Caste among Hindus

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

History

Rigidification of caste under British colonial rule

Sanjoy Chakravorty, June 19, 2019: BBC

From: Sanjoy Chakravorty, June 19, 2019: BBC

A Google search for basic information on India's caste system lists many sites that, with varying degrees of emphasis, outline three popular tropes on the phenomenon.

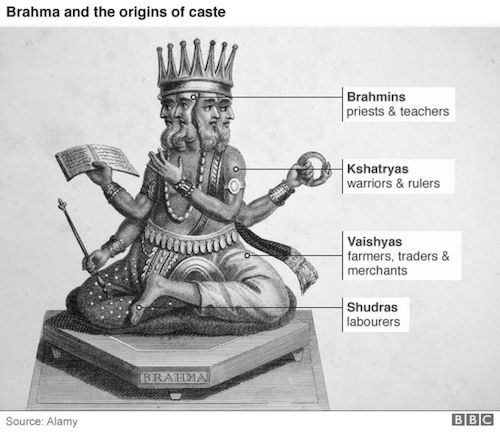

First, the caste system is a four-fold categorical hierarchy of the Hindu religion - with Brahmins (priests/teachers) on top, followed, in order, by Kshatriyas (rulers/warriors), Vaishyas (farmers/traders/merchants), and Shudras (labourers). In addition, there is a fifth group of "Outcastes" (people who do unclean work and are outside the four-fold system).

Second, this system is ordained by Hinduism's sacred texts (notably the supposed source of Hindu law, the Manusmriti), it is thousands of years old, and it governed all key aspects of life, including marriage, occupation and location.

Third, caste-based discrimination is illegal now and there are policies instead for caste-based affirmative action (or positive discrimination). These ideas, even seen in a BBC explainer, represent the conventional wisdom. The problem is that the conventional wisdom has not been updated with critical scholarly findings.

The first two statements may as well have been written 200 years ago, at the beginning of the 19th Century, which is when these "facts" about Indian society were being made up by the British colonial authorities. In a new book, The Truth About Us: The Politics of Information from Manu to Modi, I show how the social categories of religion and caste as they are perceived in modern-day India were developed during the British colonial rule, at a time when information was scarce and the coloniser's power over information was absolute.

This was done initially in the early 19th Century by elevating selected and convenient Brahman-Sanskrit texts like the Manusmriti to canonical status; the supposed origin of caste in the Rig Veda (most ancient religious text) was most likely added retroactively, after it was translated to English decades later.

These categories were institutionalised in the mid to late 19th Century through the census. These were acts of convenience and simplification. The colonisers established the acceptable list of indigenous religions in India - Hinduism, Sikhism, Jainism - and their boundaries and laws through "reading" what they claimed were India's definitive texts.

What is now widely accepted as Hinduism was, in fact, an ideology (or, more accurately, a theory or fantasy) that is better called "Brahmanism", that existed largely in textual (but not real) form and enunciated the interests of a small, Sanskrit-educated social group.

There is little doubt that the religion categories in India could have been defined very differently by reinterpreting those same or other texts.

The so-called four-fold hierarchy was also derived from the same Brahman texts. This system of categorisation was also textual or theoretical; it existed only in scrolls and had no relationship with the reality on the ground.

This became embarrassingly obvious from the first censuses in the late 1860s. The plan then was to fit all of the "Hindu" population into these four categories. But the bewildering variety of responses on caste identity from the population became impossible to fit neatly into colonial or Brahman theory.

WR Cornish, who supervised census operations in the Madras Presidency in 1871, wrote that "… regarding the origin of caste we can place no reliance upon the statements made in the Hindu sacred writings. Whether there was ever a period in which the Hindus were composed of four classes is exceedingly doubtful”.

Similarly, CF Magrath, leader and author of a monograph on the 1871 Bihar census, wrote, "that the now meaningless division into the four castes alleged to have been made by Manu should be put aside". Anthropologist Susan Bayly writes that "until well into the colonial period, much of the subcontinent was still populated by people for whom the formal distinctions of caste were of only limited importance, even in parts of the so-called Hindu heartland… The institutions and beliefs which are now often described as the elements of traditional caste were only just taking shape as recently as the early 18th Century”.

In fact, it is doubtful that caste had much significance or virulence in society before the British made it India's defining social feature.

Astonishing diversity

The pre-colonial written record in royal court documents and traveller accounts studied by professional historians and philologists like Nicholas Dirks, GS Ghurye, Richard Eaton, David Shulman and Cynthia Talbot show little or no mention of caste.

Social identities were constantly malleable. "Slaves" and "menials" and "merchants" became kings; farmers became soldiers, and soldiers became farmers; one's social identity could be changed as easily as moving from one village to another; there is little evidence of systematic and widespread caste oppression or mass conversion to Islam as a result of it.

All the available evidence calls for a fundamental re-imagination of social identity in pre-colonial India.

The picture that one should see is of astonishing diversity. What the colonisers did through their reading of the "sacred" texts and the institution of the census was to try to frame all of that diversity through alien categorical systems of religion, race, caste and tribe. The census was used to simplify - categorise and define - what was barely understood by the colonisers using a convenient ideology and absurd (and shifting) methodology.

The colonisers invented or constructed Indian social identities using categories of convenience during a period that covered roughly the 19th Century.

This was done to serve the British Indian government's own interests - primarily to create a single society with a common law that could be easily governed.

A very large, complex and regionally diverse system of faiths and social identities was simplified to a degree that probably has no parallel in world history, entirely new categories and hierarchies were created, incompatible or mismatched parts were stuffed together, new boundaries were created, and flexible boundaries hardened.

The resulting categorical system became rigid during the next century and quarter, as the made-up categories came to be associated with real rights. Religion-based electorates in British India and caste-based reservations in independent India made amorphous categories concrete. There came to be real and material consequences of belonging to one category (like Jain or Scheduled Caste) instead of another. Categorisation, as it turned out in India, was destiny. The vast scholarship of the last few decades allows us to make a strong case that the British colonisers wrote the first and defining draft of Indian history.

So deeply inscribed is this draft in the public imagination that it is now accepted as the truth. It is imperative that we begin to question these imagined truths.

Sanjoy Chakravorty is professor in the College of Liberal Arts at Temple University, Philadelphia

Caste discrimination

Discrimination is recent

The Times of India Feb 02 2016

Amish

Ancient India did not sanctify it, caste discrimination is more recent than we think

The tragic death of Rohith Vemula has again brought to the forefront of public imagination the painful reality of caste discrimination in Indian society . Notwithstanding the noise generated by relentless pursuit of politics, evidence clearly indicates that the Scheduled Castes as a group do face terrible prejudice in India.

Understandably, many non-Westernised Indians would be loathe to accept the `atrocity literature' churned out by Western academics NGOs. After all, among the most oppressed minorities in the civilised world are the AfricanAmericans and the European Romas, as evidenced by various detailed studies.

However, the hypocrisy of Western academics media NGOs cannot be an excuse for Indians not to confront their own failings. The present birth-based caste system and caste system and its attendant societal discrimination is a blot on India and completely against the conceptualisation of our ancient culture.

There are some who claim that the present caste system is sanctified by our ancient scriptures. Not true. B R Ambedkar, in his scholarly book `Who were the Shudras?', had used Indian scriptures and texts to prove that in ancient times India had widely respected Shudra rulers as well, and the oppressive scriptural verses, justifying discrimination and a caste system based on birth, were interpolated into the texts later.

In the Bhagwad Gita, Lord Krishna clearly enunciates that He created the four varnas based on guna (attributes) and karma; birth is NOT mentioned.Rishis, or sages, were accorded the highest status in ancient India, and two of our greatest epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, were composed by Rishis who were not born Brahmins.

Valmiki was born a Shudra and Krishna Dwaipayana (also known as Ved Vyas) was born to a fisherwoman. Satyakam Jabali, believed to have composed the celebrated Jabali Upanishad, was born to an unwed Shudra mother and his father's name was unknown. According to the Valmiki Ramayana, Jabali was an officiating priest and adviser to the Ayodhya royalty during Lord Ram's period.

Arvind Sharma, professor of comparative religion at McGill University, states that caste rigidity and discrimination emerged in the Smriti period (from after the birth of Jesus Christ and extending up to 1200 CE) and was challenged in the medieval period by the bhakti movement led by many non-upper caste saints. At the time even powerful empires emerged that were led by Shudra rulers, for example the Kakatiyas. Then, the birth-based caste system became rigid once again around the British colonial period. It has remained so, ever since.

Scientific evidence provided by genetic research corroborates the ancient scriptural absence of a birth-based caste system. Banning of inter-marriage in pursuance of `caste purity' is a fundamental marker of this birth-based caste system.Various scientific papers published in journals such as the American Journal of Human Genetics, Nature and the National Academy of Sciences Journal, have established that inter-breeding among different genetic groups in India was extremely common for thousands of years until it stopped around 0 CE to 400 CE (intriguingly, this is in sync with the period when Sharma says caste discrimination arose for the first time in recorded history).

The inference is obvious. The present birth-based caste system a distorted merger of jati (one's birth-community) and varna (one's nature based on guna and karma) emerged roughly between 1,600 to 2,000 years ago. It did not exist earlier. Note that the word `caste' itself is a Portuguese creation, derived from the Portuguese Spanish `casta' meaning breed or race.

The founding fathers of the Indian republic were, thankfully , aware of the pernicious effects of the birth-based caste system on Indian society . The Indian Constitution had bold objectives. But, as is obvious today , while government policies such as reservations have made a difference, they have not been good enough.

The work of Dalit scholar Chandra Bhan Prasad shows that the post-1991 economic reforms programme has seminally addressed this issue. According to the 200607 All-India MSME Census, approximately 14% of the total enterprises in the country are owned by SCST entrepreneurs, and they generate nearly 8 million jobs! The figure is probably much higher today .

There are many who claim that the reservations policy has ignored the upper caste poor and rural landless. This may hold some truth. But this is also largely due to the absence of enough education facilities and jobs, which leads to rationing of the few opportunities that do exist.

Post-1991 reforms have no doubt brought down these shortfalls, but they have not gone far enough. Many argue that reformist policies will not just help the Dalits, but also the rural and urban upper-caste poor.

So, as Prasad has pointed out repeatedly, more economic reforms and urbanisation will go much further in mitigating caste discrimination and poverty in general, compared to government policies. However, caste discrimination must be opposed and fought against by all Indians, for the sake of the soul of our nation.

Annihilating the birth-based caste system is a battle we must all engage in at a societal level. We will honour our ancient culture with this fight. More importantly , we will end something that is just plain wrong.

Rejecting caste

Kerala, 2018: Many students do not state caste, religion in classes 1-X; in classes XI-XII most do

‘Caste away’ for 1.2L students in Kerala, March 29, 2018: The Times of India

Over 1.23 lakh students did not disclose their caste or religion while being admitted to various classes — ranging from I and X — in government and govt-aided schools across Kerala in the 2017-18 academic session.

Education minister C Raveendranath, who disclosed this in the assembly on Wednesday, said the number of students who left the column related to caste and religion blank this year was a record high. These students belonged to 9,209 government and aided schools in the state.

A consolidated figure could be arrived at this year as details of admissions were recorded through Sampoorna software instead of manually tabulating it in all education districts.

However, director of public instruction K V Mohankumar injected a cautionary note regarding this data, saying that it doesn’t reflect a “progressive” mindset. “Based on court orders, it is no longer mandatory for students to mention their caste or religion. As a result, schools cannot compel anyone to mention their caste now. Hence these students may have chosen not to mention it,’’ he said.

Ajay Kumar, executive director of Rights, an NGO working for uplift of Dalits, also voiced certain reservations on what the data implied. “It has been only 60 years since Dalits in Kerala have accessed education. Even today, they are not in a position to sacrifice their legitimate rights”, he said. In higher secondary classes the number nose-dived with just 517 students chose not to reveal their caste or religion.

See also

Caste in India: genetics and heredity (easy reading)

Caste among Hindus