Brahmin/ Brahman (home page)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Indpaedia pages about Brahmins/ Brahmans

The following is a partial list of the pages that Indpaedia has about the Brahmin/ Brahman community. More Brahmin sub-castes can be found through the Search button (top right).

In case we have left out any sub-caste or any detail about the sub-castes already included on Indpaedia, such information may please be sent as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Agni-brahman <>

Bara-Brahman <>

Brahma Kalpit Brahman <>

Brahman, Babhan <>

Brahman: Ahivasi <>

Brahman: Ajagyak <>

Brahman: Bengal<>

Brahman: 'Central Provinces' <>

Brahman: Chakuua <>

Brahman: Deccan<>

Brahman: Dogamia <>

Brahman: Gaur <>

Brahman: Holaya <>

Brahman: Jadua- Jaduah <>

Brahman: Jharua <>

Brahman: Jijhotia <>

Brahman: Kanaujia, Kanyakubja <>

Brahman: Khedawal <>

Brahman: Magllaya <>

Brahman: Maharashtra, Maratha <>

Brahman: Maithil <>

Brahman: Maithiu <>

Brahman: Malwi <>

Brahman: Mastan <>

Brahman: Mohyal <>

Brahman: Nagar <>

Brahman: Naramdeo <>

Brahman: Punjab <>

Brahman: Raghunathia <>

Brahman: Sakaldwipi <>

Brahman: Sanadhya, Sanaurhia <>

Brahman: Sarayuparia <>

Brahman: Sarua <>

Brahman: Sarwaria <>

Brahman: South India <>

Brahman: Utkal <>

Brahman-Andhra: Deccan <>

Brahman-Golak: Deccan <>

Brahman-Kanada,Brahman-Karnatic: Deccan <>

Brahman-Karhadas: Deccan <>

Brahman-Kasta: Deccan <>

Brahman-Kokanastha: Deccan <>

Brahman-Malvi: Deccan <>

Brahman-Pannase: Deccan <>

Brahman-Vidu: Deccan <>

Hussaini Brahmin/ Dutt <>

Marwadi Maha Brahman: Deccan <>

Marwadi-Brahman Sonar: Deccan <>

Brahmin: Tamil<>

Brahman surnames, titles

(From People of India/ National Series Volume VIII. Readers who wish to share additional information/ photographs may please send them as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.)

Synonyms: Sasani [Orissa]

Groups/subgroups: Acharya, Agradani, Baidik, Barendra, Madhya Sreni, Morapora Agradani Patit, Rarhi, Saptasati, Vaidik [West Bengal]

Patro [Orissa]

Chakravarti, Chowdhuri, Ghatak, Roy, Roychowdhury [West Bengal] Aiyar, Bhatt, Desh Pande, Joshi, Mishra, Nagar, Nambudari, Ojha,

II76

Communities, Segments, Synonyms, Surnames and Titles

Pandey, Rao, Tripathi, Upadhyay [Andaman & Nicobar Islands]

Aradhya, Bhandari, Kini, Mallan, Pai, Shenai, Vadhyar [E. Thurston]

Achari, Adhikari, Agasti, Agnihotri, Ahitagni, Avasthi, Bagchi, Baguli, Bahriyar, Bajapeyi, Bakriyar, Bakshi (honorary),

Baral, Bargwal, Bharial, Chattopadhyaya [H.H. Risley]

Pandit [M. Montgomery]

Agnihotri, Chaube, Dikshit, Dube, Pande, Sukul, Tiwari, Upadhya [Russell & Hiralal]

Surnames: Agnihotri, Bhojlei, Bujroo, Chaturvedi, Dwivedi, Gaur, Joshi, Jyotishi, Nagarkoria, Pandit, Purohit, Saraswat, Sharma, Tripathi [Himachal Pradesh]

Acharya, Das, Devta, Dibedi, Doia, Hota, Kara, Layak, Mahanti, Misra, Nanda, Nasauk, Padahar, Panda, Pani, Panigrahi, Pari, Patra, Ratha, Sanapati, Sarangi, Satpali [Orissa]

Bagchi, Bandyopadhyay, Batabyal, Bhattacharya, Chakravarti, Chattaraj, Chattopadhyay, Gangopadhyay, Ghatak, Goswami, Haider, Lahiri, Laskar, Maitra, Mazumdar, Mukhopadhyay, Roychowdhuri, Sanyal [West Bengal]

- Exogamous sections: Agastya, Angirasa, Atri, Bharadwaj, Bhargava, Bhrigu, Garg, Gautam, Jamadagni, Kashyap,

Kaushik, Marichi, Pulastya, Vasishtha, Pulaha, Sandilya, Vasishtha, Vatsya, Visvamitra [Russell & Hiralal]

Akas, Akshagrami, Ambuli, Andarie Nehra, Andarie Pirapur, Annasani, Anraiwar Usrauli, Anraiwar Anrai, Anraiwar Anraiwar Jhaua, Arath, Asrukoti, Aturthi, Babhaniame Babhaniame Katma, Bagchhi, Baguri, Bahal, Bahirarwar,

Bahirarwar (punach) Bala, Balayashthi, Bali, Balihari, Balthubi, Bandya (Kulin), Bapuli, Baral, Bhagai, Bhatta,

Chatta, Chautkhandi Dayi, Dighal, Dingsai, Dirghati, Ganguli (Sabarna gotra), Gargari, Ghanteswari, Ghoshal, Ghoshal Simlai, Gur, Uar, Kanjiari, Kanjilal, Karrain, Kaujilal, Kesarkuni, Kulabhi, Kundalal Mahinta, Mukhaiti, Mul,

Nanidbali, Nayari, Parhat, Parhial, Parial, Patitunda, Pippalai, Pitamundi, Pungsika, Purbba, Pushali, Puritunda, Rayi (Gauna Kulin), Saharik, Sateswari, Siarik Siddhal [H.H. Risley]

Bharadwaj, Goutam, Parasar, Sandilya, Savarna, Vatsa [West Bengal]

Agastya, Agnibesma, Angirasa, Atri, Bachn, Basishtha, Batsa, Bharadwaja, Kasyapa, Sabarna, Sandilya [H.H. Risley] Atri, Badarayana, Bharadwaj, Bhargav, Garg, Gautam, Goutam, Harita, Jamadagni, Kapila, Kashyap, Katyayana, Kaushik, Koundinya, Naidhrava, Parasar, Parthiva, Rouhila, Sandilya, Sankhayana, Upamanya, Upamanyu, Vainya, Vardhriaswa, Vasisht, Vatsa, Veethahavya, Vishwamitra [S.S. Hassan]

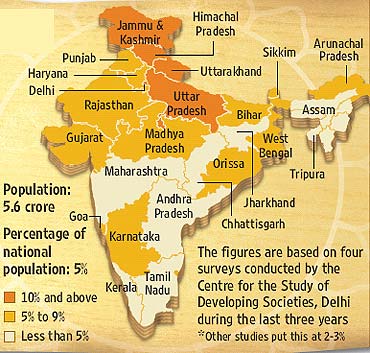

Population

2004-07: a demographic profile

Brahmins In India, 4 JUNE 2007: Outlook

Snapshot of a community: population per state - the rich, the poor and the educated...

Snapshots

Total Population: 5.6 crore

Poor Brahmins: 13%

Rich: 19%

Literacy levels above the age of 18: 84%

Graduates: 39%

Brahmin chief justices between 1950 to 2000: 47%

Associate justices between 1950-2000: 40%

State Percentages

From: Brahmins In India, 4 JUNE 2007: Outlook

From: Brahmins In India, 4 JUNE 2007: Outlook

See graphics:

The Brahmin population- State Percentages

The Brahmin population- state-wise

Down in the Cow-belt

Falling percentage of Brahmin MPs elected in the Hindi belt

1984: 19.91%

1989: 12.44%

1998: 12.44%

1999: 11.3%

2007: The present Lok Sabha has only 50 Brahmin MPs nationwide. That’s 9.17 per cent of the total strength of the House.

Today’s Brahmin Politicians

From: Brahmins In India, 4 JUNE 2007: Outlook

See graphic:

Brahmin Politicians, as in 2007

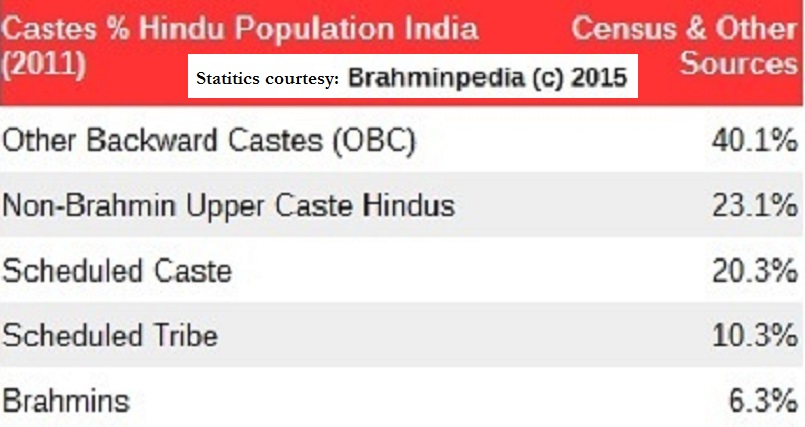

A 2011 estimate

The census could not have yielded this information readily. It must have either been extracted from the Census. Or taken from ‘other sources.’

See graphic: The Brahmin (and other) Hindu population of India, 2011, as estimated by the Brahminpedia.

The census could not have yielded this information readily. It must have either been extracted from the Census. Or taken from ‘other sources.’

Divisions-- and history

This section (which includes all materials up to and including Brahmins taking up other duties) is an extract from a much longer and much more detailed article posted on

from which readers will find far greater information on the subject.

Brahmin (Brāhmaṇa, ब्राह्मणः) is the class of educators, law makers, scholars and preachers of Dharma in Hinduism. It is said to occupy the highest position among the four varnas of Hinduism.

The English word brahmin is an anglicised form of the Sanskrit word Brāhmana (Brāhman also refers to a mystical concept in Hinduism). Brahmins are also called Vipra "inspired",or Dvija "twice-born".

It is a misconception that brahmins are only priests. Only a subsect of brahmins were involved in the priestly duties.

They also took up various other professions since late vedic ages like doctors, warriors, writers, poets, land owners, ministers, etc. Some parts of India were also ruled by Brahmin Kings.

History

The history of the Brahmin community in India begins with the Vedic religion of early Hinduism, now often referred to by Hindus as Sanatana Dharma. The Vedas are the primary source of knowledge for brahmin practices. Most sampradayas of Brahmins take inspiration from the Vedas. According to orthodox Hindu tradition, the Vedas are apauruṣeya and anādi (beginning-less), but are revealed truths of eternal validity. The Vedas are considered Śruti (that which is heard) and are the paramount source of Brahmin traditions. Shruti includes not only the four Vedas (the Rigveda, the Yajurveda, the Samaveda and the Atharvaveda), but also their respective Brahmanas, Aranyakas and Upanishads.

Brahman and Brahmin (brahman, brahmán, masculine) are not the same. Brahman (bráhman, neuter), since the Upanishads, refers to the Supreme Self. Brahmin or Brahmana (brahmán, brāhmaṇa) refers to an individual. Additionally, the word Brahma (brahmā, masculine) refers to first of the gods

Brahmin migration

Devdutt Pattanaik, Dec 31, 2022: The Times of India

To appreciate the history of Africa, we have to study the history of its many tribes. To appreciate the history of India we have to study its many castes. Not the caste system. Just castes – what foods were prepared by different endogamous groups, what kind of clothes they wore, what vocations they followed, where they migrated, who they worshipped, what language they spoke.

However, academicians shy away from studying castes as they will be seen as casteist. Politicians and activists allow only condemnation of caste, and mock all enquiry into caste. This prevents us from understanding Indian culture in its totality.

Brahmin migration

Let's take the example of the Brahmins. The assumption is Brahmins have existed in every corner of India for thousands and thousands of years. But this is not true.

TheRig Veda talks of a geography that is restricted to the Punjab-Haryana region, with more references to the rivers near the Indus Valley and very few references to the rivers in the Gangetic plains.

However, later Vedic literature, such as Brahmana and Upanishad , speaks of the spread of Vedic culture along what is today called Uttar Pradesh and towards what is now called Bihar, which means as Vedic culture spread, Brahmin communities started emerging in the Gangetic plains around 3,500 years ago.

How then did these Brahmins reach Kerala? When did they reach Kerala? If we study local legends, we are told that it is Parshuram who brought Brahmins to Kerala. This legend is not more than 300 years old.

As per historical inscriptions and copper plates that speak of land grants to Brahmin communities, we know the Brahmin migration to Kerala happened around the eighth century AD, so 1200 years ago. Not before. The idea of Brahmins migrating is known in Mahabharata and Ramayana , but it is not part of the imagination.

The epics speak of rishis (sage, saints) travelling to different parts of India. We hear of Dirghatama whose children become kings of Bengal and Odisha and Assam. Jamadagni, Gautama, Atri and Agastya are associated with the Narmada, Godavari, Krishna and Kaveri river basins. In stories, these Brahmins often marry daughters of local kings. They are, thus, related to the royal family and receive royal favours. They become what Brihaspati is to Devas and Shukra is to Asuras. North to south Historical documentation emerges with literature like Kalhana’s Rajatarangini written in 12th century Kashmir, which talks about Pancha Gauda Brahmins, referring to North-Indian Brahmins, and Pancha Dravida Brahmins. The Pancha Gauda Brahmins are Saraswat (Kashmir, Punjab), Kanyakubja (Gangetic), Gauda, Utakala (Odisha) and Mithila (Bihar). The Pancha Dravida are Gurjara (includes Rajasthan), Maharashtrika, Karnataka, Tailanga, and Dravida (for Tamil and Kerala).

According to the oldest census conducted in 1931, Brahmins accounted for about 4% of the entire population, with maximum numbers in Uttar Pradesh –12% – even more in the hilly regions of Uttaranchal, where Brahmins took refuge after the Islamic invasion of the 12th century. Nepal was another place where many Brahmins took shelter.

These Brahmins who served courts even took Hindu ideas to Vietnam, Cambodia, and Java from the 3rd century onwards. This stopped after sea travel was banned in the Dharma-shastra, which declared that sea travel leads to 'loss of caste', from around 12th century CE.

In Kerala and Tamil Nadu, the minority Brahmins controlled maximum land directly and indirectly via temples. The practice of giving land to temples and to Brahmins is recorded from around the 3rd century AD. These lands were called Deva-bhoga and Brahmadeya.

In Kerala, only the eldest son could inherit Brahmin lands, and so younger sons had to seek employment elsewhere. They hoped to be son-in-laws in affluent non-Brahmin families. Kerala folklore is full of tales that inform us how children of Brahmin fathers are brilliant, no matter who the mother is, and no matter which family they are raised in. Parayi Petta Panthirukulam, a collection of stories, tells us how Vararuchi begets many children with his 'low' caste wife but asks her to abandon them. They are raised by different caste groups and each one turns out to be a genius.

We know that kings of India invited Brahmins from other parts of India when they did not get support from local kings. In the Vijaynagar Empire, and much of South India, there was great rivalry between Smarta Brahmins and Sri Vaishanava Brahmins.

There were many sects that were fiercely territorial in ritual, political and economic matters. Sena kings invited Kanyakubja Brahmins, which gave rise to the Kulin Brahmin system. As late as the 17th century, Chatrapati Shiva ji Maharaj invited Vedic Brahmins from Banaras to perform his coronation ceremony as many local Brahmins were hostile to this idea.

So the history of Brahmins will talk about migration from the north to the south to different parts of India. Brahmin and Vedic culture did not emerge from the earth; it came with migrants from the Gangetic plains.

Varied occupations

While traditionally Brahmins moved out of Muslim territory, certain Muslim kings encouraged Brahmin bureaucrats – and we see that in Kashmir. The number of Brahmin bureaucrats also increased in some of the Mughal courts. This happened in places where Muslim kings did not trust Muslim courtiers, and wanted a non-Muslim buffer zone in the court between the throne and the people.

Brahmins often faced competition from Kayastha communities who were traditional non-Brahmin bookkeepers. This rivalry continues even today in political circles, most evident in state politics of Odisha and Maharashtra.

We must not forget that the Peshwas who were also Brahmins – which means the Brahmins took up arms and became rulers in later periods. These Brahmins claimed to have been ‘created’ by Parashuram just justifying their role as de-facto rulers.

The idea of the soldier-Brahmin became popular in the 17th century. In Odisha, images of the armed Nagarjuna are supposed to represent legendary Parashurama as well as historical warrior-ascetics inspired by Adi Shankara, who defend pilgrim sites from Muslim hordes. Mangal Pandey of 1857 fame was a Brahmin soldier in the East India Company’s army, revealing how Brahmins were taking up new occupations as not all Brahmins had access to education and jobs in the bureaucracy.

While some Brahmins served as temple priests, many were landowners, others were experts (shastri) in astrology, administration, legal and financial matters, which enabled them to work as courtiers in royal courts and as clerks with traders.

Many weavers and musicians identify themselves as Brahmins but are considered ‘lower’ Brahmins compared to the ‘higher’ educated Brahmins in the Vedas and Shastras. These communities were given Brahmin status in order to access the temple.

As many tribal priests were incorporated into Hindu fold, they too were made ‘lower’ Brahmins as we find in temples of Jagannath, in Odisha. There are folktales of their daughters marrying local Brahmin migrants. Brahmins who performed funeral rituals were called ‘lower’ Brahmins. Thus, there was an internal hierarchy between Brahmins. In Dharma-shastra , the temple priest was lower than the Brahmin who performed fire-rituals and knew the Vedas.

All this reveals the diversity of the Brahmin community on historical, geographical and vocational grounds. Imagine what more diversity exists in other communities and caste-categories (varna) of India.

Are Brahmins a single homogenous group?

Devdutt Pattanaik, May 22, 2021: The Times of India

Hinduism prefers two-way conversations over one-way instructions from the powerful to the powerless

Buddhism speaks of the discourses given by the Buddha to thousands of monks, nuns and lay people at Jetavana. Jainism speaks of samavasaran, when the Tirthankara reveals Jain wisdom to all creatures, earthly and heavenly, who sit around him in a circle. Jewish folk speak of Moses speaking from atop Mount Sinai. Christians speak of Jesus delivering the sermon on the mount. Muslims speak of Muhammad giving his final farewell sermon after his first Haj pilgrimage after the conquest of Mecca. But Hindus? Do Hindu gurus give sermons? Yes, in the 21st century. Following the Buddhist and Christian model, Hindu sermons on Advaita philosophy are popular, as attempts are made to homogenise Hinduism. But does Vishnu give a sermon? Does Shiva, or Ganesha, give a sermon? Is sermon a theme in the Puranas?

In Tamil temple art, we find images of Shiva as Dakshinamurti, seated atop a hill, under a banyan tree, facing the south, and giving lectures decoding the Vedas and Tantras. Shiva’s ‘south-facing’ discourse is not a sermon on how to live life, but a commentary that transforms mysterious Veda (Nigama) into tangible accessible Tantra (Agama). We are told all sages travel north to hear him speak; to restore balance to the world, Shiva tells Agastya to travel south. This story grants legitimacy to Agastya-muni, the legendary sage who spread Vedic ideas to the south. No such sermon is given by pre-Agastyan gods of Tamil literature: Ceyon (Murugan), Mayon (Krishna/Vishnu), Vendon (Indra), Kadalon (Varuna) and Kotravai (Durga), who are linked to different landscapes (mountains, forests, fields, seashores, and dry lands) and different moods of love (union, waiting, quarrelling, pining, and anxiety).

Gurus like Matsyendranath and Gorakhnath do not give sermons, though they travel around with hundreds of their disciples, shouting ‘Alakh Niranjan’ (salutations to the formless god), performing austerities and magic, helping and humbling people in the countryside. The Puranas refer to a gathering of rishis in Naimisha woods on the banks of the river Gomti, where they listen to stories of gods and goddesses through which Vedic wisdom is communicated. Stories, not sermons. Amar Chitra Katha and televisions serials have created the image of a rishi talking under a tree with students listening to him, in hermitages. But that is Brahmin children chanting the Vedic hymns by rote, without actually bothering to analyse it. No sermonising there either. Just memorising.

Hindu gods do not have messages for humanity. By contrast, the Christian God Yahweh has prophets, and Allah, in Islam, has 1,24,000 messengers (paigambar) communicating over human history. Religion is about following the message. Hinduism is not a religion as there is no ‘message from God’ or ‘sermon of Ram’ or ‘sermon of Krishna’. Modern, 21st century gurus do tend to make the Bhagavad Gita a sermon; but it is a private conversation between a warrior in crisis (Arjuna) and his wise charioteer (Krishna). It is not a message for humanity -- unless we assume all humans are in crisis wondering on the ethics of killing relatives for property.

In art, we often see Ram and Sita talking to Hanuman, and decoding the Vedas for him, as Shiva did for the siddha-rishis. The decoding is often private. We hear stories of how Shiva wants to decode the Vedas for Parvati in private but is overheard by fish, serpents and birds who are then cursed. They turn into sages: The fish-sage Matsyendrath, the snake-sage Naganath or Karkotaka, and the bird-sage, or Kakabhusandi. They share fragments of divine wisdom with humanity. These are the Upanishads, conversations between two people, like Janaka and Ashtavakra. These are two-way conversations between equals, not a one-way communication from the powerful to the powerless. The Hindu gods never do a ‘mann ki baat’.

In Hinduism, the divine is within (jiva-atma) and can germinate to appreciate the truth of the world and life (param-atma). Conversations about people sharing (sam-vaad) different experiences of truth, thus expanding our mind with new ideas and thoughts. It’s not about getting people to align to one single way. For the divine seed germinates differently in different contexts, takes different paths, like no two trees have the same branches or roots. This appreciation of diversity, and uniqueness of every individual, is at the heart of Hinduism. There is no tribe in the spiritual realm. All people are not the same, and no one is a passive powerless recipient. There is no room for monologues, or sermons. Only dialogues, as in a good relationship. Give and receive, as in a yagna.

Devdutt Pattanaik writes a fortnightly column that filters the voices on all sides

(Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the author's own)

Brahmin communities

The Brahmin castes may be broadly divided into two regional groups: Pancha-Gauda Brahmins from Northern India and considered as Aryans and Pancha-Dravida Brahmins from Southern India considered as Dravidian as per the shloka, however this sloka is from Rajatarangini of Kalhana which is composed only in 11th CE and many communities find their traces from sages mentioned in, much older Vedas and puranas.

कर्णाटकाश्च तैलंगा द्राविडा महाराष्ट्रकाः,

गुर्जराश्चेति पञ्चैव द्राविडा विन्ध्यदक्षिणे ||

सारस्वताः कान्यकुब्जा गौडा उत्कलमैथिलाः,

पन्चगौडा इति ख्याता विन्ध्स्योत्तरवासि ||

Translation: Karnataka (Kannada), Telugu (Andhra), Dravida (Tamil and Kerala), Maharashtra and Gujarat are Five Southern (Panch Dravida). Saraswata, Kanyakubja, Gauda, Utkala (Orissa), Maithili are Five Northern (Pancha Gauda). This classification occurs in Rajatarangini of Kalhana and is mentioned by Jogendra Nath Bhattacharya in "Hindu Castes and Sects."

Panch Gaud Brahmins

Panch Gaur (the five classes of Northern India): (1) Saraswat, (2) Kanyakubja, (3) Maithil Brahmins, (4) Gauda brahmins (including Sanadhyas), and (5)Utkala Brahmins . In addition, for the purpose of giving an account of Northern Brahmins each of the provinces must be considered separately, such as, Kashmir, Nepal, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Kurukshetra, Rajputana, Uttar Pradesh, Ayodhya (Oudh), Gandhar, Punjab, North Western Provinces and Pakistan, Sindh, Central India, Trihoot, Bihar, Orissa, Bengal, Assam, etc. The originate from south of the (now-extinct) Saraswati River.

In Bihar, majority of Brahmins are Kanyakubja Brahmins, Bhumihar Brahmins and Maithil Brahmins with a significant population of Sakaldiwiya or Shakdwipi Brahmins. With the decline of Mughal Empire, in the area of south of Avadh, in the fertile rive-rain rice growing areas of Benares, Gorakhpur, Deoria, Ghazipur, Ballia and Bihar and on the fringes of Bengal, it was the 'military' or Bhumihar Brahmins who strengthened their sway.[16] The distinctive 'caste' identity of Bhumihar Brahman emerged largely through military service, and then confirmed by the forms of continuous 'social spending' which defined a man and his kin as superior and lordly.

In 19th century, many of the Bhumihar Brahmins were zamindars.

Of the 67000 Hindus in the Bengal Army in 1842, 28000 were identified as Rajputs and 25000 as Brahmins, a category that included Bhumihar Brahmins.[19] The Brahmin presence in the Bengal Army was reduced in the late nineteenth century because of their perceived primary role as mutineers in the Mutiny of 1857[20], led by Mangal Pandey. The Kingdom of Kashi belonged to Bhumihar Brahmins and big zamindari like Bettiah and Tekari belonged to them.

In Gujarat,the Brahmin are classified in mainly Nagar Brahmin, Unewal Brahmin, Khedaval Brahmin, Aavdhich Brahmin and Shrimali Brahmin.

In Haryana, the Brahmin are classified in mainly Dadhich_Brahmin, Gaud Brahmin, Khandelwal Brahmin. But large proportion of Brahmin in Haryana are Gaud (about 90%). Approximately all Brahmin in west U P are adi gaur.

In Madhya Pradesh, the Brahmins are classified in mainly Shri Gaud, Sanadhya brahmin, Gujar-Gaud Brahmins. Majority of Shri Gaud Brahmins are found in the Malwa region (Indore, Ujjain, Dewas). Eastern MP has dense population of Sarayuparain Brahmins. Hoshangabad and Harda Distt. of MP have a considerable population of Jujhotia (a clan of Bhumihar Brahmins, e.g. Swami Sahajanand Saraswati) and Naremdev Brahmins.

In Nepal, the hill or Khas Brahmins are classified in mainly Upadhaya Brahmin, Jaisi Brahmin and Kumain Brahmins. Upadhaya Brahmins are supposed to have settled in Nepal long before the other two groups. Majority of hill Brahmins are supposed to be of Khasa origin.

In Punjab, they are classified as Saraswat Brahmins.

In Karnataka, Brahmins are mainly classified into Havyaka speaking Havigannada, Hoysala Karnataka speaking kannada, Shivalli and Kota speaking Tulu, Karahada speaking Marathi and have their own tradition and culture.

In Rajasthan, the Brahmins are classified in mainly Dadhich_Brahmin, Gaur Brahmin,Sanadhya brahmins, Rajpurohit / Purohit Brahmins, Sri Gaur Brahmin, Khandelwal Brahmin, Gujar-Gaur Brahmins. Rajpurohit / Purohit Brahmins are mainly found in Marwar & Godwad region of Rajasthan.Shakdwipiya Brahmins are also found at many places in rajasthan they are the major pujari in many temples of western rajasthan. In Sindh, the saraswat Brahmins from Nasarpur of Sindh province are called Nasarpuri Sindh Saraswat Brahmin. During the India and Pakistan partition migrated to India from sindh province.

In Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh, the Bhardwaj, the Dogra from Himalayan region of Indian subcontinent.

In Uttar Pradesh from west to east: Sanadhya, Gauda & Tyagi (western UP), Kanyakubja (Central UP), Sarayuparin (Central Uttar Pradesh, Eastern, NE,& SE UP) and Maithil (Varanasi), the South western UP, i.e. Bundelkhand has thick population of Jujhotia brahmins (branch of Kanyakubja brahmins: ref. Between History & Legend:Power & Status in Bundelkhand by Ravindra K Jain). On the Jijhoutia clan of Bhumihar Brahmins, William Crooke writes, "A branch of the Kanaujia Brahmins (Kanyakubja Brahmins) who take their name from the country of Jajakshuku, which is mentioned in the Madanpur inscription."[21] Mathure or mathuria Brahmins 'choubeys' are limited to Mathura area.

In West Bengal the Brahmins are classified in Barendra & Rarhi corresponding to the ancient Barendrabhumi (North Bengal) and Rarhdesh (South Bengal) making present day Bangladesh & West Bengal. It is also said that Barendras are traditional Brahmins who practiced the art of medicinal science and surgery rather than the traditional function of being the teacher or the priest, and so many a times they are not considered true brahmins by the Rarhis, although they are their own offshoots.

The traditional accounts of the origin of Bengali Brahmins are given in texts termed Kulagranthas (e.g., Kuladīpīkā), composed around the 17th century. They mention a ruler named Ādiśūra who invited five Brahmins from Kanyakubja [7], so that he could conduct a yajña, because he could not find Vedic experts locally. Traditional texts mention that Ādiśūra was ancestor of Ballāl Sena from maternal side and five Brahmins had been invited in AD 1077. Historians have located a ruler named Ādiśūra ruling in north Bihar, but not in Bengal. But Ballāl Sena and his predecessors ruled over both Bengal and Mithila (i.e., North Bihar). It is unlikely that the Brahmins from Kānyakubja may have been invited to Mithila for performing a yajña, because Mithila was a strong base of Brahmins since Vedic age. Another account mentions a king Shyamal Varma who invited five Brahmins from Kānyakubja who became the progenitors of the Vaidika Brahmins. A third account refers to five Brahmins being the ancestors of Vārendra Brahmins as well. From similarity of titles (e.g., upādhyāya), the first account is most probable.

Besides these two major communities there are also Utkal Brahmins, having migrated from present Orissa and Vaidik Brahmins, having migrated from Western and Northern India.

Pancha Dravida Brahmins

Panch Dravida (the five classes of Southern India): 1) Andhra, 2) Dravida (Tamil and Kerala), 3) Karnataka, 4) Maharashtra and Konkon, and 5) Gujarat. They originate from north of the (now-extinct) Saraswati River.[15]

In Andhra Pradesh, Brahmins are broadly classified into 2 groups: Vaidika (meaning educated in vedas and performing religious vocations) and Niyogi (performing only secular vocation). They are further divided into several sub-castes. However, majority of the Brahmins, both Vaidika and Niyogi, perform only secular professions.[22]

In Karnataka, Brahmins are broadly classified into 2 groups: Madhwa (followers of Shri Madhwacharya) and Smartha (followers of Shri Adi Sankaracharya). They are further divided into several sub-castes. The Tamil Brahmins (both Iyers and Iyengars) are also part of Karnataka Brahmin Community for ages. Other than these groups, there are other brahmin communities viz, Havyaka, Kota, Shivalli, Saraswata etc.

In Kerala, Brahmins are classified into three groups: Namboothiris, Pottis and Pushpakas. (Pushpakas are commonly clubbed with Ampalavasi community). The major priestly activities are performed by Namboothiris while the other temple related activities known as Kazhakam are performed by Pushpaka Brahmins and other Ampalavasis. Sri Adi Shankara was born in Kalady, a village in Kerala, to a Namboothiri Brahmin couple, Shivaguru and Aryamba, and lived for thirty-two years. The Namboothiri Brahmins, Potti Brahmins and Pushpaka Brahmins in Kerala follow the Philosophies of Sri Adi Sankaracharya. The Brahmins who migrated to Kerala from Tamil Nadu are known as Pattar in Kerala. They possess almost same status of Potti Brahmins in Kerala.

In Tamil Nadu, Brahmins belong to 2 major groups: Iyer and Iyengar. Iyers comprise of Smartha and Saivite Brahmins and are broadly classified into Vadama, Vathima, Brhatcharnam, Ashtasahasram, Sholiyar and Gurukkal. There are mostly followers of Adi Shankaracharya and form about three-fourths of Tamil Nadu's Brahmin population. Iyengars comprise of Vaishnavite Brahmins and are divided into two sects: Vadakalai and Thenkalai. They are mostly followers of Ramanuja and make up the remaining one-fourth of the Tamil Brahmin population.

In Maharashtra, Brahmins are classified into five groups: Chitpavan Konkanastha Brahmins, Gaud Saraswat Brahmin, Deshastha Brahmin, Karhade Brahmin, and Devrukhe. As the name indicates, Kokanastha Brahmin are from Konkan area. Gaud Saraswat Brahmins are from Konkan region or they may come from Goa or Karnataka, Deshastha Brahmin are from plains of Maharashtra, Karhade Brahmins are perhaps from Karhatak (an ancient region in India that included present day south Maharashtra and northern Karnataka) and Devrukhe Brahmins are from Devrukh near Ratnagiri.

In Madhya Pradesh the descendents of Somnath temple priests, Naramdev Brahmin, Who migrated from Gujrat to Madhyapradesh after the Mohd. Ghazni notorious forays in Saurashtra and desecration of Somnath, and sedenterized along the coast of Narmada river hence derived their name i.e. Narmdiya brahmin or Naramdevs. Guru of Adi guru Shankaracharya, shri Govindacharya claimed to belongs to this community who initiated him in the Omkareshwar in the bank of river Narmada. Naramdevs are in high concentration in Nimar (Khandwa and Khargone)and Bhuvana region (Harda) of Madhya Pradesh.

In Gujarat, Brahmins are classified into eight groups: Anavil Brahmin, Audichya Brahmins, Bardai Brahmins, Girinarayan Brahmins, Khedaval, Nagar Brahmins, Shrimali Brahmins, Sidhra-Rudhra Brahmins and Modh Brahmins. The Modh Brahmins worship Matangi Modheshwari mata (Modhera) and are mostly found in North Gujarat and in the Baroda region.

Gotr and pravar

In general, gotra denotes any person who traces descent in an unbroken male line from a common male ancestor. Panini defines gotra for grammatical purposes as ' apatyam pautraprabhrti gotram' (IV. 1. 162), which means 'the word gotra denotes the progeny (of a sage) beginning with the son's son. When a person says ' I am Kashypasa-gotra' he means that he traces his descent from the ancient sage Kashyapa by unbroken male descent. According to the Baudhâyanas'rauta-sûtra Viśvāmitra, Jamadagni, Bharadvâja, Gautama, Atri, Vasishtha, Kashyapa and Agastya are 8 sages; the progeny of these eight sages is declared to be gotras. This enumeration of eight primary gotras seems to have been known to Pānini. These gotras are not directly connected to Prajapathy or latter brama. The offspring (apatya) of these eight are gotras and others than these are called ' gotrâvayava '.[23]

The gotras are arranged in groups, e. g. there are according to the Âsvalâyana-srautasûtra four subdivisions of the Vasishtha gana, viz. Upamanyu, Parāshara, Kundina and Vasishtha (other than the first three). Each of these four again has numerous sub-sections, each being called gotra. So the arrangement is first into ganas, then into pakshas, then into individual gotras. The first has survived in the Bhrigu and Āngirasa gana. According to Baudh., the principal eight gotras were divided into pakshas. The pravara of Upamanyu is Vasishtha, Bharadvasu, Indrapramada; the pravara of the Parâshara gotra is Vasishtha, Shâktya, Pârâsharya; the pravara of the Kundina gotra is Vasishtha, Maitrâvaruna, Kaundinya and the pravara of Vasishthas other than these three is simply Vasishtha. It is therefore that some define pravara as the group of sages that distinguishes the founder (lit. the starter) of one gotra from another.

There are two kinds of pravaras, 1) sishya-prasishya-rishi-parampara, and 2) putrparampara. Gotrapravaras can be ekarsheya, dwarsheya, triarsheya, pancharsheya, saptarsheya, and up to 19 rishis. Kashyapasa gotra has at least two distinct pravaras in Andhra Pradesh: one with three sages (triarsheya pravara) and the other with seven sages (saptarsheya pravara). This pravara may be either sishya-prasishya-rishi-parampara or putraparampara. When it is sishya-prasishya-rishi-parampara marriage is not acceptable if half or more than half of the rishis are same in both bride and bridegroom gotras. If it is putraparampara, marriage is totally unacceptable even if one rishi matches.

Sects and rishis

Due to the diversity in religious and cultural traditions and practices, and the Vedic schools which they belong to, Brahmins are further divided into various subcastes. During the sutra period, roughly between 1000 BCE to 200 BCE, Brahmins became divided into various Shakhas (branches), based on the adoption of different Vedas and different rescension Vedas. Sects for different denominations of the same branch of the Vedas were formed, under the leadership of distinguished teachers among Brahmins.

There are several Brahmin law givers such as Angirasa, Apasthambha, Atri, Brihaspati, Boudhayana, Daksha, Gautam, Harita, Katyayana, Likhita, Manu,[25] Parasara, Samvarta, Shankha, Shatatapa, Ushanasa, Vashishta, Vishnu, Vyasa, Yajnavalkya and Yama. These twenty-one rishis were the propounders of Smritis. The oldest among these smritis are Apastamba, Baudhayana, Gautama, and Vasishta Sutras.

Descendants from Brahmins

Many Indians and non-Indians claim descent from the Vedic Rishis of both Brahmin and non-Brahmin descent. For example the Dash and Nagas are said to be the descendants of Kashyapa Muni. Visvakarmas are the descendants of Pancha Rishis or Brahmarshies. According to Yajurveda and brahmanda purana They are Sanagha, Sanathana, Abhuvanasa, Prajnasa, Suparnasa. The Kani tribe of South India claim to descend from Agastya Muni.

The Gondhali, Kanet, Bhot, Lohar, Dagi, and Hessis claim to be from Renuka Devi.

The Kasi Kapadi Sudras claim to originate from the Brahmin Sukradeva. Their duty was to transfer water to the sacred city of Kashi.[27]

Dadheech Brahmins/dayama brahmin trace their roots from Dadhichi Rishi. Many Jats clans claim to descend from Dadhichi Rishi while the Dudi Jats claim to be in the linear of Duda Rishi.

Lord Buddha of course, was a descendant of Angirasa through Gautama. There too were Kshatiryas of other clans to whom members descend from Angirasa, to fulfill a childless king's wish.[28]

The backward-caste Matangs claim to descend from Matang Muni, who became a Brahmin by his karma.

The nomadic tribe of Kerala, the Kakkarissi according to one legend are derived from the mouth of Garuda, the vehicle of Vishnu, and came out Brahmin.[29]

Brahmins taking up other duties

Brahmins have taken on many professions - from being priests, ascetics and scholars to warriors and business people, as is attested for example in Kalhana's Rajatarangini. Brahmins with the qualities of Kshatriyas are known as 'Brahmakshatriyas'. An example is the avatara Parshurama who destroyed the entire Haiheyas 21 times. Not only did Sage Parashurama have warrior skills but he was so powerful that he could even fight without the use of any weapons and trained others to fight without weapons. The Bhumihar Brahmins were established when Parashurama destroyed the Kshatriya race, and he set up in their place the descendants of Brahmins, who, after a time, having mostly abandoned their priestly functions (although some still perform), took to land-owning.[30]

Today there is a caste, Brahmakhatris, who are a clan of the Khatris, however this is suspicious since Khatris are a business caste/community of Punjab and belong to the Vaishya caste. Khatri has often been misinterpreted as a variation of the word Kshatriya, meaning warrior, however there are no records of any Khatri kingdoms or empires in Indian history and this claim to Kshatriya is recently made in the 20th century.

Perhaps the word Brahma-kshatriya refers to a person belonging to the heritage of both castes. However, among the Royal Rajput households, brahmins who became the personal teachers and protectors of the Royal princes rose to the status of Rajpurohit and taught the princes everything including martial arts. They would also become the keepers of the Royal lineage and its history. They would also be the protectors of the throne in case the regent was orphaned and a minor.

Kshatriyan Brahmin is a term associated with people of both caste's components.

The Pallavas were an example of Brahmakshatriyas as that is what they called themselves. King Lalitaditya Muktapida of Kashmir ruled all of India and even Central Asia.

King Rudravarma of Champa (Vietnam) of 657 A.D. was the son of a Brahmin father..

King Jayavarma I of Kambuja (Kampuchea) of 781 A.D. was a Brahma-kshatriya.

Brahmins with the qualities of a Vaisya or merchant are known as 'Brahmvyasya'. An example of such persons are people of the Ambastha caste, which exist in places like South India and Bengal. They perform medical work - they have from ancient times practiced the Ayurveda and have been Vaidyas (or doctors).

Many Pallis of South India claim to be Brahmins (while others claim to be Agnikula Kshatriyas.) Kulaman Pallis are nicknamed by outsiders as Kulaman Brahmans. Hemu from Rewari, Haryana was also a Brahmin by birth.

See also

Agni-brahman <>

Bara-Brahman <>

Brahman: 'Central Provinces' <>

Brahman: Kanaujia, Kanyakubja <>

Brahman: Maharashtra, Maratha <>

Brahman: Sanadhya, Sanaurhia <>

Brahman-Kanada,Brahman-Karnatic: Deccan <>