declined to 1098 between 2011 and 2015. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Atrocities''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | So far as the atrocities reported to the NCSC by Dalits who feel the authorities are not giving them justice are concerned, U.P. accounts for the highest number at 2024 cases and Tamil Nadu comes next at 999 cases. | ||

Revision as of 06:39, 25 July 2016

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Caste: can it be restored on re-conversion?

G. M. Arumugam vs S. Rajgopal & Others on 19 December, 1975

Supreme Court of India, Bench: Bhagwati, P.N.

Act

Constitution (Scheduled Castes) order, 1950, Paras 2 and 3 Adi Dravida, converted to Christianity and reconverted to Hinduism-If and when could be treated as Adi Dravida. When conversion affects caste. Code of Civil Procedure (Act 5 of 1908) s. 11-Res judicata-Decision about caste of`a candidate in one election petition if res-judicata when question arises in another later election.

Headnote

In the 1967 election to the State Legislative Assembly, the appellant and the 1st respondent claiming to be Adi Dravidas, stood as candidates for a seat reserved for Scheduled Castes. The respondent was declared elected. The appellant`s election petition challenging the election was allowed by the High Court. This Court dismissed the respondent's appeal holding,

(1) that the respondent was converted to Christianity in 1949, (2) that on such conversion he ceased to be an Adi Dravida, (3) that he was reconverted to Hinduism but 4) assuming that membership of a caste can be acquired on conversion or reconversion to Hinduism, the respondent had failed to establish that he became a member of the Adi Dravida caste after reconversion. In the 1972 elections, the appellant and respondent again filed their nominations as Adi Dravidas for the seat reserved for Scheduled Castes. On objection by the appellant, the Returning officer rejected the nomination of the respondent on the view that on conversion to Christianity, he ceased to be an Adi Dravida and that on reconversion, he could not claim the benefit of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) order, 1950.

The appellant was declared elected. The respondent challenged the election and the High Court held that the question (a) whether the respondent embraced Christianity in 1949, (b) whether on such conversion be ceased to be an Adi Dravida, and (c) whether he was reconverted to Hinduism, were concluded by the decision of this Court in the earlier case. In fact, the respondent so conceded on the first two aspects.

The High Court, however, held that the respondent had established twelve cir circumstances, which happened subsequent to the earlier election showing that he was accepted into their fold by the members of the Adi Dravida caste, that he was, therefore, at the material time, an Adi Dravida professing Hindu religion as required by paragraphs 2 and 3 of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) order, and that therefore, his nomination was improperly rejected. Dismissing the appeal to this Court, ^

Held

(1) The question whether the respondent abandoned Hinduism and embraced Christianity in 1949 is essentially a question of fact. The respondent having conceded before the High Court, that in view of the decision of this Court in the earlier case, the question did not survive for consideration and the High Court, having acted on that concession, the respondent could not be permitted to raise an argument that the evidence did not establish that he embraced Christianity in 1949. [89 D-F]

(2) Similarly. the question whether the respondent was reconverted to Hinduism stands concluded by the decision of this Court in the earlier case and it must be held that since prior to January 1967, the respondent was reconverted to Hinduism, he was, at the material time, professing the Hindu religion so as to satisfy the requirement of para 3 of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) order [94C-D]

(3) The High Court was right in the view that on reconversion to Hinduism, A the respondent could once again reconvert to his original Adi Deavida caste if he was accepted, as such, by the other members of that caste; and that, in fact, the respondent after his reconversion to Hinduism, was recognised and accepted as a member of the Adi Dravida caste by the other members of that community [97A-B, 98G]

(a) Since a caste is a social combination of person governed by its rules and regulations, it may, if its rules and regulations so provide, admit a new B. member just as it may expel an existing member. The rules and regulations of the caste may not have been formalised they may not exist in black and white: they may consist only of practices and usages.

If, according to the practice and usage of the caste any particular ceremonies are required to be performed for readmission to the caste, a reconvert to Hinduism would have to perform those ceremonies if he seeks readmission to the caste. But, if no rites or ceremonies are required to be performed for readmission of a person as a member of the caste, the only thing necessary would be the acceptance of the person concerned by the other members of the caste. [95 C-F] C

(b) The consistent view taken by the Courts from the time of the decision in Administrator General of Madras v. Anandachari (ILR 9 Mad. 466), that is, since 1886, has been that on reconversion to Hinduism, a person can once again become a member of the caste in which he was born and to which he belonged before conversion to another religion if the members of the caste accept him as a member.

If a person who has embraced another religion can be reconverted to Hinduism, there is no rational principle why he should not be able to come back to his caste, if the other members of the caste are prepared to re-admit him as a member. It stands to reason that he should be able to come back to the fold to which he once belonged, provided the community is willing to take him within the fold. [96 C-R] Nathu v. Keshwaji I.L.R. 26 Bom. 174.

Guruswami Nadar v. Irulappa Konar A.I.R. 1934 Mad. 630 and Durgaprasada Rao v. Sudarsanaswami, AIR 1940 Mad. 513, referred to. (c) It is the orthodox Hindu Society, still dominated to a large extent, particularly in rural areas, by medievalistic outlook and status-oriented approach which attaches social and economic disabilities to a person belonging to a Scheduled Caste and that is why, certain favoured treatment is given to him by the Constitution.

Once such a person ceases to be a Hindu and becomes a Christian the social and economic disabilities arising because of Hindu religion cease and hence, it is no longer necessary to give him protection; and for this reason, he is deemed not to belong to a Scheduled Caste. But, when he is reconverted to Hinduism. the social and economic disabilities once again revive and become attached to him, because, these are disabilities inflicted by Hinduism.

Therefore, the object and purpose of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) order would be advanced rather than retarded by taking the view that on reconversion to Hinduism, a person can once again become a member of the Scheduled Caste to which he belonged prior to his conversion. [96 F-97 A] (d) out of the 12 circumstances relied on by the High Court, 5 are not of A importance, namely, (1) that the respondent celebrated tho marriages of his younger brothers in the Adi Dravida manner; (ii) that the respondent was looked upon as a peace-maker among the Adi Dravida Hindus of the locality; (iii) that the funeral ceremonies of the respondent's father were performed " according to the Adi Dravida Hindu rites;

(iv) that he participated in the first annual death ceremonies of another Adi Dravida; and (v) that the respondent participated in an All India Scheduled Castes Conference.

The other seven circumstances, however, establish that the respondent was accepted and treated as a member of the Adi Dravida community, namely, (1) that he was invited to lay the foundation stone for the construction of the wall of an Adi Dravida temple:

(ii) that he was asked to take part in the celebrations connected with an Adi Dravida temple. (iii) that he was asked to preside at a festival connected with an Adi Dravida temple; (iv) that he was a member of the Executive Committee of the Scheduled Caste Cell in the organisation of the Ruling Congres; (v) that his children were registered in school as Adi Dravidas and that even the appellant had given a certificate that the respondent's son was an Adi Dravida.

(vi) that he was treated as a member of the Adi Dravida caste and was never disowned by the members of the caste; and

(vii) that a Scheduled Caste Conference was held in the locality with the object of re-admitting the respondent into the fold of Adi Dravida Caste and that not only was the purificatory ceremony performed on him at the Conference with a view to clearing the doubt which had been cast on his membership of the Adi Dravida caste by the earlier decision of this Court, but also an address was presented to him felicitating him on the occasion. [97 C-98 F]

(4)(a) The question whether on conversion to Christianity the respondent ceased to be a member of the Adi Dravida caste is a mixed question of law and fact and a concession made by him in the High Court on that question does not preclude him from re-agitating it in the appeal before this Court. r[89 G-H] (b) Further, the decision given in the earlier case relating to the 1967 elections on the basis of the evidence led in that case, cannot operate as res judicata ill the present case which relates to the 1972-election and where fresh evidence has been adduced by the parties and moreover, when all the parties in the present case are not the same as those in the earlier case. [89 H-90 B] (c) When a 'caste' is referred to in modern times, the reference is not to the 4 primary castes. but to the innumerable castes and sub-castes that prevail in Hindu society.

The general rule is that conversion operates as an expulsion from the caste, that is, a convert ceases to have any caste, because, caste is pre-dominantly a feature of Hindu Society and ordinarily a person, who ceases to be a Hindu, would not be regarded by the other members of the caste as belonging to their fold. But it is not an invariable rule that whenever a person renounces Hinduism and embraces another religious faith, he automatically ceases to be a member of the caste in which he was born and to which he be longed prior to his conversion.

Ultimately, it must depend on the structure of the caste and its rules and regulations whether a person would cease to belong to the caste on his abjuring Hinduism. If the structure of the caste is such that its members, must necessarily belong to Hindu religion, a member, who Ceases to be a Hindu, would go out of the caste, because, no non-Hindu can be in the caste according to its rules and regulations.

Where, on the other hand, having regard to its structure, as it has evolved over the years, a caste may consist not only of persons professing Hinduism but also persons professing some other religion as well, conversion from Hinduism to that other religion may not involve loss of caste, because, even persons professing that other religion ca be members of the caste.

This might happen where caste is based on economic or occupational characteristics and not on religious identity, or the cohesion of the caste as a social group is so strong that conversion into another religion does not operate to snap the bond between the convert and the social group. This is indeed not an infrequent phenomenon in South India, where, in some of the castes, even after conversion to Christianity, a person is regarded as continuing to belong to the caste.

What is, therefore, material to consider is how the caste looks at the question of conversion. Does it outcaste or excommunicate the convert or does it still treat him as continuing within its fold despite his conversion. If the convert desires and intends to continue as a member of the caste and the caste also continues to treat him as a member notwithstanding his conversion, he would continue to be a member of the caste, and the views of the new faith hardly matter.

Paragraphs 2 and 3 of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) order. read together. also recognise THAT there may be castes specified as Scheduled Castes which comprise persons belonging to a religion different from Hindu or Sikh religion. In such castes, conversion of a person from Hinduism cannot have the effect of putting him out of the caste, though. by reason of para 37 he would be deemed not to be a member of the Scheduled Caste. [90 F; 91 B-G; 93 C-E, F-H] Cooppoosami Chetty v. Duraisami Chetty, I.L.R. 33 Mad. 67; Muthusami v. Masilamani, I.L.R. 33 Mad. 342. G. Michael v. S. Venkateswaran. AIR 1952 Mad. 474. Kothapalli Narasayya v. Jammana Jogi, 30 E.L.R. 199; K. Narasimha Reddy v. G. Bhupathi, 31 E.L.R. 211; Gangat v. Returning Officer, [1975

1. S.C.C. 589 and Chatturbhuj Vithaldas Jasani v. Moreshwar Prasahram, [1954] A S.C.R. 817, referred to. [It would therefore, prima facie, seem that on conversion to Christianity, the respondent did not automatically cease to belong to the Adi Dravida caste; but in view of the decision that on reconversion he was readmitted to the Adi Dravida faith, no final opinion was expressed on this point.] [94 B-C] JUDGMENT: CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION: Civil Appeal No. 1171 of 1973. B From the judgment and order dated the 19th July, 1973 of the Mysore High Court at Bangalore in Election Petition No. 3 of 1972.

M. N. Phadke, M/s. N. M. Ghatate and S. Balakrishnan for the appellant. A. K. Sen, G. L. Sanghi, M/s. M. Veerappa and Altaf Ahmed for the respondents. The Judgment of the Court was delivered by

BHAGWATI, J.-This appeal under s. 116-A of the Representation of People Act, 1951 is directed against an order made by the High Court of Mysore setting aside the election of the appellant on the ground that the nomination paper of the 1st respondent was improperly rejected by the Returning officer. This litigation does not stand in isolation. It has a history and that is necessary to be noticed in order to appreciate the arguments which have been advanced on behalf of both parties in the appeal.

The appellant and the 1st respondent have been opponents in the electoral battle since a long time. The constituency from which they have been standing as candidates is 68 KGF Constituency for election to the Mysore Legislative Assembly. They opposed each other as candidates from this constituency in 1967 General Election to the Mysore Legislative Assembly. Now, the seat from this constituency was a seat reserved for Scheduled Castes and, therefore, only members of Scheduled Castes could stand as candidates from this constituency.

The expression "Scheduled Castes" has a technical meaning given to it by cl.(24) of Art. 366 of the Constitution and it means "such castes, races or tribes or parts Of or groups within such castes or tribes as are deemed under Art. 341 to be Scheduled Castes for the purpose of the Constitution". The President, in exercise of the power conferred upon him under Art. 341 issued the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) order, 1950. Paragraphs 2 and 3 of. this order are material and, since the amendment made by Central Act 63 of 1956, they are in the following terms:

"2.Subject to the provisions of this order, the castes, races or tribes or parts of, or groups within castes or tribes specified in Part I to XIII of the Schedule to this order shall, in relation to the States to which those parts respectively relate, be deemed to be scheduled castes so far as regards members thereof resident in the localities specified in relation to them in those Parts of that Schedule. 86

3.Notwithstanding anything contained in paragraph 2, no person who professes a religion different from the Hindu or the Sikh religion shall be deemed to be a member of a Scheduled Castes."

The Schedule to this order in Part VIII sets out "the castes, races or tribes or parts of or groups within castes or tribes" which shall in the different areas of the State of Mysore be deemed to be Scheduled Castes. We are concerned with cl. (1) of Part VIII as the area of 68 KGF Constituency is covered by that clause. One of the castes specified there is Adi Dravida and that caste must, therefore, for the purpose of election from 68 KGF Constituency, be deemed to be a Scheduled Caste. The appellant was admittedly, at the date when he Filed his nomination paper for the 1967 election from 68 KGF Constituency, an Adi Dravida professing Hindu religion and was consequently qualified to stand as a candidate for the reserved seat from this constituency.

The 1st respondent also claimed to be an Adi Dravida professing Hindu religion and on this basis, filed his nomination from the same constituency. The appellant and the 1st respondent were thus rival candidates-in fact they were the only two contesting candidates-r-and in a straight contest, the 1st respondent defeated the appellant and was declared elected.

The appellant thereupon filed election petition No. 4 of 1967 in the Mysore High Court challenging the election of the 1st respondent on the ground that the 1st respondent was not an Adi Dravida professing Hindu religion at the date when he filed his nomination and u-as, therefore, not qualified to stand as a candidate for the reserved seat from 68 KGF Constituency.

The Mysore High Court, by an order dated 30th August, 1967, held that the 1st respondent was converted to Christianity in 1949 and on such conversion, he ceased to be an Adi Dravida and, therefore, at the material date, he could not be said to be a member of a Scheduled Caste, nor did he profess Hindu religion and he was consequently not eligible for being chosen as a candidate for election from a reserved constituency.

The 1st respondent being aggrieved by the order setting aside his election, preferred C.A. No. 1553 of 1967 to this Court under s. 116A of the Representation of People Act, 1951. This Court addressed itself to four question, namely, first, whether the 1st respondent had become a convert to Christianity in 1949; secondly, whether, on such conversion, he ceased to be a member of Adi Dravida caste; thirdly, whether he had reverted to Hinduism and started professing Hindu religion at the date of filing his nomination, and lastly, whether on again professing the Hindu religion, he once again became a member of Adi Dravida caste.

So far as the first question was concerned, this Court, on a consideration of the evidence, held that the 1st respondent was converted to Christianity in 1949 and in regard to the second question, this Court observed that it must be held that when the 1st respondent embraced Christianity in 1949, he ceased to belong to Adi Dravida caste. This Court then proceeded to consider the third question and held that having regard to the seven circumstances enumerated in the judgment, it was clear that at the relevant time in 1967. that is in January-February 1967, the 1st respondent was professing Hindu religion. That led to a consideration of the last question as to the effect of reconversion of the 1st respondent to Hinduism.

This Court referred to a number of decisions of various High Courts which laid down the principle that reconversion to Hinduism, a person can become a member of the same caste in which he was born and to which he belonged before having been converted to another religion" , and pointed out that the main basis on which these decisions proceeded was that "if the members of the caste accept the reconversion of a person as a member,` it should be held that he does become a member of that caste, even though he may have lost membership of that caste on conversion to another religion".

This Court, however, did not consider it necessary to express any opinion on the correctness of these-decisions, as it found that even if the principle enunciated in these decisions was valid, the 1st respondent did not give evidence to t satisfy the requirements laid down by this principle and "failed to establish that he became a member of the Adi Dravida Hindu caste after he started professing the Hindu religion".

This Court observed that "whether the membership of a caste can be acquired by con version to Hinduism or after reconversion to Hinduism is a question on which we have refrained from expressing our opinion, because on the assumption that it can be acquired, we have arrived at the conclusion that the appellant"; that is, the 1st respondent in the present , case must fail in this appeal". This Court accordingly upheld the decision of the High Court and dismissed the appeal.(1) This decision was given by a Bench consisting of two judges on 3rd May, 1968. In the three or four years that followed certain events happened to which we shall refer a little later. Suffice it to state for the present that, according to the 1st respondent, these events showed that the members of the Adi Dravida caste accepted him as a member and regarded him as belonging to their fold.

The next General Election to the Mysore Legislative Assembly took place in 1972. There was again a contest from 68 KGF Constituency which was reserved for candidates from Scheduled Castes. The appellant filed his nomination as a candidate from this constituency and so did the 1st respondent. The nomination of the 1st respondent was, however, objected by the appellant on the ground that the 1st respondent was not an Adi Dravida professing Hindu religion at the date of filing his nomination and he was, therefore, not qualified to stand as a candidate for the reserved seat from this constituency.

The 1st respondent rejoined by saying that he was never converted to Christianity and that in any event, even if it was held that he had be" come a Christian, he was reconverted to Hinduism since long and was accepted by the members of the Adi Dravida caste as belonging to their fold and was, therefore, an Adi Dravida professing Hindu religion at the material date and hence qualified to stand as a candidate. The Returning officer, by an order dated 9th February, 1972 up held the objection of the appellant and taking the view that, on con version to Christianity, the 1st respondent ceased to be an Adi Dravida and thereafter on reconversion, he could not claim the benefit of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) order, 1950, the Returning officer (1) S. Rajagopal v. C.M. Arumugam, [1959] 1 S.C.R. 254. 7-L390 SCI/76 rejected the nomination of the 1st respondent. The election thereafter took place without the 1st respondent as a candidate and the appeliant, having obtained the highest number of votes, was declared elected.

The 1st respondent filed Election Petition No. 3 of 1972 in the High Court of Mysore challenging the election of the appellant on the ground that the nomination of the 1st respondent was improperly rejected. This was a ground under s. 100(1)(c) of the Act and if well founded, it would be sufficient, without more, to invalidate the election.

The point which was, therefore, seriously debated before the High Court was whether the nomination of the 1st respondent was improperly. rejected and that in its turn depended on the answer to the question whether the 1st respondent was an Adi Dravida professing Hindu religion at the date of filing his nomination.

There were four aspects bearing on this question which arose for consideration and they were broadly the same as in the earlier case (supra)., namely, whether the 1st respondent embraced Christianity in 1949, whether on his conversion to Christianity he ceased to belong to Adi Dravida caste, whether he was reconverted to Hinduism and whether on such reconversion, he was accepted by the members of the Adi Dravida caste as belonging to their fold.

So far as the first three aspects were concerned, the High Court took the view that they must be taken to be concluded by the decision of this Court in the earlier case (supra) and the discussion of the question must, therefore, proceed on the established premise that the Ist respondent was born an Adi Dravida Hindu, he was converted to Christianity in 1949 and on such conversion he lost his capacity as an Adi Dravida Hindu and at least by the year 1967, he had once again started professing Hindu religion. Visa-vis the fourth aspect, the High Court observed: "

It is settled law that reconversion to Hinduism does not require any formal ceremony or rituals or expiratory ceremonies, that a reconvert to Hinduism can revert to his original Hindu caste on acceptance by the members of that caste and that the quantum and degree of proof of acceptance depends on the facts and circumstances of each case, according to the established customs prevalent in a particular locality amongst the caste there", and on this view of the law, the High Court proceeded to examine the evidence led on behalf of the parties and pointed out that this evidence established twelve important circumstances subsequent to January-February 1967 which clearly showed that the 1st respondent was accepted into their fold by the members of the Adi Dravida caste and he was, therefore, at the material time, an Adi Dravida professing Hindu religion as required by Paragraphs 2 and 3 of the Constitution (Scheduled Caste) order, 1950.

The High Court, in this view, held that the nomination of the 1st respondent was improperly rejected by the Returning officer and that invalidated the election under s. 100(1)(c) of the Act. The High Court accordingly set aside the election of the appellant and declared it to be void. This judgement of the High Court is impugned in the present appeal under s. 116A of the Act.

Now before we deal with the contentions urged on behalf of the appellant in support of the appeal, it would be convenient first to refer to two grounds which were held by the High Court against the A 1st respondent. The 1st respondent contended that these two grounds were wrongly decided against him and even on these two grounds, he was entitled to claim that, at the material time, he was an Adi Dravida professing Hindu religion.

The first ground was that he was never converted to Christianity and the second was, that, on such conversion, he did not cease to be an Adi Dravida. The appellant disputed the claim' of the 1st respondent to agitate these two grounds in the appeal before us. The reason given was that the 1st respondent had not pressed them in the course of the arguments before the High Court and had conceded that, in view of the judgment of this Court in the earlier case, Issue No. 3, which raised the question: "Whether the petitioner having abandoned Hinduism and embraced Christianity in the year 1949 had lost the membership of the Adi Dravida Hindu caste and incurred the disqualification under Paragraph of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950" and "Is this issue concluded against the petitioner by virtue of the judgment of the High Court in Civil Appeal 1553 of 1967", did not survive for consideration.

There can be no doubt that so far as the first of these two grounds is concerned, there is force in the objection raised on behalf of the appellant. The question whether the 1st respondent abandoned Hinduism and embraced Christianity in 1949 is essentially a question of fact and if, at the stage of the arguments before the High Court, the 1st respondent conceded that, in view of the decision of this Court in the earlier case, this question did not survive for consideration and the High Court, acting on the concession of the 1st respondent, refrained from examining the question on merits and proceeded on the basis that it stood concluded by the decision of this Court in the earlier case, how could the 1st respondent be now permitted to reagitate this question at the hearing of the appeal before this Court ?

The 1st respondent must be held bound by the concession made by him on a question of fact before the High Court. We cannot, therefore, permit the 1st respondent to raise an argument that the evidence on record does not establish that he embraced Christianity in 1949.

We must proceed on the basis that he was converted to Christianity in that year The position is, however, different when we turn to the question whether, on conversion to Christianity, the 1st respondent ceased to be a member of the Adi Dravida caste. That question is a mixed question of law and fact and we do not think that a concession made by the 1st respondent on such a question at the stage of argument before the High Court, can preclude him from reagitating it in the appeal before this Court, when it formed the subject matter of an issue before the High Court and full and complete evidence in regard to such issue was led by both parties.

It is true that this Court held in the earlier case that, on embracing Christianity in 1949, the 1st respondent ceased to be a member of the Adi Dravida caste, but this decision given in a case relating to 1967 General Election on the basis of the evidence led in that case, cannot be res judicata in the present case which relates to 1972 General Election and where fresh evidence has been adduced on behalf of the parties, and more so, when all the parties in the present case are not the same as those in the earlier case. It is, therefore, competent to us to consider whether, on the evidence on record in the present case, it can be said to have been established that, on conversion to Christianity in 1949, the 1st respondent ceased to belong to Adi Dravida caste.

It is a matter of common knowledge that the institution of caste is a peculiarly Indian institution. There is considerable controversy amongst scholars as to how the caste system originated in this country. It is not necessary for the purpose of this appeal to go into this highly debatable question. It is sufficient to state that originally there were only four main castes, but gradually castes and sub-castes multiplied as the social fabric expanded with the absorption of different groups of people belonging to various cults and professing different religious faiths.

The caste system in its early stages was quite elastic but in course of time it gradually hardened into a rigid framework based upon heredity. Inevitably it gave rise to graduation which resulted in social inequality and put a premium on snobbery. The caste system tended to develop, as it were, group snobbery, one caste looking down upon another. Thus there came into being social hierarchy and stratification resulting in perpetration of social and economic injustice by the so-called higher castes on the lower castes.

It was for this reason that it was thought necessary by the Constitution makers to accord favoured treatment to the lower castes who were at the bottom of the scale of social values and who were afflicted by social and economic disabilities and the Constitution makers accordingly provided that the President may specify the castes and these would obviously be the lower castes which had suffered centuries of oppression and exploitation-which shall be deemed to be Scheduled Castes and laid down the principle that seats should be reserved in the legislature for the Scheduled Castes as it was believed and rightly, that the higher castes would not properly represent the interest of these lower castes. But that immediately raises the question: what is a caste? When we speak of a caste, we do not mean to refer in this context to the four primary castes but to the multiplicity of castes and sub-castes which disfigure the Indian social scene. "A caste", as pointed out by the High Court of Madras in Cooppoosami Chetty v. Duraisami Chetty (1) "is a voluntary association of persons for certain purposes." It is a well defined yet fluctuating group of persons governed by their own rules and regulations for certain internal purposes.

Sir H. Risley has shown in his book on People of India how castes are formed based not only on community of religion, but also on community of functions. It is also pointed out by Sankaran Nair, J., in Muthusami v. Masilamani(2): "a change in the occupation sometimes creates a new caste. A common occupation sometimes combines members of different castes into a distinct body which becomes a new caste. Migration to another place makes sometimes a new caste". A caste is more a social combination than a religious Group. But since, as

(1) I. L. R. 33 Mad. 67. (2) l. L. R. 33 Mad. 342. 91 pointed out by Rajamannar, C.J., in C. Michael v. S. Venkateswaran (1), ethics provides the standard for social life and it is founded ultimately on religious beliefs and doctrines, religion is inevitably mixed up with social conduct and that is why caste has become an integral feature of Hindu society. But from that it does not necessarily follow as an invariable rule that whenever a person renounces Hinduism and embraces another religious faith, he automatically ceases to be a member of the caste in which he was born and to which he belonged prior to his conversion.

It is no doubt true; and there we agree with the Madras High Court in C. Michael's case (supra) that the general rule is that conversion operates as an expulsion from the caste or, in other words, the convert ceases to have any caste, because caste is predominantly a feature of Hindu society and ordinarily a person who ceases to be a Hindu would not be regarded by the other members of the caste as belonging to their fold. But ultimately it must depend on the structure of the caste and its rules and regulations whether a person would cease to belong to the caste on his abjuring Hinduism.

If the structure of the caste is such that its members must necessarily belong to Hindu religion, a member, who ceases to be a Hindu, would go out of the caste, because no non-Hindu can be in the caste according to its rules and regulations. Where, on the other hand, having regard to its structure, as it has evolved over the years, a caste may consist not only of persons professing Hindu religion but also persons professing some other religion as well, conversion from Hinduism to that other religion may not involve loss of caste, because even persons professing such other religion can be members of the caste.

This might happen where caste is based on economic or occupational characteristics and not on religious identity or the cohesion of the caste as a social group is so strong that conversion into another religion does not operate to snap the bond between the convert and the social group. This is indeed not an infrequent phenomenon in South India where, in some of the castes, even after conversion to Christianity, a person is regarded as continuing to belong to the caste.

When an argument was advanced before the Madras High Court in G. Michael's case (supra) "that there were several cases in which a member of one of the lower castes who has been converted to Christianity has continued not only to consider himself as still being a member of the caste, but has also been considered so by other members of the caste who had not been converted," Rajamannar, C.J.,-who, it can safely be presumed, was familiar with the customs and practices prevalent in South India, accepted the position "that instances can be found in which in spite of conversion the caste distinctions might continue", though he treated them as exceptions to the general rule.

The High Court of Andhra Pradesh also affirmed in Kothapalli Narasayya v. Jammana Jogi(2) that "notwithstanding conversions, the converts whether an individual or family or group of converts, may like to be governed by the law by which they were governed before they became converts-and the community to which they originally H (1) A.I.R. 1952 Mad. 474. (2) 30 L. R. 1. belonged may also continue to accept them within their fold notwithstanding conversion", and proceeded to add: "While tendency to divide into sects and division to form new sects with their own religious and social observances is a characteristic feature of Hinduism-it should be remembered that sects were formed not only on community of religions but also community of functions. Casteism which has taken deep roots in Hinduism for some reason or other may not therefore cease its existence even after conversion. May be that the religion or faith to which conversion takes place, on grounds of policy or otherwise, does not take exception to this social order which does not interfere with its spiritual or theological aspect which is the main object of the religion.

That is why we find several members of lower castes converted to Christianity in Madras State-still continue to the members of their castes-Thus a conversion does not necessarily result in extinguishment of caste and notwithstanding conversion, a convert may enjoy the privileges social and political by virtue of his being a member of the community with its acceptance." The elected candidate in this case was held to continue to belong to the Mala Andhra Caste which was a Scheduled Caste, despite his conversion to Christianity. It was again reiterated by the High Court of Andhra Pradesh in a subsequent decision reported in K. Narasimha Reddy v. G. Bhupathi

(1) that survival of caste after conversion to Christianity is not an unfamiliar phenomenon in this part of the country and it was held that, even after his conversion to Christianity, the elected candidate, who belonged to Bindla caste, specified as a Scheduled Caste, continued to retain his caste, since he never abjured his caste nor did his caste people ostracize or excommunicate him. The caste system is indeed so deeply ingrained in the Indian mind that, as pointed out by this Court in Ganpat v. Returning Officer ,

(2) "for a person who has grown up in Indian society, it is very difficult to get out of the coils of the caste system" and, therefore, even conversion to another religion like Christianity, has in some cases no impact on the membership of the caste and the other members continue to regard the convert as still being a member of the caste. This Court pointed out in Ganpat`s case (supra) that "to this day one sees matrimonial advertisements which want a Vellala Christian bride or Nadar Christian bride" which shows that Vellala and Nadar comprise both Hindus and Christians.

lt seems that the correct test for determining this question is the one pointed out by this Court in Chatturbhuj Vithaldas Jasani v. Moreshwar Prasahram.(J) Bose, J., speaking on behalf of the Court in this case pointed out that when a question arises whether conversion operates as a break away from the caste "what we`have to (1) 31E.L.R.211. (2) [1975] 1 S.C.C. 589. (3) [1954] S.C.R. 817. determine are the social and political consequences of such conversion h that, we feel, must be decided in a common sense practical way rather than on theoretical and theocratic grounds". The learned Judge then proceeded to add:

"Looked at from the secular point of view, there are " three factors which have to be considered:

(1) the reactions of the old body, (2) the intentions of the individual himself and (3) the rules of the new order. If the old order is tolerant of the new faith and sees no reason to outcaste or ex-communicate the convert and the individual himself desires and intends to retain his old social political ties, the conversion is only nominal for all practical purposes and when we have to consider the legal and political rights of the old body, the views of the new faith hardly matter."

What is, therefore, material to consider is how the caste looks at the question of conversion. Does it outcaste or ex- communicate the convert or does it still treat him as continuing within its fold despite his conversion ? If the convert desires and intends to continue as a member of the caste and the caste also continues to treat him as a member, notwithstanding his conversion, he would continue to be a member of the caste and, as pointed out by this Court "the views of the new faith hardly matter". This was the principle on which it was decided by the Court in Chatturbhuj Vithaldas Jasani's case (supra) that Gangaram Thaware, whose nomination as a Scheduled Caste candidate was rejected by the Returning officer, continued to be a Mahar which was specified as a Scheduled Caste, despite his conversion to the Mahanubhav faith.

Paragraphs 2 and 3 of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) order, 1950 also support the view that even after conversion, a person may continue to belong to a caste which has been specified in the Schedule to that order as a Scheduled Caste.

Paragraph 2 provides that the castes specified in the Schedule to the order shall be deemed to be Scheduled Castes but Paragraph 3 declares that, notwithstanding anything contained in Paragraph 2, that is, notwithstanding that a per son belongs to a caste specified as a Scheduled Caste, he shall not be deemed to be a member of the Scheduled Caste, if he profess a religion different from Hindu or Sikh religion.

Paragraphs 2 and 3 read together thus clearly recognise that there may be castes specified as Scheduled Castes which comprise persons belonging to a religion different from Hindu or Sikh religion and if that be so, it must follow a fortiori, that in such castes, conversion of a person from Hinduism cannot have the effect of putting him out of the caste. though by reason of Paragraph 3 he would be deemed not to be a member of a Scheduled Caste.

It cannot, therefore, be laid down as an absolute rule uniformly applicable in all cases that whenever a member of a caste is converted from Hinduism to Christianity, he loses his membership of the caste. It is true that ordinarily on conversion to Christianity, he would cease to a member of the caste, but that is not an invariable rule.

It would depend on the structure of the caste and its rules and regulations. There are castes, particularly in South India, where this consequence does not follow on conversion, since such castes com prise both Hindus and Christians. Whether Adi Dravida is a caste which falls within this category or not is a question which would have to be determined on the evidence in this case.

There is on the record evidence of Kakkan (PW 13) J. C. Adimoolam (RW 1) and K. P Arumugam (RW 8), the last two being witnesses examined on behalf of the appellant, which shows. that amongst Adi Dravidas, there are both Hindus and Christians and there are intermarriages between them. It would, therefore, prima facie seem that, on conversion to Christianity, the 1st respondent did not cease to belong to Adi Dravida caste. But in the view we are taking as regards the last contention, we do not think it necessary to express any final opinion on this point.

The third question in controversy between the parties was whet her the 1st respondent was reconverted to Hinduism. This question stands concluded by the decision of this Court in the earlier case and it must be held, for the reasons set out in that decision, that at any rate since prior to January-February 1967, the 1st respondent was reconverted to Hinduism and, therefore, at the material time, he was professing the Hindu religion, so as to satisfy the requirement of Paragraph 3 of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) order, 1950.

The last contention, which formed the subject matter of controversy between the parties, raised the issue whether on reconversion to Hinduism, the 1st respondent could once again become a member of the Adi Dravida caste, assuming that he ceased to be such on conversion to Christianity. The argument of the appellant was that once the 1st respondent renounced Hinduism and embraced Christianity, he could not go back to the Adi Dravida caste on reconversion to Hinduism. He undoubtedly became a Hindu, but he could no longer claim to be a member of the Adi Dravida caste.

This argument is not sound on principle and it also runs counter to a long line of decided cases. Ganapathi Iyer, a distinguished scholar and jurist, pointed out as far back as 1915 in his well known treatise on 'Hindu Law': - "- caste is a social combination, the members of which are enlisted by birth and not by enrolment.

People do not join castes or religious fraternities as a matter of choice (in one respect); they belong to them as a matter of necessity ; they are born in their respective castes or sects. lt cannot be said, however, that membership by caste is deter. mined only by birth and not by anything else," (emphasis supplied) Chandravarkar, J., observed in Nathu v. Keshwaji(1): "It is within the power of a caste to admit into its fold men not born in it as it is within the power of a club to admit anyone it likes as its member. To hold that the membership of a caste is determined by birth is to (1) I. L. R. 26.Bom. 174.

hold that the caste cannot, if it likes, mix with another caste and form both into one caste. That would be striking at the very root of caste autonomy." Sankaran Nair, J., made observations to the same effect in Muthusami`s case (supra) and concluded by saying: "It is, of course, open to a community to admit any person and any marriage performed between him and any member would in my " opinion, be valid". Ganapathi Iyer, after referring to these two decisions, proceeded to add: Of course it is open to a person to change his caste by entering another caste if such latter caste will admit him-in this sense there is nothing to prevent a person from giving up his caste or community just as the caste may re-admit an expelled person or an outcasted person if he conforms to the caste observances." Since a caste is a social combination of persons governed by its rules and regulations, it may, if its rules and regulations so provide, admit a new member just as it may expel an existing member.

The rules and regulations of the caste may not have been formalised.: they may not exist in black and white: they may consist only of practices and usages. If, according to the practices and usages of the caste any particular ceremonies are required to be per formed for readmission to the caste, a reconvert to Hinduism would have to perform those ceremonies if he seeks readmission to the caste. That is why Parker, J., dealing with the possible readmission of a reconvert to Brahmanism observed in Administrator-General of madras v. Anandchari(1) :

"His conversion to Christianity according to the Hindu law, rendered him an outcaste and degraded. But according to that law, the degradation might have been atoned for, and the convert readmitted to his status as a Brahmin, had he at any time during his life renounced Christianity and performed the rites of expiation enjoined by his caste."

The rites of expiation were referred to by the learned Judge because they were enjoined by the Brahmin caste to which the reconvert wanted to be readmitted. But if no rites or ceremonies are required to be performed for readmission of a person as a member of the caste, the only thing necessary for eradication would be the acceptance of the person concerned by the other members of the caste. This was pointed out by Varadachariar, J., in Gurusami Nadar v. Irulappa Konar(2); where after referring to the aforesaid passage from Administrator-General of Madras v. Anandchari (supra), the learned Judge said:

"The language used in 9 Mad 466 merely refers to the expiatory ceremonies enjoined by the practice of the community in question; and with reference to the class of people we are now concerned with, no suggestion has anywhere been made in the course of the evidence that any particular expiatory ceremonies are observed amongst them. No particular ceremonies are prescribed for them by the Smriti writers nor have they got to perform any Homas. One has therefore only to look at the sense of the community and (1) I. L. R. 9 Mad. 466. (2) A. I. R. 1934 Mad. 630 . 96 from that point of view it is of particular significance that the community was prepared to receive Vedanayaga and defendant 5 as man and wife and their issue as legitimate."

These observations of Varadachariar, J., were approved by Mockett, J., in Durgaprasada Rao v. Sudarsanaswami(1) and he pointed out that in the case before him, there was no evidence of the existence of any ceremonial in Vada Baligi fishermen community of Gopalpur for readmission to that community. Krishnaswami Ayyangar, J., also observed in the same case that "in matters affecting the well being or composition of a caste, the caste itself is the supreme judge". (emphasis supplied). The same view has also been taken in a number of decisions of the Andhra Pradesh and Madras High Courts in election petitions arising out of 1967 General Election. These decisions have been set out in the judgment of this Court in Rajagopal v. C. R. Arumugam (supra).

These cases show that the consistent view taken in this country from the time Administrator-General of Madras v. Anandachari (supra) was decided, that is, since 1886 has been that on reconversion to Hinduism, a person can once again become a member of The caste in which he was born and to which he belonged before con version to another religion, if the members of the caste accept him as a member. There is no reason either on principle or on authority which should compel us to disregard this view which has prevailed for almost a century and lay down a different rule on the subject. If a person who has embraced another religion can be reconverted to Hinduism, there is no rational principle why he should not be able to come back to his caste, if the other members of the caste are pre pared to readmit him as a member.

It stands to reason that he should be able to come back to the fold to which he once belonged, provided of course the community is willing to take him within the fold. It is the orthodox Hindu society still dominated to a large extent, particularly in rural areas, by medievalistic outlook and status oriented approach which attaches social and economic disabilities to a person belonging to a Scheduled Caste and that is why certain favoured treatment is given to him by the Constitution. Once such a person ceases to be a Hindu and becomes a Christian, the social and economic disabilities arising because of Hindu religion cease and hence it is no longer necessary to give him protection and for this reason he is deemed not to belong to a Scheduled Caste. But when he is reconverted to Hinduism, the social and economic disabilities once again revive and become attached to him because these are disabilities inflicted by Hinduism.

A Mahar or a Koli or a Mala would not be recognised as anything but a Mahar or a Koli or a Mala after reconversion to Hinduism and he would suffer from the same social and economic disabilities from which he suffered before he was converted to another religion. It is, therefore, obvious that the object and purpose of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) order, 1950 would be advanced rather than retarded by taking the view that on (1) A.I.R. 1940 Mad. 513.

reconversion to Hinduism, a person can once again become a member of the Scheduled Caste to which he belonged prior to his conversion. We accordingly agree with the view taken by the High Court that on reconversion to Hinduism, the 1st respondent could once again revert to his original Adi Dravida caste if he was accepted as such by the other members of the caste. That takes us to the question whether in fact the 1st respondent was accepted as a member of the Adi Dravida caste after his reconversion to Hinduism. This Court in the earlier decision between the parties found that the 1st respondent had not produced evidence to show that after his reconversion to Hinduism, any step had been taken by the members of the Adi Dravida caste indicating that he was being accepted as a member of that caste. The 1st respondent, therefore, in the present case, led considerable oral as well as documentary evidence tending to show that subsequent to January-February 1967, the 1st respondent had been accepted as a member of the Adi Dravida caste.

The High Court referred to twelve circumstances appearing from the evidence and held on the basis of these twelve circumstances, that the Adi Dravida caste had accepted the 1st respondent as its member and he accordingly belonged to the Adi Dravida caste at the material time. Now, out of these twelve circumstances, we do not attach any importance to the first circumstance which refers to the celebrations of the marriages of his younger brother Govindaraj and Manickam by the 1st respondent in the Adi Dravida manner, because it is quite natural that if Govindaraj and Manickam were Adi Dravida Hindus, their marriages would be celebrated according to Adi Dravida rites and merely because the 1 st respondent, as their elder brother, celebrated their marriages, it would not follow that he was also an Adi Dravida Hindu.

The second circumstance that the 1st respondent was looked upon as a peacemaker among the Adi Dravida Hindus of K.G.F. cannot also be regarded as of much significance, because, if the Ist respondent was a recognised leader, it is quite possible that the Adi Dravida Hindus of K.G.F. might go to him for resolution of their disputes, even though he himself might not be an Adi Dravida Hindu. But the third, fourth and fifth circumstances are of importance, because, unless the 1st respondent was recognised and accepted as an Adi Dravida Hindu, he would not have been invited to lay the foundation stone for the construction of the new wall of the temple of Jambakullam, which was essentially a temple of Adi Dravida Hindus, nor would he have been requested to participate in the Maroazhi Thiruppavai celebration at the Kannabhiran Temple situate at III Line, Kennedy Block, K.G.F., which was also a temple essentially maintained by the Adi Dravida Hindus and equally, he would not have been invited to preside at the Adi Krittikai festival at Mariamman Temple in I, Post office Block, Marikuppam, K.G.F. where the devotees are Adi Dravidas or to start the procession of the Deity at such festival.

These three circumstances are strongly indicative of the fact that the 1st respondent was accepted and treated as a member by the Adi Dravida community. So also does the sixth circumstance that the 1st respondent was a member of the Executive Committee of the Scheduled Caste Cell in the organisation of the Ruling Congres indicate in the same direction.

The seventh and eighth circumstances are again of a neutral character The funeral ceremonies and obsequies of the father of the 1st respondent would naturally be performed according to the Adi Dravida Hindu rites if he was an Adi Dravida Hindu and that would not mean that the 1st respondent was also an Adi Dravida Hindu. Similarly, the fact that the 1st respondent participated in the first annual ceremonies of the late M. A. Vadivelu would not indicate that the 1st respondent was also an Adi Dravida Hindu like late M. A. Vadivelu. But the ninth circumstance is again very important. It is significant that the children of the 1st respondent were registered in the school as Adi Dravida Hindus and even the appellant himself issued a certificate " stating that R. Kumar, the son of the 1st respondent, was a Scheduled Caste Adi Dravida Hindu.

The tenth circumstance that the first respondent participated in the All India Scheduled Castes Conference at New Delhi on 30th and 31st August, 1968 may not be regarded as of any particular importance. It would merely indicate his intention and desire to regard himself as a member of the Adi Dravida Caste.

The eleventh circumstance is, however, of some importance, because it shows that throughout the 1st respondent was treated as a member of the Adi Dravida Caste and he was never disowned by the members of that caste. They always regarded him as an Adi Dravida belonging to their fold. But the most important of all these circumstance is the twelfth, namely, the Scheduled Caste Conference held at Skating Rink, Nundydroog Mine, K.G.F. On 11th August. 1968. The High Court has discussed the evidence in regard to this conference in some detail. We have carefully gone through the evidence of the witnesses on this point, but we do not find anything wrong in the appreciation of their evidence by the High Court. We are particularly impressed by the evidence of Kakkan (PW 13).

The cross- examination of J. C. Adimoolam (RW 1) is also quite revealing. We find ourselves completely in agreement with the view taken by the High Court that this conference, attended largely by Adi Dravida Hindus, was held on 11th August, 1968 inter alia with the object of re-admitting the 1st respondent into the fold of Adi Dravida caste and not only was a purificatory ceremony performed on the 1st respondent at this conference with a view to clearing the doubt which had been cast on his membership of the Adi Dravida caste by the decision of this Court in the earlier case but an address Ex. P-56 was also presented to the 1st respondent felicitating him on this occasion. It is clear from these circumstances, which have been discussed and accepted by us, that after his reconversion to Hinduism, the 1st respondent was recognised and accepted as a member of the Adi Dravida caste by the other members of that community.

The High Court was, therefore, right in coming to the conclusion that at the material time the 1st respondent belonged to the Adi Dravida caste so as to fall within the category of Scheduled Castes under Paragraph 2 of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) order, 1950. In the result the appeal fails and is dismissed with costs. V.P.S. Appeal dismissed.

Astrocities against Dalits: The constitutional view

India Today, February 3, 2016

Ajit Kumar Jha

68 years after Independence, political rhetoric and Constitutional protection have failed to end atrocities against Dalits. Is Ambedkar's dream of social and economic equality a bridge too far?

"The State shall promote with special care the educational and economic interests of the weaker section of the people, and in particular, of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation."

-Article 46 of the Indian Constitution.

Today, 68 years after Independence, as Dalits continue to bear the brunt of violence and discrimination-highlighted in recent weeks by the tragic suicide of Rohith Vemula, a Ph.D student in the Hyderabad Central University who hanged himself, blaming his birth as a "fatal accident" in a chilling final note-we could not be any further away from what the Constitution had demanded from a free and fair India.

Rohith's is not the lone tragedy. A spectre of suicide deaths by several Dalit students is haunting India. Out of 25 students who committed suicide only in north India and Hyderabad since 2007, 23 were Dalits. This included two in the prestigious All-India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi, and 11 in Hyderabad city alone. Systematic data does not exist for such suicides, but the problem runs far deeper than a few students deciding to end their own lives after being defeated by the system. Dalit dilemma in India reads like an entire data sheet of tragedies. According to a 2010 report by the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) on the Prevention of Atrocities against Scheduled Castes, a crime is committed against a Dalit every 18 minutes. Every day, on average, three Dalit women are raped, two Dalits murdered, and two Dalit houses burnt. According to the NHRC statistics put together by K.B. Saxena, a former additional chief secretary of Bihar, 37 per cent Dalits live below the poverty line, 54 per cent are undernourished, 83 per 1,000 children born in a Dalit household die before their first birthday, 12 per cent before their fifth birthday, and 45 per cent remain illiterate. The data also shows that Dalits are prevented from entering the police station in 28 per cent of Indian villages. Dalit children have been made to sit separately while eating in 39 per cent government schools. Dalits do not get mail delivered to their homes in 24 per cent of villages. And they are denied access to water sources in 48 per cent of our villages because untouchability remains a stark reality even though it was abolished in 1955. We may be a democratic republic, but justice, equality, liberty and fraternity-the four basic tenets promised in the Preamble of our Constitution-are clearly not available to all. Dalits continue to be oppressed and discriminated against in villages, in educational institutions, in the job market, and on the political battlefront, leaving them with little respite in any sphere or at any juncture of their lives.

All this even while there has been no dearth of political rhetoric, or creation of laws, to pronounce that Dalits must not get a raw deal. The Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955, and the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, prescribe punishments from crimes against Dalits that are much more stringent than corresponding offences under the IPC. Special courts have been established in major states for speedy trial of cases registered exclusively under these Acts. In 2006, former prime minister Manmohan Singh even equated the practice of "untouchability" to that of "apartheid" and racial segregation in South Africa. In December 2015, the SC and ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Amendment Bill, passed by Parliament, made several critical changes. New activities were added to the list of offences. Among them were preventing SCs/STs from using common property resources, from entering any places of public worship, and from entering an education or health institution. In case of any violation, the new law said that the courts would presume unless proved otherwise that the accused non-SC/ST person was aware of the caste or tribal identity of the victim. So why have violent incidents against Dalits increased, rather than decreased over the years, in spite of Constitutional protection and legal safeguards? "Caste is not simply a law and order problem but a social problem. Caste violence can only be eradicated with the birth of a new social order," says Chandra Bhan Prasad, co-author of Defying the Odds: The Rise of Dalit Entrepreneurs. He argues that the upward mobility of some Dalits caused by market reforms post-1991, ironically leads to higher incidence of atrocities in the form of a backlash.

Education, the hotbed

Protest is starting to brew in institutions of higher education. At Delhi's Jawaharlal Nehru University, hundreds of students gathered at the Ganga dhaba on the eve of Vemula's 27th birthday on January 29 to organise a candlelight vigil. Organised under the aegis of Joint Action Committee (JAC), the students were led by the Birsa Munda, Phule and Ambedkar Student's Association (BAPSA), a body formed on November 14, 2014. Birsa, Phule and Ambedkar have replaced Marx, Lenin and Mao in JNU as icons of "identity", and "caste" replaces "class" as the main issue. Who are the new student leaders? Sanghapalli Aruna Lohitakshi, a linguistics Ph.D student from Vishakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, is one of the founding members of BAPSA, which is akin to poet Namdeo Dhasal's Dalit Panthers of the 1970s. She speaks of "ghettoisation by upper-caste students," and "Dalit faculty seats being converted into general seats on the pretext that no suitable Dalit candidates were found". Though BAPSA and groups such as the Ambedkar Students' Association spew venom and spit fire, their struggle highlights a form of subversive protest that fights suppression with suicide. To borrow from JNU Professor Gopal Guru, it showcases the "clash between the life of the mind versus the life of the caste". The primary reason for educational institutions emerging as pulpits of protest lies in the fractured social structure in universities, where the elite of the Dalits are competing with general students. Not only are they more aware of Constitutional provisions, they feel they are treated unfairly by university authorities and student bodies such as the ABVP by virtue of their selection in the reserved category. This is what Rohith had articulated in his suicide note, and was seemingly corroborated by the circumstances behind his suspension from the university after a skirmish with the ABVP.

Rampant segregation

In villages and urban slums, however, where segregation is rampant to this day, voices are stifled even before they can be raised. A stark example of this is a dusty little hamlet called Sunpedh-meaning empty trees-in Ballabhgarh, Haryana, barely 40 kilometres from Delhi. The tension is palpable, the stillness stifling, as the centre of the village feels like a fortress with 65 Haryana police personnel posted to prevent inter-caste clashes. No one greets anyone, no one is smiling.

Untouchability is practised widely in Sunpedh. Ask about Ram Prasad, a local grocery shop-owner, and the instant response from a young man on a motorbike is: "Chamaron ke ilake mein jayiye (Go where the Dalits live). The upper-caste areas are separated from the low-lying Dalit quarters with mud puddles all around. The entire hamlet comprises approximately 2,700 bighas of land, of which 2,000 bighas is owned by 300 families of Thakurs. The rest is owned by Dalit communities, including 150 Ravidas families, and smaller numbers of Valmikis, Garerias, and Dhimars. Most of the Dalits survive as daily-wage labourers in the farms of the Thakurs. Here, on the night of October 21, 2015, four members of a Dalit family were set ablaze inside their house: Jitender, his wife Rekha, and their children Vaivhav, 2, and Divya, nly 10 months old. The village erupted in grief and indignation the next day when the bodies of the infants, wrapped in white shrouds, arrived for cremation. Jitender escaped while Rekha suffered serious burn injuries. Their gutted home is officially sealed, guarded by the police. Jitender's mother Santa Devi, his 85-year old grandmother Buddhan Devi, his aunt Kanta (all three are widows) and his married sister Gita, sleep in the open in the severe winter cold since the house is officially sealed. "There seems no flame of justice, no place to live, no one to earn, no money for lawyers, no one to care for us three widows," says Buddhan. "My brother Jitender threatens to commit suicide every day. Suicide, like the Rohith Vemula case, seems like the only option for a Dalit," laments Gita. A majority of the heinous crimes against Dalits, as documented by the NHRC, are perpetrated in villages in which they are treated as second-class citizens. But discrimination isn't a rural problem alone. Joblessness among Dalits runs through the urban landscape as well. According to 2011 Census data, the unemployment rate for SCs between 15 and 59 years of age was 18 per cent, including marginal workers seeking work, as compared to 14 per cent for the general population. Among STs, the unemployment rate was even higher at over 19 per cent.

Violent heartland

Government data suggests that the usual suspect in terms of incidence of crime committed against SCs is the Hindi heartland. Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan top the list with 8,075 and 8,028 cases respectively in 2014. Bihar is the third-worst with 7,893 incidents. Neither the political regime, nor the ideology of the ruling political party, nor the presence of major Dalit parties within the states makes a difference. Rajasthan and MP are ruled by BJP governments, Uttar Pradesh by the SP and Bihar by the JD (U). All the parties are equally guilty of sins of omission and commission. "The absence of social reform movements in the heartland states in contrast to the southern states has contributed to the presence of brutal caste wars in the north," says P.S. Krishnan, a former welfare secretary. In the south, the undivided Andhra Pradesh is the worst performer with 4,114 atrocities recorded in 2014. Part of the reason for this is the backlash by privileged groups against a new form of assertion of rights and display of aspirations by Dalit youth. The emergence of Dalit parties such as Mayawati's BSP, and the rise of Maoists in Bihar and Andhra Pradesh, explains the rise of violent incidents in these states. An assertion of Dalit rights, whether in terms of identity politics (in Uttar Pradesh), or class politics (Bihar and Andhra Pradesh), leads to a backlash. All through the 1990s, Bihar was wracked by caste wars-most notably Ranvir Sena versus Lal Sena-in parts of Jehanabad, Aurangabad, Gaya and Bhojpur. Dalit politics typically takes two forms: militant movements and electoral coalitions. The democratic electoral route is ironically poised on the cusp of a cruel paradox in which Dalit groups must either ally with mainstream political parties and risk compromising with the Dalit agenda; or fight it out alone and risk getting pushed to the margins. It is a Hobson's Choice. The reason is that the spread of Dalit population throughout India is such that by themselves they are always in a minority. In any electoral battle, they can only benefit if they form an alliance either with other dominant caste groups, or mainstream political parties. In Uttar Pradesh, for example, Mayawati allied initially with mainstream parties-Congress, BJP and the Samajwadi Party-but ended up quitting the alliance each time in a huff. Later, she changed her strategy by forming alliances "directly with upper-caste groups and minorities", says BSP's Sudhindra Bhadoria. "The Brahmins and Thakurs form an alliance with BSP not because they have an ideological affinity but because they want to defeat the Yadav-led SP," adds another BSP leader. In spite of such alliances, however, the BSP faced defeats in the 2012 Assembly polls and 2014 Lok Sabha elections in UP because its math was trumped by the Yadav-Muslim combine and the consolidation of the Hindu vote.

The way out

The obvious ways to ensure that the lot of the Dalits is improved are education, rise in economic status, market reforms transforming the lives of millions of Dalits living in impecunious conditions. But not many experts are convinced of this path to empowerment. "Market reforms can touch the life of a few thousands of Dalits but it simply creates an island of prosperity amongst a sea of penury," says Guru, arguing that social movements are the only solution. Krishnan, on the other hand, believes that constitutional safeguards and protective legal clauses can play a great enabling role. But, more than any of this, a change of attitude is needed among the ruling classes to stem the tide. Perhaps the best solution was provided by B.R. Ambedkar in the Constituent Assembly. "We are entering an era of political equality. But economically and socially we remain a deeply unequal society. Unless we resolve this contradiction, inequality will destroy our democracy," he had warned. But nothing learnt; little progress made. The Dalit dilemma, ironically, is the dilemma of India. Some hard questions remain: How long must the discrimination continue? How many dreams must be shattered? How many flames of justice must be extinguished? How many Vaibhavs and Divyas must be burnt alive? How many Rohiths must die to change India, once and for all?

2013-15: State-wise atrocities against Dalits

The Hindu, July 25, 2016

Vikas Pathak,G Sampath

U.P., Bihar lead in crimes against Dalits

Data from Gujarat show such atrocities impossibly make up 163% of the total number of crimes. Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Bihar lead the country in the number of cases registered of crimes against the Scheduled Castes, official data pertaining to 2013, 2014 and 2015 show.

The National Commission for Scheduled Castes (NCSC) counts these States among those deserving special attention.

While U.P. has witnessed a political war of words over an expelled BJP leader's insulting remarks on BSP leader Mayawati, it is Rajasthan that leads in number of crimes against Dalits.