Caste-based reservations, India (history)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

History

1831 – 1990: a brief history

The idea of quotas, reservation, or preferential treatment for the socially disadvantaged, is very old in India. It is frequently believed that the US pioneered affirmative action in the 1960s; in fact, India had recognised social disadvantage much earlier.

The recognition of ‘backwardness’ as a social condition of discrimination — something that sometimes can’t be transcended even through upward class mobility — is important. And efforts to provide for representation to “non-Brahmin” castes predates the Mandal report; in some cases, even India’s independence.

While broader rules on Indiawide class/caste reservations in jobs can be said to have been framed in 1993, when the Supreme Court heard petitions against the implementation of the Second Backward Castes (or “Mandal”) Commission, the experience of states, especially in southern and western India, dates to the 1800s, and involves social movements, princely states and the Raj.

Tamil Nadu, with its history and context of caste movements, is special, and has had reservation since 1831 — when, under pressure, the Raj initiated the idea of quotas. The social justice movement against the repression of non-Brahmin castes peaked between 1910 and 1920 and, by 1921, reservation for BCs (backward castes), SCs and STs was initiated. In the 1930s, pressure for reserving more for the BCs increased, and governments responded. By 1990, there was 30% reservation for BCs, 20% for MBCs, and 18% and 1% for SCs and STs respectively.

Around the same time, the Mysore state and princely states of Travancore and Kochi took note of popular support for the idea of reserving places in education, and the pressure from the backward communities and Dalits ensured they acted on it.

In 1919, the king of Mysore formed a committee headed by a judge to study the feasibility of reservations, and a plan was under way. In Kerala too, reservation for Ezhavas, Muslims, Other Backward Hindus, Latin Catholic and Anglo-Indians, and backward Christians were in effect for years before independence.

The state of Kolhapur introduced reservations in 1902 — for backward castes in education.

Ideas about reservation in independent India were shaped significantly by the so-called Poona Pact between B R Ambedkar and Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi had vehemently opposed as divisive the communal award of August 1932, which separated Dalits (then called the “untouchables”) from Hindus, while Ambedkar was for it.

Gandhi went on a fast in jail, but eventually, though initially reluctantly, agreed to a compromise with Ambedkar in September 1932, under which a higher number of seats was promised for Dalits under the Hindu umbrella.

The Constituent Assembly for independent India’s Constitution carried forward the commitment to reservations for Scheduled Castes and Tribes as part of this promise — and quotas for SCs and STs is, therefore, the only explicit reservation that was written in.

According to some scholars, when some SC members of the Drafting Committee, apprehensive about the stance Sardar Patel (who was known to oppose reservations) might adopt, approached Ambedkar, he asked them to speak to Gandhi — and to remind the Mahatma of the commitment to Hindus at the bottom of the heap. And that is what ensured SC/ST reservations found a place in the Constitution.

Later, a debate ensued on this, as a Government Order in 1950 excluded converts (except four Sikh Dalit caste groups) from this reservation.

Slowly, by the 1990s, Sikh and Buddhist castes were included, but Christian and Muslim Dalits remain excluded.

Among North Indian states, Bihar adopted reservation for backward castes in 1978, when the socialist leader Karpoori Thakur was at the helm. He implemented the report of the Mungeri Lal panel, which was set up in 1971. Like Mandal, which came in later, this report said backward castes irrespective of faith needed reservation.

The Mandal Commission presented its report in 1980, but was dusted up by the National Front Prime Minister V P Singh for implementation in 1990.

The rest, as they say, is history.

1921-1994: Tamil Nadu

K Subramanian, August 24, 2021: The Times of India

From: K Subramanian, August 24, 2021: The Times of India

At a time when Maharashtra, Karnataka, Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh are struggling to fix the reservation quota beyond 50%, only Tamil Nadu has managed to have 69%. Decades of struggle and timely state intervention ensured that TN was ahead of others.

The original communal government order (GO) passed by the provincial government led by the Justice Party in the Madras Presidency was designed to check the near monopoly of brahmins in government jobs and seats in public higher education institutions. (On the ground that brahmins constituted only about 3% of the population while the backward communities constituted 89%).

It all began with the Justice Party government of Raja of Panagal, which introduced caste based reservation in 1921. The first communal GO was passed by the Madras Presidency government. It provided for reservation of 44% jobs for non-brahmins, 16% for brahmins, 16% for Muslims, 16% for Anglo-Indian and Christians and 8% for scheduled castes. Since then the reservation policy had been in operation in Tamil Nadu. These opportunities in government were to be shared among non-brahmins, brahmins, Hindus, Muhammadans, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians, Europeans and others.

After Independence, in Tamil Nadu, the first backward class commission headed by A M Sattanathan, submitted its report in 1970. Based on its recommendations the backward class (BC) reservation was enhanced to 31% from 25% and SC/ST to 18 % from 16 % and this took the state’s total reservation to 49%. Again pursuant to the order passed by the Supreme Court dated October 15, 1992, the second backward class commission was appointed. The commission’s report led to the reservation for BCs being raised to 50%, taking TN’s total reservation to 68%. Based on a Madras high court judgment in 1990, the state fixed 1% quota for scheduled tribes and this took TN’s overall reservation to 69%. The Supreme Court of India in the case reported State of Madras vs Champakam Dorairajan (1951) rejected the contention based on the communal government order dated June 16, 1950, which laid down the rules for selection of candidates for admission into the medical colleges and held that the classification made in the communal GO is opposed to the Constitution. To override the decision of the Supreme Court, Clause 4 was introduced in Article 15 of the Constitution with the aim of making it constitutional for the state to reserve seats for BCs, Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST) in educational institutions as well as to make other special provisions as may be necessary for their advancement.

Article 31 (B) was inserted as well by way of abundant caution to save the particular act in the Ninth Schedule to the Constitution, notwithstanding any decision of a court/tribunal that any of those Acts is void for contravention of any fundamental right. The objective and principles upon which the Ninth schedule was initially introduced was primarily on land reforms and agrarian reforms and land acquisition to abolish the zamindari system and bring about social reforms. Since the land reform legislation impinged upon the fundamental right to property of landlords, this proved to be the biggest obstacle in implementing reforms. To remove such an obstacle, Article 31(B) read with Ninth Schedule was incorporated under the provisions of the Constitution through the First Amendment Act, 1951.

In 1992, judgment of a nine judge bench of the Supreme Court in what is known as the Mandal case (Indra Sahani vs Union of India) held that total reservation under Article 16 (4) should not exceed 50%. Shortly after this judgment the Tamil Nadu government moved the Madras high court for continuing its present reservation policy as hitherto followed during the academic year 1993-94. The court ruled that the reservation policy could continue, but the quantum of reservation should be brought down to 50% during the next academic year i.e. 1994-95. In the special leave petition by the state, the Supreme Court passed an interim order reiterating that the reservation should not exceed 50% in the matter of admission to educational institutions.

Major legal problems erupted pursuant to the order passed by the Supreme Court that the state government cannot breach the 50% cap on reservation. By this time various political parties and social forums representing BCs requested the state to consider all the ramifications of the Supreme Court order.

Since the state did not get any reprieve, CM J Jayalalithaa began looking for alternate legal recourse. Since the policy needed a strong legislative support, it was clear that apart from bringing legislation in the state assembly, the bill needed Presidential assent for notifying the law under the proviso to Article 31(A), and thereafter the said law must be included in the Ninth Schedule. Article 31(B) of the Constitution was incorporated under the provisions of the Constitution through the first amendment Act 1951 and once the proposed Tamil Nadu Act is included in the Ninth Schedule it could not be challenged. In a special session of the Tamil Nadu assembly held in 1993, it was unanimously resolved calling upon the Union government to take steps immediately to bring in suitable amendments to the Constitution so as to enable the state to continue its policy of 69% reservation. The bill passed by the Tamil Nadu assembly came into effect after President Shankar Dayal Sharma gave his assent to the bill and the TN Act was notified as Act 45 of 1994.

Thereafter on July 22, 1994, the state requested the Union government that the law be included in the Ninth Schedule of the Constitution. There have been pleas that have been filed in the Supreme Court against the inclusion of the Tamil Nadu Act in the Ninth schedule on the ground that it is unconstitutional and against Article 14. The continuance of 69% reservation would depend upon the outcome of the pending cases.

Tamil Nadu vs Centre: A three decade fight for OBC reservation

September 16, 1921: The Justice Party in government passed the first Communal Government Order, becoming the first elected body in India to legislate reservations

1946: Quota for SCs increased from 8.33% to 12.33%

1951: OBC reservation of 25%, along with 16% for SC/ST introduced

1971: OBC quota increased to 31% and SC/ST quota to 18%

1980: M G Ramachandran introduced ‘creamy layer’ and income ceiling for quota benefits. After protests, he withdrew it, and increased OBC quota to 50%, taking reservation percentage to 68%

1989: Due to Vanniar Sangam protests, M Karunanidhi government split the 50% OBC quota and granted 20% for most backward communities (MBC). An 1% exclusive quota for STs was added, taking total reservation percentage to 69%

1992-1994: Though SC kept 50% ceiling for reservations in the Mandal judgment in 1992, the Jayalalithaa government insulated it from judicial review. Several rounds of litigations ensued, and batches of cases are still pending before SC

The writer is a former advocate general of Tamil Nadu who was instrumental in including the state enactment in the Ninth Schedule of the Constitution

Breaching the 50% upper limit

Arun Janardhanan, May 7, 2023: The Indian Express

Breaching the 50% upper limit set for reservation by the Supreme Court is no easy task, as other states which recently increased their quotas for particular groups only to have had their legislation stuck at different levels have seen.

However, while upholding the Centre’s 10% reservation for Economically Weaker Sections in November 2022, the Supreme Court opened a window by suggesting that the 50% ceiling was not inflexible.

Some states, such as Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand which have tried to raise their quota ceilings have sought that their Bills seeking the same be put under the Ninth Schedule of the Constitution, which would put them in a “safe harbour” when it comes to judicial review. Most of the laws protected under the Schedule concern agriculture / land issues.

In Karnataka itself, the Congress manifesto came days after the Supreme Court stayed the incumbent state BJP government’s pre-poll order of scrapping the 4% reservation for Muslims and distributing it equally among the state’s two dominant communities, Lingayats and Vokkaligas.

Earlier, in 2021, the Supreme Court had struck down the Maharashtra government’s provision of providing a Maratha quota, for exceeding the 50% ceiling limit.

The Tamil Nadu 69% quota came on the back of its long history of social justice. Currently, it comprises 18% for SCs, 1% for STs, 20% for Most Backward Classes (MBCs), and 30% for Backward Classes (BCs), which also include Christians and Muslims.

In the days after Independence, Tamil Nadu had 16% reservation for SCs and STs, as Constitutionally mandated, apart from 25% for backward classes.

In 1971, the M Karunanidhi-led DMK government increased OBC reservation to 30% and that for SC/STs to 18%, with 1% set aside for STs. In 1989-90, again when Karunanidhi was the CM, the DMK government set aside 20% reservation exclusively for MBCs, taking them out of OBCs, who continued to retain 30% overall now as BCs, for state government educational institutions and jobs.

Karunanidhi decided to split the MBCs and BCs after an agitation by PMK founder S Ramadoss in the late 1980s. Since the 1970s, there had been panels that validated this, including the A N Sattanathan Commission (1971) and J A Ambasankar Commission (1982) under the MGR regime.

When the Tamil Nadu quota ran into legal obstacles after the Supreme Court’s 1992 verdict setting a 50% ceiling, the then CM J Jayalalithaa, along with other leaders of various parties, led a delegation to New Delhi to meet then Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao. Tamil Nadu’s reservation provision was then included in the Ninth Schedule.

However, the debate on reservation is far from settled even in Tamil Nadu. Literally minutes before the Election Commission announced the schedule for the Assembly elections in Tamil Nadu in 2021, the then AIADMK regime had declared an additional 10.5% reservation for OBC Vanniyars.

The announcement, not surprisingly, stirred a hornet’s nest. The Vanniyars are represented by the Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK), an ally of the AIADMK and NDA, and other OBC castes such as Thevars and Gounders immediately protested against the move to give the Vanniyars the quota privilege.

Then CM Edappadi K Palaniswami, a Gounder, and Deputy CM O Panneerselvam, a Thevar, both faced backlash from their own vote banks. Panneerselvam, who made his displeasure at Palaniswami’s decision known, was compelled to promise voters that the quota to Vanniyars was “temporary” and would last only till a caste-wise census was done and, presumably, settle the questions of backwardness as well as strength of various groups.

Incidentally, in 2021, the AIADMK government had set up a commission to collect quantifiable data on castes, communities, and tribes, and to work out the methodology for conducting a caste survey, appointing retired Madras High Court judge Justice A Kulasekharan, as chairman. The panel is yet to complete its work.

In any case, the AIADMK lost the 2021 elections and went out of power, while the Vanniyar reservation move didn’t survive the Madras High Court. In November 2021, the court quashed the decision as “ultra vires of the Indian Constitution”.

Cut to 2023, and the approaching Lok Sabha elections. It’s the DMK that is in power now, and Chief Minister M K Stalin is one of the leading Opposition voices seeking that the Modi-led government at the Centre hold a caste census.

In a recent policy note, the DMK government stressed that it was committed to implementing and protecting the 69% quota in educational institutions and appointments in government service.

Political observers say it is not surprising that different governments have found it simpler to kick the can down the road, rather than base their caste arguments on concrete data. Retired HC judge Justice K Chandru says the process is complex and certain to lead to protests, from communities left out as well as those expecting a higher share, making inflated claims of their numbers.

On the Congress’s 75% quota promise, Justice Chandru says: “75% is not illegal, but to arrive there, you need a caste census, discounting earlier numbers.

Karnataka’s case is further complicated by the presence there of a powerful mutt culture and two dominant castes, Lingayats and Vokkaligas. Tamil Nadu’s political landscape is comparatively less complex.

1921: Mysore

Narendar Pani, Oct 5, 2023: The Times of India

The debate has shifted from the approach of keeping out the forward castes to one of seeking representation for all castes; from the aggressive backward-versus-forward caste rhetoric of Mandal to a more inclusive approach reminiscent of the first reservations in India – in Mysore in 1921.The social strife generated by the acceptance of the Mandal report was, in part, due to its disconnect with the way caste works in India. Its emphasis on mobilising the backward castes against the forward castes was based on the view that caste was no more than a proxy for class. But as sociologists have pointed out, social and economic exclusion was only true for Scheduled Castes. Castes just below the line drawn between backward and forward castes were not all that much worse off than castes just above that demarcation.The initial response of castes above the demarcation was to turn against reservations. But they soon realised they would be better off claiming reservations themselves. This resulted in a variety of castes known for their dominance claiming reservations, from Patidars of Gujarat to Lingayats in Karnataka. As dominant castes began to claim reservations there weren’t too many forward castes to campaign against reservations. The focus shifted from debating the necessity of reservations to the share of reservations each caste should get.In keeping with the tendency of the debate on reservations to move quickly to extreme positions, the case now being put forward is that each caste should have a share in seats and jobs on par with its share of the population. Even as this approach makes the much-needed case for representativeness, it is not without its problems.When taken to its logical conclusion, the only way of ensuring that the share of seats and jobs of all castes is the same as their share of the population, would be to reserve all seats and jobs. That would be to do away with any limit on reservations. And it will not meet the needs of social justice either, because both the most dominant castes as well as the worst-off castes would be treated on par. Each would only get seats and jobs on par with their share of the population.If the polity is inclined to step back from politically expedient positions to develop a system that allows for merit and representation, there are inputs available from historical experiments with reservations. The reservations of 1921 in the princely state of Mysore sought to merge objectives of free competition with that of social representation. It did so by reserving 50% of jobs in government so that the other half of the jobs was left to open competition.The interests of representation were then met by ensuring virtually all castes, except for the few that overwhelmingly dominated the bureaucracy, were entitled to a place in the reserved category. It addressed the needs of social justice by ensuring that those at the bottom of the caste hierarchy received a share of the reserved jobs that was greater than their share of the population, while those closer to the top of the hierarchy had a share of reserved jobs that was less than their share of the population.The greatest advantage of the Mysore reservations was that it did not result in the kind of inter-caste hostility the Mandal report generated. With very few excluded from reservations the battles were those of individual castes seeking a greater share rather than an all-out war between those who benefitted and those who were left out. It also allowed for continued monitoring of the social justice aspect of reservations.The socio-economic status of castes could be evaluated at different points to determine whether a caste remained backward and hence required a share greater than its share of the population, or whether its status had improved to a point where it could do with a share less than its share of the population.Having the country go back to the Mysore reservations would require answers to two questions. First, what should be the distribution of seats and jobs between open competition and reservation? It is doubtful if the limit of 50% can withstand the sustained assault from a multitude of political parties. But it is important not to dramatically reduce the share of seats left to open competition. The ‘General’ quota does offer some space for the best from any caste or community. It may be dominated by a few castes today, but it would be wrong to believe that others will never be good enough to compete in this category.Second, what should be the share of reserved seats and jobs for each caste or other identity group? Ideally, the share for the worst-off would need to be greater than their share of the population. But if the caste survey tells us, as it has in Bihar, that the share of the worst-off castes is much less than their actual share of the population, even getting their share on par with their share of the population would be a major step forward. The writer is dean of social sciences at National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru

After 1947: Evolution of the terms SC, ST, OBC

Quotas born with Brits, took on life of their own after 1947, April 9, 2018: The Times of India

Dalit fury brought the country to a standstill on April 2 as the members of the community took to the streets against a Supreme Court order on the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. Amid protests, the Centre filed an appeal against the SC order and also assured the community that caste-based quotas will continue. A look at how these quotas came into being in the first place and why they are such a sensitive matter…

How was the term ‘Scheduled Tribe’ born?

• Most of the tribal population was not included among depressed classes. According to the historian Ramachandra Guha, the first report on minority rights made public in August 1947 provided for reservations for untouchables only. Jaipal Singh Munda, who was representing the tribal community in the constituent assembly, called for reservation for tribals too. The proper task of scheduling tribes and making an inclusive schedule for deprived classes happened in 1950 when the Constitution of India came into force, providing also for reservation in government service and education to redress the historical under-representation of these sections in these institutions.

How did the concept of Scheduled Castes evolve?

• During colonial rule, the British classified historically disadvantaged sections in India’s rigid caste hierarchy as depressed classes. In the August 4, 1932, Communal Awards, they extended their proposal of separate electorates for Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, etc. to the depressed classes as well. But Indian leaders saw it as part of the British ploy of divide and rule. Mahatma Gandhi staged a fast, broken after B R Ambedkar agreed to the Poona Pact, whereupon it was accepted that instead of separate electorates, there will be reserved constituencies for the depressed classes. The first listing (scheduling) of these castes was started in preparation for the 1937 elections.

What are Other Backward Classes?

• The Constitution had a provision to allow, in the future, reservations for other backward classes. Thus, the Second Backward Classes Commission (Mandal Commission) was constituted and it submitted its report in 1980, recommending reservation for persons from socially and economically backward classes (also known as other backward classes), which came into force on August 13, 1990.

What is the population of OBCs?

• India saw its last caste census in 1931, after which it was discontinued and, hence, unlike for SCs and STs, there is no census data for OBCs. The Mandal Commission estimated that OBCs constituted about 52% of the population. The National Sample Survey Organisation’s 2004-05 survey had put their share at 41%. The Socio-Economic Caste Census (2011) was supposed to ascertain the caste-wise population. But its final report is awaited.

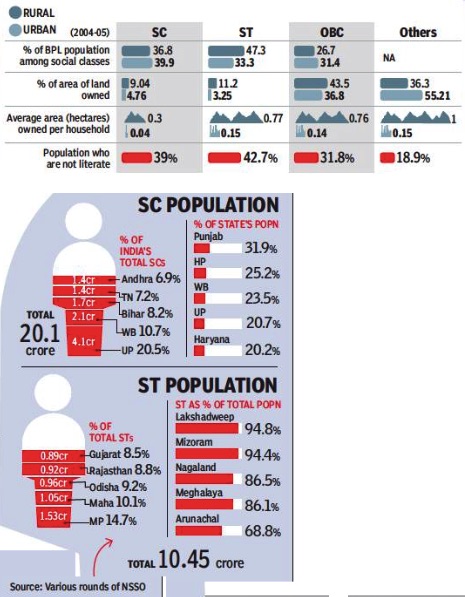

What do social and economic indicators tell us about the various social groups?

• The indicators do point to the deprivation among SC, ST and OBC communities. For instance, a higher proportion of these groups is below the poverty line and illiterate. While OBCs (primarily agricultural communities) have the largest share of land ownership among social groups, the average area owned per household in their case is lower than that for the ‘general’ class.

Which state has the highest SC population?

• In terms of absolute population, about one-fifth of the country’s SC population lives in UP, followed by West Bengal and Bihar. Punjab, however, has the highest proportion of SCs.

Which states have the highest ST population?

• In terms of total population, MP has the highest ST population. However, STs form 94.8% of Lakshadweep’s population, the highest share in any state.

States with high SC, ST populations

The economic status of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes, including literacy, landowning and poverty.

From: Quotas born with Brits, took on life of their own after 1947, April 9, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic, 'States with a high population of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes

The economic status of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes, including literacy, landowning and poverty.'

The evolution of OBC reservations

Dipankar Gupta, How To Subdivide OBCs, September 8, 2018: The Times of India

Government is backing away from social backwardness and moving towards economic criteria

Economic considerations were, on principle, never factored in when reckoning who deserved caste based reservations. It was important to our lawmakers that this policy not be confused with anti-poverty programmes which operate separately, and under different guidelines.

The primary purpose of reservations was to confer dignity to those who were suppressed for centuries and to combat popular discrimination. True, economic uplift would come, as a consequence, but that still did not make it its primary goal.

Now it appears that considerations of economic status might well take centre stage as the government is considering further sub-categories within the Other Backward Classes (OBCs). In the beginning (that is, with the Mandal recommendations), true to the existing rationale of reservations, economic considerations and education (a strong indicator of economic status) were undermined when determining which communities should be classified as OBC.

But because there was no clear marker here as “untouchability” was with SC reservations, the matter ran into some difficulties. This is why it required several test drives before the government finally settled on the Mandal recommendations. Once again, in keeping with the past, as income and wealth were not to be entertained, there was a search for other features that might indicate “social backwardness”.

This led Mandal to favour criteria such as whether manual labour was the source of income, or whether women of the household were in the workforce, or whether the law on age of marriage was observed, to signal “social backwardness”. As features such as these could hardly exclude a majority of people in this country, particularly in villages, the OBC category became all too inclusive.

In the beginning it did not matter so much for it took a while for information of this measure to seep down OBC ranks. For over a decade only the prosperous sections of the rural population, such as Yadavs, Patels and Sonars of Uttar Pradesh (UP), took advantage of Mandal, as their wheel squeaked the loudest and they knew how to amplify that noise.

In the fullness of time other OBC communities, such as the Mauryas, Lodhs and Rajbhars of UP, became aware of Mandal’s formula and wanted to make use of it too. Yet, as the more advanced OBCs stood in their way, they now began to demand a separate quota for themselves.

If truth be told this distinction amongst OBCs was primarily economic, but that could not be openly expressed. Therefore, without much ado or attempts at justification, by government decree and initiated by cabinet decisions, nine states such as Bihar, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana quietly announced further categories within the OBC population.

As a result of this executive action castes such as the Karmakar, the Kanu and the Lohara in Bihar, for example, found a special place for themselves in the newly crafted category called “extremely backward castes”. However, as the agitation for further sub-categorisation has now gone national, the Centre must act.

Unlike what the nine states did on this issue, the NDA government in Delhi has openly declared a search for a clear set of objective criteria on the basis of which further OBC sub-categorisation could take place countrywide. Accordingly, under the stewardship of retired Justice G Rohini a five-member commission has been formed. This move has multiparty support for it was first mooted in 2011 by the UPA government.

This commission was asked “to work out the mechanism, criteria, norms and parameters in a scientific approach for sub-categorisation within such Other Backward Castes …” The commission’s term has recently been extended and its report should be out soon.

However, it appears that the Sachar Committee report and the observations of Justice Pasayat and Justice Panta might impact how the further subcategorisation of OBCs takes place.

While designating Muslims as being a disadvantaged population, Justice Sachar concentrated primarily on the economic and educational status of this community.

Likewise, Justice Pasayat and Justice Panta also asked whether or not inclusion of economic and educational criteria could help in clarifying which communities could be legitimately designated as OBC.

In the meantime, the 27% limit set by the Supreme Court for OBC reservation remains. But as the number of OBCs is much larger, 52% according to Mandal and 41% according to the National Sample Survey, there is widespread dissatisfaction. Quite clearly, the policy, as it stands, is too tightly stitched for comfort. Till the 27% bar is relaxed, it will be OBC versus OBC most of the time. To a large extent, this has diffused the tensions between OBCs and forward castes and increased those within the OBC fold.

If the Maurya, Lohar, Kanu and Lodh castes share the same features of social backwardness with the prosperous Yadavs, the only way to make clear distinctions between them would be on the basis of the economic criterion; the one feature that has so far been taboo in all reservations considerations.

1953, Kalelkar; 1990 Mandal: and after

Express News Service |Mandal Commission report, 25 years later |September 1, 2015| Indian Express

On August 7, 1990, V P Singh tabled the Mandal Commission report in Parliament, setting off an upheaval that pushed a new generation of ‘backwards’ into the forefront of Indian society. Profiles four faces from that defining period.

BACKGROUND

On January 1, 1979, the Morarji Desai government chose Bindeshwari Prasad Mandal, a former chief minister of Bihar, to head the Second Backward Class Commission. Mandal submitted his report two years later, on December 31, 1980. By then, the Morarji Desai government had fallen and Indira Gandhi came to power. It remained in deep freeze during her term and that of Rajiv Gandhi.

THE REPORT

On August 7, 1990, then PM V P Singh announced in Parliament that his government had accepted the Mandal Commission report, which recommended 27% reservation for OBC candidates at all levels of its services. With the implementation of the report, OBC or Other Backward Classes made its way into the lexicon of India’s social justice movement.

THE OPPOSITION

Delhi, September 19, 1990:

Soon after, scattered protests against the OBC quota began in Delhi. In September, Rajeev Goswami, a Delhi University student, set himself on fire, sustaining 50 per cent burns. He survived the immolation bid, but the spark had been ignited. In cities and towns near Delhi, a number of youths set themselves on fire. The south, which had had a long history of political movements for the rights of backward communities, was untouched by the agitation. By then, VP Singh’s government was in serious trouble, but he stood his ground.

The BJP, which supported the government from outside, attempted to shift the political debate from Mandal to the Ram temple and L K Advani set off on his rath yatra. The BJP withdrew support soon after and the V P Singh government fell.

NOT THE FIRST REPORT

In January 1953, the government had set up the First Backward Class Commission under the chairman of social reformer Kaka Kalelkar. The commission submitted its report in March 1955, listing 2,399 backward castes or communities, with 837 of them classified as ‘most backwards’. The report was never implemented.

The Mandal family

Sitting in his Patna house, with a portrait of his father looking over him, Manindra Kumar Mandal flips through an album and pulls out a 1980 photograph of his father presenting the Mandal report to then president Giani Zail Singh. He recalls his father’s “hectic schedule” as he travelled extensively across the country for the report. “My father would tell us how he came across several Rajput families in some states and put them in the OBC category because of their poor socio-economic condition. There is not a single anti-upper caste term in the report,” says Manindra, adding that the report has been maligned by some as being anti-merit and anti-upper castes.

The Mandals were a landed family in Darbhanga but as a child, Manindra says, his father faced social discrimination because they were Yadavs (an OBC caste in Bihar). “While in school, my father would support his less fortunate friends by giving them blankets and coats. But his Brahmin school principal would not allow him to eat with his upper-caste hostel-mates. One day, my father broke down before the principal but he only said it was not such a big deal. My father’s experience made him just the right person to draft this report,” says Manindra, the third of Mandal’s five sons.

He says he doesn’t think of former prime minister Indira Gandhi as an ‘autocrat’. “To me, she was a democrat. The commission was set up by the Morarji Desai government and she could have easily scrapped it after coming to power in 1980 but she allowed two extensions of three months each,” says Manindra, adding that Indira Gandhi had told his father to look into the economic status of classes, besides their socio-educational status.

Mandal died in April 1982, eight years before the report could be accepted. Manindra is bitter about how politicians rode the Mandal wave — with leaders such as Lalu and Nitish coming into their own as Mandal politicians — but how it “hardly benefited me and my brothers”. Manindra was denied a JD(U) ticket in the 2010 Assembly polls.

“The Mandal Commission talks of OBCs as a whole but Bihar followed Karpoori Thakur’s formula and carved out another Extremely Backward Classes (EBC) category. Both Lalu and Nitish dared not implement the commission report because they feared an EBC backlash,” he says.

Reported by Santosh Singh

Signing on the Mandal notification

P S Krishnan: As secretary, welfare ministry, signed on the Mandal notification

‘Debate brought to fore the unnamed’

The summer of 1990 was an eventful one for P S Krishnan, an Andhra Pradesh-cadre IAS officer. He was to retire in a few months as secretary, ministry of welfare, at the Centre, but before that, he had to sign on the August 7 Mandal notification that proposed, among other things, 27 per cent reservation for OBC candidates in central government jobs.

Sitting in his apartment in Gurgaon, the 83-year-old Krishnan recalls the stormy run-up to that signature. “There was much resistance within the system when I prepared the note for the Cabinet’s consideration in May that year. I was flooded with ‘queries’ from senior officers,” he says.

His years in the bureaucracy had taught him to read the signs: ‘queries’ were just a way of conveying that he had to go slow. “But I replied within 24 hours to each of the queries and the order finally made it to V P Singh’s table.”

As secretary, Krishnan, not a backward himself, used to openly make his case for empowering the backward castes, minorities and Dalits. “Given the nature of the National Front government, I was worried that this arrangement (the coalition) would not last long, so I was working extra hard.”

The upheaval began soon after V P Singh made his August 7 announcement in the Lok Sabha on implementing the Mandal report — the BJP and the Congress railed against it, anti-Mandal protests broke out in the north, the government fell, and Chandra Shekhar took over as prime minister. While the south was not new to reservations, in the north, there were a rash of petitions in courts. “I knew Chandra Shekhar was anti-Mandal and would not want this to go through. So before I retired, I pushed a whole lot of data and information to the Supreme Court and dealt with all the objections.”

Krishnan recalls how he had to firefight a lot, even within the system. As immolations and protests started, he recalls, he had a meeting with then attorney general Soli Sorabjee, who asked him, ‘Bhai, what is this caste-shaste?’. “When I explained how fortunate he was to have been born a Parsi and not having to feel the full force of the caste system, he immediately came on my side.”

These days, Krishnan spends his days writing, drafting and pointing out the law and Constitution to all those who care to listen — state governments, courts, and other organisations.

Speaking of the far-reaching changes that Mandal brought to social and political lives, he says the “big thing” it did was to help recognise the idea of backwardness, as something that is weighed not just by access to money.

“It is important to know that in India a social system existed that sought to see vast number of people as lowly, inferior and backward. But for the debate that followed Mandal, stone-cutters, fishermen, boatmen… so many people who do such important tasks with their hands, would have existed unrecognised or unnamed,” he says.

Reported by Seema Chishti

The Indra Sawhney case

Now 64, Sawhney says the judgment has been “diluted and eroded for vote bank politics”.

Indra Sawhney: Took on the government, lent her name to the most famous of Mandal cases

‘Wanted issue of quotas settled’

Those were the days of fiery protests, rallies, demonstrations — and traffic snarls. As a young lawyer on her way to courts in Delhi, these disruptions forced her to reflect — and act — on what she saw. “Students were out on the roads, there were self-immolations… That’s when I decided to file the PIL,” says Indra Sawhney of her decision to file a PIL in the Supreme Court against the government. She says she wanted to “put to rest” the issue of reservation by seeking a definition of “backward classes” and whether more than 50 per cent of the seats could be reserved.

The case, and the judgment by a nine-judge Bench on November 16, 1992, became a landmark, with her name becoming a shorthand for what the courts had to say on the matter.

The 1992 judgment recognised socially and economically backward classes as a category, said caste could be a factor for identifying backward classes and recognised the validity of the 27 per cent reservation. Another phrase that gained currency through this judgment was the ‘creamy layer’ — those among the OBCs who had transcended their social backwardness were to be excluded from the reservation. The bench also laid down a 50 per cent limit on reservations and said that economic, social and educational criteria were needed to define backward classes.

Now 64, the senior lawyer says the judgment has been “diluted and eroded for vote bank politics”.

“Reservation was to be only for 10 years, but political parties just do politics to get votes instead of doing anything to uplift the backward classes,” says Sawhney.

Reported by Aneesha Mathur

Gujjar, Jat, Kapu, Maratha, Patidar agitations

From: August 9, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic :

A history of the Gujjar, Jat, Kapu, Maratha and Patidar agitations for ‘reservations,’ as in 2018

SC/ST quotas extended till 2030

Swati Mathur, Dec 11, 2019 Times of India

Lok Sabha passed the 126th Constitution Amendment Bill seeking to extend reservation to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes for another 10 years until January 2030, with all 352 MPs present voting in favour.

The debate on the bill, however, saw a sharply divided House, with opposition benches including Congress, DMK, NCP, TMC and CPM, as well as NDA ally Apna Dal (Sonelal) voicing concerns over the legislation seeking to end reservation for the Anglo-Indian community.

Law minister Ravi Shankar Prasad, however, argued that while there was a provision of reservation for Anglo-Indians in the bill, the government had not brought it to the House and still “deliberating on it”.

“The bill is very straight and unambiguous. But I want to say that the House will have to take a call one day on whether to grant reservation to the Anglo-Indian community,” he said.

Quoting the 2011 census, Prasad said India is home to 296 members of the Anglo-Indian community, a figure that was challenged by opposition parties. Congress MP Hibi Eden accused Prasad of “misleading” the House over the numbers and moved a privilege motion against the minister, arguing that quota for the community should continue.

Maratha reservation: arguments for and against

From: Prafulla Marpakwar & Sujit Mahamulkar, June 28, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

The Maratha reservation: arguments for and against (as in June 2019)

Debates in the Constituent Assembly

Patel and Ambedkar differed over reserved seats

Book: Patel, Ambedkar clashed over reserved seats, November 26, 2017: The Times of India

Sardar Patel played a decisive role in abolishing “reserved seats” for religious minorities which were approved by the Constituent Assembly and were part of the draft Constitution, says a new book which spotlights the turbulent post-Independence phase during which the country’s “electoral system” was finalised.

While the draft constitution provided for “reserved seats” for Dalits, Sikhs, Christians, Muslims and other minorities, the post-partition phase resulted in a strange combination of volatile circumstances — India was hitby “most violent human migrations in the history”, Gandhi was assassinated and “Sikhs were on the negotiating table whether to join the Indian Union or not”. “In the commotion, Sardar Patel decided to abolish reservedseatsfor all, including the Dalits in December 1948,” says thebook “Ambedkar, Gandhi and Patel: The making of India’s Electoral System” by IAS officer Raja Sekhar Vundru which was released by former chief election commissioner MS Gill and former planning commission member Bhalchandra Mungekar.

The book records that abolition of seats for Dalits was opposed by B R Ambedkar. Later, it was decided that all reserved seats should be abolished except for SCs.

Creamy layer

UPA trod softly, NDA caught in a bind

If the Supreme Court’s judgment extending ‘creamy layer’ to Scheduled Castes and Tribes has landed the NDA government in a quandary, it has the inadvertent hand of its arch-rival Congress.

When the apex court delivered the Nagaraj judgment in 2006, its unprecedented reference to ‘creamy layer’ in the context of Dalits touched off a furore. The champions of social justice sought redress, ranging from an appeal in the court to a legislation to overturn the judgment to buffering existing Dalit laws from judicial review by putting them in the 9th Schedule.

But none of it happened. Or, was required. A group of ministers headed by then foreign minister Pranab Mukherjee felt the Supreme Court’s view extending creamy layer to SCs/STs came in a case quite unrelated to the subject.

It referred the issue to then attorney general Milon Banerjee for his opinion.

Banerjee told the Centre that the apex court’s views were “obiter dicta” — an observation which is not part of the judgment. He also observed that the nine-judge Indira Sawhney judgment had excluded SCs/STs from a discussion on ‘creamy layer’ and a smaller bench could not overturn that judgment.

While the opinion set the controversy to rest and the government washed its hands of the matter, many felt the court could surprise the Centre and Dalits by clarifying its judgment and contradicting the AG’s view at a later date.

The contentious issue continued to gain momentum among groups eager for exclusionary concepts like ‘creamy layer’ in reservations for Dalits in recruitments and promotions.

As the Nagaraj judgment introduced a three-point criteria — data on backwardness, inadequacy of representation and efficiency — for reservation in promotions for SCs/STs, promotion quota came to a grinding halt across states.

The controversy was bound to go in appeal and the unsettled subject of ‘creamy layer’, paused only by a law officer’s interpretation, too was set to come up for discussion.

Crucially, the UPA unsuccessfully brought a constitution amendment bill in Parliament to undo the Nagaraj judgment’s prescription of three prerequisites for promotion quota. However, after the AG’s opinion, the ‘creamy layer’ issue was not touched.

Experts and social justice proponents feel if the subject was dealt with then or the Supreme Court had clarified the issue a few years ago, it may have been settled without much controversy.

The passage of time between the UPA regime and the NDA government has altered the ground realities.

During the UPA years, Dalit politics was still on the ascendant without a countervailing movement.

However, the emergence of upper caste agitations, as on view in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, have made it difficult to legislate in favour of Dalits without a political backlash.

When the apex court delivered the Nagaraj judgment in 2006, its unprecedented reference to ‘creamy layer’ in the context of Dalits touched off a furore

Economically deprived people: quota for

A history of the proposal

Though it’s the first time the Centre is attempting this, the demand for reservation for the poor among non-reserved sections is as old as quota itself. It figured immediately in the debates when reservation was conceived as part of affirmative action but did not gain traction barring odd attempts in Bihar and UP.

But with quota fires raging among dominant communities like Patels in Gujarat, Marathas in Maharashtra, Jats in Haryana and Kapus in Andhra Pradesh, the Modi government’s decision appears aimed at dousing agitations and winning them over.

The quota move appears designed to send a feel-good signal to upper castes like Brahmins, and Vaishyas, which form the core of BJP’s base but have lately expressed anger with the party in the wake of its quota actions favouring SCs/STs and OBCs.

The olive branch for upper castes gained currency in the late 1970s when OBC power began to assert itself and satraps felt a need to assuage forwards. As Bihar CM, OBC leader Karpoori Thakur’s formula included a share for poor among the upper castes. A similar move was cleared in Uttar Pradesh too. They, however, did not fly.

Narasimha Rao’s Mandal reservation order issued an office memorandum for 10% quota for EWS. Interestingly, chief ministers Ashok Gehlot of Rajasthan and Mayawati of UP on different occasions wrote to the Centre with such a plea. Even Congress in its Lok Sabha manifesto has promised it, starting in 1980.

But if governments were sceptical, it was possibly out of the fear they would face a stiff challenge in courts and would trigger a backlash among the reserved classes.

As a decision, the BJP initiative to amend the Constitution to provide quota for the poor marks the breaching of the red-line observed till now. It would cross the 50% quota ceiling fixed by the Indira Sawhney judgment of Mandal commission and test the constitutionality of providing quota on economic basis.

And yet, the political potential of such a move can hardly be emphasised enough. Quota has been the panacea to many a political problem. Not only among backwards, but also upper castes, like Jats were promised reservation by BJP in 2003 and Congress declared them OBC ahead of 2014 polls.

1991, 2003, 2006: previous attempts

Ahead of the 2019 General election and after getting a reality check in the polls from Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, the Modi Government has cleared 10 percent quota in government jobs and education for the ‘economically weaker’ sections in general category. The proposed reservation is above the existing 50 percent reservation quota for the Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs) and Other Backward Classes (OBCs). The proposed reservation if passed will take the total reservation to 60 percent.

Eligibility for the quota

Any person who belongs to the upper caste including Brahmins, Rajputs, Marathas, Jats, with an annual income below Rs 8 lakh and does not own agricultural land more than five acres are eligible to get the benefits of the quota. The other criteria are that the person should not own a flat of 1,000 sq ft.

So far, in India, the reservation is only given to the citizen on the basis of social and educational backwardness. But it is not the first time when a reservation based on the economic criteria is proposed by the government. The first proposal came in 1991 by the PV Narasimha Rao government to give a 10 percent reservation but it was rejected by the apex court. Coming back to 2019, regardless of whether the bill Supreme Court passes or strikes down the decision, here’s a look at the times when the government attempted to introduce reservation for the economically backward but failed.

Narasimha Rao led Congress Government, 1991

In 1991, the Congress government headed by the Narasimha Rao was the first time ever a government came with the idea to grant reservation to those belonging to upper caste but are economically weaker. However, in 1992, the Supreme Court in the Indra Sawhney case struck down the proposal stating separate reservation for economically weaker among forward castes is invalid.

Atal Bihari Vajpayee led BJP Government, 2003

In 2003, a year before the General Elections, the BJP Government led by Atal Bihari Vajpayee appointed a Group of Ministers (GoM) to come up with ideas that can be implemented for the poor among the upper castes. The GoM included prominent leaders including the then Deputy PM LK Advani, Law Minister Arun Jaitley, Finance Minister Jaswant Singh, and Railway Minister Nitish Kumar. In January 2004, a task force was set up to work on the criteria for the reservation for the economically backward section. But nothing came up and there are no records on submission of any reports submitted by the task force. End result? The Congress-led UPA-I took over the BJP government in the 2004 general election.

Manmohan Singh led Congress Government (2006 – 2013)

In 2006, the Congress-led UPA 1 government-appointed commission to study separate reservation for economically backward people from the upper castes. The government led by Manmohan Singh set up a commission to suggest criteria for economically backward classes and come up with welfare measures. The commission submitted the report in 2010, when the UPA – II was in power,s suggesting to carve out a category that would provide the economically backward classes the same benefits of the Other Backward Classes (OBCs). However, the proposal was discussed in 2013, a year before the 2014 General Elections but was put on hold as it would need a constitutional amendment to get around the apex court’s 50 percent cap for quotas.

Legal barriers

Legal experts unsure quota will clear judicial test, January 8, 2019: The Times of India

After the Union cabinet cleared the bill to provide reservation for economically weaker sections from upper castes, some constitutional and legal experts were not sure whether the legislation would pass the judicial test as quota exceeding 50% would be in violation of the apex court verdict that had placed the cap.

Some experts said the Constitution does not recognise economically weaker sections as a separate class for providing preferential treatment. They said the issue will have to be finally adjudicated by the Supreme Court after the bill is passed by Parliament.

“No such class is recognised by the Constitution. The government has to amend Article 15 and 16 to provide quota on the basis of economic status. It may not pass the legal test when the issue will be examined by court, which had repeatedly said that reservation cannot go beyond 50%,” senior advocate Amrendra Sharan said.

Sharan said the Constitution provides reservation for only three social classes—Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Socially and Educationally Backward Classes.

Former Lok Sabha Secretary-General Subhash C Kashyap said the bill had to be passed by both Houses of Parliament and only then it could be challenged in court. He said he had not seen the bill and would comment only after examining its provisions but the issue would have to pass through the judicial scanner before implementation.

Former HC judge and senior advocate Ajit Sinha said the bill was not discriminatory as the benefit of reservation would be extended to people irrespective of their religious affiliation and only on the basis of economic status but if the overall reservation goes beyond 50%, it could be struck down by the court.

BJP/ NDA’s 2019 announcement

Shankar Raghuraman, Almost All Indians Can Now Have A Quota, January 8, 2019: The Times of India

95% will meet income cut-off

The new quota announced by the government will cover practically all of the population not already covered by reservations, reveals an analysis of the exclusion criteria spelt out for the quota. With this, therefore, almost all of India’s population will be entitled to one quota or the other.

Here’s how that works out. The income criterion to be used is an annual household income of Rs 8 lakh. Data from the I-T department as well as reports from the NSSO show that at least 95% of Indian families will fall within this limit.

An annual household income of Rs 8 lakh would mean a per person income of a little over Rs 13,000 per month assuming a family of five. The top-most income slice for which the NSSO survey of 2011-12 (the latest) gives data is of over Rs 2,625 per person per month in rural areas and Rs 6,015 in urban areas, both well under this mark. Yet this top slice has a mere 5% of the households in it.

Further, for 2016-17, just under 23 million individuals declared incomes of over Rs 4 lakh. Even assuming two such individuals in each family, that would mean about 1 crore families at best would be over the Rs 8 lakh cut-off. That translates to roughly 4% of Indians.

Incidentally, government data released on Monday shows a per capita income of Rs 1.25 lakh. That translates to Rs 6.25 lakh for a family of five. Thus, a household that gets Rs 8 lakh a year would be significantly above the national average, certainly not poor.

The land-holding criterion is just as liberal. The agricultural census for 2015-16 revealed that 86.2% of all land- holdings in India were under 2 hectares in size, or just under 5 acres. So, once again the bulk of the population qualifies for the new quota under this.

A third criterion is that the size of the house should not be over 1,000 sq.ft. The NSSO report on housing conditions in 2012 shows that even the richest 20% of the population had houses with an average floor area of 45.99 sq.m, which is almost exactly 500 sq.ft. That is barely half the ceiling being imposed. Here, too, at least 80%, and more likely well over 90%, would be eligible.

What this means is that the new quota will be available to almost anybody not currently covered by the SC/ST or OBC reservations. SCs and STs constitute around 23% of the population while OBCs make up another 40-50% though no official data is available. That leaves about 27-37% currently not entitled to any quota. Considering that the big slice of all ‘open’ jobs or seats go to these sections anyway, and that the relatively better off among them are better placed to make use of opportunities, it is not clear just how much the new quota will change things on the ground.

CPM amendment to quota bill rejected

January 10, 2019: The Times of India

CPM moved an amendment to the contentious Constitution (124th Amendment) Bill, 2019, demanding the bill include in its purview “economically weaker” scheduled castes, tribes and OBCs while providing reservations to economically weaker sections in private educational institutions. Both amendments were subsequently rejected during the vote on the bill.

The amendment was moved by Kerala MP T K Rangarajan and K K Ragesh in Rajya Sabha, a day after a similar request by CPM MP P Karunakaran was turned down by Lok Sabha Speaker Sumitra Mahajan on grounds that it was filed “too late”. Rangarajan also demanded that the bill be sent to the select committee for further scrutiny.

Opposing the denial of permission, CPM MPs had protested that the government had moved the constitutional amendment bill at short notice and by dispensing with all parliamentary procedures. The left party also highlighted that constitutional amendments had never before been moved without first being discussed and listed in the Business Advisory Committee.

CPM also argued that while they have supported reservation for economically backward classes since Mandal Commission, the proposed amendment to the Constitution has several incongruities, including in its reference to who qualifies as “economically weaker”.

Likely impact of Jats, Marathas, Patidars

Though the 10% quota for the economically weak has brought the spotlight back on dominant castes such as the Jats, Marathas and Patidars demanding reservation, it is clear that at least in Haryana, the Jats would not immediately benefit from the Centre’s move.

The Marathas in Maharashtra are hopeful they can now strengthen their case in the Bombay high court, where the 16% reservation given to them last year by the state has been challenged, and in Gujarat Hardik Patel sees the new law as endorsing his own demand for a Patidar quota.

The Jats will not benefit as the community is notified as Backward Class under the Haryana Backward Classes Act of 2016, while the Centre’s constitutional amendment bill makes it clear only the economically weak from the general category will be covered under the 10% quota.

At the state level, Haryana already has a quota for the economically weak from among the unreserved groups. But the Punjab and Haryana high court had in August 2017 restrained the Haryana government from extending benefits of this 10% quota to castes notified as backward. The court’s word came on a plea against issuing of economically weaker section certificates to those from the Jat community. The HC has also stayed the 10% quota for Jats in government jobs and education under the 2016 Act.

Satya Paul Jain, additional solicitor-general of India, said as far as the Centre is concerned, Jats may not have any problem in getting reservation under the new category. “However, the state’s notification declaring them backward may require some judicial interpretation,” Jain said. Baldev Raj Mahajan, advocate general, Haryana, said the state is aware of this legal complication but would ensure Jats and five other communities get benefits at least under one quota.

Vinod Patil, convenor, Maratha Kranti Morcha, said the new quota will help create the ground for the state to cross the 50% ceiling cited in the challenge to the Maratha quota. Maharashtra’s total quota is at 68% after the state brought in the Maratha quota. Plus, he said, the Central quota can be availed of by the community now too. Revenue minister Chandrakant Patil said the Centre’s quota meant reservations for those in the state could go up to 78%.

Hardik Patel said if the Centre were able to implement the 10% quota, “I will stop my agitation and support BJP.” But he added the new quota was a “lollipop” and his stir would continue.

In Haryana, crorepatis are eligible for EWS quota/ 2019

February 14, 2019: The Times of India

Even crorepatis — individuals or a family having immovable property worth Rs 1 crore — will be considered for the economically weaker section (EWS) quota in Haryana. However, if the value of the assets is even one paisa above Rs 1crore, the family will not make the cut.

The criteria to provide 10% quota under the newly-carved EWS category was approved on Wednesday by the Haryana cabinet at its meeting in Chandigarh. The cabinet, headed by CM Manohar Lal Khattar, decided to grant reservation to the extent of 10% each to EWS in direct recruitment to Group A, B, C and D post in all departments, boards, corporations and local bodies of the state government and for admission to all gover nment or gover nment-aided educational institutions.

As per the approved criteria, a family for this purpose would include the person who seeks benefit of reservation, his/her parents, spouse and children and siblings aged below 18.

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s views

2015

The Times of India, Sep 22 2015

Row erupts over Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh chief's quota remark

The call for a committee of politically neutral persons to examine criteria for reservations is, in fact, part of a 1981 Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh resolution displayed prominently on the organization's website. The resolution, while supporting reservation as a means to achieving a more equal society , says, “The committee should also recommend necessary concessions to the other economically backward sections with a view to ensuring their speedy development.

“The ABPS (all India representative council of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh)agrees with the prime minister's (Indira Gandhi) viewpoint that reservations cannot be a permanent arrangement, that these crutches will have to be done away with as soon as possible, and that because of this arrangement, merit and efficiency should not be allowed to be adversely affected. The Sabha appeals to all other political parties and leaders as well to support this viewpoint and initiate measures to find a solution to the problem.“

Sources said Bhagwat's remarks related to the argument -often raised even by reservation beneficiaries -that quota benefits are cornered by some influential castes and need a second look to protect the really vulnerable. The 1981 resolution supports reservations but expresses concern that quotas have been a “tool of power politics and election tactics“ generating ill will and conflict in society.

Scheduled Communities

In Bihar, Jharkhand, WB: Planning Commission paper

1932, 1936

The scheduled communities evolved out of the British colonial concern for the Depressed Classes who faced multiple deprivations on account of their low position in the hierarchy of the Hindu caste system. The degrading practice of untouchability figured as the central target for social reformers and their movements. The issue acquired strong political overtones when the British sought to combine the problems of the Depressed Classes with their communal politics. The Communal Award of August 4, 1932, after the conclusion of two successive Round Table Conferences in London, assigned separate electorates not only for the Muslims, Sikhs, Christians and several other categories, but also extended it to the Depressed Classes. This led to the historic fast unto death by Gandhi and the subsequent signing of the Poona Pact between B.R. Ambedkar and Madan Mohan Malviya on September 24th 1932. According to this agreement a new formula was evolved in which separate electorates were replaced by reserved constituencies for the Depressed Classes. The actual process of ‘scheduling’ of castes took place thereafter in preparation of the elections in 1937.*

{As per Government of India (Scheduled Castes) Order of 1936 read with Article 26(i) of the First Schedule to Government of India Act 1935, Scheduled Castes meant `such castes, races or tribes, or parts of or groups within castes, races or tribes, being castes, races, or tribes, or parts or groups which appear to His Majesty in Council, to correspond to the classes of persons formerly known as `the depressed classes’, as His Majesty in Council may specify’. (Cited in Chatterjee 1996 vol. : 162).}

Ambedkar, who was the principal crusader against untouchability, assumed the historic role of drafting the Indian Constitution of free India. He introduced the famous Article 11 of the Drafting Committee on 1st November 1947 which carried through the following resolution :

“Untouchability is abolished and its practice in any form is forbidden. The enforcement of any disability arising out of ‘untouchability’ shall be an offence which shall be punishable in accordance with law” (Rao 1966 : 298).

After 1947

Unlike the British pre-occupation with the scheduling of castes in preparation for separate communal electorates, which mainly entailed, by stages, the elimination of tribal communities from the fold of Depressed Classes, the proper task of scheduling of tribes took place in 1950 with the new Constitution. This is hardly surprising in view of numerous tribal insurrections against British exploitation and domination. A series of 12 Constitution (Scheduled Tribes Orders) and amendments were passed between 1950 and 1991 covering various States and Union Territories.

In 1991 the Scheduled Caste (henceforward SC) population was 138,223,000 (nearest ‘000), accounting for 16.48 percent of the total population of the country. Four important demographic features draw our attention at this stage :

1) The States which exceeded the national proportion of SCs and consequently had the highest concentration of SCs were : Punjab (28.31%), Himachal Pradesh (25.34%), West Bengal (23.62%), Uttar Pradesh (21.05%), Haryana (19.75%), Tamil Nadu (19.18%), Delhi (19.05%), Rajasthan (17.29%) and Chandigarh (16.51%).

2) States which have substantial SC population (more than 10m) are : Uttar Pradesh (29.3m) contributing 21.18% of national SC population; West Bengal (16.1m) contributing 11.63%; Bihar (12.6m) contributing 9.10%; and Tamil Nadu (10.7m) contributing 7.75% of the SC population of India. A State may be amongst those having the most numerous SC population, and yet its proportion to the total population (of the State) may be lower than the national average. For example, erstwhile Bihar was a populous SC state, yet only 14.55% of its population was SC.

3) The State having the highest number of SC communities is Karnataka (101) with an SC population below 10m. (7.4,), with proportion of SCs to the population of the State slightly below the national proportion (16.38%) and contributing only 5.33% of the total country’s SC population. Karnataka is followed by Orissa with 93 SC communities; Tamil Nadu with 76; Kerala with 68; Uttar Pradesh with 66; Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan and West Bengal with 59; and Himachal Pradesh with 56.

Thus States with the largest multiplicity of SC communities, need not be amongst the most populous SC States, nor among those whose contribution to the national SC population are among the highest.

4) Conversely, States making the largest contributions of SC populations to the national SC total need not have the highest proportions of SCs or the largest number of SC communities within their States. These States are Uttar Pradesh (21.18%), West Bengal (11.63%), Bihar (9.10%), Tamil Nadu (7.75%), Andhra Pradesh (7.66%), Madhya Pradesh (6.96%) and Maharashtra (6.34%).

The Scheduled Tribe (henceforward ST) popula tion of India is almost 50 percent less (67,758,000, nearest ‘000), than the SC population of India, constituting 8.08 percent of the country’s total population. The picture here is quite interesting. In sharp contrast to SCs, a number of States/Union Territories have extraordinarily high concentrations of tribal population (i.e. tribal population as proportion of total population of the States/Union Territories (henceforward UTs). These States/UTs are : Mizoram (94.75%) with a population of only 654,000; Lakshadeep (93.15%) with a meagre population of 48,000; Nagaland (87.70%) with a population of 1,061,000; Meghalaya (85.53%) with a population of 1,518,000; Dadra and Nagar Haveli (78.89%) with a population of 109,000; and Arunachal Pradesh (63.66%) with a population of 550,000. Then there is a steep drop with Manipur (34.41%) having a population of 632,000; Tripura (30.95%) with a population of 853,000. These eight States/UTs having tribal concentrations varying from 30.95% to 94.75%, have a total population of 5.5m, which is only 8.1 percent of the total tribal population of the country. Conspicuously, in the most populous tribal States, the concentration of ST population is very much lower, though substantially higher than the national proportion. The largest tribal population is in Madhya Pradesh (15.4m) constituting 23.27 percent of the population of the State and 22.73 percent of the tribal population of the country. This is followed by Maharashtra (7.3m), Orissa (7.0m), Bihar (6.6m), Gujarat (6.1m), Rajasthan (5.5m), Andhra Pradesh (4.2m), West Bengal (3.8m) and Assam (2.9m). Finally, the States/UTs with the highest number of tribal communities are : Orissa (62); Karnataka and Maharashtra (49); Madhya Pradesh (46); West Bengal (38), Tamil Nadu (36); Kerala (35); Andhra Pradesh (33); and Bihar (30).

What is extraordinary in this overall pattern is that none of the States with the largest tribal population (2m and above) and those having the most numerous tribal communities, figure among States/UTs having the highest concentration of STs. Few, if any, countries can parallel this complex ethno-demography.

What is unique in India, is the existence of the least populous self governing, politically empowered, tribal States mostly in the north east, together constituting a negligible proportion of the tribal population of India, nevertheless being protected through Constitutional safeguards against ethnic swamping by the other communities in a country with a bursting, burgeoning billion population. They have evolved out of their specific historical circumstances which had posed basic problems of their integration with the rest of the country.

It is, by and large, the bulk of the tribal population in the more populous heterogeneous States that have encountered the serious problems of social and economic derivation and development.

References

Rao, Shiva The Framing of India’s Constitution, New Delhi, IIPA, 1966.

Chatterjee, S.K. Scheduled Castes in India Vol.1, New Delhi, Gyan Prakashan, 1996.

-do- Scheduled Castes in India, Vol..4, New Delhi, Gyan Prakashan, 1996. Chakraborty G. P.K. Ghosh Human Development Profile of Scheduled Castes and Tribes in and Selected States, New Delhi, NCAER, 2000.

Sachidanand R.R. Prasad Encyclopaedic Profile of Indian Tribes, New Delhi, Discovery and Publishing House, 1996

See also

Caste-based reservations, India (legal position)

Caste-based reservations, India (history)

Caste-based reservations, India (the results, statistics)

The Scheduled Castes: statistics

Scheduled Castes of Kerala (list)

Scheduled Castes in Tamil Nadu