Burma, Agriculture 1908

(→Forests) |

(→See also) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by one user not shown) | |||

| Line 1,196: | Line 1,196: | ||

executed, as a rule, in high relief, and the work, when well done, is | executed, as a rule, in high relief, and the work, when well done, is | ||

singularly effective. | singularly effective. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Famine== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Its abundant rainfall has placed Lower Burma, humanly speaking, | ||

| + | wholly out of reach not only of real famine but even of such distress | ||

| + | as would follow on a partial failure of crops. In the | ||

| + | southern half of Upper Burma the monsoon is often | ||

| + | fickle and untrustworthy, but even here famine in the Indian accepta- | ||

| + | tion of the term is practically unknown. Floods and insect pests work | ||

| + | no widespread havoc among the crops. Drought has in the past | ||

| + | temporarily disorganized the Districts of Meiktila, Yamethin, Minbu, | ||

| + | Magwe, Shwebo, Sagaing, Myingyan, and Mandalay, and has rendered | ||

| + | the opening of relief works necessary ; but every year the improvement | ||

| + | of communications and the construction of irrigation works thrust | ||

| + | famine proper farther and farther out of the category of probable | ||

| + | natural scourges. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The recently opened canal has rendered parts of | ||

| + | Mandalay District immune ; and the next few years should see the | ||

| + | same result achieved in parts of Minbu and Shwebo. Meiktila, Yame- | ||

| + | thin, and Sagaing are traversed from end to end by one, if not two, | ||

| + | lines of railway ; and Magwe lies between the railway line and the river | ||

| + | Irrawaddy, and is, after Yamethin, the closest of the dry Districts to the | ||

| + | well-watered areas of Lower Burma. That scarcity has left its mark | ||

| + | upon Upper Burma is, however, indubitable ; for, though mortality | ||

| + | from famine (direct or indirect) is infinitesimal, failure of crops is | ||

| + | largely responsible for the relatively small rate of increase that has | ||

| + | taken place during the past ten years in the population of the dry zone | ||

| + | (12 per cent, as against 27 per cent, in the moist Districts of Lower | ||

| + | Burma), and no amount of irrigation works and railway lines will be able t(; place some of the arid areas in a position to compete with the | ||

| + | wetter portions of Burma or to free them from periods of anxiety. | ||

| + | Before annexation, famines in Upper Burma were of not infrequent | ||

| + | occurrence. | ||

| + | |||

| + | No reliable details regarding their area and intensity are | ||

| + | forthcoming, but there can be no question that they were at times very | ||

| + | severe. Between the annexation and 1891 there was no extensive | ||

| + | scarcity. In 1887 there was a partial failure of crops in a portion of | ||

| + | what is now Shwebo District, but relief works were not considered | ||

| + | necessary. In 1891 deficient rain caused a shortage of crops in the | ||

| + | greater part of the dry zone. From December, 1891, to March, 1892, | ||

| + | distress was acute over an area of more than 80,000 square miles, | ||

| + | emigration on a large scale to Lower Burma commenced, and it was | ||

| + | necessary to open relief works and grant gratuitous relief, though | ||

| + | recourse to the latter step was not frequent. The number of persons | ||

| + | on relief works during the period of greatest depression was over | ||

| + | 20,000, and the cost of the measures taken to combat the scarcity | ||

| + | amounted to more than 15 lakhs. The period between 189 1-2 and | ||

| + | 1896-7 was one of indifferent harvests in Upper Burma. In 1895-6 | ||

| + | there was a partial failure of crops, and in 1896-7 the early rains failed | ||

| + | in the Districts of Meiktila, Myingyan, and Yamethin. The area | ||

| + | affected by the drought covered 5,300 square miles, with a population | ||

| + | of 528,000 persons. The first relief works opened were unimportant; | ||

| + | but later it was found that more extensive operations would be needed, | ||

| + | and work was started, first on the earthwork of the Meiktila-Myingyan | ||

| + | Railway, and then on a large tank in Myingyan District. From | ||

| + | December, 1896, to February, 1897, the average of persons in receipt | ||

| + | of relief was 28,000. There was a diminution during the next few | ||

| + | months, but by August the aggregate had risen to 30,000. The | ||

| + | grant of gratuitous relief was found necessary, and the expenditure | ||

| + | on aid of all kinds to the sufferers was a little over ^\ lakhs. Since | ||

| + | then there have been threatenings of scarcity, but no real distress, in | ||

| + | Upper Burma. Even the most serious scarcity experienced so far in | ||

| + | the Province must, when judged by Indian standards, be looked upon | ||

| + | as slight. None of the droughts has added appreciably to the death- | ||

| + | rate of the Province, no deaths from privation have been recorded as | ||

| + | a result of their occurrence, and no visible reduction of the birth-rate | ||

| + | has followed in their wake. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The construction of irrigation works is the principal measure adopted | ||

| + | to minimize the results of deficient rainfall in the famine-affected areas. | ||

| + | These works are on a large scale, for experience has shown that tanks | ||

| + | and the like with an insignificant catchment area cannot be relied upon | ||

| + | in the lean years. The necessity for adequate professional knowledge | ||

| + | in the matter was one of the causes which led to the establishment in | ||

| + | 1892 of a separate Public Works Irrigation Circle, on the officers of | ||

| + | which devolves the duty of designing and carrying into execution | ||

| + | schemes for supplementing the existing water-supply of the more arid | ||

| + | tracts. The weekly crop reports compiled by Deputy-Commissioners | ||

| + | from data furnished by township officers regarding the price of grain, | ||

| + | the nature of the weather, the existence of conditions likely to affect | ||

| + | the harvest, and cognate matters, enable a constant watch to be kept | ||

| + | on the economic condition of the agricultural community and give the | ||

| + | earliest intimation of any possible scarcity of crops. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==See also== | ||

| + | |||

| + | For a large number of articles about Burma, extracted from the Gazetteer of 1908 (as well as other articles on Burma) please either click the 'Myanmar' link (below, left) and go to Burma(under B) or enter 'Burma' in the 'Search' box (top, right). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Burma, Physical Aspects 1908]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Burma, History 1908]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Burma, Administration 1908]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Burma, Commerce and Trade 1908]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Burma, Communication 1908]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Burma, Agriculture 1908]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Burma, Population 1908]] | ||

Latest revision as of 23:10, 13 November 2014

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

[edit] Agriculture

Agriculture, as already stated, affords the means of support to over 66 per cent, of the population of Burma, and is the subsidiary occupation of a further portion of the community. Cultivation is regulated more by rainfall than by the conformation of the surface of the soil. Rice is grown wherever there is sufficient moisture and land in any way adapted to its cultivation. In the dry zone of Upper Burma, sesamum, maize, jo7var, cotton, beans, wheat, and gram largely take the place of rice ; but these alternative products have been practically forced upon the Upper Burma cultivator by climatic con- ditions, for it is an almost universal rule that where rice of any kind can be cultivated, it is raised to the exclusion of other and apparently more appropriate 'dry crops.' Throughout Lower Burma the rainfall is ample for rice cultivation, and little else but rice is produced there, and the same may be said of a substantial portion of the wet division of Upper Burma. Rice cultivation in Burma is of two main classes : namely, le ('lowland') and taungya ('hill-slope'). The .r^ crops, such as sesamum, cotton, and jowar, cover the rolling uplands of the dry Districts of Upper Burma and so much of the plain as cannot be brought under rice cultivation. \Vheat and gram are grown in the better kinds of lowland soil ; and beans and maize, with a host of other minor crops of the class ordinarily known as kainggyun, are harvested in the rich alluvial soil left behind as the waters of the rivers recede from their flood limits during the dry season.

Rice is the staple food-grain of the Province. To eat a meal of any kind is, in Burmese, to * eat rice ' {tamin so). There are numerous varieties of rice, distinguishable from each other by colour, texture, consistency when cooked, and the like ; but their names are largely local and, from an agricultural point of view, their differences are not of special importance. A more suitable classification, after that which separates the plain from the upland rice, is by harvests or seasons. There are three main harvest classes : kaukkyi, the big or late rains rice, which is sown in nurseries {f>yogin) at the beginning of the monsoon, transplanted during the rains, and reaped during the cold season ; kaiikyin, the quick-growing or early rains rice, which is sown in May- June and gathered during the height of the rains ; and mayin, or dry- season rice, which is sown during the cold season on the edges of meres or other inundated depressions from which the water is receding, and is garnered about the commencement of the rains. Other harvest classes are known as kauklat and kaukti. Of these, the kaukkyi pro- vides the bulk of the rice of Burma. Very little else is cultivated in the Lower province, and it is practically this crop alone that is exported. It is longer in the stalk than the other kinds and takes longer to mature. In Upper Burma the climate does not always lend itself to kaukkyi cultivation, and recourse has to be had there to the inferior varieties. Taungya, or ' hill rice,' is sown, as soon as the rains set in, on hill slopes which have been cleared and fired during the hot season. The seed is not transplanted from nurseries, as is usual in the case of le rice, but is scattered broadcast or dibbled in the ash-impregnated soil, and the crop is reaped towards the close of the rains. The system of cultivation adopted is to the last degree wasteful, for the soil is soon exhausted and constant moves have to be made by the tatingya-c\xiK.&x to new and uncleared hill-sides.

There is nothing particularly attractive in the paddy-fields of Burma. A stretch of typical delta rice country in the early rains is a dingy expanse of mud and water, studded with squat hamlets, and cut up by low earth ridges into a multitude of irregular polygons through which mire-bespattered plough bullocks wade. Later on, with the transplant- ing, the plain grows green ; and, as the young plants accustom them- selves to their surroundings, this hue becomes more pronounced, till the cold season draws near and the expanse takes on a tinge of yellow that recalls the approach of the wheat harvest of England ; but here there are no undulations to break the dull uniformity of the outlook, no trim hedges, no variety of crops. All is one dead level away to the horizon. It is very little more picturesque in the uplands. Among the hills the taungya patches are conspicuous ; but unsightly blackened tree-stumps stand up out of the grain, and there is an air of desolation and unkeniptness about the clearings that nothing in the way of colouring or surroundings can redeem.

Jowdr or millet {Sorghum vulgare) is the main subsidiary food-crop in the dry zone of Upper Burma. In some of the arid upland tracts this grain takes the place of rice as the ordinary food of the household ; but ordinarily it is not regularly eaten, and is often grown simply as fodder for cattle. There are two main varieties of millet : the kun- pyaung which has a husk, and the sanpyaung which has none. The plant, which is not unlike maize, grows to 8 or 10 feet' in height. It is sown on all descriptions o{ ya land in July and x^ugust, and is cut towards the end of the cold season. There was a large export oi Jowdr to India during the recent famine years.

Sesamum {h/ian) is for the most part, like millet, essentially a dry area crop. There are two distinct sesamum harvests, that of the early sesamum or hnatiyin and that of the late sesamum or hnaiigyi, the former being more generally grown. The latter is sown towards the close of the rainy season and reaped during the cold season, while the hnanyin is gathered during the rains. The plants, when mature, range in height from 2 to 5 feet and bear white flowers. Sesamum is culti- vated for the sake of the seed, which yields an oil much affected by the Burman in cooking. Oil-presses on the pestle-and-mortar prin- ciple, usually worked by bullocks, are common in the majority of the villages where sesamum is grown.

Of the kaing or riverain crops none is more conspicuous than maize {pyaungbu), which carries glossy green foliage and rises to a considerable height, either alone or in conjunction with a form of climbing pulse, the growth of which its stalks materially assist. The maize cob is largely eaten green, as a delicacy, and the husk or sheath when dried is used for the outer covering of Burmese cheroots. Its stalks, like those of Jowdr, are excellent fodder for cattle. It is sown as the water falls and is cut during the dry season.

Of peas and beans, which are also the product of river land inun- dated during the rains, there are numerous varieties, of which some of the best known are pegyi, pegya^ 7>iatpe, and sadawpe. The sowing of this form of kaitig crop takes place in October, and the harvest is gathered just before the hot season begins. There is a considerable export oi pegya {Phaseoliis lunatus) to Europe for cattle fodder.

Cotton is grown systematically only in certain special tracts of the dry zone. It is sown on high land, as a rule, early in May, and picking commences about October and is continued at intervals till the end of the year. In Thayetmyo District picking appears to be continued up to a later date than in Upper Burma. The cotton is short-stapled as a rule. It is cleaned locally, either by hand or in cotton-ginning mills, and sent to both China and India.

Tobacco is ordinarily sown in nurseries on inundated alluvial land in September and October, and planted out in December. The crop is one that needs careful attention ; and weeding, pruning, and hoeing are constantly necessary. In March and April the leaf is ready for picking. It is then plucked, roughly pressed, and dried in the sun, but no regular curing operations are undertaken. The stalks are used for smoking as well as the leaves. It is grown solely for local con- sumption.

A level black soil known as sane is the best soil for gram and wheat. Both crops are grown on alluvial land, and are sown at the close of the rainy season and harvested at the beginning of the hot season. Wheat, which in Burma is of the bearded kind, is grown only in a few limited tracts in the dry zone ; the cultivation of gram is more widespread.

Throughout the dry zone the toddy-palm {Borasstis flabellifer) is a feature of the landscape, and the tapping of this useful tree affords employment to a large proportion of the residents of the Districts in which it grows. Tapping commences in February and continues till July. The juice when extracted is either fermented and made into tdri^ or is boiled down into molasses or jaggery {fanyet). The leaves are used in the dry zone for thatching purposes.

Among the other products of the country may be mentioned chillies, pumpkins and gourds, betel-vines and the areca-nut, sugar-cane, and onions. Plantains are successfully cultivated on a small scale in nearly every village, and on a larger scale in specially suitable tracts ; mango- trees abound, though, except in the neighbourhood of Mandalay, the fruit is not as a rule of any exceptional quality. Prome has long been famous for its custard-apples, and the southern portion of the Tenas- serim Division has achieved a local notoriety for its mangosteens and durians. Pineapples are common, and are cultivated in enormous quantities in the immediate neighbourhood of Rangoon. Oranges of good quality are grown in Amherst, in the Shan States, and in Toungoo. Tea-growing is systematically practised in the Shan States by the Palaungs ; but the industry has never been able to attract European capital, and is still conducted on purely native lines. Coffee has, on the other hand, been worked on the Ceylon and Indian systems, and was very successful in Toungoo District until attacked by leaf disease. Opium is grown freely in portions of the Shan States, but the drug is extracted almost solely for home consumption. There is no regular cultivation of fibres on a large scale, though the forests of the Province abound in shaiv and other fibrous products. ^a«-hemp is, however, grown to a considerable extent in Tavoy.

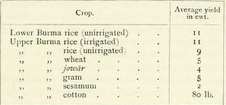

The average yield in cwt. per acre of the principal crops of Burma is as follows : — •

Ploughs and harrows are used for breaking up the soil and preparing it for the reception of seed. Ploughs {te) are either of wood, or of wood and iron, chiefly the latter ; harrows (tundoii) are almost invari- ably of wood only. The latter consist of a single pole or bar with teeth of cutch ox padauk wood fixed at intervals along its length. They are heavy and cumbrous, and receive the additional weight of a man who stands upon the implement in its progress across the soil. A pri- mitive kind of roller or clod-crusher {kyafidon) is used in Upper Burma and in portions of the Lower province, where it is known as setdon. Various forms of knives and sickles are used for reaping, weeding, and the like. They are all straight or slightly curved ; the sickle of English husbandry with a semicircular blade has not yet found general favour. Hoes and mattocks are employed extensively for agricultural purposes, the purest indigenous form being the tuywin, a spud-like implement with a straight shaft and a small slightly concave blade, of little use except for digging holes and grubbing up weeds. Threshing is not as a rule done by hand. The grain is trodden out by cattle ; winnowing is carried out with the aid of trays of woven bamboo ; and paddy is ordinarily husked in wooden mortars, the pestle consisting of a block of wood at the end of a heavy bar working on a lever, which is raised and lowered by the weight of the operator's body as he steps on and off the farther end of the bar. The Burman's conservative tendencies are nowhere more apparent than in his dealings with the soil, and the introduction into the country of novel agricultural appliances is slow. The greater proportion of the cultivator's implements are still eminently primitive, and are not likely to alter materially in character for some time to come.

Cow-dung is used to a certain extent for manure in some Districts, but the labour involved in carrying the manure from the cattle-pens to the fields appears to be an insuperable obstacle in the way of manuring on a methodical and uniform system. As a rule the nurseries receive most attention when any manuring is done. The only other measure taken to fertilize the paddy-fields is to burn the stubble during the dry season and to leave the ash to enrich the soil.

In Lower Burma, where there is only one main crop of importance and the soil is extraordinarily fertile, the question of rotation of crops is not one which concerns the agriculturist to any appreciable extent. In Upper Burma, on the other hand, and especially in the dry zone, experience has taught the husbandman that there is a limit to the recu- perative power of much of the non-inundated land ; that some crops exhaust the soil more than others ; and that regard must be paid to this fact in cropping the poorer classes of fields. Sesamum, for instance, absorbs an exceptional quantity of nourishment from the soil, and is not generally grown two successive years on the same land. In some cases two fallow years are allowed after a sesamum year, in some more. Occasionally joivdr or cotton or both take their turn before the fallow period commences. In better kinds of soil sesamum and joivdr are cropped in alternate years. In the sane (black soil) tracts wheat and gram alternate to a certain extent, and millet often succeeds cotton before a fallow. As a rule, however, even where conditions demand an economical system of rotation, the order of tillage observed is more or less haphazard and the most is not made of the properties that the soil possesses.

The average area of a holding differs very greatly from District to District and tract to tract. The mean for Meiktila District is 7-7, that for Sagaing rather over 12 acres. In Pegu, in 1900, the average area of rice-land holdings was 26 acres, or more than double the Sagaing average. In certain localities, as, for instance, in Prome and Kyauk- pyu, it is even lower than in Meiktila ; and looking at the Province as a whole, and having regard to the numerical strength of the agricul- tural community and the area under cultivation, it would probably be safe to say that the general average falls between 10 and 15 acres. The total area under crop in 1903-4 amounted to 19,680 square miles, being 50 per cent, larger than that cropped ten years earlier. A portion of this increase must be attributed to more accurate surveys, but even so the growth is still substantial. In Lower Burma extension of cultivation was large in 1892-3; in 1893-4 it was less marked; while cattle-disease, and low prices induced by a paddy ring, sent the area cropped in 1894-5 down to more than 235 square miles below the previous year's figures. Since these years of depression, however, prices have ruled high, and the growth of cultivation in the Lower province has been calculated at the rate of 375 square miles per annum. In Upper Burma there has been a steady rise in the area under cultivation since the early post-annexation days, with only temporary decreases, owing to deficient rainfall, in 1895-6 and 1901-2.

The area under rice in 1903-4 was 14,540 square miles. Rice now covers over two-thirds of the cropped area in the whole of Burma, and in Lower Burma it forms more than eleven-twelfths of the total. Thus the history of the increase or decrease of cultivation generally is in Burma to all intents and purposes a history of the growth or shrinkage of the cultivation of rice. Jowar, gram, sesamum, sugar-cane, cotton, and tobacco all show increases. Maize, on the other hand, would seem to be declining in popularity. Joivdr showed a total of 1,633 square miles in 1903-4, representing an increase of 78 per cent, since 1894. In the case of sesamum the ten years in question have seen a growth of no less than 128 per cent, in the cropped area. On the whole, recent years have been favourable to the crops in both sections of the Province, and have enabled the cultivators to extend their holdings and clear available waste ground ; while scarcity in India has afforded a ready market for agricultural produce, notably food-grains.

The advantages of improvements in quality by a careful selection of seed have not been wholly lost sight of in the Province ; but where high prices are obtainable in the market for produce of almost any class, quantity rather than quality is the improvident husbandman's first and often his only thought. The Settlement officer of Prome wrote in his Revision Settlemefit Report (season 1 900-1) : —

' As a rule the seed paddy is merely taken from the store of wimsa, but in one kivin near Shwedaung a holding in an unpromising situation was found to be giving an unusually heavy crop, which the cultivators explained was due to the use of specially selected hand-picked seed grain. It is possible that this is not a solitary case, but no other happened to come to light.'

It is to be feared, however, that forethought such as this is likely to be the exception with the Burman for many years to come.

The Agricultural department is doing its best to turn the indigenous cultivator from his attitude of passive distrust towards untried agricul- tural methods and new products. Ground-nuts, tobacco (Havana and Virginia seed), wheat, Egyptian cotton, and potatoes are crops the introduction of which it is sedulously fostering ; but so far, except perhaps in the case of potatoes in the Shan States and ground-nuts in Magwe, the result of the experimental cultivation has not been altogether encouraging, for the operations are too often conducted half-heartedly by the villagers concerned. In time, some of the new products will no doubt gain a footing in the country. Agricultural shows are held annually throughout the Province at suitable centres. They are popular, but their usefulness, like that of experimental cultivation, has yet to be appraised at its full worth by the people. There are no model farms, but experimental gardens are maintained by Government at Taunggyi, Falam, Myitkyina, Katha, Sima, and Sinlumkaba in the Upper pro- vince. The position of private tenants is, generally speaking, good ; but measures are needed to improve their condition and to relieve them from indebtedness, and a Tenancy Bill, framed to secure these objects, is at present under consideration. Steps have been taken in Upper Burma to prevent the leasing of state land to persons other than bona fide agriculturists.

Small use is made of the Land Improvement Loans Act, 1883, in Burma, but loans under the Agriculturists' Loans Act, 1884, are common. During the years 1890-1900 the total of advances made under the latter enactment averaged about Rs. 41,000 per annum in Lower, and 2,13,000 in Upper Burma. Advances are made by Government, through the local ofificers, to deserving villagers on the security of the village head- man or of fellow villagers. The rate of interest demanded is 5 per cent, per annum, having been reduced to this figure from 6i per cent, in 1897-8, but a proposal to raise it again is under consideration. The present rate is far below the lowest interest that cultivators would have to pay on money borrowed from private individuals. The period for repayment is ordinarily two or three years. Money-lenders in Burma are sometimes recruited from the agricultural community itself. They are ordinarily either Chettis from Madras, whose rate is from if to 5 per cent, a month, or Burmans, whose demand is at times even more exorbitant. Thus in some Districts the Government loans are eagerly sought after, though in others the formalities that have to be gone through before the cash reaches the cultivator's hands and the rigid rules under which recoveries are effected often deter applicants from availing themselves of the loan rules. The popularity or otherwise of the advances depends to a large extent on the efforts made by the local ofificers to commend them to the agricultural community. Re- coveries are made without great difficulty ; and though occasionally it is found that applications have been made for other than bona fide agricultural purposes, this is the exception and not the rule. The total of irrecoverable sums is small. Steps have recently been taken to introduce the system of co-operative credit among the agriculturists of the Province. Under the provisions of the Co-operative Credit Societies Act (X of 1904) the people have been encouraged to start small societies, the members of which (usually from 30 to 50 in number) join together and subscribe a capital. Sums ranging from Rs. 1,000 to Rs. 4,000 are thus obtained, and to this Government adds a loan of a similar amount free of interest for the first three years and afterwards at 4 per cent. The combined amount is lent out among the members of the society at i per cent a month, and the profits go first to the for- mation of a reserve fund. When this has been built up, they will be devoted to bonuses to members. During the first four months of 1905 eight rural societies (four in Upper and four in Lower Burma) were established ; and at the end of May of that year they numbered 404 members, who had subscribed a capital of Rs. 12,160, to which Govern- ment had added Rs. 11,560 in the shape of a loan. The movement is at present in its infancy, but the progress so far has been encouraging.

Burmese cattle are of a type peculiar to Burma and other portions of Indo-China. Small, but sturdy and well set up, they are exceedingly docile and for their size possess considerable powers of endurance. Their hump and dewlap are less developed than in Indian beasts, and their horns are comparatively small. They are bred by the Burmans almost solely for draught purposes, and by the Shans for caravan traffic, not professedly for food nor ordinarily for dairy purposes, for the tenets of Buddhism proscribe the taking of life, and the use of milk and butter is only beginning to be recognized by the people of the country, in whose eyes to rob the calf of its natural food used to be almost aS reprehensible an act as to eat its mother's flesh. Religious scruples in this regard are being gradually broken down ; but the Burman's faith has left an indelible impression on the treatment of his cattle, which, except perhaps in Arakan, are infinitely better cared for than the sacred drudge of the average Hindu ryot. In some Districts a light-built breed of bullocks is used for cart-racing. Cattle are ordinarily driven out to graze early in the day and return to the villages at nightfall.

Some of the animals are housed under the dwellings of the villagers amid the piles on which they are erected, others are tethered in a shed close by the house. The diseases to which the cattle of the Province are most liable are rinderpest {kyaukpank), foot-and-mouth disease {shana kwana), anthrax {dautigthan or gyeikna), dysentery {thtve thun wun kya), and tuber- culosis (gyeik). Of these, the first claims the largest number of victims. Cattle-disease is kept under as far as possible by a staff of veterinary assistants whose duty it is to visit affected areas. Segregation is enforced. Outbreaks of infectious disease have to be reported to the civil authori- ties, and in Lower Burma all deaths of cattle are recorded and the death returns are collected by the police. In Rangoon full use is made of the provisions of the Glanders and Farcy Act of 1879. The price of cattle varies considerably. An ordinary pair of working bullocks may be purchased for sums varying from Rs. 120 to Rs. 150, but well-matched and powerful beasts will often fetch as much as Rs. 150 each. The price of cows ranges from Rs. 30 to Rs. 60. Buffaloes are used for ploughing and other draught-work, more so in the wet than in the dry Districts of the Province. For heavy and laborious work they are excellent and cost little to keep, for they subsist for the most part on what they find on the grazing-grounds. An ordinary pair of buffaloes may be purchased for from Rs. 150 to Rs. 200, though more is demanded for an exceptionally good pair.

The Burmese pony is small, its height ranging from 11 to 13 hands. It is very hardy and active, but hard-mouthed and often of uncertain temper. The so-called Pegu pony is well-known in India, but Major Evans, A.V.D., Superintendent of the Civil Veterinary department of Burma, throws doubt upon the theory that there was a separate Pegu breed. He wrote as follows in the Annual Report of the Provincial Civil Veterinary department for the year 1 899-1 900 : —

' Burma never, as far as I can ascertain, was a horse-breeding country. Certainly ponies, and some good ones, were bred in Lower Chindwin, Pakokku, Myingyan, and Shwebo, but even in Burmese times the supply was from the Shan States. We hear much of the so-called Pegu pony, as if a special breed of ponies existed in Pegu. There is not now, nor, so far as I can find out, ever was such an animal. The justly celebrated Pegu ponies were Shans, imported from the States, possibly via Shwegyin and Toungoo.'

The Shan States are still the main centre for pony-breeding in the Province, though good beasts are to this day bred in the Upper Burma Districts referred to by Major Evans. There is a small stud of Govern- ment stallions, but breeding operations have so far been attended by no great measure of success. The price of Burmese ponies varies, and has risen considerably during the past twenty years. The cost of a fair pony for ordinary purposes may be anything between Rs. 150 and Rs. 300. Racing ponies naturally command fancy prices.

Sheep and goats are bred to a small extent (mostly by natives of India), the former especially in the dry zone. A small breed of sheep is imported into Bhamo District from China. The average price of this Chinese variety is about Rs. 5. Indian sheep run to a somewhat larger figure, the maximum being sometimes as high as Rs. 12. The price of goats is about the same as that of sheep. Pigs are eaten freely by the Chins, Karens, and other hill tribes, and pig-breeding is carried on by Burmans as well as by Chinamen in certain localities. The price of pigs in Sagaing District, which may be looked upon as a typical pig-breeding area, ranges from Rs. 10 to Rs. 40 a head.

The area of uncultivated land in the Province is still so extensive that the provision of grazing-grounds has never been a matter of urgent importance ; and in the dry zone of Upper Burma, where there are enormous stretches of land too poor for cultivation but suitable for grazing, the question is never likely to be pressing. Care has, how- ever, been taken to provide for a future when cultivation may have spread to such an extent as to render the grazing problem a real one, and fodder reserves have been selected and demarcated. The matter is one to which special attention is directed when a District is being brought under settlement. Except in the dry zone, no special difficulties are encountered in providing food for cattle. In the dry Districts chopped millet stalks are largely used for fodder during the hot season, when vegetation is at its lowest ebb. In specially unfavoured tracts the water difficulty assumes serious proportions. In his Sunmiary Settlement Report (season 1899-1901) the Deputy-Commissioner of Myingyan wrote as follows : —

' In parts of Kyaukpadaung and Pagan during the hot months, when the tanks are dry and people fetch their water daily, often from a distance of 6 miles, the cattle fare very badly, and it is quite common to find them being herded 15 miles from water. At this time they are watered only every other day, and sometimes even only once in three days. The condition of the cattle at this time is terrible, and many die on the long road between fodder and water.'

This state of things is, however, fortunately the exception.

There are in Burma no regular fairs at which live-stock are collected for sale as in India. Opportunity is, however, occasionally taken of the gatherings at pagoda festivals and the like to do business in cattle or other animals. The annual festival at Bawgyo in the Hsipaw State, for instance, is usually made the occasion for a pony mart.

In Lower Burma, Prome and Thayetmyo Districts excepted, the heavy rainfall renders systematized irrigation operations unnecessary even for the culture of so exacting a crop as rice. The depth of water in the paddy-fields has to be carefully regulated, but an excess is with- out difficulty drained off through a temporary breach in one of the en- closing embankments, known as kazins ; and if at any time the empty- ing has been injudicious, and a field is momentarily in need of an extra supply of water, that supply will nearly always be available near at hand, and is admitted either by gravitation from an adjacent higher level or by lifting in a flat bamboo water-scoop. Thirsty crops, such as betel- vines, onions, durians, and oranges, are watered by hand.

In Upper Burma the case is widely different. In Myitkyina, Bhamo, and the other northern Districts, it is true, the climatic conditions differ but little from those obtaining in the north of Lower Burma ; but farther south it may be laid down as a general rule that, except in a few favoured tracts, rice cultivation can be carried on successfully only with the aid of a supply of water rendered available by artificial means and capable of being drawn upon at any time between seed-time and harvest. Other crops also need artificial watering, but it is only on behalf of rice cultivation that regular irrigation works are undertaken. The provision of a water-supply of the kind required has been recognized as a matter of vital interest in Upper Burma from time immemorial ; and among the legacies bequeathed to the British by the Burmese government in 1886 not the least important were a number of irrigation works, for the most part damaged or useless, but valuable, if for nothing else, for the lasting testimony they bore alike to the needs of the people and to the responsibilities of their rulers. Of these, the most ambitious were the Kyaukse and Minbu irrigation systems, the Meiktila Lake and the Nyaungyan-Minhla tanks, and the Mu and Shvvetachaung canals. In 1892 a Public Works Irrigation circle was formed in Upper Burma, not only to improve such of these larger systems as it was thought fit to preserve, but to put in order the host of minor village irrigation works that are scattered, in the shape of tanks and irrigation channels, through the greater part of the dry zone. The work undertaken has included projects for, and the construction of, new canals from loan funds, in addition to the remodelling, extension, and maintenance of old irriga- tion systems with funds provided from Provincial revenues.

The only completed work of the class known as 'major' is the Mandalav Canal, opened in 1902, which is 39 miles in length, cost about 51 lakhs, and is capable of irrigating 89,000 acres. It waters much the same country as a canal dug by the Burmans before annexation, which proved a failure owing to faulty alignment and the inability of the Burmans to deal with the severe cross-drainage from the Shan plateau. The Shwebo Canal, another ' major ' work which will benefit an even more extended area, is in course of construction \ and will probably cost about 52 lakhs. There was a Shwebo canal before annexation, but the new work does not follow the line of its predecessor, which, however, still performs useful functions. The construction of two canals, in connexion with the Mon river in Minbu District, has been started, and two more canals, the Ye-u and the Yenatha, are in contemplation ; when completed they too will be 'major' works. The great majority of the Government irrigation works in Upper Burma are, however, what are known as ' minor ' works. They are practically all adaptations of pre-existing native schemes, and for this reason only revenue accounts are maintained for them. They consist partly of canals, partly of tanks. The canals are mostly in Kyaukse, Mandalay, and Minbu Districts ; some of these are under the maintenance of the ordinary local officials, but the majority are kept up by the Irrigation department. The most important of the tanks main-

- This canal was opened in 1906.

tained by the department are the Kanna tank in Myingyan District, the Meiktila Lake and the Nyaungyan-Minhla tank in Meiktila District, and the Kyaukse tank in Yamethin District. Scattered over the dry zone are a considerable number of small village tanks, constructed locally, for the management of which the department does not hold itself respon- sible. No revenue is paid for water supplied from these small indigenous works. At the end of the year 1903-4 the total area irrigated by ' minor ' Government irrigation works amounted to 430 square miles.

Revenue, on account of water supplied from Government irrigation works, is levied in the shape of water rate, which varies in different localities, and which, on land cultivated with rice, ranges between R. i and Rs. 5-8 per acre. In settled Districts the water rate is included in the land revenue ; in unsettled Districts it is assessed separately and is levied only on non-state land irrigated from Government works. The total collections of separate water rate in 1903-4 amounted to Rs. 24,423. Government canals and tanks are ordinarily in charge of the Executive Engineer. The carrying out of urgent repairs to Govern- ment irrigation works constitutes a public duty which villagers in the vicinity of the works are liable to be called out to perform. A similar duty devolves upon the residents in the neighbourhood of the embank- ments which, in the delta Districts, have been built to protect low-lying areas from excessive inundation by the rivers.

Until quite recently no revenue had been obtained from the * major ' irrigation works of Upper Burma, but the Mandalay Canal has now begun to pay. Up to the end of 1 903-4 the total expenditure on works of this nature had amounted to 81 lakhs, of which 50 lakhs were in respect of the Mandalay and 30 lakhs in respect of the Shwebo Canal. No reliable irrigation finance figures are available for the first few years succeeding the annexation of the Upper province. During the ten years ending 1901 the average annual expenditure on 'minor' Govern- ment irrigation works of all kinds in Upper Burma was 9 lakhs, and the corresponding receipts amounted to 10-8 lakhs ; the average net profits for each year of the period in question may accordingly be taken at nearly if lakhs. In 1903-4 the expenditure on these ' minor 'irrigation works was 9-98 lakhs, and the gross receipts from the same 9-35 lakhs.

The only Government irrigation channel that is used for navigation is the Shwetachaung Canal in Mandalay District. On this tolls are levied on boats and timber.

In Lower Burma the only works having the same main agricultural objects as the irrigation works of the Upper province are the embank- ments in the delta of the Irrawaddy and Sittang, designed to guard the crops from the ill-effects of an overplus of water. In 1 900-1 the total area protected or benefited by these works was 925 square miles. The working expenses incurred in connexion with these works during the same year amounted to 3-4 lakhs, and the share of the land and other revenue credited to them was 13-56 lakhs, the net revenue thus amounting to iO'2 lakhs, which represents 75 per cent, of the gross receipts. In 1903-4 the corresponding figures of expenditure and revenue were 4'8 and i6-i lakhs respectively.

Tanks, wells, and canals are the ordinary indigenous means of irriga- tion in the Province. Water-wheels (jvV) are used here and there on the banks of rivers ; and there 'are other forms of water-lifts, of the trough, basket, or scoop type, known by different names, such as ku, kanwe, or maimglet. These latter are all worked by hand. A certain measure of engineering skill appears to have been devoted in Burmese times to the construction of canals. The village tanks already referred to are rough, very often consisting merely of a mass of earthwork thrown across the lower end of a well-defined catchment area ; but as a rule they are judiciously selected, and can often be converted with the help of a little trained engineering skill into suitable irrigation works. There are wells in nearly every village, but as a rule they supply water solely for drink- ing and washing. Such wells as are dug for agricultural purposes" are ordinarily found in the vicinity of betel-vine yards or fruit gardens. A rough well of ordinary depth can be dug for about Rs. 25. The cost of a pakkd or brick-lined well is a good deal higher, and ranges, according to the depth, between Rs. 150 and Rs. 500.

So far as can be ascertained, the aggregate area irrigable by exist- ing Government irrigation works of all kinds amounts to about 1,280 square miles.

The fisheries of Burma are important financially and otherwise. From time immemorial the exclusive right of fishing in certain classes . of inland waters has belonged to the Government,

and this right has been perpetuated in various fishery enactments, the latest of which is the Burma Fisheries Act of 1905. Fishing is also carried on along the coast, but the sea fisheries absorb but a small portion of the industry. Most of the fishermen labour in the streams and pools, which abound particularly in the delta Districts. The right to work these fisheries mentioned in the enactments alluded to above is usually sold at auction, and productive inland waters of this kind often fetch very considerable sums. River fishing is largely carried on by means of nets, and generally yields revenue in the shape of licence fees for each net or other fishing implement used. Here and there along the coast are turtle banks which yield a profit to Govern- ment. In the extreme south the waters of the Mergui Archipelago afford a rich harvest of fish and prawns, mother-of-pearl shells and their substitutes, green snails and trochas, shark-fins, fish-maws, and beche-de- mer. Pearling with diving apparatus was introduced by Australians with Filipino and Japanese divers in 1893. They worked mainly for the shell, it being impossible for them to keep an effective check on the divers as regards the pearls. After about five years, when the yield of shell had decreased, they all left. The industry is now carried on by natives.

[edit] Rents, wages, and prices

In Burma the prevailing form of land tenure is that known as ryot- xvdri. As a general rule the agriculturist is a peasant proprietor, who makes all payments in respect of the land he works directly to the state. Under native rule, with a few ^^*^^s, wages, prices.

exceptions, the origmal occupier oi all land in Lower

Burma obtained an almost absolute title to his holding subject to the payment of revenue ; but, though their early codes go to show that the people of the country originally possessed what at first sight would seem to be an allodial right of property in land, there is evidence to indicate that their interests were of a subordinate nature, and the fact that in certain circumstances abandonment of cultivation entitled the crown to claim a holding, proves that the ryot's tenure, while carrying with it the outward powers of a proprietor, was strictly limited in the interests of the state.

In Lower Burma the main principles of land tenure were continued unchanged after the country had become a British possession, and were not defined by special legislation until many years later. In Upper Burma, on the other hand, a different land policy was introduced when land revenue legislation was first undertaken, less than three years after the annexation of the province. The proprietary ownership of waste land, i.e. of land which had been hitherto unoccupied for the purposes of cultivation, or which had been so occupied and had subse- quently been abandoned, was held to be vested in the state ; and the Government asserted rights of ownership, inherited from the Burmese State, in islands and alluvial formations, in land previously termed royal land, and in land held under service tenures. Land coming within these categories formed a comparatively small proportion of the cultivated land of the province. Existing tenures remained, and still remain, undefined in respect of the greater part of cultivated land commonly called private land. Under both the Upper and the Lower Burma systems, however, the small peasant proprietor dealing direct with the state was the prominent figure in the revenue system, and it has thus come about that in Burma the relations between landlords and tenants have never assumed tlie prominence that they hold in zamin- dari Provinces. In 1881 tenants in Lower Burma were few in number; but in 1892 the Memorandum on the moral and material progress of the country during the preceding decade referred to the existence of a considerable and growing class of tenants in the Lower province, and gave an outline of this new trend of affairs : —

' This class is recruited mainly from persons who have formerly been landholders, have run into debt, and have in consequence had to part with the ownership of their holdings and occupy them as tenants. Many tenants, particularly in the delta of the Irrawaddy, are immigrants from Upper Burma and young men setting up house. Although a precise estimate cannot be made of the extent to which land is being, year after year, transferred from its original owners, it is certain that such transfers are now frequent in the neighbourhood of large trading centres, and that the area of land cultivated by persons in the condition of tenants, who have no statutory rights and pay rent to middlemen, is extensive and on the increase.'

In 1903-4 the total area let at full rents was 3,445 square miles. The same condition of things prevails, though to a less degree, in Upper Burma in connexion with bobabaingox non-state land. Full data regard- ing the area rented are not, however, available for the Upper province.

Rent is ordinarily paid in produce, taking the form of a proportion of the gross out-turn of the land leased. Cash rents exist, but at present they are the exception. In Lower Burma, in 1 899-1 900, only 3 per cent, of the total area rented was let at cash rents. It is somewhat dififi- cult to say what conditions precisely determine the rent paid by the actual cultivator to his immediate landlord. In Upper Burma disin- clination to move to a strange neighbourhood will frequently lead a stay-at-home cultivator to work land at a rent that leaves him the barest pittance to exist on ; while a husbandman, with more land than he can work himself, will often be content to make over the use of his more distant fields for an abnormally minute share of their produce, indeed sometimes for practically nothing, if he has any fear that a temporary abandonment of non-state land may lead to its classification as state land. Within these extremes practice is ordinarily regulated by a blind adherence to local custom, which has decreed what proportion of the produce is to be regarded as a fair and proper rent for each kind of crop on each class of soil. In Lower Burma rent is based more on practical considerations, but it is doubtful whether it bears as yet any close relation to what experience has shown to be the actual selling value of land of similar quality in the neighbourhood.

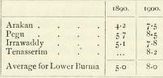

Custom in Upper Burma has decided that the amount of produce paid as rent shall be more or less regulated by the proportion of the cost of cultivation borne by the tenant. Tenancies have here been defined as of two kinds: simple, where the tenant bears the whole cost of cultivation ; and partnership, where the landlord contributes towards the expenses. Simple tenancies may be of different kinds. The rent may be fixed {asu- the or asu-pon-the tenancy), or it may be a share of the actual out-turn {asu-cha), or it may consist merely in the payment of Government dues. Of these the second is by far the commonest form. Partnership tenancy is known as osu-konpet. Partner landlords supply the seed-grain as a general rule, their further contributions to the cost of cultivation vary- ing in different localities. The rent ranges between one-half and one- tenth of the gross produce. Leases are ordinarily for a year only in Upper Burma ; in Lower Burma they are often for a longer period. The partnership tenancy system is not common in the Lower province. Rents have had an upward tendency for many years in Lower Burma. The average rent per acre in 1890 was equivalent to Rs. 5. By 1895 this average had risen to R.s. 6-7, and by 1900 to Rs. 8. The following figures show the average rents per acre, in rupees, in each of the Divisions of Lower Burma in i8go and 1900 : —

This represents the value of the produce rent on rice land converted

into cash at the current market rates. Upper Burma rent statistics are

incomplete, but it is clear that in parts of the Upper province rents are

by no means low. In Kyaukse they are distinctly high, and in the

Salin subdivision of Minbu the usual rent is half the gross produce.

Wages in Burma are high. Agricultural labour is less handsomely paid in the Upper than in the Lower portion of the Province, but even there wages are generally higher than in most places in India proper. Agricultural wages usually take the form of a small money payment in addition to food and lodging, and the total money value of the remuneration thus given seldom falls below Rs. 7 a month. An energetic able-bodied agricultural labourer can, in most of the Upper Burma Districts, reckon upon earning from Rs. 8 to Rs. 12 a month in money value. Cooly-work is paid for at a slightly higher rate than ordinary field-work. In Lower Burma field-labourers are paid during the field season at rates which not infrequently work out to an average of Rs. 15 a month for the whole year. Cooly-work proper is a feature only of the large industrial centres, and it is practically in the hands of natives of India, with whom Rs. 15 may be looked upon as a fair average monthly wage. Skilled labour is paid for at much the same rate in both portions of the Province. Domestic service is largely performed by natives of India ; and the facts that Burma is to Indians a foreign country, and that the general standard of wages and hiring is higher than in India proper, have succeeded in keeping servants' wages about 50 per cent, above the Indian level. Household servants are paid from Rs. 10 to Rs. 30 a mcjnth. The clerical wage may be said to commence at Rs. 25 a month. Its maximum is about the same as in India. Artisans' wages fluctuate between Rs. 15 and Rs. 25 a month; and mechanics of very ordinary attainments are able to make as much as Rs. 60, the better classes being capable of commanding even a higher figure.

Besides payment in the form of lodging and food, wages frequently take the form of remuneration in kind. For the whole nine months of the agricultural season in Lower Burma, the field-labourer usually receives 100 to 120 baskets of paddy; and a common payment for assisting in transplanting from the pyogin or nursery is a basket of paddy a day in addition to food, for so long as the job lasts.

Wages are regulated wholly by the demand for labour, and the lack of mobility displayed by non-agricultural labour in Burma is the reason for the difference in the wages prevailing in different portions of the Pro- vince. Scarcity, the extension of railways, and mining or factory opera- tions, have not as yet had any marked effect on the average wage.

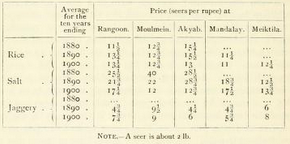

Rice is the staple food-grain of the country, and its price is affected by an almost endless variety of conditions. Speaking generally, and for the past twenty years, it has been quite exceptional for a rupee to purchase (retail) less than 10 or more than 20 seers of cleaned rice, the precise figure between these two extremes being determined in each District by the harvest, facilities of carriage, scarcity in India, internal disturbances, floods, revenue legislation, paddy rings, extension of cultivated area, and a host of other factors. The following table shows the average prices of rice, salt, and jaggery at important centres for the three decades ending with 1900 : —

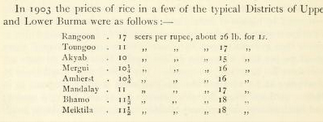

In 1903 the prices of rice in a few of the typical Districts of Upper and Lower Burma were as follows : —

Apart from yearly fluctuations, due mainly to variations in the cjuality of harvests, there has been a slight but steady downward tendency during the last twenty years in the purchasing power of the rupee in regard to rice, which, in view of the enormous increase in the demand for the staple for export purposes, is not surprising. The only other food-grain of any importance in Burma is millet. It is eaten regularly in the poorer portions of the dry zone, but in other localities only when the supply of rice is insufficient for the requirements of the people. Its price in 1903 in two typical dry zone Districts of Upper Burma was : — Mandalay . 29 seers per rupee, about 45 lb. for is. Meiklila . 2o| ,, „ „ 31 „

The material condition of the people is better in Lower Burma than in the Upper province, where deficient rainfall or the lack of culti- vable land in the vicinity of villages makes for a lower agricultural output and cuts down the profits of the husbandman. The financial advantages of the prosperous Lower Burma cultivator meet the eye less in his residence, household furniture, and ordinary dress than in his expenditure on food, ornaments, social ceremonies, and works of merit. There will be more silk waistcloths, anklets, and ear-plugs, more savoury accessories to the rice-bowl, and more festive gatherings in the rich farmer's house than in that of his poor neighbour; but the dweUing, and its fittings or lack of such, will be much the same in both cases, nor will any appreciable difference be noticeable between the outward circumstances of a villager cultivating his own land and of a landless day-labourer. The middle-class clerk, whose lines are for the most part cast in urban areas, will usually occupy a more pretentious building than the well-to-do agriculturist ; his furniture and his everyday attire will be more elaborate ; his jewellery will be more showy ; his food will be richer ; and his charities will be less. During the past twenty years the advance in the standard of comfort has been considerable among the town population.

An ordinary everyday costume of cotton jacket, cotton waistcloth, and silk gaungbaung or headkerchief costs from Rs. 3 to Rs. 5. A good jacket can be purchased for Rs. 1-8 and a cotton longyi or loin-cloth for Rs. 1-4. A single square of Japanese silk is enough for a head- cloth, and its price is R. i or even less, but for a full gaungbaung two squares are ordinarily required. Burmese shoes can be bought at between R. i and Rs. 1-8 a pair. Silk waistcloths are worn on special occasions. They cost from Rs. 10-8 upwards.

[edit] Forests

The forests of Burma may be conveniently classified as : I. Evergreen., comprising (i) httoral, (2) swamp, (3) tropical, (4) hill or temperate; and, II. Deciduous., comprising (i) open, (2) mixed, and (3) dry. The littoral forests are confined to Lower Burma, as are also, practically, the true swamp forests, while the dry deciduous forests mostly occur in the Upper province. The other classes are common to the whole of Burma. The mixed deciduous forests yield most of the out-turn of teak. Large areas covered entirely with teak are however not known, and it is rare even to find forests where teak is numerically the chief species. As a rule it is scattered throughout forests composed of the trees common to the locality. The in forests, so well-known on laterite formation, belong to the open deciduous sub-class, while evergreen hill or temperate forests clothe a large proportion of the uplands of the Shan States. A considerable forest area in Burma is covered with a luxuriant growth of bamboo.

The littoral and swamp forests contain little timber that is of any present value. In the tropical forests the kanyin {Dipte?-ocarpus turbi- 7iaius) and thitkado {Cedrela Toona) abound, while the thingan {Hopea odoratd) and the India-rubber tree {Fia/s e/astica), with oaks and pines, are typical of the evergreen hill forests. The mixed forests contain, besides teak and pyingado (Xylia do/abriformis), the pyinma {Lager- stroemia Flos Reginae) and the padank {Pterocarpus hidicus). In the dry deciduous forests the tree most utilized is perhaps the sha {Acacia Catec/iu), which furnishes the cutch of commerce.

The forest area of the Province may be classified under two heads : ' reserved ' forests, which are specially demarcated and protected, and whose produce remains entirely at the disposal of Government after satisfaction of the demands (if any) of right-holders ; and public forest lands, which are freely drawn on for trade and agricultural requirements. For the Reserves, which are responsible for the timber supply of the Province, working-plans are compiled so that a sustained maximum yield may be forthcoming in the future.

The area of the * reserved ' forests is increasing yearly as exploration of the forests proceeds, and time and staff are available for settlement duties. In i8Si the Reserves were 3,274 square miles in extent; in 1 90 1, 17,837 square miles. In the latter year the area of public forest land aggregated 81,562 square miles. No new Reserve is created until full inquiry has been made on the spot with regard to existing rights, domestic or agricultural ; and this formal recognition of prescriptive rights has done much towards rendering the people less antagonistic to the restrictions which it is sometimes necessary to impose for the welfare and maintenance of the forest. Areas once ' reserved ' may, should necessity arise, be disforested in the public interest ; and in times of scarcity of food or fodder the Reserves are placed at the free disposal of the people and their cattle.

For administrative purposes the timber trees of Burma may similarly be divided into two classes, ' reserved ' and ' unreserved.' The first includes teak, which is the property of Government wherever found, together with some eighteen other species to which this monopoly does not extend. The second class includes all other trees. ' Reserved ' trees can be cut only under a Government licence ; ' unreserved ' trees, on the other hand, may, outside Reserves, be utilized free of cost for the domestic and agricultural requirements of the people, but their produce is taxed when extracted for trade purposes.

Although the forests of Burma contain many valuable species of timber, some of which are largely used locally, teak is the only species in which an export trade of importance has yet been developed. The extraction of teak for trade purposes is carried out under the supervision of the Forest department, sometimes by means of Government agency, but chiefly by private firms under the sj'stem of purchase contracts. The annual yield in mature stems of a teak-bearing area is fixed for a term of years, and the given number of trees are annually girdled under the immediate control of a Forest officer. In the third year after girdling, when the timber has seasoned on the root, it is felled and logged. The logs are then dragged by buffaloes or elephants to the nearest floating stream, whence they ultimately reach deep water on one of the main rivers and proceed on their long journey to the seaports, where they are converted into beams and scantlings and shipped to the consumer. Years may thus elapse before a girdled tree comes on to the market, for its progress depends on the amount and frequency of the monsoon precipitations which cause the necessary flushes or freshes in the floating streams. In 188 1-2 the out-turn of teak from Govern- ment forests in Lower Burma was 31,246 tons, while the exports from the Province, including teak received from outside the limits of what was then British Burma, amounted to 133,751 tons. In 1892-3 the exports reached a total of 216,186 tons, valued at 164 lakhs of rupees, and ten years later a total of 229,571 tons, with a value of 203 lakhs, was recorded.

The value of minor forest produce, including bamboos, utilized for trade purposes in Burma, has as yet reached no considerable amount. It stood at 4| lakhs of rupees in 1903-4. It must, however, be remem- bered that the inhabitants of the country receive all their requirements in forest produce free of royalty, and that transport difficulties are as a rule so formidable in the Province that at present it is not found to be remunerative to extract for export any but the most valuable forest products.

The protection and improvement of the state forests in Burma is entrusted to the Forest department. Systematic operations for the settlement of forest areas, for their demarcation, survey, and protection from fire, involve the annual expenditure of very large sums. At the same time the extension of the forest area under the more valuable indigenous trees is not lost sight of. Taungya cultivation of teak is a speciality of Burma forest management, and consists in permitting shifting cultivation of cereal and other crops within Reserves, on the condition that teak seed is sown at the time of cultivation. The system is suitable to the requirements of the forest population, and has resulted in benefiting both the people and the forests. Plantations on an ex- perimental scale of exotic species such as rubber and eucalyptus, cS:c., are also receiving attention, the object being to prove, if possible, that such projects are remunerative and so to open out a field for the enrichment of the country by private enterprise.

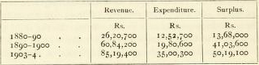

The following figures give the average annual financial results of forest management in Burma for the last two decennial periods ending with 1900, and also the figures for the year 1903-4 : —

The forest surplus may vary from year to year, being dependent chiefly on the amount of teak which reaches the seaports ; but the out-turn available in the forest is calculated on the anticipated demand controlled by the estimated annual growth of the trees.

The greater part of the as yet discovered mineral wealth of Burma lies in the upper portion of the Province. Petroleum is extracted in Arakan, and tin in Tavoy and Mergui Districts, but Mines and hardly anything in the shape of regular mining opera- tions is carried on in the rest of Lower Burma. The principal oil-bearing areas are in the dry zone of Upper Burma ; and gold, rubies, jade, amber, and coal have been discovered in paying quantities only north of the 22nd parallel of latitude.

Coal has been found in the Northern and Southern Shan States, notably near Lashio, not far from the Mandalay-Lashio railway, at Namniaw and in Lawksawk, as well as to the west of the Chindwin in the Upper Chindwin District, in Thayetmyo, in Mergui, and in Shwebo District. The Chindwin coal appears to be of the best quality yet found, and in the opinion of experts the coal area is fairly large and the supply likely to be considerable. Difficulties of communi- cation have, however, prevented the Chindwin fields from being worked, though it is probable that the existing obstacles will be surmounted in time. The only coal-mines which have been systematically w^orked are at Letkokpin near Kabwet in Shwebo District, which were started in 1 89 1, and taken over by a company in 1892. The coal has been used on Government launches, on the railway, and on the steamers of the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company. The out-turn in 1893 from the Kabwet or Letkokpin colliery was 9,938 tons. By 1896 it had risen to 22,983 tons, but it fell after this, and in 1903 was only 9,306 tons. The average number of hands employed in 1900 was 246. The coal was carried on a tramway from the mines to the river bank, and the average selling price was about Rs. 10 per ton. The mine has now, however, been shut down.

Iron is found in the Shan States, in Mergui, and elsewhere. It has nowhere, however, been systematically extracted and dealt with on European methods. Iron-smelting is a purely local village industry.

Gold is found in the beds of many of the streams of both Upper and Lower Burma, and the gold-washing of past generations has left its impress on the country in town and village names like Shwegyin, Shwedwin, and Shwedaung. It has been found in a non-alluvial form in Tavoy District ; in the Paunglaung Hills to the east of the Sittang ; in the Shan Hills, and in Katha District. The Kyaukpazat gold-mine in the last-mentioned District was worked for several years, but the lease has now been surrendered. In 1900 a prospecting licence was granted for gold-washing within the bed of the Irrawaddy, from the confluence above Myitkyina to the mouth of the Taping river in Bhamo District. That gold exists in paying quantities in Burma is indubitable. A good deal more money, however, is required for the successful exploitation of the metal than capitalists have as yet shown a disposition to invest. The gold-leaf used so largely for gilding pagodas in Burma comes for the most part from China.

Mogok is the head-quarters of the ruby-mining area of Upper Burma. The ruby mines are situated in the hills 60 miles east of the Irra- waddy, and about 90 miles north-north-east of the city of Mandalay. The stones are extracted partly by native miners and partly by the Burma Ruby Mines Company. The first lease to the company, granted by the Government in 1889, was for the extraction of stones by European methods, and for the levy of a royalty from persons working by native methods, and provided for the payment of a share of the company's profits to the Government. It expired in 1896, and was then renewed for a further term of fourteen years at a rent of Rs. 3,15,000 a year plus a share of the profits, the royalty system being continued. In 1899 a debt due by the company to the Government was written off and the annual rent reduced to 2 lakhs, while the Government share of profits was increased. By a lease running for twenty-eight years from April 30, 1904, the rent has been fixed at 2 lakhs, with 30 per cent, of the net profits. The system of extraction adopted is to raise the byo72 or ruby earth (found ordinarily some 20 feet below the surface) from open quarries, and to wash it by machinery similar to that employed in the South African diamond mines. The stones thus obtained are then sorted and the spinels are separated from the rubies.

The capital of the Ruby Mines Company stands at present at £180,000. The company's establishment was in 1904 approximately 1,600 strong. Of this staff 44 members were Europeans and Eurasians, the rest natives of India, Shans, Chinese, Maingthas, and Burmans. Rubies are found in the Nanyaseik tract, in the Mogaung township of Myitkyina District, and in the Sagyin tract of Mandalay District, but neither of these areas approaches the Mogok ruby tract in point of productiveness. The Nanyaseik tract is now practically deserted.

The richest oil-bearing tract of Burma lies in the valley of the Irrawaddy, in the southern portion of the dry zone of the Upper province, at about the 21st parallel of latitude. It has been worked by the natives certainly since the middle of the eighteenth century, but modern boring appliances were not introduced till 1889. The three principal centres of the petroleum-extracting industry are Yenangyaung in Magwe District and Singu in Myingyan District on the eastern bank of the Irrawaddy, and Yenangyat in Pakokku District on its western bank. The oil is obtained partly from wells dug by native labour, but mainly by a system of regular boring carried on by the Burma Oil Company, which purchases the bulk of the oil obtained by the native workers (tivinzas), and pays a royalty to Government of 8 annas per 100 viss (365 lb.) in the case of the older leases and per 40 gallons in the case of the later ones. From the wells the crude oil is conveyed by pipes to tanks on the river bank, where it is pumped into specially constructed flats or floating tanks which are towed by the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company's steamers to Rangoon. Here it is refined in the Oil Company's works at Syriam and Danidaw. In 1903 the value of the Yenangyaung oil extracted was 36-4 lakhs, and of the Yenangyat oil 15 lakhs. The royalty on the output of petroleum was 4^ lakhs in 1 90 1 and 8 lakhs in 1903. The Burma Oil Company has a staff of over 7,000 employes, of whom about 150 are Europeans and Americans. The Rangoon Oil Company works also at Yenangyat and Singu, and oil is won by the Burma Oil Company from the Minbu Oil Company's concessions. Petroleum is also worked in the Akyab and Kyaukpyu Districts of the Arakan Division, but the Arakan fields are not to be compared with those of the dry zone for richness. The total production of kerosene oil in Burma has risen f-om about 10 million gallons in 1893 to 83 million gallons in 1903.

Hitherto jade has been found in paying quantities only in the Myit- kyina District of Upper Burma. It is quarried in the hills during the dry months of the year by Kachins, and is purchased on the spot by Chinese traders, and by them transported in bulk by water and rail, for the most part to Mandalay, where the blocks are cut up. The purchase of the jade in bulk is a highly speculative transaction, as, till it has been sawn up, it is almost impossible to say how much marketable green jade a particular block may contain. Practically all the jade extracted finds its way eventually into China. The right to collect the ad valorem royalty of ■Ty2)\ per cent, on jade-stone is farmed out by Government. In 1 89 1 this right fetched Rs. 55,500. It was then sold annually, but a falling off in the amount paid rendered it advisable to extend the period of letting to three years. In 1899 the triennial lease fetched Rs. 60,350. The industry is not likely to pass out of native hands unless a fresh jade-bearing area is discovered.

Mergui District, in the extreme south of Burma, produces annually about 60 tons of smelted tin, and the neighbouring District of Tavoy about a ton. The methods employed are exclusively Chinese, but three European firms hold concessions. The industry has been carried on for thirty years without great success, and it has been said that much of the tin ore is of very low grade. The chief difficulties are the want of communications, and the fact that the tin-bearing tracts are everywhere covered with dense forest, which make their examination a work of much labour and expense.

The mines from which the amber of Burma is dug are situated beyond the administrative border of Myitkyina District in the extreme north of the Province, where mining operations are conducted on a very small and primitive scale by the natives of the locality. It is possible that in former times the amber area was more productive than it is at the present day.

The production of salt is a purely local industry. Salt is obtained in small quantities by boiling along the sea-coast, as well as here and there in nearly all the Districts of the dry zone of Upper Burma ; but as a rule it is bitter and of poor quality, and is unable to compete with the imported article. The local output of salt in 1900 was estimated at 415,000 cwt. For 1902-3 the estimate was fixed somewhat lower, for a modification in the system of levying duty resulted in the temporary closing of some factories, but 1903-4 showed a rise to 517,000 cwt.

Silver and lead occur in the Myelat division of the Southern Shan States, in the State of Tawngpeng in the Northern Shan States, and in the Mergui Archipelago ; but their extraction has never assumed large dimensions. Alabaster, steatite, mica, copper, and plumbago, the last of poor quality, are also obtained in small quantities in portions of the Province.

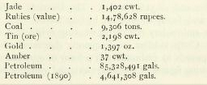

The following is the out-turn of the principal minerals of Burma in the year 1903 : —

Of domestic industries cotton-weaving is the most important and widespread. In 1901 the number of persons supported by cotton- weaving by hand was returned as 189,718, of Arts and whom the actual workers numbered 9,392 males and 136,628 females. This latter figure represents a fraction only of the total of women and girls actually engaged in cotton-weaving, for the great majority of those who wove solely for home consumption must have returned weaving, if at all, as a subsidiary occupation. The loom is a feature of nearly every house in certain localities ; and in the past, before imported cloth began to compete with home-spun, its use must have been far more widespread than now. As it is, the foreign is slowly ousting the home-made article, and where home-weaving is still fairly universal more and more use is made of imported ready-dyed yarn. In fact, it is only in the cotton-growing areas of the dry zone that local thread is used in any quantities. There are no cotton-mills in Burma. Everything is woven on hand- looms.

Silk-weaving is a purely professional industry, though, like cotton- weaving, it is wholly the product of hand labour. The silk cloth woven is for sale, not, except in rare cases, for home consumption. The prospects of the silk-weaving industry have been damaged by the advent of cheap Manchester and Japanese silk goods, and the number of weavers in Sagaing and Mandalay, the head-quarters of the industry, has declined enormously of late years ; but Burmese silk, where not woven of silk thread prepared and dyed in Europe, is still, by virtue of its texture and durability, able largely to hold its own. The Burmese silk is woven from Chinese silk thread, purchased raw and treated and dyed locally ; but its comparatively sober hues fail to appeal to the average Burman as do the brilliant acheik and other cloths made of the gaudy silk thread of commerce. Silk is the attire of the well-to-do ; and all but the very indigent, even when they ordinarily wear a cotton waist- cloth, have a silk paso (waistcloth) or tamein (petticoat) stored up for gala days. The head-gear of the people is almost invariably of silk. The locally made silk is too stiff for the gaungbaungs or headkerchiefs of the men, and for this purpose custom has pronounced in favour of the flimsy Manchester or Japanese squares that are obtainable in all the bazars of the country. The total number of persons supported by silk- weaving in 1 901 was 34,o;29, of whom the actual workers numbered 5,973 males and 18,316 females. The Districts of Prome, Mandalay, Kyaukse, and Tavoy showed the highest totals.